History of Ireland: Difference between revisions

This is a misleading statement and without modification is simply bad history. The issues where not about religion - but land ownership and economics. |

remove infobox better placed in RoI history article; trying to fix bollixed formatting |

||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

In 1922, after the [[Irish War of Independence]], the southern twenty-six counties of Ireland seceded from the United Kingdom (UK) to become the independent [[Irish Free State]] — and after 1948, the [[Republic of Ireland]]. The remaining six north eastern counties, known as [[Northern Ireland]], remained part of the UK. The [[history of Northern Ireland]] has been dominated by sporadic sectarian conflict between (mainly [[Roman Catholic|Catholic]]) [[Irish Nationalism|Nationalist]]s and (mainly [[Protestant]]) [[Unionism (Ireland)|Unionists]]. This conflict erupted into [[the Troubles]] in the late 1960s, until an [[Belfast Agreement|uneasy peace]] thirty years later. |

In 1922, after the [[Irish War of Independence]], the southern twenty-six counties of Ireland seceded from the United Kingdom (UK) to become the independent [[Irish Free State]] — and after 1948, the [[Republic of Ireland]]. The remaining six north eastern counties, known as [[Northern Ireland]], remained part of the UK. The [[history of Northern Ireland]] has been dominated by sporadic sectarian conflict between (mainly [[Roman Catholic|Catholic]]) [[Irish Nationalism|Nationalist]]s and (mainly [[Protestant]]) [[Unionism (Ireland)|Unionists]]. This conflict erupted into [[the Troubles]] in the late 1960s, until an [[Belfast Agreement|uneasy peace]] thirty years later. |

||

{{Life in the Republic of Ireland}} |

|||

==Early history: 8000 BC–AD 400== |

==Early history: 8000 BC–AD 400== |

||

Revision as of 23:51, 9 October 2007

| History of Ireland |

|---|

|

|

|

The History of Ireland began with the first known human settlement in Ireland around 8000 BC, when hunter-gatherers arrived from Britain and continental Europe, probably via a land bridge.[1] Few archaeological traces remain of this group, but their descendants and later Neolithic arrivals, particularly from the Iberian Peninsula, were responsible for major Neolithic sites such as Newgrange.[2][3] Following the arrival of Saint Patrick and other Christian missionaries in the early to mid-5th century, Christianity subsumed the indigenous pagan religion by the year 600.

From around 800, more than a century of Viking invasions wrought havoc upon the monastic culture and on the island's various regional dynasties, yet both of these institutions proved strong enough to survive and assimilate the invaders. The coming of Anglo-Norman mercenaries under Richard de Clare, 2nd Earl of Pembroke, nicknamed Strongbow, in 1169 marked the beginning of more than 800 years of direct English involvement in Ireland. The English crown did not begin asserting full control of the island until after the English Reformation, when questions over the loyalty of Irish vassals provided the initial impetus for a series of military campaigns between 1534 and 1691. This period was also marked by an official English policy of plantation which led to the arrival of thousands of English and Scottish Protestant settlers. From this period on, sectarian conflict became a recurrent theme in Irish history.

Throughout this period, Ireland regained a form of self-governing status through the Parliament of Ireland, but power was limited to the Anglo-Irish, Anglican minority while the majority Roman Catholic population suffered severe political and economic privations. In 1801, this parliament was abolished and Ireland became an integral part of a new United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland under the Act of Union.

In 1922, after the Irish War of Independence, the southern twenty-six counties of Ireland seceded from the United Kingdom (UK) to become the independent Irish Free State — and after 1948, the Republic of Ireland. The remaining six north eastern counties, known as Northern Ireland, remained part of the UK. The history of Northern Ireland has been dominated by sporadic sectarian conflict between (mainly Catholic) Nationalists and (mainly Protestant) Unionists. This conflict erupted into the Troubles in the late 1960s, until an uneasy peace thirty years later.

Early history: 8000 BC–AD 400

What little is known of pre-Christian Ireland comes from a few references in Roman writings, Irish poetry and myth, and archaeology. The earliest inhabitants of Ireland, people of a mid-Stone Age, or Mesolithic, culture, arrived sometime after 8000 BC, when the climate had become more hospitable following the retreat of the polar icecaps. About 4000 BC agriculture was introduced from the continent, leading to the establishment of a high Neolithic culture, characterized by the appearance of pottery, polished stone tools, rectangular wooden houses and communal megalithic tombs, some of which are huge stone monuments like the Passage Tombs of Newgrange, Knowth and Dowth, many of them astronomically aligned (most notably, Newgrange). Four main types of megalithic tomb have been identified: Portal Tombs, Court Tombs, Passage Tombs and Wedge Tombs. In Leinster and Munster individual adult males were buried in small stone structures, called cists, under earthen mounds and were accompanied by distinctive decorated pottery. This culture apparently prospered, and the island became more densely populated. Towards the end of the Neolithic new types of monuments developed, such as circular embanked enclosures and timber, stone and post and pit circles.

The Bronze Age properly began once copper was alloyed with tin to produce true bronze artifacts, this took place around 2000 BC, when some Ballybeg flat axes and associated metalwork was produced. The period preceding this, in which Lough Ravel and most Ballybeg axes were produced, and is known as the Copper Age or Chalcolithic, commenced about 2500 BC. This period also saw the production of elaborate gold and bronze ornaments, weapons and tools. There was a movement away from the construction of communal megalithic tombs to the burial of the dead in small stone cists or simple pits, which could be situated in cemeteries or in circular earth or stone built burial mounds known respectively as barrows and cairns. As the period progressed inhumation burial gave way to cremation and by the Middle Bronze Age cremations were often placed beneath large burial urns.

The Iron Age in Ireland began about 600 BC. By the historic period (AD 431 onwards) the main over-kingdoms of In Tuisceart, Airgialla, Ulaid, Mide, Laigin, Mumhain, Cóiced Ol nEchmacht began to emerge (see Kingdoms of ancient Ireland). Within these kingdoms a rich culture flourished. The society of these kingdoms was dominated by an upper class, consisting of aristocratic warriors and learned people, possibly including druids.

