Population genetics and anthropology of the linear ceramic culture

By means of population genetics or paleogenetics , important connections can be uncovered and questions can be clarified in anthropology . For scientific work in archeology, here on the Neolithic culture of linear ceramicists , genetic and anthropological processes have become important supportive auxiliary science.

Population genetics is a scientific branch of genetics . It deals with the analysis of genetic samples from the remains of organisms , here mainly from the finds of linear ceramic skeletons. The genetic information ( aDNA or DNA fragments) is extracted from the samples , amplified using the polymerase chain reaction and sequenced .

The band ceramists and the question of the ancestors of modern Europeans

The spread of the Linear Band Ceramic Culture (LBK) probably began around 5700 BC. BC - starting from the area around Lake Neusiedl - and created a large, culturally uniform and stable settlement and cultural area within a period of human history of around 200 years . The reconstruction of this cultural unity is based on finds in the areas of today's countries West Hungary ( Transdanubia ), Romania , Ukraine , Austria , South West Slovakia , Moravia , Bohemia , Poland , Germany and France (here under the name culture rubanée: Paris Basin , Alsace and Lorraine ) . Accordingly, the LBK is considered the largest area culture of the Neolithic .

A possible division of the LBK into epochs is:

- around 5700/5500 to around 5300: oldest LBK

- around 5300 to 5200: average LBK

- around 5200 to 5000: younger LBK

- around 5100 to 4900: youngest LBK (overlaps with younger LBK)

Two models are primarily discussed for the process of Neolithization in Southeastern and Central Europe:

- cultural diffusion: Appropriation of cultural techniques ( culture transfer , acculturation ) by the local late Mesolithic population (compare diffusionism and cultural diffusion ) - the Neolithic developed out of the local Mesolithic population and knowledge of agriculture, cattle breeding and the associated technologies came from the Middle East from from one indigenous group to the next without any fundamental migration of human groups

- demic diffusion : immigration of groups from the Middle East - the bearers of the band ceramic culture were not members of or descendants of the post-glacial , Mesolithic indigenous hunters and gatherers ; the spread of the Neolithic (Neolithic) was based on population growth with spatial expansion of agricultural communities or entire societies.

If the band ceramics had their origin in the Starčevo - Körös culture or in an Anatolian culture , which gradually spread in a north-westerly direction, along the rivers, to Central Europe - taking into account the general, low population or settlement density - then must one speculates that the Mesolithic locals, with their more than 30,000 years of independent cultural development, and that of the immigrants, maintained their respective differences. It must also be assumed that the members of the two population groups spoke different languages.

The diffusionists , who see the appropriation of cultural techniques by the local late Mesolithic population, admittedly admit a migration to the Middle East or Europe, but see in the band ceramists the descendants of Mesolithic hunter-gatherers who would have taken over the "agricultural package". Then the different language areas that come into contact with one another should have enabled the complex cultural transfer via language contact . Such an exchange can have taken place through direct close or long-distance contacts between representatives of the ethnic groups who have access to the agricultural techniques, whereby by long-distance contacts one understands relationships that do not take place through spatial proximity in the immediate home, but z. B. take place through trade relationships.

Genetic Studies

The old European, Mesolithic hordes of the hunter-gatherer cultures preferred to carry the mitochondrial haplogroups U4 and U5 , which have not yet been found in linear ceramics. The haplogroup U4 is widespread in the populations of the Upper Paleolithic . This period describes the more recent part of the Eurasian Paleolithic from 40,000 years to the end of the last glacial period (beginning of the Holocene ) around 9,700 BC. Chr. The beginning of the Upper Paleolithic is immigration "anatomically modern man" ( Homo sapiens ) to Europe.

The band ceramics - according to the current state of research - left only very little traces in the gene pool of Europeans. The scientific interpretations of the results found with regard to the genetic distribution of special haplotype variations in the ceramic band cultures are still very much in flux. According to Wolfgang Haak (2006), the mitochondrial haplotype distribution in the area of ribbon ceramics is divergent, so influences from several directions meet in the range of their culture in the samples examined throughout Central Europe. In the western European area of distribution of the band ceramics mainly the mitochondrial haplotype V , T and K can be found , in contrast in central Germany , besides the mentioned ones, there are also the mitochondrial haplotypes Hgs N1a, W , HV.

