List of mines in the Palatinate

Ore mining in the Palatinate mainly dealt with iron, copper and mercury. Iron and copper were mainly of local importance, mercury was traded supraregional. The coal reserves were small and only used locally. Mining on clay was also of supraregional importance .

Mining centers were at Donnersberg , especially Imsbach , at Stahlberg , at Lemberg , at Obermoschel , at Potzberg and at Kaiserslautern , as well as for clay deposits at Eisenberg . The earliest traces of mining come from Roman times (1st century AD), ore mining ended in the 1940s, and clay mining is still in progress. See also: Mining in the Palatinate .

Thunder Mountain

Mining in the Donnersberg region was mainly based on copper, cobalt and iron ores.

| Surname | Local parish | comment | location |

|---|---|---|---|

| B-studs | Imsbach | Experimental tunnel, excavated around 1916–1920; as well as a tunnel approach from the 15th or 16th century in the immediate vicinity | location |

| Katharina I pit | Imsbach | Copper, later also silver; Opencast mining in the 9th century by the Prüm Abbey , around 1120 by the Marienthal Monastery , later tunnel construction; Drainage through Blanches tunnels into the copper pond | location |

| Catherine II pit | Imsbach | Copper, later also silver; see Grube Katharina I | location |

| Bienststand studs | Imsbach | Copper; short tunnel with cross passages and a small widening , started in the 15th or 16th century, abandoned in the 18th century, attempted again from around 1900 | location |

| Devil studs | Imsbach | Experimental tunnel around 1905; renewed search around 1920; no degradation | location |

| Friedrich-August-Erbstollen | Imsbach | Built from 1882 to 1891, length 210 m, connection to Theodor-Schacht, the Erni pit, the Ida pit and the Friedrich-Stollen pit. Drainage and conveyor tunnels, used in the last operating phase to guide the power lines and compressor pipes to the Theodor shaft | location |

| Theodor Schacht | Imsbach | Copper; Depth 85 m; sunk 1918 to 1921, no successful mining | location |

| Grube Erni and Grube Ida | Imsbach | Copper and cobalt (Erni mine), manganese (Ida mine); both pits form a unit; Opened in 1880; connected to Friedrich-August-Erbstollen. | location |

| Friedrich-Stollen mine | Imsbach | Copper; Started in 1880; connected to Friedrich-August-Erbstollen; Mouth hole in Schweinstal | location |

| A-studs | Imsbach | Search tunnel; around 1918; Called A-studs | location |

| Schartenrück tunnel | Imsbach | Copper; Search tunnel, from 1910; only slight copper mineralization was found, mining was not worthwhile | location |

| Lebach tunnel | Imsbach | Copper; Search tunnel from 1892, closed the following year, no dismantling | location |

| Pit Green Lion | Imsbach | Copper; before 1726 | location |

| stollen | Imsbach | Tunnels with an unknown purpose, not shown on mine maps | location |

| Experimental shaft | Imsbach | Manganese; Search shaft with a few cross passages, from 1885; the continuation of the manganese ore train from the Ida mine could not be found. | location |

| Pit gray pike | Imsbach | Hard coal; Schacht was sunk in 1882 in search of copper, but no profitable ores were found; instead, a small coal deposit was exploited. Schachtpingen in the vicinity and the opening of old mines during hard coal mining are evidence of earlier mine buildings. | location |

| Eugene Stollen | Imsbach | Starting in 1908 as an access tunnel for the Hecht pit (ore transport and ventilation), after 360 m of tunneling, a small coal seam was driven, this was dismantled from 1920 by the Ernst trade union , which was founded for this purpose, but the poor quality of the coal led to a year later End of operation. | location |

| Pit rich debris | Imsbach | copper | location |

| White pit | Imsbach | Copper and silver; Beginning before the 14th century (evidenced by ceramic finds), in the 17th century lying idle (Thirty Years War and its consequences), in the 18th century named Count Friedrich in yield and mine, renamed from 1769 to St Josephi mine. Provisional cessation of operations in 1787. Re-commissioning from 1841, renaming to White Mine in 1882. Final end of 1920 due to ore shortage. Today visitors mine. | location |

| Mary's Pit | Imsbach | Iron; today visitor mine | location |

| Aya shafts | Imsbach | Shaft pits without tunnels, up to 9 m depth, 15th or 16th century | location |

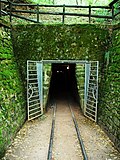

| Deep Gienanth tunnel | Imsbach | Driven 1840–1865; Drainage of the Frieda mine field (iron ore dike), length approx. 1700 m, now secured with an access hatch, not collapsed | Location (approx.) |

| Gienanth Erbstollen (Iron Gate) | Imsbach | From 1773; Drainage of the Frieda mine field (iron ore vein), length approx. 500 m | Location (approx.) |

| Blanches studs | Imsbach | Drains pits Katharina I and II into the copper pond, in operation from 1901, length 310 m | Location (approx.) |

| Red heap | Imsbach | Iron; narrow strip along the Langental, length of the pit field 2800 m, started before 1534, probably Roman | location |

| 5 bays | Imsbach | Copper; leveled by agriculture nowadays; probably from Roman times | location |