Historians developed the concept from the 17th century onwards that the language spoken by these people could be called the Goidelic languages, a branch of the Celtic languages, and this was explained as a result of invasions of Celts. However, research during the 20th century indicated otherwise, and in the later years of the century the conclusion drawn was that culture developed gradually and continuously, and that the introduction of Celtic language and elements of Celtic culture was a result of cultural exchange with Celtic groups on southwest continental Europe from the neolithic to the Bronze Age.[1][2] Little archaeological evidence was found for large intrusive groups of Celtic immigrants in Ireland. The hypothesis that the native Late Bronze Age inhabitants gradually absorbed Celtic influences has since been supported by some recent genetic research.[4]

The Romans referred to Ireland as Hibernia. Ptolemy in AD 100 records Ireland's geography and tribes. Ireland was never formally a part of the Roman Empire but Roman influence was often projected well beyond formal borders. Tacitus writes that an exiled Irish prince was with Agricola in Britain and would return to seize power in Ireland. Juvenal tells us that Roman "arms had been taken beyond the shores of Ireland". In recent years, some experts have hypothesized that Roman-sponsored Gaelic forces (or perhaps even Roman regulars) mounted some kind of invasion around 100,[5] but the exact relationship between Rome and the dynasties and peoples of Hibernia remains unclear.

Early Christian Ireland 400–800

The middle centuries of the first millennium AD marked great changes in Ireland.

Niall Noigiallach (died c.450/455) laid the basis for the Uí Néill dynasty's hegemony over much of western, northern and central Ireland. Politically, the former emphasis on tribal affiliation had been replaced by the 700s by that of patrilineal and dynastic background. Many formerly powerful kingdoms and peoples disappeared. Irish pirates struck all over the coast of western Britain in the same way that the Vikings would later attack Ireland. Some of these founded entirely new kingdoms in Pictland, Wales and Cornwall. The Attacotti of south Leinster may even have served in the Roman military in the mid-to-late 300s.[6]

Perhaps it was some of the latter returning home as rich mercenaries, merchants, or slaves stolen from Britain or Gaul, that first brought the Christian faith to Ireland. Some early sources claim that there were missionaries active in southern Ireland long before St. Patrick. Whatever the route, and there were probably many, this new faith was to have the most profound effect on the Irish.

Tradition maintains that in AD 432, St. Patrick arrived on the island and, in the years that followed, worked to convert the Irish to Christianity. On the other hand, according to Prosper of Aquitaine, a contemporary chronicler, Palladius was sent to Ireland by the Pope in 431 as "first Bishop to the Irish believing in Christ", which demonstrates that there were already Christians living in Ireland. Palladius seems to have worked purely as Bishop to Irish Christians in the Leinster and Meath kingdoms, while Patrick — who may have arrived as late as 461 — worked first and foremost as a missionary to the Pagan Irish, converting in the more remote kingdoms located in Ulster and Connacht.

Patrick is traditionally credited with preserving the tribal and social patterns of the Irish, codifying their laws and changing only those that conflicted with Christian practices. He is also credited with introducing the Roman alphabet, which enabled Irish monks to preserve parts of the extensive Celtic oral literature. The historicity of these claims remains the subject of debate and there is no direct evidence linking Patrick with any of these accomplishments. The myth of Patrick, as scholars refer to it, was developed in the centuries after his death. [7] There were Christians in Ireland long before Patrick came, and pagans long after he died.

The druid tradition collapsed, first in the face of the spread of the new faith, and ultimately in the aftermath of famine and plagues due to the climate changes of 535–536. Irish scholars excelled in the study of Latin learning and Christian theology in the monasteries that flourished shortly thereafter. Missionaries from Ireland to England and Continental Europe spread news of the flowering of learning, and scholars from other nations came to Irish monasteries. The excellence and isolation of these monasteries helped preserve Latin learning during the Early Middle Ages. The arts of manuscript illumination, metalworking, and sculpture flourished and produced such treasures as the Book of Kells, ornate jewellery, and the many carved stone crosses that dot the island. Sites dating to this period include clochans, ringforts and promontory forts.

The first English involvement in Ireland took place in this period. In 684 AD an English expeditionary force sent by Northumbrian King Ecgfrith invaded Ireland in the summer of that year. The English forces managed to seize a number of captives and booty, but they apparently did not stay in Ireland for long. The next English involvement in Ireland would take place a little more than half a millennium later in 1169 AD when the Normans invaded the country.

Early medieval era 800–1166

Main article Early Medieval Ireland 800–1166

The first recorded Viking raid in Irish history occurred in 795 when Vikings from Norway looted the island of Lambay, located off the Dublin coast. Early Viking raids were generally small in scale and quick. These early raids interrupted the golden age of Christian Irish culture starting the beginning of two hundred years of intermittent warfare, with waves of Viking raiders plundering monasteries and towns throughout Ireland. Most of the early raiders came from the fjords of western Norway.

By the early 840s, the Vikings began to establish settlements along the Irish coasts and to spend the winter months there. Vikings founded settlements in Limerick, Waterford, Wexford, Cork, Arklow and most famously, Dublin. Written accounts from this time (early to mid 840s) show that the Vikings were moving further inland to attack (often using rivers such as the Shannon) and then retreating to their coastal headquarters.

In 852, the Vikings Ivar Beinlaus and Olaf the White landed in Dublin Bay and established a fortress, on which the city of Dublin (from the Irish Gaelic An Dubh Linn meaning "the black pool") now stands. Olaf was the son of a Norwegian king and made himself the king of Dublin. After several generations a group of mixed Irish and Norse ethnic background arose (the so-called Gall-Gaels, Gall then being the Irish word for "foreigners" — the Norse). The descendants of Ivar Beinlaus established a long dynasty based in Dublin, and from this base succeeded in briefly dominating large parts of central and eastern Ireland.

