Tibiscum

| Tibiscum Castle | |

|---|---|

| Alternative name | Τιβίσκον / Tibisco / Tivisco / Tibiscus |

| limes | Dacia |

| section | A / IV / 17 |

| Dating (occupancy) |

Traian , 2nd to 4th centuries AD |

| Type | Equestrian and cohort fort |

| unit |

a) Legio IIII Flavia Felix? b) Legio XIII Gemina? |

| size | multi-phase, rectangular system with rounded corners, a) 89 m × 107 m b) 195 m × 310 m |

| Construction |

a) wood and earth fort, b) stone fort |

| State of preservation | The fence around the second stone store in the area is recognizable as an elevation, some foundation walls of the vicus have been preserved. |

| place | Caransebeş -Jupa |

| Geographical location | 45 ° 27 '58.7 " N , 22 ° 11' 22.2" E |

| Previous |

Fort Teregova (south, A / IV / 16) Fort Färliug (west, A / II-III / 13) |

| Subsequently |

Zăvoi Castle (east, A / IV / 18) |

Tibiscum is the collective name of a Roman fort of the auxiliary troops , part of the fortress chain of the Dacian Limes ( limes Daciae , province Dacia Superior or later Dacia Apulensis ) and a municipality in the area of today's Caransebeş (Karansebesch / Karánsebes / Karanšebeš), a city in Caraș-Severin County , Banat Region in southwest Romania .

Fort, vicus and civil town are spread over an area of 27 hectares and are among the most famous archaeological sites in Romania. Lagervicus and Municipium developed in the 3rd century AD into a center for trade and goods production (especially ceramics) and thus one of the economically most important cities in the Dacian provinces. Tibiscum also played an important role in the Romanization of the local population and is considered to be one of the starting points of Christian missionary work in Dacia.

location

The camp, military vicus and civil town are located on the grounds of the Jupa, Iaz and Ciuta districts of Caransebeş, along both banks of the upper Tibisia / Temesch , a left tributary of the Danube ( Istros in Latin ). The fort area is located two kilometers southeast of Jupa on a low terrace on the left bank of the river. The site is also known under the field names "Cetate" (fortress) or "Dupa ziduri". In the area, two sides of the ramparts are still clearly recognizable as an elevation.

Surname

The ancient name ( Τιβίσκον Tibískon ) means "swampy place" comes from the Thraco - Dacian language area and is probably derived from the nature of homecooked on nearby river, lat. Tibiscus (also Tibisia, Timis ), from. In the ancient sources Tibiscum u. a. mentioned in Claudius Ptolemy's Geographica (3, 8, 10), in the Tabula Peutingeriana (Segmentum VII 4) and by the geographer of Ravenna (4, 14, 4.18). Around 1020, a place called "Dibiskos" appears in the list of the dioceses belonging to the Archdiocese of Ohrid ; it is assumed that this is the successor to the Roman city that was created in the Middle Ages. Some documents from the 15th century still mention strongly distorted variants such as B. Tyvisk or Tywsk , but then these last references to the ancient settlement disappear from the historical sources.

function

Tibiscum developed along two important highways that connected the Mösian Danube Limes with the interior of Dacia:

- Viminatium - Lederata - Arcidava - Bersobis - Tibiscum - Sarmizegetusa and

- Drobeta - Dierna - Tibiscum - Sarmizegetusa .

The garrison of the fort secured the crossing and a section of these two main connections, monitored the road traffic and the population of the Dacian settlements on the surrounding hills.

Research history

The ruins were first recognized as Roman in the 19th century by the historian Konrad Mannert (1756–1834). The first test excavations began in 1875 on the right bank of the Timis. Most of the ancient civil city is also located there. This was particularly inspired by the cleric Tivadar Ortvay (1843–1916), among other things the author of numerous historical works on the Banat. The first more precise scientific investigations were carried out between 1923 and 1924 by the archaeologist George G. Mateescu (1892-1929), lecturer at the University of Cluj . He dug in the area of the large stone fort, but the findings remained unpublished. In 1977 the excavations on the left bank of the Timisoara were declared an archaeological protection zone. From 1965 to 1989 excavations were carried out by Marius Moga, Flores Medelec, Richard Petrovszky, Maria Petrovszky, Tiberiu Bona, Doina Benea and Petru Rogoszea (camp, vicus, temple of Apollo). The north gate of Holz-Erde-Kastell II was examined by Moga in 1965. In 1982 Patrichie Puraci found in the village of Iaz, 1.5 km from the civil settlement of Tibiscum , Flur Sat Batrin (= "Old Village"), a 87 cm × 75 cm × 30 cm Roman inscription in the form of a tabula ansata , the dedication of a restored one Sanctuary to Apollo for the well-being of the emperor Septimius Severus and his sons Caracalla and Geta . While plowing the ground in the following years numerous marble fragments of another inscription with a dedication to Apollo from the time of Caracalla came to light. On the basis of these finds, Tiberiu Bona and Petru Rogoszea carried out an extensive excavation on behalf of the Museum of Caransebeş, which ultimately led to the discovery of the Temple of Apollo. In 1984, during the excavations on the western wall of the large stone camp, the remains of camp III were discovered. 1991 to 1992 one could also locate its northern side. In 2001 archaeological research was carried out again, this time in the Obreja district. An area of 20 m × 1.5 m could be examined, where again sections of the fort defense came to light. They were recognized as the remains of a ditch (fossa) and the rampart ( agger ) from the wood-earth and stone periods of the fort and were mostly from the 2nd century AD.

history

Pre-Roman times

The favorable natural conditions promoted the establishment of settlements in pre-Roman times. The area around Caransebeş has been inhabited since prehistoric times. So one came across tools from the Paleolithic (approx. 35,000 to 10,000 BC) and in the Balta Sărată also to settlements of the Vinča , Starčevo and Criș cultures from the 6th to 5th millennium BC. In addition, traces of settlement from the Middle Bronze Age (around 1600 to 1200 BC), finds from the Hallstatt period and a coin from the 4th century BC were found near Dealul Mare . Subsequently, Dacian ceramic fragments and burial mounds ( Latin tumuli ) from the 1st and 2nd centuries AD were discovered. The earliest traces of settlement by the Dacians were observed in Obreja, a village about seven kilometers away.

