John Douglas (architect)

John Douglas (born April 11, 1830 in Sandiway , Cheshire , England , † May 23, 1911 in Walmoor Hill , Dee Banks, Chester , England) was an English architect who designed around 500 structures in Cheshire, north Wales and the north-west England, including the country estate Eaton Hall . He learned his trade in Lancaster and worked in Chester. At first he worked alone, but from 1884 to two years before his death he was in a partnership with two of his previous assistants.

Douglas' work has included building new churches, refurbishing and renovating churches, church furnishings , new homes and remodeling existing homes, and a variety of other structures including shops, banks, offices, schools, monuments and public buildings. His architectural style was eclectic . Douglas worked in neo-Gothic architecture and many of his works incorporate elements of the Perpendicular Style . It was also influenced by architectural styles from mainland Europe and used features from French, German and Dutch architecture. Best known Douglas, however, was for its use of traditional elements in his building designs, especially of the framework , reflecting the popularity of the Tudorbethan belonging and-white Black revival is due in Chester. Other traditional elements he used in his work were the vertical wood paneling of the facade, stucco work and the use of decorative bricks to pattern surfaces and the construction of tall chimneys . The use of carpentry and very detailed wood carving are of special importance in Douglas' work .

During his career he has received assignments from wealthy landowners and industrialists, particularly the Grosvenor family at Eaton Hall. Most of his work still exists today, especially the churches he built. Many of his buildings are in Chester, with his half-timbered houses and the Eastgate Clock being the most visited. The greatest concentration of Douglas' structures is found in the Eaton Hall country estate and in the surrounding towns of Eccleston , Aldford and Pulford .

Life

Early life and education

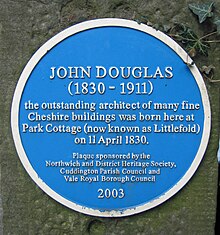

John Douglas was born in Park Cottage, Sandiway , Cheshire on April 11, 1830 and was baptized in St Mary's Church on May 16, 1830 . He was the second of a total of four children, but the only son of John Douglas and his wife Mary, née Swindley (1792–1863). John Douglas senior was born in Northampton about 1798-1800 and his mother was from Aldford , an Eaton Hall village in Cheshire; Douglas' maternal grandfather was the blacksmith of the Eccleston village, which was also part of Eaton. John Douglas was a bricklayer and carpenter who also measured buildings and traded in lumber. In 1835 he carried out the planning for a house in Hartford , a village between Sandiway and Northwich . At the time of the 1851 census it employed 48 workers. He owned land in Sandiway and a house with land in neighboring Cuddington.

Nothing is known about John Douglas junior's school days. He gained knowledge and experience in his father's business and in the workshop that was attached to the family home. In the mid or late 1840s he was a trainee lawyer at EG Paley of Sharpe and Paley in Lancaster , Lancashire . After the end of his legal traineeship, Douglas Paleys became chief assistant. Either in 1855 or 1860 he founded his own architectural office in No. 6 Abbey Square, Chester.

Family and personal life

Douglas had an older sister, Elizabeth, who was born in 1827, and two younger sisters named Mary Hannah and Emma, who were born in 1832 and 1834, respectively. Mary Hannah died five months before Emma was born and Emma died in 1848. Douglas married Elizabeth Edmunds, the daughter of a farmer from Bangor-is-y-Coed , Flintshire , on January 25, 1860 at St Dunawd's Church - in later years he would be her Renovate church. At first the couple lived in an apartment above the office in Abbey Square and a little later they moved to the neighboring house at number 4. During this time their five children were born, John Percy in 1861, Colin Edmunds in 1864, Mary Elizabeth in 1866, Sholto Theodore in the following year and finally Jerome in 1869. Only two of these children lived to see adulthood; Mary Elizabeth died of scarlet fever in 1868 , Jerome lived only a few days, and John Percy died in 1873 at the age of twelve.

