Kingdom of Navarre

|

Kingdom of Navarre Nafarroako Erresuma / Reino de Navarra |

|

Coat of arms (1234–1580) of the Kingdom of Navarre |

|

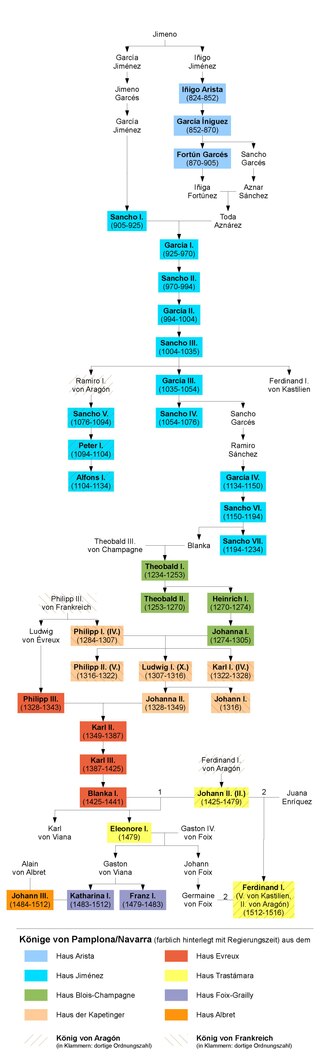

| Monarchs | List of the kings of Navarre |

| religion |

Roman Catholic Calvinist (1560–1593) |

| founding | at 824 |

| resolution | 1620: Basse-Navarre 1841: Alta Navarra |

The Kingdom of Navarre ( Spanish Reino de Navarra , French Royaume de Navarre ) was founded around 824 in the western Pyrenees region . In 1512 it was divided into a part oriented towards Spain and a part oriented towards France (Upper Navarre, Spanish Alta Navarra or Lower Navarre, French Basse-Navarre ). Lower Navarra was united with the Kingdom of France in 1620, while Upper Navarra was dissolved in 1841 and became a province in the Spanish central state.

After the name of their royal seat, the first kings of Navarre initially bore the title "King of Pamplona"; not until Sancho VI. called himself "King of Navarre" (1162).

Origin and the House of Arista (824–905)

After the Arab invasion of the Iberian Peninsula in 711, the area of the later Kingdom of Navarre also came under Moorish rule. At the beginning of the 9th century, the Franks founded a number of counties ( Spanish marks ) as an advanced line of defense against the Moors in the south of the Pyrenees . The area around the city of Pamplona came under Franconian influence. Around 816, the native Christian aristocratic family Arista succeeded in driving out the Frankish governor with the support of the originally Christian, but at that time already converted to Islam, noble family of the Banu Qasi . When a Moorish army was defeated in 824, the Pamplona Kingdom was born, and Iñigo Arista is considered its first king. Over the next two centuries, the small kingdom had to fight off attacks from the Moors more frequently, but was able to defend its autonomy.

Under the Jiménez House (905–1234)

After the death of the last ruler of the House of Arista, Fortún Garcés († 905), Sancho I, the husband of Fortún's granddaughter, seized power and established the House of Jiménez as a new dynasty. His successor García I acquired the county of Aragón by marriage in 925 . In 934 an army of the Caliph Abd ar-Rahman III attacked and devastated . Parts of Navarre, but already 70 years later the kingdom under Sancho III. (1004–1035) the climax of the development of power; around 1020 he conquered the east bordering Pyrenees counties Sobrarbe and Ribagorza and in 1029 also became Count of Castile. He rose to become the most powerful Christian ruler of the Iberian Peninsula.

But he divided the territory in his will among his sons: García III. became king of Pamplona and Ramiro I first king of Aragón, while Gonzalo received the counties of Sobrarbe and Ribagorza and Ferdinand the county of Castile. A little later, Ferdinand was able to gain control of the Kingdom of León and thus became the first king of the united Castile-León.

The kingdom of Pamplona did not last long after that: Sancho IV of Navarre , son of Garcías III, was murdered in 1076. His cousins Sancho von Aragón and Alfons VI took advantage of the confused situation . from Castile and Leon to divide Pamplona among themselves. The Aragonese received the eastern part and became King of Pamplona as Sancho V.

This part of Pamplona, which fell to Aragón in 1076, became independent again as the Kingdom of Navarre in 1134 after Alfonso I of Aragon died childless. While his brother Ramiro succeeded him on the throne in Aragón, García IV , a great-grandson of García III, was proclaimed king in Navarra . However, the territory of Navarre had a strategic disadvantage that hindered its further development: except in the north, it was enclosed by Castile-León and Aragón, so that, unlike the other Christian states of the Iberian Peninsula, it was not at the expense of the Moors during the Reconquista could expand and enlarge southwards.

