Ship fresco from Akrotiri

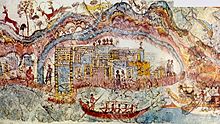

see overall illustration

The ship fresco of Akrotiri is a four-meter-long miniature frieze that was discovered in 1972 during the excavation of the archaeological site of Akrotiri on the Cycladic island of Santorini . The fresco, reconstructed from found fragments, is currently in the depot of the National Archaeological Museum in Athens and is not accessible to the public. The good state of preservation of the fresco, also known as the “ship procession”, is based on the absence of air from the ash rain from the Minoan eruption of the Thera volcano (Santorini) in the 17th or 16th century BC. The excavations took place under the direction of Spyridon Marinatos , who had a fatal accident at the excavation site in 1974.

Archaeological evidence

Coordinates of the place of discovery: 36 ° 21 ′ 6.8 ″ N , 25 ° 24 ′ 11.6 ″ E

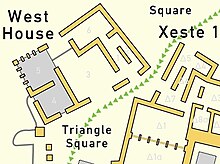

That from around 1650 to 1500 BC The fresco is 3.90 meters long and 0.44 meters high. It was installed above wall niches and a passage in the south-east wall of room 5 in the so-called West House on Dreiecksplatz. The room on the upper floor of the west house, the ceremonial area of the building, had an area of 4 × 4 meters and a height of about 3 meters. The upper wall parts of the room, on which the painted plaster must have been applied, have not been preserved. All the fragments of the frieze that were found had fallen off the wall and were on the floor of the room or, where it had collapsed, in the filling material of the room below, up to three meters below the floor level of room 5. The excavated after its discovery in autumn 1972 The ship's fresco, the fragments of which were brought to Athens for restoration, was part of a surrounding frieze below the ceiling. Like the adjoining room 4 in the southeast, room 5 seems to have had water as a common pictorial program , salt water as well as fresh water.

In addition to the ship procession, various other frescoes have been preserved from room 5. From the window walls, the north-west and south-west walls, there are depictions of two life-size naked youthful adorers below the frieze. Both carry fish and have shaved heads, except for two black curls. The 0.20 meter high frieze on the north-east wall showed a river landscape with various animals and a griffin under the ceiling , and on the 0.40 meter high frieze above the windows of the north-west wall was a coastal settlement with five lancers and a ship's sinking depicted below. In room 5 and the adjoining room 4 in the southeast, which could only be entered from room 5 via the passage under the ship fresco, offering tables , rhyta and other cult vessels were found. This indicates a cult complex , a shrine , which should have an equivalent in the iconography of the frescoes in both rooms.

Room 4 appears to have been a room for the preparation of cult acts, as suggested by a drain and the findings of a bathtub, a bronze kettle, a broken bowl of red dye and a lion's head hyton. From the reveal of the passage leading from room 4 to room 5 comes the fresco of a woman with a lock of snakes on her shaved head and a vessel in her hand that can be identified as a censer. The figure, regarded as a priestess, is made up, she has striking red lips and a red ear, and appears to be walking into room 5. The room with the ship fresco, room 5, was accessed from a larger room in the middle of the house, room 3, with a passage to the stairs. Furthermore, a corridor on the northwest side of the building led from room 5 to a room in which over 100 conical cups and numerous jugs were found. This room 6 was probably a kind of ritual dining room . In the hallway between Room 5 and Room 6, a brick cupboard contained other vessels, including saucepans and rhyta.

Because of the three entrances, the large window areas on two walls and recessed niches and cupboards in the walls, room 5 with the ship fresco had little space for wall paintings. The fact that there was still this diversity of the picture program speaks for the cultic significance of the frescoes. For decorative purposes, they were not required on the richly articulated walls of the room. The murals were oriented to the west, in the corner between the two window walls. There a three-legged sacrificial table was found on a window sill, which was colorfully decorated with swimming dolphins and various sea motifs. Both young adorants on the window walls were shown walking towards the west corner. The procession of ships on the frieze also apparently moved in that direction.

- Frescoes from room 5 of the west house

Description of the fresco

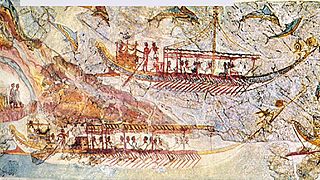

The ship fresco by Akrotiri from the south-east wall of room 5 on the upper floor of the west house shows a procession of ships, some of which are decorated and decorated with flowers. A total of 14 ships or boats are shown on the fresco, including 7 larger ships, one of them with a square sail , the others with around 20 people with paddles on the sides facing the viewer. From this point of view, all ships involved in the procession have a rudder on the left side, at the stern , attached to the outside of the ship's wall , so that it can be seen that they are moving from left to right in the picture. The big ships have also created behind a wooden rods clad with cattle hides downwardly and upwardly open cabin , a cabin for the skipper ( ancient Greek Nauarchos ), and with the exception of the sailing ship canopy-like structures in the shipping center. In addition to the sailing ship, two of the procession ships have masts in the middle , from the tips of which ropes are attached towards the bow and stern. On one of the two ships, the ropes are hung with objects, perhaps to decorate and identify the most important ship in the fleet. The ship's side is painted with lions and dolphins , the sailing ship with pigeons .

