Vote of confidence

The confidence is in many parliamentary democracies one instrument Government to discipline the Parliament . A government can submit it to parliament in order to determine whether it is still fundamentally in line with its position, and thus clarify serious conflicts. A negative result often leads to the resignation of the government or to new elections .

Germany: federal level

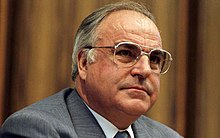

In Germany , one speaks of a vote of confidence within the meaning of Article 68 of the Basic Law (GG) when the Federal Chancellor applies to the Bundestag to express confidence in him. The questions of trust by Helmut Kohl in 1982 and Gerhard Schröder in 2005 used the scope of the constitution in a way that was not intended by the founding fathers. Both Chancellors had a majority in the Bundestag and still asked the vote of confidence in order to dissolve parliament and hold new elections by losing the vote. What Helmut Kohl achieved in 1982/83, Gerhard Schröder did not achieve in 2005. The Schröder government was replaced by the Merkel government.

The difference to the constructive vote of no confidence within the meaning of Art. 67 GG lies in the fact that the Federal Chancellor takes the initiative himself and not Parliament takes action against him. He can discipline the parliamentary majority that supports him with a vote of confidence or with a mere threat. If it is not answered in the affirmative, he can propose to the Federal President to dissolve the Bundestag.

The vote of confidence cannot be used arbitrarily to dissolve the Bundestag at a suitable point in time; rather, there must be a “real” government crisis. However , on the occasion of an organ complaint in 1983, the Federal Constitutional Court granted the Federal Chancellor and the Federal President a great deal of leeway in this matter. The Federal Constitutional Court confirmed this leeway in its decision on the dissolution of the Bundestag in 2005 .

Constitutional basis

Art. 68 GG in its version unchanged since May 23, 1949 reads:

- Article 68

- (1) If a request by the Federal Chancellor to express his confidence in him does not find the approval of the majority of the members of the Bundestag, the Federal President may dissolve the Bundestag within twenty-one days at the suggestion of the Federal Chancellor. ²The right to dissolution expires as soon as the Bundestag elects another Federal Chancellor with a majority of its members.

- (2) There must be forty-eight hours between the motion and the vote.

Voting type

For voting on the Federal Chancellor's vote of confidence, the type of voting is neither regulated in the Basic Law nor in the Rules of Procedure of the Bundestag (GOBT) . In contrast to the election of the chancellor and the vote on the vote of no confidence, both of which are secret according to the GOBT , the Bundestag has in practice created the customary right of roll-call voting , i.e. the clearest form of open voting, for questions of confidence . The juxtaposition of secret and name voting in one and the same elected office (Federal Chancellor) has been described as a remarkable "inconsistency" in the technical literature on constitutional law. This is also conspicuous since the vote of no confidence and the question of confidence appear in succession both in the Basic Law (Articles 67 and 68) and in the Bundestag's rules of procedure (Articles 97 and 98).

Emergence

The Weimar Constitution of 1919 (WRV) knew neither a question of confidence nor a constructive vote of no confidence . Rather, Art. 54 WRV contained the provision that the Reich Chancellor and the Reich Ministers "require the confidence of the Reichstag to carry out their office." They had to resign if the Reichstag withdrew their trust by an "express resolution". This so-called destructive vote of no confidence made it possible for the Reichstag to force the Reich Chancellor (or a Reich Minister) to give up his office , even if the parliamentary majority expressing the mistrust did not share a common policy. In contrast to the Bundestag, the Reichstag thus had an indirect say in the composition of the Reich government.

The problem with the system was that there could be purely negative majorities in parliament that overthrew a government but did not bring a new one into office. This became particularly virulent in 1932, when Reich Chancellors Franz von Papen and Kurt von Schleicher could not expect any support or tolerance from the parties. When the Reichstag met and demanded immediate resignation, the von Papen government had been overthrown in November, and von Schleicher had to fear the same when the Reichstag would meet again at the end of January 1933.