However, the Vikings never achieved total domination of Ireland, often fighting for and against various Irish kings, such as Flann Sinna, Cerball mac Dúnlainge and Niall Glúndub. They were suborned by King Máel Sechnaill mac Domnaill of Meath at the battle of Tara in 980, but later staged another more significant battle when overseas Vikings landed at Dublin and were confronted by combined Irish forces led by Brian Boru. This was in 1014 and the Battle of Clontarf essentially ended Viking power in Ireland.[8] However the towns that the Vikings had founded continued to flourish and trade became an important part of the Irish economy.

Early Ireland had an unusual government. Ireland was divided into many small kingdoms called tuaths. Each tuath's king was elected by all the free men on its territory. The tuath was thus a body of persons voluntarily united and its territorial dimension was the sum total of the landed properties of its members. About 80 to 100 tuatha coexisted at any time throughout Ireland.Template:Inote Above the tuaithe were larger provincial kingdoms.

Later medieval Ireland

The coming of the Normans 1167–1185

By the 12th century, Ireland was divided politically into a shifting hierarchy of petty kingdoms and over-kingdoms. Power was exercised by the heads of a few regional dynasties vying against each other for supremacy over the whole island. One of these, the King of Leinster Diarmait Mac Murchada (anglicised as Diarmuid MacMorrough) was forcibly exiled from his kingdom by the new High King, Ruaidri mac Tairrdelbach Ua Conchobair. Fleeing to Aquitaine, Diarmait obtained permission from Henry II to use the Norman forces to regain his kingdom. The first Norman knight landed in Ireland in 1167, followed by the main forces of Normans, Welsh and Flemings in Wexford in 1169. Within a short time Leinster was regained, Waterford and Dublin were under the control of Diarmait, who named his son-in-law, Richard de Clare, heir to his kingdom. This caused consternation to King Henry II of England, who feared the establishment of a rival Norman state in Ireland. Accordingly, he resolved to establish his authority.

With the authority of the papal bull Laudabiliter from Adrian IV, Henry landed with a large fleet at Waterford in 1171, becoming the first King of England to set foot on Irish soil. Henry awarded his Irish territories to his younger son John with the title Dominus Hiberniae ("Lord of Ireland"). When John unexpectedly succeeded his brother as King John, the "Lordship of Ireland" fell directly under the English Crown.

|

|

The Lordship of Ireland 1185–1254

Initially the Normans controlled the entire east coast, from Waterford up to eastern Ulster and penetrated as far west as Galway, Kerry and Mayo. The most powerful lords in the land were the great Hiberno-Norman Lord of Leinster from 1171, Earl of Meath from 1172, Earl of Ulster from 1205, Earl of Connaught from 1236, Earl of Kildare from 1316, the Earl of Ormonde from 1328 and the Earl of Desmond from 1329 who controlled vast territories, known as Liberties which functioned as self-administered jurisdictions with the Lordship of Ireland owing feudal fealty to the King in London. The first Lord of Ireland was King John, who visited Ireland in 1185 and 1210 and helped consolidate the Norman controlled areas, while at the same time ensuring that the many Irish kings swore fealty to him.

Throughout the thirteenth century the policy of the English Kings was to weaken the power of the Norman Lords in Ireland. For example King John encouraged Hugh de Lacy to destabilise and then overthrow John de Courcy as Lord of Ulster, before creating him Earl of Ulster. Subsequently in 1210 John invaded Meath and Ulster and took control of the lands of both Earls. In 1241 the Earl of Meath, Walter de Lacy, died without a male heir and Meath was partitioned between his two granddaughters. Then in 1245 with the death of the last Lord of Leinster, Anselm Marshall, Leinster was partitioned between his five sisters and divided into the five counties of Kildare, Laois, Carlow, Kilkenny and Wexford. The partition of the original Lordships and the inheritance of lands by the often absentee husbands of Irish heiresses contributed to the military weakening of the Anglo-Normans.

The Hiberno-Norman community suffered from a series of events that ceased the spread of their settlement and power. Politics and events in Gaelic Ireland served to draw the settlers deeper into the orbit of the Irish.

Gaelic resurgence, Norman decline 1254–1360

By 1261 the weakening of the Anglo-Normans had become manifest when Fineen Mac Carthy defeated a Norman army at the Battle of Callann, Co. Kerry and killed John fitz Thomas, Lord of Desmond, his son Maurice fitz John and eight other Barons. In 1315, Edward Bruce of Scotland invaded Ireland, gaining the support of many Gaelic lords against the English. Although Bruce was eventually defeated at the Battle of Faughart, the war caused a great deal of destruction, especially around Dublin. In this chaotic situation, local Irish lords won back large amounts of land that their families had lost since the conquest and held them after the war was over.

The Black Death arrived in Ireland in 1348. Because most of the English and Norman inhabitants of Ireland lived in towns and villages, the plague hit them far harder than it did the native Irish, who lived in more dispersed rural settlements. After it had passed, Gaelic Irish language and customs came to dominate the country again. The English-controlled area shrunk back to the Pale, a fortified area around Dublin that ran through the counties of Louth, Meath, Kildare and Wicklow and the Earldoms of Kildare, Ormonde and Desmond.

Outside the Pale, the Hiberno-Norman lords adopted the Irish language and customs, becoming known as the Old English, and in the words of a contemporary English commentator, became "more Irish than the Irish themselves." Over the following centuries they sided with the indigenous Irish in political and military conflicts with England and generally stayed Catholic after the Reformation. The authorities in the Pale grew so worried about the "Gaelicisation" of Ireland that they passed special legislation in a parliament in Kilkenny (known as the Statutes of Kilkenny) banning those of English descent from speaking the Irish language, wearing Irish clothes or inter-marrying with the Irish. Since the government in Dublin had little real authority, however, the Statutes did not have much effect.