The processional ships move from one land mass to another on the fresco, which could be land, islands, or both. Between these ships, dolphins jump out of the water, a total of at least 15 animals, some right next to each other. Buildings can be seen on both land masses, some of which are intended to safely represent settlements or cities. The city on the left, northeast side of the frieze is smaller than the one on the right, southwest side. The starting point of the ship procession is on the left. The houses in the city there are made of gray, white, red and yellow stone blocks. The city is apparently surrounded by a ring of water, with a boat with 5 (10?) Rowers, a helmsman and a skipper in the foreground . The latter sits open, without a cabin, in the stern of the boat. Since it is much smaller than the procession ships, it is impossible to tell whether it wants to join the procession even though it is heading in the same direction. To the left of the “water ring”, further buildings can be seen on the land mass that are not as close together as in the city. Behind the “water ring” a lion is chasing three deer in a tree-lined landscape that is dominated by two mountain peaks.

The destination of the ship procession on the right side of the fresco is a larger city with a flight of stairs in the middle, as they are known in the Minoan culture from Knossos or Phaistos . The multi-storey buildings are made of gray, red, and yellow stone blocks. On the gray masonry on the right side there are at least four cult horns and on the left side of the city at least two cult horns, a sign of religious authority and a reference to a sacred building of the Minoan religion . To the left of the city is a bay with two ships lying in it. This is followed by a second, smaller harbor bay in which there are three boats. A small boat without superstructures with only two people travels between the two ports, which apparently does not belong to the ship's procession. A multi-storey red building has been erected behind the bank of the small harbor with the three boats. Behind this, on a mountain, there is another building made of white and yellow masonry.

- Ship procession in the middle part of the fresco

The people on the fresco are shown in stylized form. They differ in their clothing and their activities. The people of the city on the left wear tunic-like robes. With the exception of two people dressed in animal skins on either side of the “water ring” to the left of the city, the residents watch the ship procession from the beach or the roofs of their houses. The rowers on the ship in front, like all the helmsmen on the fresco, wear a Minoan apron with a bare chest . The same applies to the people in front of the city on the right-hand side, one of whom is leading a sacrificial animal, and some runners and a fisherman on the land mass there. The passengers of the procession ships are dressed in tunics or long capes. They are shown seated opposite one another with or against the direction of travel. Four rural dwellers in animal skins stand on the large harbor bay in front of the town on the right. People of both sexes are shown in the city. In contrast to all other parts of the fresco, women can also be recognized by their hairstyles and white skin. On a balcony with cult horns on the left side of the city stands a woman interpreted as a priestess with a raised right arm, directly behind her a naked child. Like them, all other people in the city, dressed in tunics or cloaks, look in the direction of the arriving ships.

Interpretation of the fresco

Hypotheses

detail of the ship fresco of the starting point of the procession

The various interpretations of the ship fresco from Akrotiri deal on the one hand with the localization of the ship procession and on the other hand with the possible content of the scenery, i.e. what is represented in the picture. Since the fresco was found in an archaeological site on Santorini, a reference to the island can be assumed. This has been included in all previous attempts at interpretation. The geological formations to be recognized on the two land masses, such as coastlines and mountains, and the depicted natural conditions, the flora and fauna, play a major role. When interpreting the ship procession, the find situation and the context of the find must be taken into account. In addition, the representation of the people, the ships and the buildings gives clues for assessing what is happening. Among the descriptions of the ship fresco there were interpretations as an expedition to Libya , a military expedition with the participation of Mycenaeans , a religious celebration or, in connection with the opposite frieze from room 5 of the west house, a shipwreck as a sign of the dangers of the sea.

The excavation director from Akrotiri until 1974, Spyridon Marinatos, thought the scenery was a return trip from an expedition to Libya. He had occupied himself with the construction of the ships shown and realized that they were not driven by rowing but by paddling. "The striking short-acting belts are of the Rojern maneuvered [rowers] with both hands. The Rojers lean their chests sharply over the gunwale so that their backs form a wavy line. ”As an example, he refers to the drawing of the best-preserved ship in the fresco with its 21“ Rojers ”on the starboard side . Marinatos' conclusion was: "For maneuvering the Rojer with the strikingly short oars in the otherwise unoccupied position I can only give one explanation: the water is too shallow, and the Rojer p a d d e l n ." In the following, he connects waters with the Great Syrte off Libya. Also on the remaining parts of the opposite frieze, on the north-west wall in room 5 of the west house, he believes he can recognize Libyans from the way of depiction of the drowned shipwreck.

