Passenger pigeon

| Passenger pigeon | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Preparation of a male passenger pigeon |

||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||

|

||||||||||

| Scientific name of the genus | ||||||||||

| Ectopistes | ||||||||||

| Swainson , 1827 | ||||||||||

| Scientific name of the species | ||||||||||

| Ectopistes migratorius | ||||||||||

| ( Linnaeus , 1766) |

The passenger pigeon ( Ectopistes migratorius ) is a species of bird in the family of pigeons (Columbidae), the end of the 19th century in liberty eradicated was and the last in since the early 20th century, with the death of captive animal held as extinct applies.

At the beginning of the 19th century the pigeon was still one of the most common bird species with an estimated three to five billion specimens. It brooded in huge colonies , some of which were several hundred square kilometers in size, in eastern North America and ran through the country in swarms that are unimaginably large today . The fact that they are being eradicated is all the more dramatic. Alongside the bison , it became a symbol of the overexploitation of nature, which took place in North America especially in the 19th century. Although the extent of their persecution by humans is undoubtedly one of the main reasons for their extinction, the question of why the populations collapsed after a certain point in time and the surviving animals were no longer able to reproduce sufficiently has not been conclusively clarified.

The last wild bird was shot on March 24, 1900. The stuffed specimen is now in a museum in Columbus, Ohio . In 1914, Martha , the last animal of this species living in captivity, died .

Appearance

Ectopistes migratorius was a relatively large pigeon with a tail about 20 cm long, over two-thirds of the length towards the rear, wedge-shaped. The body length averaged 41 cm in males and 35 cm in females. The weight was between 255 and 340 g. The wings were pointed, the wing length was 20 cm. There was a sexual dimorphism . The beak was black, the eye was surrounded by a flesh-colored ring. Legs and feet were crimson. The type was the mourning dove not dissimilar, but larger, more colorful and long-tailed.

In the male, the head and upper side were bluish slate gray with dark, rounded and randomly distributed spots on the larger upper wing coverts and shoulder feathers. The iris was bright red. The color of the underside was orange to wine-red from the middle of the throat and tapered off towards the middle of the abdomen and the lower tail-coverts into whitish. The feathers on the sides of the neck varied from metallic violet to pink, golden or greenish on an orange to wine-red or bluish slate-colored background. The wings were blackish with pale borders. The central feathers were blackish, the rest whitish.

The female resembled the male, but was generally more dull in color, more brown on the top and more gray on the underside. The spotting of the shoulder feathers and upper wing-coverts was more pronounced, the iris orange to orange-red. The young woman's dress was similar to that of the female, but it was even more brownish-gray and looked scaly on the chest, neck and front back with light-colored hems. The wings of the hand were lined with reddish color, the shoulder feathers and upper wing-coverts were spotted even more strongly than in the female. The iris was brown.

distribution

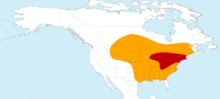

The passenger pigeon was found in North America east of the Rocky Mountains . The northern limit of the brood distribution extended through the south of the Canadian provinces of Saskatchewan and Manitoba , northern Ontario and central Québec to New Brunswick . In the United States, the western border ran from central Montana through South Dakota , central Nebraska , Kansas , Oklahomas and Texas to the Gulf of Mexico . In Florida , the area only extended to the north. However, the main breeding occurrence was concentrated in the area of the eastern deciduous forest zone, i.e. in the vicinity of the Great Lakes , in southern Ontario and north of the Appalachians . There were huge colonies mainly in the states of Wisconsin , Michigan , Minnesota , Ohio , Pennsylvania , New York and Massachusetts as well as in Ontario. Occasionally, colonies of migrating pigeons were found as far as Missouri and Oklahoma. In the rest of the area the species only nested in single pairs or small groups.

hikes

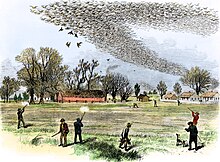

The passenger pigeon formed large flocks of hundreds or thousands of individuals, especially on the move. On various occasions these flocked to form even larger swarms, so that contemporary sources speak of train movements that darkened the sky and lasted for days. In other years the procession was evidently sparse and in smaller groups. The large swarms moved partly in a broad front, partly in kilometer-long, narrow rows. The density was also very different.

The migratory behavior of the species can be described as nomadic. Although it overwintered in the south, brooded in the middle of the range, and often dismigrated northwards after the breeding season , there were probably no fixed migration patterns. Colonies formed preferentially at locations where after years of fattening there was a rich supply of nut fruits. If there was no such offer in the following year, the location was abandoned. Nevertheless, there were colonies that lasted for several years. The large swarms that formed outside of the breeding season were guided in their migration behavior according to food availability or weather conditions. Snow storms or a thick blanket of snow could cause large movements of trains to the south. Under favorable conditions, however, the swarms stayed far to the north. It is assumed that a kind of loop train took place on the train going south , which led through the states on the Atlantic coast in autumn, but ran more west of the Appalachians in spring.