| Iron ore mine | Imsbach | Iron; started in the 1st or 2nd century (Roman), next evidence from the 14th century, from 1476 to 1660 iron mining is continuously documented, temporary closure until 1742, then taken over by Johann Nikolaus Gienanth, who expanded the mines on a large scale and also had deep water solution tunnels driven (Gienanth-Erbstollen and Tiefer Gienanth-Erbstollen), end of operation in 1868. Between 1901 and 1921 isolated mining of colored ores. Last investigation in 1938 and 1940, without start of operation. | location |

| Iron ore mine | Imsbach | Iron; historical background s. O. | location |

| Iron ore mine | Imsbach | Iron; historical background s. O. | location |

| Iron ore mine | Imsbach | Iron; historical background s. O. | location |

| Iron ore mine | Imsbach | Iron; historical background s. O. | location |

| Iron ore mine | Imsbach | Iron; historical background s. O. | location |

| Iron ore mine | Imsbach | Iron; historical background s. O. | location |

| Water tunnel | Imsbach | No mining known, age unknown, used to supply water to the mine (Langentaler Hof) | location |

| Experimental tunnel | Imsbach | location |

Kaiserslautern

| Surname | Local parish | Remarks | Beginning | The End | location | image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pits near ore smelters | Kaiserslautern , OT Erzhütten | Iron; extensive ping field; before the 18th century; 400 m wide field, in north-south. Direction located between | location | |||

| Pits near Kaiserslautern | Kaiserslautern | Iron; extensive ping field; before the 18th century; nowadays largely overbuilt | Location (approx.) |

Lviv

Mining on Mount Lemberg dealt primarily with mercury.

| Surname | Local parish | Remarks | Beginning | The End | location | image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Catherina | Feilbingert | Mercury; The mining license was issued in 1774, Mutung was in 1775, and was operated until around 1792 | 1775 | 1792 | location | |

| Three moves | Niederhausen | Mercury; Consolidation from St. Martins Zug , Loyalty Confidence and Schmittenstollen ; 15 km track and tunnel length | ||||

| Geiskammer | Feilbingert | Mercury and coal; in the Bavarian state forest in the Oberhauser Eck department; first mentioned in 1469; first loan in 1730 to search for coal to supply the laboratories of the Niederhausen mines, mercury ore was also found and mined from 1760. Mercury mining ended for the time being 6 years later, resumed from 1770 to 1775; no significant production rates are known. From 1783 onwards under the name of Grube Ernesti Glück , unsuccessful, and finally shut down from 1795. Coal mining continued with short interruptions until 1796. | 1469 | 1795 | location | |

| In the iron hedge | Feilbingert | Hard coal; west of the former district of Feil | ||||

| Johannes Stollen | Niederhausen | Search tunnel for mercury; was in work in 1790 and again briefly around 1850, no significant dismantling | 1790 | 1850 (um) | location | |

| Lviv | Niederhausen | Mercury; Pit field; awarded on May 12, 1837; renounced on September 25, 1840; unsuccessful experimental work | 1837-05-12 | 1840-09-25 | ||

| Kellerberg | Weinheim | Mercury; Grubenfeld near Weinsheim (a little north of the Lembergs and north of the Nahe); awarded on May 12, 1837; renounced on September 25, 1840; unsuccessful experimental work | 1837-05-12 | 1840-09-25 | ||

| Schmittenstollen | Niederhausen | Mercury; up to 100 employees; Karlsglückstollen; Machine shaft with a depth of 60 m; Hours of operation: 15th century - 1632, 1728–1818, 1935–39 | 1438 | 1942 | location |

|

| St. Martin's train | Niederhausen | Mercury; from the 15th century with interruptions until 1936, together with the Schmittenzug (now the Schmittenstollen visitor mine ) and the Treue Zuversicht Zug, the three trains that are connected to each other | 15th century | location | ||

| stollen | Niederhausen | Tunnels cut by a more modern quarry; Age unknown | location | |||

| Loyalty Confidence | Niederhausen | Mercury; from the 15th century with interruptions until 1936, formed together with the Schmittenzug (now the Schmittenstollen visitor mine ) and the St. Martins Zug, the three trains connected to each other ; 20 employees | 15th century | location |

Upper moschel

| Surname | Local parish | Remarks | Beginning | The End | location | image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pits on the Landsberg | Upper moschel | Silver and later mercury ( cinnabar ); numerous opencast mines and shaft pings, which indicate mining for silver before 1442, then mainly mercury mining from the 15th century | 1442 (before) | location | ||

| Pits on the Seelberg | Niedermoschel | Silver, lead, copper; probably from 1429 | 1429 | location |

Potzberg

Mining on the Potzberg mountain and the immediate vicinity mainly dealt with mercury.

| Surname | Local parish / district | comment | location |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elisabeth pit | Foeckelberg | Mercury; Started in 1771, field allocation 1773, remained in operation with interruptions until 1860; After a break of almost 20 years, the two pits Elisabeth and Klopwald / Hutschbach were merged with the new name Rudolphs Segen in 1879, and the operation was finally abandoned a short time later due to insufficient yield. | location |

| Kloppwald and Hutschbach experimental pit | Foeckelberg | Mercury; Started in 1777, muted in 1781, merged with Elisabeth-Grube in 1879, end of operation in the 1880s | location |

| Free will experimental pit | Foeckelberg | Mercury; Started in 1774, only in operation for a few years, renewed in 1781, was in operation after 1788, before 1850 combined with the Drei Kronen-Zug mine | location |