In 1876 the family moved to 31 and 33 Dee Banks in Chester. The house was one of the partially connected houses above the River Dee that Douglas built. His wife died of laryngitis in 1878 after a year of illness, and Douglas never remarried. His son Colin learned the architectural profession and worked in his father's office, but died of tuberculosis in 1887 at the age of 23 . His other son Sholto is not known to have a profession, only that he was a heavy drinker. In the 1890s, Douglas built a house for himself, Walmoor Hill , which was also on the banks of the River Dee and overlooking the river. Douglas lived here until his death on May 23, 1911 at the age of 81. He was buried in the old Overleigh Cemetery in Chester. A memorial service was held the following Sunday at St John the Evangelist's Church, Sandiway. His legacy totaled just over £ 32,000 (around £ 3,270,000 in today's purchasing power). Apart from the structures that still exist, only two plaques remember John Douglas. One is in St Paul's Church , where Douglas went to church and which he also remodeled. The other is on one of the buildings he built on St Werburgh Street in Chester. It was installed by his students and assistants in 1923.

Practice and personality

Douglas practiced alone as an architect until his son Colin fell ill in 1884. He then partnered with Daniel Porter Fordham and the two worked under the name Douglas & Fordham. Fordham was born around 1846 and had been an assistant architect in the Douglas law firm since at least 1872. In 1898 Fordham withdrew from the partnership because of a tuberculosis disease and a year later he died in Bournemouth , where he had previously moved. His successor in Douglas' architecture office was Charles Howard Minshull, born in Chester in 1858, who had become a trainee lawyer in the architecture office in 1874, and from then on the two worked as Douglas & Minshull. From 1900 Douglas was less active, and for reasons unknown today, the partnership was broken in 1909. Minshull partnered with architect E. J. Muspratt, whose office was on Foregate Street, Chester. When Douglas died in 1911, however, the architecture firm Douglas, Minshull & Muspratt existed in Abbey Square.

Little is known about Douglas' personal life and personality; only two photographs of him have survived. One photograph shows him in his middle age, the other shows a caricature drawing that an assistant made of him in his office. He is shown in old age, bent and stooped, with an ear trumpet, glasses and briefcase.

Architectural historian Edward Hubbard called his life "apparently [...] one of the full dedication of architecture ... which may have been compounded by the death of his wife and other private worries". The Obituary for Douglas in the Chester Chronicle stated that he "lived with heart and soul in his profession."

Douglas was a professed Christian who regularly attended his local church, St Paul's. There was an oratorio at his Walmoor Hill home . He also had a strong sense of national loyalty, with statues of Queen Victoria set up in niches in Walmoor Hill and his homes on St Werburgh Street, Chester. Douglas struggled to handle the financial aspects of his profession. The secretary of the 1st Duke of Westminster wrote about him in 1884 that he was “a good architect, but sloppy with accounts!” Delays in submitting the accounts often led to difficulties and confusion, in some cases he did not put up until ten Years ago his reckoning. Little is known about the other circumstances of his private life, no papers from the family estate have been preserved, and none of the documents from his architectural office in Abbey Square.

Create

Works and customers

Douglas has designed over 500 buildings. He built at least 40 new churches or chapels and renovated, expanded or rebuilt numerous others; He also designed fittings and furniture for churches. He designed new houses and carried out extensions, as well as planning outbuildings for these houses. Douglas works also include farms, shops, hotels, a hospital, clock towers, schools, bathhouses, a library, a bridge, an obelisk , cheese factories, and public toilets. His architectural practice was in Chester and so most of his work was carried out in Cheshire and north Wales, although he had projects further afield, such as Lancashire , Staffordshire , Warwickshire and Scotland.

