Feline arterial thromboembolism

The feline arterial thromboembolism ( FATE Syndrome ) is a disease of domestic cats , in which blood clots ( thrombi ) arteries ( arteries clog) and thus a severe circulatory disorder cause. In relation to the total number of cat patients, the disease is rare, but relatively common in cats with heart disease : around a sixth of cats with heart disease are affected. Heart disease is the leading cause of arterial thromboembolism. It causes blood clots to form in the heart, which leave with the bloodstream and become larger blood vesselsembarrassed, in cats especially the aorta at the exit of the two outer pelvic arteries . Arterial thromboembolism occurs suddenly and is very painful. The relocation of the end section of the aorta results in an undersupply of blood in the hind legs. The result is paralysis, cold hind limbs and later severe tissue damage. Other blood vessels are rarely affected; the symptoms of failure then depend on the supply area of the affected artery. Since the drug dissolution of the blood clot in cats does not achieve satisfactory results, the self-dissolution of the clot through the body's own repair processes is nowadays relied on. In addition, pain therapy and coagulation prophylaxis are carried out and the underlying disease is treated. The mortality rate from arterial thromboembolism in cats is very high. 50 to 60% of the affected animals are euthanized without attempting treatment and only a quarter to a third of the animals survive such an event. In about half of the recovered cats, a new thromboembolism develops despite coagulation prophylaxis.

Occurrence, cause and development of the disease

| Underlying disease | frequency |

|---|---|

| hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | 52% |

| other cardiomyopathy | 17% |

| Hyperthyroidism | 9% |

| tumor | 5% |

Feline arterial thromboembolism is a rare disease, accounting for 0.1–0.3% of the total number of cat patients. The mean age at the onset of thromboembolism is 12 years (1 to 21 years).

The FATE syndrome arises in around 70% of cases as a result of heart disease, usually a heart disease with thickening of the heart wall ( hypertrophic cardiomyopathy , HCM). Up to 17% of cats with HCM will develop arterial thromboembolism, but cats with other cardiomyopathies are also at increased risk. Another risk group are cats with abnormally increased blood coagulation , which can occur with hyperthyroidism , tumors , extensive inflammation , blood poisoning (sepsis), injuries or blood clotting within the blood vessels . Male cats are more prone to illness , which is related to the higher incidence of heart disease in male cats .

The damage to the inner lining of the heart and the slowing down of blood flow in the enlarged left auricle and auricle are responsible for the formation of blood clots ( thrombi ) . The tissue damage leads to the release of tissue factor and the activation of coagulation factors . The intact glycocalyx of the endothelial cells of the inner lining of the heart normally reduces contact with blood cells and macromolecules . If endothelial cell damage occurs, more reactive oxygen species (ROS), nitrogen monoxide (NO), matrix metalloproteases and inflammation- promoting cytokines are formed and cell adhesion molecules are upregulated . The damage to the endothelial cells exposes the underlying extracellular matrix , to which platelets attach and form a clot. The clot consists of blood platelets that are connected to one another by the clotting protein fibrin . As the clot matures, the proportion of fibrin increases and the clot may become stratified. In healthy animals, too, injuries to the endothelium occur spontaneously, but there is a balanced relationship between thrombus formation and breakdown. Substances such as antithrombin III , thrombomodulin , tissue-specific plasminogen activator and urokinase dissolve blood clots and prostacyclin and nitric oxide inhibit the agglomeration of blood platelets. The conservative treatment of arterial thromboembolism in cats is based on this endogenous dissolution of the clot (see below).

In cats, blood clots mainly develop in the left atrial appendage . They or parts of them are carried away with the blood stream, reach the aorta via the left ventricle, get stuck in vascular outlets and block them. This condition is known as thromboembolism or thromboembolism. In cats, this occurs predominantly in the aorta in the area of its terminal branch, i.e. at the exit of the two outer pelvic arteries ( aa. Iliacae externae ). This is also known as a "saddle thrombus" or "riding thrombus". This leads to an insufficient supply of blood to the rear extremities. In addition, the blood platelets release thromboxane and serotonin , which lead to a narrowing of the blood vessels and thus to a reduced blood flow to blood vessels that are not directly affected . Serotonin also stimulates pain fibers , which contributes to the high painfulness of the disease. Only in 10% of cases are other blood vessels affected, for example the upper arm artery , the pulmonary arteries , cerebral vessels , intestinal vessels or coronary arteries .