2nd century

Due to its geographical location, the Banat was one of the main entrances to the Dacian provinces for the Romans. After two Roman army columns under Emperor Trajan had crossed the Danube on two ship bridges (at Lederata and Dierna ) at the beginning of the First Dacian War , in the spring of 101, they advanced into the Banat. After the Battle of Tapae , which took place in the autumn of 101, the Roman invasion army, which had largely crushed the Dacian resistance in this region, set up for its first winter in enemy territory. For this purpose, numerous temporary marching camps or permanent forts were built in the Banat and neighboring Oltenia, including in Tibiscum . The early fort (camp I) was probably from 106 - d. H. after the end of the second Dacian war - and was on the right bank of the Timis. But it is also possible that a Roman base existed here before.

After Traian's death in 117, the Iazyans allied themselves with the free Dacians and attacked the Romans in several places at the same time. The provincial capital Colonia Ulpia Traiana Augusta Dacica was also badly affected in these battles. Traian's successor, Hadrian , advanced in forced marches from the Orient Provinces and brought new units with him that had been recruited in Syria, including Palmyren archers who took up their quarters in Tibiscum . For this purpose, a larger wood-earth fortification was built to replace camp I. This new fort (Camp II) extended a little further south and probably existed until 170. Its crew consisted of archers recruited in Syria. After their arrival, a military vicus was built where the families of the soldiers and, over time, numerous craftsmen and merchants settled. At the same time, a temple dedicated to Apollo was built about three kilometers away .

In the years 118–119 AD, a governor from the equestrian order , Quintus Marcius Turbo , took up his post, who had made a contribution to defending the province against the Sarmatians . Statues were erected in his honor in Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa and in Tibiscum . An inscription discovered in Caransebeş celebrates the restoration of law and order. As a result of the Iraqi invasion, the second wood-earth camp also burned down. His team barracks were then rebuilt on their old stands and consisted again without exception of wood, while the fort wall was built in stone (camp IVa). The remarkably long existence of the wood-earth camps can be explained by a longer period of peace, during which there was no need to convert the camp into stone.

During the last years of the reign of the emperor Antoninus Pius , around 158-160 AD, unrest flared up again on the western border of Dacia and he again had to lead some campaigns against the free Dacians. Major renovations were therefore carried out in Tibiscum under this emperor . Since two units were now housed here at the same time, the camp was again considerably expanded to the west and south (camp IVb). An inscription discovered in the Principia dates back to 165 and proves that the “great camp” was completed that year. The archaeological finds also support this assumption. Just outside the fort, near the northeast corner, a votive tablet and an inscription for Iupiter Optimus Maximus were discovered. They suggest that the attacks of the Marcomanni , Quadi and their allies, the free Dacians, also severely damaged Tibiscum in the years from 167 to 170 .

3rd century

With the assumption of rule by the Severan dynasty, an economic boom began for Tibiscum . Therefore, under Septimius Severus (193–211), some larger monuments were erected here. Most of the honorary inscriptions uncovered here are dedicated to his two sons Caracalla and Geta . One of the two could have raised the settlement to the status of a city of the second order, a municipality , but this can only be confirmed epigraphically for the time of Gallienus (253-260). However, repeated incursions by barbarian peoples probably caused great devastation again during this period. In the vicus one could observe clear traces of fire, especially in buildings II, VII, X. The constant raids by the barbarians, a continued weakening of the central power, the associated endemic uprisings of the army and rapid changes of rulers in the period of the soldier emperors (so-called imperial crisis of the 3rd century ) led in Dacia more and more to the decline of Roman civilization and culture such as a. shows the discovery of hoards of coins that their owners no longer have raised. Very few inscriptions in Tibiscum therefore date back to the second half of the 3rd century. After the withdrawal of the army and administration behind the Danube Limes under Aurelian , in 275 AD, the majority of the Dako novels based here apparently persisted in their city, as evidenced by traces of the reconstruction of some buildings.

4th to 5th century

The results of research so far have revealed that the city still fulfilled all the functions of a Roman municipality in the 4th century. This was mainly because it was possible to maintain close contacts with the Roman Empire. The massive emergence of late Roman coinage in the Banat testifies to an unbroken close connection between the empire and this part of the former Dacia Apulensis . Mention in the historical sources report that between the reign of Constantius Chlorus (293–306 AD) and Julian Apostata (361–363 AD ) the Romans succeeded in regaining some Dacian regions on the north bank of the Danube occupy (Dacia restituta) . This also favored the rapid spread of Christianity in the northern Danube region. Between the years 306 and 337, under the rule of Emperor Constantine I , the Romans built a new bridge over the river at Sucidava and thus regained control of the areas near the Danube in the former Dacian provinces. In addition to the Praetorium , Tibiscum was an important part of a short-lived Constantinian Limes in Dacia. Large amounts of coins from the time of Constantine were recovered in both locations. After 313, Tibiscum also became the ecclesiastical center of this region and bishopric. In 375, the Goths and Alans invaded the east of the Roman Empire and smashed the border troops on the Mösian Danube Limes (see Battle of Adrianople ). In the 5th century, the Huns devastated large parts of Dacia and Moesia . In the absence of written sources about the political events in the south-western areas of today's Romania, the exact reconstruction of the events that took place here at that time is difficult. The invasions of the Goths, Alans and Huns are likely to have had serious consequences for the inhabitants of the Dako-Roman settlements. Presumably they contributed significantly to the disappearance of the urban way of life in Dacia. After the death of King Attila in 453, his empire quickly dissolved, but it was not until Emperor Justinian I (527-565) that the Romans regained control of the lower Danube for a short time.

