Cuban Missile Crisis

| date | October 14, 1962 to October 28, 1962 |

|---|---|

| place | Cuba |

| Casus Belli | Deployment of Soviet missiles in Cuba in response to American missiles already stationed west and south of the USSR |

| output | Compromise solution after negotiations with subsequent blockade |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

| Commander | |

| losses | |

|

1 aircraft shot down |

no |

The Cuban Missile Crisis (in Russia and in GDR parlance also known as the “Caribbean Crisis”, in Cuba as the “October Crisis”) in October 1962 was a confrontation between the United States of America and the USSR resulting from the deployment of US medium-range missiles of the Jupiter type on a NATO base in Turkey and the subsequent decision to station Soviet medium-range missiles in Cuba . While the ship was being transported to Cuba, the American government under President John F. Kennedy threatened to use nuclear weapons if necessary to prevent the station from being stationed in Cuba. The actual crisis lasted 13 days. This was followed by a reorganization of international relations. With the Cuban Missile Crisis, the Cold War took on a new dimension. Both superpowers came closest to a direct military confrontation during this crisis. For the first time, a broad public became aware of the enormous dangers of a possible nuclear war .

prehistory

The USA and the USSR emerged as world powers from the Second World War . They stood for two opposing economic systems and ideologies. With the development of more and more new weapon technologies, an arms race began around the early 1950s .

Before the introduction of the first ICBMs , long-range bombers were used as a means of launching nuclear weapons . Standard models were the aircraft type B-52 in the USA and the Tu-95 in the Soviet Union. In the 1950s, the US, with the Strategic Air Command bomber fleet, was far superior to its adversary in terms of both the number of nuclear weapons and the means of delivery. When the Soviet Union presented the world's first functional ICBM in 1957, there was a mood of alarm in the West ( Sputnik shock ). However, the long advance warning times made a surprise attack with both aircraft and missiles almost impossible.

To avoid these warning times, missiles had to be installed closer to the target. In 1958, the Soviet Union began to deploy R5 medium-range nuclear missiles in the GDR , which were directed against targets in Western Europe, especially the Federal Republic of Germany . However, they were unexpectedly relocated to Kaliningrad in 1959 . The next stage of the arms race followed that same year. These reached the USA in January 1959 with the installation of nuclear medium-range Thor- type missiles in England and Jupiter missiles in Apulia (southern Italy) and near Izmir in Turkey. Even a nuclear first strike was not ruled out, which was supposed to destroy the enemy through the massive use of nuclear weapons and make any retaliation impossible. In the early 1960s, it was possible that both superpowers each other from home soil from having nuclear-tipped intercontinental ballistic missiles could shoot.

The Soviet-Chinese resentment in the 1950s and Khrushchev's failed attempt to revoke the city's four-power status in the Berlin crisis of November 1958 weakened the Soviet position in the Cold War. The situation changed when, in January 1959, the guerrillas under Fidel Castro overthrew the Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista . Castro formed a revolutionary government in which various opposition groups were initially represented, including the communists that were soon to be favored . Batista had long been supported by the USA and Castro also campaigned in 1959 to maintain good relations. For the US government, which remained skeptical because of Castro's alliance with the communists, he was out of the question as a partner. US President Eisenhower turned down offers of economic aid to Cuba during this phase. The American government later supported the Cuban opposition and also terrorist groups that carried out attacks and acts of sabotage . Even assassinations against Castro were attempted and the faking of acts of terrorism and military incidents ( Operation Northwoods ) as a pretext for invading Cuba was considered.

The USSR observed this development carefully and established diplomatic relations with Cuba in May 1960. With the economically strong USSR behind him, Castro hoped to become a role model for national independence in Latin America. The USA viewed this as an unacceptable attempt to spread communism in Central and South America .

After remunerationless nationalization of agricultural land, banks and refineries from US-owned in Cuba, the US government banned in October 1960 by decree , oil export to Cuba; at the same time it banned all imports from Cuba. The Soviet Politburo then promised the Castro government economic and military support. These commitments were later as an opportunity for those with concealed support of the CIA by Cuban exiles executed Bay of Pigs Invasion of April 1961 which ended for the attackers in a fiasco. In the same year the USA worked out a secret program to sabotage and infiltrate Cuba ( Operation Mongoose ).

