Hospitalhof Stuttgart

The Hospitalhof Stuttgart is the spiritual center of the Evangelical Church in Stuttgart. It unites under one roof:

- an administration and meeting center with offices for numerous offices of the general parish and the regional church

- and the Hospitalhof education center with eight seminar and conference rooms, the "education flagship of the Protestant Church", a "center for education, culture and spirituality".

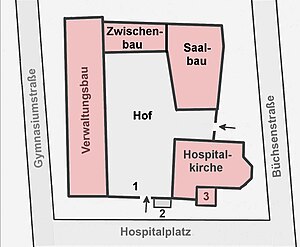

The four-wing complex of the hospital courtyard encloses an inner courtyard and consists of the hospital courtyard building and the remains of the hospital church , which was partially rebuilt after the destruction of the Second World War.

The building was added to the hospital church in 2012–2014 according to the plans of the architects Lederer Ragnarsdóttir Oei (LRO) . Clinker bricks produced using the water-struck method were used to establish a connection with the existing building. The hospital courtyard and church are located "in the heart of the city" in a central square of the chessboard-like hospital district, a district on the western edge of the city center.

The hospital courtyard was built on the site of a former Dominican monastery from the late 15th century, which was used as a hospital from 1536 to 1895 after the secularization and then served as a police building and prison. After the destruction in World War II, Wolf Irion (1909–1981) built the old hospital yard on the property in 1960, which had to be replaced by a new building in 2014.

Hospitalhof education center

The Hospitalhof Education Center is the center of the Evangelical Church in Stuttgart for education, culture and spirituality. Basic humanistic convictions shape the work of the Hospitalhof:

- “Those who think together and think further, get to know the other. That is why personal encounters, openness to those who think differently and an interest in those I don't know are part of the basic understanding of an education center. "

- “We are convinced that different opinions, cultural and religious influences, language and origins enrich us and allow us to see further, think further and get ahead. Education is a matter of the heart of the Reformation. "

Mission statement

The basis of the work is the Christian image of man. As a house of encounters, the Hospitalhof has set itself the goal of a non-prejudiced and open culture of discussion. The approximately 350 events in the Hospitalhof are attended by thousands of people every year. In lectures, seminars and pastoral discussion groups "the most important social, political, scientific, cultural, theological and spiritual issues are negotiated". In addition, the Hospitalhof organizes concerts and highly regarded exhibitions on contemporary art.

Eight seminar and conference rooms (see also rooms ) are available for events in the Neuen Hospitalhof . The art exhibitions take place in the two long corridors on the ground floor, where the cloisters used to be.

New hospital courtyard

The content-related and organizational work at the Hospitalhof is carried out by full-time and voluntary employees. Pastor Monika Renninger (* 1961) has been running the Hospitalhof since 2013, and she says that at this location "it becomes noticeable that the evangelical church lives from the vastness in thinking and interests".

To introduce the New Hospitalhof, Monika Renninger, the director of studies at the Rolf Ahlrichs Education Center and the pastor of the Hospital Church Eberhard Schwarz looked back and looked at the education center again:

- “In the upheavals of our time and society, we not only need openness, flexibility and the willingness to get involved in something new ... we also need places of reliability, places to learn to live and areas of experimentation for a new, binding life. The new hospital courtyard should and will be such a place again. "

- “The Hospitalhof has been firmly established in Stuttgart culture for a good thirty years and is of great importance in the educational landscape beyond the churches. That is the building work of Prelate i. Thanks to R. Martin Klumpp and the expansion work by Pastor Helmut A. Müller. "

- Conversations with science, encounters with the arts, questions of psychology, health and participation in social life for all people have their excellent place at the Hospitalhof. “Lectures, seminars and workshops help to shape life transitions and overcome life crises. The interreligious conversation as well as current political and ethical questions are part of the program, and of course the philosophical and theological interpretations of man and the world. The program at the Hospitalhof reflects the insight that knowledge and an understanding of the world alone are not enough for a successful life; it also needs personality and heart formation so that people can cope with themselves and with what is around them and become beneficial and prosperous Contribute to living together. "

history

Development under Martin Klumpp

In 1979 Martin Klumpp (* 1940) took over the position of pastor at the Hospital Church and one year later founded the Evangelical Education Center Hospitalhof Stuttgart. In founding this educational institution, he was guided by the following principles:

- “When faith makes us mature, then interest in the world and its problems grows. Those who know more can have a better say in decisions. "

- "It was important to me that the Stuttgart region not only developed economically, but that social, cultural, ecological and spiritual aspects were also included."

Over the years Klumpp has been able to win many important speakers for the Hospitalhof, including Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker , Elisabeth Kübler-Ross , Ruth Cohn , Viktor E. Frankl , Carl Rogers , Paul Watzlawick , Alexander Mitscherlich , Heinrich Albertz , Stefan Heym , Bülent Ecevit , Hilde Domin , Ernst Käsemann and Gerhard Ebeling .

According to Martin Klumpp, the Hospitalhof is “a nucleus from which, for example, the hospice work, the Vesper church , the Johannes Brenz primary school and the church in the city grew.” The hospice work is organized in the Stuttgart hospice, which is the “accompaniment of seriously ill and dying people and their relatives ”. The Evangelical Church in the City of Stuttgart is an amalgamation of the three inner-city churches Stiftskirche , Leonhardskirche and Hospitalkirche, which "with their different worship and spiritual offers invite you to celebrate and experience the Christian faith in evangelical freedom and tradition".

Expansion under Helmut A. Müller

When Klumpp changed pastor in 1986 and took office as dean of Stuttgart, Helmut A. Müller followed him as pastor of the Hospital Church and as head of the Hospitalhof, which he headed until 2013. He organized more than 10,000 events and over 200 exhibitions in the Hospitalhof and the Hospital Church, "where he primarily offered young artists a platform, but also brought international artists to Stuttgart, such as Jonathan Meese , Tobias Rehberger and Christian Jankowski ".