The provisions of Art. 67 and Art. 68 GG, i.e. the constructive vote of no confidence and the question of confidence, strengthen the position of the head of government and reduce the possibilities for politically opposed parliamentary groups to jointly remove an unpopular Chancellor from office. At the same time, the Basic Law also weakens the position of the Federal President in favor of the Federal Chancellor. Since the Federal Ministers only need the confidence of the Federal Chancellor to carry out their duties and neither the Federal President nor the Bundestag can replace them, the Federal Chancellor is the central political organ of action in the Federal Republic's political system .

In contrast to the Reich Chancellor, the Federal Chancellor has a massively strengthened position. Nevertheless, it remains tied to Parliament via the possibility of being voted out at any time by a newly formed parliamentary majority. The position of the Federal President is far weaker here than in Weimar times, since the Reich President could dismiss the Reich Chancellor and any of his ministers at any time without the consent of Parliament.

Linking the question of trust with a question of fact

The Federal Chancellor can combine the vote of confidence according to Article 81, Paragraph 1 of the Basic Law with a draft law or, like Gerhard Schröder 2001, with another application (vote on the military deployment of the Bundeswehr in Afghanistan ) or a simple parliamentary resolution.

This is not constitutionally necessary. Such a link still has two functions:

- Disciplinary function: The government can they reunite supportive parliamentary groups in an important property controversy behind by passing through such a package deal makes clear that it makes a certain kind position for essential core of their governance and will continue to carry out only as the government order.

- Process-related function: In accordance with the principles mentioned, the Chancellor can demonstrate to other constitutional bodies (Federal President and BVerfG) that he no longer finds parliamentary support in a key issue of his government policy and that he sees himself incapable of acting in accordance with this central government program.

Deadline

The stipulated time limit of 48 hours serves to enable each member of parliament to take part in this important vote and to give him the time to reassure himself of the scope of his decision. In this way, similar to the same period between the application and the vote, in the case of a constructive vote of no confidence, a Member should be prevented from letting his decision be influenced by situational, temporary emotions.

Legal consequences

With a positive answer to the vote of confidence, the Bundestag signals that it continues to have confidence in the Federal Chancellor. In this case, there are no legal consequences; any resolution presented in accordance with Art. 81 GG is accepted.

The Federal Chancellor has three options for any other answer to the question of confidence:

- After the negative answer to the confidence question, he is not forced to take any further steps. For example, he can try to continue working as the Federal Chancellor of a minority government . He can also try to form a new government with a viable majority by changing the coalition partner or adding another partner. He can also resign. Even if the last two options are of great constitutional relevance, they do not depend on a negative answer to the question of confidence, rather they are open to him at any time.

- The second option for the Federal Chancellor is to ask the Federal President to dissolve the Bundestag. In this case, the Federal President is given important political rights that he can only exercise in such exceptional situations. He has the option of either giving in to the Federal Chancellor's request or rejecting the request. The dissolution of the Bundestag must take place within twenty-one days. The Federal Chancellor's request can be withdrawn until the Federal President has made a decision. If the Bundestag has already elected a new Federal Chancellor, the dissolution of the Bundestag is not permitted.

- The third possibility that arises for the Federal Chancellor is to apply to the Federal President for a legislative emergency. In order to explain the legislative emergency, the Federal President depends on the approval of a fourth constitutional body, the Federal Council . An additional condition is that the Bundestag must not be dissolved.

In no case can the Federal Chancellor independently take a decision that encroaches on the powers of constitutional bodies other than the Federal Government .

Further formalities

The vote of confidence is constitutionally an instrument to which only the Federal Chancellor is entitled. Neither a Federal Minister nor the Deputy Federal Chancellor can ask the Federal Chancellor.

The request of the Bundestag to the Federal Chancellor to ask the vote of confidence is also not anchored in constitutional law. Such a request, as the SPD submitted to the Bundestag in 1966 after the fall of the Erhard government , but before Erhard's resignation, was not legally binding and thus constitutionally irrelevant. Erhard actually did not comply with this "request".