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA)

Investigations of the mitochondrial DNA from bone material by the linear ceramicists at the Institute for Anthropology at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz showed that the genetic influence of the first Neolithic farmers on modern Europeans is minimal. Accordingly, predominantly the Paleolithic inhabitants of the continent can be regarded as our biological ancestors in Central Europe. Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) represents separate genetic information that is only passed on in the female reproductive line and is located outside the chromosomal and diploid cell nucleus.

The band ceramic immigrants showed a different gene distribution than most Europeans today; they showed the haplogroups most commonly N1a or H on. In contrast to variant H, which is very common, the N1a variation is only found very rarely today. However, it occurs mainly on the Arabian Peninsula as well as in Tanzania, Kenya, Ethiopia and Egypt. They were also found in Central Asia and South Siberia.

The variants of the haplogroup H , as they are more often found in the band ceramics, include the genes such as H16, H23 and H26 - these are rarely found in the recent population - or also H46b, H88 and H89, which are almost no longer found today can be found. The haplogroup variant N1a comes from the Middle East and appeared 12,000 to 32,000 years ago. The Arabian Peninsula in particular is viewed as the geographical origin of the N1a variation. This hypothesis is supported by the relative abundance and genetic diversity of N1a in the recent population of this region.

In summary, in the publication or investigation period from 2005 to 2013, "linear ceramic sequences" were detected in the mitochondrial haplogroup spectra, consisting of - in different frequencies - N1a, T2, K , J , HV, V , W , X and H in 102 exposed individuals been.

Y chromosome haplogroup

By examining the haplogroup of the Y chromosome , the common ancestors can be traced in a purely male lineage, because the Y chromosome is always passed on from father to son. The band ceramists mostly belonged to haplogroup G2a (Y-DNA) , haplogroup H2 (Y-DNA) and haplogroup T1a1 (Y-DNA) . In particular, the haplogroup G2a (Y-DNA) was detected on the Saxony-Anhalt grave fields of Halberstadt and Derenburg , the haplogroup H2 (Y-DNA) on the Saxony-Anhalt grave field of Derenburg and the haplogroup T1a1 (Y-DNA) on Saxony -anhaltischen burial ground of Karsdorf .

Haplogroup branches can be used to generally show how population groups have moved on earth. Haplogroups can thus also define a geographical area. Older haplogroups are larger and more widespread, and numerous younger subgroups are derived from them.

Anthropological characteristics

Assuming that the shape of a human body is the result of growth processes as well as ways of maintenance or nutrition that are subject to a variety of influencing factors, the result can be on the one hand with genetically determined and on the other hand with the living environment ( cultural area ), such as the climate Explain physical demands, the type of production of goods, diseases and infections etc. to certain conditions. Although the recent findings vary in many places (between a more robust to a more delicate type), from an anthropological point of view, a trend towards the gracefulization of the skeletons and the leptodolichomorphism of the cranial skeleton emerges for the figure within the Central European " population of ceramicists" . The grace is an expression of the decrease in bone size and coarseness. The Neolithics are smaller in body size than the Mesolithics living at the same time, who are broad-faced, low-faced and broad-nosed (compare human brachycephaly ).

According to Tiefenböck (2010), who carried out an investigation of linear ceramic skeletal remains from Kleinhadersdorf in Lower Austria , the height of the men varied between 156.5 and 175.5 cm, with the average height being 166.6 cm. The estimated height of the women, which could only be determined in two individuals, was 156 cm and 160 cm.

Web links

- The genetic origins of Europeans. Researchers compare the genomes of original hunters and gatherers as well as early farmers with those of today's humans: the traces of the Europeans lead to ancestors from three populations. September 17, 2014, University of Tübingen / CS Research ( [4] on archaeologie-online.de).

literature

General overviews

- Elsbeth Bösl: Doing Ancient DNA: On the history of science of aDNA research. transcript Verlag, Bielefeld 2017, ISBN 978-3-8394-3900-5

Special literature on LBK

- Barbara Bramanti, Joachim Burger u. a .: Genetic Discontinuity Between Local Hunter-Gatherers and Central Europe's First Farmers. In: Science. Volume 326, No. 5949, October 2, 2009, pp. 137-140 (English; ISSN 0036-8075 ; doi: 10.1126 / science.1176869 ).

- J. Burger, M. Kirchner et al. a .: Absence of the Lactase-Persistence associated allele in early Neolithic Europeans. In: Proceedings of the National Academy of Science USA. No. 104, 2007, pp. 3736-3741 (English; ucl.ac.uk PDF).

