Northern Ireland Conflict

| date | 1969-1998 |

|---|---|

| location | Northern Ireland |

| exit | Armistice ( Good Friday Agreement ) |

| conflict parties | ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

The Northern Ireland Conflict ( English The Troubles , Irish Na Trioblóidí ) is a civil war-like identity and power struggle between two population groups in Northern Ireland :

- Protestants , mostly descendants of English and Scottish immigrants wishing to remain a part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland as Unionists or Loyalists ( see Plantation of Ulster ).

- Catholics who, as republicans , advocate for a united Ireland, i.e. for the detachment from the United Kingdom and the union of Northern Ireland with the Republic of Ireland .

The conflict between these two groups ultimately goes back to the English conquest of Ireland, so it existed long before Northern Ireland was founded after the Irish War of Independence in 1921, and dominated Northern Ireland and British politics from 1969 to 1998. The armed conflicts ended with the Good Friday Agreement of 1998 ended for now. Due to Brexit , it is uncertain today (as of 2021) whether the stability of this agreement can be maintained.

The two groups “Catholics” and “Protestants”

The most salient feature of Northern Ireland is the segregation of the population into two broad groups based on ethnicity and creed .

The terms ' Catholic ' and ' Protestant ' are used in Northern Ireland to distinguish between two groups in society that have opposing social, political, economic and ultimately religious attitudes. These cultures evolved from the contrast between the native Irish (who were poor, rural, and Catholic) and the colonizing Scottish or English settlers (wealthy, industrial, Protestant). The denomination terms finally got their ethnic ring from the self-definition of the settled settlers as “Protestants”. In fact, the Northern Irish communities can be described as ethnic groups – ethnic groups understood here in the sense of an organized group that is more than average aware of belonging to their own group in contrast to the “others” and who are aware of these “others” in religion, customs, historical myths and feels superior to territorial claims.

Although the number of active participants in the Northern Ireland conflict was comparatively small and the paramilitary organizations that claimed to represent the population were generally not representative, the armed conflict touched the lives of most people in Northern Ireland on a daily basis until 1998 and occasionally spread as far as Britain or the Republic of Ireland. Between 1969 and 2001, according to Malcolm Sutton's Index of Deaths from the Conflict in Ireland , 3,532 people died as a result of the violence; about half of the victims were civilians. Even after the ceasefire of 1998, the political and social attitudes of many people are still shaped by the conflict.

settlement geography

This division is even reflected in the geography of settlement : generally speaking, the north-eastern areas (particularly the outskirts and parts of Belfast and the County Antrim coast ) are now Protestant and the western (around County Derry and County Tyrone ) Catholic. The Northeast is much more industrialized than the rural West. Almost all major cities are Protestant strongholds (except for Derry and Newry ). This also includes Belfast, by far the largest conurbation. These larger cities, in turn, are often segregated into Protestant and Catholic neighborhoods (e.g. in Belfast Falls Road (Catholic-Irish) and The Shankill (Protestant-British)).

prehistory

Prehistory up to 1800

As early as 1169, the eastern part of Ireland was conquered and ruled by the English. After the Nine Years' War , the Earls fled in 1607 , after which English, Welsh and Scots were systematically settled in Ulster , which led to the dispossession of the Irish population in a relatively short time.

Unsuccessful uprisings by the Catholic Irish led to their further disenfranchisement. After the victory of the Protestant King Wilhelm III. of Orange over the previously overthrown Catholic King James II at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690, which is revived every year on July 12 at the Orange Marches of the Protestants, the so-called Penal Laws were enacted in 1695, which the Catholic religious practice and promoted Protestant land ownership. From 1728, Catholics no longer had the right to vote. The Society of United Irishmen , founded in 1791 , campaigned for an independent Ireland, but their rebellion in 1798 failed. The Union Act of 1800 dissolved Ireland as a state.

Striving for autonomy from 1801 to 1920

From 1801 Ireland was part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland .

With the rise of nationalism in Europe in the 19th century, nationalist groups also formed in Ireland, which advocated secession from the Union and an independent Ireland. The Home Rule Movement , led by Charles Stewart Parnell , campaigned for political autonomy for the island. The liberal British Prime Minister William Gladstone took up the idea, but failed twice (1886 and 1895) in the British Parliament with his bills. The Protestants in the province of Ulster in particular resisted autonomy , as the vast majority of Irish people were Catholic.

