Ambrose of Milan

Ambrose of Milan (* 339 in Augusta Treverorum , Roman province of Gallia Belgica , † April 4, 397 in Mediolanum , Gallia cisalpina ) was elected Bishop of Milan as a Roman politician . He is one of four Latin Doctors of the Church of the Late Antiquity the Western Church , was the younger brother of the Holy Marcellina and Satyrus of Milan and carries since 1295 the honorary title of church father .

Life

prefect

Ambrosius came from a noble family of the Roman Senate aristocracy, but was not baptized, which was not uncommon in late antiquity . His father Aurelius Ambrosius was prefect of Gallia Narbonensis . After his early death in Rome, Ambrosius was earmarked for the civil service career and was trained accordingly. The place where, according to tradition, he lived with his sister, Saint Marcellina , is now the church of Sant'Ambrogio della Massima . In 365 he obtained one of the coveted approvals as a lawyer in court and finally served in Sirmium under the Praetorian prefect Sextus Petronius Probus , one of the leading men of his time. Ambrosius represented his legal cases so skillfully that Probus appointed him 370 as his assessor. About 372/73 he was entrusted by this with the prefecture of the province Aemilia-Liguria ( Ämilien and Liguria ). The seat of the province was Milan, which at that time also served as an imperial residence.

The way to the bishop

The diocese of Milan , like the rest of the church at that time, was deeply divided between Trinitarians and Arians . When in 374 (after the death of the Arian Auxentius of Milan ) a bishopric was about to be elected, the popular and respected prefect personally went to the basilica , where the election was to take place, in order to prevent a possible riot in this crisis situation. According to tradition, his address was given by the interjection of a child Ambrosius episcopus! ("Ambrosius should become bishop!") Interrupted, whereupon he was unanimously elected bishop.

In this situation, Ambrose appeared to be a suitable candidate because he was known to the Trinitarians as their sympathizer, but also to the Arians because of his theological neutrality as an acceptable politician. However, he himself voted vigorously against his choice, although it is a literary topos. He saw himself in no way prepared for such an office: as a catechumene, he was still preparing for baptism . Ambrosius only gave in to imperial intervention. Within a week he received the sacraments of baptism and ordination as deacon and priest , so that nothing stood in the way of his episcopal ordination . According to Paulinus and Rufinus , Ambrosius only accepted the election after a relatio to Emperor Valentinian I ; After all, he was in imperial service, which he could not quit without consulting.

Studies and Liturgy

Ambrosius acquired theological foundations, studied the Bible and Greek authors such as Philo , Origen , Athanasius and Basil of Caesarea , with whom he was also in correspondence. He used the newly acquired knowledge as a preacher, particularly interpreting the Old Testament . His earlier acquired knowledge of rhetoric and Greek , which at that time were rare in the Western Roman Empire, were of great advantage.

In the liturgy he introduced the Ambrosian chant named after him . His character, his sermons and biblical interpretation impressed the rhetorician Augustine of Hippo , who did not speak Greek, so much that he was baptized by him on Easter 387, where, according to tradition, the Gregorian Te Deum originated as antiphon.

Fight against Arianism

Contrary to the expectations of the Arians , Ambrosius successfully advocated the Nicene direction. In his long struggles against the Arians, who particularly dominated the court of Emperor Valentinian II in Milan, Ambrosius used alternating theological and political methods. First he used his influence to push back the Arians in the Illyrian church administration: In 381, at the regional synod of Aquileia , he took care of the deposition of the Illyrian bishop Palladius and his presbyter Secundinus. When the Arians presented to the imperial court to get at least one church in Milan outside the city gates, Ambrosius intervened and mobilized his supporters among the Milanese population. This type of "civil disobedience", an unheard of affront in the autocratic Roman Empire of late antiquity, was justified by the fact that it was not the emperor but the church officials who had to decide in religious matters. In particular, the imperial mother Justina showed sympathy for the Arian side, but could not prevail against the self-confident Ambrosius. In 382 (or 383) Ambrose also succeeded in persuading Gratian to give up the title of Pontifex Maximus and to cease state donations to the pagan temples. In the dispute over the Victoria altar, he remained victorious over Quintus Aurelius Symmachus , the altar was removed from the Roman Curia.