By the end of the 15th century, central English authority in Ireland had all but disappeared. England's attentions were diverted by its Wars of the Roses (civil war). The Lordship of Ireland lay in the hands of the powerful Fitzgerald Earl of Kildare, who dominated the country by means of military force and alliances with lords and clans around Ireland. Around the country, local Gaelic and Gaelicised lords expanded their powers at the expense of the English government in Dublin but the power of the Dublin government was seriously curtailed by the introduction of Poynings Law in 1494. According to this act the Irish parliament was essentially put under the control of the Westminster parliament.

Reformation (1536–1654) and Protestant Ascendancy (1654–1801)

Main article Early Modern Ireland 1536-1691

The Reformation, before which, in 1532, Henry VIII broke with Papal authority, fundamentally changed Ireland. While Henry VIII broke English Catholicism from Rome, his son Edward VI moved further, breaking with Papal doctrine completely. While the English, the Welsh and, later, the Scots accepted Protestantism, the Irish remained Catholic. This influenced their relationship with England for the next four hundred years, as the Reformation coincided with a determined effort on behalf of the English to re-conquer and colonise Ireland. This sectarian difference meant that the native Irish and the (Roman Catholic) Old English were excluded from political power.

Re-conquest and rebellion

See also Tudor re-conquest of Ireland.

From 1536, Henry VIII decided to re-conquer Ireland and bring it under crown control. The Fitzgerald dynasty of Kildare, who had become the effective rulers of Ireland in the 15th century, had become very unreliable allies of the Tudor monarchs. They had invited Burgundian troops into Dublin to crown the Yorkist pretender, Lambert Simnel as King of England in 1487. Again in 1536, Silken Thomas Fitzgerald went into open rebellion against the crown. Having put down this rebellion, Henry VIII resolved to bring Ireland under English government control so the island would not become a base for future rebellions or foreign invasions of England. In 1541, Henry upgraded Ireland from a lordship to a full Kingdom. Henry was proclaimed King of Ireland at a meeting of the Irish Parliament that year. This was the first meeting of the Irish Parliament to be attended by the Gaelic Irish chieftains as well as the Hiberno-Norman aristocracy. With the institutions of government in place, the next step was to extend the control of the English Kingdom of Ireland over all of its claimed territory. This took nearly a century, with various English administrations in the process either negotiating or fighting with the independent Irish and Old English lords.

The re-conquest was completed during the reigns of Elizabeth and James I, after several bloody conflicts. (See the Desmond Rebellions (1569–1573 and 1579–1583 and the Nine Years War 1594–1603, for details). After this point, the English authorities in Dublin established real control over Ireland for the first time, bringing a centralised government to the entire island, and successfully disarmed the native lordships. However, the English were not successful in converting the Catholic Irish to the Protestant religion and the brutal methods used by crown authority to pacify the country heightened resentment of English rule.

From the mid-16th and into the early 17th century, crown governments carried out a policy of colonisation known as Plantations. Scottish and English Protestants were sent as colonists to the provinces of Munster, Ulster and the counties of Laois and Offaly (see also Plantations of Ireland). These settlers, who had a British and Protestant identity, would form the ruling class of future British administrations in Ireland. A series of Penal Laws discriminated against all faiths other than the established (Anglican) Church of Ireland. The principal victims of these laws were Catholics and later Presbyterians.

Civil wars and penal laws

The 17th century was perhaps the bloodiest in Ireland's history. Two periods of civil war (1641-53 and 1689-91) caused huge loss of life and resulted in the final dispossession of the Irish Catholic landowning class and their subordination under the Penal Laws.

In the mid-17th century, Ireland was convulsed by eleven years of warfare, beginning with the Rebellion of 1641, when Irish Catholics rebelled against English and Protestant domination, in the process massacring thousands of Protestant settlers. The Catholic gentry briefly ruled the country as Confederate Ireland (1642-1649) against the background of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms until Oliver Cromwell re-conquered Ireland in 1649-1653 on behalf of the English Commonwealth. Cromwell's conquest was the most brutal phase of a brutal war. By its close, up to a third of Ireland's pre-war population was dead or in exile. As punishment for the rebellion of 1641, almost all lands owned by Irish Catholics were confiscated and given to British settlers. Several hundred remaining native landowners were transplanted to Connacht.

Forty years later, Irish Catholics, known as "Jacobites", fought for James from 1698 to 1691, but failed to restore James to the throne of Ireland, England and Scotland

Ireland became the main battleground after the Glorious Revolution of 1688, when the Catholic James II left London and the English Parliament replaced him with William of Orange. The wealthier Irish Catholics backed James to try to reverse the remaining Penal Laws and land confiscations, whereas Protestants supported William to preserve their property in the country. James and William fought for the Kingdom of Ireland in the Williamite War, most famously at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690, where James's outnumbered forces were defeated. Jacobite resistance was finally ended after the Battle of Aughrim in July 1691. The Penal Laws that had been relaxed somewhat after the English Restoration were re-enacted more thoroughly after this war, as the Protestant elite wanted to ensure that the Irish Catholic landed classes would not be in a position to repeat their rebellions of the 17th century.

Colonial Ireland

Main article Ireland 1691-1801

Subsequent Irish antagonism towards England was aggravated by the economic situation of Ireland in the 18th century. Some absentee landlords managed some of their estates inefficiently, and food tended to be produced for export rather than for domestic consumption. Two very cold winters led directly to the Great Irish Famine (1740-1741), which killed about 400,000 people; all of Europe was affected. In addition, Irish exports were reduced by the Navigation Acts from the 1660s, which placed tariffs on Irish produce entering England, but exempted English goods from tariffs on entering Ireland. Some Irish Catholics remained attached to Jacobite ideology in opposition to the Protestant Ascendancy until the death of "James III & VII" in 1766. Thereafter, the Papacy recognised the Hanoverians as the legitimate rulers. Most of the 18th century was relatively peaceful in comparison with the preceding two hundred years, and the population doubled to over four million.