6th to 12th century

In 558 the Avars , led by Khan Baian , invaded in 559 the Kutrigurs with their allies, the Slavs and Bulgarians , in Dacia and Moesia. In 593, the Byzantine generals Petros and Priskos carried out another campaign against the Slavs and Avars on the Danube. In 602 the last forts occupied by the Byzantines in the Danube region fell into the hands of the Slavs. However, the first archaeological finds from Caransebeş, which prove the existence of settlements of the Slavs or Avars, date from the 8th and 9th centuries. A document from the time of Emperor Basil II (976-1025) mentions an episcopal church in Dibiskos around 1020 , perhaps identical to the ancient Tibiscum . From the 11th century, the Hungarians in particular settled in the area around Caransebeş, which soon became one of their centers in the Banat. In the 12th century, the former Roman settlement was finally transformed into a medieval town, the core area of which was around the fortress, which was first mentioned in 1289.

Fort

During the excavations in the 20th century, several construction phases could be identified:

Wood and earth fort I to III

Fort I: The early wood and earth fort was located in the NE corner of the later stone fort (Fort IVb) and was built during the occupation period between 101 and 106 AD. Its traces were only discovered during the most recent excavations. The remains were about 1.80 to 2.00 m deep below today's ground level. It was a rectangular complex, the exact extent of which is not exactly known. Its fence was 6 m wide and 1.20 m high, on the southern section the remains of two trenches were found 2.25 m apart (10–2.20 m × 2.25 m and 2 m × 2.10 m) . Remains of the earth wall (agger) could still be seen behind the trenches .

Fort II: The fortification soon had to be expanded and was extended considerably over the wall of Fort I. This was leveled beforehand so that the floor level of the new warehouse rose by 25–30 cm. Its dimensions were 110 × 101 m, it covered an area of 1.11 hectares. According to the traces of the remains of the palisade in the trench, the camp was destroyed by fire. The traces of fire date back to around 118 AD and were probably a result of the defensive battles against the Sarmatians . The earth wall was 5 m wide and was surrounded by two defensive trenches - the first 2.75 m wide and 0.75 m deep, the second 3.50 m wide and 1.25 m deep.

On each side of the camp there was a gate flanked by two towers. The eastern one was 48.80 m from the north-eastern corner of the camp. Its square towers were made of wood. They each stood on four wooden beams (0.25 × 0.25 m), the walls were made of rod weave with straw mud. On the outside of the wall, the beam holes could still be detected. The dimensions of the towers were 2.40 × 2.40 m. The gate was 3.90 m wide. In 1984 the somewhat smaller southern camp gate was also exposed; its flank towers were also square (2.55 × 2.55 m), while the gate itself had a width of 3.25 m. Since the north gate remained in function during the entire period of use of the military base, it was rebuilt several times, so that its original appearance could only be reconstructed with great difficulty. The gate width is three meters, the flank towers were constructed somewhat differently compared to the other gate towers. In 1987 the north-western corner tower measuring 2.40 × 2.40 m was uncovered. It was also square, stood on four wooden beams, and had walls made of rod weave and straw clay.

The inner buildings of Camps I and II were made entirely of wood. The team barracks were presumably set up in a west-east direction, along the axis of the main camp street, the via principalis . On the inside of the wall one could also see a section of the surrounding wall road, the via sagularis . It had a gravel surface and was 3 m to 3.10 m wide.

Fort III: To the south of the large stone fort there was another wood and earth fort. It probably dates from the middle of the 2nd century and covered an area of 89 m × 107 m. The south and east gates were flanked with rectangular gate towers. The Palmyren archers were probably housed here.

Steinkastell IVa (small camp)

After the unrestricted Roman rule over the province was restored, the stone fort was rebuilt. A stone wall with a width of 3.25 m was blinded to the outside of the old earth wall. The foundation consisted of two layers of river rubble over which a layer of mortar had been poured. The wall itself was built from cut limestone blocks. The gate towers were also rebuilt in stone and now measured 4.20 m × 4.20 m, while the width of the passage remained unchanged. Inside the warehouse, the buildings were rebuilt from wood exactly at their old locations. Although probes have been used to search for the Principia, their location has not yet been pinpointed. They were presumably oriented to the south.

Steinkastell IVb (large warehouse)

The so-called "large camp" was created by considerably extending the southern and western walls of camp IVa. It was designed by its builders in the classic manner of the early and middle Imperial Era as a trapezoidal, slightly northwest-oriented, probably 195 m × 310 m large complex with rounded corners. Due to the complete destruction of the south side, its exact scope could no longer be precisely determined. The western section of the fort wall also included the area of Fort III, which led to a significant deviation from the otherwise usual rectangular shape. However, the high groundwater level also made it necessary to work on securing the foundations. In the 3rd century, the fort was completely renovated under Gallienus .