In humans, heart disease (especially atrial fibrillation ), increased blood clotting and atherosclerosis are the most common underlying diseases for the development of arterial thromboembolism . Here, too, the thrombi arise mainly in the left side of the heart. Most often, the cerebral arteries ( stroke ) and the arteries of the leg ( acute arterial occlusion of the extremities , acute lower limb ischemia ) are obstructed . Thromboembolism of the vessels of the arm, the upper mesenteric artery or the renal arteries ( kidney infarction ) is less common . Leriche syndrome (aortic bifurcation syndrome), which corresponds to the most common localization in cats, is extremely rare in humans. Arterial thromboembolism occurs much less frequently in domestic dogs than in cats; common underlying diseases in dogs are diseases of the immune system, tumors, sepsis, heart diseases, protein loss enteropathy , protein loss nephropathy and high blood pressure . Aortic thromboses also occasionally occur in dogs, but here the thrombi arise directly at the branching of the aorta; as a thromboembolic event like in cats, they are extremely rare. There are also individual case reports of thromboembolism in domestic horses, while they are of no practical importance in other animal species. In the laboratory animals used in human stroke research, thrombi are artificially generated.

Symptoms, clinical diagnosis and laboratory findings

The disease occurs suddenly (peracute) and is accompanied by severe pain. Affected cats scream ("vocalize") and often have low temperature . The extent of the further symptoms depends on the location of the clot and on whether the vessel is completely or only partially obstructed. Closure of the pelvic arteries leads to partial ( paresis ) or complete paralysis ( plegia ) of the hind extremities. In most cases, both hind legs are affected. The muscles are hardened and painful after about 10 hours, especially the lower leg muscles. The pulse at the femoral artery ( arteria femoralis ) is markedly reduced or absent in 78% of cases completely. The paws are cold and the area of the claws and pads in particular often shows bluish discoloration ( cyanosis ) or is noticeably pale. The reflexes of the hind limbs ( patellar tendon reflex , tibialis-cranialis reflex and flexor reflex ) are greatly reduced or completely absent . Frequently there is an increase in the respiratory rate, dyspnoea and syncope . Loss of perception can also occur. The main symptoms can be in the "5-P Rule" - paresis (paralysis), pallor (paleness), Pain (pain), Pulselessness (pulse loss) Poikilothermia summarize - (low temperature). The tail muscles , the anal reflex and the bladder function are mostly not affected.

Other occlusions are much rarer and the clinical picture depends on the part of the body or organ affected. Upper arm artery occlusion occurs predominantly on the right and causes sudden paralysis of the forelegs. The thromboembolism of blood vessels in the lungs manifests itself in an increased respiratory rate and shortness of breath . The clinical picture of the occlusion of cerebral vessels ( ischemic stroke ) depends heavily on the affected vessel and thus on the damaged brain area. Mostly there are one-sided neurological deficits. The occlusion of a coronary artery ( myocardial infarction ) leads to cardiac arrhythmias with mostly fatal outcome and is therefore often no longer referred to a vet, so that its frequency is possibly underestimated. The occlusion of kidney or intestinal vessels causes severe abdominal pain ( acute abdomen ) and often leads to rapid death as well. There are also case reports of the simultaneous occlusion of several vessels with paralysis of all limbs or of the cerebellum and kidneys with severe imbalance.

