Witch hunt in the Duchy of Westphalia

The witch hunt in the Duchy of Westphalia , which belongs to Kurköln, took place in several waves between the late 16th century and 1728. The region was one of the focal points of persecution in the Holy Roman Empire and thus in Europe in the 17th century . The first wave of persecution occurred between 1590 and 1600. The trials and executions reached their peak around 1630, as in the empire as a whole. Another, much weaker wave of lawsuits occurred in the 1640s and 50s. After that, the persecution gradually subsided. After 1691 only a few trials took place. The last execution took place in Winterberg in 1728 .

The causes were varied. On the basis of a widespread belief in witches, epidemics, fires, famines or similar afflictions often encouraged the persecution of alleged witches and wizards who were held responsible for the hardships. Other regions may also have played a role as role models. The role of the authorities in the form of the sovereign, the elector and archbishop of Cologne, and his representative, the Landdrosten , was ambivalent. On the one hand, they tried to regulate the demands of parts of the population for action against the alleged witches, for example through the witchcraft process code of 1607, without any doubts about the possibility of witchcraft itself being connected with it. On the other hand, especially at the height of the persecution, they were among those who advocated tough action against the witches. This is another reason why the number of trials and executions could increase massively. The witch commissioners appointed by the government therefore also became protagonists of the persecution.

Some critics also spoke out publicly against the “witchcraft madness”. In the second half of the 17th century, the authorities, who had in the meantime arose a certain skepticism about the procedure, gradually began to regulate the procedures more and this time more effectively.

Causes of persecution

As in other regions, several factors acted together to trigger the persecution. The belief in witches and wizards was reinforced by the general moments of crisis of the 16th and 17th centuries (epidemics, turmoil of war, social change, hunger crises as a result of the Little Ice Age , etc.). These were perceived by the population as an existential threat to life, property and salvation . In some cases, research even found a profound break in the history of mentality in the last decades of the 16th century. There was a turn away from a rather hopeful, this-worldly Renaissance mentality and a turn to a dogmatically narrowed, religious and other- worldly oriented worldview. The belief in witches was spread through numerous pamphlets and tracts , but also through sermons in the churches. It is likely that the Hexenhammer was received in the duchy shortly after it was first published. Parts of the population put pressure on the urban or sovereign ranks to take more vigorous action against the "witchcraft". In addition, there was the willingness of the authorities to give in or even to control the persecutions. The pursuit of social, economic or political advantages at the various levels is also not to be overlooked.

The alleged crimes corresponded to the accusations customary in Central Europe. The witches or sorcerers are said to have entered into a covenant with the devil . This is said to have taken place through a sexual union - the devil's compensation. For the surrender of souls, the witches are said to have received magical powers with which they could harm their fellow men . The witches are said to have often met with each other and with the devil on a witch's sabbath. There was also the assumption that the witches could transform themselves into animals. In a lengthy communication process, regional characteristics emerged, for example with regard to the concept of the Devil's Pact, while in the individual areas, such as in Westphalia, a certain degree of standardization was achieved.

Beginnings of the persecution

The General Chapter of the kangaroo court has at its meeting in Arnsberg 1490 Witchcraft first defined in the Duchy of Westphalia as a criminal offense: "If any man heresies cooking up and puts forward; if anyone apostates and becomes a pagan ; someone like that witches and conjures up or establishes an alliance with the evil one. ” With the decline of the feme jurisdiction in the 16th century, it lost its importance for the witch hunts and trials. Their function was essentially taken over by the Gogerichte and the noble patrimonial courts .

One of the first cases in the region took place in Werl in 1508 . A case from 1523 in Brilon is better known . At that time, on the intervention of Elector Friedrich IV von Wied , the defendant was released against the will of the local authorities. At least in this early phase, such interventions in favor of the defendant were not uncommon. This was not based on a fundamental rejection of the witch persecution, but the authorities insisted on a lawful process, including the right to defense. A woman in Rüthen was also released in 1573 for a similar reason.

Despite this relative reluctance by the electoral authorities, the first major trials took place in the region in the last third of the 16th century. The small town of Kallenhardt was a focus of this wave of persecution. In the years 1573/74 nine "witches" were burned there. The number in the following year is not known, but in 1575/76 there were again six victims. Four people were executed in nearby Rüthen in 1578/79. At the same time there were also the first persecutions in the south of the region in Drolshagen and in the Bilstein office .

Process wave 1590–1600

A large part of the southern Sauerland was controlled by Kaspar von Fürstenberg . His attitude was therefore of great importance to the extent of the persecution in this part of the region. Until 1590 he tried to prevent arbitrary persecution in the interests of correct litigation. The residents of Drolshagen then complained to the Elector Salentin von Isenburg that the Drost did not act energetically enough against the witchcraft, although several people had already been executed with Fürstenberg's approval. After 1590, however, persecution also increased sharply in the southern Sauerland.

Kaspar von Fürstenberg played a central role in the escalation. An important reason for his change of heart was that he blamed the death of his wife on the actions of an alleged witch by the name of Dorothea Becker , wife of a judge and therefore called "the judge's". In addition to the change in attitudes at von Fürstenberg, other factors also played a role. It can be assumed that the new sovereign Ernst von Bayern promoted the witch hunts. In addition, a series of poor harvests had increased belief in witches.

