Cultural appropriation

This item has been on the quality assurance side of the portal sociology entered. This is done in order to bring the quality of the articles on the subject of sociology to an acceptable level. Help eliminate the shortcomings in this article and participate in the discussion . ( Enter article )

Reason: At the moment, only the reception of the term by the critical whiteness movement is presented. There is therefore already a neutrality module. The problem with the article is deeper, especially since it was derived from a translation of the enWP article without importing the history. - Trinitrix ( discussion ) 14:34, Sep 18. 2017 (CEST)

Cultural appropriation is the term used for different social, cultural and media science terms. “Cultural appropriation” was first mentioned in the 1970s and 1980s. As in current ethnological parlance, cultural appropriation refers there v. a. on the “difference between different ways of perceiving cultural phenomena”. Cultural appropriation can be understood as a “process of structured transformation” in that after a contact (also: acceptance, acquisition) objects with specific properties are subjected to various transformations. The sub-processes of the transformation include the redesign, the (re) naming, the (possibly different) contextualization and the incorporation of the object. The interaction of one or more sub-processes gives rise to new traditions.

With a different accent cultural appropriation is (English cultural appropriation ) in the US Critical Whiteness used movement. The term is used here u. a. to reflect on power and discrimination relationships, on the basis of which traditional objects of the material culture of different ethnic groups are instrumentalized as a substrate for commercialization processes. This form of cultural appropriation is criticized because the cultures concerned can be lost or falsified. In addition, external commercialization can impair economic activity in the ethnic groups concerned.

Terminology

According to the French cultural philosopher Michel de Certeau, cultural appropriation is a “space for the powerless to act”. According to Certeau, actors find opportunities in everyday life to deviate from given patterns of action and to change their meaning in a possibly “subversive” way. The objects appropriated in this way could also be everyday objects, social institutions, knowledge systems or norms.

The discourse of the critical whiteness movement, on the other hand, focuses on specifically “cultural” objects. Examples include different genres of art (music, dance, etc.) or religious things (symbols, spirituality , ceremonies ), but also fashion and language styles , social behavior and other forms of cultural expression.

The propriety of cultural appropriation is the subject of lively debate. Opponents see it as a theft. It is particularly critical when the culture belongs to a minority that is socially, politically, economically or militarily disadvantaged, for example because of ethnic conflicts . The suppressed culture would then be torn out of its context by its historical oppressors.

Criticism of the concept

Proponents see some appropriation as inevitable or as an enrichment that occurs out of admiration and without malice. It is a contribution to diversity. Even in early history there were lively cultural transfers on the Silk Road . Without cultural appropriation, Central Europeans would not be able to sit on sofas or eat apple strudel , both of which have their origins in Asian cultures. The concept of cultural appropriation is more of an absurdity.

The literary scholar Anja Hertz sees in the uncompromising criticism of cultural appropriation the danger of seeing culture too much as something uniform and clearly limited; according to Hertz, the accusation of cultural appropriation implies “a reactionary idea of cultural purity”. Marcus Latton wrote in Jungle World that the "real existing anti-racism " runs the risk of turning into its opposite, since among other things, any criticism of a culture is undifferentiated without legitimation. Such a re-essentialization of culture is analytically as well as politically problematic, writes sociologist Jens Kastner.

According to the social scientist Samuel Salzborn , the concept of cultural appropriation is based on the idea that there are “something like 'authentic' and thus collectively fixed elements of a sub- or minority culture [...] that should only be reserved for this culture”. This idea is "however entirely ahistorical". It amounts to a homogenization of social relationships and an ethnicization , that is, the incapacitation of the subject, because being able to decide for or against belonging to a group and its cultural identity is “the core of freedom, the generally must be directed against any culturalization ”.

On the occasion of a discussion on cultural appropriation at the Anne Frank educational institution , the gender researcher Patsy l 'Amour laLove criticized the concept as folkloric : foreign cultures are presented as particularly "pure" and "original" and thus ultimately led to an exoticization . In addition, parallel to character traits, it is not possible to link cultural practices with certain ethnic groups.