Under Helmut A. Müller, the Hospitalhof once again experienced a significant boost in further development: “The growing number of events and participants is impressive evidence of the increasing importance of the Hospitalhof. In addition, Müller's focus on »Contemporary Art at the Hospitalhof« has made it known far beyond the borders of Stuttgart. "

Hospital district

The Hospitalhof with the main entrance at Büchsenstrasse 33 is located on the western edge of downtown Stuttgart, in the Stuttgart-Mitte district . The Dominican monastery was originally located at this point is the center of the Count Ulrich V of Württemberg founded new suburb , also called the tournament field suburb , then Upper and rich suburb had been dedicated to the monastery church, Mary, Our Lady suburb was called . The quarter was laid out like a chessboard based on the example of Turin , a structure that has been preserved to this day. It comprised the area that essentially corresponds to the triangle between Fritz-Elsas-Strasse in the southwest, Schloßstrasse in the northwest and Theodor-Heuss-Strasse in the southeast. After the Dominican monastery was closed by Duke Ulrich in the course of the Reformation on February 5, 1536 and the monastery building was handed over to the city with the requirement to set up a hospital there, in which the old and the poor were to be entertained, this was done 170 years earlier by Katharina von Helfenstein , the wife of Count Ulrich IV. von Württemberg am Obertor, at today's Wilhelmsbau, relocated the hospital. The "Bürgerhospital" created in this way became the cradle of the Stuttgart hospital. The surrounding neighborhood was since that time Spital- or hospital district called.

In 1938, the Old Synagogue at Hospitalstrasse 36, not far from the Hospitalhof , was destroyed in the November pogroms , and during the Second World War, apart from the Hospital Church and the former monastery building, most of the old half-timbered houses in the district fell victim to the bombs, so that almost after the war the entire neighborhood had to be rebuilt. In 1952 a synagogue was rebuilt at the old location, the destroyed former Dominican monastery was replaced by the (old) hospital courtyard, which was completed in 1960, and the rest of the district was rebuilt with a mixed development of residential, commercial and office buildings. Today the hospital quarter is mainly an office and business quarter with shops, restaurants, hotels, banks, insurance companies, schools, offices and associations, social, cultural and church institutions.

“The advantage of being in the immediate vicinity of the temple of the muses» Liederhalle «, the university, the art association and almost all authorities, clinics and department stores is a considerable burden in the residential area. a. by the car traffic in the city center opposite. ”In addition, there is the influx of night owls from the neighboring party mile on Theodor-Heuss-Straße , leaving mountains of rubbish behind and not shrinking from desecrating and polluting the Reformation monument .

City map of Stuttgart, Matthäus Merian , 1643. - Above: the checkerboard-like Reiche Vorstadt, middle: old town, below: Leonhardsvorstadt.

|

Surroundings

Only a few buildings in the hospital district survived the horrors of World War II or the “demolition fury” of the city. One of the last old buildings, the at least 350 year old Wengerterhaus at Firnhaberstraße 1, survived several centuries unscathed and was abandoned in 2012 in favor of a modern investment project. Of the approximately 80 buildings in the hospital district, only two were built before the Second World War: the Haus der Wirtschaft and the Büchsenstrasse 28 (see below, House C).

The immediate vicinity of the Hospitalhof "is as faceless as any other outskirts of the sixties". Through the random juxtaposition of different architectural styles, it reflects the wild growth in the development of the district after the Second World War:

- The more than 100 year old house at Büchsenstraße 28 (C) was built by the architects Eisenlohr & Weigle "contemporary and modern in a classicist Art Nouveau" and is the highlight among the neighboring houses of the Hospitalhof.

- Some buildings date from the 1950s. They have plastered facades and tiled hipped roofs (E, I, L).

- Some more modern buildings have plastered facades and flat roofs (F, G, H, K).

- A few modern commercial and residential buildings have facades made of exposed concrete (A, B) or glass and metal (D, J).

|

|

|

| Site plan of the hospital courtyard and the neighboring buildings. Legend: A – L: neighboring building (clockwise), 2-digit number: house number, 4-digit number: year of construction (if known). |

|

Hospital place

The Hospitalplatz was previously planted with a chestnut avenue (see map), of which only one of the two rows in front of the south facade of the Hospital Church remained. The nine trees cover and hide the south facade of the church and the Reformation monument behind them. The character of the hospital square is no longer recognizable.

In 2010 Arno Lederer called for the facade and the Reformation monument hidden behind chestnut trees to be exposed. The trees felled for this should be replaced by a row of trees on the opposite side of the street. According to Lederer, the historic sandstone facade with the empty tracery windows could have been seen better and the “non-commercial exclave of the city” could have been enlarged with the wider green border.

From 2015 the hospital square was redesigned to a purely pedestrian area, but the chestnuts were not moved.

building

Architectural principles

When planning architectural objects, the architecture firm Lederer Ragnarsdóttir Oei (LRO) is guided by the basic conviction that it is the task of the architects to counteract the “inhospitableness of our cities”, that is, to give architecture a humane face.

"First the city, then the house"

Buildings are usually not perceived as solitaires, but as part of their surroundings. One should therefore assume that an architect who builds new things in a grown environment or renews the old is aware of this and shows respect for what is already there. Based on this conviction, LRO wrote the motto "First the city, then the house" on the flags:

- “A building is always only part of a whole: part of the landscape, part of the city in which it is located. And so we understand the task that has fallen on us not as one that relates solely to the building that is to be built, but as a contribution to the city and the surrounding area in which it is located. "

- “An old saying goes that the church, town hall and school are among the special buildings that shape the city. So they have been promised not to have to submit to the style and order of the "normal" houses of the township. "

The disparate architecture of the hospital district would not have given the architects any point of departure for adapting to the surroundings. Rather, it was her endeavor to restore the square around the Hospital Church to its original meaning as an area that shaped the cityscape. The following measures were used for this purpose:

- "Restoring the building dimensions to the former alignments, ... that is, the twisting of the system in the city plan", or as Wolfgang Bachmann puts it: "The alignments of the new building legs resist the good street grid all around."