Apart from this localization attempt, Spyridon Marinatos dealt with the construction of the ships on the fresco. Based on information from Vitruvius , he assumes that the best preserved ship, which is 62 centimeters long on the fresco, has an original length of 33.75 meters and a maximum width in the middle of over 2 meters. The ship was propelled by 42 "Rojern". In addition to the men with the coats in the middle of the ship, Marinatos recognizes a skipper in the stern cabin made of rods, a small figure sitting in front of it, perhaps a cabin boy , a helmsman or helmsman and one of the "rojers" with an instrument, possibly an elongated rattle, person setting the pace. For the ship size, he also refers to the comparison of the stern cabin ( called bezeichnetρια ikria by Homer ) with the representation of eight such cabins in original size of over 1.40 meters in height on the frescoes in room 4 of the upper floor of the west house. The first large ship of the procession on the left side of the ship fresco is 75 centimeters longer than the one described, but due to the perspective from the position in the foreground, it is not necessarily larger than the one behind. Marinatos characterized the large processional ships as Amphielissa ( Greek ἀμφιέλισσα ).

Recent studies reduce the original dimensions of the ships shown by Spyridon Marinatos somewhat. The best preserved ship could have had a length of 23.2 meters and a width of 4.7 meters. The smaller ship in front of the left town would then have the dimensions 9.7 × 2.0 meters, the main ship 23.6 × 4.7 meters and the sailing ship 16.7 × 3.3 meters.

For the archaeologist Nanno Marinatos , daughter of Spyridon Marinatos, the motifs of the ship's decorations point to a religious occasion of the ship's procession. She recognizes in it a “festival lift at sea”, a celebration in which “the fleet plays an important role”. The finds from rooms 4 and 5 of the upper floor of the west house, such as sacrificial tables, rhyta and other cult vessels, as well as the contents of the other frescoes discovered there, depictions of a priestess, two adorers or a griffin in the river landscape, put the ship fresco in one cultic frame. From the movement of the ships through the "exhausting, archaic method" of paddling, like in a dragon boat , instead of rowing, Nanno Marinatos recognizes a ritual excursion. She also refers to the female person with her arm raised on the balcony with the cult horns in the right town, in her eyes a priestess, and to the “youth procession” in front of the town where an animal is sacrificed.

Nanno Marinatos is not committed to localization. However, she assumes that the town on the right side of the ship procession is likely Akrotiri, where the fresco was found. She cites Peter M. Warren when she states that “the topographical information in the fresco fits perfectly to the Aegean Sea ”, which also applies to the reproduction of flora and fauna. In this context, she considers a return trip from an expedition to Libya to be unlikely. Against this would also argue that “the movement of the ships by paddling cannot be reconciled with a long sea voyage”. Marinatos further refers to the differences between the cities depicted, the one on the left consisting of simple buildings, the one on the right with “impressive structures” and cult horns on the top of the wall to the right of the city gate. Since she considers the city on the right to be Akrotiri, Nanno Marinatos assumes that the city on the left is a "dependent settlement 'in the province' on Thera or a neighboring island". What seems unusual to her, however, is the “free roaming lion” in the local landscape, hunting three deer.

The archaeologist Thomas F. Strasser sees no reason to believe that the city of the arrival of the ship procession is on the right side of the Akrotiri fresco. He justified this with the fact that the representation of a large port or even two ports did not fit Akrotiri, after all the excavation site was on the south coast of Santorini, on the outside of the island, and the caldera , the "best natural one, stretched just one kilometer further north Port in the Aegean, if not the entire Mediterranean ”. Strasser assumes a crescent-shaped land mass for Thera before the Minoan eruption, with a northwest and western land connection via Thirassia to Aspronisi and an island within the caldera.

Strasser, on the other hand, agrees with the interpretation of the frieze as a nautical festival or religious ceremony as well as a combination of both. Like Nanno Marinatos, he derives this from the decoration of the ships, the festive clothing of the passengers and the practice of paddling, which does not speak for a long and far journey. Strasser interprets the depicted dolphins as a metaphor for the open sea, he considers the animal world of the land masses to be Cycladic, including the lion, referring to bone finds from Agia Irini on Kea and the frequent use of lions as a motif in Aegean art. For lions, as well as monkeys, he accepts an import from Africa. Finally, he formulates his thesis that the fresco depicts a procession within the caldera with a view of the open sea from the east. The starting point was near Raos, near Kapparies, on the Akrotiri peninsula, the destination between Aspronisi and Cape Tripiti on Thirassia .

The geologists Walter L. Friedrich and Annette Højen Sørensen also interpret the procession inside the caldera, but move it in the opposite direction. On the basis of geological conditions and archaeological research, they prefer the bay of Mouzaki in northern Santorini as the starting point and the archaeological sites at Balos and Raos near Akrotiri as the arrival point for the fleet.

Controversy

The excavations at Akrotiri on Santorini produced the richest collection of wall paintings from the Bronze Age in the Aegean. Of the representations, there was probably no more subject of scientific research than the fresco of the so-called ship procession. The views on content and localization are correspondingly controversial.