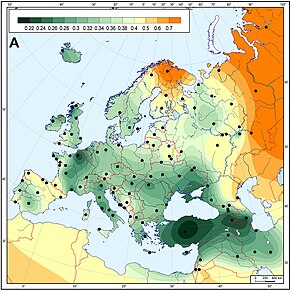

- Joachim Burger , Detlef Gronenborn, Peter Forster, Shuichi Matsumura, Barbara Bramanti, Wolfgang Haak: Response to Comment on “Ancient DNA from the First European Farmers in 7500-Year-Old Neolithic Sites”. In: Science. Volume 312, No. 5782, June 30, 2006, p. 1875b, Figure 1 (English; doi: 10.1126 / science.1123984 ); Quote: "The colors indicate time scales for the spread of the early Neolithic in Europe. All 24 samples of our ancient DNA study belong to the same LBK / AVK (Linear pottery and Alföld linear pottery culture) chronostratum, representing the first farmers in much of central Europe. "

- Thorwald Ewe: Europe's enigmatic ancestors. In: Image of Science. No. 2, 2011, p. 68: Culture & Society. ( online ( memento of July 15, 2014 in the Internet Archive )).

- Michael Francken: Family and Social Structures - Anthropological Approaches to the Internal Classification of Linear Pottery Populations in Southwest Germany. Dissertation by Eberhard Karls University of Tübingen, Senckenberg Center for Human Evolution and Paleoenvironment, Tübingen 2016 ( [5] on publications.uni-tuebingen.de)

- Cristina Gamba, Eppie R. Jones, Matthew D. Teasdale, Russell L. McLaughlin, Gloria Gonzalez-Fortes, Valeria Mattiangeli, László Domboróczki u. a .: Genome flux and stasis in a five millennium transect of European prehistory. In: Nature Communications. No. 5, Article No. 5257 ( doi: 10.1038 / ncomms6257 ; nature.com ).

- Wolfgang Haak: Population genetics of the first farmers in Central Europe. An aDNA study on Neolithic skeletal material. Dissertation, University of Mainz 2006 ( PDF ( Memento from October 29, 2013 in the Internet Archive )).

- Wolfgang Haak, Oleg Balanovsky u. a .: Ancient DNA from European Early Neolithic Farmers Reveals Their Near Eastern Affinities. In: PLoS Biology. Volume 8, No. 11, November 9, 2010, pp. 1-16, online: pp. E1000536 (English; doi: 10.1371 / journal.pbio.1000536 ).

- Wolfgang Haak, Peter Forster u. a .: Ancient DNA from the First European Farmers in 7500-Year-Old Neolithic Sites. In: Science. Volume 310, No. 5750, November 11, 2005, pp. 1016-1018 (English; doi: 10.1126 / science.1118725 ; PDF: 212 kB, 3 pages on uni-mainz.de ( Memento from August 28, 2017 on the Internet Archives )).

- Marie Lacana, Christine Keyser u. a .: Ancient DNA reveals male diffusion through the Neolithic Mediterranean route. In: PNAS. Volume 108, No. 24, June 14, 2011 (English; pnas.org PDF).

- Jens Lüning: Some things fit, others don't: the state of archaeological knowledge and results of DNA anthropology for the early Neolithic. ( Memento from November 7, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Archaeological Information, Early View DGUF Conference Erlangen 2013, pp. 1–10.

- M. Metspalu, T. Kivisild, E. Metspalu, J. Parik, G. Hudjashov, K. Kaldma, P. Serk, M. Karmin and others. a .: Most of the extant mtDNA boundaries in south and southwest Asia were likely shaped during the initial settlement of Eurasia by anatomically modern humans. In: BMC Genetics. 5, 2004, p. 26, doi: 10.1186 / 1471-2156-5-26 , PMC 516768 (free full text). PMID 15339343 .

- Malliya Gounder Palanichamy, Cai-Ling Zhang, Bikash Mitra1, Boris Malyarchuk, Miroslava Derenko, Tapas Kumar Chaudhuri, Ya-Ping Zhang: Mitochondrial haplogroup N1a phylogeography, with implication to the origin of European farmers. In: BMC Evolutionary Biology. No. 10, 2010, p. 304 ( biomedcentral.com PDF).

- Christoph Rinne, Ben Krause-Kyora: Genetic analysis on the multi-period grave field of Wittmar, Ldkr. Wolfenbüttel. In: Archaeological Information, Early View. DGUF conference Erlangen 2013, pp. 1–9 ( PDF: 2.8 kB, 9 pages on uni-heidelberg.de).