Around 387, Ambrose convinced his friend Gaudentius of Brescia to accept the office of bishop. Like Ambrose himself, Gaudentius originally had reservations about assuming the episcopal dignity.

In 390, Ambrose convened a northern Italian synod of bishops, which, like Pope Siricius before , condemned the teachings of Jovinian . Jovinian had denied the higher merit of a life according to the evangelical counsels and the perpetual virginity of Our Lady .

Influence on Emperor Theodosius I in favor of the church

In 388, Ambrose prevented the punishment ordered by Emperor Theodosius I of a bishop who had incited a crowd in Kallinikon on the Euphrates to a pogrom and to burn down the synagogue there. Theodosius initially understood the outbreak of violence as a regulatory problem, as an uproar that the Roman state could of course not tolerate. The emperor therefore wanted to hold the Christian arsonists responsible for their actions; he spared the responsible bishop, but asked him to rebuild the destroyed synagogue. Ambrosius, however, now demanded in a letter that all looters and violent criminals should go unpunished. He interpreted the process as a conflict between Christianity and Judaism, in which the emperor could of course not take the side of the Jews; In particular, it is completely unacceptable to ask the church to rebuild the destroyed synagogue:

“The Comes Orientis reports on the fire in a synagogue caused by the local bishop. You have ordered that the others should be punished and that the bishop personally see to the restoration of the synagogue. I do not insist that the bishop concerned should have waited for the report. After all, it is the bishops who keep angry masses in check and are concerned about peace, unless they themselves are irritated by a blasphemy or an insult inflicted on a church ... Should [in all seriousness] be a place for the unbelief of the Jews be created at the expense of the Church ...? Should the inheritance of Christians, thanks to the grace of Christ, increase the treasure of the unbelievers ...? Should the Jews put this inscription on the front of their synagogue: 'The Temple of Injustice, built from the booty taken from Christians'? "

The letter was initially unsuccessful, but the respected bishop then forced the emperor to relent diplomatically by publicly criticizing him in the service and refusing to take communion until the emperor had given in. The process shows how Ambrosius used his episcopate specifically to influence the baptized emperor in his own way. Theodosius finally had to give in. The emperor did not question the legality of his original judgment, as this would have amounted to a complete loss of face, but in the sense of the ancient ideal of rulers, he showed gentleness and mercy towards the Christian violent criminals, who remained unpunished. Although the protection of the Jews in the Roman Empire was once again expressly confirmed by law, the synagogue in Kallinikon was not rebuilt. This set a precedent which, in case of doubt, placed the interests of the Christian religion above the law and threatened to undermine the imperial legal protection for the Jews, which had been a matter of course until then, as well as the overall authority of the Roman ruler as the guardian of inner peace.

Political activity

In 390, Ambrose even forced Theodosius to repent in public for the massacre of Thessaloniki under threat of excommunication . This action cannot, however, be compared with the penitential walk of Henry the Fourth to Canossa , even if some authors of polemics in the eleventh century compare both events - with Heinrich it was about a power struggle between the emperor and the Pope , with Theodosius about the pastoral question of whether the Emperor is above a clear sin or, like everyone else in this situation, must repent for it ( the emperor is in the church, not above the church ). The emperor himself used the opportunity to symbolically portray himself as a repentant sinner and thus to consolidate his reputation again.

Ambrosius was not only involved in canonical matters, but was also politically challenged by his prominent position as bishop of the Milan residence. So he faced the usurper Magnus Maximus , who threatened Italy from Gaul, as ambassador Valentinian II. The Theodosian decrees, which raised Christianity in the Trinitarian form to the state religion in 391, were probably influenced significantly by Ambrose. When Eugenius was raised , Ambrosius behaved distantly towards him, not least because of Eugenius' promotion of the old cults (although some statements from the sources are certainly exaggerated).

death

Ambrosius died after an episcopate of 23 years on the eve of Easter 397. His successor in the episcopate was Simplicianus. He himself was buried and venerated in the Basilica of Sant'Ambrogio named after him .

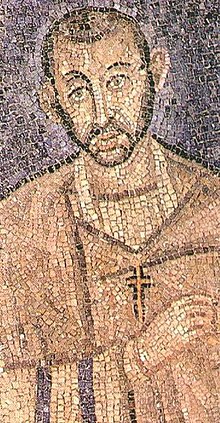

Ambrose's mosaic in the church of Sant'Ambrogio is one of the few halfway realistic portraits of a cleric of antiquity (see picture above); the slight shift in the left eye was confirmed by examining his corpse.

theology

In his interpretation of the Bible, Ambrosius used Philonic models and applied the exegetical method of allegory developed by Origen in Alexandria , which gives the Bible text a threefold meaning: the literal sense, the moral sense and the mystical sense.

As a theologian, Ambrose developed fewer ideas of his own than interpreted the texts of the Eastern Church Fathers for the Latin world - an essential ecclesiastical factor for the theological development of the Western Church, since practically all the great theologians before Ambrose came from the East or wrote in Greek.

An indication of its importance for the Catholic Church is that Ambrose is quoted over twenty times in the Catechism of the Catholic Church (only surpassed by Augustine and Thomas Aquinas ).

Like the Doctors of the Church Jovinian , Augustine and Hieronymus , he valued celibacy higher than the status of marriage .

His contribution to theology was judged differently by contemporaries. Hieronymus writes that Ambrose is a bird that adorns itself with strange feathers and turns good Greek into bad Latin. Augustine, on the other hand, explains that the treatise on the Holy Spirit is written in a simple style, since the subject does not require linguistic beauty but arguments that move the minds of its readers.

The Ambrosian liturgy recognizes the washing of feet as a sacrament .

See also: Ambrosian rite

Adoration of saints

St. Ambrose is the patron saint of the cities of Milan and Bologna , the shopkeepers , beekeepers , wax pullers and gingerbread bakers , bees , pets and learning . Its attributes are beehive , book and scourge . His feast day in the Armenian, Catholic, Anglican and Orthodox Churches as well as in the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America and the Lutheran Church - Missouri Synod is December 7th (day of his ordination as a bishop), in other Protestant churches, such as the member churches of the Evangelical Church in Germany , April 4th (day of death, is also celebrated in the Orthodox Church).

The veneration of the saint as the patron saint of beekeepers is explained by tradition, according to which a swarm of bees is said to have settled on his face in the saint's childhood . The bees crawled into the child's mouth and nourished it with honey. This was interpreted as a sign from God and an indication of a great future for the child. Bees are honored in the song of the Exsultet for their honey, which has always been valuable, and for the wax, the only material for making candles for centuries , and are both a symbol of Christ and a symbol of the consecrated virgins and diligence. In Austria December 7th is also the day of honey because of the commemoration of the saint.

The peasant rule corresponding to the remembrance day on April 4th is:

- If Ambrosius is beautiful and pure, Saint Florian (4 May) will be a savage.

Works and Tradition

- De fide ad Gratianum (On Faith) - Treatise against Arianism, written for Emperor Gratianus

- De institutione virginis et S. Mariae virginitate perpetua (Institution of the Virgin and the perpetual virginity of St. Mary; Christian ethical writing on virginity) around 392.

- DIVI AM- || BROSII EPISCOPI MEDIO- || LANENSIS COMMENTARII IN || omnes Diui Pauli epistolas, ex restitutio || ne D.Erasmi diligenter recogniti. || CVM INDICE. || Cologne: Johann Gymnich I. , 1530. Digitized edition of the University and State Library Düsseldorf

- Epistolae ad principes: Almae Congregationi electorali BV Mariae ab angelo salutatae in strictam oblatae . Dusseldorpii: Stahl, 1787. Digitized edition of the University and State Library Düsseldorf

- De Nabuthe Iezraelita (About the Israelite Nabuth; homily against greed) Around 389. Transmitted in a manuscript from the 6th century in Parisinus lat. 1732. Translation by J. Huhn (Freiburg 1950).

- De officiis ministrorum (On the duties of church servants; Christian doctrine of virtue, imitation of Cicero's writing de officiis. First Christian doctrine of virtue) Written 388/389. Handed down in two manuscripts from the 8th / 9th centuries. and 9th century in collections Monacensis lat. 14.641 and Herbipolitanus (Würzburg) Ms. theol. 7. German translation by JE Niederhuber: The doctrine of duty and selected smaller writings of the Holy Doctor of the Church Ambrose of Milan . In: Library of the Church Fathers, Ambrose of Milan. Selected Writings Vol. III, Kempten, Munich 1917. online (rtf; 799 kB)

- De poenitentia (treatise on penance in two books)

- De sacramentis (on the sacraments; treatise on baptism, confirmation and the Eucharist in 6 books) manuscript from the 7th / 8th centuries. Century in Sangallensis 188. Lat-German edition of Ambrosius by J. Schmitz: About the sacraments / About the mysteries . Freiburg 1990, (cart .: ISBN 3-451-22103-9 ; born: ISBN 3-451-22203-5 )

- De Tobia (About Tobias; Homily Against Usury.) Around 375/376. Handed down in a manuscript from the 6th century in Parisinus lat. 1732.

- De virginibus ad Marcellinam sororem (About the virgins to Sister Marcellina; Christian-ethical writing on virginity in three books) Around 377/378. Translation by Johannes Evangelist Niederhuber: About the virgins three books . In: The Holy Church Father Ambrosius selected writings vol. 3; Library of the Church Fathers, 1st row, Volume 32. Kempten; Munich 1917.

- De virginitate (About the virginity; Christian-ethical writing about the virginity) Translation by Johannes Evangelist Niederhuber: About the virgins three books . In: The Holy Church Father Ambrosius selected writings vol. 3; Library of the Church Fathers, 1st row, Volume 32. Kempten; Munich 1917.

- Epistulae (letters; collection of 91 letters in 10 books based on the model of Pliny the Younger; expert opinions, memoranda, theological problems and a letter to Valentinian I about pagan religion)

- Exhortatio virginitatis (exhortation to virginity; Christian ethical writing on virginity) Translation by Johannes Evangelist Niederhuber: About the virgins three books . In: The Holy Church Father Ambrosius selected writings vol. 3; Library of the Church Fathers, 1st row, Volume 32. Kempten; Munich 1917.

- Explanatio Symboli ad initiandos (interpretation of the creed for baptismal people; dogmatic script)

-

Hexaemeron (six-day work; exegesis on Genesis 1,1-1,26; reception of the work of the same name by Basil) 386/387. The oldest surviving manuscript dates from the 8th century in Cantabrigensis Coll. corp. Christi 193. German translation by Johannes Evangelist Niederhuber in: Library of the Church Fathers . Volume 17. Munich 1994.

- Hexameron . Guldenschaff, Cologne around 1480 ( digitized edition )

- Hymni (hymns; collection of 14 hymns with theological, spiritual and ethical content; the authenticity of some has been disputed)

- Orationes (speeches; 5 speeches, including 4 funeral speeches, two for the brother, one for Emperor Valentinian II and one for Emperor Theodosius I.)

- MS-B-204 - Ambrosius Mediolanensis. Petrus Blesensis. Johannes Gerson et alia (theological collective manuscript). Tertiarerkonvent St. Janskamp, Vollenhove [around 1465-1470] ( digitized version )

The first complete edition was obtained by Johann Auerbach in 3 volumes (Basel 1492). The best complete edition is the Mauriner edition by J. du Freshness and N. de Nourry in 2 volumes (Paris 1686–1690)

- Expositio in Lucam Lukas commentary (excluding the story of suffering) BKV2 series 1, volume 21

The Latin texts of some hymns and hymns , which are sung in the Catholic and Protestant Churches to this day , also come from Ambrose . B.

- Now come, the Gentile Savior / Come, you Savior of all the world ( Veni redemptor gentium ),

- Exalted creator of all things' ( Aeterne rerum conditor ),

- You creator of all beings ( Deus, creator omnium ),

- You shine from God's glories ( Splendor paternae gloriae ).

According to tradition, Augustine and Ambrosius are said to have written and composed the Te Deum together . When Augustine received the sacrament of baptism as an adult, Ambrose is said to have intoned this hymn and Augustine replied to it in verse .

literature

- Eric Chevalley: Ambrose (Saint). In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland . June 17, 2002 , accessed December 15, 2019 .