The alliance between the Soviet Union and Cuba was beneficial for both states. The USSR hoped to make up for its strategic deficit with the US if the enemy territory could be reached by medium-range missiles, and Cuba viewed the Soviet Union as the most important trading partner and protecting power that the Castro government could protect from violent US influence.

Immediate history

From 1959 onwards, the USA stationed one squadron with 25 squadrons in Italy and two squadrons in Turkey with 25 nuclear-armed medium-range Jupiter missiles aimed at the USSR.

On October 26, 1960, the United States started U-2 reconnaissance flights over Cuba from Laughlin Air Force Base in Texas . On September 5, 1961, the first images of anti-aircraft missiles of the type S-75 and of fighter aircraft of the type MiG-21 Fishbed were made.

In April 1962, the American Thor and Jupiter nuclear missiles were made operational in Turkey.

In addition, US submarines with Polaris nuclear missiles were sailing the seas . These submarine-launched ballistic missiles could also be fired under water and were accordingly difficult to hit. At the time, the Soviet Union had nothing of equal value to counter.

From July 10, 1962, the USSR clandestinely deployed military under the code name Operation Anadyr in Cuba. The Soviet navy and merchant fleet transported over 42,000 soldiers and 230,000 tons of equipment to Cuba with 183 trips by 86 ships, including 40 R-12 and 24 R-14 medium-range missiles with associated nuclear warheads of 0.65 MT (R-12) and 1.65 MT (R-14). For comparison: the Fat Man dropped through Nagasaki had 0.024 MT. These missiles were apparently not only installed to protect Cuba, but primarily served to build up a military threat potential that was intended to compensate for the weakness of the Soviet arsenal of ICBMs .

The first intelligence information in the western camp about the construction of attackable Soviet missile bases in Cuba most likely came from the German Federal Intelligence Service : The BND had had information about the expansion of the bases for medium-range missiles since June 1962 and assessed this as a dangerous provocation of the USA by the Soviet Union.

On 5 and 29 August 1962, the CIA corresponding notes went and saw in photos of a reconnaissance aircraft of the type U-2 first time in the province of Pinar del Río launchers for Soviet air defense missiles.

On September 8, 1962, the Soviet cargo ship Omsk docked in Havana with a load of SS-4 medium-range missiles, but did not bring the cargo ashore. On September 15, 1962, US reconnaissance photos were taken in the Atlantic of the Soviet cargo ship Poltava , which was loaded with military equipment and was en route to Cuba.

Timeline of the crisis in October 1962

The highlights of the crisis in October 1962:

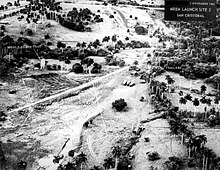

Sunday, October 14th: US President John F. Kennedy (again) approved aerial photographs of the Lockheed U-2 reconnaissance aircraft . U-2 planes flew twice over missile positions in Cuba from Laughlin Air Force Base in Texas. They spotted Soviet technicians and soldiers building launch pads for Soviet medium-range missiles of the SS-4 Sandal and SS-5 Skean type near San Cristóbal and took several photos. The Soviet troops, in turn, discovered the aircraft, but had no orders for countermeasures.

Monday, October 15: The evaluated photos proved the existence of the launch pads for SS-4 medium-range missiles. They were near San Cristóbal in northwest Cuba and would have been able to reach parts of the United States. The longer-range SS-5 missiles were not discovered. Secretary of State Dean Rusk and Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara were informed, security adviser McGeorge Bundy decided not to inform the President until the next morning.

Tuesday October 16: McGeorge Bundy notified John F. Kennedy and immediately convened an Executive Committee (ExComm). Different responses were discussed: accepting the stationing, air strike and invasion. All consultations and results took place without informing the public (and thus also of the Soviet Union). President Kennedy ordered more U-2 reconnaissance flights. At the second ExComm meeting that afternoon, Robert McNamara proposed a naval blockade of Cuba.

Wednesday, October 17: Six more U-2 reconnaissance flights took place over the missile positions. The aerial photographs proved the existence of 16 to 32 missiles (type SS-4 and SS-5 ) with a range of up to 4500 km. In addition to the American capital, these missiles could have reached the most important industrial cities in the USA; the warning time would have been only five minutes. Moreover were IL-28 bomber discovered.