By the late 18th century, many of the Irish Protestant elite had come to see Ireland as their native country. A Parliamentary faction led by Henry Grattan agitated for a more favourable trading relationship with England and for greater legislative independence for the Parliament of Ireland. However, reform in Ireland stalled over the more radical proposals to enfranchise Irish Catholics. This was enabled in 1793, but Catholics could not yet enter parliament or become government officials. Some were attracted to the more militant example of the French Revolution of 1789. They formed the Society of the United Irishmen to overthrow British rule and found a non-sectarian republic. Their activity culminated in the Irish Rebellion of 1798, which was bloodily suppressed. Largely in response to this rebellion, Irish self-government was abolished altogether by the Act of Union on January 1, 1801.

Union with Great Britain (1801-1922)

In 1800, after the Irish Rebellion of 1798, the British and the Irish parliaments enacted the Act of Union, which merged Kingdom of Ireland and the Kingdom of Great Britain (itself a union of England and Scotland, created almost 100 years earlier), to create the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Part of the deal for the union was that Catholic Emancipation would be conceded to remove discrimination against Catholics, Presbyterians, and others. However, King George III controversially blocked any change.

In 1823, an enterprising Catholic lawyer, Daniel O'Connell, known as "the Great Liberator" began a successful campaign to achieve emancipation, which was finally conceded in 1829. He later led an unsuccessful campaign for "Repeal of the Act of Union".

The second of Ireland's "Great Famines", An Gorta Mór struck the country severely in the period 1845-1849, with potato blight leading to mass starvation and emigration. (See Great Irish Famine.) The impact of emigration in Ireland was severe; the population dropped from over 8 million before the Famine to 4.4 million in 1911.

The Irish language, once the spoken language of the entire island, declined in use sharply in the nineteenth century as a result of the Famine and the creation of the National School education system, as well as hostility to the language from leading Irish politicians of the time; it was largely replaced by English.

Outside mainstream nationalism, a series of violent rebellions by Irish republicans took place in 1803, under Robert Emmet; in 1848 a rebellion by the Young Irelanders, most prominent among them, Thomas Francis Meagher; and in 1867, another insurrection by the Irish Republican Brotherhood. All failed, but physical force nationalism remained an undercurrent in the nineteenth century.

The late 19th century also witnessed major land reform, spearheaded by the Land League under Michael Davitt demanding what became known as the 3 Fs; Fair rent, free sale, fixity of tenure. From 1870 various British governments introduced a series of Irish Land Acts - William O'Brien playing a leading role by winning the greatest piece of social legislation Ireland had yet seen, the Wyndham Land Purchase Act (1903) which broke up large estates and gradually gave rural landholders and tenants ownership of the lands. It effectively ended absentee landlordism, solving the age old Irish Land Question

In the 1870s the issue of Irish self-government again became a major focus of debate under Protestant landowner, Charles Stewart Parnell and the Irish Parliamentary Party of which he was founder. British prime minister William Ewart Gladstone made two unsuccessful attempts to introduce Home Rule in 1886 and 1893. Parnell's controversial leadership eventually ended when he was implicated in a divorce scandal, when it was revealed that he had been living in family relationship with Katherine O'Shea, the long separated wife of a fellow Irish MP, with whom he was father of three children.

After the introduction of the Local Government (Ireland) Act 1898 which broke the power of the landlord dominated "Grand Juries", passing for the first time absolute democratic control of local affairs into the hands of the people through elected Local County Councils, the debate over full Home Rule led to tensions between Irish nationalists and Irish unionists (those who favoured maintenance of the union). Most of the island was predominantly nationalist, Catholic and agrarian. The northeast, however, was predominantly unionist, Protestant and industrialised. Unionists feared a loss of political power and economic wealth in a predominantly rural, nationalist, Catholic home-rule state. Nationalists believed that they would remain economically and politically second class citizens without self-government. Out of this division, two opposing sectarian movements evolved, the Protestant Orange Order and the Catholic Ancient Order of Hibernians.

Home Rule, Easter 1916 and the War of Independence

Home Rule became certain when in 1910 the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) under John Redmond held the balance of power in the Commons and the third Home Rule Bill was introduced in 1912. Unionist resistance was immediate with the formation of the Ulster Volunteers. In turn the Irish Volunteers were established to oppose them and enforce the introduction of self-government.

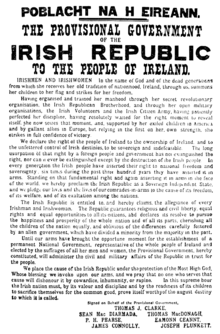

It was issued by the Leaders of the Easter Rising.

In September 1914, just as the First World War broke out, the UK Parliament finally passed the Third Home Rule Act to establish self-government for Ireland, but was suspended for the duration of the war. Nationalist leaders and the IPP under Redmond in order to ensure the implementation of Home Rule after the war, supported the British and Allied war effort against the Central Powers. The core of the Irish Volunteers were against this decision, a majority splitting off into the National Volunteers who enlisted in Irish battalions of the 10th and 16th (Irish) Divisions. Before the war ended, Britain made two concerted efforts to implement Home Rule, one in May 1916 and again with the Irish Convention during 1917-1918, but the Irish sides (Nationalist, Unionist) were unable to agree terms for the temporary or permanent exclusion of Ulster from its provisions.