During his career, Douglas has received assignments from wealthy and influential clients. The first known independent work was a now-defunct ornament for the garden of the sister-in-law of Hugh Cholmondeley, 2nd Baron Delamere and it was the Baron who commissioned Douglas in 1860 with the first major order, a considerable new construction of the south wing of his seat of the Vale Royal Abbey . Around the same time, Lord Delamere hired him to build St John the Evangelist's Church in Over , Winsford , in memory of his first wife. Douglas' main customers were the Grosvenor family from Eaton Hall. In 1865 he was commissioned by Richard Grosvenor to build the gatehouse and other structures for Grosvenor Park in Chester and St John's Church in the village of Aldford. When he died in 1869, his son Hugh Grosvenor followed him . Douglas received a number of other commissions from him and his son in the course of his career. It is believed that for the 1st Duke in the area belonging to Eaton Hall he would have four churches and chapels, rectories and large houses, about 15 schools, about 50 farmhouses, about 300 cottages , huts, blacksmiths , two factories, two guest houses and planned about a dozen commercial buildings. He also designed buildings on the Halkyn manor owned by the Duke in Flintshire , including another church.

Among the other wealthy landlords who hired Douglas to work were William Molyneux, 4th Earl of Sefton , Francis Egerton, 3rd Earl of Ellesmere , George Cholmondeley, 5th Marquess of Cholmondeley , Rowland Egerton-Warburton of Arley Hall and in Wales the families of Lord Kenyon and the Gladstone family, including William Ewart Gladstone . He has also received industry contracts, including from John & Thomas Johnson , a soap and alkaline maker from Runcorn , Richard Muspratt , a chemical company from Flint , Flintshire, and W. H. Lever , a soap maker who also built the Port Sunlight workers' estate .

style

Although the architecture firm Douglas trained in was in a provincial town in the north of England, it was one of the pioneers of neo-Gothic architecture in the country. Neo-Gothic architecture was a reaction to Classicism , popular in the 18th and early 19th centuries, and used features of the Gothic architectural style of the Middle Ages . Both Edmund Sharpe and EG Paley were influenced by the Cambridge Camden Society and in particular by Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin , who believed that "Gothic was the only correct and Christian way of building". Sharpe was also influenced by Thomas Rickman and had written about medieval scholarship himself. Paley, in turn, was influenced by his brother Frederick Apthorp Paley , who was a fan of Gothic architecture and was himself inspired by Rickman. During Douglas's time in Lancaster, Sharpes and Payles architects were responsible for the construction and renovation of neo-Gothic buildings such as St Wilfrid's Church in the village of Davenham , Cheshire, just three miles from Sandiway, the birthplace by Douglas. Douglas' first own church building was St John the Evangelist in Over , Winsford . He was completely guided by the decorated style .

The influences on Douglas' work were not limited to England. Although he never traveled abroad, he picked up Gothic style elements from the continent, particularly from Germany and France. This combination of various Gothic and Neo-Gothic styles contributed to what eventually became known as the High Victorian . The characteristics include a sense of bulkiness, steep roofs, which are often designed as a gable roof . round tourelles with conical roofs, pinnacles , heavy cornices supported on consoles and the use of polychromy . Much of Douglas' works, especially his earlier work, are done in this style, or at least use architectural features of the style. A characteristic feature of Douglas' work is the use of dormer windows , which rise up from the eaves and are covered by gable roofs.

Another major influence on his work was the increased interest in traditional architecture. There was a black-and-white revival by the time Douglas moved to Chester , and Douglas incorporated this style into the buildings he carried out in Chester and elsewhere. This revival of half-timbered architecture did not start in Chester, but has become a typical Chester construction. The first Chester architect to adopt this style was Thomas Mainwaring Penson , whose first work in the field was the renovation of a store on Eastgate Street in the early 1850s. Other architects in the city who quickly adopted the style were T. A. Richardson and James Harrison ; However, it was essentially enforced and developed by Thomas Lockwood and Douglas. The first structure known to use this black-and-white style was an early work for the Grosvenors, the porter's lodge at Grosvenor Park, which used timber-framed upstairs. Other traditional motifs of English architecture that Douglas used came from the Tudor style . This included the hanging wooden paneling, stucco facades and massive brick chimneys. Here Douglas was influenced by the architects William Eden Nesfield and Richard Norman Shaw . Douglas also used traditional elements from the continent, especially brickwork from Germany and the Netherlands.