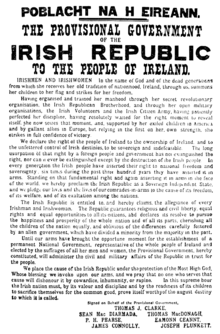

After the failure of the Home Rule movement, Irish politician and journalist Arthur Griffith founded Sinn Féin in 1905 , which occupied the post office in Dublin in 1916 and proclaimed a provisional government of Ireland. This so-called Easter Rising was put down by British troops after five days and the leaders were executed. The Sinn Féin and its affiliated Irish Republican Army (IRA) gained a lot of support from popular outrage at the executions.

In the 1918 general election , Sinn Féin won 80% of the Irish seats. As announced during the election campaign, however, the MPs did not take their seats in the House of Commons, but constituted themselves in 1919 as Dáil Éireann , the first Irish parliament since 1801, and proclaimed the independent Irish Republic. The British Parliament immediately declared the Dáil illegal. The first IRA was formed as the military arm of Sinn Féin in 1919 and carried out attacks on British Government buildings and officials in Northern Ireland. The Black and Tans paramilitary group was formed by the British state and attacked Sinn Féin and the IRA. Increasing violence on both sides led to the Irish War of Independence , which lasted until 1921.

Partition of Ireland 1921

In order to prevent a civil war between Unionists (UVF) and Republicans, two Home Rule parliaments were planned. For this reason, six of the nine counties of Ulster, with a predominantly Protestant population, were given their own parliament as early as 1920 under the Government of Ireland Act . To this day, nationalists maintain that only six Ulster counties were deliberately made part of Northern Ireland, as this would ensure a two-thirds Unionist majority (whereas in Ulster as a whole, both communities would have been roughly equally represented). The Unionists, on the other hand, point to the election results of 1918 and the constituencies they won at that time, which roughly corresponded to the shape of Northern Ireland.

From July 1921, British Prime Minister David Lloyd George began negotiations with Sinn Féin, chaired by Arthur Griffith and Éamon de Valera . In late 1921, after five months of talks, a treaty of independence was signed by Lloyd George, Griffith and Michael Collins , known as the Anglo-Irish Treaty . The south of Ireland was granted Free State status within the British Empire . In addition, the treaty provided for a border commission, which in 1921 was to make a final decision on the course of the inner-Irish border. However, since the parties could not agree on how to proceed, the commission did not change anything about the demarcation.

The Irish Free State , which became the Republic of Ireland in 1948, viewed the partition as only temporary; until before the outbreak of the Irish Civil War in 1922, Collins supported the IRA units in the north in an armed campaign against the new Northern Irish state. However, these contacts ceased at the beginning of the civil war. The 1937 constitution drafted by de Valera raised a territorial claim to all of Ireland, which was only rescinded with the Good Friday Agreement in 1998.

Northern Ireland until 1965

The Protestants, who see themselves as pro-British Unionists or Loyalists, made of Northern Ireland, as the first Prime Minister of Northern Ireland James Craig said, "a Protestant state for a Protestant people". The Free State's constitution of 1937 increased the Unionists' fear of being swallowed up by it. This has resulted in Catholics, most of whom see themselves as pro-Irish nationalists or Republicans , as aliens or even enemies of the state. As early as 1922, parliament passed draconian penal laws that nipped any republican agitation in the bud. Disappointment among the Catholic minority in Northern Ireland was great, and discrimination against Catholics there increased.

But all the changes to local electoral law that the Unionists made from 1920 onwards were directed not only against Catholics but also against all non-Unionists in general (such as the Labor movement). So the Unionists abolished local proportional representation and introduced British first-past-the-post voting for Stormont. Combined with unrepresentative constituency draws, this disproportionately favored unionist over nationalist candidates. Northern Ireland's right to vote was also heavily tied to home ownership, which also discriminated against the mostly poorer Catholics who rented their homes. For example, Derry/Londonderry provided a Unionist mayor despite the Nationalists having a far larger proportion of the city's population. Through all these measures the Unionists ensured that from 1921 to 1972 Northern Ireland was governed uninterruptedly by a single party, the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP), which faced no significant opposition in Parliament.

There was also discrimination in the allocation of jobs or the allocation of social housing. The segregation of the two sections of the population was also promoted by the school policies of the churches. When Northern Ireland was founded, mixed denominational schools were envisaged, but this was strongly opposed and thwarted by the churches from the outset.