Political impact

The strong position of the Federal Chancellor in the political system of the Federal Republic is also linked with the fact that his downfall in fact requires a new coalition of education. This can be done on the one hand by cooperation of previous coalition members with (parts of) the opposition or by converting individual coalition members to the opposition, as was the prerequisite for the constructive vote of no confidence in 1972.

The Federal Chancellor can discipline political deviants in the coalition that supports him by asking the vote of confidence or even by threatening them (see Federal Chancellor Schmidt 1982 and Federal Chancellor Schröder 2001): Ultimately, he asks them the question of whether they are still all in all are willing to support his policy, or whether - if the Federal President decides in the interests of the Federal Chancellor - they want to be responsible for the at least temporary breach of the government and its majority. They have to ask themselves whether they have a chance of being re-elected if the Bundestag is threatened with a new election in the event of a negative answer to the vote of confidence, or whether the party members they have to re-nominate or the voters behave as "betrayal" of the government consider and pass them over. The possibility of your party losing government power in a new election must also be taken into account.

The question of confidence is particularly explosive when it is linked to a decision on the matter ( draft law or another proposal): Any deviants must weigh up whether they actually reject the overall policy of the Chancellor and want to trigger new elections or the declaration of a legislative emergency and thus the temporary disempowerment of the Bundestag or whether, in view of these alternatives, they are prepared to endorse something they regard as deserving of rejection.

In the run-up to the first actual connection between the question of confidence and a request for a matter in November 2001, journalists questioned whether this type of pressure exerted on MPs was (politically) permissible. In this way two decisions that are not directly related would be linked; it would create a dilemma for those MPs who wanted to give different answers to these questions. It was countered that at least the link between the question of confidence and a draft law is expressly provided for in the Basic Law and that a link with a proposal for a matter is then even more permissible; the pressure exerted on the deputies was wanted by the authors of the Basic Law.

history

| date | Federal Chancellor (party) | Yes | No | abstention | absent / invalid | % Yes-votes | Trust pronounced? |

episode |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20th September 1972 | Willy Brandt ( SPD ) | 233 | 248 | 1 | 14th | 47.0% | No | Dissolution of the Bundestag |

| 5th February 1982 | Helmut Schmidt (SPD) | 269 | 225 | 0 | 3 | 54.1% | Yes | |

| 17th December 1982 | Helmut Kohl ( CDU ) | 8th | 218 | 248 | 23 | 1.6% | No | Dissolution of the Bundestag |

| November 16, 2001 | Gerhard Schröder (SPD) | 336 | 326 | 0 | 4th | 50.5% | Yes | |

| July 1, 2005 | Gerhard Schröder (SPD) | 151 | 296 | 148 | 5 | 25.2% | No | Dissolution of the Bundestag |

1966: Request for a vote of confidence

The vote of confidence under Article 68 of the Basic Law came into the Bundestag for the first time in 1966 in an unusual way. After the coalition of CDU / CSU and FDP under Federal Chancellor Ludwig Erhard collapsed, the SPD put a “request for a vote of confidence” on the agenda, with the approval of the FDP in the council of elders. The “request” on November 8, 1966 was even accepted, with 255 votes to 246.

Chancellor Erhard was not obliged to actually ask the vote of confidence after the "request", which he also did not indignantly. But the SPD had achieved its goal: in the event of a constructive vote of no confidence, it would have had to form a government with the FDP and elect a specific candidate for chancellor. The SPD and FDP were not yet ready for this, also in view of their weak majority in the Bundestag. But the “request for a vote of confidence” clearly demonstrated that Erhard had finally lost the approval of the FDP and that no minority government of Erhard would tolerate it either. On December 1st, the grand coalition of CDU / CSU and SPD came about under Chancellor Kurt Georg Kiesinger .

This incident was followed by the discussion as to whether such a “request” was constitutional. Helmuth F. Liesegang affirmed this in Münch's commentary on the Basic Law, because parliamentary government control had priority, and the wording of the Basic Law did not rule out the possibility that the application did not come from the Chancellor's initiative. However, in the period that followed, a “request for a question of confidence” was never made again.