Motifs

The cultural theorist George Lipsitz sees the calculated use of other forms of culture as a strategy with which a group defines itself. This occurs with both the majority and the minority, so it is not limited to one side. The majority culture should, however, take into account the socio-historical circumstances of the appropriated culture in order not to perpetuate the historically unequal power relations. According to this view, the resistance of cultural minorities against the majority society (e.g. in imitating and changing aspects of the majority culture) is excluded from the concept of cultural appropriation, because here the balance of power is reversed. A historical example is the emergence of mods in the UK in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Working-class youth in particular imitated and exaggerated the tailored clothing style of the upper middle class, using iconic British symbols such as the Union Jack and the Royal Air Force cockade . This recontextualization of cultural elements can also be viewed as cultural appropriation, but it usually has no negative connotations.

Examples

antiquity

The historically most controversial cases took place in places where cultural exchange was highest, such as along the trade routes in Southwest Asia or Southeast Europe .

- Some scholars argue that the architecture of the Ottoman Empire and Ancient Egypt was mistakenly given as Persian or Arabic for a long time.

present

- Jewelry or fashion with religious symbols without the wearer believing these religions. Examples are the warbonnet , medicine wheel , cross , mehndi or the wearing of a bindi by non- Hind women in South Asia .

- Imitation of the iconography of other cultures without considering their cultural significance ( kitsch ), such as characters from Polynesian tribes, Chinese characters , Celtic art .

- Wearing costumes on Mardi Gras or Halloween that are based on stereotypes and whose wearers do not belong to the corresponding ethnic group. Costumes such as "Vato Loco" (means crazy Chicano from Watts , colloquially "Vato"), "Pocahottie" (from Pocahontas ), "Indian Warrior" or "Kung Fool" (from Kung Fu ).

In the present, various pop singers and actors have been accused of illegitimate cultural appropriation:

- Selena Gomez wore a bindi during a performance .

- Pharrell Williams posed in a war bonnet on the front page of ELLE UK in 2014 .

- Avril Lavigne used Japanese culture in the music video for her song Hello Kitty : The video shows Asian women dressed in appropriate costumes and Lavigne dressed in a pink tutu .

- Karlie Kloss wore an Native American feather bonnet and moccasins at the 2012 Victoria's Secret fashion show .

- Bo Derek wore cornrows .

- In 2017, the African-American conceptual artist Hannah Black demanded the destruction of the painting Open Casket by the European-born painter Dana Schutz. The painting is based on a photo of Emmett Till's corpse , a victim of racist violence in 1955.

Minorities

Indians

Sports teams at US universities often use symbols of Indian tribes as mascots, which, according to critics, contradicts their educational mandate. As a result, the NCAA issued a guideline in 2005 that changed names and mascots, with the exception of indigenous educational institutions. According to the NCAI , two thirds of all names and mascots have been phased out in the past 50 years. Some Indian tribes, however, approve of mascots, such as that of the Seminoles, the use of their chief Osceola and his Appaloosa "Renegade" by the FSU football team . The General Assembly of the United Nations issued a statement against the appropriation of indigenous culture. In 2015, a group of indigenous scientists and authors published a statement against rainbow gatherings .

African American

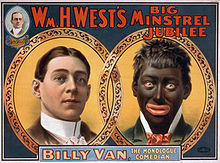

Blackface is a masquerade of white performers to portray black people . It became popular in the 19th century and contributed to the spread of negative stereotypes, such as ethnophaulisms . In 1848, minstrel shows were popular with the general public. In the early 20th century, blackface was diverted from minstrel shows and became a genre of its own until the US civil rights movement of the 1960s.

The term wigger is slang for white people who imitate African American subculture, such as African American English and street fashion in the US and grime in the UK. The phenomenon appeared a few generations after the end of slavery in predominantly "white countries" such as the USA, Canada, Great Britain and Australia. An early form was the white negro in jazz and swing of the 1920s and 1930s. Norman Mailer explored this in his 1957 essay The White Negro . Zoot Suiters followed in the 1930s and 1940s, hipsters in the 1940s , beatnik in the 1950s and 1960s, blue-eyed soul in the 1970s and hip-hop in the 1980s and 1990s . Today, African American culture is spread and marketed worldwide.

Aboriginal

In Australia, indigenous artists have discussed an “authentic brand” to educate consumers about inauthentic art.

This movement took off after 1999 when John O'Loughlin was convicted of fraud for selling art that was purportedly painted by indigenous artists.