- Extension of the "torso of the church wall to the original extent".

- The hallways on the ground floor and the inner courtyard are based on the former cloisters.

- In the inner courtyard, six hornbeam pillars , “exactly where the pillars of the church used to be”, and an elongated, rectangular concrete bench remind of the lost nave . A square of strictly lined-up standard roses in the other half of the courtyard evokes motifs from the former monastery garden.

- “The masonry made of light bricks” is a reminiscence of the former “character of the inner-city ensemble, as the historical nucleus of the quarter”.

"Inside is not outside"

Modern glass facades, which are almost typical of contemporary building activity in Stuttgart, have no place in LRO's architectural canon . According to the principle "Inside is not outside", LRO uses conventional perforated brick facades instead of the ubiquitous glass facades , which seem " familiar to us at first glance":

- “We don't like the transparent glass covers that much. Why should we go into buildings that tell us when we enter: you're outside again. "

- “Outside is outside and inside is inside. Over the centuries, architecture has shown an infinite number of beautiful rooms, which get their quality through the economical use of openings, which are wider and more exciting than you initially suspected from the outside due to the way they light. "

Value, durability, sustainability

The use of "closed facades made of masonry or concrete with appropriate insulation" offers the following advantages , according to LRO :

- "Compared to those made of glass and metal, closed facades are ... cheaper to manufacture than those made of glass and metal."

- The long-term advantages of closed facades relate to "durability, maintenance, but also the lower cost of repair."

Layout

| Floor plans |

|---|

| ground floor |

| 1st floor |

| 2nd Floor |

The L-shaped floor plan of the New Hospitalhof overlies the floor plan of the old Dominican monastery. The elongated building block on Gymnasiumstrasse corresponds to the former west wing. It is connected at right angles to a part of the building that is twice as wide, which was built over the former north wing and part of the east wing and, due to its excess width, also occupies a strip of the former monastery courtyard.

“The new hospital courtyard takes up the contextual and architectural connection between church and hospital courtyard, supplemented by the administration building like the farm building once in the monasteries. With this monastic floor plan of the entire building, which the architects Lederer Ragnarsdóttir and Oei have rotated slightly offset into the area of the area, a place has been redefined that "falls out of the ordinary" in the best sense of the word. "

On the ground floor, the rooms face the street, so that the corridors on the inside face the inner courtyard like the former cloister walkways.

“The almost square floor plan also accommodates the desire for multiple uses. The hall is, so to speak, the core of the facility, around which the other rooms are grouped in plan and section. "

Spaces

Although the Hospitalhof fulfills an urban planning function for the hospital district and stands for itself as a work of art, its main purpose is to provide space for the education center and offices for the more than 100 employees of the Protestant church administration.

Meeting and seminar rooms

Eight halls are reserved for educational work and for conferences. Four halls on the ground floor are entwined around the corridor that is reminiscent of the old monastery cloisters: three smaller conference rooms on Gymnasiumstraße for 18-66 people and the "Small Hall", the Elisabeth-und-Albrecht-Goes, illuminated by striking triangular windows Hall on the through lane to the YMCA house for a maximum of 176 people. There is also a “salon” on Büchsenstrasse that can serve as a cafeteria. Since the house does not have its own catering facilities, it is managed by service companies if required. Two further conference rooms are located on the third floor.

Great Hall

The Elisabeth and Albrecht Goes Hall is located directly below the “Great Hall”, the Paul Lechler Hall on the first floor. Together with the associated gallery , this extends over two floors and offers space for a maximum of 612 people. The stage area is illuminated by 3 × 13 light eyes, which also give the Paul-Lechler-Saal a striking face to the outside. The auditorium impresses with a glass-covered, curved lamellar ceiling through which the zenith light streaming in illuminates the hall as bright as day. The hall is adjoined by a foyer with a seating area that looks out onto Büchsenstrasse and invites guests to chat.

The Paul-Lechler-Saal is not only the central location of the hospital courtyard because of its size. The design of the hall arouses a feeling of solemnity and wellbeing without being ostentatious:

- “The large hall in the new building looks as festive as the Dominican Church used to be. It is vaulted, resembling the inverted hulls of a Venetian church, a lamellar construction that contains a huge skylight. Like them, the back wall of the stage is made of amber-colored maple wood; simply white, on the other hand, the hall and gallery, to which the wine-red floor covering forms a pleasantly invigorating contrast. "

- "The hall aroused enthusiasm at the inauguration - a more beautiful one has not been built in Stuttgart in recent times."

Room names

“The Dominicans have always been valued for their sermons and known as initiators not only for spiritual, but also secular education. This tradition continued in the names that were associated with the church in the future: the humanist Johannes Reuchlin (1455–1522), the church and school reformer Johann Valentin Andreae (1586–1654), the later prelate and famous preacher Karl Gerok ( 1815–1890), to name just a few. "

The conference and seminar rooms were named after these and other prominent personalities who worked in Stuttgart:

- Countess Katharina von Helffenstein, (before 1536–1594), wife of Ulrich IV. Count von Württemberg , founder of the St. Katharina Hospital