In the Bilstein rule alone , 28 people were accused of witchcraft in 1590 and at least 21 of them were executed. In 1592 another 19 people died there. There were also persecutions in Olpe , Drolshagen, Attendorn , Oberkirchen and the Fredeburg office . Litigation also broke out around this time outside of Kaspar von Fürstenberg's sphere of influence. Among them were again Kallenhardt and Rüthen, but also Padberg , Hallenberg , Brilon, Balve , Belecke , Hirschberg , Bödefeld and Menden .

Legal appeals against witchcraft allegations

The case of the "Richterschen" mentioned above is of interest as it shows that at least at this time it was still possible to take legal action against the suspicion of witchcraft and to restore one's own threatened honor: Dorothea Becker was already under in the 1570s Suspected witchcraft and had secured the help of a lawyer. This relied on the process of so-called canonical purgation (Latin: purgare "clean"). Although originally intended for clerical conflicts, in certain cases the procedure could also be used on persons accused of witchcraft without any specific evidence. Dorothea Becker swore her innocence in 1575 with the help of oath assistants . Thereupon the court in Attendorn issued a Documentum Purgationis to her . After that, there were initially no more suspicions for a long time. Only in 1587 and 1590 was she denounced by suspects of witchcraft that she had caused the death of Kaspar von Fürstenberg's wife through magic spells . She tried in vain to take legal action again, but could not avoid being tortured several times. However, she did not confess, so the trial against her dragged on for years and she was eventually expelled from the country for lack of evidence.

Even people without a legal background could still hope to avert suspicion of witchcraft with the help of lawsuits. This was the case, for example, in the case of Hoberg and Vollmer against Diedrich von Esleve. Here, too, personal blows of fate played a role in the suspicion of witchcraft. Esleve had a sick daughter who he believed had been bewitched. He even had her expelled from the devil without this having led to recovery. He now suspected the farmer Christian Hobrecht and the farmer Magdalena Vollmer of being in league with the spirit that had come to his daughter. There were various, sometimes violent, disputes between the two sides. Esleve then officially sued Hobrecht and Vollmer with the authorities. In 1605, those accused of witchcraft filed a lawsuit through a lawyer at the electoral court in Arnsberg, demanding a revocation and a fine from Esleve. As a result, witnesses were heard, and Esleve's side provided further information that was part of the pattern of witchcraft accusations typical of the time. Most of the witnesses, however, exonerated Hobrecht and Vollmer, and after an extremely lengthy process, Esleve was sentenced in 1607 to withdraw the accusations and to pay fines of forty and fifty Reichstalern respectively . Von Esleve then moved to the official office in Cologne and von Werl . This long-standing procedure was also unsuccessful. After all, the Reich Chamber of Commerce was also involved, without a judgment being passed down.

Electoral witch trial ordinances

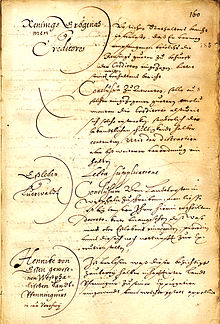

This first wave of persecution ended around 1600. The reasons remain unclear; intervention by the sovereign authorities probably played a role here. In 1607, Ferdinand von Bayern issued a witch trial code for the entire sphere of influence of the Elector of Cologne . This assumed that “after the horrible and horrific mischief of magic, unfortunately in these careful and dangerous times, it takes a mean transition. (...) to punish such misdeeds to the best of his ability ” . But order also wanted to regulate the processes. "Nevertheless, you have to be careful that in this dangerous situation there is sobriety and ruin, also honor and good, great discretion is needed." This also served that the simple judges in "doubtful and overwhelming their minds." Pfhaellen, always impartial legal counsel or the Higher Regional Court (...) and should not undertake or recognize anything for themselves. ” As a legal basis, the Witch Trial Code referred to Article 44 of the Constitutio Criminalis Carolina , issued by Charles V in 1532.

A so-called accumulation process was planned. After an arrest, the plaintiff was required to provide bail and a surety . If he was not able to do so, the plaintiff himself would have had to go to prison until the end of the trial. In the event of a possible acquittal, he owed the defendant compensation. A lawsuit would have been fraught with enormous risk. Had this provision been applied, there would hardly have been any charges. In addition, ex officio processes like the Inquisition were also possible. The great persecutions of the following decades then took place on this basis. "If no clergyman is supposed to bring about this, but rather to the authorities this devilishly divine magical work vel publica fama through common shouting or denunciando about hideous persons, then it will be incumbent on the same Amptswegen to obtain necessary information about it ex officio."

The defamation by two neutral witnesses was necessary for a trial to begin . In addition, the denunciation by convicted witches or wizards played an important role. If they revealed names of people who were also allegedly in league with the devil under torture , there were also trials. This contributed greatly to the escalation of the persecution. Torture was intended for the denunciation. Overall, torture was also used on minor suspicions or indications. If a victim had been under threat or in the process of being tortured, they had to be interviewed again the next day without torture. If she withdrew her confession, she could be tortured again. If a suspect had confessed and withdrawn three times, the case had to be brought to the elector. This had to either acquit the suspect or expel the country. Overall, the official regulation of the procedure has reduced rather than increased the possibilities of acquittals.