| Pit Three Crown Train | Foeckelberg | Mercury; Begun in 1776, merged with Grube Freier Wille before 1850 | location |

| Pit Three Kings Train | Mühlbach | Mercury; Started in 1776, was the largest and most famous company, closed in 1865/1866; in 1805 14,187 kg of mercury were produced; had two tunnels for water removal, the upper tunnels were driven from 1780 to 1798 and began at the Mühlbach, the lower tunnels started in 1842; The mine was reopened in 1879 under the new name Drei Königs-Zeche, but it was no longer dismantled; renewed, equally unsuccessful attempts around 1907. | location |

| Pit help of god | Mühlbach | Mercury; Started in 1774, still in operation in 1788, merged with Grube Drei Königs-Zug before 1850 | location |

| Martin's pit | Mühlbach | Mercury; Started in 1778, still in use in 1788 | location |

| Experimental gallery Drei Mohren-Zug | Mühlbach | Mercury; Started in 1777 | location |

| Fresh courage experimental pit | Föckelberg and Mühlbach | Mercury; Begun in 1774, merged with the Drei Königs-Zug pit in 1807 | location |

| St. Paulus train pit | Mühlbach | Mercury; Started in 1775, in operation in 1788 | location |

| Pit New Hope | Mühlbach | Mercury; Started in 1779, two small studs, not long in operation | location |

| Herchenloch pit | Foeckelberg | Mercury; Started in 1773, several new mining permits until 1786, d. H. the pit was briefly in operation several times. | location |

| Pit Three Wise Men Train | Mühlbach | Mercury; single excavation tunnel , started in 1775 | location |

| Baron Friedrich pit | Foeckelberg | Mercury; several small excavation tunnels, finished before 1788 | location |

| Joseph's crown pit | Foeckelberg | Mercury; Started in 1774; two tunnels, finished before 1788 | location |

| St. Christian pit | Foeckelberg | Mercury; Begun in 1774 | location |

| Vogelacker mine | Foeckelberg | Mercury; Started in 1774, after 1788 merged with the neighboring Antoni Hilfe mine | location |

| Pit blessings of god | Foeckelberg | Mercury; Started in 1774, only in operation for a short time | location |

| Pit flat train | Mühlbach | Mercury; Begun in 1779, abandoned in 1783 | location |

| Pit Carl's luck | Mühlbach | Mercury; Begun in 1776, abandoned in 1783 | location |

| Pit Johannes Blessing | Mühlbach | Mercury; Begun in 1778 | location |

| Dorothea and Philipps Pit | Föckelberg, Mühlbach and Rutsweiler | Mercury; Begun in 1778/79 | location |

| St. Peters-Zug pit | Rutsweiler | Mercury; Only in operation for a short time, abandoned in 1784 | location |

| Pit Mary Help | Rutsweiler | Mercury; Begun in 1778, abandoned in 1786 | location |

| Pit luck | Rutsweiler | Mercury; also called soup bowl; started before 1779 | location |

| Birkenhübel gallery | Rutsweiler | Mercury; Begun in 1782, abandoned in 1783 | location |

| Altenkopfer Schurfwerk | Theisbergstegen | Mercury; begun in 1782 | location |

| Jakobsburg mine | Theisbergstegen | Mercury; Begun in 1775 | location |

| Wildenburg mine | Theisbergstegen | Mercury; Begun in 1775 | location |

| Schurf salt lick | Neunkirchen | Mercury; Started in 1779, two short operating times | location |

| David's Crown Pit | Foeckelberg | Mercury; Started in 1782, with interruptions in operation until 1860, repeated attempts in 1879, which were unsuccessful | location |

| Sebastian's pit | Foeckelberg | Mercury; Started in 1782; several short operating phases | location |

| Pottaschhütte mine | Föckelberg and Rutsweiler | Mercury; Begun in 1780 | location |

| Alter Potzberg mine | Gimsbach | Mercury, sulfur, iron vitriol; oldest mine in the Potzberg mining area, started in the first half of the 18th century, possibly even older, the first operating phase ended in 1747, iron vitriol was produced in a separate vitriol factory; the second operating phase ran from 1767 to 1793; many opencast mines and shallow tunnels, no deep mine buildings; In modern literature, the mine is ascribed a 1,100 m long tunnel, neither in the literature from that time nor in the area can any evidence of this tunnel be found. | location |

| Mine, Zahnsche experiment | Neunkirchen | Mercury; Mine tunnel, derelict before 1788 | location |

| Jakobsburg mining tunnel | Neunkirchen | Mine shaft, abandoned before 1788 | location |

| Mine Jacob's blessing | Neunkirchen | Mine shaft, abandoned before 1788 | location |

| Water super try | Foeckelberg | Mine shaft, abandoned before 1788 | location |

| Faulborn experimental tunnel | Foeckelberg | Experimental tunnel, abandoned before 1788 | location |

Potzberg (mining works)

In the region around the Potzberg, numerous small excavation pits and search works for mercury ores were operated in the 18th century, which are known from mining permits. The operation was only small in scope, mostly for a short time, and remained close to the surface.