Defense, gates and towers

The inner wall of the new camp was 5.50 m wide. On its outside, a fence standing on a foundation made of river rubble was raised again. The 1.50 m wide enclosing wall was constructed using the opus incertum technique and consisted of mortarized rubble stones; inscriptions from the time of Emperor Gordianus (238–244) were also built into it .

The west gate with a 3.90 m wide passage and its two square, slightly protruding flank towers (7 m × 5.80 m) could be proven. The 7.50 m wide main gate (porta praetoria) in the east with two 3.90 m wide passages separated by a central pillar (spina) , its flank towers consisted of massive limestone blocks. Its internal dimensions were 5.10 m × 3.40 m. A sewer ran through the middle of the southern passage. In the 3rd century, the insides of the gate towers were repaired again with rubble stones. The north gate of Camp IVa was included in the new fort and its location was not changed. What initially appeared to the archaeologists as the foundation of a barrier wall later turned out to be a gate threshold, which had been created by adapting to the higher ground level of camp IVa. The internal dimensions of its flank towers were 3.10 m × 3.10 m, the width of the passage 3.25 m. The south gate is no longer preserved. The corners of the camp were probably also reinforced by trapezoidal towers set on the inside.

Interior development

The buildings inside the camp could be dated to the 2nd century. During the excavations in 1964–1975, Marius Moga uncovered three buildings in the northeast corner of the camp. The first was found about 6.40 m from the fort wall (No. I). It was square in shape, measured 28.80 mx 6.80 m and had two rooms. The excavator suspected that the building was a Palmyren officers' quarters from the time of Septimius Severus. The second building was two meters west of this officers' house. It had a north-south orientation and was divided inside by three rooms (No. II). Originally, however, there was probably only one room - enclosed by an apse. What it was used for could not be clarified. It could either have been a weapons depot or an administrative building. The third building (34 × 6.40 m) comprised a total of seven rooms and appears to have partially served as a team barrack (No. IV). Some of these buildings were equipped with hypocaust heating and may also have had cultic functions. This part of the camp was probably created by the Palmyrenian soldiers as a forum castrensis in the Hellenistic-Oriental tradition. Buildings I, II and IV (north end) presumably acted as principia. In the praetentura of the camp one came across the remains of the camp thermal bath, which Mateescu was able to uncover in part in 1924. At the rear of the Principia a section of the 4.50 m wide via Decumana could be observed.

Principia:

Of the buildings inside the camp, the three-phase command building in particular was examined more closely. The archaeologists found a rectangular building (35 m × 45 m) that was oriented to the east. It was entered through a roofed, columnar courtyard (atrium) measuring 15 mx 27 m , which was flanked by further rooms on the north and south sides. Four column bases (1.00 m × 0.80 m) each sat on two parallel stone foundations, about 2.40 m away from the adjacent rooms. In the second construction phase, the entrance to the inner courtyard was narrowed. Along the axes that corresponded to the gate pillars, three square stone bases were set up. They probably served as a base for altars or statues. The pillars supported the roofing of the two connecting corridors to the 8 m × 45 m transverse hall (basilica) . An honorary inscription found here, which the cohors I Sagittariorum dedicated to the emperor Mark Aurel in 165 , is an indication that at this point in time the principia and thus - probably - the camp itself had already been largely completed. In contrast to the inner courtyard, the basilica's floor was about 20 to 30 cm higher. The thresholds of these rooms consisted of large limestone blocks on which traces of depressions could be seen, which probably served to anchor a metal barrier. On the west side there were a total of five rooms, in the center the rectangular flag sanctuary (aedes) protruding slightly to the west , in which the standard symbols and an emperor statue were kept. Under his floor was a cellar in which the payroll of the crew was kept. On the north and south sides of the transverse hall there were two seven by ten meter chambers, possibly for the storage of weapons (armamentaria) . The commandant's office was located in the two rooms to the left of the aedes . To the right of this were the rooms of the standard bearers (signifer) who administered the troops' finances. These too were probably once closed with an iron grille. In the last, the westernmost room, there was an altar made of bricks, which was sunk a little in the screed of the floor. Remnants of animal bones and ashes were found scattered on it and in the rest of the room.

garrison

Together with Porolissum , Micia , Bologa, Borosneu Mare and Romula, Tibiscum is one of the forts with the largest number of garrisons in Dacia. Probably two units each remained permanently stationed here until the end of Roman rule.

| Time position | Troop name | comment | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2nd century AD |

Legio IIII Flavia Felix ? (the fourth Flavian Legion, the lucky one) Legio XIII Gemina ? (the thirteenth twin legion) |

The first occupying force of the fort has remained unknown. Possibly these were vexillations from these two legions, the fourth legion was stationed nearby, in Sarmizegetusa. The presence of members of these troop units is only known from brick stamp finds; they probably only provided the construction teams for the fort. | |

| 2nd century AD |

Cohors I saggitariorum millaria equitata (the first cohort of mounted archers, 1000 strong) |

It was the first auxiliary unit whose presence in Tibiscum is epigraphically documented by brick stamps and, above all, by an honorary inscription for Marcus Aurelius donated by it - from the year 165. Towards the end of the 2nd century the troops were withdrawn and moved to the Drobeta fort . | |

| 2nd to 3rd century AD |

Numerus Palmyrenorum Tibiscensium (a flock of Palmyrenians in Tibiscum ) |

The department was transferred from Syria to Dacia in the wake of the war events of 118 AD. Two military diplomas from 126 discovered in Tibiscum prove the presence of the Palmyrenians in the camp. Another evidence is a consecration altar from the 3rd century discovered in 2004 in a warehouse (No. IV) , which was dedicated to the goddess Minerva by the unit's paymaster / supply officer ( Actuarius ), Valerius Rufinus .