Even the first interpretation of the excavation leader, Spyridon Marinatos, that the fresco depicts the return journey of a fleet from Libya to Akrotiri, was mostly contradicted. His daughter Nanno Marinatos gave the most important reasons for this: The depicted mode of paddling was unsuitable for a trip from the coast of Africa to the Aegean Sea and the view that the ship fresco was a continuation of the northwest frieze on which her father believed to see shipwrecked Libyans , was not justified, even if both paintings were in a certain context. According to Thomas Strasser, the lion chasing the three deer in the landscape on the left side of the ship fresco is not an animal that does not fit into the Aegean Sea, but is a common feature in art. Only the Lion of Kea , the Lion Gate of Mycenae or the Lion Terrace on Delos are referred to here. Even in the Temenos of Artemidoros at the northern end of Ancient Thera there is a lion carved out of the stone.

The thesis that the city depicted on the right-hand side of the ship's fresco is Akrotiri has often been adopted, for example by Geraldine Gesell (1980), Ellen Davis (1983), Nanno Marinatos (1984), Joseph Shaw (1990) , Christos Doumas (1992), Ora Negbi (1994), Stuart Manning et al. (1994), Marjatta Luton (2000), Christina Televantou (2000) and Philip Betancour (2007). Thomas Strasser replies that there is no reasonable reason to assume that the city of arrival of the ship procession is Akrotiri and not some other Bronze Age urban settlement. Five cities are shown in room 5 of the west house. Strasser thinks it would be a "strange and dogmatic convergence of scientific opinion that only one of them should be considered an akrotiri". Strasser countered Christos Doumas' attempt in 2007 to connect the "double port" on the right side of the fresco with Akrotiri that such a reconstruction of the port facilities at the excavation site would be problematic because the sea level was lower at the time of the Minoan eruption. In addition, there were many settlements with double ports in the eastern Mediterranean during the Bronze Age, 17 of which are known from excavations. And the ports in particular speak against the fact that the town on the right-hand side of the fresco is Akrotiri, as the caldera in the north was a much better natural port.

The view of the city on the right side of the ship's fresco does not match the excavation results of Akrotiri either. Cult horns of the size shown on walls or a flight of steps are known from Knossos, but not from excavations on Santorini. In Akrotiri, only smaller cult horns were found as an architectural element on a house, after which the open space in front of the house was called “Place of the Double Horns”. Strasser avoids this in his theory by locating the right town in an area that no longer exists today, on a former land mass between Thirassia and Aspronisi, southeast of the Alafouzos quarry of Thirassia. For him, even the city on the left lies within the caldera, near Raos in the south of Santorini. He describes the west house of Akrotiri as modestly furnished, with all the amenities for its residents, but in no way "royal" or aimed at external impact. As the larger house of the Akrotiri settlement, the west house dominates the triangle square. However, it fits into the settlement structure, a settlement that in no way resembles the palace complexes on Crete or the representations of the cities on the ship fresco.

Nanno Marinatos considers the west house to be the residence of a priestly family. In contrast to the adorants with the fishes in room 5 on the upper floor, the 'young priestess' in the passage from room 4 to room 5, painted "carelessly", speaks against this. Captain's cabins ”or Ikrias in room 4, one could rather speak of an“ admiral's house ”, as is the case occasionally, where skippers met to sit together in room 3 on the upper floor, in room 6 to eat or to be entertained from it and to perform ritual sacrifices in the western corner of room 5. The cultic purpose of room 5 is hardly doubted today. However, there are still differences regarding the content of the frescoes. Some scientists, like Konstantinos Iliakis (1978), Sarah Morris (1989, 2000), Stefan Hiller (1990), Tessy Sali (2000), Christos Boulotis (2005), Eric H. Cline and Assaf Yasur-Landau (2007) and Vance Watrous (2007) assume that no real landscapes or special occasions are depicted, but traditions or mythological stories. However, since there are no scriptures from the Minoan culture whose contents are known, neither the Cretan hieroglyphs nor the linear script A have been deciphered, allegories have a poor basis. The content of the frescoes can only be deduced from the iconography.

This leads to the symbolism of the frescoes in room 5 of the west or admiral house. Like the ship fresco, the other miniature friezes are also very detailed. The naturalistic representation is noticeable, but deviates from this in two points, with the depicted big cats in the wild and with the grasping on the northeast frieze with the river landscape. While lions and leopards were often used in Aegean art, they are not part of the natural habitat. Griffins are only to be understood in a mythological or cultic context. In room 3 of the upper floor of Xesti 3 of the Akrotiri archaeological site, a fresco was found that shows a goddess sitting on a throne, behind which there is a griffin. It is also known as the fresco of the "crocus pickers" or "saffron collectors", as several women can be seen collecting the flowers of the Crocus sativus in baskets and offering them to the goddess. A blue monkey stands directly in front of the goddess.