Able able able able able able able able able able able able able able able able able able able able able able able able able able able able able able able able able able able able able able able able able able able able able able able able able able location location location location location location location location location location location location location location location location location location location location location location location location location

Stahlberg

At Stahlberg and the neighboring areas, mercury ores were mined as early as the early 16th century.

| Surname | Local parish | comment | location |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pingenfeld | Stahlberg | Silver; larger field with numerous, closely spaced shaft pings, dated to the 14th century by ceramic finds; This is where the Stahlberger mining began. | location |

| Silver mine | Stahlberg | Pale ores (silver), mercury (cinnabar) increased from the 16th century; early mining, first mentioned in 1513, in 1732 the pits were still in operation. | location |

| Silver mine | Stahlberg | see above | location |

| Silver mine | Stahlberg | see above | location |

| Silver mine | Stahlberg | see above | location |

| Silver mine | Stahlberg | see above | location |

| Silver pits | Stahlberg | see above | location |

| Silver mine | Stahlberg | see above | location |

| Silver mine | Stahlberg | see above | location |

| Silver mine | Stahlberg | see above | location |

| Archangel Michael Pit | Stahlberg | Mercury, predominantly cinnabar; built in the area of the two silver ore mining pits, which were operated until the beginning of the 16th century, Kleiner and Großer Hattenberg, the main operating period began after 1728, later merged with the St. Philipp mine, active with brief interruptions until 1850, then again from 1934 to 1942; the three pits Archangel Michael, St. Philipp and Bergmannsherz were the largest and most exploitable pits on the Stahlberg . | location |

| Archangel Michael Pit | Stahlberg | see above | location |

| Archangel Michael Pit | Stahlberg | see above | location |

| Archangel Michael Pit | Stahlberg | see above | location |

| Archangel Michael Pit | Stahlberg | see above | location |

| Archangel Michael Pit | Stahlberg | see above | location |

| Archangel Michael Pit | Stahlberg | see above | location |

| Archangel Michael Pit | Stahlberg | see above | location |

| Archangel Michael Pit | Stahlberg | see above | location |

| St. Philipp pit | Stahlberg | Mercury, predominantly cinnabar; shortly after the opening, operated in association with the Archangel Michael mine; the three pits Archangel Michael, St. Philipp and Bergmannsherz were the largest and most exploitable pits on the Stahlberg. | location |

| St. Philipp pit | Stahlberg | see above | location |

| St. Philipp pit | Stahlberg | see above | location |

| St. Philipp pit | Stahlberg | see above | location |

| St. Philipp pit | Stahlberg | see above | location |

| Pit miner's heart | Stahlberg | Mercury, predominantly cinnabar; based on earlier pits, Bergmannsherz was approached again in the second quarter of the 18th century and was also active during the last operating period on the Stahlberg from 1934 to 1942; the three pits Archangel Michael, St. Philipp and Bergmannsherz were the largest and most exploitable pits on the Stahlberg. | location |

| Pit miner's heart | Stahlberg | Mercury, mostly cinnabar | location |

| Pit miner's heart | Stahlberg | Mercury, mostly cinnabar | location |

| Pit miner's heart | Stahlberg | Mercury, mostly cinnabar | location |

| Prince Friedrich's pit | Stahlberg | Silver and mercury; also called Count Friedrich; In the 15th or 16th century operations were started (for silver), but stopped relatively quickly due to a shortage of ore. In the middle of the 18th century, the mining of mercury began, which lasted intermittently until around 1850, in the last period on Stahlberg from 1934 to 1942 there were only a few test digs, operations were no longer started. | location |

| Prince Friedrich's pit | Stahlberg | see above | location |

| Prince Friedrich's pit | Stahlberg | see above | location |

| Prince Friedrich's pit | Stahlberg | see above | location |

| Prince Friedrich's pit | Stahlberg | see above | location |

| Prince Friedrich's pit | Stahlberg | see above | location |

| Pit freshness courage | Stahlberg | Mercury, predominantly cinnabar; Started in the early 18th century in older mine works, merged with the St. Peter mine in 1758, operation until a few years after 1848 | location |

| Pit freshness courage | Stahlberg | see above | location |

| Pit freshness courage | Stahlberg | see above | location |

| Pit freshness courage | Stahlberg | see above | location |

| Pit freshness courage | Stahlberg | see above | location |

| Pit freshness courage | Stahlberg | see above | location |

| St. Peter's Pit | Stahlberg | Mercury, predominantly cinnabar; Started in the early 18th century in older mine workings, united with Grube Fresh Courage in 1758, operation until a few years after 1848 | location |

| St. Peter's Pit | Stahlberg | Mercury, mostly cinnabar | location |

| Pit God's gift | Stahlberg | Mercury, predominantly cinnabar; Started in the middle of the 18th century, in operation until 1848 | location |

| Pit God's gift | Stahlberg | see above | location |

| Pit God's gift | Stahlberg | see above | location |

| Roßwald pit | Stahlberg | Pale ores (silver) and mercury; Beginning before 1560 (on silver), provisional closure around 1600, re-commissioning only around 1776, with brief interruptions until the 1840s, again in 1932, but the attempts remained unsuccessful due to a lack of ore. | location |

| Roßwald pit | Stahlberg | see above | location |

| Roßwald pit | Stahlberg | see above | location |

| Roßwald pit | Stahlberg | see above | location |

| Roßwald pit | Stahlberg | see above | location |

| Roßwald pit | Stahlberg | see above | location |

| Roßwald pit | Stahlberg | see above | location |

| Roßwald pit | Stahlberg | see above | location |

| Roßwald pit | Stahlberg | see above | location |

| Roßwald pit | Stahlberg | see above | location |

| Roßwald pit | Stahlberg | see above | location |

| Roßwald pit | Stahlberg | see above | location |

| Käthchen shafts | Stahlberg | Silver and mercury; Started in the 16th century after a long interruption from 1802 onwards, mainly search tunnels, little mining | location |