Most of the Dacian dedicatory inscriptions for Minerva were made on behalf of Actarians. The number was subsequently also mentioned in a grave inscription from AD 159 to 160. A badly damaged marble inscription from the 3rd century AD, discovered by Marius Moga in the same building, names this unit:

|

|

| 2nd to 3rd century AD |

Cohors I Vindelicorum civium Romanorum milliaria equitata (the first partially mounted cohort of the Vindeliker , Roman citizens, 1000 strong) |

The auxiliary cohort, originally from the province of Raetia , probably came from the Arcidava camp to Tibiscum and provided the occupation force here from the late 2nd century onwards. A military diploma from the year 157 discovered in Tibiscum , which was issued to a veteran of the Raetian cohort, is the first indication of the presence of this troop at this garrison location. The unit rebuilt the fort after the great devastation in the 3rd century. Two inscriptions found in the Temple of Apollo attest to its renovation in the years 202-204, one of which was carried out by order of its commanding officer, the Tribune Septimius Diomedes.

A few years later, 212–215 AD, the troops, which were then led by the Tribune Publius Aelius Gemellus, consecrated Apollo as the keeper of Emperor Caracalla. The Raetian cohort stayed here until the Romans withdrew from Dacia under Aurelian (271–275 AD). |

|

| 2nd to 3rd century AD |

Vexillatio Africae et Mauretaniae or Numerus Maurorum Tibiscensium (a flag of Africans and Moors and a group of Moors in Tibiscum ) |

These African and Moorish soldiers were transferred to Dacia around the middle of the 2nd century. The numerus Maurorum Tibiscensium later emerged from their ranks . |

Bronze bust of an African ( Museum Carnuntinum )

|

Vicus

An extensive camp village ( vicus ) was found north of the fort . The settlement was probably created at the same time as the wood-earth warehouse in the first half of the 2nd century. The flourishing economy, the influx of relatives of soldiers and craftsmen and the close trade relations with the neighboring provinces soon gave the military settlement a small-town character. Although the Timiş destroyed a significant part of the area in the course of time, it is believed that the vicus covered an area of about twelve hectares in its heyday. It was severely damaged by fires several times, the first time probably around 118 AD when the Sarmatians invaded it and then again in 158/159 AD, but then quickly rebuilt by its residents.

In the vicus, the influence of military architecture on the buildings was particularly evident. The arrangement of the buildings indicates that the area was first measured and divided into plots before it was assigned to the new settlers for development. The majority of the houses had an elongated, square shape ( strip houses ), a type of construction that could be found all over the Limes. Presumably, vegetable and fruit gardens were also laid out in their immediate vicinity. The buildings were mainly lined up along both sides of the main thoroughfares, which also served as decumanus maximus . Some of them also had small porticos ( porticus ) on their street front . Moga uncovered a total of eleven buildings during his excavations, but only one of them, Building II, has so far been fully investigated. In building X, handicrafts could be identified for the first time in a Dacian vicus. These were ceramic, glass and jewelry workshops.

Some changes in the construction scheme of the vicus could also be related to the stationing of a new occupation force. As the buildings were restored several times, their floor plans were also changed. The width of the buildings varies between 9 m and 14.40 m. Towards the end of Hadrian's reign, most of the buildings were completely demolished and rebuilt in stone. The most representative structure discovered so far on the site of the military settlement is building VII, where u. a. a marble lararium was found. Some houses (II, VII, X) were also equipped with hypocaust heating.

After the Roman army and administration had withdrawn between 271 and 275, it was noteworthy that no fire or other traces of destruction could be discovered from this time shift that could be brought into connection with this withdrawal, neither in the camp nor in the civilian settlements. In buildings II, III, VII, VIII and X, only a few changes to the interior were found. This involves the installation of new walls made of river boulders that were placed directly on a layer of rubble without a foundation. They were only slightly bonded with mortar and were 0.50 m wide. In the newly created chambers, the inventory was evidently very simple, mostly only fragments of inferior provincial ceramics were found.

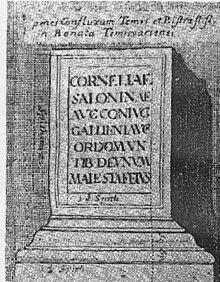

Municipium

In the 17th century, the explorer Luigi Ferdinando Marsigli reported on the discovery of an honorary inscription dedicated to the Salonina, the wife of Emperor Gallienus, by the council (ordo municipii) of the municipium Tibiscensium . It was discovered near the confluence of the Bistra and Timi rivers. This was a first indication that the civil town was on the right bank of the Timis. The influx of numerous veterans, family members of the soldiers, merchants and craftsmen in Tibiscum contributed to the rapid development of a second-rate city, a municipality . The granting of municipal rights was usually preceded by a long, successful development of the economy. Tibiscum, like some other cities in Dacia, may have been granted municipal status under Septimius Severus or his successor Caracalla. Epigraphically, however, the municipal rank of the civil settlement is only confirmed by the cited inscription by Gallienus (260–268 AD). This late urban elevation marked the end of Roman urbanization in Dacia.

population

As in other Roman provinces, it was mainly the veterans, soldiers and new settlers who contributed to the rapid Romanization of the local population. Of the more than 90 inscriptions discovered in Tibiscum so far , 60 are grave inscriptions. They prove u. a. the presence of members of different ethnic groups, especially those who formed the occupying forces of the camp, such as B. Vindelicier from Raetia , Palmyren from Syria and Moors from North Africa. Naturally, the indigenous Dacians were particularly numerous, both in the camp and in the civilian settlement. Their presence is documented mainly through Dacian ceramics. Direct evidence of the level of education of the residents in Tibiscum is rare. However, a large number of bone or bronze writing utensils were found. In addition, bricks and ceramic fragments with incised letters, probably attempts at writing to learn the alphabet, were recovered.