The appearance of large flocks was relatively unpredictable, but was often announced by the arrival of individual birds or smaller groups. In the spring, after the snow melted, the influx into the breeding areas began around February, but could drag on until April. On the other hand, the dismigrations began after the breeding season in some cases from mid-May. Autumn hikes started in August and often peaked in September.

The passenger pigeon only migrated during the day and mostly along scenic features such as coastlines and shorelines or mountain ranges. The height of the pull was very different. There are reports of very high flocks, but also of occasions when the birds let themselves be beaten out of the air from a height of 1 m with rods or clubs. The train speed was quite high and was probably around 100 km / h.

nutrition

The passenger pigeon specialized in nut fruits , which formed an abundant supply of food in the fattening years and offered the possibility of supplying the huge breeding colonies. These were primarily beechnuts , acorns of all American oak species and the nuts of the American chestnut . In summer berries and fruit were the main food. This included blueberries in particular , but also grapes, cherries, mulberries , pokeweed and the fruits of various types of dogwood . The food was mostly vegetable. Earthworms and caterpillars were also used as nestling food . Grain was also part of the diet.

The food was often eaten in huge schools. The nuts were picked up from the ground with their beak digging in the chaff or plucked from the trees. The movement of the noisy flocks is described as “rolling”, as the birds at the rear kept flying over the center of the flock and the treetops to forward positions. With a goiter that could reach the size of an orange when full, a relatively large throat and a large, powerful gizzard with which the nut fruits could be digested whole, the species was well adapted to its main diet. After eating, the birds often sat long in the trees to digest.

Reproduction

The passenger pigeon breeds mainly in huge colonies of mostly several hundred thousand pairs, but occasionally also in smaller groups or in single breeding pairs. Mating, nest building and incubation usually took place very synchronously. The breeding season began in April. After returning from the winter quarters at the end of winter, it could therefore take some time for the birds to brood. There was only one annual brood.

The size of the colonies ranged from 50 hectares to several thousand hectares. One of the largest colonies - it was located in Michigan in 1878 - stretched for 48–64 km in length and was between 5 and 10 km wide. It covered an area between 546 and 676 km². The largest colony ever established from 1871 was about 2216 km². It covered the southern two-thirds of Wisconsin and - together with a few other colonies in neighboring Minnesota - probably the entire population at that time.

The occupation of a colony is described by a contemporary as a deafening spectacle in which mating couples were found everywhere in the trees. After about three days the noise subsided and all the birds were building their nests.

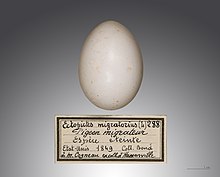

The nests were mostly between 4 and 20 m high in the trees, which were often densely populated. Often there were more than 50 nests in a tree; 317 nests were counted in a very large hemlock . The nest did not differ much from that of other pigeons and was a relatively flat structure made of twigs, about 15 cm in diameter and 6 cm in height. The construction time was between two and four days. The clutch consisted of a rounded, elliptical, white egg with a slight sheen, the dimensions of which averaged 37.5 × 26.5 mm. It was laid one day after the nest was completed and incubated for about 13 days.

The breeding behavior did not differ significantly from that of other pigeons. Both sexes took part in the incubation and rearing of young. At the beginning, the boys were fed goiter milk until they had built up fat reserves and their body weight exceeded that of their parents. The adult birds left the colony after 13 to 15 days of nestling. The cubs stayed in the nest for another day and then flew out. After 3–4 more days, they fledged and looked for nuts on the forest floor. About a week after fledging, they had broken down their initially extensive fat reserves.

Inventory development

Population decline and extinction

The passenger pigeon was still the most common bird in North America at the beginning of the 19th century and one of the most common bird species worldwide. Descriptions of the huge swarms sound almost implausible today. However, since they come from many independent sources and largely agree, they cannot be dismissed out of hand. Attempts to extrapolate the size of the passing flocks based on time measurements, speed estimates and the number of birds on an area have been made by Alexander Wilson (1812) and John James Audubon (1813, published 1832). The former had over two billion birds, the latter over a billion birds. In 1866, a swarm that passed through for over 14 hours was estimated at over three billion individuals.

Based on these figures, the rapid population collapse in the second half of the 19th century and the extinction of the species in the early 20th century appear particularly dramatic and remain at least partially a mystery. Already in the 17th and 18th centuries the species was severely decimated by hunting in the area of the Atlantic coast. In the Midwest and in the Great Lakes area, however, populations remained relatively stable until the middle of the 19th century. Only then did a rapid decline in stocks follow. In 1871 almost the entire remaining population was breeding in Wisconsin, which with an estimated 135 million birds made up only a tenth of the estimated population by the middle of the century. In the following decade the population was further decimated. In 1878 around 10 million birds were killed in one colony. By the 1880s there were only colonies of tens of thousands of birds. The pursuit continued, however, the breeding success failed, so that the last large swarm was observed in 1888. From 1889 onwards, the population only amounted to thousands of birds and by the early 1890s flocks of several hundred individuals had become rare. From 1895 the observation of ten birds was a specialty and from 1900 there were only a few, partly unconfirmed individual observations.