| Käthchen shafts | Stahlberg | see above | location |

| Käthchen shafts | Stahlberg | see above | location |

| Digging | Stahlberg | location | |

| Digging | Stahlberg | for ore search, date of origin unknown | location |

| Digging | Stahlberg | for ore search, date of origin unknown | location |

| Stollwald mining works | Stahlberg | Created around 1775 | location |

| Pit Pit Karl Glück | Stahlberg | Started around 1775, with a short operating time | location |

| Carolina Pit | Stahlberg | Sulfur ores for alum and vitriol production; also called sulfur pit; Operation before 1556 until after 1612, again for a short time from 1756 | location |

| Carolina Pit | Stahlberg | see above | location |

| Carolina Pit | Stahlberg | see above | location |

| Karls tunnel | Stahlberg | deepest tunnel for the Stahlberger pits; Started in the middle of the 18th century, but soon given up, work continued from 1792, breakthrough in the Frischer Mut / St. Philipp 1824, from 1848 already partially criminal and no longer accessible | location |

| Karls tunnel | Stahlberg | see above | location |

| stollen | Stahlberg | is entered on a map from 1800 | location |

| stollen | Stahlberg | is entered on a map from 1800 | location |

| Digging | Stahlberg | Age unknown | location |

| Digging | Stahlberg | Age unknown | location |

| Digging | Stahlberg | Age unknown | location |

| Digging | Stahlberg | Age unknown | location |

| Digging | Stahlberg | Age unknown | location |

Wolfstein

The majority of the Wolfstein mines were located on the territory of Wolfstein in the Kusel district and the immediately neighboring communities.

| Surname | District | comment | location |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lime mine on Koenigsberg | Wolfstein | Limestone ; until 1967, today a visitor mine | location |

| Mining (iron) | Wolfstein | location | |

| Aschbach pit | Wolfstein | Barite ; started in the late 18th or early 19th century | location |

| Christian's arch joy pit | Wolfstein | Schachtpingen | location |

| Barite pit | Wolfstein | Barite | location |

| Excavation tunnel | Wolfstein | Age unknown | location |

| Excavation tunnel | Wolfstein | Age unknown | location |

| Palatinate courage pit | Wolfstein | Mercury; Founded in the middle of the 18th century under the name Grube Bruderhorn, from 1773 new beginning under the name Pfälzer Muth; preliminary end of operation around 1800; Subsequently, until 1846, repeated attempts and overhauls without funding; Reopening of operations in 1879 under the name of Grube Einheit (hope for the mines Archangel, Palatinate Hope and Palatinate Courage), shortly thereafter end of operation without renewed extraction; In 1937 the mines were reopened, this time with the aim of extracting iron ore, but the work that had been going on until 1941 was unsuccessful due to the poor quality of the ore.

Pit building with three levels (as of 1797): the upper level was opened before 1797, the middle level was built 18 m lower, with a length of 108 m, in 60 m depth is the lower level with a tunnel length of 404 m, from the lower At the bottom, a cavity 24 m was sunk. |

location |

| Pit Christian's luck | Wolfstein | Mercury; started before 1750, abandoned a few years later; re-muted before 1774 and started operations; 1776 united with the pit of Theodors Erzlust, built on three veins with a thickness of 16 to 50 cm; connected to Theodors Erzlust on the (upper) 20 m level; the second level was 68 m deep and 300 m long; Annual production in the 1780s 47 myriagram (470 kg) pure mercury; own laboratory with furnace for 22 retorts | location |

| Pit Theodor's ardor | Wolfstein | Mercury; largest and most famous mine near Wolfstein; started before 1725, a few years later the operation was stopped again, from 1748 again operation, 1776 union and breakthrough to the pit Christian's luck; by 1791 the Elias tunnel was driven, which ran from the pits in the direction of the Kerstendeicher valley; Expansion of the mining fields in 1841; provisional end of operation in 1860; new courage 1879, together with the Gottelborn mine, the new unified mine is called the Unity Mine, there were only investigations and work-ups, but no funding; renewed attempts from 1934, likewise unsuccessful; a stamping mill was located in the Bocherig area below the pit, it was operated with water from the Laufhauser Weiher; Below the stamp mill was the Laufhausen miners' settlement, now a desert.

For the time it was an unusually large and deep pit building with three levels: the upper one at 20 m depth and 200 m length, the middle one at 60 m depth and 400 m length, the lower one at 136 m depth and 740 m long; the mine had its own laboratory with a retort furnace for 30 retorts to extract the metallic mercury from the ore on site. |

location |

| Gottelborn mine | Wolfstein | Mercury; Started in 1774, operating with several interruptions until the 1780s; then union with Grube Theodors Erzlust | location |

| Winkelbach mine | Wolfstein | Mercury; Started in 1774; further tunnels older than 1774 on this mine field | location |

| Experimental tunnel | Wolfstein | location | |

| Gold mine | Wolfstein | Mercury, sulfur (gold); also called water grinder; Started on mercury in 1778, discontinued after some time, restarted in 1787, which lasted only a short time; From 1800 the mine was reopened with the intention of extracting gold from the iron sulphide ore, but this failed and an attempt was made to sell the iron sulphide. | location |