In 1628 the Witch Trial Code was confirmed and, above all, the regulation of financial issues related to the witch trials was added. Although the court costs were generally to be borne by the convicts, the entire estate was not confiscated and the possibility of enrichment by judges and other persons was limited. Apparently the witches' court order was not always observed.

The procedural rules in the Duchy of Westphalia were linked to the appointment of two lawyers as general commissarians inquistitionis magiae . These should oversee the proceedings of the lower courts and guarantee a professional process. However, the commissioners had their own material interest in as many trials and judgments as possible. They were entitled to one Reichstaler per arrest and torture warrant and twice that amount in the case of a judgment. The days on which the torture took place was additionally compensated. One problem with the procedural rules was that those involved often did not adhere to them. The pastor Michael Stappert accused the witch commissioner Heinrich von Schultheiss of forbidden to ask the defendants suggestive questions. Stappert blamed the authorities in particular for the growing number of trials.

Forced Confessions

Pastor Michael Stappert reported from his pastoral practice how confessions were obtained. It depicts the case of Agatha Kricks from Hirschberg, who was accused of witchcraft in 1616 and then "miserably tortured and tortured" . Stappert visited her as a pastor in prison. The defendant protested her innocence and stated that she had been forced to make the confession. “During the torture I had to say that I could do magic. But the righteous God in heaven knows about my innocence and that I had to lie to myself, and if I were a sorceress, I wanted to confess it like the others and confess this to you as my confessor. ” Stappert was obviously closed by her innocence Not yet convinced at the time, but admonished her not to allow herself to be further seduced by the devil and to confess her guilt to God and the judges. The defendant continued to hold onto her innocence. "Oh God, oh God, if I were guilty, wanted and I should do it, but because I am not guilty, should I then nevertheless lie against my confessor and say I'm guilty, while I'm innocent?" Next she said: “Mr. Pastor, you have admonished me enough, I want to excuse the Lord before God on the last day. And if I was guilty and refused to confess it to my confessor when I was dying, what consolation should that be for my bliss? I must die as a sorceress in front of everyone, and in such a case I would be worthy of eternal damnation. Now God knows that I am not guilty, and I want to live and die on it. "

Heinrich von Schultheiss made recommendations on how the torture should take place. He described exactly how the leg screws should be used and how the witch commissioner and executive executioner should work together. “For the eighth / the Commissarius, with his admonition and auisation, have the leg screws screwed on the prisoner / and because, apart from long experience, / that a lot and not a little help / that the executioner at the Commissary's sign either screwed on or released - so the Commissarius might give a sign to the executioner mouendo baculum vel annuendo vel monstrando / then he should behave at any time / the executioner must diligently pay attention to such. (...) For the ninth / When the executioner knows how to use the torture on the Commissarij's sign / so the Commissarius can put the leg screws on / Truly and diligently Ha also implicitly admonish the witch's name of his teacher / and the commissarius notes that / that the magic mouirt and meekly through the serious memory / so the commissarius sub ipisi verbis adhortaorijs give the executioner a sign / that he screw up. To the ten / so the commissarius prevented the tormentor from pressing the screws with hasty kit or speed / but slowly / the slower / the better. ” Should the leg screws not lead to success, the witches should be raised and with rods sprinkled with holy water beforehand should be scourged, the body should be rubbed with holy water and salt. (...)

Riots in Geseke

A problem with the authorities' regulation became apparent during a wave of lawsuits in Geseke in 1618 . Here the judges and councilors tried to carry out the procedure according to the order of 1607. They did not have enough evidence and lacked two witnesses to initiate due process. This led to downright riots among the population. She accused the authorities of wanting to cover up the accused, some of whom were upper class, and demanded torture and, ultimately, execution. The crowd threatened violence against possible lawyers for the defendant. Ultimately, the judges and lay judges bowed to the pressure of the street, and appropriate processes were initiated. Only when one of the defendants intervened, at the instigation of an influential family, the witch commissioners could the proceedings according to the order of 1607 take place. At least some of the defendants who did not confess were acquitted. Others under the torture were executed. What is remarkable about the events in Geseke is the fanaticism of the population. The search for scapegoats played a role, as did incitement by a clergyman and the mistrust of the common people against the wealthy classes.

The height of the persecution around 1630

Extent of persecution

As in other territories, the persecution of witches in the Duchy of Westphalia reached its peak around 1630. The intensity of the persecution was as high as in the Würzburg monastery in Franconia. Around 900 people were executed there between 1623 and 1631 (on the events in the city of Würzburg: witch trials in Würzburg ). In the Duchy of Westphalia there were 600 proven charges between 1628 and 1631. Most of these ended with execution. In addition, there is an unknown number of unsold cases. One of the centers was the Balve Office . There, 280 people were burned at the stake between 1628 and 1630 alone. In Menden, Bilstein, Oberkirchen, Werl and in the Fredeburg office the numbers were between about 45 and 80 cases. In Rüthen there were only about 20 cases. The reason was that the trials stalled because of disputes between the magistrate and the witch commissioner. There were other verifiable cases in Hallenberg, Hirschberg, Olpe, and in the Alme patrimonial court , each with around 20 cases. How many cases there were in Allendorf , Erwitte , Remblinghausen , Brilon, Marsberg , Winterberg and elsewhere cannot be precisely determined on the basis of the sources. At the end of 1630 the wave of persecution subsided sharply.