Thursday, October 18: Soviet Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko visited Kennedy, as planned for a long time. Kennedy did not address the situation in Cuba because he wanted to maintain secrecy for tactical reasons. However, the old Soviet demand that West Berlin must be demilitarized was raised several times . This confirmed the American assumption that the Soviet Union wanted to improve its own position in the new Berlin negotiations through its action in Cuba. A view that the Western Allies shared, but which later turned out to be a misinterpretation. Reports of massive new arms shipments to Cuba spread in Washington, DC ; the military grew impatient. The US generals considered a sea blockade to be too weak: one had to act immediately with air strikes and subsequent invasion. Air Force General Curtis E. LeMay urged an attack: "The red dog digs in the backyard of the United States and must be punished for it." Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy , brother of the President, let through his deputy Nicholas deB. Katzenbach examine the legal basis for a sea blockade of Cuba. In the course of the discussions at ExComm, John F. Kennedy preferred a sea blockade.

Friday, October 19: President Kennedy did not want to cause a stir and traveled - according to his schedule - to campaign in Ohio and Illinois. He called on Robert F. Kennedy to get a majority in the ExComm for the blockade option. Katzenbach informed the ExComm about the legal circumstances of the blockade. As a result, the ExComm was divided into two groups, in which various options for combating the missiles in Cuba were worked out. On the one hand stood the hawks (falcons), who preferred the air attack, on the other hand the doves (pigeons), who advocated the more peaceful option of blockade.

Saturday, October 20th: Robert F. Kennedy managed to get a majority in the ExComm for the blockade option. He called the President in Chicago , and he returned to Washington. Although the decision to blockade had been made, the options for an air strike or an invasion of Cuba were kept open.

Sunday October 21: Advisors from the Tactical Air Command (TAC) stated that an air strike could not shut down all Soviet missiles in Cuba. Kennedy then finally approved the sea blockade. In the evening he telephoned the editors of major newspapers ( New York Times , Washington Post , New York Herald Tribune ) to prevent premature reporting.

Monday, October 22nd , one of the most significant days of the crisis: That morning, American newspapers announced a speech by the President of national importance at 7 p.m. Washington time. All US armed forces worldwide were placed in increased operational readiness ( Defense Condition 3), additional US soldiers were relocated to Florida in preparation for an invasion and around 200 warships were positioned around Cuba. The government officials of Great Britain, France, the Federal Republic of Germany and Canada were informed and gave Kennedy their full support. The Swiss embassy, representing the USA, informed the Cubans that night reconnaissance flights would also take place and that the lighting required for this was not a military attack. "No Cuban fire to fear" reported the Swiss embassy back to Washington. Further diplomatic efforts were made in Central and South American states to support the American position in the Organization of American States (OAS) and at the United Nations (UN). In his televised address, Kennedy informed the world public about the Soviet missiles in Cuba and announced the start of the naval blockade for October 24th. He called on the Soviet head of government Nikita Khrushchev to withdraw the rockets from Cuba and threatened a nuclear counter-attack in the event of an attack. From that point on, the Cuban Missile Crisis was public.

Tuesday, October 23: Khrushchev announced that he would not accept the blockade, but assured that the missiles deployed were for defense purposes only. US diplomacy was successful: the OAS voted for action against Cuba and confirmed the sea blockade. This was officially called quarantine, as the term blockade refers to military action.

Wednesday, October 24th: The sea blockade of American warships, which John F. Kennedy called quarantine, began at 10 a.m. Washington time. It came to a head, even though the American ships were not allowed to fire without the President's orders. This was ordered to avoid escalation should the Soviet ships attempt to breach the barrier belt (with a radius of 500 miles). But all Soviet ships turned after the blockade radius was reduced. The Soviet government persisted in its position despite the situation.

Thursday, October 25 , meeting of the UN Security Council in New York City: Between the UN ambassadors Walerian Sorin (USSR) and Adlai Stevenson (USA) was a diplomatic exchange of blows; The US delegation presented the world public for the first time with clear reconnaissance photos of the Soviet missile positions. It later emerged that the number of nuclear missiles had been greatly underestimated by the American side. At a historians' conference in 2002, the then commander in chief of the Soviet armed forces stated that 40,000 Red Army soldiers and 42 missiles had been installed in Cuba, including tactical atomic bombs, the use of which had already been authorized. About 80 nuclear warheads were in Cuba during the crisis. US Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara and Raymond Garthoff, at the time employees of the US State Department, even later stated that the US had not seriously expected that the medium-range missiles in Cuba were actually equipped with nuclear weapons.