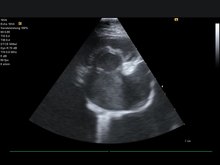

Listening to the heart ( auscultation ) usually reveals heart murmurs , an irregular heartbeat , palpitations , extrasystoles and a "gallop rhythm" - a sequence of heart sounds reminiscent of a galloping horse. Up to two-thirds of FATE patients are in congestive heart failure, in which the heart no longer pumps enough blood to the body. A means of ECG detectable atrial fibrillation represents an additional risk factor. The Aortenthrombus can often directly sonographically be represented, where appropriate, also can angiography or electromyography be performed. By means of echocardiography , thrombi and their preliminary stages in the heart can be made visible and the functional state of the heart can be assessed. The loss of pulse in the femoral artery can also be detected by means of Doppler sonography , whereby it should be noted that the pulse can still be detected sonographically in the event of an incomplete vascular occlusion. Using infrared thermography , temperature differences between the fore and hind limbs can be objectified. The sensitivity of this method is between 80 and 90%, the specificity 100%. A thromboembolism of the lungs often goes undetected; an X-ray examination of the chest can provide initial clues here, and a reliable diagnosis can be made using computed tomography or scintigraphy of the lungs. Magnetic resonance imaging is indicated if a stroke is suspected .

The activities of the enzymes creatine kinase (CK) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) are increased due to the death of muscle cells in the blood. If there is a heart disease, which is often the case, the NTproBNP is above the normal range . The "kidney values" ( creatinine , urea , SDMA ) can also be increased due to the shock-related reduced kidney function (prerenal azotemia ). However, all laboratory values are not specific for arterial thromboembolism and only play a subordinate role in confirming the diagnosis. It can be helpful to determine the blood sugar or lactate concentration in the body compared to that in the paralyzed limb. The determination of the thyroxine concentration (T4) in the blood is useful for detecting an overactive thyroid ; in 1.7% of cats with thromboembolism, the overactive thyroid was not previously known.

Diagnosis and differential diagnosis

In the most common localization (aortic thrombosis), the diagnosis can usually already be made on the basis of the preliminary report and the clinical symptoms (peracute afterhand paralysis without trauma ). An existing heart disease provides further evidence, but only about 15% of cats with thromboembolism are already aware of the heart disease.

The other more common ischemic myopathy , the tilt window syndrome , can usually be ruled out by asking the animal owner. In addition, the tilt window syndrome is not associated with severe pain. In terms of differential diagnosis , trauma to the spinal cord (traffic accident, falling window), which can be traced back to an event that the owner may not have observed, must also be excluded. A herniated disc or a spinal cord infarction can also lead to sudden symptoms of paralysis. Also, tumors in the spinal cord or spinal canal can trigger Nachhandlähmungen, but these evolve mostly slow and the failure symptoms appear gradually.

The diagnosis of vascular occlusions of the internal organs is more difficult, here special examinations ( CT , MRT ) are necessary to confirm the diagnosis, which are only available in larger facilities.

therapy

The treatment of arterial thromboembolism in cats consists of pain therapy, the prevention of further clots and, if necessary, the treatment of insufficient heart function . Intensive care care is usually required for three days before home treatment can be continued.

To reduce the pain, the administration of highly effective painkillers is indicated, with opioid analgesics such as levomethadone or fentanyl being the most effective. However, both active ingredients are not approved for cats in the EU and must therefore be rededicated in the interests of a therapy emergency . In addition, fentanyl only works for about 30 minutes and levomethadone for about 5 hours if data for the dog are used as a basis, which limits further treatment at home. A permanent drip infusion with the combination of fentanyl and lidocaine has been described. In addition to its analgesic effect, lidocaine also protects to a certain extent against damage caused by the reopening of the blocked vessel ( reperfusion damage ). However, the therapeutic range of lidocaine in cats is very narrow , as low as 6 mg / kg can be fatal. The only opioid analgesic approved for cats, buprenorphine , does not have a sufficient analgesic effect for initial treatment, at least not when both external pelvic arteries are completely occluded. It can be used for further treatment at home, especially since it can easily be administered through the oral mucosa and has a duration of action of around 8 hours. Non-opioid analgesics do not provide adequate pain reduction and can increase circulatory disorders in animals and thus cause kidney or gastrointestinal damage. Only metamizole is suitable for later further treatment.

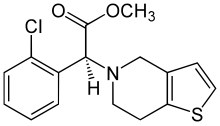

Inhibiting the formation of further blood clots - thrombosis prophylaxis - is the second important pillar of FATE treatment. It should be done as early as possible. For this purpose, agents to inhibit blood coagulation, such as low molecular weight heparins , are used in parallel, while agents to prevent the agglomeration of blood platelets ( thrombocyte aggregation ) such as ASA and clopidogrel are used. For long-term prophylaxis, clopidogrel is preferably given, as it significantly increases the survival time compared to ASA. The use of the active ingredient rivaroxaban as another effective drug is also being discussed.