Nanno Marinatos describes the enthroned goddess in Xesti 3 as the "mistress of nature", as fertility and mother goddess. It is often associated with the Potnia theron , translated as "mistress of the wild", interpreted as "mistress of the wild animals". It was usually depicted symmetrically between two wild animals such as lions, griffins, deer or water birds. Corresponding frescoes and seals are known from the Minoan period. Her attributes were later passed on to the goddess Artemis , who was nicknamed Pothnia theron by Homer ( Iliad 21,470). In Mycenaean times , the name qe-ra-si-ja ( ) or a-ti-mi-te ( ???? ) appears on linear B tables from Knossos as a nickname for Artemis, Mycenaean a-te-mi-to ( ???? ) or a-ti-mi-te ( ???? ) ???? ), which probably means "goddess of Thera". In Greek mythology , the titan Rhea appears in the company of lions. The griffin and the big cats in the river landscape and the lion in the ship fresco could be understood as symbols for the goddess and her relationship to the island of Thera. They symbolized the presence of the goddess in relation to a certain area of the respective image, in the fresco of the river landscape for the entire frieze, in the ship fresco for the land mass behind the left city. In both cases one could assume a connection between the goddess, Potnia theron , and the island of Thera (Santorin).

If you now look at the relationship between the frescoes from room 5 of the west house, you can also see a certain orientation towards the west or south-west. According to Nanno Marinatos, this applies to both the adorants with the fish, who, shown walking, meet each other while moving in the western corner of the room, as well as the friezes under the ceiling on the north-west and south-east wall, both iconographically facing south-west point. The ship fresco is not a continuation of the north-west frieze, as mentioned by some scholars, but is to be understood in a thematic context of victory and victory celebration. The north-east frieze with the griffin and the hunting scenes in the river landscape form the starting point for both. The north-east frieze could be understood as Thera's landscape, in which Potnia theron, symbolized as a griffin, is at home, and the window side of the room, in the western corner of which sacrifices were made, as the opening of the caldera to the open sea, through which the fleet of Thera's inhabitants to others Islands and countries. The orientation and content of the frescoes in room 5 as well as the sacrificial table found there with the painted dolphins and sea motifs speak for the cult place of a sea deity .

The hypotheses that locate the ship procession within the caldera do not take up the orientation of the fresco to the southwest. With Thomas Strasser the destination is in the northwest, with Walter Friedrich and Annette Højen Sørensen in the south. The dolphins as a metaphor for the open sea, as assumed by Strasser, are not taken into account by Friedrich and Højen Sørensen. The same applies to the non-existent land mass between the left and right cities on the ship fresco, since both believe that the procession should lead along the coast within the caldera. Strasser's view, however, that the connection between the caldera and the open sea is depicted, appears questionable because of the dolphins jumping out of the water between the ships. If his interpretation of the dolphins is correct, at least the rear ships shown above lead in the open sea to get from one place within the caldera to another place within the caldera. The metaphor of the dolphins rather supports Nanno Marinatos' view that the ship procession connects one island with another, even if Marinatos assumes that the ships could come from "a neighboring island" to Akrotiri, but do not have such a destination.

The hunting scene as a symbol of the presence of the goddess (Potnia theron) on Thera behind the city on the left side of the fresco speaks for a different direction: from the caldera of Santorini to the west and south over the sea to a neighboring island. Comparisons with modern long boats of the Maori , Haida and Nootkan from Vancouver Island driven by paddling suggest a cruising speed of about 7 knots or 13 km / h and a range of 800 to 2200 kilometers for the Cycladic ships on the ship fresco of Akrotiri. Crete, the closest island in the southwest with the center of the Minoan culture Knossos, would have been reachable in this way in about ten hours at a distance of about 130 kilometers, with the support of the Meltemi and the associated ocean currents. For ships like the boat with the square sail on the fresco, there were and probably were good sailing connections from the island of Thera to the north coast of Crete almost all year round in ancient times.

literature

- Spyridon Marinatos : The ship fresco from Akrotiri, Thera . In: Dorothea Gray, Friedrich Matz , Hans-Günter Buchholz (eds.): Archaeologia Homerica . tape I . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1974, ISBN 3-525-25406-7 , Chapter G: Seewesen , pp. 141 .

- Peter M. Warren: The Miniature Fresco from the West House at Akrotiri, Thera, and Its Aegean Setting . In: The Journal of Hellenic Studies . tape 99 . Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies, London 1979, p. 115-129 , JSTOR : 630636 .

- Avner Raban: The Thera Ships: Another Interpretation . In: American Journal of Archeology . No. 88.1 . Archaeological Institute of America, January 1984, pp. 11-19 , JSTOR : 504594 .

- Sarah P. Morris: A Tale of Two Cities: The Miniature Frescoes from Thera and the Origins of Greek Poetry . In: American Journal of Archeology . No. 93.4 . Archaeological Institute of America, October 1989, pp. 511-535 ( digital version [PDF; 8.8 MB ; accessed on November 12, 2015]).

- Thomas F. Strasser: Location and Perspective in the Theran Flotilla Fresco . In: Journal of Mediterranean Archeology . No. 23.1 . Equinox Publishing, 2010, ISSN 0952-7648 ( digitized [PDF; 2.1 MB ; accessed on November 14, 2015]).

- Thomas F. Strasser, Anne P. Chapin: Geological Formations in the Flotilla Fresco from Akrotiri . In: Gilles Touchais, Robert Laffineur, Françoise Rougemont (eds.): Aegaeum 37 . Peeters, Löwen / Lüttich 2014, p. 57–66 ( digitized version [accessed November 14, 2015]).