Friday, October 26th:

- Despite the blockade, the missiles continued to be stationed in Cuba. The ExComm debated military action. The hardliners advocated air strikes and, if necessary, an invasion. Kennedy received a letter from Khrushchev in which he offered to withdraw the missiles from Cuba if the Americans ruled out an invasion of Cuba. Kennedy promised that. The first freighter that was supposed to be blocked by the American Navy, however, was escorted by several submarines from Project 641 (B-4, B-36, B-59 and B-130). The Americans used training water bombs to force three of the four submarines to surface. As only became known in 2002, in addition to their normal armament, they each had a nuclear torpedo on board and were also authorized to defend themselves with them.

- Despite Defense Condition 2, the highest alert of the armed forces below a war, the US Air Force, led by LeMay, continued the Bluegill Triple Prime test , which led to a whole series , over the Johnston Atoll on October 26 as part of Operation Dominic One of the nuclear bomb tests. However, the ExComm was not informed of this. The USSR also tested two nuclear weapons in the atmosphere in the following days.

- Castro called for a first nuclear strike on US territory in the event of a US invasion . In a letter four days later, Khrushchev replied: “You suggested that we be the first to carry out a nuclear strike on enemy territory. You surely know what that would have done for us. This would not be an easy blow, but the start of the nuclear war. Dear Comrade Castro, I consider your proposal to be incorrect. "

Saturday, October 27 , the Black Saturday :

- In the morning in Cape Canaveral , USA, a test was carried out with the new intercontinental ballistic missile LGM-25C Titan II (USAF serial no. 61-2735), about which ExComm was also not informed.

- The Völkerfreundschaft , a GDR vacation ship with 500 passengers on board, ignored the Americans' ring of blockade and risked being upset by them. John F. Kennedy prevented this personally, so the ship could enter Havana .

- A US destroyer used training water bombs to force the Soviet submarine B-59 to surface, it had a nuclear torpedo on board. Once again, the whole world was on the brink of nuclear war. But Vasily Alexandrowitsch Archipow , one of the three officers on board the submarine who were responsible for launching nuclear weapons, refused to fire the torpedo without further orders from Moscow.

- An American reconnaissance plane got lost in Soviet airspace and fighter planes took off. The US plane narrowly escaped.

- Another letter from Khrushchev arrived in the United States. In it, the missile withdrawal was tied to a promise of non-attack by the USA as well as to the withdrawal of the American Jupiter missiles from Turkey.

- An American U-2 spy plane was shot down by an S-75 anti-aircraft missile over Cuba ; the pilot, Major Rudolf Anderson , was killed. Kennedy expressly forbade a counterattack and again agreed to further negotiations.

- At 7:45 p.m. Washington time, a secret meeting took place between Robert F. Kennedy and the Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin . John F. Kennedy let his brother explain that he would also consent to the withdrawal of the American Jupiter rockets stationed in Turkey , as requested in the second - more formal - letter from Khrushchev. He kept this possibility a secret from most of the members of the ExComm, the majority of whom called for an air strike. Dobrynin immediately relayed this news to Moscow. Late that night, Nikita Khrushchev decided to accept Kennedy's offer and withdraw the missiles from Cuba.

Sunday, October 28 , the secret diplomacy is successful.

- Khrushchev relented and agreed to remove the missiles. In return, the United States agreed not to invade Cuba. In addition - which was not allowed to be made public - the rockets were dismantled in Turkey.

- The withdrawal of the Soviet missiles was announced by Khrushchev on Radio Moscow . The crisis was over.

- The MS Völkerfreundschaft received the request from East Berlin to leave Havana immediately and set course for the home port.

Binding solution to the conflict

The two states agreed the following conditions: The Soviet Union withdraws its missiles from Cuba. On the other hand, the United States declares that it will not undertake any further military invasion of Cuba and will for its part withdraw the American Jupiter rockets from Turkey in a secret agreement . The withdrawal from Turkey will take place a little later and in camera, so as not to snub the US's NATO partners and to be able to portray the United States as the winner of the crisis.