Typical of Douglas' creative style is the attention he paid to details of the exterior and interior alike. These detailed work were not taken from a specific style, but he chose architectural elements of any style that was particularly appropriate to the purpose of the respective project. This is particularly true of the carpentry work, perhaps inspired by the experiences he gathered in his father's workshop in his youth and was applied to both wooden components and the furniture he designed. Another continental influence that Douglas took was the Dutch style volute gables . But the most important and continuously used element in Douglas' designs was the use of the framework in parts of the building. When building the Rowden Abbey and the St Michael and All Angels Church by Altcar, he relied exclusively on the half-timbered construction.

Significant structures

Early work (1860–1870)

Douglas' earliest significant assignments were for the 2nd Baron Delamere and were different from one another. The construction of a new wing of the Vale Royal Abbey (1860) was carried out in the Elizabethan style, while the St John's Church at Over (1860-63) was based on the Early Decorated Style as a Gothic Revival . The Congregational Chapel (1865), also in Over, was again a different style and was designed in a polychrome brick arrangement in Victorian Gothic . Meanwhile, Douglas also designed a store at 19-21 Sankey Street in Warrington (1864), which had Gothic arcades and detailed stone carvings . Hubbard described this building as his "first structure of real and outstanding quality ... in its own way one of the best things he has ever done." A short time later he received his first orders for the Grosvenor family, a porter's house and other buildings in Grosvenor Park (1865–1867), and St John the Baptist's Church in Alford (1865–1866).

The first house he planned was Oakmere Hall (1867), which the owners of John & Thomas Johnson from Runcorn entrusted him with planning . It is built in the Victorian High Gothic style and consists of a main wing and a side wing as well as a small tower with tourelles, a large tower on the south facade and a driveway for carriages. The roof has steep surfaces and dormers. Another early church building in the work of the architect was St Ann's Church in Warrington (1868-69), again built in the Victorian High Gothic. Around 1869-1870, Douglas began designing buildings for the Eaton Hall manor.

Early mature buildings (1870–1884)

Secular buildings

Many of the secular buildings Douglas constructed during this period were more of a smaller structure. These included cottages in Great Budworth and cottages, houses, schools and farms in Eaton Hall and its villages. In 1872 he designed Shotwick Park , a large, timber-framed brick house in Great Saughall ; the house has steep roofs, high chimneys and several tourelles. Around the same time, Douglas was redesigning Broxton Higher Hall . Douglas received orders for larger houses in the late 1870s and 1880s. The Gelli (1877) is a three wing house that he built for the Kenyon siblings in Tallarn Green, Flintshire . Douglas Llannerch also designed Panna in Penley , Flintshire (1878–79) for this family, which is noticeable for its carpentry work. Rowden Abbey (1881) in Hertfordshire is a complete framed black-and-white house . North Wales Plas Mynach (1883) in Barmouth has extensive detailed woodwork on the interior.

About 1879-1881 Douglas built a row of houses on his own property in Chester, 6-11 Grosvenor Park Road , on the road leading to the main gate of Grosvenor Park. This row of houses was built in the Victorian High Gothic style. Around 1883 he designed Barrowmore Hall (also known as Barrow Court) in Great Barrow (has since been demolished), one of the largest houses built by Douglas. Around the time, Eaton Hall Eccleston Hill (1881–82), a large house for the Duke's secretary, Stud Lodge , Eccleston Hill Lodge (1881), a three-story gatehouse at the main entrance to the park and The Paddocks (1882–83 ), another large house, this one for the Duke's land manager. In the center of Chester he created Grosvenor Club and North and South Wales Bank (1881–83) on Eastgate Street, built of stone and brick with turrets and stepped gables and 142 Foregate Street for Cheshire County Constabulary (1884) with a Flemish-style gable .