Without a doubt, the species' extinction is due to persecution by humans. However, in addition to excessive hunting, the likely cause of the collapse of the population is the interaction of several factors such as habitat destruction and disturbances in the breeding colonies. The question also remains why, after a certain point in time, the decimated populations were no longer able to reproduce to a sufficient extent. There are several hypotheses on this. One says that the species as colony breeder only offered the strategy of saturating potential predators with a constant surplus. Single breeding pairs or small groups only had insufficient adaptations to achieve the breeding success necessary for the conservation of the species. They continued to breed relatively openly in poorly hidden nests. In addition, the clutch consisted of only one egg. According to another theory the species was no longer able to find breeding sites with the necessary range of fattening crops as the swarms decreased in size and thus became less scattered. However, this assumption is questionable, since single breeding pairs or smaller colonies would have been less dependent on such an oversupply. Other assumed causes such as climate changes, weather influences or diseases cannot be adequately proven.

Persecution by man

The passenger pigeon has been hunted excessively for human consumption . In 1855 a dealer sold 18,000 pieces in a single day. The bird painter John James Audubon (1785-1851) described the massive killings when hunting the animals:

“The banks of the Ohio were teeming with men and boys, shooting non-stop at the pilgrims who were flying lower as they crossed the river. Many were destroyed in this way. For a week or more, the population did not eat any meat other than that of the pigeons. During this time, the atmosphere was saturated with the peculiar smell that this species gives off. […] Before sunset there were few pigeons to be seen, but a lot of people with horses and wagons, rifles and ammunition had already set up camp on the edge of the forest. Two farmers from the vicinity of Russellsville, over a hundred miles away, had brought over three hundred pigs to be fattened with the pigeons to be slaughtered. Here and there one saw people plucking and salting in the midst of large piles of pigeons that had already been shot. (quoted in Albus, p. 12 f.) "

The tender and very fatty meat of the nestlings was particularly popular . The North American Indians used pigeon fat as a substitute for butter and bacon. The American settlers viewed the animals as crop pests , either because of their preferred food - they lived, among other things, from the overproduction of seeds in the prairie grass and could also have devastated the grain fields - or because of their droppings. The hunt for birds became more professional with technical progress. Messages about the bird's nesting sites were transmitted via telegraph and a variety of hunting methods were used. Often they felled the trees in which there were hundreds of nests with young ones. The captured birds were using the railway transported.

Even after the total collapse in the 1880s, the species was persistently pursued and hunted. Attempts to breed the pigeons in captivity were unsuccessful. The last known passenger pigeon named " Martha " died on September 1, 1914 at the age of 29 in the Cincinnati Zoo . Your stuffed hide is kept at the Smithsonian Institution .

Today there are more than 1000 bellows and stand preparations worldwide, more than 50 in Germany alone (including in Augsburg , Berlin , Bonn , Greifswald , Halberstadt , Hamburg , Leipzig , Munich , Oldenburg , Stuttgart , Wiesbaden ). The pigeon is probably the most common species in museums around the world, and it was extinct in historical times.

See also

literature

- David E. Blockstein: Passenger Pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius) in The Birds of North America Online (A. Poole, Ed.), Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca 2002

- Anita Albus : From rare birds , S. Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2005, ISBN 3-10-000620-8

- FH Münster , students at the Münster School of Design : On the Disappearance of Animals , Jaja Verlag Berlin 2018, pp. 207–215, ISBN 978-3-946642-30-5 .

Web links

- Ectopistes migratorius in the endangered Red List species the IUCN 2008. Posted by: BirdLife International, 2008. Accessed on December 31 of 2008.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Blockstein (2002), section Breeding / Nest Site , see literature

- ↑ a b c Blockstein (2002), sections “Distinguishing Characteristics” and “Appearance”, see literature

- ↑ Blockstein (2002), section “Distribution”, see literature

- ↑ a b c d Blockstein (2002), section “Migration”, see literature

- ↑ a b Blockstein (2002), section “Food Habits”, see literature

- ↑ a b c d e Blockstein (2002), section “Breeding”, see literature

- ↑ Blockstein (2002), section Demography and Populations / Population Status , see literature

- ↑ Blockstein (2002), section “Conservation”, see literature

- ↑ Dieter Luther: The extinct birds of the world. The New Brehm Library / A. Ziemsen Verlag Wittenberg, 3rd updated edition 1986, pp. 92-94.