Web links

- Katie JM Baker: A Much-Needed Primer on Cultural Appropriation

- Chinese Tattoos, Year of the Dragon, and Commodifying Buddhism in Model Minority

- James O. Young: Cultural Appropriation and the Arts ; Review in the Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews

- Declaration Of War Against Exploiters Of Lakota Spirituality

- Intellectual Property in the Dreamtime

- Megan M. Carpenter: Intellectual Property Law and Indigenous Peoples: Adapting Copyright Law to the Needs of a Global Community ; The Yale Human Rights and Development Journal

- No More War Bonnets at Glastonbury Music Festival from the Lakota Law Project

- Meagan Wohlberg: Northern-sparked 'ReMatriate' campaign takes on cultural appropriation

- Susan Scafidi: Who Owns Culture? Authenticity and Appropriation in American Law ( Memento from November 8, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

- Marcus Latton: Customs for each tribe

- Lionel Shriver: 'I hope the concept of cultural appropriation is a passing fad'

Individual evidence

- ↑ Hans Peter Hahn (2011) Antinomies of Cultural Appropriation: An Introduction. Zeitschrift für Ethnologie 136 (2011) 11–26; Quote p. 11

- ↑ Hans Peter Hahn (2011) Antinomies of Cultural Appropriation: An Introduction. Journal of Ethnology 136 (2011) 11–26

- ↑ Linda Martin Alcoff: What Should White People Do? . In: Hypatia . 13, No. 3, 1998, pp. 6-26. doi : 10.1111 / j.1527-2001.1998.tb01367.x . Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ^ A b Adrienne Keene: But Why Can't I Wear a Hipster Headdress? at Native Appropriations - Examining Representations of Indigenous Peoples . April 27, 2010

- ↑ Kjerstin Johnson: Don't Mess Up When You Dress Up: Cultural Appropriation and Costumes . ( Memento of the original from June 29, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. at Bitch Magazine , October 25, 2011. Accessed March 4, 2015. 'Dressing up as "another culture," is racist, and an act of privilege. Not only does it lead to offensive, inaccurate, and stereotypical portrayals of other people's culture ... but is also an act of appropriation in which someone who does not experience that oppression is able to "play," temporarily, an "exotic" other, without experience any of the daily discriminations faced by other cultures. '

- ↑ a b Eden Caceda: Our cultures are not your costumes . Retrieved January 20, 2015.

- ^ A b Sundaresh, Jaya (May 10, 2013) " Beyond Bindis: Why Cultural Appropriation Matters " for The Aerogram.

- ↑ Uwujaren, Jarune (Sep. 30, 2013) “ The Difference Between Cultural Exchange and Cultural Appropriation ” for everdayfeminism.com .

- ^ Cathy Young: To the New Culture Cops, Everything is Appropriation . In: The Washington Post . August 21, 2015. Retrieved December 6, 2015.

- ^ John McWhorter, You Can't 'Steal' A Culture: In Defense of Cultural Appropriation . Retrieved October 20, 2014.

- ↑ Jeff Jacoby: Three cheers for cultural appropriation . In: The Boston Globe . December 1, 2015. Accessed December 6, 2015.

- ↑ Josef Joffe: Cultural Appropriation: Who Owns It? . In: Die Zeit, January 6, 2017, accessed on May 17, 2017.

- ↑ He who is most oppressed is right. In: Analysis & Criticism . February 16, 2016, accessed October 4, 2016 .

- ↑ To each tribe its customs. In: jungle-world.com. Retrieved September 15, 2016 .

- ↑ Comandante Brus Li eats sushi. Retrieved November 5, 2016 .

- ^ Samuel Salzborn: Global anti-Semitism. A search for traces in the abyss of modernity. Beltz Juventa, Weinheim 2018, p. 101 f.

- ↑ Bildungsstätte Anne Frank - Streitbar # 9: Cultural Appropriation - February 2020 - 2:01:32. Retrieved April 21, 2020 (English).

- ↑ Darren Lee Pullen (Ed.): Technoliteracy, Discourse, and Social Practice: Frameworks and Applications in the Digital Age . IGI Global, 2009, ISBN 1-60566-843-5 , p. 312.

- ^ Robert Ousterhout: Ethnic Identity and Cultural Appropriation in Early Ottoman Architecture . ( Memento of the original from June 13, 2006 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Muqarnas Volume XII: An Annual on Islamic Art and Architecture. EJ Brill, Leiden 1995. Retrieved January 3, 2010.

- ^ Salil Tripathi: Hindus and Kubrick . In: The New Statesman . September 20, 1999. Retrieved November 23, 2006.