Churches

1874-1875 renewed Douglas for the 2nd Baron Delamere St Mary's Church in Whitegate, whereby a large part of the medieval interior was preserved and especially the outside of the building was rebuilt, mainly by adding a short choir and the framework. St Paul's Church in Boughton was the parish church that Douglas himself visited and which he rebuilt in 1876, incorporating parts of the existing structure. Douglas' only timber-framed church is the small church of St Michael and All Angels in Great Altcar , Lancashire . St Chad’s (1881) in Hopwas in Staffordshire was built partly from bricks and partly as a half-timbered building . During this period, Douglas also built and renovated a number of churches made entirely of stone, mainly combining Gothic style features with traditional elements. These buildings also include St John the Baptist's Church in Hartford (1873–75), St Paul's in Marston (1874, demolished), the Presbyterian Chapel (1875) in Rossett , Denbighshire , St Stephen’s in Moulton (1876), the renovation the Christ Church in Chester (also 1876), the Church of St Mary the Virgin (1877-78) of Halkyn in Flintshire and the Walliser Church of St John the Evangelist (1878) in Mold in the same county. Later in this creative period the built St Mary's Church in Pulford (1881–1884) was commissioned by the Duke of Westminster and St Werburgh's New Church in Warburton for Rowland Egerton-Warburton from 1882–1885 .

Partnerships

Douglas & Fordham (1884–1898)

Douglas & Fordham drew from 1885-1887 for William Molyneux, 4th Earl of Sefton Abbeystead House in North Lancashire. Hubbard describes this building as "the finest of Douglas' Elizabethan houses and one of the largest he has ever designed". During this time, Jodrell Hall in Cheshire and Halkyn Castle in Flintshire were also expanded. In 1885 the Castle Hotel in Conwy , Caernarfonshire was rebuilt and built in 1887–1888 at Hawarden Castle a vault ; it was followed by a veranda in 1890. During this time, the Eaton Hall manor was also built, including houses and cottages such as Eccleston Hill and the Eccleston Ferry House, and farms such as Saighton Lane Farm . In 1890–91 an obelisk was erected at the entrance to Eaton Hall from Belgrave Avenue.

The last major house Douglas designed was Brocksford Hall (1893) in Derbyshire. It was a country house in the Elizabethan style with a clock tower, whereby stucco work was combined with bricks and stones. In the center of Chester a timber frame house was built at 38 Bridge Street in 1897, which included a section of the Chester Rows and has many decorative wood carvings. From 1892 on, the architecture firm built houses and cottages in Port Sunlight for the Lever brothers. In addition, Douglas and Fordham constructed the Dell Bridge (1894) and from 1894 to 1896 what is now called the Lyceum school.

In 1896, Douglas also built a house for himself: Walmoor Hill was built on the Dee Banks in Chester in the Elizabethan style. Between 1895 and 1897 he also designed a row of houses on the east side of St Werburgh Street in central Chester. At the south end, on the corner of Eastgate Street, is a bank, the ground floor of which is brick. Behind it, the ground floors along the street consist of shop fronts. Above it sit two floors with an attic , which are constructed with heavily decorated half-timbered beams. On the first floor there are a number of bay windows , the second floor is built in frame construction and the top floor spans eleven gables . Nikolaus Pevsner rated this row of buildings as "Douglas in top form (although also as extremely boastful)".

During the existence of the partnership, Douglas continued work on building new churches and renovating old church buildings. 1884-1885 he built a chapel in Carlett Park of Eastham on the Wirral Peninsula and 1884-87 St Deiniol's Church in Criccieth , Caernarfonshire . Christ Church (1886–92), St Paul's Church , Colwyn Bay (1887–1888 with later extensions) and St Andrew's Church , West Kirby (1889–91) followed. St John's Church in Barmouth , Merionethshire was built between 1889 and 1895 and is one of the largest churches that Douglas built; however, the church tower collapsed during construction in 1891 and had to be rebuilt. Other churches that Douglas built in north Wales were Christ Church in Bryn-y-Maen, Colwyn Bay, and All Saints Church in Deganwy (both 1897-1899).