Economic life

Trade was one of the main sources of wealth for the people of Tibiscum . The large number of Roman coins from the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD that were found here shows extensive trading activity, which however weakened noticeably in the second half of the 3rd century. Two of the previously discovered workshops (for ceramics and glass production) continued to work in the post-Aurelian era. The continued existence of economic life during the 3rd to 4th centuries is primarily evidenced by coin finds. Apart from the hoard found consisting of 971 coins, which was discovered in 1925, more than 50 coins were also found in the area of the civil settlement. This is proof of the continued trade relations with Rome, although the movement of goods had probably decreased significantly. In the middle of the 4th century in particular, coin circulation seems to have increased somewhat again. But already towards the end of this century (approx. 370–380 AD) it shows a downward tendency to come to a complete standstill a little later, probably a consequence of the devastating defeat of the Romans at the battle of Adrianople (378) .

Agriculture: The fertility of the area around Tibiscum favored the development of a prosperous agriculture, as the occupation of the Romans also introduced new cultivation methods. In the course of archaeological research, several villae rusticae were discovered near the fort . B. at Caransebeş, Mahala, Campul lui Cornean and Iaz. Their owners were probably Roman colonists or veterans who had settled here, as the military administration presumably gave them the best land to cultivate. What exactly was planted at the time has not been clarified, as there are still no conclusive findings in this regard. In any case, numerous animal bones are evidence of flourishing livestock farming, including mainly cattle, sheep, and more rarely pigs.

Ceramic production: Ceramic production was an important economic branch. Mainly building materials, clay pipes, vessels, oil lamps and statuettes (Venus terracottas) were produced. Several army-run ceramic product workshops have also been identified in Tibiscum . For the time being, many are only known by their stamps. Some of these stamps such as ARF, VAM, PCH could not be assigned satisfactorily. It is uncertain whether they come from military or civilian workshops. The name Marcus Syrus, probably a local manufacturer, could still be read on an amphora handle. The popular name Severus was found on the edge of a mortuary . A certain Aurelius (stamp: AVRELVS F [ECIT]) was a leader in the manufacture of clay lamps.

The process of gradual amalgamation of the native population and occupation soldiers is particularly reflected in the handcrafted Dacian ceramics. Two large pottery workshops, one from the 2nd century and the other from the 3rd or 4th century AD, were uncovered on the area of the civil settlement. Various earthenware for local needs was produced here, from common ceramics to large quantities of terra sigillata imitations. Of the late Roman ceramic pieces, 15 clay lamps with eagle handles found in Tibiscum , which were made during the 3rd or 4th century AD, stand out.

Metal goods production: The vast majority of local metal products came largely from local workshops, housed in simple wooden frame structures. A large number of imported goods were also found in Tibiscum . The locally produced bronze statuettes are only very simple. They are likely copies of pieces imported from Italy. About 25 m north of the camp, a blacksmith's shop was found which could be dated to the first half of the 2nd century. One of them (Workshop II) could have been operated by the military and mainly produced equipment such as B. buckles, fittings, harness, etc. In a recently discovered workshop (III) was jewelry such. B. made a disc brooch with enamel decoration, which could be dated to the Severan period. Since the workshop, which is housed in a wooden building, had been destroyed by fire, the archaeologists were able to recover an almost complete inventory of tools, including small melting pots in which traces of gold could even be found. Subsequently, further workshops for processing precious metals such as bronze, silver and gold were found. Presumably, the ancient city in this part of the province was a center of jewelry production.

Glass production: Tibiscum was also an important center of Dacian glass production. To the west of Buildings I, II, VII of the civil settlement, there were workshops that mainly produced containers and jewelry (glass beads). Production could be maintained well into the 4th century.

Stone processing: There must also have been stone cutting companies in Tibiscum , although they have not yet been discovered or their function has not been correctly assigned. Some of the pieces were probably made in Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa , because some monument fragments clearly show similarities with specimens found in Sarmizegetusa. Stone god sculptures are only weakly represented in Tibiscum . Most often there are votive reliefs with depictions of Jupiter, Diana and Mercury.

Cult and religion

In the religious life of the inhabitants of Tibiscum , the worship of the Roman deities played a major role. Numerous inscriptions were dedicated to them:

- Jupiter (4),

- Apollo 3),

- Mars (1),

- Liber Father (2),

- Silvanus (1),

- Nemesis (1?).

From a dedicatory inscription for Jupiter Optimus Maximus , the name of a resident, Iulius Valentinus, is also known epigraphically.

Otherwise, the protective gods from the home provinces of the fort occupation had a certain importance for the population. B. from Palmyra the deities Malakbel and Bal .

A temple of Apollo was uncovered three kilometers east of the fort, in which there were two inscriptions dedicated to the Severan emperors, which report on the restoration or renovation of the building (see section Garrison). So far it is the only (but only partially) uncovered temple in Tibiscum . Its relatively simple floor plan is similar to that of the so-called "Temple of the Moorish Gods" in Micia . It is also assumed that building III in the vicus also served as a sanctuary or place of worship, as an oversized statue head of Jupiter and a smaller fragment of a votive column were found here.