Cats in congestive heart failure are given additional oxygen to compensate for the oxygen deficiency . High doses of furosemide are used to reduce preload and afterload and thus relieve the heart . In the case of heart disease with dilation of the ventricle ( DCM ) or heart disease with cardiac wall thickening ( HCM ) in an advanced stage, pimobendan can be used to improve pumping performance, possibly also with dobutamine . Pimobendan also slightly increases blood flow in the left atrium and atrial appendage and also improves atrial function. If, on the other hand, there is no congestive heart failure, but reduced blood flow (perfusion), then full electrolyte solutions are infused . In the case of an underlying hyperthyroidism, anti- thyroid drugs such as thiamazole or carbimazole are administered.

The benefit of external heat supply in cats with hypothermia is controversial. Often the front part of the body is at a normal temperature and the low temperature only affects the rear part and thus also the rectum , where the body temperature is usually measured in cats. The measurement in the armpit area or in the ear is unreliable. However, the comparison between armpit and rectal temperature provides at least information to differentiate between local and general under-temperature. In the latter case, a supply of heat is indicated.

The obvious treatment, the reopening of the vessel by drug dissolution ( thrombolysis ) or invasive removal of the clot ( thrombectomy ), as it has long been established in human medicine for occlusive diseases such as stroke or heart attack , gives unsatisfactory results in cats and is therefore no longer recommended. Thrombolysis with streptokinase , urokinase or tissue-specific plasminogen activator has not improved the success of the treatment in various studies . These often lead to fatal reperfusion disorders , hyperkalemia , metabolic acidosis , kidney failure and bleeding, so that the survival rate is often lower than with conservative treatment. In human medicine, such treatments are only carried out in highly specialized facilities ( heart centers , stroke units ) with high expenditure on personnel and equipment. Surgical removal of the thrombus is also rarely performed in veterinary medicine because of the risks involved, although it can be successful in individual cases. It is associated with the same complications as thrombolysis and is therefore no longer recommended. Therefore, the body's own dissolution of the clot and thus spontaneous recanalization , which occurs quickly enough in almost 40% of cases , is currently used .

Prognosis and prevention

The treatment prospects ( prognosis ) for thromboembolism of the aorta are uncertain or poor. According to a US study, only about a third of cats survive arterial thromboembolism, with half of those who die are euthanized without attempting treatment . In a UK study, around 60% of patients were euthanized. Only 27% of the animals survived the first 24 hours. The mean survival time was 94 days, after one year only 2% of the animals were still alive.

The prognosis depends largely on the extent and duration of the damage, with complete occlusions of the pelvic arteries on both sides showing the lowest chance of survival. If only one limb is affected and there is residual motor function, the chances that the cat will recover and continue to live with a good quality of life are better. If the internal body temperature is above 37.2 ° C - the normal temperature for house cats is around 39 ° C - the prospect of treatment is better than if the temperature is more severe. An excess of potassium in the blood ( hyperkalaemia ) and elevated kidney values ( azotemia ) are further negative prognostic factors. Even after a spontaneous reopening of the blood vessel ( recanalization ), recurrences often occur due to renewed thromboembolism, which even thrombosis prophylaxis cannot reliably prevent. Thromboembolism recurs in half of patients despite treatment with clopidogrel. In addition, the extent of the heart disease, in particular the extent of the atrial enlargement and the pumping capacity of the left ventricle, determine the further survival of the patient.

In contrast, if smaller cerebral arteries are occluded, the prognosis is favorable. Often there is a reduction in the symptoms of failure within two to three weeks, as other brain areas take over the function of the infarct area. The occlusion of the humerus artery also has a good chance of healing. The prognosis and mortality of pulmonary thromboembolism is unknown as it is very rare. Individual reports show that cats can survive such an event and that lung function can return to normal through the formation of collaterals . Other occlusions (intestinal, kidney and coronary arteries) are very often fatal.