1972: Willy Brandt

In 1969 Willy Brandt became Federal Chancellor with an SPD-FDP coalition . In the dispute over the Eastern Treaty , MPs from the SPD and FDP had converted to the CDU / CSU opposition. In 1972, when the opposition believed they had enough support for a constructive vote of no confidence, they received two votes fewer than needed. On the other hand, the government did not have a majority for the budget. Since a self-dissolution of the Bundestag was and is not provided for under constitutional law, Brandt put the vote of confidence on September 20, 1972 .

In the vote on September 22, 1972, Brandt's confidence was not expressed. The members of the federal government did not take part in the vote, so the defeat was brought about deliberately, it was a "bogus vote of confidence". However, even if all members of the Bundestag had participated, the motion would not have found the necessary majority (249 votes). The situation corresponded exactly to that presented by the Federal Constitutional Court ten and a half years later: Brandt could no longer be sure of his majority. Before that, there had been a defeat in the adoption of the budget. The federal ministers' failure to take part in the vote of confidence was only to be understood as ensuring that the vote would be defeated. Just one day later, on September 22, 1972, Federal President Gustav Heinemann dissolved the Bundestag. The 1972 federal election on November 19 clearly confirmed Brandt's coalition of the SPD and FDP.

1982: Helmut Schmidt

After there was great tension over the federal budget in 1982 in the coalition of the SPD and FDP, which has ruled since 1969 , Federal Chancellor Helmut Schmidt decided on February 3, 1982 to put the vote of confidence. The discussion found its crystallization point in social policy, and discussions about the NATO double decision prevailed especially within the SPD parliamentary group .

In the vote on February 5, 1982, Schmidt received a positive vote of confidence from parliament. Nevertheless, the internal party disputes and the differences to the FDP intensified in the period that followed. Despite a cabinet reshuffle, the conflict over the federal budget in 1983 finally broke the coalition: on September 17, 1982, the federal ministers belonging to the FDP declared their resignation, on October 1, Federal Chancellor Schmidt was overthrown by a constructive vote of no confidence by the CDU / CSU and FDP, and Helmut Kohl elected Chancellor.

1982: Helmut Kohl

Helmut Kohl from the CDU had separated the FDP from its coalition with the SPD and was elected Chancellor on October 1, 1982 with the votes of the CDU / CSU and FDP. A new election of the Bundestag should give the new coalition its own legitimation by the voters. During the coalition negotiations with the FDP, Helmut Kohl had announced March 6, 1983 as the new election date.

Kohl could have resigned as Chancellor. In the subsequent election of Chancellor ( Art. 63 GG) by the Bundestag, the coalition parties could have counted on the fact that no Chancellor would have been elected with an absolute majority. Then the Federal President would have had the opportunity to dissolve the Bundestag. But this would have been unsafe; in addition, it makes more impression in the election campaign not only to be able to act as executive chancellor. Parliament voted on December 17, 1982 on the vote of confidence . Although the joint federal budget for 1983 had only been decided the day before, Parliament did not trust the Chancellor.

After heated discussions about the constitutionality of the process, the Federal President Karl Carstens decided on January 7, 1983 to order the dissolution of the Bundestag and to call for new elections for March 6, 1983. The Federal Constitutional Court, which was called upon in the course of this discussion, specified the above-mentioned principles in its decision, but decided against declaring the Federal President's order unconstitutional. Federal President Carstens had openly stated that he would resign if the Federal Constitutional Court should declare the dissolution of parliament to be unconstitutional. In the also controversial reasoning of the judgment, the judges of the Federal Constitutional Court stated that due to the agreement with the FDP about the bringing about of a new election, Chancellor Kohl could actually no longer count on the trust of the FDP members of the Bundestag and the behavior was therefore constitutional.

The Bundestag election of March 6, 1983 , was clearly won by the CDU / CSU, the FDP remained a coalition partner despite internal party disputes and heavy losses.