Witch trials in Oberkirchen

The development of the witch trials in the Oberkirchen patrimonial court of the Barons von Fürstenberg has been well researched . The trigger for the wave of persecution of 1630 was the interrogation of nine-year-old Christine Teipel , who had claimed that she was a witch. The background for their information may have been an attempted child abuse in their past and leading questions from the interrogator. In her testimony it said about the devil's pact of a resident: “Confessingly, that Johan Bell ... before long, doesn't know how much jar, she learned the magic in Stephans bakehouse, ... (She) also agreed to the devil, the devil was called in a brave young figure,… come to ir,… said to ir whether she wanted to stand [by him]. In the druff she replied: yes, if he wanted to do something good, he promised to do it. " The witches 'dance on the witches' Sabbath and the devil's compensation brought the interviewees into play: " His boel (devil's humiliation) hett danced with ir ... The dance hette woll was two hours. ” (…) “ Confessed that the bol (devil's bull) had a body so that you in ir shamb etc., had no pleasure in it, when we had wood; and as often as she was drawn to the dance, he would have come to her first and boliret [= have sexual intercourse], and if they didn't want to suffer, he would have dared to hit you ”[= threatened] . These and other confessions were followed within a few weeks by the conviction of 67 people, including Christine Teipel. This corresponded to 10% of the population of the place.

Reasons for the process wave

One of the reasons the persecution escalated was the poor economic situation. The years before were marked by poor harvests, high food prices and widespread hunger. As a result, the general mortality increased sharply. However, the hunger crisis does not fully explain the development. In comparable constellations around 1635/36 there was no significant increase in the number of processes.

A driving force was the authorities. This applies both to Elector Ferdinand of Bavaria and to his deputy in the duchy, Landdrosten Friedrich von Fürstenberg . One thesis explains the change with the general political situation in the Thirty Years War . The Catholic and Counter-Reformation forces were at the height of their success at this time and had strongly pushed Protestantism back. It was therefore possible at this time to take action against the witches as a supposed further opponent. There are indications that witchcraft was seen as related to Protestantism. So the large number of witches in Balve was explained by the proximity of the evangelical county of Mark . However, there is no tangible evidence for the motives of the authorities.

One factor was that the witch persecution in other regions, especially the great wave of persecution in the Würzburg monastery, was taken as a model. A statement by the Mayor of Arnsberg, Henneke von Essen , handed down to Heinrich von Schultheiß , proves that the events in southern Germany were known . Von Essen justified his objection to intentions to be persecuted in Arnsberg with the fact that he feared a “Wirzbürgisch work”, that is, persecution out of the control of the local authorities. Indeed, an important impetus also came from the people of the country. Citizens of the city of Hallenberg turned directly to the sovereign, bypassing the local magistrate, and successfully asked for a witch commissioner to be sent. In contrast to the past, the authorities were now ready to give in to the urge for persecution. There was probably a top-down approach. An electoral decree is known from Balve, according to which the inhabitants should prepare prisons and pyre. Shortly afterwards, an electoral witch commissioner arrived and the first trials were opened. Other official orders also speak in favor of a controlled approach. At a meeting of the court council in Bonn there was talk of the need to eradicate witchcraft. The fact that, as Gerhard Schormann has asserted, Ferdinand pursued a war against witches with a centrally controlled extermination program from the beginning of his rule has meanwhile been put into perspective. This is unlikely as persecution only began to increase decades after he took office. Rather, the decisive impetus came from the population.

Protagonists and opponents of the persecution

The witch commissioners were the driving forces behind the persecution. The number of processes they initiated varied. Kaspar Reinhard was responsible for several hundred cases, particularly in the Balve area. But he was also active in Attendorn, Olpe, Drolshagen, Wenden and Allendorf. Reinhard was known beyond the borders of the country as a particularly fanatical witch hunter. Numerous complaints were made against him and there was even an assassination attempt on Reinhard.

The sources on the witch commissioner Heinrich von Schultheiss are particularly good. He studied in Cologne and had a doctorate in law. In 1610 he entered the electoral service and initially worked at the court court in Cologne before moving to Arnsberg in 1614 as electoral councilor and advocatus fisci (i.e. representative of the treasury in litigation with subjects). As a witch commissioner he worked in Hirschberg in 1616, in Arnsberg in 1621, in Erwitte in 1628 and in Werl in 1643. Around 1630 he was involved in the trial against Henneke von Essen. In gratitude for services rendered, he was raised to the nobility. At times he had to flee from the advancing Protestant troops to Cologne, where in 1634 he published a book with the title "Detailed Instruction How to proceed in Inquisition matters of the growing vice of magic ..." . It was not so much a scientific and legal work in the narrower sense, but a writing that was primarily aimed at the nobility in their capacity as holders of patrimonial jurisdiction.