On November 5, the medium-range missile withdrawal from Cuba began, which was officially completed within five days. The Soviet Union's original plan was to transfer the missiles to the Cubans. But when Khrushchev learned on November 15, 1962 that Castro did not shy away from using them to attack the USA either, he decided to send all nuclear warheads back to the Soviet Union and to leave only a few conventionally armed short-range missiles on the island. On November 20, 1962 - after the Soviet medium-range missiles had officially withdrawn - the USA finally dissolved the naval blockade around Cuba. The actual withdrawal of the missiles was not completed until early January 1963.

Apart from this publicity, the events of 1962 were, from the point of view of the two superpowers, the USA and the Soviet Union, a tactical victory for the other side; this emerges from secret speeches published later by the respective presidents Kennedy and Khrushchev and increased the mistrust of the military leaderships of both countries against their own governments.

After the crisis, Soviet FROG short-range missiles remained on the island. Although they could not hit US cities due to the short range, they could threaten the US base in Guantanamo Bay and approaching ships. The danger posed by the remaining missiles in Cuba was known to the United States in the aftermath of the crisis and was accepted because the FROG missiles could be viewed as defensive weapons.

Analysis of the political action of the conflicting parties

Political science's investigation of the Cuban Missile Crisis focuses primarily on the actors' scope for action and decisions. Central to solving the Cuban Missile Crisis was that both John F. Kennedy and Nikita Khrushchev were aware of the consequences of their decisions. Both tried to keep all developments under control, to give the political opponent time to make his decision and not to blindly trust the advice of their military advisers.

Immediately after the Cuban Missile Crisis, Kennedy declared that the danger was not seen in the fact that the Soviet Union could fire missiles from Cuba at the USA, but that the balance of power in favor of the Soviet Union would appear to have been unbalanced.

Consequences of the crisis

The immediate results of the Cuban Missile Crisis were a tactical success for the Soviet Union, as the withdrawal of US nuclear missiles from Turkey and Italy resulted in a more favorable situation for the Soviet Union than the previous status quo .

However, the crisis also led to the first negotiations on arms control . For example, on August 5, 1963, a treaty banning nuclear weapons tests in the atmosphere, in space and under water was signed in Moscow and, from 1969, the SALT agreements were also negotiated, which limited the ICBMs of both countries. From then on there was a détente between the two superpowers. So they tried to avoid direct confrontation and instead waged proxy wars in Vietnam and Afghanistan. After the crisis, their interests were also concentrated on those areas of the globe that were not yet clearly divided between East and West.

Kennedy deprived the military of their independent disposal of nuclear weapons by introducing a nuclear activation code in the hands of the US President, which is absolutely necessary for a nuclear strike and which can be transmitted via the so-called nuclear suitcase . Since then, the presidents have always carried the code with them. The USSR also introduced such a system in 1968. For Kennedy personally, averting the crisis went hand in hand with an increase in his popularity among the American population. Since the withdrawal of the Jupiter rockets from Turkey was not made public, Kennedy was able to profile himself in public as a hardliner who had forced the USSR to give in with a show of power.

In order to avoid misunderstandings and direct confrontations that could endanger peace, the exchange of information between the great powers has been improved. For example, in 1963, as a further response to the crisis, the hot wire was established, a direct telex connection between the White House and the Kremlin that was intended to enable direct contact between statesmen. In this way, immediate negotiations should be possible in a crisis situation so that an escalation can be averted. The hot wire was first used on June 5, 1967, shortly after the beginning of the Six Day War that broke out between Israel and the Arab states of Egypt , Jordan and Syria . Even after that, it was used in a number of other conflicts during the Cold War.

Furthermore, the USA tightened its embargo against Cuba again after the crisis. Cuba responded with an even closer connection to the Soviet Union.

The Cuban Missile Crisis ultimately led to a new relationship between the superpowers, which was expressed in a mutual détente policy . The foreign policy doctrines were also renewed. The USA switched to a military strategy of flexible response (sometimes even before the crisis) and in the Soviet Union Khrushchev now proclaimed peaceful coexistence .

Movies

- Peter von Zahn : The Cuba Crisis 1962. ZDF , documentary and television play, 1969. Director: Rudolf Nussgruber .

- The Missiles of October . USA 1974, directed by Anthony Page.

- The Cuban Crisis. FRG 1984, theater play by the Berlin company

- Thirteen Days . USA 2000, directed by Roger Donaldson.

- The Cuban Missile Crisis . USA 2000, interviews and background information.