The period from 1916-1921 was marked by political violence and upheaval, ending in the partition of Ireland and independence for 26 of its 32 counties. A failed attempt was made to gain separate independence for Ireland with the 1916 Easter Rising, an insurrection in Dublin. Though support for the insurgents was small, the violence used in its suppression led to a swing in support of the rebels. In addition, the unprecedented threat of Irishmen being conscripted to the British Army in 1918 (for service on the Western Front as a result of the German Spring Offensive) accelerated this change. (See: Conscription Crisis of 1918). In the December 1918 elections most voters voted for Sinn Féin, the party of the rebels. Having won three-quarters of all the seats in Ireland, its MPs assembled in Dublin on 21 January 1919, to form a thirty-two county Irish Republic parliament, Dáil Éireann unilaterally, asserting sovereignty over the entire island.

Unwilling to negotiate any understanding with Britain short of complete independence, the Irish Republican Army — the army of the newly declared Irish Republic — waged a guerilla war (the Irish War of Independence) from 1919 to 1921. In the course of the fighting and amid much acrimony, the Fourth Government of Ireland Act 1920 implemented Home Rule while separating the island into what the British government's Act termed "Northern Ireland" and "Southern Ireland". In mid-1921, the Irish and British governments signed a truce that halted the war. In December 1921, representatives of both governments signed an Anglo-Irish Treaty. The Irish delegation was led by Arthur Griffith and Michael Collins. This abolished the Irish Republic and created the Irish Free State, a self-governing Dominion of the British Empire in the manner of Canada and Australia. Under the Treaty, Northern Ireland could opt out of the Free State and stay within the United Kingdom: it promptly did so. In 1922, both parliaments ratified the Treaty, formalising independence for the twenty-six county Irish Free State (which went on to become the Republic of Ireland in 1949); while the six county Northern Ireland, gaining Home Rule for itself, remained part of the United Kingdom. For most of the next 75 years, each territory was strongly aligned to either Catholic or Protestant ideologies, although this was more marked in the six counties of Northern Ireland.

Free State/Republic (1922-present)

Main articles: History of the Republic of Ireland; Irish Free State, Republic of Ireland; Names of the Irish state

The treaty to sever the Union divided the republican movement into anti-Treaty (who wanted to fight on until an Irish Republic was achieved) and pro-Treaty supporters (who accepted the Free State as a first step towards full independence and unity). Between 1922 and 1923 both sides fought the bloody Irish Civil War. The new Irish Free State government defeated the anti-Treaty remnant of the Irish Republican Army. This division among nationalists still colours Irish politics today, specifically between the two leading Irish political parties, Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael.

The new Irish Free State (1922–37) existed against the backdrop of the growth of dictatorships in mainland Europe and a major world economic downturn in 1929. In contrast with many contemporary European states it remained a democracy. Testament to this came when the losing faction in the Irish civil war, Eamon de Valera's Fianna Fáil, was able to take power peacefully by winning the 1932 general election. Nevertheless, up until the mid 1930s, considerable parts of Irish society saw the Free State through the prism of the civil war, as a repressive, British imposed state. It was only the peaceful change of government in 1932 that signalled the final acceptance of the Free State on their part. In contrast to many other states in the period, the Free State remained financially solvent as a result of low government expenditure. However, unemployment and emigration were high. The population declined to a low of 2.7 million recorded in the 1961 census.

The Roman Catholic Church had a powerful influence over the Irish state for much of its history. The clergy's influence meant that the Irish state had very conservative social policies, banning, for example, divorce, contraception, abortion, pornography as well as encouraging the censoring of many books and films. In addition the Church largely controlled the State's hospitals, schools and remained the largest provider of many other social services.

With the partition of Ireland in 1922, 92.6% of the Free State's population were Catholic while 7.4% were Protestant.[9] By the 1960s, the Protestant population had fallen by half. Although emigration was high among all the population, due to a lack of economic opportunity, the rate of Protestant emigration was disproportionate in this period. Many Protestants left the country in the early 1920s, either because they felt unwelcome in a predominantly Catholic and nationalist state, because they were afraid due to the burning of Protestant homes (particularly of the old landed class) by republicans during the civil war, because they regarded themselves as British and did not wish to live in an independent Irish state, or because of the economic disruption caused by the recent violence. The Catholic Church had also issued a decree, known as Ne Temere, whereby the children of marriages between Catholics and Protestants had to be brought up as Catholics. From 1945, the emigration rate of Protestants fell and they became less likely to emigrate than Catholics - indicating their integration into the life of the Irish State.

In 1937, a new Constitution of Ireland proclaimed the state of Éire (or Ireland). The state remained neutral throughout World War II (see Irish neutrality) and this saved it from much of the horrors of the war, although tens of thousands volunteered to serve in the British forces. Ireland was also hit badly by rationing of food, and coal in particular (peat production became a priority during this time). Though nominally neutral, recent studies have suggested a far greater level of involvement by the South with the Allies than was realised, with D Day's date set on the basis of secret weather information on Atlantic storms supplied by Éire. For more detail on 1939–45, see main article The Emergency.

In 1949 the state was formally declared the Republic of Ireland and it left the British Commonwealth.

In the 1960s, Ireland underwent a major economic change under reforming Taoiseach (prime minister) Seán Lemass and Secretary of the Department of Finance T.K. Whitaker, who produced a series of economic plans. Free second-level education was introduced by Donnchadh O'Malley as Minister for Education in 1968. From the early 1960s, the Republic sought admission to the European Economic Community but, because 90% of the export economy still depended on the United Kingdom market, it could not do so until the UK did, in 1973.

Global economic problems in the 1970s, augmented by a set of misjudged economic policies followed by governments, including that of Taoiseach Jack Lynch, caused the Irish economy to stagnate. The Troubles in Northern Ireland discouraged foreign investment. Devaluation was enabled when the Irish Pound, or Punt, was established in as a truly separate currency in 1979, breaking the link with the UK's sterling. However, economic reforms in the late 1980s, the end of the Troubles, helped by investment from the European Community, led to the emergence of one of the world's highest economic growth rates, with mass immigration (particularly of people from Asia and Eastern Europe) as a feature of the late 1990s. This period came to be known as the Celtic Tiger and was focused on as a model for economic development in the former Eastern Bloc states, which entered the European Union in the early 2000s. Property values had risen by a factor of between four and ten between 1993 and 2006, in part fuelling the boom.

Irish society also adopted relatively liberal social policies during this period. Divorce was legalised, homosexuality decriminalised, while abortion in limited cases was allowed by the Irish Supreme Court in the X Case legal judgement. Major scandals in the Roman Catholic Church, both sexual and financial, coincided with a widespread decline in religious practice, with weekly attendance at Roman Catholic Mass halving in twenty years. A series of tribunals set up from the 1990s have investigated alleged malpractices by politicians, the Catholic clergy, judges, hospitals and the Gardaí (police).

Northern Ireland

"A Protestant State" (1921-1971)

Main article: History of Northern Ireland

From 1921 to 1971, Northern Ireland was governed by the Ulster Unionist Party government, based at Stormont in East Belfast. The founding Prime Minister, James Craig, proudly declared that it would be "a Protestant State for a Protestant People" (in contrast to the anticipated "Papist" state to the south). Discrimination against the minority nationalist community in jobs and housing, and their total exclusion from political power due to the majoritarian electoral system, led to the emergence of the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association in the late 1960s, inspired by Martin Luther King's civil rights movement in the United States of America. A violent counter-reaction from right-wing unionists and the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) led to civil disorder, notably the Battle of the Bogside and the Northern Ireland riots of August 1969. To restore order, British troops were deployed to the streets of Northern Ireland at this time.

Tensions came to a head with the events of Bloody Sunday and Bloody Friday, and the worst years (early 1970s) of what became known as the Troubles resulted. The Stormont parliament was prorogued in 1971 and abolished in 1972. Paramilitary private armies such as the Provisional Irish Republican Army, the Official IRA, the Irish National Liberation Army, the Ulster Defence Association and the Ulster Volunteer Force fought each other and the British army and the (largely Unionist) RUC, resulting in the deaths of well over three thousand men, women and children, civilians and military. Most of the violence took place in Northern Ireland, but some also spread to England and across the Irish border.

| Irish police forces |

|---|

| Defunct Irish police forces |

| Royal Irish Constabulary (1822–1922) |

| Dublin Metropolitan Police (1836–1925) |

| Irish Republican Police (Irish Republic 1920–1922) |

| Royal Ulster Constabulary (1922–2001) |

| Current Irish police forces |

| Northern Ireland |

| Belfast Harbour Police (1847) |

| Larne Harbour Police (1847) |

| Royal Military Police (1946) |

| Belfast International Airport Constabulary (1994) |

| Police Service of Northern Ireland (2001) |

| Ministry of Defence Police (2004) |

| Republic of Ireland |

| Garda Síochána (1922) |

| Póilíní Airm (1922) |

| Garda Síochána Reserve (2006) |

Direct rule (1971-1998)

For the next 27 years, Northern Ireland was under "direct rule" with a Secretary of State for Northern Ireland in the British Cabinet responsible for the departments of the Northern Ireland executive/government. Principal acts were passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom in the same way as for much of the rest of the UK, but many smaller measures were dealt with by Order in Council with minimal parliamentary scrutiny. Throughout this time the aim was to restore devolution, but three attempts - the power-sharing executive established by the Northern Ireland Constitution Act and the Sunningdale Agreement, the 1975 Northern Ireland Constitutional Convention and Jim Prior's 1982 assembly - all failed to either reach consensus or operate in the longer term.

During the 1970s British policy concentrated on defeating the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) by military means including the policy of Ulsterisation (requiring the RUC and British Army reserve Ulster Defence Regiment to be at the forefront of combating the IRA). Although IRA violence decreased it was obvious that no military victory was on hand in either the short or medium terms. Even Catholics that generally rejected the IRA were unwilling to offer support to a state that seemed to remain mired in sectarian discrimination, and the Unionists plainly were not interested in Catholic participation in running the state in any case. In the 1980s the IRA attempted to secure a decisive military victory based on massive arms shipments from Libya. When this failed - probably because of MI5's penetration of the IRA's senior commands - senior republican figures began to look to broaden the struggle from purely military means. In time this began a move towards military cessation. In 1986 the British and Irish governments signed the Anglo Irish Agreement signalling a formal partnership in seeking a political solution. Socially and economically Northern Ireland suffered the worst levels of unemployment in the UK and although high levels of public spending ensured a slow modernisation of public services and moves towards equality, progress was slow in the 1970s and 1980s, only in the 1990s when progress towards peace became tangible, did the economic situation brighten. By then, too, the demographics of Northern Ireland had undergone significant change, and more than 40% of the population are Catholics.

Devolution and direct rule (1998-present)

More recently, the Belfast Agreement ("Good Friday Agreement") of April 10, 1998 brought a degree of power sharing to Northern Ireland, giving both unionists and nationalists control of limited areas of government. However, both the power-sharing Executive and the elected Assembly have been suspended since October 2002 following a breakdown in trust between the political parties. Efforts to resolve outstanding issues, including "decommissioning" of paramilitary weapons, policing reform and the removal of British army bases are continuing. Recent elections have not helped towards compromise, with the moderate Ulster Unionist and (nationalist) Social Democrat and Labour parties being substantially displaced by the hard-line Democratic Unionist and (nationalist) Sinn Féin parties.

On July 28 2005, the Provisional IRA announced the end of its armed campaign and on September 25 2005 international weapons inspectors supervised the full disarmament of the PIRA.

Flags in Ireland

The state flag of the Republic of Ireland is the Irish Tricolour. This flag, which bears the colours green for Roman Catholics, orange for Protestants, and white for the desired peace between them, dates back to the middle of the 19th century.[10]

The state flag applying to Northern Ireland is the Union Flag of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. The Ulster Banner is sometimes used as a de facto regional flag for Northern Ireland.