Limes course (road post) between Fort Fărliug and Fort Orăştioria de Sus

The crews of the forts listed below probably primarily had to monitor the road connection Lederata - Alba Iulia .

| Surname | Description / condition | Illustration |

|---|---|---|

| Zăvoi Castle ( Acmonia ?) |

The fort is located in the Zăvoi commune, Caras-Severin district. The wood-earth camp built in the early occupation secured the road to the pass crossing from Porțile de Fier ale Transilvaniei (Iron Gate of Transylvania), which separates today's Banat from Transylvania. After the consolidation of Roman rule in Dacia, it was abandoned and abandoned around 106-107 AD. Its area is located on a terrace protected from the periodic floods of the Bistra, directly below the center of Zăvoi, field name "Cetate" (= fortress). The fort has not been archaeologically investigated; the fence can still be seen as a significant increase in the terrain, but has been partially destroyed by residential buildings and roads. The camp was aligned exactly to the four cardinal points and had a square floor plan, which covered an area of 336 m × 336 m. There is no reliable information about the units that were garrisoned here. It is possible that the occupation was provided by the legio I Minervia in the early days of the fort or that they may have built the fort. A brick stamp of the first cohort of archers - which stood in Tibiscum - suggests that a vexillation of this troop could also have been temporarily stationed here. |

|

| Sarmizegetusa legionary camp | The fort is located in the municipality of Sarmizegetusa in the district of Hunedoara / Haţeg, about eight kilometers north of the important pass of Porile de Fir ale Transilvaniei.

In pre-Roman times, the place was inhabited by Dacians and served as a royal residence. The site was only examined superficially, some excavation campaigns took place between 1970 and 1985. The excavations confirmed the previous assumption that a military base must have existed here even before the founding of the colonia in 107 AD. Its area ("Cetate") on the right bank of the Apa Orasului River is now built over by the town center. The camp was built by the Roman surveyors, well protected against flooding, on a low terrace protruding against the heather . The wall, which is partially covered by modern residential buildings, can still be seen on all sides. The fort was used from 102 to 107 AD and was occupied by the legio IIII Flavia Felix , which is attested mainly by brick stamps. After the legion withdrew, the camp was built over at the turn of the 2nd to the 3rd century by one of the metropolises of the Roman Dacia, the Colonia Ulpia Traiana Augusta Dacica Sarmizegetusa , which in the early days was still based on the expansion of the former camp, because the fence was not leveled. The warehouse, initially built using a wood-earth construction method, was rectangular with rounded corners, 546 m × 415 m in size, and precisely aligned with the four cardinal points. The 1.60 m wide wall was reinforced at its corners with trapezoidal towers attached to the inside; in the late Raian or Hadrian times a stone wall made of worked stone blocks (opus quadratum) was placed in front of it. It was also surrounded by two trenches, one 7 m wide and 2.50 m deep, the other 6 m wide and 1.50 m deep. Of the wooden interior structures, only the principia are known. They consisted of a columned forecourt, a transverse hall (basilica) and a flag sanctuary (aedes) , which was flanked on both sides by two rooms (officium) . |

Tourist notices

An archaeological protection zone and a permanent exhibition of Roman finds have been set up on the left bank of Temes. You are at the northern exit of Jupa, about 250 meters from the national road. Finds from Tibiscum are now in the Muzeul Banatului in Timișoara and in the Muzeul de Etnografic si Istorie Localä in Caransebeş (a former barracks built in 1754) with a collection of over 48,000 exhibits.

Monument protection

The archaeological site is protected as a historical monument under Law No. 422 of 2001 and is registered with the LMI code CS-IsA-10805 on the National List of Historic Monuments (Lista Monumentelor Istorice). Responsible is the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage (Ministerul Culturii şi Patrimoniului Naţional), in particular the General Directorate for National Cultural Heritage, the Department of Fine Arts and the National Commission for Historical Monuments and other institutions subordinate to the Ministry. Unauthorized excavations and the export of ancient objects are prohibited in Romania.

See also

literature

- Max Fluß : Tibiscum. In: Paulys Realencyclopadie der classischen Antiquity Science (RE). Volume VI A, 1, Stuttgart 1936, Col. 813 f.

- Alexandru Borza: Banatul ín timpul Romanilor [The Banat in Roman times] . (= Monografii despre raporturile dintre Italieni şi Români 4). Varzi, Timişoara 1943.

- Dumitru Tudor: Tabula Imperii Romani (TIR): Bucarest. Drobeta-Romula-Sucidava. Académie de la République Socialiste de Roumanie, Bucharest 1969 (parts of sheets K-34, K-35, L-34, L-35), here: TIR L 34.

- Nicolae Gudea : The Defense System of the Roman Dacien. In: Saalburg yearbook. 31, 1974, pp. 41-49.

- Nicolae Gudea: Limesul Daciei romanc de la Traianus la Aurelianus. In: Acta Musei Porolissensis. 1, 1977, pp. 97-113.

- Ion I. Russu : Inscripţiile antice din Dacia şi Scythia Minor. Vol. 3, 1, Bucharest 1977, pp. 145-234.

- Ioan Piso, Doina Benea: The military diploma of Drobeta In: Journal of papyrology and epigraphy . 56, 1984, pp. 263-295. Revised reprint in: Ioan Piso: On the northern border of the Roman Empire. Selected studies (1972–2003). Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart 2005, ISBN 3-515-08729-X , pp. 109-142.

- Ioan Piso, Petru Rogozea: An Apollo sanctuary near Tibiscum. In: Journal of Papyrology and Epigraphy. 58, 1985, pp. 211-218.

- Adrian Ardeţ: Le municipe romain de Tibiscum. In: La politique edilitaire dans les provinces de l'empire romaine. Actes du Ier Colloque Romano-Suisse, Deva 1991. Cluj-Napoca 1993, pp. 83-89.