- Johannes Reuchlin (1455–1522), humanist

- Johann Valentin Andreae (1586–1654), church and school reformer

- Karl Gerok (1815–1890), pastor (also at the Hospital Church) and poet

- Käte Hamburger (1896–1992), literary scholar and philosopher

- Paul Lechler (1849–1925), entrepreneur and social reformer

- Albrecht Goes (1908–2000), pastor and writer

- Elisabeth Goes (1911–2007), wife of Albrecht Goes, " Righteous Among the Nations "

window

| 1 | Triangular window, Gymnasiumstrasse, ground floor . |

| 2 | Rectangular window with roof , Heustraße, 2nd – 4th centuries 1st floor . |

| 3 | Pointed arched window with cross blades made of wood, hospital space, ground floor and first floor. |

| 4th | French windows with roofs , red blinds and balustrade grille, Gymnasiumstraße, 1st – 4th floor 1st floor. |

| 5 | 3 lines with 13 light eyes each, outside with concrete frame and shade, inside with folding flaps, Heustraße, 1st floor, Paul-Lechler-Saal. |

| 6th | One light eye per floor, with brick frame, metal window sill and glass window, south-eastern courtyard facade. |

| 7th | Square window, Gymnasiumstrasse, EG. |

| 8th | Window box, Büchsenstrasse, stairwell, one each in the 1st – 3rd 1st floor. |

| 9 | Square window with longitudinal wooden slats, Hospitalplatz, 3rd floor. |

| 10 | French windows with wooden frames and balustrade lattice, north-western courtyard facade, 1st floor. |

| 11 | Seating bay with double rectangular window, foyer of the Paul-Lechler-Saal, 1st floor. |

| 12 | Transverse rectangular window with fixed longitudinal slats made of brick, Heustraße, 1st floor. |

The architects' wealth of ideas is also noticeable in their window range. They were not satisfied, as is often the case, with a few rectangular shapes of different formats, they rather drew on a diverse repertoire of window types with different characteristics:

- Shapes: triangle, rectangle, square, circle

- Frame: brick, wood, metal

- Privacy and sun protection: transverse and longitudinal slats made of wood and bricks, light eye umbrellas, roller blinds.

The Stuttgart city dean Søren Schwesig also sees a symbolic component in the rich window furnishings of the hospital courtyard: “The windows and inner courtyard are particularly impressive about the new hospital courtyard. The message is: light and fresh ideas in, widen your view. The Hospitalhof is not an »ivory tower«, but stands in the middle of life. "

Pointed arch window

For the construction of the old hospital courtyard, the south facade, which had been preserved after the war damage, was shortened by two bays . To "heal" this historical amputation, LRO rebuilt the two lost yokes without replicating them. The south wall of the church was thus restored to its original length, so that it now again fills the entire length of the square on Hospitalplatz.

Like the rest of the hospital courtyard, the facade of the two new bays is clad with light-colored bricks, which contrast sharply with the age-dark yellow sandstone of the old south facade. Like the old bays, the windows are equipped with pointed arches, buttresses and coffin cornices , but dispense with Gothic tracery and hide the escape staircase behind them with wooden cross slats.

Triangular window

Ten windows arranged in a row on Gymnasiumstrasse illuminate the four halls on the ground floor. They are designed as isosceles, "sugar-hat-shaped" triangles or like a capital A ("A window"), are framed on the outside by narrow concrete strips and a metal window sill, on the inside by wooden profiles (the middle part of the three-part window can be opened inwards become).

The otherwise seldom encountered triangular shape of wall openings has almost become a distinguishing feature for LRO . The triangles basically have a rounded tip, their height extends up to a single or double storey height, they can be isosceles or equilateral, their tip can point upwards or downwards, the rounding can be more pointed like a sugar loaf or blunt like a Arches , and finally the triangles can be implemented as windows or as arcades .

Light eyes

Porthole-like light eyes are often found in contemporary buildings. They are used as windowless decorative elements or as glazed light sources. The stage of the Paul-Lechler-Saal is illuminated by 3 rows with 13 light eyes each, which look out to the neighboring YMCA house as if in rows. The light eyes are shaded on the outside by thick, crooked “sun brims” made of concrete. Inside, they are closed by two semicircular wooden folding flaps that can be opened and closed like butterfly wings.

The head of studies at the Hospitalhof, Rolf Ahlrichs, sees the light eyes as a symbol for the work of the education center: “The understanding of education is expressed, among other things, in the holes ... which are also reflected in the architecture of the new building. These holes illustrate: There are at least 39 perspectives on a subject. ... We stand here for the fact that there is a multitude of opinions and that everyone can develop their point of view. "

patio

layout

The inner courtyard occupies roughly the space between the former cloisters (see floor plan of the hospital courtyard). It consists of two unequal halves, a smaller northern and a larger southern part:

- The entrance gate on Büchsenstrasse opens into the northern half of the inner courtyard, a rectangular field that extends to the opposite wing of the building. It encloses an elongated square of 5 × 12 standard roses, which is reminiscent of the former monastery garden. An elongated, cuboid-shaped concrete bench the width of the Rosencarrées forms the end.

- The southern half of the inner courtyard borders on the east facade of the Hospital Church and its former south facade. The floor is covered with light fine gravel. Six hornbeam columns , "exactly where the columns of the church used to be", are reminiscent of the lost nave.

|

|

| Floor plan of the hospital courtyard. 1. South facade of the Hospital Church, 2. Reformation monument, 3. Church tower. Patio. View of the former south facade of the Hospital Church. View from the entrance to the north inner courtyard with rose garden and concrete bench. South inner courtyard with column hornbeams. Left: Hospital Church. Back: south facade. |

Baptismal font

When the Hospital Church was granted baptism rights in 1809, a baptismal font made of local sandstone was set up in the church in front of the altar. After the church was largely destroyed in an air raid on September 12, 1944, the ruins of the nave, including the baptismal font, were moved into the forest of Mietholz in the Sindelfingen Forest in 1948 . Heinrich Spring, then a forester at the Katzenbacher Hof , used some of the rubble to create forest paths.

He saved the baptismal font, the original base of which had been lost, and in 1958 placed it upside down as a memorial on a cuboid memorial stone with the inscription “ sic transit gloria mundi ” (this is how the world's glory passes), surrounded by three large stone cuboids from the old hospital church, which were used by walkers to rest.