| Stollen at the Schulfraurech | Wolfstein | Excavation tunnel, not in operation for a long time, no known extraction | location |

| Tauchentaler Mutwerk mine | Wolfstein | Mercury; Begun in 1774 | location |

| Palatinate Hope Pit | Wolfstein | Mercury; First opened before 1773, new beginning from 1773 | location |

| Pit help of god | Wolfstein | Mercury; Digging started in 1775 and ended around 1787; renewed attempt in 1879 as a unified pit Eintracht (Pits Archangel, Palatinate Hope and Palatinate Courage) | location |

| Carl Ludwig's Erzlust (St. Jakob) | Wolfstein | Mercury; Started in 1775, merged with the neighboring St. Georg pit from 1778, new name St. Jakob and St. Georg pit; In the 1780s, the new Carl Ludwigs Erzlust mine existed in the same place. | location |

| Carl Ludwigs Erzlust (St. Georg) | Wolfstein | Mercury; Started in 1774; for more see St. Jakob pit | location |

| Stollen Archangel | Wolfstein | Mercury; Trial tunnel started in 1774; In 1879 went to Grube Eintracht with others | location |

| Johannes Ludovici mine | Wolfstein | Mercury; Started in 1774; also called pit Gebück; only in operation for a short time, then abandoned | location |

| Tunnel (Borndeller Trial) | Wolfstein | location | |

| Herrenpitz mine | Wolfstein | Mercury; also called Neidhardt's work; Started in 1774, only in operation for a short time; 1780 and 1787 two more attempts, without success; abandoned in the 1790s | location |

| Oberkindsbach pit | Wolfstein | Mercury; Started in 1773, soon abandoned; Repeated attempts in 1775 and 1782, without success | location |

| Bendelhecker mine trial | Wolfstein | Mercury; Begun in 1773 | location |

Other regions

| Surname | City / municipality | comment | location | image |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pit near Marienthal | Dannenfels , Marienthal | Copper; several shaft penguins, weak mineralization in the rhyolite | location | |

| Pits near Göllheim | Goellheim | Copper, seam-like ore layers in the Rotliegend, between 1915 and 1917 more than twelve up to 26 m deep round shafts were examined here, the actual number is significantly higher; Mining from Roman times (2nd and 3rd centuries AD); In addition, some narrow tunnels and remains of a Roman plant for desulphurisation and roasting of the ores. | location | |

| Opencast mines near Göllheim | Goellheim | Copper; in the win at the copper holes ; Mixture of individual shafts and large-scale open-cast mining activities up to a depth of 5 m from Roman times; in the 1950s the area was leveled, destroying most of the mining equipment. | location | |

| Pit near Jettenbach | Jettenbach , on the Potzberg | iron | ||

| Pits near Eisenberg | Eisenberg | Iron; most extensive iron production in Roman times; Beginning in the 1st century AD; Smelting slag can sometimes reach a thickness of 4 m | Location (approx.) | |

| Pits near Eisenberg | Eisenberg | Iron; in the area of the late Roman Burgus , iron slag and remains of melting furnaces | Location (approx.) | |

| Pits near Eisenberg | Eisenberg | Iron; in the win Bems ; extensive cinder remnants and Roman building remains | Location (approx.) | |

| Riegelstein pit | Eisenberg | Sound ; Started in 1920, closed in 1996; 600 m tunnel, depth approx. 60 m; today a mining museum , see also Erlebniswelt Erdekaut | location | |

| Reindl Stollen | Eisenberg | Volume; Opened in 1957, closed in 1968, until 1997 visitors' mine; subsequently reactivated as the Doris mine in the opencast mine | ||

| Abendthal mine | Eisenberg | Volume; Driven in 1954, still active (operator: Sibelco ), depth 67 m | ||

| Eisenberger Klebsandwerke | Eisenberg | Sticky sand | ||

| Clay pits | Eisenberg basin | Volume; Above and underground mining in the Eisenberg Basin / Hetteleidelheimer Revier; from the 19th century to today; Because of its properties internationally traded, around 1880 there were 129 clay pits in the region. | ||

| Pits near candle home | Candle Home | Iron; two large iron slag mounds; Dated to late Roman times by ceramic remains | location | |

| Pits near Münchweiler | Münchweiler | Iron; large accumulations of iron slag, furnace scraps and ore; dated 12-14th centuries century | location | |

| St. Anna's gallery | Nothweiler | Iron ore with a high manganese content | location | |

| Ramsen mines and smelting | Ramsen | Iron; at least 18 large slag mounds from the 1st century; (6 places west of Bockbach , 3 east.) | location | |

| 4 shafts at Ramsen | Ramsen | Iron; Late Roman, see Ramsen pits and smelting | location | |

| Pits near Waldmohr | Forest black | Iron; Schachtpingen and cinder residue from Roman times | Location (approx.) | |

| Pits near Waldmohr | Forest black | Iron; quite a few shaft pings and several iron slag mounds; Roman or early medieval | Location (approx.) | |

| Nordfeld mine | Forest black | Hard coal | location | |

| Pit good hope | Sankt Goarshausen - Ehrental / Sachsenhäuser Hof | Silver, lead, zinc; the part of the mine on the left bank of the Rhine was mentioned as ancient on November 7th, 1562; known in the 18th century as Constantins-Erzlust , also called Prinzenstein mine ; on the right bank of the Rhine was formerly called Sachsenhausen silver works; not located in the Palatinate (as it is on the right bank of the Rhine), listed here as it is during the main operating time under the responsibility of the Electorate of the Palatinate; 1790 the second largest mine (after the mercury mine Drei Königszug am Potzberg) with rich yield, i.e. profitable with over 100 miners (Knappschaft) |

|

See also

- Map with all coordinates

- List of closed mines in Germany

- List of mines in the Hunsrück

- List of mines in the Eifel

- List of mines in the Taunus

Use this list offline

For mobile and offline use, all coordinates can be downloaded as a KML file or as a GPX file.