Under French influence (1234–1425)

In 1234 King Sancho VII died without a legitimate descendant. He was succeeded by his nephew Theobald I , who was a son of his sister Blanka and her husband Theobald von Champagne . For the first time a ruler from the French house of Blois-Champagne came to the throne of Navarre, after it had previously sought a stronger bond with France in order to free itself from the encirclement of Castile and Aragon.

King Henry I (1270–1274) was inherited by his only two-year-old daughter Johanna I , who was married in 1284 to a son of the French king, who ascended the French throne as Philip IV in 1286 and as Philip in the history of Navarre I. received. Until 1328 all French monarchs from the house of the Capetians were also kings of Navarre.

After the Capetians died out - Charles IV of France (in Navarre: Charles I) died childless in 1328 - Navarre was able to break away from France: The Salic law applicable to France excluded female succession to the throne. This did not apply to Navarre, however, so that Charles's niece Johanna II and her husband Philip III. from the house of Évreux came to the throne, while in France Philip VI. became king of Valois . Although Navarre was surrounded by powerful neighbors (Castile-León, Aragón, France and England, which occupied Aquitaine during the Hundred Years War ), the small kingdom was able to maintain its independence - albeit with difficulty.

Inner turmoil and decline (1425-1516)

With the death of Charles III. (1387–1425) a long time of inner turmoil began, in which the aristocratic parties of the Agramonteses and the Beaumonteses faced each other:

Karl's daughter Blanka had married Johann , a brother of the Aragonese king, in 1419 . When Charles III. died, both ascended the throne of Navarre. Blanka I. died in 1441 and left her widower and a son, Karl von Viana , along with two daughters . There was a conflict between Johann, the father, supported by the Agramonteses, and Karl, the son, supported by the Beaumonteses, when Johann remarried in 1444. In 1458, following the death of his brother, John also became King of Aragón. Charles von Viana died in Barcelona in 1461, and it was rumored that his father had a hand in it.

When Johann died in 1479, Eleanor , a daughter from his marriage to Blanka, inherited the crown of Navarre. Eleanor herself died a few weeks later. She was succeeded on the throne by her twelve-year-old grandson Franz I , who in turn was only supported by one of the aristocratic parties and died four years later childless. His thirteen-year-old sister, Katharina , became queen, and her claim to the throne remained just as controversial as that of her predecessors.

Division between Spain and France

The dispute between Agramonteses and Beaumonteses resulted in a civil war in 1512 , in which Fadrique Álvarez de Toledo conquered the part of Navarre south of the Pyrenees ridge for Ferdinand II of Aragon . In the name of his second wife Germaine de Foix , who was a cousin of Queen Katharina, Ferdinand claimed the throne of Navarre and, after conquering the southern part of this kingdom, assumed the title of "King of Navarre", which has since been awarded to all the kings of Aragon (and Spain) led.

After Aragon had conquered most of Navarre, including the capital Pamplona , Catherine and her husband Johann von Albret were able to retain control of the smaller part of the kingdom north of the Pyrenees ridge. This area was called " Lower Navarre " (French: Basse Navarre ). Larger towns were Luxe-Sumberraute , Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port and Saint-Palais . The Albret did not give up their claim to the entire empire. Henry II received military support from Francis I of France , who in 1521 appointed the general André de Foix to head an army with the task of retaking the lost territories of Navarre. The campaign failed after initial successes with complete defeat and the capture of the military leader.

In fact, the campaign of 1521 marked the last attempt for the House of Albret to recapture the southern part of Navarre. And although the claims of Albret passed to the House of Bourbon in 1572 , which also acquired the French royal throne in 1589, no serious efforts were made to gain possession of the territories.

In the Union edict of 1620 , the status of Basse-Navarres as an independent kingdom was abolished by Louis II (XIII) , i.e. Lower Navarre was administratively and institutionally united with the neighboring Béarn and thus became part of one of the provinces of the French crown lands. However, both areas had already been administered together before the edict, as both the Béarn and Lower Navarra had belonged to the Albret: Henry II of Navarre (1503–1555) had already raised the Barnesian capital Pau to his residence.