- Barbara Elisabeth Tiefenböck: The pathological changes to the linear ceramic skeleton remains from Kleinhadersdorf, Lower Austria - an anthropological contribution to the reconstruction of living conditions in the early Neolithic. Master's thesis in natural sciences at the University of Vienna 2010 ( PDF: 18 MB, 193 pages on univie.ac.at).

Individual evidence

- ↑ Before Present is an age given to English before present "before today" and is used for uncalibrated 14 C data needed

- ^ T. Douglas Price, Joachim Wahl a. a .: The ceramic burial ground of Stuttgart-Mühlhausen: New research results on migration behavior in the early Neolithic (= Find reports Baden-Württemberg. Volume 27). Published by the State Office for Monument Preservation in the Stuttgart Regional Council. Konrad Theiss, Stuttgart 2003, pp. 23–58 ( online at researchgate.net; PDF: 454 kB, 36 pages at discovery.ucl.ac.uk).

- ↑ Hans-Christoph Strien: Settlement history of the Zabergäus 5500-5000 BC Chr. Special print from: Christhard Schrenk, Peter Wanner (ed.): Heilbronnica 5 - Contributions to the city and regional history Sources and research on the history of the city of Heilbronn. No. 20 (= yearbook for Swabian-Franconian history. Volume 37). Stadtarchiv Heilbronn, 2013, pp. 35–50 ( PDF: 932 kB, 17 pages at stadtarchiv.heilbronn.de).

- ^ Eva Lenneis, Peter Stadler: On the absolute chronology of linear ceramic tape based on 14 C data. In: Archeology of Austria. Volume 6, No. 2, pp. 4–13 ( full page on winserion.org).

- ^ The Genographic Consortium, Alan Cooper: Ancient DNA from European Early Neolithic Farmers Reveals Their Near Eastern Affinities . In: PLOS Biology . 8, No. 11, November 9, 2010, ISSN 1545-7885 , p. E1000536. doi : 10.1371 / journal.pbio.1000536 . PMID 21085689 . PMC 2976717 (free full text).

- ↑ Silviane Scharl : The Neolithization of Europe - Models and Hypotheses. Archaeological Information 26/2, (2003) 243–254 ([ https://journals.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/index.php/arch-inf/article/download/12660/6495 ] on journals.ub.uni -heidelberg.de) here p. 246 f.

- ↑ Wolfram Schier: Extensive fire cultivation and the spread of the Neolithic economy in Central Europe and Southern Scandinavia at the end of the 5th millennium BC Chr. Praehistorische Zeitschrift 84 (1): 15-43, January 2009 ( [1] on researchgate.net) here pp. 16-17

- ↑ A. Ammerman, L. Cavalli-Sforza: The Origins of Agriculture. P. 9-33 In: Albert J. Ammerman, Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza (Ed.): The Neolithic Transition and the Genetics of Populations in Europe. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey 1984 doi: 10.2307 / j.ctt7zvqz7.7

- ↑ see also wave of advance model by Ammerman AJ, Cavalli-Sforza LL (1984), Sjödin P., François O .: Wave-of-Advance Models of the Diffusion of the Y Chromosome Haplogroup R1b1b2 in Europe. PLoS ONE 6 (6) (2011) doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0021592 ( [2] on journals.plos.org)

- ↑ Ivo Hajnal : Historical-Comparative Linguistics, Archeology, Archeogenetics and Glottochronology. Can these disciplines be combined sensibly? In: Wolfgang Meid (Ed.): Archaeological, Cultural and Linguistic Heritage: Festschrift for Erzsébet Jerem in Honor of her 70th Birthday. Archaeolingua Alapítvány, Budapest 2012, ISBN 978-963-9911-28-4 , pp. 265–282.

- ↑ Harald Haarmann: In the footsteps of the Indo-Europeans: From the Neolithic steppe nomads to the early advanced civilizations. Beck, Munich 2016, ISBN 978-3-406-68824-9 , pp. 31–33.

- ↑ M. Metspalu, T. Kivisild, E. Metspalu, J. Parik, G. Hudjashov, K. Kaldma, P. Serk, M. Karmin and others. a .: Most of the extant mtDNA boundaries in south and southwest Asia were likely shaped during the initial settlement of Eurasia by anatomically modern humans. In: BMC Genetics. No. 5, 2004, p. 26 ( doi: 10.1186 / 1471-2156-5-26 ; PMC 516768 (free full text); PMID 15339343 ).