literature

- L. Anton Doll: Communications from the Historical Association of the Palatinate. Publishing house of the historical association of the Palatinate, Speyer 1977: Hans Walling: The early mining in the Palatinate. Pp. 15-46.

- Hans Walling: The ore mining in the Palatinate. State Office for Geology and Mining Rhineland-Palatinate, 2005, ISBN 3-00-017820-1 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Walling, 2005, pp. 86–95, object no. 17.

- ^ Wilfried Rosenberger: Description of the Rhineland-Palatinate mining districts. Volume 3, Mining Authority District Bad Kreuznach, Bad Marienberg 1971, pp. 95 and 116.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 86–95, object no. 3 and 4.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 86–95, object no. 9.

- ↑ Walling, 2005, pp. 86–95, object no. 18.

- ↑ Walling, 2005, pp. 86–95, mentioned for object no. 12. Description on information board on site.

- ↑ Information board on site.

- ↑ Bergbau Erlebniswelt Imsbach - Kupferweg II , accessed on September 18, 2014.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 86–95, object no. 12.

- ↑ Walling, 2005, pp. 86–95, object no. 11.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 86–95, object no. 15.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 86–95, object no. 19.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 86–95, object no. 14.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 86–95, object no. 5.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 86–95, object no. 16.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 86–95, object no. 13.

- ↑ Walling, 2005, pp. 86–95, object no. 10.

- ^ On-site information board, published by the State Office for Geology and Mining, Rhineland-Palatinate

- ↑ Walling, 2005, pp. 86–95, object no. 6.

- ^ Wilhelm Silberschmidt: The regulation of the Palatinate mining system. Leipzig 1913, p. 31 ff.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 86–95, object no. 8.

- ↑ a b Eisenbergbau Imsbach on Mineralienatlas.de, accessed on September 18, 2014.

- ^ Walling, 2005, p. 87, Fig. 58a.

- ↑ Bergbau Erlebniswelt Imsbach - closed mines , accessed on September 18, 2014.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 86–95, object no. 29.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Walling, 2005, pp. 86–95, objects no. 29–31.

- ↑ Walling, 2005, pp. 86–95, object no. 32.

- ^ Walling, 1977, p. 47.

- ^ Walling, 1977, p. 37.

- ↑ Walling, 2005, pp. 121–125, object no. 11.

- ↑ Walling, 2005, pp. 121–125, object no. 10.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 121–125, object no. 15.

- ↑ Walling, 2005, pp. 121–125, object no. 5.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 121–125, object no. 6.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 121–125, object no. 19.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 121–125, object no. 7.

- ↑ Ludwig Spuhler: Introduction to the geology of the Palatinate. Speyer 1957, p. 312.

- ^ Walling, 1977, p. 27.

- ^ Wilfried Rosenberger: Description of the Rhineland-Palatinate mining districts. Volume 3, Mining Authority District Bad Kreuznach, Bad Marienberg 1971.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 2.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 3.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 4.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 5.

- ↑ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 6.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 7.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 8.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 9.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 10.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 11.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 12.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 13.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 14.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 15.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 16.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 17.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 18.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 19.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 20.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 21.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 22.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 24.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 25.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 26.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 27.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 28.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 29.

- ↑ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 30.

- ↑ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 31.

- ↑ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 32.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 33.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 34.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 35.

- ↑ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 36.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 37.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 38.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 39.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 40.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 41.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 141.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 139.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 140.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 136.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 137.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 138.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 124.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 146.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 144.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 117.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 145.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 143.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 142.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 130.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 128.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 127.

- ↑ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 147.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 112.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 115.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 116.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 133.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 85.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 135.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 104.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 105.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 100.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 84.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 89.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 77.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 87.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 81.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 97.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 75.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 101.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 80.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 103.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 93.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 96.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 106.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 52.

- ↑ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 113.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 125.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 119.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 120.

- ↑ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 118.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 54.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 64.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 44.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 59.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 53.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 46.

- ↑ a b c d Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no.?

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 62.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 55.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 76.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 69.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 79.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 86.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 95.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 94.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 98.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 83.

- ↑ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 74.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 71.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 92.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 51.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 67.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 61.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 58.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 49.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 63.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 156–167, object no. 66.

- ↑ Walling, 2005, pp. 182-185, Grubenfeld No. 1.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Walling, 2005, pp. 182–185, Grubenfeld No. 2.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Walling, 2005, pp. 182–185, Grubenfeld No. 3.

- ↑ a b c d e Walling, 2005, pp. 182–185, Grubenfeld No. 4.

- ^ A b c d Walling, 2005, pp. 182–185, Grubenfeld No. 5.

- ↑ a b c d e f Walling, 2005, pp. 182–185, Grubenfeld No. 6.