Around 1891/1892 Douglas built the Church of St James the Great in Haydock . This was partly built as a half-timbered structure in order to better arm the structure against possible mountain damage . Other new churches built during the partnership with Fordham were St Wenefrede's Church (1892) in Bickley, St David's Welsh Church in Rhosllannerchrugog in Denbighshire , All Saints Church in Higher Kinnerton (1893), the Congregational Church in Great Crosby ( 1897–1898), and St John the Evangelist's Church (Weston) in Weston, Runcorn (1897–1900). He built a spire in 1886–1887 for St Peter's Church in Chester and a tower was added to Holy Trinity Church in Capenhurst around 1889–1890 under his supervision . As early as 1886–1887, Douglas had built a bell tower for St John the Baptist's Church in Chester. This construction measure was followed by a new building of the north aisle. In addition, church renovations and embellishments were carried out during this period, monuments were added and Douglas also furnished churches.

Douglas & Minshull (1898–1909) and Douglas alone (1909–1911)

In 1898 Douglas and Minshull designed St Oswald's Chambers on St Werburgh Street in Chester. As a result, other buildings were built in the city. 1902-1903 built Douglas the St John the Evangelist's Church in his birthplace Sandiway. It was built on a piece of land that belonged to him and he financed the construction of the choir and the roofed churchyard gate. In 1899, in honor of Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee in 1897, the Diamond Jubilee Memorial Clock was built in an open wrought-iron structure on Eastgate in Chester . 1898-1901, the architectural firm carried out the construction of Chester's public bath house ; This was an unusual job for Douglas, as it required special engineering work. During this period one of Douglas' most important non-ecclesiastical buildings, St Deiniol's Library in Hawarden , Flintshire, was built for W. E. Gladstone and his family. The first phase of construction took place between 1899 and 1902, and the library was completed in 1904–1906. Around this time, the architecture firm was also commissioned to build two new churches, which Gladstone was involved in building; St Ethelwold's (built 1898-1902) was a new church in Shotton in Flintshire and St Matthew's in Buckley in the same county was expanded between 1897 and 1905. The other new churches built during this period were the only church Douglas built in Scotland - Episcopal Church (1903) in Lockerbie , Dumfriesshire - and St Matthew's Church (1910-11) in Saltney , also in Flintshire. Changes to other churches and church facilities were also designed. Douglas' last major project was to add a church tower to the St Paul's in Colwyn Bay he had built, but he died before completion.

Publications

Douglas did not publish his own texts and did not leave a record of his ideas and thoughts. The only publication he was involved in was the Abbey Square Sketch Book , which he edited. The book was published in three volumes, the first being dated 1872, the others being undated; the work consists of sketches and plans, including some photographs in the third volume, by many different authors. The images show buildings and furniture, mostly from the late Middle Ages and the 16th to 17th centuries, mostly from Cheshire and north-west England. Douglas' only contribution was a jointly ascribed panel in the third volume. It is likely that he designed the front pages, or at least the drawings of the Abbey Gateway in Chester on them.

Recognition, Influence, and Legacy

Douglas worked in a provincial county town throughout his career, and his work is concentrated in Cheshire and north Wales, yet "he practiced a practice that became nationally renowned". He was never a member of the Royal Institute of British Architects , but his work has been featured in national publications including Building News , The Builder , The Architect and The British Architect ; especially the last of this series has praised much of his work. A number of his designs have been exhibited by the Royal Academy and printed in Academy Architecture . The obituary for him in The British Architect described him as an architect who "has achieved a reputation that has long placed him at the forefront of living architects". In his series The Buildings of England , Nikolaus Pevsner described him without reservation as “the best architect in Cheshire”. In The Buildings of Wales: Clwyd , Edward Hubbard expressed the opinion that he was "the most important and active local architect of his time". The positive criticism was not limited to the British area, Douglas' work was also praised by the French architect Paul Sédille and the German architect and author Hermann Muthesius . However, a medal for his Abbeystead House design , which was shown at an exhibition in Paris, was the only official recognition of his work during his lifetime.

Many of the architects who were trained and worked in Douglas' architectural practice were influenced by his style. Perhaps the most famous among them were Edmund Kirby and Edward Ould . Kirby is well known for its Roman Catholic churches, and Ould designed a number of Douglas-style structures in and around Chester, including Wightwick Manor and various buildings at Port Sunlight . Other architects who did not work with him in an architectural office were also influenced by him; among them are Thomas Lockwood , Richard Thomas Beckett, Howard Hignett, AE Powers, James Strong and the Cheshire County Architect Henry Beswick.