The book aroused opposition from contemporaries early on, and even the University of Cologne rejected it, but the book is a good source for the thinking of proponents of the witch hunt.

In addition to the supporters of the persecution, there were also opponents among contemporaries such as B. Anton Praetorius . Criticism also increased, especially in the wake of the great wave of persecution around 1630. Some of them were not critics from the start. Henneke von Essen, for example, used to be involved in witch trials as a judge himself and was even present at torture before he publicly expressed criticism. He was arrested, charged with witchcraft, tortured and died in prison. The pastor Michael Stapirius also preached against witches in the beginning and incited the population. When, as the pastor of those sentenced to death, he noticed that the most nonsensical confessions had been made under torture, he became an opponent of the witch trials. In contrast, in 1628/30 he wrote a treatise that was initially not intended for publication, which was only printed in 1676 by Hermann Löher in his book Hochnötige Unterthanige Wemütige Klage Der Pious Invalid in Amsterdam. A number of other clergymen were also critical.

Persecutions after 1630

The great wave of persecution ended after 1630 for various reasons. A further continuation threatened the depopulation of entire areas, so that a certain rethinking began among the authorities. At the imperial level there were certain signals that the time of unrestrained persecution was nearing its end. A certain Cramer von Attendorn, who got caught up in the mill of witch hunts, had obtained a judgment from the Reich Chamber of Commerce, which called for more correct litigation in the Kurkölner dominion area. In addition, the successes of the Protestant troops interrupted the trials.

It was not until 1637 that there was another trial in Alme. Others followed between 1641 and 1644 in Werl, Oberkirchen, Brilon, Olpe and Drolshagen. In 1641, the self-accusations and testimony of five school children sparked a wave of persecution in the county area . There were again connections with rising grain prices. Again the population asked the authorities to intensify the witch hunts. So residents of Oberkirchen turned to Friedrich von Fürstenberg several times. A similar pattern of inflation and persecution was evident between 1652 and 1654 in the Balve district, in the Gogericht Rüthen and in the area of Olpe. At least 45 people were executed. The fact that the intensity of the persecution did not reach the level of 1630 had something to do with the skepticism of Friedrich von Fürstenberg in the southern Sauerland region , who had succeeded his father, who was open to the witch trials, as court lord. There were no trials in his own territory until his death in 1662. The residents of Bilstein therefore complained that no example had been set for 40 years. The new elector Maximilian Heinrich von Bayern also tried to prevent new excesses and advised the authorities in Winterberg and Hallenberg, for example, to carefully examine suspicious factors, to report them and to await further instructions. Further instructions reinforced this. Thereafter, suspicions should not be immediately imprisoned and tortured, circumstantial evidence should be examined more carefully and the suspects should be given the opportunity to justify themselves. Objectifiable knowledge should take the place of defamation. In the witch trial instruction of 1659, the offense of witchcraft was not questioned in principle, but it insisted on protecting the innocent and also admitted abuses: "Now this vice is so hideous and cruel that the almighty God no greater service than can happen through its extermination, but it is cheap to proceed with such circumspection and therefore cautiously that no one should suffer innocently in honor and body, to the extent that it was often felt before this that during examination and torquing the Accused committed all kinds of abuses. "

As a result, the number of processes decreased significantly. After 1665 there were only 47 trials that ended in the death of the accused. Geseke stands out among them, where there were a total of 19 executions after the fires in 1670 and 1691. These were the last mass trials in the region. Around 1685 there were witch trials against several accused in Brilon. This included a trial against the multiple mayor Johann Koch. This was preceded by an instruction from the Landdrosten to the city to intensify the persecution. Apparently, this was done in the city. As a result, the control of the lower courts was continuously expanded. In 1695/96 the court councilor in Bonn issued instructions to the courts in Olpe and Brilon, according to which from now on no one should be arrested without an expert opinion from an impartial lawyer and no one should be threatened with torture at the first interrogation. The suspect had the right to a copy of the indictment and a defense attorney. If he couldn't afford one, a defense attorney was appointed. Torture could only be ordered if it had been approved by the government in Arnsberg or by the court council.

As before, however, the possibility of witchcraft was assumed. As a result, there were still individual convictions and executions. In 1695, about a twelve-year-old girl was executed in Olpe. The trials in Geseke in 1708 and in Winterberg in 1728 are the last cases in the duchy to end with executions. A final trial in Brilon in 1730 resulted in an acquittal.

Victim

A total of around 1100 procedures can be detected in the region with a quota of at least 80% of those executed. The number of male convicts in the Duchy of Westphalia was comparatively high. In Bilstein, 1629 of a total of 34 killed were 22 men. A year later, half of the 12 defendants were male. The data for the total proportion of men differ in the literature. Decker gives a share of 25% and Rolf Schulte of 37%. Schulte can see a change over time. While the proportion of men was 16% between 1570 and 1589, it was 46% between 1650 and 1699. In any case, these numbers were above average. However, the proportion of men affected was also very high in other Catholic territories, which Schulte tries to explain with a denominational image of a witch and a special description of the crime. Children were affected relatively rarely. However, this also happened, as the cases in Oberkirchen and Grafschaft have shown.