The Tricolour was first unfurled in public by Young Irelander Thomas Francis Meagher who, using the symbolism of the flag, explained his vision as follows: "The white in the centre signifies a lasting truce between the "Orange" and the "Green," and I trust that beneath its folds the hands of the Irish Protestant and the Irish Catholic may be clasped in generous and heroic brotherhood". Fellow nationalist John Mitchel said of it: "I hope to see that flag one day waving as our national banner."

After its use in the 1916 Rising it became widely accepted as the national flag, as was used officially by the Irish Republic (1919-21) and the Irish Free State (1922-37).

In 1937 when the Constitution of Ireland was introduced, the Tricolour was formally confirmed as the national flag: "The national flag is the tricolour of green, white and orange." While the Tricolour today is the official flag of the Republic of Ireland, as a state flag it does not apply to the entire island of Ireland.

Since Partition, there has been no universally-accepted flag to represent the entire island. As a provisional solution for certain sports fixtures, the Flag of the Four Provinces enjoys a certain amount of general acceptance and popularity.

Historically a number of flags have been used, including:

- Saint Patrick's Flag (St Patrick's Saltire, St Patric's Cross) which was the flag sometimes used for the Kingdom of Ireland and which represented Ireland on the Union Flag after the Act of Union,

- a green flag with a harp (used by most nationalists in the 19th century and which is also the flag of Leinster),

- a blue flag with a harp used from the 18th century onwards by many nationalists (now the standard of the President of Ireland), and

- the Irish Tricolour.

St Patrick's Saltire was formerly used to represent the island of Ireland by the all-island Irish Rugby Football Union (IRFU), before adoption of the four-provinces flag. The Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA) uses the Tricolour to represent the whole island.

See also

|

Footnotes

- ^ Moody, T.W. & Martin, F.X., eds. (1995). The Course of Irish History. Roberts Rinehart. pp. 31–32. ISBN 1-56833-175-4.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Geneticists find Celtic links to Spain and Portugal www.breakingnews.ie, 2004-09-09. Retrieved 2007-04-01.

- ^ Myths of British ancestry Stephen Oppenheimer. October 2006, Special report. Retrieved 2007-04-01.

- ^ Y-chromosome variation and Irish origins (pdf)

- ^ "Yes, the Romans did invade Ireland". British Archaeology.

- ^ *Philip Rance, ‘Attacotti, Déisi and Magnus Maximus: the Case for Irish Federates in Late Roman Britain’, Britannia 32 (2001) 243-270

- ^ *Carmel McCaffrey, Leo Eaton "In Search of Ancient Ireland" Ivan R Dee (2002)PBS 2002

- ^ * Donnchadh Ó Corráin 'Ireland Before the Normans' Gill and MacMillan (1980)

- ^ M.E.Collins, Ireland 1868-1966, (1993) p431)

- ^ The Irish State www.irlgov.ie

References

Irish Kings and High Kings, Francis John Byrne, Dublin, 1973.

- A New History of Ireland: I - PreHistoric and Early Ireland, ed. Daibhi O Croinin. 2005

- A New History of Ireland: II- Medieval Ireland 1169-1534, ed. Art Cosgrove. 1987.

- Braudel, Fernand, The Perspective of the World, vol III of Civilization and Capitalism (1979, in English 1985)

- Plumb, J.H., England in the 18th Century, 1973: "The Irish Empire"

- Murray N. Rothbard, For a New Liberty, 1973, online.

Further reading

- S.J. Connolly (editor) The Oxford Companion to Irish History (Oxford University Press, 2000)

- Tim Pat Coogan De Valera (Hutchinson, 1993)

- Norman Davies The Isles: A History (Macmillan, 1999)

- Nancy Edwards, The archaeology of early medieval Ireland (London, Batsford 1990).

- R. F. Foster Modern Ireland, 1600-1972

- J.J.Lee The Modernisation of Irish Society 1848-1918 (Gill and Macmillan)

- FSL Lyons Ireland Since the Famine

- Dorothy McCardle The Irish Republic

- T.W. Moody and F.X. Martin "The Course of Irish History" Fourth Edition (Lanham, Maryland: Roberts Rinehart Publishers, 2001).

- James H. Murphy Abject Loyalty: Nationalism and Monarchy in Ireland During the Reign of Queen Victoria (Cork University Press, 2001)

- http://www.ucc.ie/celt/published/E900003-001/ - the 1921 Treaty debates online.

- John A. Murphy Ireland in the Twentieth Century (Gill and Macmillan)

- Frank Packenham (Lord Longford) Peace by Ordeal

- Alan J. Ward The Irish Constitutional Tradition: Responsible Government & Modern Ireland 1782-1992 (Irish Academic Press, 1994)

- Robert Kee The Green Flag Volumes 1-3 (The Most Distressful Country, The Bold Fenian Men, Ourselves Alone)

- Carmel McCaffrey and Leo Eaton In Search of Ancient Ireland: the origins of the Irish from Neolithic Times to the Coming of the English (Ivan R Dee, 2002)

- Carmel McCaffrey In Search of Ireland's Heroes: the Story of the Irish from the English Invasion to the Present Day (Ivan R Dee, 2006)

- Hugh F. Kearney Ireland:Contested Ideas of Nationalism and History (NYU Press, 2007)]

- Nicholas Canny "The Elizabethan Conquest of Ireland"(London, 1976) ISBN 0-85527-034-9.

External links

- http://www.breakingnews.ie/2004/09/09/story165780.html

- http://www.prospect-magazine.co.uk/article_details.php?id=7817

- http://www.pbs.org/wnet/ancientireland/

- History of Ireland: Primary Documents

- History of Ireland guide

- Ireland Under Coercion - "The diary of an American", by William Henry Hurlbert, published 1888, from Project Gutenberg

- The Story of Ireland by Emily Lawless, 1896 (Project Gutenberg)

- Timeline of Irish History 1840-1916 (1916 Rebellion Walking Tour)

- A Concise History of Ireland by P. W. Joyce