- ↑ a b c Adrienne Keene: Open Letter to the PocaHotties and Indian Warriors this Halloween . at Native Appropriations - Examining Representations of Indigenous Peoples , October 26, 2011. Accessed 4 March 2015

- ↑ Jennifer C. Mueller, Danielle Dirks, Leslie Houts Picca: Unmasking Racism: Halloween Costuming and Engagement of the Racial Other . In: Qualitative Sociology . tape 30 , no. 3 , April 11, 2007, ISSN 0162-0436 , p. 315-335 , doi : 10.1007 / s11133-007-9061-1 .

- ↑ Escobar, Samantha (17 October 2014) " 13 Racist College Parties That Prove Dear White People Isn't Exaggerating At All ( Memento of the original from May 18, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. “At The Gloss . Accessed March 4, 2015

- ↑ Cultural Appropriation - Is It Ever Okay? . Retrieved November 9, 2015.

- ↑ Pharrell apologizes for Wearing Headdress on Magazine Cover . Retrieved November 9, 2015.

- ^ Stephanie Caffrey: Culture, Society and Popular Music; Cultural Appropriation in Music . Archived from the original on December 22, 2015. Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Retrieved December 12, 2015.

- ↑ Karlie Kloss, Victoria's Secret Really Sorry About That Headdress . Retrieved December 6, 2015.

- ^ Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung GmbH: Cultural appropriation: They are not allowed to. September 13, 2017. Retrieved September 14, 2017 .

- ↑ Hanno Rauterberg : Dance of the guardians of virtue . In: Die Zeit from July 27, 2017, p. 37.

- ^ Robert Longwell-Grice, Hope Longwell-Grice: Chiefs, Braves, and Tomahawks: The Use of American Indians as University Mascots . In: NASPA Journal (National Association of Student Personnel Administrators, Inc.) . 40, No. 3, 2003, ISSN 0027-6014 , pp. 1-12. doi : 10.2202 / 0027-6014.1255 . Retrieved October 29, 2014.

- ^ Angela Riley: Straight Stealing: Towards an Indigenous System of Cultural Property Protection . In: Washington Law Review . 80, No. 69, 2005.

- ^ Statement of the US Commission on Civil Rights on the Use of Native American Images and Nicknames as Sports Symbols . The United States Commission on Civil Rights. April 13, 2001. Retrieved June 13, 2012.

- ^ Anti-Defamation and Mascots . National Congress of American Indians. Retrieved January 12, 2013.

- ↑ Jacki Lyden: Osceola At The 50-Yard Line . In: NPR.org . November 28, 2015. Accessed December 6, 2015.

- ↑ Chuck Culpepper: Florida State's Unusual Bond with Seminole Tribe Puts Mascot Debate in a Different Light . In: The Washington Post . December 29, 2014. Retrieved December 6, 2015.

- ↑ Mesteth, Wilmer et al .: Declaration of War Against exploiters of Lakota Spirituality . June 10, 1993.

- ↑ Valerie Taliman: Article On The 'Lakota Declaration of War'. 1993.

- ↑ Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples ( Memento of the original from June 26, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF) Working Group on Indigenous Populations, accepted by the United Nations General Assembly , UN Headquarters, New York City, September 13, 2007.

- ↑ Estes, Nick; et al. " Protect He Sapa, Stop Cultural Exploitation ( Memento of the original from March 3, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. “At Indian Country Today Media Network . 14 July 2015. Accessed 24 Nov 2015

- ^ William J. Mahar: Behind the Burnt Cork Mask: Early Blackface Minstrelsy and Antebellum American Popular Culture . University of Illinois Press, 1998, ISBN 0-252-06696-0 , p. 9.

- ^ Frank W. Sweet: A History of the Minstrel Show . Backintyme (2000), ISBN 0-939479-21-4 , p. 25

- ↑ Bernstein, Nell: Signs of Life in the USA: Readings on Popular Culture for Writers , 5th ed. 607

- ^ Jason Rodriquez: Color-Blind Ideology and the Cultural Appropriation of Hip-Hop . In: Journal of Contemporary Ethnography , 35, No. 6 (2006), pp. 645-68.

- ↑ Eric Lott: Darktown Strutters. - book reviews . In: African American Review , Spring 1997.

- ^ Marianne James: Art Crime. ( Memento of the original from January 11, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF) In: Trends and Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice , No. 170. Australian Institute of Criminology. October 2000; The Aboriginal Arts 'fake' controversy. In: European Network for Indigenous Australian Rights. July 29, 2000.

- ^ Aboriginal art under fraud threat. . BBC News dated November 28, 2003.