- Werner Biermann: On the Abyss - Anatomy of the Cuban Crisis. WDR, 2002, documentation.

- The Fog of War : Eleven Lessons from the Life of Robert S. McNamara . Documentation.

- Tapes of debates between JFK and his advisors during the crisis

- Mad Men : Meditations in an Emergency. Season 2, episode 13, USA 2008.

- The Kennedys : On the Brink of War. Episode 6, USA 2011.

- Günther Klein (direction + book), Stefan Brauburger (book): The test of nerves. - Cuba crisis 1962. IFAGE Filmproduktion, ZDF et al. 2002

- Stefan Brauburger, Bärbel Schmidt-Šakić: On the verge of nuclear war - fight for Cuba and Berlin. (ZDF 2012)

- The Coldest Game , Poland 2019

See also

literature

- Graham T. Allison, Philip Zelikow: Essence of Decision - Explaining the Cuban Missile Crisis. 2nd edition, Longman, New York et al. a. 1999 (first edition: Boston 1971), ISBN 978-0-321-01349-1 (English).

- John C. Abroad: Kennedy, Khrushchev, and the Berlin-Cuba crisis, 1961–1964. Oslo 1996, ISBN 82-00-22635-2 (English).

- Stefan Brauburger : The test of nerves, location Cuba: When the world stood on the brink. Foreword by Guido Knopp . Campus, Frankfurt am Main 2002, ISBN 3-593-37096-4 .

- Mathias Uhl, Dimitrij N. Filippovych (ed.): Before the abyss. The armed forces of the USA and USSR and their German allies in the Cuba crisis . Munich, Oldenbourg 2005, ISBN 3-486-57604-6 (= series of the quarterly books for contemporary history , special issue).

- Aleksandr A. Fursenko, Timothy J. Naftali: One Hell of a Gamble. Krushchev, Castro & Kennedy 1958–1962. The Secret History of the Cuban Missile Crisis. Norton, New York 1997, ISBN 0-393-04070-4 (English).

- Bernd Greiner : Cuban Crisis. 13 days in October. Analysis, documents, contemporary witnesses. Greno , Nördlingen 1988, ISBN 3-89190-956-X (= writings of the Hamburg Foundation for Social History of the 20th Century ; Volume 7: Evaluation of the tape minutes of the secret US presidential deliberations).

- Bernd Greiner : The Cuban Crisis. The world on the threshold of nuclear war. Beck, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-58786-3 (= Beck'sche series , volume 2486 CH Beck Wissen ).

- Roger Hilsman: The Cuban Missile Crisis. The struggle over policy , Westport 1996, ISBN 0-275-95435-8 (English).

- Robert F. Kennedy ; Theodore C. Sorensen (Ed.): Thirteen days. The prevention of the Third World War by the Kennedy brothers (original title: Thirteen Days, a Memoir of The Cuban Missile Crisis. Translated by Irene Muehlon). Scherz, Bern 1969; 2nd edition: Thirteen days when the world almost ended. Darmstädter Blätter, Darmstadt 1982, ISBN 3-87139-076-3 ; as a paperback: Thirteen Days or The Prevention of World War III. rororo 6737; Reinbek near Hamburg 1970, ISBN 3-499-16737-9 .

- Christof Münger: Kennedy, the Berlin Wall and the Cuban Missile Crisis. The Western Alliance in the acid test 1961–1963. Schöningh , Paderborn / Munich / Vienna / Zurich 2003, ISBN 3-506-77531-6 (also dissertation at the University of Zurich 2002).

- James A. Nathan: Anatomy of the Cuban Missile Crisis . Westport 2001, ISBN 0-313-29973-0 (English).

- Arnold Piok: Kennedy's Cuba Crisis - Planning, Error and Luck on the Edge of the Nuclear War 1960–1962. Tectum , Marburg 2003, ISBN 978-3-8288-8587-5 (= Diplomica , Volume 11, also a master's thesis at the University of Innsbruck 2000 under the title: Thirteen Days ).

- Horst Schäfer : In the crosshairs: CUBA. Kai Homilius Verlag (Contemporary History Edition), Berlin 2004, ISBN 9783897068766 .

- Rolf Steininger: The Cuban Missile Crisis 1962. Thirteen days on the atomic abyss , Olzog , Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-7892-8275-1 .