- ↑ Barbara Bramanti, Joachim Burger and others: Genetic Discontinuity Between Local Hunter-Gatherers and Central Europe's First Farmers. In: Science. Volume 326, No. 5949, October 2, 2009, pp. 137–140 (English; ISSN 0036-8075; doi: 10.1126 / science.1176869)

- ↑ Martin Richards et al. a .: Tracing European Founder Lineages in the Near Eastern mtDNA Pool. 2000 ( PDF at stats.gla.ac.uk).

- ↑ Hubert Rehm: No love between farmers and hunters in the Luangwa valley. In: Laborjournal.de. June 16, 2010, changed March 4, 2013, accessed January 12, 2019.

- ↑ Thorwald Ewe: Europe's enigmatic ancestors. In: Image of Science. No. 2, 2011, p. 68: Culture & Society. ( online ( memento of July 15, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) on web.archive.org).

- ↑ Ingo Bading: Die Bandkeramiker - a genetically unique people. In: Studium generale: Articles on evolution, evolutionary anthropology, history and society. November 12, 2010, accessed January 12, 2019.

- ^ Jean Manco: DNA from the European Neolithic. ( Memento of March 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) In: Ancestraljourneys.org. December 22, 2013, accessed on January 12, 2019 (English; Comment: "Page created ... from a larger compendium; last revised 21-01-2016.").

- ↑ Wolfgang Haak: Population genetics of the first farmers in Central Europe. An aDNA study on Neolithic skeletal material. Dissertation, University of Mainz 2006, p. ?? ( PDF ( Memento of October 29, 2013 in the Internet Archive )).

- ↑ Message: Bavaria - Archeology Museum: Face for the «dead of Niederpöring». In: Welt.de. May 22, 2019, accessed June 13, 2019.

- ↑ Barbara Bramanti, Joachim Burger and others: Genetic Discontinuity Between Local Hunter-Gatherers and Central Europe's First Farmers. In: Science. Volume 326, No. 5949, October 2, 2009, pp. 137–140 (English; ISSN 0036-8075; doi: 10.1126 / science.1176869)

-

↑ a b Wolfgang Haak, Peter Forster u. a .: Ancient DNA from the First European Farmers in 7500-Year-Old Neolithic Sites. In: Science. Volume 310, No. 5750, November 11, 2005, pp. 1016-1018 (English; doi: 10.1126 / science.1118725 ; PDF: 212 kB, 3 pages on uni-mainz.de ( Memento from August 28, 2017 on the Internet Archive ) on web.archive.org);

Quotation (?): "(The sample material was taken from more than fifty human skeletons from various locations of the band ceramists in Germany, Austria and Hungary. The locations of the skeletons were linked to settlements of the band ceramists, such as Asparn-Schletz, Eilsleben, Flomborn Halberstadt and Schwetzingen. The sample material intended for the determination was taken from the bones and the tooth pulp according to the standard . In almost 50% of the sample material, the DNA samples of the individuals were in a good condition for further investigations. The mitochondrial DNA was analyzed, which was exclusively about In this study it was found that the N1a DNA branch found by the band ceramists reflected very few similar patterns with the comparative DNA in modern Europeans. Further investigations must verify this fact. It was the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) examined, the int act is only passed on from mother to child (line of reproduction). Everyone - regardless of whether they are men or women - inherits their mtDNA from their mother. " - ↑ DNA Study Reveals Genetic History of Europe. ( Memento from September 13, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Image from sci-news.com from April 24, 2013.

- ↑ The graphic ( Memento from September 13, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) shows the network of 39 prehistoric mitochondrial genomes, divided into two groups: Early Neolithic, left, and Mid-to-Late Neolithic, right . The colored nodes represent the individual (abbreviated) cultures, e.g. B. Bandkeramiker (LBK - Linear Pottery Culture), Paul Brotherton u. a .: Neolithic mitochondrial haplogroup H genomes and the genetic origins of Europeans. In: Nature Communications. 4, article number: 1764; (2013), doi: 10.1038 / ncomms2656 , PMC 3978205 (free full text).