- Adrian Ardeţ: Limitele oraşului roman Tibiscum. In: Studii de Istorie a Transilvaniei. Cluj 1994, pp. 61-65.

- Doina Benea, Petru Bona: Tibiscum. Ed. Museion, Bucharest 1994, ISBN 973-95902-6-8 (with a summary in German).

- Doina Benea: Oraşul antic Tibiscum. Consideraţii istorice şi arheologice. In: Apulum. 32, 1995, pp. 159-172.

- Nicolae Gudea: The Dacian Limes. Materials on its story. In: Yearbook of the Roman-Germanic Central Museum Mainz. 44, 2, 1997, pp. 27-28 PDF .

- Jan Burian: Tibiscum. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 12/1, Metzler, Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 3-476-01482-7 , Sp. 536.

- Doina Benea: The economic activity in the village branches between Theiss, Marosch and Danube. In: Studia Antiqua et Archaeologica. 9, 2003, pp. 299-318 PDF .

- Ardrian Ardeţ, Lucia Carmen Ardeţ: Tibiscum. Aşezările novels. Ed. Nereami Napocae, Cluj-Napoca 2004. ISBN 973-7951-58-1

- Nicolae Gudea, Thomas Lobüscher: Dacia, a Roman province between the Carpathian Mountains and the Black Sea (= Orbis Provinciarum ; Zabern's illustrated books on archeology ). Zabern, Mainz 2006, ISBN 3-8053-3415-X .

- Călin Timoc: New inscriptions from the Roman fort of Tibiscum. In: Analele Banatului, SN, Arheology - Istrorie. 14, 1, 2006, pp. 277-282 PDF .

Web links

Remarks

- ^ Route / section / fort number (based on Nicolae Gudea , 1997).

- ^ Translation: "For Minerva and the Genius of the Numerus Palmyrenorum Tibiscensium, by Valerius Rufinus, Actarius".

- ↑ Translation: "For Apollo, for the good of our Messrs. Severus, Antoninus and Caesar Geta, under Octavius Julianus, consular governor of the Dacian provinces for the third time, Septimius Diomedes, tribune of the 1st partially mounted 1000-strong Vindeliker cohort of Roman citizens, has this." Have the temple (?) Restored ”.

- ↑ List is from SW to NE.

- ↑ Gudea / Lobüscher 2006, p. 35.

- ↑ a b Ioan Piso, Petru Rogozea: An Apollo sanctuary near Tibiscum. In: Journal of Papyrology and Epigraphy. 58, 1985, pp. 211-214, No. 1 = AE 1987, 848 .

- ↑ a b Ioan Piso, Petru Rogozea: An Apollo sanctuary near Tibiscum. In: Journal of Papyrology and Epigraphy. 58, 1985, pp. 214-218, No. 2 = AE 1987, 849 .

- ↑ Gudea / Lobüscher 2006, p. 23.

- ↑ Gudea / Lobüscher 2006, p. 35.

- ↑ Gudea / Lobüscher 2006, p. 33.

- ↑ Gudea / Lobüscher 2006, p. 34.

- ↑ Gudea / Lobüscher 2006, p. 100.

- ↑ Doina Benea: The camp of Praetorium (Mehadia) in late Roman times. In: Pontica. 40, 2009, p. 344 PDF ; Gudea / Lobüscher 2006, p. 99.

- ↑ Timoc 2006, p. 279.

- ↑ Gudea / Lobhüscher 2006, p. 40.

- ↑ Gudea / Lobüscher 2006, p. 37.

- ^ AE 2006, 1175 .

- ↑ Timoc 2006, p. 278.

- ↑ Timoc 2006, pp. 278-279.

- ↑ Piso 2005, p. 133.

- ↑ CIL III, 1550 : Corneliae / Saloninae / Au [g (ustae)] coniugi / Gallieni Aug (usti) n (ostri) / ordo mun (icipii) / Tib (iscensium) dev (otus) num (ini) / maiesta [ t (ique)] eius.

- ↑ Gudea / Lobüscher 2006, p. 24.

- ↑ Gudea / Lobüscher 2006, p. 101

- ↑ Gudea / Lobüscher 2006, p. 40.

- ↑ Doina Benea, Richard Petrovszky: workshops on metalworking in Tibiscum in the second u. 3rd century AD In: Germania 65, 1, 1987, pp. 226-239.

- ↑ Doina Benea: The Roman pearl workshops from Tibiscum / Atelierele Romane de mărgele de la Tibiscum. Editura Excelsior Art, Timişoara 2004, ISBN 973-592-113-8 ; Gudea / Lobüscher 2006, pp. 45-46. 100.

- ↑ CIL 3, 7997 .

- ↑ Ioan Piso, Petru Rogozea: An Apollo sanctuary near Tibiscum. In: Journal of Papyrology and Epigraphy. 58, 1985, pp. 211-218; Benea / Bona 1994, pp. 108-109; Adriana Rusu-Pescaru, Dorin Alicu: Templele romane din Dacia. Vol. 1. Deva 2000, ISBN 973-0-00645-8 , pp. 42–49, pp. 168–169, plan 10 (excavation plan).

- ↑ Gudea 1997, pp. 34-37.

- ↑ Jan Burian: Sarmizegetusa. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 11, Metzler, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-476-01481-9 , column 85 f.

- ↑ Gudea / Lobüscher 2006, p. 26.

- ↑ Gudea / Lobüscher 2006, p. 24.

- ↑ List of historical monuments on the website of the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage .