Republic of Serbian Krajina

| Република Српска Крајина | |||||

|

Republika Srpska Krajina |

|||||

| Republic of Serbian Krajina | |||||

|

|||||

| Motto : Samo sloga Srbina spasava | |||||

| Official language | Serbian | ||||

| Capital | Knin | ||||

| founding | 1991 | ||||

| resolution | 1995 | ||||

| National anthem |

Bože Pravde Sokolovi, sivi tići |

||||

The Republic of Serbian Krajina ( Serbian Република Српска Крајина Republika Srpska Krajina ), РСК / RSK for short, was an internationally unrecognized de facto regime that controlled around a third of Croatian territory during the Croatian War from 1991 to 1995 . Its name refers to Vojna krajina , the Serbian and Croatian name of the Austrian military border .

On December 19, 1991, part of the area was initially proclaimed an independent state with the intention of later annexing it to the Republika Srpska and Serbia .

Knin was declared the capital of the RSK . In addition, a separate currency was created, the dinar of the Republic of Serbian Krajina (Serbian Dinar Republike Srpske Krajine ). In 1992 the Serbian-controlled areas in eastern Slavonia and Baranja joined the RSK.

Much of the area has been the site of a war with massacres of civilians, ethnic cleansing and massive looting. Thousands of people were killed and hundreds of thousands were forced to flee. Destruction turned whole stretches of land into ruins.

The international community set up in 1992 so-called UN safe zones one (United Nations Protected Areas, UNPAs). This calmed the situation somewhat, even if ceasefire agreements were repeatedly broken.

In much of the region in 1995 was in the course of Operation Storm , the state territorial sovereignty of Croatia established. The remaining part of the area in Eastern Slavonia was peacefully integrated within the framework of the UNTAES mission with the Erdut Agreement .

The International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia convicted leaders of the Serbian and Croatian sides of war crimes; the convictions of the Croatian generals were overturned by the appellate court in 2012.

geography

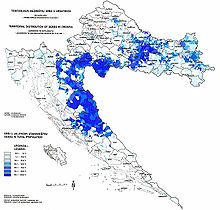

The territory of the Republic of Serbian Krajina was composed of an area from the Banija via the Kordun and the Lika to the hinterland of northern Dalmatia and parts of western and eastern Slavonia . The three parts were only connected to each other via the Serbian-controlled area in northern Bosnia and the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia . The actual limit was the armistice line, which corresponded to the course of the front in early 1992.

population

According to the results of the 1991 census, a total of around 470,000 people lived in the area of the later Republic of Serbian Krajina in the spring of 1991, including 246,000 Serbs , 168,000 Croats and 56,000 members of other nationalities, with the respective regional population distribution in the individual parts of the country later belonging to the RSK 100 rounded) was as follows:

| Serbs | Croatians | other | total | |

| later RSK total | 245,800 (52.3%) | 168,000 (35.8%) | 55,900 (11.9%) | 469,700 |

| UNPA sector north and south | 170,100 (67%) | 70,700 (28%) | 13,100 (5%) | 253,900 |

| UNPA Sector West | 14,200 (60%) | 6,900 (29%) | 2,600 (11%) | 23,700 |

| UNPA East Sector | 61,500 (32%) | 90,500 (47%) | 40,200 (21%) | 192.200 |

Note: This table should only be used as an overview. The fact that the population composition of the area concerned is extremely inhomogeneous and that there were in part significant minorities of one or the other ethnic group in almost every village is ignored.

In the rural regions (Knin, Kordun, Banija), Serbs made up 154,461 people, 67 percent of the population. In Slavonia a total of 200,460 Serbs were counted. This corresponded to 20 percent of the population. In total, this was 61 percent of all Serbs living in Croatia.

The establishment of the Republika Srpska Krajina was preceded by large-scale expulsions (so-called “ ethnic cleansing ”) of over 170,000 non-Serbian residents, mainly Croatians , from the affected areas. An unknown number of civilians were also murdered. Many were also held in prison camps. This was the only way to create a coherent area with a Serb majority.

Living conditions in the “detention centers” are said to have been brutal and characterized by inhuman treatment, overcrowding, hunger, forced labor, inadequate medical care and constant physical and psychological assault, including bogus executions, torture , beatings and sexual assault.

Around 5,000 residents of the eastern Croatian city of Ilok , 20,000 residents of the city of Vukovar and 2,500 residents of the city of Erdut are said to have been forcibly taken to prison camps.

Following the military operation Oluja ("Storm") carried out in the summer of 1995 , during which the Croatian army conquered the territory of the RSK, war crimes and crimes against humanity against civilians were again committed . According to UN statistics, around 200,000 Krajina Serbs fled to the Republika Srpska , Serbia and Montenegro and the UNTAES zone.

history

World War II and Yugoslavia

During the Second World War had Krajina Serbs severe persecution by the Ustashe suffering regime of Croatia, on the other side were Bosniaks and Croats from Serb-monarchist Chetniks pursued that with the Italian fascist occupation forces in the fight against Ustasha and Tito partisans collaborated .

In 1943 the Provisional Government ( ZAVNOH ) declared Croats and Serbs to be equal “state peoples” in Croatia. Even after the amendments to the constitutional laws in Yugoslavia in 1965 and 1974, these rights of the Serbian people were reaffirmed.

Events between 1980 and 1995

A severe economic crisis had developed in Yugoslavia since the 1980s, in the course of which the political system of Yugoslavia was also called into question. The disputes in this regard also had national components, which were connected with the prosperity gap between the republics and the worsening distribution struggles. In 1990 free elections took place in all republics with the exception of Serbia and Montenegro, each of which was won by nationally oriented parties. In Croatia, the then nationalist HDZ ( Hrvatska demokratska zajednica , “Croatian Democratic Union” ) won the majority under Franjo Tuđman . The declared aim of the new government was the greatest possible independence for Croatia within Yugoslavia or international law sovereignty .

This goal was countered by an aggressive policy by the Serbian President Slobodan Milošević . Like other Croatian parties, the HDZ feared military intervention by the Yugoslav People's Army from Serbia. Rumors were spread that Belgrade was already taking measures to “restore order”. H. the suppression of all democratic efforts and national aspirations were planned. This increased serbophobic tendencies in the Croatian public.

The leader of the Serbian party Srpska Demokratska Stranka (SDS), which was only founded in February , Jovan Rašković , initially saw positive prospects for the Serbs in Croatia and tried to distance himself from the nationalist forces in his own party. In talks with Tuđman, he tried to sound out possibilities for a “historical compromise” between Croats and Serbs. Such attempts were soon overshadowed by violent incidents. On May 13, 1990, the Sunday after the parliamentary elections in Croatia, a football match between Dinamo Zagreb and Red Star Belgrade in Zagreb resulted in a big fight with more than a hundred seriously injured. A few days later an attempted assassination of a local SDS official took place in Benkovac . This led to radicalization within the SDS. It suspended the work of its few members in the Croatian parliament.

The government under Tuđman downgraded the approximately 580,000 Serbs living in Croatia in a new constitution from the second state people to a minority. The abolition of the necessary two-thirds majority in nationality-political decisions by the Croatian parliament fueled the Serbs' fears of discrimination and brought back memories of the Ustaša state in World War II. The increasing tolerance of Ustaše symbols, professional discrimination against Serbs, provocative and brutal police action, nationalist agitation, the trivialization of Serbian victims in World War II and growing Serbophobia fueled national emotions. They were fueled by both Croatian and Serbian politicians.

The situation particularly came to a head in the Knin region. Here the balance of power on the Serbian side had shifted in favor of the radical wing in the person of Milan Babić , then mayor of Knin. Babić spoke out in favor of territorial autonomy for the Serb minority. On July 25, 1990, the leadership of the Serbian part of the population around Milan Babić declared the "sovereignty and autonomy of the Serbian people in Croatia" due to the looming Croatian constitutional change and founded a so-called National Council. After road blockades had occurred on the borders of the areas claimed by Serbs during the so-called tree trunk revolution in mid-August 1990 , a referendum organized in the Knin area at the end of August led to the proclamation of the Serbian Autonomous Region Krajina ( Srpska autonomna oblast Krajina , SAO Krajina). The Croatian authorities were denied legitimacy and prevented from doing anything in the Serb-majority areas.

In March 1991 the first violent clashes broke out between the Croatian police on the one hand and Serbian irregulars on the other. The armed incident near the Plitvice Lakes is often cited as the beginning .

On December 19, 1991, the de facto governments of SAO Krajina and the Serb-controlled Eastern Slavonia declared the unification to an independent republic, since the protection of the Yugoslav People's Army was no longer given. At the same time, Croatia and the newly established Republic of Serbian Krajina introduced their own currencies. In the Republika Srpska Krajina, the previous place-name signs in Latin script have been replaced by those with Cyrillic place names.

From January 15, 1992, the independent Republic of Croatia was recognized and the territorial integrity of Croatia was gradually recognized by the then 12 states of the EU , as well as by Austria, Bulgaria, Canada, Malta, Poland, Switzerland and Hungary . Two days earlier, Croatia was recognized by the Holy See before all EU countries . The Republic of Serbian Krajina was and remained an area within the Croatian state territory that was not recognized under international law.

The war in Croatia

In the further course there were also attacks against the civilian population . An estimated 80,000 Croatians and Muslims were displaced from the Serb-controlled areas of Croatia between August and December 1991. In addition to paramilitaries , associations of the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) were also involved in the war . The JNA units, which had withdrawn from Slovenia to Croatia at the end of July, intervened more and more openly on the side of the Serbian minority, which is also supported by special paramilitary units (e.g. the “ Red Berets ” associated with the Serbian government ) were.

Massacres of civilians took place in various places . Landmines laid in the course of the conflict still pose a threat today. After the conquest of the claimed settlement areas in Croatia and the expulsion of the Croatian population had been achieved, Milošević, representing the Serbs, signed a US negotiator on January 2, 1992 Cyrus Vance brokered a truce. On February 21, 1992, the Security Council passed Resolution 743, which resolved the stationing of blue helmet soldiers - the United Nations Protection Force ( UNPROFOR ) - to secure the ceasefire. Accordingly, UNPROFOR had a traditional peacekeeping mandate in Croatia. The JNA then withdrew to the next theater of war, to Bosnia.

Conquest and reintegration by Croatia

At the beginning of 1995 the Z4 plan , a proposal for the peaceful reintegration of the Republika Srpska Krajina into the Croatian state, with guarantees of far-reaching autonomy close to sovereignty, was presented. This was rejected by the Krajina Serbs and instead sought a union with the Republika Srpska and Serbia . As a result, the willingness of western states to support the Croatian side in recapturing their national territory grew.

In the spring of 1995, an agreement between the Croatian government and the Republic of Serbian Krajina provisionally reopened the highway between Zagreb and Slavonia, which runs through the Serbian-controlled western Slavonia . Recurring attacks on travelers were officially taken by Croatia as an opportunity to recapture the territory controlled by the Republic of Serbian Krajina in western Slavonia in May 1995 through the military operation Bljesak ( Blitz ). In retaliation for the attack by the Croats, the then President and Commander-in-Chief of the RSK, Milan Martić, carried out two militarily senseless rocket attacks on the city center of Zagreb on May 2 and 3, 1995 , which left 7 dead and 214 injured among the civilian population. Both events were strongly condemned by the UN Security Council . For this attack, among other things, he was sentenced on June 12, 2007 by the ICTY to 35 years in prison.

After the genocide in Srebrenica became known , the Croatian army conquered further areas in southern Bosnia in Operation Summer '95 at the end of July 1995 and thus encircled the southern part of the Serbian-ruled Krajina from three sides. As a result, during the negotiations on the Z4 plan in Geneva on August 3, the Prime Minister of the Serbian Republic of Krajina , Milan Babić, told Peter W. Galbraith , the US ambassador to Croatia, that he would accept the Z4 plan. This declaration was not accepted by Croatia as Milan Martić refused to accept the plan at all.

On August 4, 1995, the Croatian army launched Operation Oluja , a major offensive against the Republic of Serbian Krajina , which was captured within a few days. On the same day, the Croatian radio broadcast a statement by Tuđman, in which the Serbian people who did not take part in the uprising were called to wait quietly in their homes for the Croatian authorities, without fear for their lives or property. They would be granted all civil rights and local government elections. At the same time it was announced every hour that two safe corridors to Bosnia were open to those wishing to leave the country. The political leadership of the Krajina Serbs had ordered the evacuation in view of the looming defeat and to protect the population. An estimated 150,000 to 200,000 Serbs fled the Krajina in the direction of Bosnia and Serbia, with acts of revenge and war crimes from the Croatian side. According to the ICTY, the decision to evacuate had little or no influence on the exodus of the Serbs, as the population was already on the run at the time of the evacuation decision. Crimes committed by the Croatian army and special police forces, as well as the bombardment of some cities, created a situation of threat and fear in which the population had no choice but to flee. The Croatian historian Ivo Goldstein wrote: “The reasons for the Serbian exodus are complex. Some had to leave their homes because they were forced to flee by the Serbian army, while others feared the revenge of the Croatian army or that of their former Croatian neighbors, who had driven them out and whose houses they had mostly looted (as it turned out later, this was Fear by no means unfounded). "

The general responsible for "Operation Sturm" , who was at times on the run , Ante Gotovina , was sentenced on April 15, 2011 by the ICTY to a prison term of 24 years for war crimes and crimes against humanity . This judgment was overturned by the appellate body in November 2012 and Gotovina was released.

The war in Croatia from the perspective of the final report of the UN Commission of Experts in 1992

"There are a number of indications that the political and military leadership of the former Yugoslavia had prepared for military intervention in Croatia in 1990, possibly before."

The report of the UN Expert Commission also states that

“The Yugoslav Federal Army JNA increased its troop strength in Croatia with the emerging independence movements. Both in tactical terms and in intensity, the role of the JNA was dramatically different from the role it had previously played in the clashes in Slovenia . Local Serb insurgents were supplied directly with weapons and equipment from the JNA's stocks. A special unit for psychological warfare began to carry out plans for provocation and ethnic cleansing at the local level by special units. "

The maximum objective of the JNA was to militarily overthrow Croatian independence efforts and thus preserve the integrity of Yugoslavia or at least (as a minimum objective) to incorporate the area of the RSK into a remainder of Yugoslavia.

According to paragraph D of this document, there were “incidents with bombs and mines” between August 1990 and April 1991, as well as attacks on Croatian police forces, which resulted in regular clashes between Croatian units and Serb paramilitaries.

"By mid-July 1991, the JNA had relocated an estimated 70,000 soldiers to Croatia, ostensibly to create a buffer between the factions."

The fighting escalated and spanned hundreds of square kilometers in Slavonia , Banovina and northern Dalmatia. According to this expert report, the majority of the local JNA leaders in areas that were sparsely populated by Serbs were not oriented towards violence. The JNA and the Serbian paramilitary forces swore the Serb insurgents to affiliate the RSK with the rest of Yugoslavia.

War tactics of the JNA according to the final report of the UN expert commission

The JNA operations in Croatia took place in three phases: In the first phase, bridges over larger rivers were taken and Croatian police units “neutralized”. In the second phase, the JNA tried to interrupt the traffic connections between the capital Zagreb and the war zones. In the third phase, ethnic cleansing of non-Serbs was carried out in the areas under Serbian control .

After the armistice in November 1991, the JNA withdrew some of its weapons from Croatia and moved its units to Bosnia-Herzegovina .

Armistice and UN protection zones

An armistice was signed in early 1992 with international mediation . Accordingly, the Yugoslav army committed itself to withdraw its troops from Croatia . In the disputed territories was a peacekeeping force of the United Nations ( UNPROFOR ) stationed after the Vance-Owen plan was accepted by both parties. A total of four protection zones were created : Sector North, South, East and West. The UN sent 14,000 soldiers to these areas. The Serbian-controlled parts remained part of Croatia under international law. Its final status would later be decided in negotiations between the Croatian government and the local Serbs.

The armistice line became in fact a state border between Croatia and the Krajina Republic, which could only be crossed with great danger. The negotiations on the opening of the traffic routes and the return of refugees and displaced persons did not progress because the Serbian side was not prepared to allow the displaced persons to return and, in addition, to re-recognize the Serbs as a second national people (instead of a minority) within Croatia or the Demanded recognition of the Republic of Serbian Krajina by Croatia. The leadership of the Republic of Serbian Krajina at that time saw the control of the most important traffic connections from northern Croatia to Dalmatia through areas in Lika and northern Dalmatia and to Slavonia through the area under its control in western Slavonia as their main means of exerting pressure on the Croatian government on this issue .

In June 1992, despite the presence of the UN, the fighting broke out again, and in the following year the armed clashes, some of which were severe, continued.

Geographical and economic problems

The economic situation of the Republic of Serbian Krajina remained precarious throughout its existence. It had no contiguous territory; the connection between its core area, which stretched from Knin in the south along the Croatian-Bosnian border to Petrinja , and the Serbian-controlled area in western Slavonia could only be maintained through the Bosnian Serbs' route via the Republika Srpska ; Eastern Slavonia could only be reached by a long detour via the rest of Yugoslavia.

Reliable economic data are not available. According to the temporary Prime Minister Borislav Mikelić , only 36,000 of the 430,000 inhabitants were in regular employment. Due to the sanctions, there was almost no tourism anymore. Due to the separation from Croatia, the already scarce industry lost an important sales market. There was also a lack of qualified workers and managers. Overall, the dramatic economic situation led to an increased development of a shadow economy and increased crime rates.

The wish repeatedly expressed by the leadership of the Republic of Serbian Krajina to merge into one state with the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia formed by Serbia and Montenegro , was rejected by the leadership in Belgrade , as Serbia would not find the way to a future peace agreement with such a step wanted to obstruct with Croatia.

The UNTAES interim administration in Eastern Slavonia

From the Republic of Serbian Krajina only the Serbian-controlled area in Eastern Slavonia remained. This was peacefully reintegrated into the Republic of Croatia as part of an agreement between Croatia and Serbia . For this purpose, it was placed under an interim administration of the United Nations ( United Nations Transitional Administration for Eastern Slavonia, Baranja and Western Syrmia / UNTAES ) from 1996 to 1998 .

Demographic consequences of war and return of refugees

If you compare the censuses of 1991 and 2001, the following picture emerges:

- In 1991 (last Yugoslav census) the proportion of the population of Serb nationality in the Republic of Croatia was approx. 582,000 (12.2%).

- In 2001 there were still about 201,000 Serbian citizens (4.5%) officially registered in Croatia . Many of them, however, still live abroad and have only registered as residents in Croatia in order to protect existing property claims and to secure the pension payments to which they are entitled, which until spring 2004 were only paid to Serbian pensioners within Croatia.

The reintegration of the Serbian population in Croatia is in some cases still slow. International organizations, however, note an increasing improvement in the situation. In 2000 there were isolated attacks on returnees. Many returnees are still fighting against the expropriation of their land, houses and apartments. The construction or renovation of houses of Serbian returnees is financed by international funding programs and projects on the part of the Croatian government. In 2005, the Croatian government launched a media campaign in Croatia's neighboring countries to encourage people to return. Overall, however, the situation of the Serbian returnees is difficult, as some resentments still prevail.

In some areas, such as the Knin area , Croatians from Bosnia , Vojvodina and Kosovo were resettled in the former houses of the Serbian population. This still leads to a precarious situation with regard to the return of expropriated property and in some cases increased resentment towards the Serbian returnees.

By January 2005, around 118,000 Serbs had returned to Croatia. Some of the Serbs from Croatia have sold their houses and land and do not want to return. Another part exchanged houses and land with Croats from Vojvodina . So far around 40,000 people have been relocated in this way.

The Croatian government granted a general amnesty to the approximately 50,000 Serbs directly involved in the armed uprising , provided that no direct war crimes can be proven individually.

The question of reparations and compensation has so far hardly been addressed in the international context or only dealt with superficially.

War Crimes Tribunal

Former President of the Republic of Serbian Krajina, Goran Hadžić , was charged with war crimes and crimes against humanity by the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) in The Hague in May 2004 . He went into hiding shortly after the charges became known and was not arrested until July 20, 2011. On July 12, 2016, he died of a brain tumor without a previous judgment.

On June 29, 2004, the ICTY sentenced Milan Babić to 13 years in prison for crimes against humanity . The former leading politician of the RSK had confessed to having persecuted people of other population groups for political reasons in 1991/1992. Babić had been charged with participating in actions aimed at driving non-Serbs from around a third of Croatian territory. Babić hanged himself in his cell in The Hague on the evening of March 5, 2006 and was buried in Belgrade on March 21, 2006.

On June 12, 2007, Milan Martić , the last president of the RSK, was charged by the ICTY on 16 of 19 counts in relation to war crimes and crimes against humanity in the so-called “SAO Krajina”, which was later renamed the Republic of Serbian Krajina Found guilty and sentenced to 35 years in prison.

Ante Gotovina , who was arrested in December 2005 after a long flight and handed over to the ICTY, protested at his first appearance in court in The Hague on December 12, 2005, that he was innocent in connection with war crimes and crimes against humanity that occurred under his command should be. On April 15, 2011, Ante Gotovina was sentenced to 24 years in prison by the International Criminal Court. The court also found the co-accused ex-general Mladen Markač guilty: he was imprisoned for 18 years. General Ivan Čermak, however, was acquitted.

When the judgment against Gotovina was pronounced by the judges of the ICTY, Tuđman was also mentioned. One of the judges emphasized: "The then President Franjo Tuđman was the main leader of this criminal organization" and "He wanted the depopulation of the Krajina" .

The judgment was appealed on May 16, 2011.

On November 16, 2012, Gotovina and Markač were acquitted of all charges and released from custody. The Appeals Chamber decided unanimously that the lower court's assessment that artillery hits more than 200 meters away from a target considered legitimate as evidence of unlawful attacks on the towns in Krajina was incorrect. By majority vote, it was found that the evidence was insufficient to consider the shelling of the cities ordered by Gotovina and Markač to be illegal. Since the first instance conviction for the formation of a criminal association to expel Serbs from the Krajina is based on the illegality of the artillery attacks and the first instance did not establish a direct involvement in Croatia's policy of discrimination, this guilty verdict should also be set aside.

Mine situation in the formerly contested areas

In the areas contested until 1995 there is still a risk from landmines . This is especially true of the front lines of the time. It is estimated that around 90,000 mines are still scattered in Croatia. 736 square kilometers are explicitly designated as mine-contaminated. Since no site plans have been drawn up over the minefields, mine clearance is very time-consuming. The following areas are affected:

- Eastern Slavonia (30 to 50 km from the border with Serbia and on the border with Hungary , especially areas around Vukovar and Vinkovci );

- West Slavonia ( Daruvar , Pakrac , Virovitica );

- the western and southwestern border area with Bosnia (the area south of Sisak and Karlovac , east of Ogulin , Otočac , Gospić , on the eastern outskirts of Zadar and in the hinterland of the coast between Senj and Split and in the mountains southeast of Dubrovnik ).

politics

Despite the short existence of the RSK, there were a large number of self- appointed presidents or heads of government between 1991 and 1995, or elections controlled by Belgrade .

List of presidents of the RSK

- Milan Babić , President (December 19, 1991 to February 16, 1992)

- Mile Paspalj , Interim President (February 16, 1992 to February 26, 1992)

- Goran Hadžić , President (February 26, 1992 to January 25, 1994)

- Milan Martić , President (January 25, 1994 to August 7, 1995)

List of heads of government of the RSK

- Milan Babić , Prime Minister (April 30, 1991 to December 19, 1991)

- Dusan Vjestica , Prime Minister (December 19, 1991 to February 26, 1992)

- Zdravko Zecević , Prime Minister (February 26, 1992 to April 21, 1993)

- Djordje Bjegović , Prime Minister (April 21, 1993 to March 17, 1994)

- Borislav Mikelić , Prime Minister (March 17, 1994 to July 27, 1995)

- Milan Babić , Prime Minister (July 27, 1995 to August 7, 1995)

List of UNTAES administrators

- Jacques Paul Klein (USA) (January 17, 1996 to August 1, 1997)

- William G. Walker (USA) (August 1, 1997 to January 15, 1998)

See also

literature

- Nina Caspersen: Contested nationalism: Serb elite rivalry in Croatia and Bosnia in the 1990s , excerpts online

- Andrea Friemann: Focus Krajina. Ethnic cleansing in Croatia in the 1990s. In: Holm Sundhaussen: Power of Definition, Utopia, Retaliation: “Ethnic Cleansing” in Eastern Europe in the 20th Century, LIT Verlag Münster, 2006, p. 169ff., Excerpts online

- Hannes Grandits: Krajina: Historical Dimensions of the Conflict , in: East-West-Counter-Information, No. 2/1995, full text online

- Hannes Grandits, Carolin Leutloff-Grandits: Discourses, actors, violence - considerations on the organization of war escalation using the example of Krajina in Croatia 1990/91 . In: Political and ethnic violence in Southeast Europe and Latin America., (Eds.): W. Höpken, M. Riekenberg. Böhlau, Cologne 2001.

- Hannes Grandits / Christian Promitzer: "Former Comrades" at War. Historical Perspectives on "Ethnic Cleansing" in Croatia , in: Joel M. Halpern / David A. Kideckel (eds.): Neighbors at War. Anthropological Perspectives on Yugoslav Ethnicity, Culture and History, University Park, PA 2000, pp. 125ff. excerpts online

- Holm Sundhaussen: The contrast between historical rights and rights of self-determination as a cause of conflicts: Kosovo and Krajina in comparison , in: Nationality conflicts in the 20th century: A comparison of causes of inter-ethnic violence. Edited by Philipp Ther u. Holm Sundhaussen. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz 2001, pp. 19–33, excerpts online

Web links

- UN Security Council resolution 1009 Session 3563 (S / RES / 1009) of 10 August 1995 (English)

- Report of the ICRC about the attack on Knin in August 1995 by the Croatian Army (English)

- Final report of the UN Commission of Experts 1992

- The politics of creating a "Greater Serbia": nationalism, fear and repression, English, source: Final report of the United Nations Commission of Experts

Individual evidence

- ↑ z. B. Nina Caspersen: From Kosovo to Karabakh: International Responses to De Facto States . In: Southeast Europe . No. 56 (1) , 2008, pp. 58-83 .

- ^ Robert Soucy: Fascism (politics) - Serbia . Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved July 23, 2011.

- ↑ Weighing the Evidence - Lessons learned from the Slobodan Milošević trial , Human Rights Watch . 12/13/2006. Retrieved July 23, 2011.

- ↑ Mediji i rat: Kako je “Politika” izveštavala 1992. godine (2) Politika 27. ožujka 1992: Poslanici su aplauzom potvrdili pravno zaokruženje četvrte republike na tlu treće Jugoslavije .

- ^ Decision of the ICTY Appeals Chamber; April 18, 2002; Reasons for the Decision on Prosecution Interlocutory Appeal from Refusal to Order Joinder; Section 8

- ↑ a b c No “criminal enterprise” , orf.at of November 16, 2012, accessed on November 16, 2012.

- ↑ ICTY indictment against Slobodan Milošević, paragraph 69 (PDF; 3.5 MB)

- ↑ Holm Sundhaussen: The contrast between historical rights and rights to self-determination as a cause of conflicts: Kosovo and Krajina in comparison. P. 22, cf. literature

- ↑ Source for the figures and other content: ICTY indictment against Slobodan Milošević, paragraph 36k (PDF; 3.5 MB)

- ↑ http://www.un.org/documents/ga/docs/50/plenary/a50-648.htm

- ↑ ZAVNOH documents on crohis.com

- ↑ Hannes Grandits and Carolin Leutloff: Discourses, actors, violence: the organization of war-escalation in the Krajina region of Croatia 1990-91 , in: Potentials of disorder: New Approaches to Conflict Analysis. Edited by Jan Koehler and Christoph Zürcher, Manchester University Press 2003

- ↑ Census in Croatia 1991, population by nationality , dzs.hr, page 13 v. 34, Retrieved September 21, 2019

- ↑ Holm Sundhaussen: The disintegration of Yugoslavia and its consequences, in: "The Parliament" with the supplement "From Politics and Contemporary History", issue 32 of August 4, 2008 online

- ↑ Dunja Melčić (ed.): The Yugoslavia War . Westdeutscher Verlag, Opladen / Wiesbaden 1999, ISBN 3-531-13219-9 , p. 545.

- ↑ ICTY indictment against Milan Babić (PDF; 104 kB)

- ^ Safety instructions from the German Foreign Office on Croatia

- ↑ David Rieff: Slaughterhouse. Bosnia and the failure of the West, Munich 1995, p. 20

- ↑ Filip Slavkovic: Ten years after the end of the Croatian War: Memory of the decisive offensive , Deutsche Welle of August 4, 2005, accessed on November 18, 2012.

- ^ Raymond Bonner: Serbs Said to Agree to Pact With Croatia , New York Times, August 4, 1995 (English), accessed November 18, 2012.

- ↑ Norbert Mappes-Niedik: Croatia, the land behind the Adriatic backdrop , Berlin 2009, p. 156

- ^ Holm Sundhaussen: The disintegration of Yugoslavia and its consequences. In: The Parliament. with the supplement From Politics and Contemporary History. Issue 32 from August 4, 2008 online

- ↑ a b icty.org: Judgment Summary for Gotovina et al. (PDF; 90 kB) , accessed April 15, 2011

- ^ Ivo Goldstein: Croatia: A History. Pp. 253-254. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers 1999, ISBN 1-85065-525-1

- ↑ The military structure, strategy and tactics of the warring factions , Appendix III of December 28, 1994 of the final report of the UN Security Council on the implementation of Resolution 780, Section C. The conflict in Croatia ( Memento of July 28, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ The military structure, strategy and tactics of the warring factions , Appendix III of December 28, 1994 of the final report of the UN Security Council on the implementation of Resolution 780, Section D. Forces operating in Croatia ( Memento of July 28, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Filip Svarm: The Krajina Economy Vreme, 15 August 1994

- ↑ Amnesty International Germany, Annual Report 2004, Section Croatia

- ^ Indictment against Milan Babić

- ↑ ICTY - Case Information Sheet (English; PDF; 300 kB)

- ^ ORF: 24 years imprisonment for Croatian ex-General Gotovina

- ^ Ex-Croat generals lawyers move to appeal war crimes verdicts ( Memento of November 9, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) of May 16, 2011

- ↑ Appeals Chamber acquits and Orders Release of Ante Gotovina and Mladen Markač , press release of the International Criminal Court of 16 November 2012 called on 16 November 2012 found.

- ↑ Summary of the appeal judgment (PDF, 107 kB, English)

- ↑ Detailed appeal judgment (PDF, 1 MB, English)

- ↑ Mine situation on the website of the Croatian Center for Demining (HCR), accessed on April 24, 2012

- ↑ Travel and safety information for Croatia from the Federal Foreign Office, accessed on April 24, 2012

- ↑ Norman L. Cigar, Paul Williams: Indictment at the Hague: The Milosevic Regime and Crimes of the Balkan Wars, NYU Press, 2002, p. 294 [1]