Some small animals - cardiologists recommend clotting prophylaxis even at certain changes in the heart, before the occurrence of thromboembolism. A study was able to show that a flow velocity in the left atrial appendage of less than 0.2 m / s is related to the occurrence of thrombi and spontaneous echocardiographic contrast (“ smoke ”). Spontaneous echocardiographic contrast is an agglomeration of red blood cells and thus a pre-thrombus stage that is reminiscent of billows of smoke in the sonographic representation. Prospective studies to prove the effectiveness of such a treatment are still pending.

literature

- Domink Faissler et al .: Ischemic Myopathy . In: Andre Jaggy (Ed.): Atlas and textbook of small animal neurology . Schlütersche, Hannover 2005, ISBN 3-87706-739-5 , p. 272-273 .

- Florian Sänger and Rene Dörfelt: Feline arterial thromboembolism - current status of diagnostics and therapy. In: Kleintierpraxis Volume 65, Number 4, April 2020, pp. 220-235. doi: 10.2377 / 0023-2076-65-220

- Lisa Joy Miriam Keller: Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy in the Cat . In: Markus Killich (Ed.): Small animal cardiology. Georg Thieme, Stuttgart 2019, ISBN 978-3-13-219991-0 , p. 369-370 .

- Alan Kovacevic: Cardiac Emergencies . In: Nadja Siegrist (Ed.): Emergency medicine for dogs and cats . Enke, Stuttgart 2017, ISBN 978-3-13-205281-9 , pp. 231-255 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Stephanie A. Smith et al .: Arterial thromboembolism in cats: acute crisis in 127 cases (1992-2001) and long-term management with low-dose aspirin in 24 cases . In: J Vet Intern Med Volume 17, Number 1, 2003, pp. 73-83.

- ↑ DF Hogan, BM Brainard: Cardiogenic embolism in the cat. In: Journal of veterinary cardiology: the official journal of the European Society of Veterinary Cardiology. Volume 17 Suppl 1, December 2015, pp. S202-S214, doi: 10.1016 / j.jvc.2015.10.006 , PMID 26776579 (review).

- ↑ a b c d e f g Kieran Borgeat et al .: Arterial thromboembolism in 250 cats in general practice: 2004-2012. In: Journal of veterinary internal medicine. Volume 28, number 1, 2014 Jan-Feb, pp. 102-108, doi : 10.1111 / jvim.12249 , PMID 24237457 , PMC 4895537 (free full text).

- ↑ Florian Sänger and Rene Dörfelt: Feline arterial thromboembolism - current status of diagnostics and therapy. In: Kleintierpraxis Volume 65, number 4, 2020, p. 220. doi: 10.2377 / 0023-2076-65-220

- ↑ a b Florian Sänger and Rene Dörfelt: Feline arterial thromboembolism - current status of diagnostics and therapy. In: Kleintierpraxis Volume 65, number 4, 2020, p. 222. doi: 10.2377 / 0023-2076-65-220

- ↑ T. Dehghani and A. Panitch: Endothelial cells, neutrophils and platelets: getting to the bottom of an inflammatory triangle. In: Open biology. Volume 10, number 10, 2020, p. 200161, doi: 10.1098 / rsob.200161 , PMID 33050789 , PMC 7653352 (free full text).

- ↑ a b c d Laurent Loquet et al .: Feline arterial thromboembolism: prognostic factors and treatment. In: Vlaams Tiergeneeskundig Tijdschrift Volume 87, 2018, pp. 164–175

- ↑ a b S. L. Kochie et al .: Effects of pimobendan on left atrial transport function in cats. In: Journal of veterinary internal medicine. Volume 35, number 1, January 2021, pp. 10-21, doi : 10.1111 / jvim.15976 , PMID 33241877 , PMC 7848333 (free full text).

- ↑ a b c d Florian Sänger and Rene Dörfelt: Feline arterial thromboembolism - current status of diagnostics and therapy. In: Kleintierpraxis Volume 65, Number 4, 2020, p. 224. doi: 10.2377 / 0023-2076-65-220

- ↑ a b Andreas Kirsch: Aortic thrombosis in cats. In: veterinärspiegel 2 (2008), pp. 84-90.

- ↑ a b c Clarke Atkins: Systemic Arterial Embolism in Cats. In: World Small Animal Veterinary Association World Congress Proceedings, 2007 ( online )

- ↑ MR Lyaker et al .: Arterial embolism. In: International journal of critical illness and injury science. Volume 3, number 1, January 2013, pp. 77-87, doi : 10.4103 / 2229-5151.109429 , PMID 23724391 , PMC 3665125 (free full text).

- ↑ BK Chong and JB Kim: Successful surgical treatment for thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm with leriche syndrome. In: The Korean journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. Volume 48, number 2, April 2015, pp. 134-138, doi : 10.5090 / kjtcs.2015.48.2.134 , PMID 25883898 , PMC 4398158 (free full text).

- ↑ K. Gardiner: Aortic thromboembolism in a basset hound-beagle crossbred dog with protein-losing nephropathy. In: The Canadian veterinary journal = La revue veterinaire canadienne. Volume 61, number 3, 03 2020, pp. 309-311, PMID 32165756 , PMC 7020641 (free full text).

- ↑ RL Winter et al .: Aortic thrombosis in dogs: presentation, therapy, and outcome in 26 cases. In: Journal of veterinary cardiology: the official journal of the European Society of Veterinary Cardiology. Volume 14, Number 2, 2012, pp. 333-342, doi : 10.1016 / j.jvc.2012.02.008 , PMID 22591640 .

- ^ MW Ross et al .: First-pass radionuclide angiography in the diagnosis of aortoiliac thromboembolism in a horse. In: Veterinary radiology & ultrasound: the official journal of the American College of Veterinary Radiology and the International Veterinary Radiology Association. Volume 38, Number 3, 1997 May-Jun, pp. 226-230, doi : 10.1111 / j.1740-8261.1997.tb00845.x , PMID 9238795 .

- ^ Andre Jaggy: Atlas and textbook of small animal neurology. Schlütersche 2005, ISBN 3-87706-739-5 , p. 272.

- ^ Marwa H. Hassan et al .: Feline aortic thromboembolism: Presentation, diagnosis, and treatment outcomes of 15 cats . In: Open Vet J. Volume 10, Number 3, 2020, pp. 340–346. PMID 33282706 , PMC 7703610 (free full text), doi: 10.4314 / ovj.v10i3.13

- ↑ Wendy A. Ware: Systemic arterial thromboembolism in cats . In: Richard W. Nelson and C. Guillermo Couto (Eds.): Small Animal Internal Medicine . 4th edition. Elsevier Health Sciences, 2008, ISBN 978-0-323-06512-2 , pp. 194-200 .

- ^ A b c R. Hylands: Pulmonary thromboembolism. In: The Canadian veterinary journal = La revue veterinaire canadienne. Volume 47, Number 4, April 2006, pp. 385-6, 388, PMID 16642881 , PMC 2828335 (free full text).

- ↑ a b L. S. Garosi: Cerebrovascular disease in dogs and cats. In: The Veterinary clinics of North America. Small animal practice. Volume 40, Number 1, January 2010, pp. 65-79, doi : 10.1016 / j.cvsm.2009.09.001 , PMID 19942057 (review).

- ^ A b Pru Galloway: Feline Aortic Thromboembolism. In: Proc of the Companion Animal Society of the NZVA . FCE Pub No 214, 2001.

- ^ DB Bowles et al .: Cardiogenic arterial thromboembolism causing non-ambulatory tetraparesis in a cat. In: Journal of feline medicine and surgery. Volume 12, Number 2, February 2010, pp. 144-150, doi : 10.1016 / j.jfms.2009.06.004 , PMID 19692276 .

- ↑ GB Cherubini, C. Rusbridge, BP Singh, S. Schoeniger, P. Mahoney: Rostral cerebellar arterial infarct in two cats. In: Journal of feline medicine and surgery. Volume 9, Number 3, June 2007, pp. 246-253, doi : 10.1016 / j.jfms.2006.12.003 , PMID 17317258 .