A detailed study of the Oberkirchen court is available on the social background of the defendants. The number of farmers and kötter roughly corresponded to their share in the population. Medium-sized and larger farmers were statistically slightly more represented. Overall, the social status played no discernible role in the trials in the Oberkirchen court. In contrast, family relationships played a role. Most of the defendants in 1630 had family ties to the victims of the first wave of persecution in the Oberkirchen court in 1594/95. The people executed in 1641/42 and 1669/71 had family ties to the suspects of 1630.

Remembrance and rehabilitation

Rüthen was one of the main focuses of the persecution. From 1573 to 1659, 169 witch trials are known from the town and the Gogericht Rüthen. Well-known cases include those against Grete Adrian and Freunnd Happen . At least 79 people were executed in total. The city council of the city of Rüthen decided on March 31, 2011 a socio-ethical posthumous rehabilitation of the local victims of the witch hunts.

The City Council of Sundern discussed an analogous proposal on April 18, 2011. In Arnsberg there are efforts to commemorate Henneke von Essen , for example in the form of a plaque . In Balve, Bad Fredeburg, Geseke, Hirschberg, Menden, Olpe, Rüthen, Holthausen and Winterberg, memorial plaques or monuments commemorate the victims of the persecution of witches. In Fredeburg there is a memorial plaque on the so-called witch's chapel. At this point the condemned are said to have pleaded for consolation and forgiveness for the last time. In 2006, a memorial stele was unveiled on the Galgenberg, the historic place of execution, in Balve. A memorial cross in Hirschberg has been commemorating the victims since 1986. The Wittgenstein – Sauerland forest sculpture trail leads to the former Hexenplatz in Oberkirchen. There is the sculpture Der Hexenplatz by Lilli Fischer. In Menden, the city library was named after Dorte Hilleke , who resisted torture and thus broke the chain of denunciations. There is a permanent exhibition on the subject in the Holthausen Slate Mining and Local History Museum . The so-called Rüthener Hexenturm also houses an exhibition on this topic.

swell

- Michael Stappert : Spectacles treatise. In: Hermann Löher: Hochnötige Unterthanige Wemütige Klage Der Pious Invalid; Wherein all high and vicious superiorities / sampt their subjects clearly / apparently have to see and read / how the poor, ineffectual pious people are attacked by false magical judges by fahm and honor robbery / forced by them through the unchristian banck of torture and torment become / terrible / inhumane murderous and deadly sins to lie to oneself and others more / and to say them unjustly / falsely. Which Messrs. Tannerus / Cautio Criminalis / Michael Stapirius / affirmed harshly. Delicately depicted with different beautiful pieces of copper after life. Everything put together with great diligence and effort / for the consolation and Heyl of the pious Christian-Catholic people: Through Hermannum Loher The city of Amsterdam citizens. Printed at Amsterdam. Before the Auctor / bey Jacob de Jonge. Anno 1676. ( online version )

- Heinrich von Schultheiß: An Detailed Instruction How to proceed in Inquisition matters of the increased vice of magic against the magic of the divine majesty and of Christendom enemies without the risk of the innocent ... , Cologne 1634 ( digitized version )

- Hexen -ordnung of the Elector Ferdinand [from July 24th 1607], together with addendum and estimate from November 27th 1628 , author. in: Johann Suibert Seibertz: Document book on the regional and legal history of the Duchy of Westphalia. Vol. 3 1400-1800 Arnsberg, 1854 No. 1038, pp. 298-306 digitized

literature

- Alfred Bruns (Ed.): Witches. Jurisdiction in the Sauerland region of Cologne. Schmallenberg 1984. Therein u. a .:

- Alfred Bruns: The Oberkirchen witch protocols. Pp. 11-90

- Rainer Decker : The social background of the witch hunt in the Oberkirchen court. Pp. 91-118

- Otto Höffer: The persecution of witches in the Bilstein office, pp. 119-136

- Fritz Schreiber: Witch trials in the Medebach office. Pp. 137-176

- Rainer Decker: The persecution of witches in the Duchy of Westphalia pp. 189–218

- R. Fidler: Sources on the persecution of witches in Werl / Westphalia in: ders .: Rosary altar and pyre. The rosary retable to Werl / Westphalia (1631) in the field of denominational politics, Marian piety and Hexenglaube, Cologne 2002, pp. 129-136 online version

- Peter Arnold Heuser: The Electoral Cologne witch trial ordinance from 1607 and the cost ordinance from 1628. Studies on the Cologne witch ordinance part II (distribution and reception). In: Westfälische Zeitschrift Vol. 165 2015 pp. 181–256.

- Tobias A. Kemper: "... the still growing blooming youth as a hideous example ..." Child witch trials in Oberkirchen (Duchy of Westphalia). In: SüdWestfalen Archive. Volume 4/2004, pp. 115-136

- Tobias A. Kemper: The witch trials in the office of Fredeburg. With an appendix on witch trials in neighboring judicial districts. In: SüdWestfalen Archiv 16 (2016), pp. 74–129.