- Heiner Timmermann (Ed.): The Cuban Crisis 1962. Between Mice and Mosquitoes, Disasters and Tricks, Mongoose and Anadyr , Lit , Münster 2003, ISBN 978-3-8258-6676-1 (= documents and writings of the European Academy Otzenhausen. Volume 109).

- Mark J. White: Missiles in Cuba - Kennedy, Khrushchev, Castro and the 1962 Crisis. van R. Dee, Chicago 1998, ISBN 978-1-56663-156-3 (English).

Web links

- Literature on the Cuban Missile Crisis in the catalog of the German National Library

- Harald Biermann : NATO in the Cuban Crisis - IMS No. 2, 2009; 60 years of NATO

- Andreas Grau, Markus Würz: Cuba Crisis , in: LeMO ( DHM and HdG )

- Ingo Juchler: Revolutionary hubris and the danger of war: The Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962 (PDF; 7.4 MB) in: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte, Volume 41 (1993) Issue 1, pp. 79-100, accessed on June 1, 2012.

- Joachim Kohnen: Operation "Armageddon" - the world on the verge of nuclear war - very detailed article on geschi.de ( Memento from June 28, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- Horst Schäfer : How a war was prevented. Neue Rheinische Zeitung online flyer No. 379 of November 7, 2012 (last accessed on March 15, 2020).

- The test of nerves - Cuba 1962. December 22, 2007, accessed November 16, 2010 .

- National Security Archive - Released Intelligence; Photos ( National Security Archive , George Washington University , Washington, DC )

Individual evidence

- ↑ Wolfgang Bayer: Secret Operation Fürstenberg . In: Der Spiegel . No. 3 , 2000 ( online ).

- ↑ Jon Lee Anderson: Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life. New York: Grove Press 1998, ISBN 0-8021-3558-7 , here p. 417.

- ↑ Dimitrij N. Filippovych, Vladimir I. Ivkin: The strategic missile forces of the USSR and their participation in the operation "Anadyr". In: Dimitrij N. Filippovych, Mathias Uhl (Ed.): Before the Abyss. R. Oldenbourg, 2005.

- ↑ Bodo Hechelheimer: The Federal Intelligence Service and the Cuba Crisis ( Memento of March 24, 2014 in the Internet Archive ), 2012-10-12 (PDF; 647 kB), in: Communications of the research and working group “History of the BND” No. 3, Vol. 1, p. 11, accessed December 9, 2012.

- ↑ A pot of spaghetti with the Máximo Líder , Tagi, July 4th 2015

- ^ David G. Coleman: The Missiles of November, December, January, February… The Problem of Acceptable Risk in the Cuban Missile Crisis Settlement. In: Journal of Cold War Studies. 9, 3, 2007, pp. 5-48, here p. 10 f.

- ^ A b The Submarines of October. In: nsarchive2.gwu.edu. Retrieved May 10, 2020 (Russian).

- ^ Bert Hoffmann: Kuba , p. 76 limited preview in the Google book search

- ↑ Titan II in the Encyclopedia Astronautica (English)

- ↑ GDR dream ship in danger. The adventurous Havana trip of 'Friendship of Nations' during the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962 is filmed. MAZ January 17th, 2014.

- ^ Leslie H. Gelb: The Myth That Screwed Up 50 Years of US Foreign Policy . 2012. Retrieved September 25, 2013.

- ^ David G. Coleman: The Missiles of November, December, January, February… The Problem of Acceptable Risk in the Cuban Missile Crisis Settlement. In: Journal of Cold War Studies, 9, 3, 2007, pp. 5–48, here p. 23.

- ^ David G. Coleman: The Missiles of November, December, January, February… The Problem of Acceptable Risk in the Cuban Missile Crisis Settlement. In: Journal of Cold War Studies, 9, 3, 2007, pp. 5–48, here p. 29 f.

- ^ David G. Coleman: The Missiles of November, December, January, February… The Problem of Acceptable Risk in the Cuban Missile Crisis Settlement. In: Journal of Cold War Studies, 9, 3, 2007, pp. 5–48, here p. 12.

- ^ John Lewis Gaddis : Strategies of Containment. A critical appraisal of American national security policy during the Cold War. edited and supplemented edition, Oxford 2005, p. 211 f.

- ↑ National Security Action Memorandum No. 272

- ↑ http://www.phoenix.de/184715.htm ( Memento from March 13, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) , video on YouTube