- ^ Alan Kovacevic: Cardiological Emergencies . In: Nadja Siegrist (Ed.): Emergency medicine for dogs and cats . Enke, Stuttgart 2017, ISBN 978-3-13-205281-9 , pp. 231-255 .

- ^ SA Smith, AH Tobias: Feline arterial thromboembolism: an update. In: The Veterinary clinics of North America. Small animal practice. Volume 34, Number 5, September 2004, pp. 1245-1271, doi: 10.1016 / j.cvsm.2004.05.006 , PMID 15325481 (review).

- ↑ C. Pouzot-Nevoret et al .: Infrared thermography: a rapid and accurate technique to detect feline aortic thromboembolism. In: Journal of feline medicine and surgery. Volume 20, number 8, 08 2018, pp. 780–785, doi: 10.1177 / 1098612X17732485 , PMID 28948905 .

- ↑ JL Pouchelon et al .: Diagnosis of pulmonary thromboembolism in a cat using echocardiography and pulmonary scintigraphy. In: The Journal of Small Animal Practice. Volume 38, Number 7, July 1997, pp. 306-310, doi : 10.1111 / j.1748-5827.1997.tb03472.x , PMID 9239634 .

- ^ JL Ward et al .: Evaluation of point-of-care thoracic ultrasound and NT-proBNP for the diagnosis of congestive heart failure in cats with respiratory distress. In: Journal of veterinary internal medicine. Volume 32, number 5, September 2018, pp. 1530-1540, doi: 10.1111 / jvim.15246 , PMID 30216579 , PMC 6189386 (free full text).

- ↑ Florian Sänger and Rene Dörfelt: Feline arterial thromboembolism - current status of diagnostics and therapy. In: Kleintierpraxis Volume 65, Number 4, 2020, p. 226. doi: 10.2377 / 0023-2076-65-220

- ↑ a b c d e Virginia Luis Fuentes: Arterial thromboembolism: risks, realities and a rational first-line approach. In: Journal of feline medicine and surgery. Volume 14, Number 7, July 2012, pp. 459-470, doi : 10.1177 / 1098612X12451547 , PMID 22736680 (review).

- ^ A b Daniel F. Hogan et al .: Secondary prevention of cardiogenic arterial thromboembolism in the cat: The double-blind, randomized, positive-controlled feline arterial thromboembolism; clopidogrel vs. aspirin trial (FAT CAT). In: J Vet Cardiol Volume 17, Suppl. 1, Dec. 2015, pp. 306-317, doi : 10.1016 / j.jvc.2015.10.004 , PMID 26776588

- ↑ Feline arterial thromboembolism . In: Jan-Gerd Kresken, Ralph T. Wendt, Peter Modler (ed.): Practice of cardiology dog and cat . Thieme, Stuttgart 2019, ISBN 978-3-13-242994-9 , pp. 389-392 .

- ↑ Florian Sänger and Rene Dörfelt: Feline arterial thromboembolism - current status of diagnostics and therapy. In: Kleintierpraxis Volume 65, number 4, 2020, p. 232. doi: 10.2377 / 0023-2076-65-220

- ↑ Wolfgang Löscher: Fully synthetic morphine derivatives . In: Wolfgang Löscher, Fritz Rupert Ungemach and Reinhard Kroker (eds.): Pharmacotherapy for pets and farm animals . 7th edition. Paul Parey, Berlin 2006, ISBN 978-3-8304-4160-1 , pp. 95-96 .

- ^ TQ O'Brien, SC Clark-Price, EE Evans, R. Di Fazio, MA McMichael: Infusion of a lipid emulsion to treat lidocaine intoxication in a cat. In: Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. Volume 237, Number 12, December 2010, pp. 1455-1458, doi: 10.2460 / javma.237.12.1455 , PMID 21155686 .

- ↑ Florian Sänger and Rene Dörfelt: Feline arterial thromboembolism - current status of diagnostics and therapy. In: Kleintierpraxis Volume 65, Number 4, 2020, p. 228. doi: 10.2377 / 0023-2076-65-220

- ^ A b Sonja Fontara: Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in cats. In: Kleintierpraxis , Volume 61, Number 10, 2016, pp. 560-578.