- ↑ a b c d e f Walling, 2005, pp. 182–185, Grubenfeld No. 7.

- ↑ a b Walling, 2005, pp. 182-185, Grubenfeld No. 8.

- ^ A b c Walling, 2005, pp. 182–185, Grubenfeld No. 9.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l Walling, 2005, pp. 182–185, Grubenfeld No. 10.

- ↑ a b c Walling, 2005, pp. 182–185, Grubenfeld No. 11.

- ↑ a b c Walling, 2005, pp. 182–185, Grubenfeld No. 12.

- ↑ Walling, 2005, pp. 182-185, Grubenfeld No. 13.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 182–185, Grubenfeld No. 14.

- ↑ a b c Walling, 2005, pp. 182-185, Grubenfeld No. 15.

- ↑ a b Walling, 2005, pp. 182–185, Grubenfeld No. 16.

- ↑ a b Walling, 2005, pp. 182-185, Grubenfeld No. 17.

- ↑ a b c d e Walling, 2005, pp. 182–185, Grubenfeld No. 18.

- ^ Revier: here in the sense of a geographical location, not an assignment under mining law.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 201–207, object no.?

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 201-207, object no. 33.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 201–207, object no. 31.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 201-207, object no. 34.

- ↑ a b Walling, 2005, pp. 201–207, object no. 32.

- ↑ Walling, 2005, pp. 201-208, object no. 5.

- ↑ a b c C. Beurard: Reports on quelques mines de Mercure situées dans les nouveaux départemens de la rive gauche du Rhin. In: Journal des Mines. Issue 7, numéro XLI pluviose, 1797–1798, pp. 349 ff. Digitized version , accessed on September 25, 2014.

- ↑ Walling, 2005, pp. 201-208, object no. 3.

- ↑ Walling, 2005, pp. 201–208, object no. 2.

- ↑ Walling, 2005, pp. 201–207, object no. 4.

- ↑ Walling, 2005, pp. 201–207, object no. 13.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 201–207, object no.?

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 201-207, object no. 8.

- ↑ Walling, 2005, pp. 201–207, object no. 12.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 201–207, object no. 11.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 201-207, object no. 7.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 201–207, object no. 6.

- ↑ Walling, 2005, pp. 201–207, object no. 9.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 201–207, object no. 10.

- ↑ Walling, 2005, pp. 201–207, object no. 15.

- ↑ Walling, 2005, pp. 201–207, object no. 14.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 201–207, object no.?

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 201-207, object no. 17.

- ↑ Walling, 2005, pp. 201–207, object no. 16.

- ^ Walling, 2005, pp. 201-207, object no. 20.

- ^ Walling, 1977, p. 21.

- ↑ a b Walling, 1977, p. 21 f.

- ^ Friedrich Sprater: The Palatinate Industries in Prehistory and Early History (= local history publications of the Palatinate History Museum). Neustadt 1926, p. 99 ff.

- ^ Walling, 1977, p. 28 f.

- ^ Walling, 1977, p. 35.

- ^ Verbandsgemeinde Eisenberg - Information on Erdekaut ( Memento from October 6, 2014 in the Internet Archive ), accessed on September 24, 2014.

- ↑ a b U. Böhler, M. Böttger, W. Smykatz-Kloss, J.-F. Wagner: Excursion to clay deposits in the Upper Rhine Graben. In: K. A. Czurda, J.-F. Wagner (editor): Tone in der Umwelttechnik (= series of publications applied geology). Universität Karlsruhe, 1988, p. 314, digitized version (PDF), accessed on September 24, 2014.

- ^ Company website ( memento of October 6, 2014 in the Internet Archive ), accessed on September 24, 2014.

- ↑ U. Böhler, M. Böttger, W. Smykatz-Kloss, J.-F. Wagner: Excursion to clay deposits in the Upper Rhine Graben. In: K. A. Czurda, J.-F. Wagner (editor): Tone in der Umwelttechnik (= series of publications applied geology). Universität Karlsruhe, 1988, p. 315, digitized version (PDF), accessed on September 24, 2014.

- ^ Verbandsgemeinde Hettenleidelheim - Information on the clay pits ( memento of October 6, 2014 in the Internet Archive ), accessed on September 24, 2014.

- ^ Sprater, 1929, p. 94.

- ^ Walling, 1977, p. 38 f.

- ↑ Ludwig Gottschall: In the Middle Ages. Iron production at Münchweiler. In: Pirmasenser Zeitung . March 10, 1961.

- ^ Walling, 1977, p. 39.

- ↑ Sprater 1926, p. 7 ff.

- ^ Walling, 2005, p. 195, object no.3.

- ^ Walling, 2005, p. 195, object no. 2.

- ↑ The mine is located across the border between Saarland and Rhineland-Palatinate.

- ↑ Mannheimer Intellektivenblatt - for pleasant and useful maintenance - for the year 1790. Buchdruckerei des Bürgerhospital, 1790, pp. 44 f., P. 132 f. Digitized version , accessed on September 25, 2014.

- ↑ Memorable and useful antiquarian who presents the most important and pleasant geographical, historical and political peculiarities of the whole Rhine river from its outflow into the sea to its origin. Publishing house Rud. Friedr., Hergt., Coblenz 1856, p. 20 ff., Digitized .

- ↑ KML file . Retrieved August 18, 2019.

- ↑ GPX file . Retrieved August 18, 2019.