On September 12, 2014, the 70th anniversary of the air raid, the font was recovered, thoroughly restored and given a new base. On October 3, 2014, it was put up again in the courtyard of the hospital courtyard, where the main nave of the church used to be. The installation on a wooden pallet seems to indicate that it is a temporary installation site. It is possible that the baptismal font will be returned to its old place in front of the altar after the renovation of the hospital church, which is due to be completed in 2016.

history

The New Hospitalhof from 2014, like the Old Hospitalhof from 1960, stands on the grounds of a former Dominican monastery, which was located in a central square of the hospital quarter, which is laid out like a chessboard and grouped around a rectangular monastery courtyard. The cloister courtyard was surrounded by four cloister wings , the southern wing was connected to the nave of the hospital church.

The cloister square was not parallel, but slightly tilted to the surrounding streets. The question of why is not clear among historians. Wolf Irion (1909–1981) did not build the old hospital courtyard at an angle, but parallel to the streets in the area. For Arno Lederer, however, when building the new hospital courtyard was “the return of the building dimensions to the former lines that the Dominican monastery had taken, ie the Rotation of the system in the city plan ”decisive.

- Scheme floor plans of the hospital church and the hospital courtyard

founding

The founder of the Hospital Church and the associated Dominican monastery was Count Ulrich the Well-Beloved . The hospital church emerged from the small chapel “Our dear women”, built in 1470, and was named “Our dear wife and St. Ulrich” after this chapel and Count Ulrich's patron saint.

When the Dominican monastery was founded in 1473, only the choir of the church was completed, the construction of the church was not completed until 1493. The church had no tower, but only a roof turret over the choir roof, as was customary in churches of mendicant orders . It was not until 1730–1738 that a tower was added to the church. The monastery was also opened in 1473, but was not completed until 1504.

secularization

After the introduction of the Reformation in Württemberg, the monastery church was converted into a Protestant church in 1536. The monastery was secularized and given to the city by Count Ulrich with the condition that the St. Catherine Hospital be accommodated in the monastery buildings . This was previously housed in a building in the Breite Straße, which was "very narrow and very dangerous because of the fire" and could not be extended. After the hospital moved in, the church was renamed the Hospital Church.

19th century

In 1820 the foundation stone for a new hospital was laid and the previous St. Katharinenhospital was renamed the Bürgerhospital , so that the new hospital could be baptized in the name of the late Queen Katharina.

In 1892–1894, a new building was erected between Tunzhofer Strasse and Wolframstrasse instead of the community hospital, which had been structurally renewed and enlarged between 1839 and 1844 and had partly received a third floor. The city had already set up offices in the monastery wings before, "from 1895 to 1922 the Stuttgart City Police Office was housed there, and afterwards the State Criminal Police Office, Section II of the Stuttgart Police Headquarters". In 1894, a city police prison was set up in the former monastery, the so-called “Büchsenschmiere”, which gained fame during the Nazi era .

In 1917 the Reformation Monument was erected on the south facade of the church on the occasion of the four hundredth anniversary of Luther's posting of the theses .

Old lapidary

At the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, around 200 houses in Stuttgart's old town were demolished in order to renovate the old town and make space for new buildings. During the demolition work, the artistically valuable components were collected and from 1905 stored in the cloister of the former Dominican monastery. This was the foundation of the first urban lapidarium .

time of the nationalsocialism

“After 1933, the rooms functioned as a prison in which Jewish citizens, Sinti and Roma, communists and unpopular Christians were imprisoned and tortured.” “In the autumn of 1938, Jews of Polish nationality living in Stuttgart and the surrounding area were rounded up here and then pursued Deport Poland. The same thing happened in the war with the Sinti and Roma before their deportation to concentration and extermination camps in the east. "

War destruction

During the Second World War, the hospital church and the remaining former monastery buildings were largely destroyed in the night of September 12th to 13th, 1944. Of the hospital church, only the choir walls, the south facade, the west facade and part of the tower remained to some extent. The lapidarium holdings were also lost, with the exception of a few objects.

reconstruction

After the Second World War, the largely destroyed Leonhardskirche was rebuilt until 1950, while the fate of the Hospital Church remained uncertain. The remaining segments of the choir stalls with 57 of the original 87 seats were set up in the Leonhardskirche, where they remained even after the partial reconstruction of the hospital church.

It was not until 1956 that the partial reconstruction of the Hospital Church based on plans by Rudolf Lempp and the construction of the Old Hospital Courtyard based on plans by Wolf Irion (1909–1981) were decided.

Old hospital courtyard

The two-and-a-half-wing building of the old hospital courtyard was built over the ground plan of the former Dominican monastery. It consisted of an administration building, an intermediate building and the hall building. The preserved west facade of the church and two yokes of the south facade were demolished to make room for the administration building, which was erected as a five-story building on Gymnasiumstrasse and stretched the entire length of the block. It was connected via a two-storey intermediate building to the half-length hall on Büchsenstrasse, which housed the community hall and almost reached the height of the administrative building. The entrance to the inner courtyard was located between the parish hall and the church (as it is today).

The new building of the old hospital courtyard and the partial reconstruction of the hospital church were completed in 1960. In 1979, Martin Klumpp founded the Hospitalhof education center , which has been run by Helmut A. Müller since 1986 and has been managed by Monika Renninger since 2013.

reception

Shortly after his inauguration of the New Hospitalhof found a unison enthusiastic response in the daily press and in professional journals.