- Walter L. Friedrich, Annette Højen Sørensen, Samson Katsipis: Santorini Before the Minoan Eruption: The Ship Fresco from Akrotiri - A Geological and Archaeological Approach . In: Gilles Touchais, Robert Laffineur, Françoise Rougemont (eds.): Physis. 14ème rencontre égéenne international, Paris, dec. 2012 (Aegaeum 37) . Peeters, Löwen / Lüttich 2014, p. 475–479 ( digitized [accessed November 22, 2015]).

Individual evidence

- ↑ Hans-Joachim Löwer: The super volcano . In: National Geographic . Edition June 2014. Gruner + Jahr, Hamburg 2014, p. 48 ( digitized version [accessed on November 14, 2015]).

- ↑ Hans-Joachim Löwer: The super volcano . In: National Geographic . Edition June 2014. Gruner + Jahr, Hamburg 2014, p. 38–39 ( digitized version [accessed November 14, 2015]).

- ↑ Annette Højen Sørensen, Walter Ludwig Friedrich, Samson Katsipis, Kirsten Molly Søholm: Miniatures of meaning - interdisciplinary approaches to the miniature frescoes from the west house at Akrotiri on Thera . In: Conferences of the State Museum for Prehistory Halle . tape 9 , 2013, p. 151 ( digital copy [PDF; 1,2 MB ; accessed on November 14, 2015]).

- ^ Thomas F. Strasser: Location and Perspective in the Theran Flotilla Fresco . In: Journal of Mediterranean Archeology . No. 23.1 . Equinox Publishing, 2010, pp. 4 ( digital version [PDF; 2.1 MB ; accessed on November 14, 2015]).

- ^ A b Peter M. Warren: The Miniature Fresco from the West House at Akrotiri, Thera, and Its Aegean Setting . In: The Journal of Hellenic Studies . tape 99 . Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies, London 1979, p. 115-129 , JSTOR : 630636 .

- ^ Lionel Casson : Bronze Age Ships. The evidence of the Thera wall paintings . In: The International Journal of Nautical Archeology and Underwater Exploration . No. 4.1 , 1975, p. 3-10 , doi : 10.1111 / j.1095-9270.1975.tb00898.x .

- ↑ Spyridon Marinatos : The ship fresco from Akrotiri, Thera . Ed .: Dorothea Gray, Friedrich Matz, Hans-Günter Buchholz. Volume I, Chapter G: Marine Life. , S. 141 .

- ↑ Annette Højen Sørensen, Walter Ludwig Friedrich, Samson Katsipis, Kirsten Molly Søholm: Miniatures of meaning - interdisciplinary approaches to the miniature frescoes from the west house at Akrotiri on Thera . In: Conferences of the State Museum for Prehistory Halle . tape 9 , 2013, p. 152 ( digital version [PDF; 1,2 MB ; accessed on November 14, 2015]).

- ↑ Annette Højen Sørensen, Walter Ludwig Friedrich, Samson Katsipis, Kirsten Molly Søholm: Miniatures of meaning - interdisciplinary approaches to the miniature frescoes from the west house at Akrotiri on Thera . In: Conferences of the State Museum for Prehistory Halle . tape 9 , 2013, p. 149 ( digital version [PDF; 1,2 MB ; accessed on November 14, 2015]).

- ↑ Jeremy B. Rutter, JoAnn Gonzalez-Major: Akrotiri on Thera, the Santorini Volcano and the Middle and Late Cycladic Periods in the Central Aegean Islands. The Frescoes from Akrotiri. Aegean Prehistoric Archeology, accessed November 14, 2015 .

- ↑ a b c d Nanno Marinatos: Art and religion in ancient Thera . For the reconstruction of a Bronze Age society. Mathioulakis, Athens 1987, ISBN 960-7310-26-8 , image programs : Das ‚Westhaus', p. 34-35 .

- ^ Nanno Marinatos: Art and Religion in ancient Thera . For the reconstruction of a Bronze Age society. Mathioulakis, Athens 1987, ISBN 960-7310-26-8 , image programs : Das ‚Westhaus', p. 48 .

- ^ Nanno Marinatos: Art and Religion in ancient Thera . For the reconstruction of a Bronze Age society. Mathioulakis, Athens 1987, ISBN 960-7310-26-8 , image programs : Das ‚Westhaus', p. 44-46 .

- ^ Nanno Marinatos: Art and Religion in ancient Thera . For the reconstruction of a Bronze Age society. Mathioulakis, Athens 1987, ISBN 960-7310-26-8 , image programs : Das ‚Westhaus', p. 38 .

- ^ Thomas F. Strasser: Location and Perspective in the Theran Flotilla Fresco . In: Journal of Mediterranean Archeology . No. 23.1 . Equinox Publishing, 2010, ISSN 0952-7648 ( abstract [accessed November 14, 2015]).

- ↑ a b Spyridon Marinatos: The ship fresco from Akrotiri, Thera . Ed .: Dorothea Gray, Friedrich Matz, Hans-Günter Buchholz. Volume I, Chapter G: Marine Life. , S. 148 .