- ↑ Jens Lüning : Some things fit, others don't: State of archaeological knowledge and results of DNA anthropology for the early Neolithic. In: Archaeological Information: Early View DGUF-Tagung. Erlangen 2013, pp. 1–10 ( [3] PDF on dguf.de (Memento from November 7, 2014 in the Internet Archive))

- ^ Iosif Lazaridis, Nick Patterson, Alissa Mittnik, Gabriel Renaud and others. a .: Ancient human genomes suggest three ancestral populations for present-day Europeans. In: Nature. Volume 513, No. 7518, September 18, 2014, pp. 409-413 (English; doi: 10.1038 / nature13673 ).

- ↑ Ruth Berger: How did the Indo-European languages come to Europe? In: Spectrum of Science. Vintage? No. 32, August 2010, pp. 48–57 ( PDF on personal.uni-jena.de).

- ↑ Khaled K. Abu-Amero, José M. Larruga, Vicente M. Cabrera, Ana M. González: Mitochondrial DNA structure in the Arabian Peninsula. In: BMC Evolutionary Biology. No. 8, 2008, p. 45 ( doi: 10.1186 / 1471-2148-8-45 ; PMC 2268671 (free full text); PMID 18269758 ).

- ↑ M. Derenko, B. Malyarchuk, T. Grzybowski, G. Denisova, I. Dambueva, M. Perkova, C. Dorzhu, F. Luzina and others. a .: Phylogeographic Analysis of Mitochondrial DNA in Northern Asian Populations. In: The American Journal of Human Genetics. Volume 81, No. 5, 2007, p. 1025 ( doi: 10.1086 / 522933 ; PMC 2265662 (free full text); PMID 17924343 ).

- ↑ Helmut Horn: The Kinzig. Old and new explanations for the origin of the name Kinzig in the context of the history of settlement in southwest Germany. In: Geschichte-schiltach.de. Extended version 2014 ( PDF: 5.9 MB at geschichte-schiltach.de).

- ^ Paul Brotherton, Wolfgang Haak u. a .: Neolithic mitochondrial haplogroup H genomes and the genetic origins of Europeans. In: Nature.communications. No. 4, April 23, 2013 ( online at nature.com).

- ↑ Martin Richards, Vincent Macaulay, Eileen Hickey, Emilce Vega, Bryan Sykes, Valentina Guida, Chiara Rengo, Daniele Sellitto, Fulvio Kivisild and others. a .: Tracing European Founder Lineages in the Near Eastern mtDNA Pool . In: American Journal of Human Genetics . tape 67 , no. 5 , October 16, 2000, ISSN 0002-9297 , p. 1251-76 , doi : 10.1016 / S0002-9297 (07) 62954-1 , PMID 11032788 , PMC 1288566 (free full text).

- ↑ a b Michael Petraglia, Jeffrey Rose: The Evolution of Human Populations in Arabia: Paleoenvironments, Prehistory and Genetics. Springer, place? 2009, ISBN 978-90-481-2719-1 , pp. 82/83.

- ↑ Malliya Gounder Palanichamy, Cai-Ling Zhang, Bikash Mitra, Boris Malyarchuk, Miroslava Derenko, Tapas Kumar Chaudhuri, Ya-Ping Zhang: Mitochondrial haplogroup N1a phylogeography, with implication to the origin of European farmers. In: BMC Evolutionary Biology. 10, October 12, 2010, p. 304 ( doi : 10.1186 / 1471-2148-10-304 (currently unavailable) ; ISSN 1471-2148 ; PMC 2964711 (free full text); PMID 2093989 ).

- ↑ Wolfgang Haak, Guido Brandt a. a .: Ancient DNA, Strontium isotopes, and osteological analyzes shed light on social and kinship organization of the Later Stone Age. In: Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. Volume 105, USA 2008, pp. 18226-18231.

- ↑ a b Wolfgang Haak, Oleg Balanovsky u. a .: Ancient DNA from European Early Neolithic Farmers Reveals Their Near Eastern Affinities. In: PLoS Biology. Volume 8, No. 11, November 9, 2010, pp. 1–16, online: p. E1000536 (English; doi: 10.1371 / journal.pbio.1000536 ; online at journals.plos.org).

- ↑ a b Guido Brandt, Wolfgang Haak u. a .: Ancient DNA reveals key stages in the formation of central European mitochondrial genetic diversity. In: Science. Volume 342, No. 6155, 2013, pp. 257–261 (English; doi: 10.1126 / science.1241844 ).