- Rainer Decker: The witch hunts in the Duchy of Westphalia. Research status, sources and objectives. In: Westfälische Zeitschrift No. 132/133, 1981/82, pp. 339–386 ( online version of the article from the Landschaftsverband Westfalen-Lippe (LWL) , accessed on April 28, 2016)

- Rainer Decker: Opponent of the great witch hunt in the Duchy of Westphalia and in the Hochstift Paderborn. In: Hartmut Lehmann ; Otto Ulbricht (ed.): From the mischief of the witch trials. Opponents of the witch hunt from Johann Weyer to Friedrich Spee. Wiesbaden 1992, pp. 187-198

- Tanja Gawlich: The witch commissioner Heinrich von Schultheiß and the witch persecution in the Duchy of Westphalia. In: Harm Klueting (Hrsg.): The Electoral Cologne Duchy of Westphalia from the beginnings of Cologne rule in southern Westphalia to secularization in 1803. Münster 2009, ISBN 978-3-402-12827-5

- Gerhard Schormann: The war against the witches. The extermination program of the Electors of Cologne. Göttingen 1991

- Martin Vormberg: The magic trials of the court of Cologne, Bilstein 1629-1630 , series of publications of the district of Olpe No. 38. Ed. By the district administrator of the district of Olpe and the district home association of Olpe. Olpe 2019. ISSN no .: 0177-8153

Individual evidence

- ↑ Wolfgang Behringer (Ed.): Witches and witch trials in Germany . 4th edition Munich 2000, p. 188, Wolfgang Behringer: Hexen. Faith - Persecution - Marketing . Munich 1998, p. 55, Rainer Decker: The persecutions of witches in the Duchy of Westphalia , p. 199, Gerhard Schormann: Witches trials in Germany. Göttingen , 1996, p. 65, Gudrun Gersmann: Neue Herren - Westfälische Geschichte 1648-1770 online presentation

- ↑ Wolfgang Behringer (Ed.): Witches and witch trials in Germany . 4th edition Munich 2000, pp. 130f.

- ^ A b Tanja Gawlich: The witch commissioner Heinrich von Schultheiß and the witch persecution in the Duchy of Westphalia. In: Harm Klueting (Ed.): The Electoral Cologne Duchy of Westphalia from the beginnings of Cologne rule in southern Westphalia to the secularization in 1803. Münster 2009, p. 299f.

- ^ Rainer Decker: The witch hunts in the Duchy of Westphalia. In: Westfälische Zeitschrift 132/133 1981/82, p. 190

- ↑ Elvira Toplaovic: "Ick kike in die Stern vndt versake Gott den herrn". Verbalization of the devil's pact in Westphalian interrogation protocols of the 16./17. Century. Online version (PDF .; 650 kB)

- ^ A b c d Rainer Decker: The witch hunts in the Duchy of Westphalia. P. 192.

- ↑ to Bilstein: Otto Höffer: The witch hunt in the office of Bilstein. Pp. 119-136.

- ↑ Klemens Stracke: When the pyre blazed. From the witch craze in the Bilsteiner Land. In: Voices from the Olpe district. 73rd episode, 1968, pp. 139–175, Rainer Decker: The persecutions of witches in the Duchy of Westphalia. S. 193f., To Oberkirchen: Alfred Bruns: The Oberkirchener witch protocols. P. 11–90, on Hallenberg: Georg Glade: Rehabilitation of the victims of the witch madness in Hallenberg. Online version (PDF .; 75 kB)

- ↑ to: Ralf-Peter Fuchs : Honor and Reputation. Lexicon of witch research

- ↑ About this: Ralf-Peter Fuchs : The accusation of sorcery in the legal practice of the Injurienververfahren. A comparison of some Reich Chamber Court trials of Westphalian origin. In: Journal of Modern Legal History 17/1995 p. 4.

- ↑ Ralf-Peter Fuchs : The charge of sorcery in the legal practice of the Injurienververfahren. A comparison of some Reich Chamber Court trials of Westphalian origin. In: Zeitschrift für Neuere Rechtsgeschichte 17/1995 p. 9f .; Magdalena Padberg: An extraordinary witch trial. From Esleve versus Volmers / Hoberg. Arnsberg 1987.

- ↑ Quoted from: Wolfgang Behringer (Hrsg.): Witches and witch trials in Germany . 4th edition Munich 2000, p. 238.

- ↑ Tanja Gawlich: The witch commissioner Heinrich von Schultheiss and the witch persecution in the Duchy of Westphalia. P. 301, on the reception of Carolina in witchcraft law: Michael Ströhmer: Carolina (Constitutio Criminalis Carolina, CCC) The embarrassing neck court order of Emperor Charles V in the context of the early modern witch trials. Lexicon of witch research

- ↑ Quoted from: Rainer Decker: The persecution of witches in the Duchy of Westphalia. P. 195.

- ^ Rainer Decker: The witch hunts in the Duchy of Westphalia. P. 195.

- ↑ Tanja Gawlich: The witch commissioner Heinrich von Schultheiss and the witch persecution in the Duchy of Westphalia. P. 302.

- ↑ Tanja Gawlich: The witch commissioner Heinrich von Schultheiss and the witch persecution in the Duchy of Westphalia. ; Rainer Decker: The witch hunts in the Duchy of Westphalia. P. 196.