2001: Gerhard Schröder

After the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001 , Federal Chancellor Gerhard Schröder assured the United States of Germany's unlimited solidarity on the same day. Since, according to the USA, most of the training of the terrorists took place in Afghanistan , which is ruled by the Taliban , the UN Security Council demanded the extradition of the Al-Qaida terrorists and, after the Taliban failed to comply with this demand, authorized coercive military measures against the regime. These finally took place in November 2001 under the leadership of the USA and led to the overthrow of the Taliban. Since NATO had also established the case of an alliance , the Federal Republic should take part in this war with the Bundeswehr . According to a ruling by the Federal Constitutional Court in 1994 ("AWACS I"), any deployment of the Bundeswehr outside of NATO territory requires the approval of the Bundestag. Within the coalition of the SPD and Bündnis 90 / Die Grünen , some MPs announced that they would not give their consent. Although through the support of the CDU / CSU and FDP a wide parliamentary majority of the Bundestag would have been safe for use of armed forces, Chancellor Schröder decided on 16th November 2001 , the confidence of the Bundeswehr with the vote on the participation in the war in Afghanistan to connect (so-called connected motion of trust ). In his statement, he made it clear that, on the one hand, a broad parliamentary majority is important and is also perceived internationally, but he sees it as essential that he must rely on a majority of the coalition that supports him in such an essential political decision.

CDU / CSU and FDP refused to express their confidence in the Chancellor and therefore voted against the associated proposal. The majority of MPs from the SPD and Greens voted in favor of the motion. Eight Greens, who originally wanted to vote against the use of the Bundeswehr, split their votes into four yes and four no. They wanted to express the ambivalence of their vote: On the one hand, they supported the coalition's overall policy, on the other hand, they were against the deployment of the Federal Armed Forces. In addition, due to the absence of some CDU / CSU MPs, a simple majority would have been secured for the application anyway: If the eight MPs had rejected the federal government, they would not have prevented the Federal Armed Forces from being deployed. As a result of this division, the Federal Chancellor's motion received a total of 336 with 334 votes required and 326 against. The Federal Chancellor was thus justly trusted. A heated discussion developed within the party among the Greens, but it subsided relatively quickly.

In the run-up to this vote of confidence, the Scientific Service of the Bundestag dealt with the problem of the split majority: While an absolute majority of the members of the Bundestag is required to answer the vote of confidence positively , a simple majority is sufficient to accept a decision on the matter . So it could have happened that the Federal Chancellor refused to trust, but at the same time a factual decision was made in his favor. Bundestag President Thierse has apparently decided, in agreement with the scientific service of the German Bundestag, in favor of this different counting of the majority.

2005: Gerhard Schröder

After the last red-green coalition at state level was voted out on May 22, 2005 in the state elections in North Rhine-Westphalia in 2005 , Federal Chancellor Gerhard Schröder announced on the evening of the election that he would seek new elections. In order to achieve the premature dissolution of the Bundestag and early Bundestag elections in autumn 2005 , Schröder, like Helmut Kohl before, chose the way in 1982 via the vote of confidence. On June 27, 2005 , the Federal Chancellor submitted his motion to the Bundestag to express his confidence in him.

On July 1, 2005, the German Bundestag dealt with the Federal Chancellor's motion in its 185th session as item 21 on the agenda. In the debate, the Chancellor justified his motion with the inability of his government to act and the internal SPD conflict surrounding the 2010 reform agenda . He could no longer be sure of a “stable majority in the Bundestag”. Regarding the question of the constitutionality of his motion, the Chancellor referred in the debate to the vote of confidence that Helmut Kohl had put in 1982. In the roll-call vote that followed, the Federal Chancellor was not trusted. Of the 595 MPs who cast a valid vote, 151 voted “Yes”, 296 “No” and 148 abstained. The Federal Chancellor's motion thus failed to achieve the required majority of at least 301 yes-votes.

On July 13, 2005, the Federal Chancellor proposed to the Federal President that the Bundestag should be dissolved in accordance with Article 68 of the Basic Law. For this purpose, the Federal Chancellor sent the Federal President a dossier that proved his loss of confidence in the Bundestag. In this dossier, Federal Chancellor Schröder explained why, in his opinion, the 15th Bundestag should be dissolved by the Federal President at an early stage.

Federal President Horst Köhler dissolved the 15th German Bundestag on July 21, 2005 and ordered new elections for September 18, 2005. He justified his discretionary decision to dissolve the Bundestag by stating that Germany needed new elections in view of the major challenges the country was facing. He could not see that a different assessment of the situation is clearly preferable to that of the Federal Chancellor. The Chancellor had explained to him that he could no longer rely on the constant support of the Bundestag for his reform policy. Unlike Karl Carstens threatened to resign in a comparable situation in 1983, the Federal President would not resign if the Federal Constitutional Court should declare its decision to dissolve unconstitutional.

On August 1, 2005, the members of parliament Jelena Hoffmann (SPD) and Werner Schulz (Bündnis 90 / Die Grünen) initiated an organ dispute against the Federal President before the Federal Constitutional Court against the dissolution order . The applicants considered the vote of confidence put by Chancellor Schröder to be “unreal”, so that, in their opinion, the conditions for dissolving the Bundestag were not met. They feared the change to a chancellor democracy . On August 25, 2005, the Federal Constitutional Court announced its 7-1 vote on August 22, 2005, that the dissolution of the Bundestag was compatible with the Basic Law. The applications of some small parties , who particularly wanted to reduce the admission requirements, had already been rejected on August 8, 2005. However, the Federal Constitutional Court did not comment on the content, but rejected the applications aimed at a change in the admission modalities due to a lack of authorization to apply or due to a time limit.

See also: Judgment of the Federal Constitutional Court on the vote of confidence 2005

Germany: federal states

The vote of no confidence is anchored in almost all state constitutions, only Bavaria does not know it. In contrast, the question of trust is not so widespread as a formal instrument: Brandenburg , Hamburg , Hesse , Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania , Saarland , Saxony-Anhalt , Schleswig-Holstein and Thuringia have mentioned it in the constitutional text. What they all have in common is that the constitutional consequences on the part of the Prime Minister or the state government end as soon as the state parliament has elected a new government.

Brandenburg has a similar procedure to the Basic Law: The state parliament can dissolve itself within 20 days after the negative answer, after which the Prime Minister has another 20 days to dissolve.

For Hamburg, citizenship can dissolve itself within three months or can subsequently express its trust. If there is also no new election of a Senate, the Senate can for its part dissolve the citizenship within two weeks.

In Hesse, the government ends with a negative answer to the confidence question. The state parliament is dissolved after 12 days if there is no new election. The Hessian Prime Minister Roland Koch asked on September 12, 2000 in connection with the CDU donation affair. He received all 56 votes of his coalition of CDU and FDP in a roll-call, i.e. non-secret vote. A similar procedure as in Hesse also applies in Saarland; here the deadline is three months.

In Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania and Saxony-Anhalt the parliament can be dissolved by the state parliament president within two weeks after the negative answer to the question of confidence at the request of the prime minister, while in Schleswig-Holstein the prime minister can do this himself within ten days.

In Thuringia, the state parliament is automatically dissolved three weeks after the negative answer if no new elections have taken place by then.

2009 in Schleswig-Holstein: Peter Harry Carstensen

In July 2009, the Prime Minister of Schleswig-Holstein, Peter Harry Carstensen, put the vote of confidence in the state parliament on July 23. His aim was to bring about new elections at the same time as the general election by deliberately losing the vote of confidence . The Prime Minister cited the loss of trust in the coalition partner as the reason.

As expected, the vote of confidence was answered negatively with 37 of the 69 votes of the MPs, so that new elections for the Schleswig-Holstein state parliament could take place parallel to the federal election on September 27, 2009.

European states

A vote of no confidence to replace the government is common in almost all parliamentary systems; However, Cyprus as a presidential system does not know it.