The architecture critic Amber Sayah, editor for art and architecture in the culture section of the Stuttgarter Zeitung, welcomes the Neuen Hospitalhof as a refreshing counterpoint to the often synchronized contemporary Stuttgart architecture:

- “Does architecture really have to look so depressing today, asks hair-ruffling who is looking at quarters like the Europaviertel or the Gerber in Stuttgart . The answer will be - happy Easter tidings! - given elsewhere in the city: Be of good cheer, brothers and sisters, the new hospital courtyard is another spirit's child. Neither does it have those deadly boring, smooth facades, nor is it about an expected return in the form of a building structure or, as in the previous building, a house with post-war memory loss. This city has become so accustomed to its economic functionalist make-up as the norm that the exception brings to mind what we had forgotten: that architecture is able to form a place, that it does not have to look the same on all four sides as it could they stand everywhere and nowhere that they do not have to be a solipsistic , self-sufficient structure, but rather relate to their concrete surroundings and their history, that they - in a word - can make a city. "

The architecture critic and architecture historian Falk Jaeger is enthusiastic about the new building, which pays careful attention to the historic site as a lively place :

- “With their new building of the hospital courtyard, the architecture firm Lederer Ragnarsdóttir Oei is reminiscent of the square of the monastery that once stood here. With just a few tricks, architecture becomes an experience. ... The hall already aroused enthusiasm at the inauguration - a more beautiful one has not been built in Stuttgart in recent times. … Only praise can be heard throughout the house. ... Read the historical place, sensitively develop the city further, invent new forms that somehow seem familiar and fit into the context, this serving and yet imaginative, creative way of working has characterized the architects Arno Lederer , Jórunn Ragnarsdóttir and Marc Oei for years and predestines them for construction tasks where it is necessary to create something new in a historical environment. "

Wolfgang Bachmann, the publisher of the architecture magazine "Baumeister", makes no secret of his joy about the different architecture of LRO:

- “It is extremely relaxing to encounter a different architectural language according to the well-seen valid standard of reflective all-glass facades, serious natural stone hangings and solid exposed concrete housings with shifted window axes. That one understands. Anyone who is familiar with the houses of Lederer Ragnarsdóttir Oei can take thieving pleasure in collecting the rediscovered details of their earlier buildings. There are many, and if you go to the trouble, take a large sheet of paper for your notes because the déjà vu continues inside. ... We professional strollers should like the joy of playing, the desire to demonstrate their repertoire with the LRO and to add new ideas to it. "

The architecture critic of the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung Dieter Bartetzko describes the Hospitalhof as an example of "what you can learn in Stuttgart":

- The Hospitalhof “is, from the base to the flat roof, an outstandingly successful example of“ building in existing structures ”- building that is urgently needed, constantly invoked and rarely practiced. ... With all these quotations the historical dimensions are conjured up, but not fictitious. ... The island of the blessed in the ocean of dozen buildings. [You can see] how the architecture firm Lederer Ragnarsdóttir Oei recognized the essence of the quarter in the past and provided it with new impulses. The result is a respectful construction instead of ingratiating retro shapes. ... Those responsible for all of these cases [the new "city quarters" Dorotheenquartier, Milaneo , Gerber ] will have spoken of the "unique selling point" often enough. But only with the new Hospitalhof has Stuttgart created such a thing, everything else is the urban rule of self-mutilation. "

Pastor Helmut A. Müller was the second head of the hospital courtyard from 1987 to 2013. He commented on the construction and completion of the new hospital courtyard in 2013:

- “In the late 1950s, nobody had thought of an education, art and culture center when planning the old hospital courtyard. Twenty years after starting work in 1980 at the latest, it was clear that a new house had to be created for education. The fact that the lavish ideas and implementation competition for the Neue Hospitalhof was decided in favor of the architects Lederer Ragnarsdóttir Oei is one of the fortunate coincidences. With the new building on the ground plan of the former Dominican monastery, the work gets the worthy architectural framework that it has long deserved. "

literature

history

Basic literature : #Sauer 1993.1 , #Wais 1956 . Literature list: #Wais 1956.

- Hospital Church. State Conservation Office Baden-Wuerttemberg, database building research / restoration , 2012, online: .

- Karl Büchele: Stuttgart and its surroundings for locals and foreigners. Stuttgart 1858, pages 83-86.

- Otto Borst : Stuttgart. The history of the city. Stuttgart 1973, pages 59-64.

- Hansmartin Decker-Hauff : History of the City of Stuttgart, Volume 1. Stuttgart 1966, page 281.

- Hartmut Ellrich : The historic Stuttgart. Tell pictures. Petersberg 2009, pages 102-103.

- Julius Hartmann: Chronicle of the Stuttgart Hospital Church. Stuttgart 1888.

- Carl Alexander Heideloff (Ed.): The art of the Middle Ages in Swabia. Monuments of architecture, sculpture and painting. Stuttgart 1855–1864, pages 28–31, plate VII.

- Ev. Parish office of the Hospital Church Stuttgart (ed.): Festschrift for the dedication of the rebuilt Hospital Church Stuttgart on February 21, 1960. Stuttgart [1960].

- Karl Klöpping: Historic cemeteries of old Stuttgart, Volume 1: Sankt Jakobus to Hoppenlau. A contribution to the history of the city with a guide to the graves of the Hoppenlauf cemetery. Stuttgart 1991, pages 98-102, 114-119 (Hospitalkirchhof).

- Christa-Maria Mack; Bernhard Neidiger; Hartmut Schäfer: sacred space. Collegiate Church, St. Leonhard and Hospital Church in the Middle Ages. Booklet accompanying the exhibition Sacred Space. Collegiate Church, St. Leonhard and Hospital Church in the Middle Ages; 24.9. until November 26, 2004. Stuttgart 2004, pages 18-19, 34-35, 37-40.

- Harald Möhring: Ev. St. Leonhard's Church Stuttgart. Munich 1984.

- Bernhard Neidiger: Church life in late medieval Stuttgart. In: Rottenburger Jahrbuch für Kirchengeschichte Volume 17, 1998, pages 213–228, here: 220–228 (History of the Dominicans in Stuttgart).

- Bernhard Neidiger: Württemberg monastery book. Monasteries, monasteries and religious orders from the beginning to the present. Ostfildern 2003, pages 467–468.

- Winfried Nerdinger : Inside is different than outside. Lederer, Ragnarsdóttir, Oei. Exhibition in the Architektur-Galerie am Weißenhof. Baunach 2001.

- Eduard Paulus : The art and antiquity monuments in the Kingdom of Württemberg, volume: Inventare [Neckarkreis]. Stuttgart 1889, pages 20-21.