- ↑ Thomas Guttandin, Diamantis Panagiotopoulos, Hermann Pflug, Gerhard Plath: Islands of the winds. The maritime culture of the Bronze Age Aegean . Exhibition catalog. Institute for Classical Archeology of the Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg, Heidelberg 2011, ISBN 978-3-00-035216-4 , Late Bronze Age shipbuilding, p. 107–108 ( digitized version [accessed November 29, 2015]).

- ↑ Michael Siebert: Cult and divinity in the wall paintings of Akrotiri. (PDF; 12.1 MB) On the interpretation of the double horns. homersheimat.de, 2014, p. 13 , accessed on December 20, 2015 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g Nanno Marinatos: Art and religion in ancient Thera . For the reconstruction of a Bronze Age society. Mathioulakis, Athens 1987, ISBN 960-7310-26-8 , image programs : Das ‚Westhaus', p. 41 .

- ^ Nanno Marinatos: Art and Religion in ancient Thera . For the reconstruction of a Bronze Age society. Mathioulakis, Athens 1987, ISBN 960-7310-26-8 , image programs : Das ‚Westhaus', p. 42 .

- ↑ a b Nanno Marinatos: Art and Religion in ancient Thera . For the reconstruction of a Bronze Age society. Mathioulakis, Athens 1987, ISBN 960-7310-26-8 , Public festivals on the frescoes of Thera, p. 53 .

- ↑ a b Spyridon Marinatos: The ship fresco from Akrotiri, Thera . Ed .: Dorothea Gray, Friedrich Matz, Hans-Günter Buchholz. tape I , Chapter G: Marine , p. 150-151 .

- ↑ Spyridon Marinatos: The ship fresco from Akrotiri, Thera . Ed .: Dorothea Gray, Friedrich Matz, Hans-Günter Buchholz. tape I , Chapter G: Marine , p. 143 .

- ^ Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott: An Intermediate Greek-English Lexicon . Clarendon Press, Oxford 1889, ἀμφιέλισσα ( digitized [accessed November 18, 2015]).

- ↑ Thomas Guttandin, Diamantis Panagiotopoulos, Hermann Pflug, Gerhard Plath: Islands of the winds. The maritime culture of the Bronze Age Aegean . Exhibition catalog. Institute for Classical Archeology of the Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg, Heidelberg 2011, ISBN 978-3-00-035216-4 , The ship frieze in the west house of Akrotiri, p. 66 ( digitized version [accessed November 29, 2015]).

- ↑ a b c d Thomas F. Strasser: Location and Perspective in the Theran Flotilla Fresco . In: Journal of Mediterranean Archeology . No. 23.1 . Equinox Publishing, 2010, ISSN 0952-7648 , p. 6–8 ( digitized [PDF; 2.1 MB ; accessed on November 14, 2015]).

- ^ A b Thomas F. Strasser: Location and Perspective in the Theran Flotilla Fresco . In: Journal of Mediterranean Archeology . No. 23.1 . Equinox Publishing, 2010, ISSN 0952-7648 , p. 9 ( digital version [PDF; 2.1 MB ; accessed on November 14, 2015]).

- ^ A b Thomas F. Strasser: Location and Perspective in the Theran Flotilla Fresco . In: Journal of Mediterranean Archeology . No. 23.1 . Equinox Publishing, 2010, ISSN 0952-7648 , p. 11 ( digital version [PDF; 2.1 MB ; accessed on November 14, 2015]).

- ^ A b c Thomas F. Strasser: Location and Perspective in the Theran Flotilla Fresco . In: Journal of Mediterranean Archeology . No. 23.1 . Equinox Publishing, 2010, ISSN 0952-7648 , p. 16 ( digital version [PDF; 2.1 MB ; accessed on November 14, 2015]).

- ^ Walter Ludwig Friedrich, Annette Højen Sørensen: New light on the Ship Fresco from Late Bronze Age Thera . In: Praehistorische Zeitschrift . tape 85 , issue 2. De Gruyter, January 2011, ISSN 0079-4848 , p. 243-257 ( academia.edu [accessed November 18, 2015]).

- ^ Thomas F. Strasser: Location and Perspective in the Theran Flotilla Fresco . In: Journal of Mediterranean Archeology . No. 23.1 . Equinox Publishing, 2010, ISSN 0952-7648 , p. 3 ( digital version [PDF; 2.1 MB ; accessed on November 14, 2015]).

- ^ Nanno Marinatos: Art and Religion in ancient Thera. For the reconstruction of a Bronze Age society . Mathioulakis, Athens 1987, ISBN 960-7310-26-8 , image programs : Das ‚Westhaus', p. 40 .

- ↑ Michael Siebert: Cult and divinity in the wall paintings of Akrotiri. (PDF; 12.1 MB) On the interpretation of the double horns. homersheimat.de, 2014, pp. 12-14 , accessed December 20, 2015 .

- ^ Thomas F. Strasser: Location and Perspective in the Theran Flotilla Fresco . In: Journal of Mediterranean Archeology . No. 23.1 . Equinox Publishing, 2010, ISSN 0952-7648 , p. 20 ( digital copy [PDF; 2.1 MB ; accessed on November 14, 2015]).