- ↑ P. Brotherton et al. a .: Neolithic mitochondrial haplogroup H genomes and the genetic origins of Europeans. In: Nat. Commun. No. 4, 2013, p. 1764.

- ↑ Ornella Semino, Giuseppe Passarino and a .: The Genetic Legacy of Paleolithic Homo sapiens sapiens in Extant Europeans: AY Chromosome Perspective. In: Science. Volume 290, No. 5494, November 10, 2000, pp. 1155–1159 (English; doi: 10.1126 / science.290.5494.1155 ; PDF: 230 kB, 5 pages on citeseerx.ist.psu.edu).

- ↑ Patricia Balaresque, Georgina R. Bowden, Susan M. Adams: A Predominantly Neolithic Origin for European Paternal Lineages. In: PLoS Biology. Volume 8, No. 1, January 19, 2010, p. E1000285 ( doi: 10.1371 / journal.pbio.1000285 ; online at journals.plos.org).

-

↑ State Office for the Preservation of Monuments and Archeology Saxony-Anhalt : Mass execution in the Neolithic Age: Mass grave in Halberstadt testifies to the targeted killing of nine prisoners. In: scinexx.de. June 27, 2018, accessed on March 16, 2020.

Christian Meyer, Corina Knipper u. a .: Early Neolithic executions indicated by clustered cranial trauma in the mass grave of Halberstadt. In: Nature Communications. Volume 9, article number 2472, June 25, 2018 (English; online at nature.com). - ^ Adelheid Bach: The population of Central Europe from the Mesolithic to the Latène period from an anthropological point of view (= annual publication of the Thuringian State Office for Archaeological Monument Preservation. Volume 27). Kommissionsverlag, Konrad Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart 1993, pp. 7–51 ( PDF on zs.thulb.uni-jena.de).

- ↑ Mediterranean skull shape

- ^ Gerhard Heberer, Ilse Schwidetzky, Hubert Walter: Anthropologie. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1970, ISBN 3-436-01167-3 , pp. 224 and 226.

- ^ Kurt Gerhardt: A skull from a ceramic waste pit from Königschaffhausen, Memmingen district. Vol. 6 (1981): Find reports from Baden-Württemberg, pp. 59-64 ( journals.ub.uni-heidelberg.de on journals.ub.uni-heidelberg.de)

- ↑ Kurt Gerhardt: Studies on the anthropology of the Central European Neolithic: I. Skulls and skeletons from graves of the older linear ceramics from Bischleben (district of Gotha). Zeitschrift für Morphologie und Anthropologie, Vol. 45, H. 3 (1953), pp. 338-367

- ^ Wolfram Bernhard: Anthropologie der Bandkeramik. In: Ilse Schwidetzky (Ed.): Anthropologie. Part 2. Fundamenta Series B, Volume 3 The beginnings of the Neolithic from the Orient to Northern Europe. Schwabedissen, Cologne 1978, pp. 128–158.

- ↑ Karl H. Roth-Lutra: January isotherms and anthropological typology among the Europids of the 5th-2nd centuries. Millennium BC Chr. Publishing house? Mainz Jahr ?, pp. 67–79 ( PDF on quartaer.eu).

- ^ Kurt Gerhardt: Human remains from band ceramic graves from Mangolding, Ldkr. Regensburg-Süd; especially a contribution to paleopathology. Publishing company? Riehen b. Basel 1968, pp. 337–347 ( PDF on quartaer.eu).

- ↑ Christina Jacob, Hans-Christoph Strien, Joachim Wahl: Family stories from the Stone Age - Reconstructed family relationships. Excerpt. In: spectrum. P. 12–15 ( Reading sample PDF on Spektrum.de; originally published in Archeology in Germany. Special issue Archeology in the 21st Century: Innovative Methods - Groundbreaking Results. 2010, P. 12–21).

- ↑ Barbara Elisabeth Tiefenböck: The pathological changes in the linear ceramic skeletal remains from Kleinhadersdorf, Lower Austria - an anthropological contribution to the reconstruction of living conditions in the early Neolithic. University of Vienna 2010, p. 165 ( PDF at univie.ac.at).

- ↑ Joachim Wahl, HG König: Anthropological-traumatological examinations of the human skeletal remains from the band ceramic mass grave near Talheim, Heilbronn district (= Find reports from Baden-Württemberg Volume 12). Published by the State Office for Monument Preservation in the Stuttgart Regional Council. Konrad Theiss, Stuttgart December 1987, pp. 65-193.