- Markus Löx: monumenta sanctorum. Rome and Milan as centers of early Christianity: the cult of martyrs and church building under the bishops Damasus and Ambrose, Late Antiquity - Early Christianity - Byzantium, Series B: Studies and Perspectives 39 . Wiesbaden 2013.

- Ernst Dassmann : Ambrosius of Milan. Life and work . Stuttgart 2004.

- Adolf Jülicher : Ambrosios 7 . In: Paulys Realencyclopadie der classischen Antiquity Science (RE). Volume I, 2, Stuttgart 1894, Sp. 1812-1814.

- Christoph Markschies : Ambrosius of Milan and the theology of the Trinity . Tübingen 1995.

- Christoph Markschies: Ambrosius of Milan . In: S. Döpp, W. Geerlings (ed.): Lexicon of ancient Christian literature. Herder, Freiburg i. Br. U. a. 1998, pp. 13-22.

- Neil B. McLynn: Ambrose of Milan. Church and court in a Christian capital . Berkeley 1994.

- Friedrich Wilhelm Bautz : AMBROSIUS. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 1, Bautz, Hamm 1975. 2nd, unchanged edition Hamm 1990, ISBN 3-88309-013-1 , Sp. 142-144.

- Angelo Paredi: S. Ambrogio e la sua età . Terza edizione ampliata, Milano: Hoepli 1994.

- Thomas Graumann: Ambrosius of Milan . In: M. Vinzent (Ed.): Metzler Lexikon Christian Thinker. Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2000, pp. 21-25.

- Fabian Schulz: Ambrosius, the emperors and the ideal of the Christian counselor , in: Historia 63 (2014), pp. 214–242.

- Klaus & Michaela Zelzer: Ambrosius, Benedikt, Gregor. Philological-literary-historical studies. Edited by Klaus Zelzer. LIT, Vienna 2015 (Spirituality in Dialog 6).

Web links

- Literature by and about Ambrosius of Milan in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Ambrosius of Milan in the German Digital Library

- Works by Ambrosius of Milan in the complete catalog of incunabula

- Entry on Ambrosius of Milan in the Rhineland-Palatinate personal database

- Christian Classics Ethereal Library, works by Ambrosius (English)

- various works (Latin)

- various works (Latin)

- Hymni Ambrosii (Latin)

- Letter from Basil of Caesarea to Ambrosius (English)

- Complete works of Migne Patrologia Latina with table of contents

- Works from the BKV - Library of the Church Fathers (German)

Remarks

- ↑ Augusta Treverorum, today's Trier

- ↑ Mediolanum, today's Milan

- ↑ Detlef Liebs : The jurisprudence in late antique Italy (260-640 AD) (= Freiburg legal-historical treatises. New series, volume 8). Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1987, p. 55.

- ↑ McLynn, Ambrose of Milan (Berkley 1994) 42 note 160

- ↑ Paul. Med. Vita Ambr. 8, 2-9.

- ↑ Rufin. hist. 2.11.

- ^ Peter Kritzinger: The Cult of Saints and Religious Processions in Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. In: Sarris Peter u. a. (Ed.), An Age of Saints ?. Leiden: Brill, 2011, 36-48.

- ↑ MPL 16, ep. 40.6.10, cit. after Adolf Martin Ritter : Old Church, Church and Theological History in Sources. Vol. 1, Neukirchen 1977, p. 187

- ↑ Hans von Campenhausen, Latin Church Fathers, 5th edition Stuttgart a. a. 1987, p. 100.

- ↑ Cod. Theod. 16.8.9.

- ↑ On the general processes, cf. Ulrich Gotter : Between Christianity and State Reason. Roman Empire and Religious Violence . In: Johannes Hahn (Ed.): Late Antique State and Religious Conflict . De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2011, p. 133 ff.

- ^ Oskar Panizza : German theses against the Pope and his dark men. 'With a foreword from MG Conrad . New edition (selection from the “666 theses and quotations”). Nordland-Verlag, Berlin 1940, p. 33 f.

- ^ Ambrose of Milan in the ecumenical encyclopedia of saints

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Dionysius Mariani |

Archbishop of Milan 374–397 |

Simplicianus Soresini |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Ambrose of Milan |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Roman politician, bishop and doctor of the church |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 339 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | trier |

| DATE OF DEATH | April 4, 397 |

| Place of death | Milan |