A large number of John Douglas' buildings still exist, many of which are listed buildings . Douglas' work is not focused on one type of building; its churches and houses are of equal importance. Douglas was not a pioneer of any particular new development, but followed national trends in architecture while maintaining his individual style. His works are “anything but plagiarism” and they “have a highly individual and almost always recognizable note”. The main characteristics of his structures are "safe proportions, imaginative structures and groupings ... flawless detailing and a great understanding of craftsmanship and a feel for materials". His works are “architecture that can be enjoyed as well as admired”.

bibliography

- Edward Hubbard: The Buildings of Wales: Clwyd ( English ). Penguin, London 1986, ISBN 0-14-071052-3 .

- Edward Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas ( English ). The Victorian Society, London 1991, ISBN 0-901657-16-6 .

- Nikolaus Pevsner : The Buildings of England: North Lancashire ( English ). Yale University Press, New Haven / London 2002, ISBN 0-300-09617-8 .

- Nikolaus Pevsner, Edward Hubbard: The Buildings of England: Cheshire ( English ). Yale University Press, New Haven / London 2003, ISBN 0-300-09588-0 .

- Richard Pollard, Nikolaus Pevsner: The Buildings of England: Lancashire: Liverpool and the South-West ( English ). Yale University Press, New Haven / London 2006, ISBN 0-300-10910-5 .

Web links

supporting documents

- ↑ Peter Howell: Douglas, John (1830-1911). In: Henry Colin Gray Matthew, Brian Harrison (Eds.): Oxford Dictionary of National Biography , from the earliest times to the year 2000 (ODNB). Oxford University Press, Oxford 2004, ISBN 0-19-861411-X , ( oxforddnb.com license required ), Last updated: 2004, accessed January 22, 2008.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 1f.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 3-4.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. p. 1.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 4-5.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 5-9.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. p. 13.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. p. 17.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 6-7.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 10-11.

- ^ A b Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. p. 11.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. p. 15.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 15-16.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. p. 29.

- ^ A b c Hubbard: The Buildings of Wales. 1986, p. 74.

- ^ A b Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 238-279.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. p. 27.

- ^ A b Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. p. 28.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991, p. 60.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 63-64.

- ^ A b Roger King: John Douglas 1830-1911 ( English ). Northwich and District Heritage Society, Northwich, p. 6.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. p. 254.

- ^ Edwin Smith, Hutton, Graham and Cook, Olive: English Parish Churches ( English ). Thames & Hudson , London 1979, ISBN 978-0-500-20139-8 , pp. 211-214.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. p. 19.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 19-21.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. p. 22.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. p. 41.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 38-58.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. p. 47.

- ↑ Topography 900–1914: Victorian and Edwardian, 1840–1914 . In: Christopher P. Lewis, Alan Thacker (ed.): A history of the county of Chester (= Victoria history of the counties of England ). Nand 5: The city of Chester , Part 1: General History and Topography . Victoria County History, London 2004, OCLC 71122398 , p. 229–238 (English, British-history ( memento of October 28, 2011 in the Internet Archive )).

- ^ Pevsner, Hubbard: The Buildings of England: Cheshire. 2003, p. 38.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 25-26.

- ^ Pevsner, Hubbard: The Buildings of England: Cheshire. 2003, p. 39.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 47-48.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 77-80.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 82-88.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991, p. 93.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. p. 95.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 109, 126-127.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 40-42.

- ^ Pevsner, Hubbard: The Buildings of England: Cheshire. 2003, p. 368.

- ^ A b Pevsner, Hubbard: The Buildings of England: Cheshire. 2003, p. 389.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 43-44.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 44-46.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 46-48.

- ^ Pevsner, Hubbard: The Buildings of England: Cheshire. 2003, p. 160.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. p. 48.

- ^ Pevsner, Hubbard: The Buildings of England: Cheshire. 2003. pp. 57-58.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 50-53.