- ^ Thomas F. Strasser: Location and Perspective in the Theran Flotilla Fresco . In: Journal of Mediterranean Archeology . No. 23.1 . Equinox Publishing, 2010, ISSN 0952-7648 , p. 5 ( digital version [PDF; 2.1 MB ; accessed on November 14, 2015]).

- ^ Nanno Marinatos: Art and Religion in ancient Thera . For the reconstruction of a Bronze Age society. Mathioulakis, Athens 1987, ISBN 960-7310-26-8 , image programs : Das ‚Westhaus', p. 51 .

- ^ Nanno Marinatos: Art and Religion in ancient Thera. For the reconstruction of a Bronze Age society . Mathioulakis, Athens 1987, ISBN 960-7310-26-8 , Public festivals on the frescoes of Thera, p. 61 .

- ^ Nanno Marinatos: Art and Religion in ancient Thera . For the reconstruction of a Bronze Age society. Mathioulakis, Athens 1987, ISBN 960-7310-26-8 , Public festivals on the frescoes of Thera, p. 68 .

- ↑ Kristin Schuhmann: Beauty and the Beasts . The mistress of the animals in Bronze Age and Early Iron Age Greece. Master thesis. Ruprecht-Karls-Universität, Heidelberg March 2009, p. 10 ( online [PDF; 2.7 MB ; accessed on November 20, 2015]).

- ↑ Kristin Schuhmann: Beauty and the Beasts . The mistress of the animals in Bronze Age and Early Iron Age Greece. Master thesis. Ruprecht-Karls-Universität, Heidelberg March 2009, p. 15 ( online [PDF; 2.7 MB ; accessed on November 20, 2015]).

- ^ The New Pauly (DNP) . tape 10 . Metzler, Stuttgart 2001, Potnia theron, p. 236 .

- ↑ Fritz Blakolmer: From the Throne Room at Knossos the Lion Gate of Mycenae: continuities in Picture Arts and Palace ideology . In: Fritz Blakolmer, Claus Reinholdt, Jörg Weilhartner, Georg Nightingale (eds.): Austrian research on the Aegean Bronze Age 2009 . Files from the conference from March 6th to 7th, 2009 at the Department of Classical Studies at the University of Salzburg. Phoibos, Vienna 2011, ISBN 978-3-85161-047-5 , image appendix from p. 75, p. 63–80 ( digitized version [accessed November 20, 2015]).

- ↑ ΙΛΙΑΔΟΣ - μάχη παραποτάμιος (ancient Greek original of the 21st song of the Iliad). gottwein.de, accessed on November 25, 2015 .

- ↑ qe-ra-si-yes. minoan.deaditerranean.com, accessed November 21, 2015 .

- ↑ qe-ra-si-yes. Palaeolexicon, accessed November 25, 2015 .

- ^ Nanno Marinatos: Art and Religion in ancient Thera . For the reconstruction of a Bronze Age society. Mathioulakis, Athens 1987, ISBN 960-7310-26-8 , image programs : Das ‚Westhaus', p. 44 .

- ↑ Thomas Guttandin, Diamantis Panagiotopoulos, Hermann Pflug, Gerhard Plath: Islands of the winds. The maritime culture of the Bronze Age Aegean . Exhibition catalog. Institute for Classical Archeology of the Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg, Heidelberg 2011, ISBN 978-3-00-035216-4 , Cycladic ships on the way, p. 86 ( digitized version [accessed December 4, 2015]).

- ↑ Peter O. Walter: Winds in the Mediterranean: The Meltemi. European Sailing Information System, 1996, accessed October 7, 2016 .

- ^ Arne Korf: Wind, Weather and Navigation on the Greek Seas. Sun Yachting Germany, accessed October 7, 2016 .

- ↑ Distance from Santorini to Heraklion. In: luftlinie.org. Retrieved December 6, 2015 .

- ↑ Thomas Guttandin, Diamantis Panagiotopoulos, Gerhard Plath: On the way with the Minoans. Sea routes and propulsion technologies. In: Scinexx . October 12, 2011, accessed October 17, 2016 .

- ↑ Thomas Guttandin, Diamantis Panagiotopoulos, Gerhard Plath: The islands of the winds. Heidelberg University, October 4, 2010, accessed October 19, 2016 .

- ↑ Thomas Guttandin, Diamantis Panagiotopoulos, Hermann Pflug, Gerhard Plath: Islands of the winds. The maritime culture of the Bronze Age Aegean . Exhibition catalog. Institute for Classical Archeology at the Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg, Heidelberg 2011, ISBN 978-3-00-035216-4 , Geographical Requirements, p. 14 ( digitized version [accessed October 19, 2016]).

Web links

- Thomas Guttandin, Diamantis Panagiotopoulos, Gerhard Plath: The islands of the winds. Heidelberg University, October 4, 2010, accessed October 7, 2016 .

- Andrea Salimbeti: The Greek Age of Bronze: Ships. In: salimbeti.com. October 28, 2015, accessed November 14, 2015 .