A vote of confidence is not that common; often the effects of a negatively answered question of confidence are identical or similar to the effects of a successful vote of no confidence, for example in Denmark , Latvia , Poland , Portugal , Slovakia , Spain and the Czech Republic , where in both cases the government has to resign. Often there is no precise distinction between a vote of confidence and a vote of no confidence: There is only one common regulation, as in Austria , where the refusal of confidence also results in the resignation of the Federal Minister concerned or the entire Federal Government ( Art. 74 Federal Constitutional Law ), or in Sweden , where there is only one corresponding vote of no confidence.

Initial vote of confidence: It is also common for a newly formed government to put a vote of confidence in countries where it is appointed by the head of state and not by parliament, such as in Greece , Italy or Poland . In Bulgaria this applies in two respects: the constitution requires that the prime minister first submit to a vote of confidence in the National Assembly, after being sworn in he presents his cabinet and the ministers must also submit to a vote of confidence. If they fail - as happened in 2005 - the entire government is suspended and the President of the Republic has to give another party the mandate to form the government.

In Finland and Ireland , the government ends when there is a lack of confidence in parliament; According to the constitutional text, this does not necessarily have to be formally expressed. In this respect, this regulation appears similar to that of the Constitution of the Free State of Bavaria .

In Belgium there is a vote of confidence. If it is answered in the negative, parliament must elect a new head of government within three days. Otherwise the king can dissolve parliament. The vote of no confidence must either be constructive or the king can dissolve parliament.

In France , every government declaration is in fact a question of confidence. The head of government can combine the vote of confidence with a draft law. The vote of confidence and also the draft law are deemed to have been accepted if no motion of censure is submitted within the next 24 hours.

In Slovenia , the negative answer to the question of confidence is followed by either a new government election or the dissolution of parliament. The vote of no confidence is constructive.

Individual evidence

- ↑ So Schröder applies for a vote of confidence - parliamentary groups agreed on roll-call vote Die Welt of November 15, 2001, 2nd para.

- ↑ Hans Meyer , The position of parliaments in the constitutional order of the Basic Law , in: Hans-Peter Schneider , * Wolfgang Zeh (Ed.): Parliamentary Law and Parliamentary Practice in the Federal Republic of Germany: A Handbook, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1989, 1924 pp. 117-163 (122: footnote 30). ISBN 3-11-011077-6

- ↑ Rules of Procedure of the Bundestag on the vote of no confidence (Section 97) and the question of confidence (Section 98). ( Memento from March 5, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Stenographic Reports, 5th electoral term, 70th session, pp. 3302/3303.

- ↑ Helmuth CF Liesegang in the Basic Law Commentary by Münchs, Article 67, para. 8-9.

- ↑ Federal Law Gazette . Retrieved November 6, 2019 .

- ↑ BVerfGE 62, 1 resolution of the Bundestag I, judgment of the 2nd Senate of the Federal Constitutional Court of February 16, 1983

- ↑ BT-Drs. 15/5825 (PDF; 128 kB)

- ↑ Plenary minutes 15/185 (PDF; 388 kB)

- ↑ cf. Kiel State Parliament removes Carstensen's trust on zeit.de, July 23, 2009

literature

- General

- Klaus Stern : The constitutional law of the Federal Republic of Germany . tape 2 : State organs, state functions, financial and budgetary constitution, emergency constitution. Beck, Munich 1980, ISBN 3-406-07018-3 .

- Wolfgang Rudzio : The political system of the Federal Republic of Germany . 6th edition. UTB, Stuttgart 2003, ISBN 3-8252-1280-7 .

- Jürgen Plöhn: “Constructive vote of no confidence” and “question of trust” in an international comparison - a misconstruction of the German constitution? In: Jürgen Plöhn (Ed.): Sofia Perspectives on Germany and Europe. Studies in economics, politics, history, media and culture . Lit, Münster 2006, ISBN 3-8258-9498-3 , pp. 127–165 ( online in Google Book Search). (Political Science, 133).

- Sebastian Deißner: The questions of trust in the history of the FRG . VDM Verlag, Saarbrücken 2009, ISBN 978-3-639-19648-1 .