- ^ A b Pevsner, Hubbard: The Buildings of England: Cheshire. 2003, p. 333.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 55-56.

- ^ Pollard, Pevsner: The Buildings of England: Lancashire: Liverpool and the South-West. 2006, p. 621.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991, p. 62.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 79-101.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 114-115, 243.

- ^ Pevsner, Hubbard: The Buildings of England: Cheshire. 2003, p. 229.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 105, 107.

- ^ Pevsner, Hubbard: The Buildings of England: Cheshire. 2003, p. 117.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 104-105.

- ^ Hubbard: The Buildings of Wales. 1986. p. 445.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 107-109.

- ^ Hubbard: The Buildings of Wales. 1986. p. 416.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991, p. 109.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 109-111.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 112-114.

- ^ Pevsner, Hubbard: The Buildings of England: Cheshire. 2003, p. 164.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 116-118.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 118-120.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 120-123.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 124-125.

- ^ Pevsner, Hubbard: The Buildings of England: Cheshire. 2003. pp. 381-382.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 125-126.

- ^ Pevsner, Hubbard: The Buildings of England: Cheshire. 2003. pp. 172-173.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 126-127.

- ^ Pollard, Pevsner: The Buildings of England: Lancashire: Liverpool and the South-West. 2006, pp. 179-180.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. p. 127.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 130-137.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 137-139.

- ^ Pevsner, Hubbard: The Buildings of England: Cheshire. 2003, p. 317.

- ^ Pevsner, Hubbard: The Buildings of England: Cheshire. 2003, p. 376.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991, p. 149.

- ↑ Pevsner, 2002. Page 186.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991, p. 151.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991, p. 155.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991, p. 157.

- ^ Hubbard: The Buildings of Wales. 1986. pp. 362-364.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 158-166.

- ^ A b Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991, p. 166.

- ^ Pevsner, Hubbard: The Buildings of England: Cheshire. 2003, p. 212.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 155-156.

- ^ Pevsner, Hubbard: The Buildings of England: Cheshire. 2003, p. 167.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 168-171.

- ^ Pevsner, Hubbard: The Buildings of England: Cheshire. 2003. pp. 307, 312-313.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991, p. 188.

- ^ Pevsner, Hubbard: The Buildings of England: Cheshire. 2003. pp. 173-174.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 189-190.

- ↑ Images of England: 2-18 St Werburgh St, Chester ( English ) English Heritage . Archived from the original on October 24, 2012. Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Retrieved March 25, 2010.

- ^ Pevsner, Hubbard: The Buildings of England: Cheshire. 2003, p. 162.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991, p. 173.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 173-177.

- ^ Pevsner, Hubbard: The Buildings of England: Cheshire. 2003, p. 379.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 177-178.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 179-181.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 181-182.

- ^ Pollard, Pevsner: The Buildings of England: Lancashire: Liverpool and the South-West. 2006, pp. 195-196.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991, p. 182.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. p. 262.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. p. 263.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 184, 268.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 183-184.

- ^ Pevsner, Hubbard: The Buildings of England: Cheshire. 2003. pp. 380-381.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991, p. 184.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 184-185.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 185-186.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. p. 192.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 192-196.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 194-195.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991, p. 196.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 196-197.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 198-200.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 200-202.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. p. 274.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 202, 276.

- ^ Hubbard: The Buildings of Wales. 1986. p. 443.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 202-204.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. p. 204.

- ^ Hubbard: The Buildings of Wales. 1986. p. 135.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 11-13.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. p. 23.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 32-34.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. p. 34.

- ^ Pevsner, Hubbard: The Buildings of England: Cheshire. 2003, p. 35.

- ^ Hubbard: The Buildings of Wales. 1986. p. 73.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 34, 36.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 205-207.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991. pp. 209-210.

- ^ Hubbard: The Work of John Douglas. 1991, p. 210.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Douglas, John |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | English architect |

| DATE OF BIRTH | April 11, 1830 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Sandiway , Cheshire , England |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 23, 1911 |

| Place of death | Walmoor Hill , Dee Banks, Chester , England |