- ↑ Alan Kovacevic: Feline aortic thrombosis - does prophylaxis make sense? In: kleintier specifically 2014, volume 17, number 3, pp. 22–26. doi: 10.1055 / s-0033-1361537

- ↑ https://vet.uga.edu/vet-med-offers-clinical-trial-for-cats-with-history-of-arterial-thromb/

- ↑ a b Florian Sänger and Rene Dörfelt: Feline arterial thromboembolism - current status of diagnostics and therapy. In: Kleintierpraxis Volume 65, Number 4, 2020, p. 229. doi: 10.2377 / 0023-2076-65-220

- ^ ME Peterson and DP Aucoin: Comparison of disposition of carbimazole and methimazole in clinically normal cats. In: Res. Vet. Sci. Volume 54, Number 3, 1993, pp. 351-355, PMID 8337482 .

- ↑ Victoria A Smith et al .: Comparison of axillary, tympanic membrane and rectal temperature measurement in cats . In: J Feline Med Surg , Volume 17, Number 12, 2015, pp. 1028-1034. PMID 25600082 doi: 10.1177 / 1098612X14567550

- ↑ Florian Sänger and Rene Dörfelt: Feline arterial thromboembolism - current status of diagnostics and therapy. In: Kleintierpraxis Volume 65, Number 4, 2020, p. 230. doi: 10.2377 / 0023-2076-65-220

- ↑ a b c S. B. Reimer et al .: Use of rheolytic thrombectomy in the treatment of feline distal aortic thromboembolism. In: Journal of veterinary internal medicine. Volume 20, Number 2, 2006 Mar-Apr, pp. 290-296, doi : 10.1892 / 0891-6640 (2006) 20 [290: uortit] 2.0.co; 2 , PMID 16594585 .

- ↑ J. Guillaumin et al .: Thrombolysis with tissue plasminogen activator (TPA) in feline acute aortic thromboembolism: a retrospective study of 16 cases. In: Journal of feline medicine and surgery. Volume 21, number 4, 04 2019, pp. 340–346, doi: 10.1177 / 1098612X18778157 , PMID 29807505 .

- ↑ T. Vezzosi et al .: Surgical embolectomy in a cat with cardiogenic aortic thromboembolism. In: Journal of veterinary cardiology: the official journal of the European Society of Veterinary Cardiology. Volume 28, April 2020, pp. 48-54, doi: 10.1016 / j.jvc.2020.03.002 , PMID 32339993 .

- ↑ DF Hogan: Feline Cardiogenic Arterial Thromboembolism: Prevention and Therapy. In: The Veterinary clinics of North America. Small animal practice. Volume 47, number 5, September 2017, pp. 1065-1082, doi: 10.1016 / j.cvsm.2017.05.001 , PMID 28662872 (review).

- ↑ JR Payne et al .: Risk factors associated with sudden death vs. congestive heart failure or arterial thromboembolism in cats with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. In: Journal of veterinary cardiology: the official journal of the European Society of Veterinary Cardiology. Volume 17 Suppl. 1, December 2015, pp. S318-S328, doi: 10.1016 / j.jvc.2015.09.008 , PMID 26776589 .

- ↑ CE Boudreau: An Update on Cerebrovascular Disease in Dogs and Cats. In: The Veterinary clinics of North America. Small animal practice. Volume 48, number 1, January 2018, pp. 45-62, doi : 10.1016 / j.cvsm.2017.08.009 , PMID 29056397 (review).

- ↑ Robert Goggs et al .: Pulmonary thromboembolism. In: Journal of veterinary emergency and critical care. Volume 19, Number 1, February 2009, pp. 30-52, doi : 10.1111 / j.1476-4431.2009.00388.x , PMID 19691584 (review).

- ↑ Karsten E. Schober and Imke Maerz: Assessment of left atrial appendage flow velocity and its relation to spontaneous echocardiographic contrast in 89 cats with myocardial disease. In: J Vet Intern Med , Volume 20, Number 1, 2006, pp. 120-130. doi : 10.1892 / 0891-6640 (2006) 20 [120: aolaaf] 2.0.co; 2 , PMID 16496931 .