- Karlheinz Niclauß: Real and resolution-oriented question of trust. A replica. . in: Journal for Parliamentary Issues, Issue 3/2007, pp. 667–668

- 1972

- Wolfgang Zeh : Calendar of events on the way to dissolving the Bundestag on September 22, 1972 . In: Klemens Kremer (Ed.): Parliament Dissolution. Practice, theory, outlook . Heymann, Cologne, Berlin, Bonn, Munich 1974, ISBN 3-452-17787-4 , pp. 151-158 .

- Eckart Busch: The dissolution of parliament 1972. Constitutional historical and constitutional appraisal . In: Journal for Parliamentary Issues (ZParl) . Volume 4, No. 2 , 1973, ISSN 0340-1758 , pp. 213-246 .

- 1982

- Klaus Bohnsack: The coalition crisis in 1981/82 and the change of government in 1982 . In: ZParl . Volume 14, No. 1 , 1983, p. 5-32 .

- Wolfgang Heyde, Gotthard Wöhrmann: The dissolution and new election of the Bundestag in 1983 before the Federal Constitutional Court . C. F. Müller, Heidelberg 1984, ISBN 3-8114-8983-6 .

- 2001

- Michael F. Feldkamp : Chronicle of the vote of confidence by Federal Chancellor Gerhard Schröder in November 2001 . In: ZParl . Volume 33, No. 1 , 2002, p. 5-9 .

- 2005

- Robert Chr. Van Ooyen: vote of no confidence and dissolution of parliament. Test standard for the admissibility of "fake" questions of trust from a constitutional point of view; in: Recht und Politik, 3/2005, pp. 137–141.

- Wolf-Rüdiger Schenke , Peter Baumeister : Early elections, surprise coup without a constitutional breach? In: Neue Juristische Wochenschrift (NJW) . 2005, ISSN 0341-1915 , p. 1844-1846 .

- Michael F. Feldkamp : Chronicle of the Federal Chancellor's vote of confidence on July 1, 2005 and the dissolution of the German Bundestag on July 21, 2005 . In: ZParl . Volume 37, No. 1 , 2006, p. 19-28 .

- Roman Dickmann : The cutting of the historical-systematic rope of a constitutional norm - A critical consideration of the decision of the Federal Constitutional Court to dissolve the Bundestag in 2005 . In: Bayerische Verwaltungsblätter (BayVBl.) . N. F. Boorberg, 2006, ISSN 0522-5337 , p. 72-75 .

- Simon Apel, Christian Körber, Tim Wihl: The Decision of the German Federal Constitutional Court of 25 August 2005 Regarding the Dissolution of the National Parliament . In: German Law Journal (GLJ) . 2005, p. 1243-1254 .

- Sven Leunig: The premature termination of the Bundestag electoral term - prerogative of parliament or right of the Federal Chancellor? ", In: Journal for Parliamentary Questions, vol. 39 (2008), Issue 1, pp. 157-163.

- 2008

- Sven J. Podworny : The resolution-oriented vote of trust - with special consideration of the Federal Constitutional Court rulings of 1983 and 2005 . Carl Heymanns Verlag, Cologne 2008, ISBN 978-3-452-26832-7 .

- 2013

- Philipp Braitinger : The question of confidence according to Article 68 of the Basic Law - constitutional foundations, procedures and problems . Dr. Kovac Verlag, Hamburg 2013, ISBN 978-3-8300-7215-7 .

Web links

- Judgment of the Federal Constitutional Court on the question of confidence (BVerfG, 2 BvE 1/83 of February 16, 1983)

- bpb.de: Question of trust

- PDF file of the shorthand minutes of the debate on November 16, 2001 on the vote of confidence by Federal Chancellor Schröder (445 kB)

- PDF file of the shorthand minutes of the debate on July 1, 2005 on the vote of confidence by Federal Chancellor Schröder (334 kB)

- Decision of the Federal Constitutional Court of 25 August 2005 on a vote of confidence and new elections in 2005