- Eduard Paulus : The gravestones found in the Hospital Church in Stuttgart in August 1878. In: Württembergische Vierteljahreshefte für Landesgeschichte Volume 2, 1879, pages 236–232.

- Paul Sauer : 500 years of the hospital church. Stuttgart 1993.

- Paul Sauer : The importance of the hospital quarter for Stuttgart's history, present and future. Speech in the Hospital Church on July 18, 2003 on the occasion of the district festival in the Hospital District. Stuttgart 2003, excerpt online: .

- Hans Schleuning (editor), Norbert Bongartz (collaboration): Stuttgart-Handbuch. Stuttgart 1985, pages 253-254, 360.

- Gerda Strecker (editor); Helmut A. Müller (Ed.): 500 years of the Stuttgart Hospital Church. From the Dominican monastery to the church in the city. Stuttgart 1993.

- The hospital church . In: Stuttgart. Guide through the city and its buildings. Festschrift for the sixth general assembly of the Association of German Architects and Engineers' Associations. Stuttgart [1884], pages 29-30.

- Gustav Wais : Old Stuttgart's buildings in the picture: 640 pictures, including 2 colored ones, with explanations of city history, architectural history and art history. Stuttgart 1951, reprint Frankfurt am Main 1977, pages 66-71, no. 48-52.

- Gustav Wais : Municipal Lapidarium (Mörikestraße 24) . In: Stuttgart's art and cultural monuments: 25 pictures with explanations of city history, building history and art history , Stuttgart [1954].

- Gustav Wais : Old Stuttgart. The oldest buildings, views and city plans up to 1800. With city history, architectural history and art history explanations. Stuttgart 1954.

- Gustav Wais : The St. Leonhard Church and the Hospital Church in Stuttgart. A representation of the two Gothic churches with explanations of architectural and art history. Stuttgart 1956.

- Gottlieb Weitbrecht : The celebration of the 400th anniversary of the Hospital Church in Stuttgart on the Reformation Festival Sunday November 5, 1893. Stuttgart [approx. 1893].

New hospital courtyard

Basic literature : #Bachmann 2014 , #Bartetzko 2014 , #Jaeger 2014 , #Lederer 2014.1 , #Sayah 2014 .

Photos, plans: #Bachmann 2014 , #Holl 2014 , #MG 2014 , #Renninger 2014 .

- Eye candy . In: AIT. Architecture, interior design, technical expansion 2014, issue 5, pages 12–13.

- In a new guise. Medieval and modern. In: German Architektenblatt Volume 46, 2014, No. 4, page 8, online: .

- Wolfgang Bachmann: Administration building of the Evangelical Church in Stuttgart. In: Bauwelt issue 25 from July 4, 2014, pages 15–23.

- Dieter Bartetzko: What you can learn in Stuttgart. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung number 144 from June 25, 2014, page 13.

- Hospitalhof Stuttgart. LRO build church education center. In: BauNetz from March 1, 2012, online: (with 6 images of design drawings).

- Thomas Borgmann: Dispute over trees at the hospital courtyard. In: Stuttgart-Zeitung.de of 10 December 2010 online: .

- Thomas Faltin: A font from the forest. In: Stuttgarter Zeitung number 211 of September 12, 2014, page 21.

- Achim Geissinger: Stuttgart. Protestant education center Hospitalhof . In: db Deutsche Bauzeitung Volume 148, 2014, Issue 7–8, page 65.

- (gös): Hospital church receives historical baptismal font back. In: Stuttgarter Nachrichten number 229 of October 4, 2014, page 22.

- Nicole Höfle: Hospital Church Stuttgart. Webcam on the hospital church. In: Stuttgart-Zeitung.de of 28 February 2012 online: .

- Nicole Höfle: Interview [with Monika Renninger] about the Hospitalhof in Stuttgart. “You know where you are even without a cross”. In: Stuttgart Zeitung.de of 24 April 2014 online: .

- Nicole Höfle: The new Hospitalhof breathes history. In: Stuttgarter Zeitung number 83 of April 9, 2014, page 23.

- Christian Holl: Formal, Functional, Friendly. Hospitalhof in Stuttgart by Lederer Ragnarsdóttir Oei. Stuttgart 2014, online: .

- in No. 62 of April 2014. Online: .

- Falk Jaeger : The answer is amazing. The new hospital courtyard brings back memories of the former Dominican monastery. In: Stuttgarter Nachrichten No. 108 of May 12, 2014, page 13, online (with a different heading): [7] .

- Arno Lederer ; Jórunn Ragnarsdóttir ; Marc Oei: Lederer Ragnarsdóttir Oei 1 Berlin 2012.

- Arno Lederer : new hospital courtyard building. In: #Renninger 2014 , pages 4–7.

- Arno Lederer : Presentation boards for the exhibition for the opening of the Hospitalhof in spring 2014. Stuttgart 2014.

- (MG): Hospitalhof in Stuttgart. In: Detail. Zeitschrift für Architektur + Baudetail 2014, issue 7/8, pages 739–745, 829.

- (oss): Hospital district. Compromise in the dispute over trees. In: Stuttgarter Zeitung of 10 February 2011 Page 22, online: .

- Monika Renninger (editor); Rolf Ahlrichs (editor): The new hospital courtyard. Stuttgart 2014.

- Amber Sayah: The new hospital courtyard. House with memory . In: Stuttgarter-Zeitung.de of 16 April 2014 online: .

- Christoph Schweizer: Festival week ended, education started. Stuttgart 2014, online: .

media

- New Hospitalhof Stuttgart (video). Stuttgart 2014, production: Architektur und Medien Klaus F. Linscheid, speakers: Arno Lederer and Jórunn Ragnarsdóttir , running time: 2:31 minutes, online:

- Katja Schalla: Building for the Church - Lederer Architects, Ragnarsdóttir, Oei | SWR Kunscht! (Video) Stuttgart 2014, production: SWR , camera: Jacqueline Appel, editor: Holger Schwämmle, running time: 4:26 minutes, online:

Web links

- Website of the Hospitalhof Stuttgart

- Hospitalhof on the website of Lederer Ragnarsdóttir Oei: [8]

- Literature list for the hospital yard by Lederer Ragnarsdóttir Oei

Footnotes

- ↑ Laura Köhlmann in #In 2014 , page 10.