- ↑ reprinted in: Hermann Löher: Hochnötige Unterthanige Wemütige Klage Der Pious Invalid. 1676 online version .

- ↑ Wolfgang Behringer (Ed.): Witches and witch trials in Germany . 4th edition Munich 2000, pp. 301f.

- ↑ a b Rainer Decker: The witch hunts in the Duchy of Westphalia. P. 199

- ↑ cf. to Fredeburg: Tobias A. Kemper: The witch trials in the office of Fredeburg. With an appendix on witch trials in neighboring courts. In: Südwestfalenarchiv 2016, pp. 75–129.

- ↑ to Werl: R. Fidler: Sources for witch persecution in Werl / Westphalia. Online version (PDF .; 120 kB)

- ^ Alfred Bruns: The Oberkirchen witch protocols. P. 26ff.

- ↑ a b Tobias A. Kemper: "... the still growing blooming youth as a hideous example ..." Child witch trials in Oberkirchen (Duchy of Westphalia). In: SüdWestfalen Archiv vol. 4/2004 pp. 115–117.

- ↑ a b Rainer Decker: The witch hunts in the Duchy of Westphalia. P. 201f.

- ↑ Heinrich von Schultheiß: An Detailed Instruction As in Inquisition Matters of the Increased Vice of Magic against The Magic of the Divine Majesty and of Christendom's enemies without the risk of the innocent to proceed ... Cologne 1634, p. 467

- ^ Rainer Decker: The witch hunts in the Duchy of Westphalia. P. 200

- ↑ Gerhard Schormann: The war against the witches. The extermination program of the Electors of Cologne. Göttingen 1991, p. 9, Wolfgang Behringer: Witches: Faith, persecution, marketing. Munich 1998, p. 55, Wolfgang Behringer (Hrsg.): Witches and witch trials in Germany. 4th edition Munich 2000, p. 188

- ^ Rainer Decker: The Arnsberg witch judge Dr. Heinrich von Schultheiss (approx. 1580–1646). In: Arnsberger Heimatblätter vol. 16/1995, pp. 22-35, Tanja Gawlich: The witch commissioner Heinrich von Schultheiß and the persecution of witches in the Duchy of Westphalia. Pp. 310-315

- ^ Franz Ignaz Pieler: Life and work of Caspar von Fürstenberg according to his diaries. Also a contribution to the history of Westphalia in the last decade of the 16th and the beginning of the 17th century. Paderborn 1873, p. 99f., Magdalena Padberg: An extraordinary witch trial. From Esleve versus Volmers / Hoberg. Arnsberg 1987, p. 187, Hartmut Hegeler : witch prison for Arnsberg mayor. In: Sauerland 2/2011, pp. 72–75

- ^ Rainer Decker: Pastor Michael Stappert (Hirschberg / Grevenstein) - the Friedrich Spee of the Sauerland. In: Michael Senger (ed.): Thirty Years War in the Duchy of Westphalia. Schmallenberg 1998, pp. 45–51, Rainer Decker: Opponents of the great witch hunt in the Duchy of Westphalia and in the Hochstift Paderborn. In: Hartmut Lehmann; Otto Ulbricht (ed.): From the mischief of the witch trials. Opponents of the witch hunt from Johann Weyer to Friedrich Spee. Wiesbaden 1992, pp. 187-198

- ^ Judgment of the Reichskammergericht 1632 against Kurköln, printed in: Wolfgang Behringer (Ed.): Witches and Witches Trials in Germany. 4th edition Munich 2000, pp. 390-394

- ^ Rainer Decker: The witch hunts in the Duchy of Westphalia. P. 209f.

- ^ Rainer Decker: The witch hunts in the Duchy of Westphalia. P. 210f.

- ↑ cit. after: Wolfgang Behringer (Ed.): Witches and witch trials in Germany. 4th edition Munich 2000, p. 399

- ↑ on the Brilon case: Gerhard Brökel: Accused in puncto magiae. Witch trials around 1685 in Brilon. In: Südwestfalenarchiv 12/2012 pp. 25–50

- ^ Rainer Decker: The witch hunts in the Duchy of Westphalia. P. 211f.

- ^ Rainer Decker: The witch hunts in the Duchy of Westphalia. P. 212

- ^ Rolf Schulte: Men in witch trials - an overview from a Central European perspective. Online version , Rainer Decker: The persecution of witches in the Duchy of Westphalia. P. 212

- ^ Rainer Decker: The witch hunts in the Duchy of Westphalia. P. 212, der .: Rainer Decker: The social background of the witch hunt in the court of Oberkirchen. Pp. 98-101

- ↑ Local Board Rüthen: Bill No. 017/11. Westfalen-heute.de witch trials: Rüthen wants to rehabilitate victims ( Memento of 14 May 2011 at the Internet Archive ) accessed 18 November 2011

- ↑ City of Sundern, template No. 0292 / VII of April 18, 2011 (PDF; 337 kB) accessed on November 13, 2011

- ^ Sauerlandkurier ( memento of February 17, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) of February 13, 2011

- ↑ List of places with witch monuments in Westphalia ; Hartmut Hegeler: Witch monuments in the Sauerland. In: Sauerland 4/2008, pp. 173-181; Hexenturm in Rüthen