After the French Revolution , the area of Lower Navarre was integrated into the newly created department of Basses-Pyrénées (today: Pyrénées-Atlantiques ) and there in turn divided into the cantons of La Bastide-Clairence , Hasparren , Iholdy , Saint-Étienne-de-Baïgorry , Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port and Saint-Palais .

In their titles, the French kings carried the Navarre royal title until 1791 and again during the Restoration from 1814 to 1830 on an equal footing with the name of France ("roi de France et de Navarre").

The "Upper Navarra" (Spanish: Alta Navarra ), ruled by the Catholic Monarchs since 1512 , initially remained as an independent kingdom, ruled by the rulers of Castile and Aragon in personal union. These were represented here by a viceroy . Even after the War of Spanish Succession (1701-1714) Navarre could assert its rights, as it on the part of the victorious Bourbon Philip V had stood. During the French occupation from 1810 to 1814, the Kingdom of Navarre was abolished and converted into a prefecture, but it regained its autonomy after the restoration of Bourbon rule. This was lost again shortly afterwards in the Spanish Revolution ( Trienio Liberal , 1820–1823); In 1822 the province of Navarre was created, but it was abolished in 1823 after the French invaded again (under the Duc d'Angoulême ). During the first Carlist War (1833-1840), the Navarre estates supported the Carlist pretender against Isabella II of Spain . When this won, their government decided on August 16, 1841 the final abolition of the Navarres Cortes and Fuero and made the country a province of the Spanish central state. Nevertheless, the title of King of Navarre is preserved in the Spanish royal statute to this day.

Only with the adoption of the Statute of Autonomy on August 10, 1982, Navarra received the status of an autonomous regional authority again as a so-called "Foral Community" (Spanish: Comunidad Foral de Navarra ) within the borders of Alta-Navarra and with Pamplona as the capital.

The Basque national movement regards all of Navarre north and south of the Pyrenees as one of the historical territories of the Basque Country , even if the Basque language is only spoken in the northern part of the Spanish region and in parts of the French Lower Navarre.

See also

literature

- J. Azurmendi: The importance of language in the Renaissance and Reformation and the emergence of Basque literature in the religious and political conflict area between Spain and France. In: Wolfgang W. Moelleken, Peter J. Weber (Hrsg.): New research on contact linguistics . Dümmler, Bonn 1997. ISBN 978-3-537-86419-2

- Spanish mark. In: Meyers Konversations-Lexikon. 4th edition. Volume 15, Verlag des Bibliographisches Institut, Leipzig / Vienna 1885–1892, p. 98.

- P. Schmidt (Hrsg.): Small history of Spain. Reclam, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-15-017039-7 .

- C. Collado Seidel: Short history of Catalonia. CH Beck, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-406-54787-4 , p. 18 ff. (Limited preview in the Google book search).

- DW Lomax: The Reconquista. The reconquest of Spain by Christianity. Heyne, Munich 1980, ISBN 3-453-48067-8 .

- AR Lewis: The Development of Southern French and Catalan Society 718-1050. Ed .: The Library of Iberian Resources online. The University of Texas Press, 1965, p. 322.

- Detlev Schwennicke : European family tables. Volume II (1984).

- M.-A. Caballero Kroschel: Reconquista and Imperial Idea. The Iberian Peninsula and Europe from the conquest of Toledo (1085) to the death of Alfonso X (1284). Krämer, Hamburg 2008, ISBN 978-3-89622-090-5 .

- K. Herbers: History of Spain in the Middle Ages. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-17-018871-2 .

- MH d'Arbois de Jubainville: Histoire des Duc et des Comtes de Champagne I-IV, Paris 1859–1865, V-VI: Catalog des Actes des Comtes de Champagne, Paris 1863 and 1866.

- E. Garnier: Tableaux généalogiques des souverains de France et des ses grands feudataires, Paris 1863.

- L. Dussieux: Généalogie de la Maison de Bourbon, 2nd edition, Paris 1872.

- Wilhelm Prinz von Isenburg: Family Tables on the History of the European States, 2 volumes, Marburg 1953.

- F. de Béthencourt: Historia genealogica y heraldica de la monarquia espagnola, 9 volumes, Madrid 1879ff.

- H. Virgnault: Généalogie de la maison de Bourbon, 1949.

- G. Sirjean: Encyclopédie généalogique des Maisons Souveraines du Monde, 13 volumes, Paris 1966ff.

- M. Kasper: Basque history in general. Knowledge Buchges., Darmstadt 1997, ISBN 3-89678-039-5 .

- M. Schnettger: The War of the Spanish Succession. 1701-1713 / 14. Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66173-0 .