- ↑ #Renninger 2014 , page 44.

- ↑ New familiarity - building trade. Retrieved June 18, 2018 .

- ↑ # In 2014 , page 2.

- ↑ #Renninger 2014 , page 44.

- ↑ #Renninger 2014 , page 47.

- ↑ Hospitalhof website, About us .

- ↑ Website of the Evangelical Church in Stuttgart: Archived copy ( memento of the original from December 22, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. .

- ↑ #Renninger 2014 , pp. 44–46.

- ↑ Press release from the Evangelical Church in Württemberg from October 4, 2010: [1] ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ # In 2014 , page 12.

- ↑ # In 2014 , page 12.

- ^ Website of the Stuttgart Hospice: [2] .

- ^ Website of the Church in the City: [3] .

- ^ Website of Helmut A. Müller: [4] .

- ↑ #Renninger 2014 , page 44.

- ↑ #Strecker 1993 , S. 143rd

- ↑ “The architect Roland Ostertag , who has been campaigning for a liveable Stuttgart for decades, even speaks of a“ demolition fury ”that is more raging in Stuttgart than in other cities. Here the “will and the knowledge” is not there to maintain the old or to integrate it into the new. “All people long to live in an environment that speaks to them. That is lost if you tear off the old layers, "says Ostertag." (Thomas Faltin: Monument protection in Stuttgart. The city's historical legacy is fading. In: Stuttgarter Zeitung.de of March 19, 2012, online:. )

- ^ Thomas Faltin: Monument protection. Wengerterhaus is being demolished. In: Stuttgart Zeitung.de of 21 June 2012 online: .

- ↑ The number of buildings was estimated based on the number of house numbers.

- ↑ #Bartetzko 2014 .

- ^ Annette Schmidt: Ludwig Eisenlohr. An architectural path from historicism to modernity. Stuttgart architecture around 1900. Stuttgart-Hohenheim 2006, pages 501–502.

- ↑ #Borgmann 2010 , #In 2014 , page 2, #oss 2011 .

- ↑ “The inhospitableness of our cities” is the title of a book by Alexander Mitscherlich , which is used in #Lederer 2012 , page 8, for the general unease about architecture in the seventies.

- ↑ #Lederer 2012 , page 9.

- ↑ #Lederer 2014.1 , page 2.

- ↑ #Lederer 2014.1 , page 2, #In 2014 , page 3.

- ↑ # Bachmann 2014 , page 15.

- ↑ #Lederer 2014.1 , page 7.

- ↑ #Nerdinger 2001 , page 6, 18-20.

- ↑ #Lederer 2014.1 , page 7.

- ↑ #Renninger 2014 , page 47.

- ↑ #Lederer 2014.1 , page 7.

- ↑ For floor plan and capacity see: [5] .

- ↑ #Bartetzko 2014 .

- ↑ # Jaeger 2014 .

- ↑ #Renninger 2014 , page 46.

- ↑ # In 2014 , page 2.

- ↑ # Jaeger 2014 .

- ↑ Examples of the use of triangular windows in LRO buildings: Schule im Park, Ostfildern (2002), Heilbronn vocational school (2003), Baden-Württemberg Cooperative State University Lörrach (2008), Karlsruhe residential, office and commercial building (2013), Bischöfliches Ordinariat Rottenburg (2013). - Images: LRO, projects , school in the park: school in the park, triangular window .

- ↑ At the Schreieschesch-Schule in Friedrichshafen , the straight-fitting, blue-colored brims are designed like a director's umbrella.

- ↑ # In 2014 , page 7.

- ↑ Illustrations with the baptismal font: #Wais 1956 , page 1, plates 55, 57, 59, 65.

- ↑ For the location of the Bannwald Mietholz see the blog paths in the Stuttgart region .

- ↑ # Faltin 2014 , # gös 2014 .

- ↑ The easting of the church suggested by Hansmartin Decker-Hauff and others is not convincing, as the church choir is oriented to the northeast and not strictly to the east.

- ↑ #Lederer 2014.1 , page 6.

- ↑ # Decker-Hauff 1966 , page 281.

- ↑ Based on a sketch by Rudolf Lempp ( #Hospitalkirche 1960 , page 27).

- ↑ Based on the ground floor plan of the New Hospitalhof ( #Renninger 2014 , page 18).

- ↑ #Sauer 1993.1 , pages 11, 14, 24, #Wais 1951.1 , page 70, no. 51, #Wais 1956 , page 50, no. 52.

- ↑ #Wais 1956 , pp. 42, 46-47.

- ↑ #Wais 1954.2 , page 82.

- ↑ #Sauer 2003 .

- ^ #Wais 1956 , page 62.

- ↑ #Swiss 2014 .

- ↑ #Wais 1954.1 , page 90.

- ^ Website of the Evangelical Church in Stuttgart: [6] .

- ↑ #Sauer 2003 .

- ↑ #Hospitalkirche 1960 , page 11, #Sauer 1993.1 , page 71.

- ↑ #Wais 1954.1 , page 90.

- ↑ #Hospitalkirche 1960 , page 10, # Möhring 1984 , page 4.

- ↑ #Hospital Church 1960 , page 15.

- ↑ #Sayah 2014 .

- ↑ The article was published shortly before Easter 2014.

- ↑ # Jaeger 2014 .

- ↑ # Bachmann 2014 , pp. 16-17.

- ↑ #Bartetzko 2014 .

- ↑ # In 2014 , page 13.

Coordinates: 48 ° 46 ′ 40 ″ N , 9 ° 10 ′ 22 ″ E