In gratitude for Northern Ireland's willingness to go to war with Britain against Hitler (unlike the Free State of Ireland, which remained neutral), Westminster guaranteed the province 's stay in the UK through the Ireland Act 1949. This commitment brought relief to many Unionists, since the Free State in the south had just finally declared itself a republic, severing its last ties with Great Britain. On the Irish Catholic side, however, the Ireland Act caused bitterness.

While Northern Ireland had experienced a temporary economic boom during the Second World War due to the armaments industry (shipbuilding, naval bases , air force bases ), from 1945 the large cities of Belfast and Derry in particular went into decline. The Catholic population was hit particularly hard.

In the 1950s there were attacks by the IRA in the Border Campaign and by Saor Uladh . At the time, however, the IRA had little popular support and by the first half of the 1960s had shrunk to a small splinter group that opposed supporters and opponents of Marxist ideologies.

From 1966 to the 1998 Good Friday Agreement

Appearance of the Protestant UVF

The beginnings of the conflict can be traced back to the re-formation of the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) in 1966. This illegal, loyalist and paramilitary organization was founded by some radical Protestants who believed in an impending IRA revival due to the 50th anniversary of the Easter Rising . The UVF began a campaign of intimidation against a Catholic liquor store on Shankill Road . Sectarian graffiti such as "Papist" and "This house is occupied by a Taig" were sprayed on the wall next to the shop, even though Protestants actually lived there. The UVF issued a letter two weeks after a Molotov cocktail attack that left a 77-year-old Protestant widow dead from her burns and for which the UVF blamed the IRA:

“From this day on we declare war on the IRA and its factions. Known IRA men are executed by us mercilessly and without hesitation. (...) We do not tolerate any interference - from any quarter whatsoever - and warn the authorities against further soothing speeches. We are heavily armed Protestants and fully committed to our cause.”

The UVF later claimed responsibility for the shooting death of 28-year-old John Patrick Scullion in West Belfast. 18-year-old bartender Peter Ward, also from West Belfast, was the second victim of a UVF shooting that left three other men shot and seriously injured. Victor Arbuckle, who was shot dead by UVF loyalists during street riots on Belfast's Shankill Road in October 1969 at the age of 29, was the first Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) officer killed in that conflict. The UVF was also responsible for a series of attacks on power stations in Northern Ireland during 1969. The attacks were designed to look like an IRA action to turn moderate Unionists against the proposed reforms of Terence O'Neill 's government . O'Neill then resigned as leader of the Ulster Unionist Party and as Prime Minister in April 1969.

Civil rights and Catholic protests

In the late 1960s, increasing numbers of Catholics and Protestants began to demonstrate against injustice and inequality in Northern Ireland. The opening of the country to the outside world, particularly through television, changed their perspective. Inspired by Martin Luther King 's peaceful civil rights movement from the USA and the student protests in Europe, the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA) was founded in 1967. A year later, the student organization People's Democracy (PD), which also fought for civil rights, followed. A prominent speaker was later MP Bernadette Devlin McAliskey .

NICRA had announced a demonstration in Derry for October 5, 1968. The Apprentice Boys of Derry protestant fraternity announced a counter-demonstration at the same time and in the same place. As a result, both demonstrations were banned. Around 2,000 Catholic civil rights activists flouted the ban and began a peaceful protest march. They were surrounded and brutally clubbed by the Royal Ulster Constabulary in Duke Street. More than 100 demonstrators were injured.

The following protest marches by Catholics were also violently put down by the RUC and the local authorities. The British government then set up a commission of inquiry. Their report ( Disturbances in Northern Ireland. Report of the Commission appointed by the Governor of Northern Ireland ), commonly known as the Cameron Report after the chairman of the Commission, Sir John Cameron , documented the abuses by the police, but had no political or legal consequences.

Initially, the then Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, Terence O'Neill, was quite open to the civil rights activists' moderate campaign and promised reforms for Northern Ireland. However, he met with strong opposition from many hard-liners among the Unionists, such as William Craig and Ian Paisley , who accused him of being a "traitor". Indeed, many unionists saw the civil rights movement as a Trojan horse of the IRA and believed in a republican conspiracy to unify with the republic. Neutral observers consider this a fatal misjudgment, since the civil rights activists did not necessarily want to make Northern Ireland more Irish and for them the clerical republic was just as in need of reform as Northern Ireland; they were primarily looking for a connection to the democratic conditions in Great Britain. The IRA played no role at this point. Although it had been founded around 1919, it had begun to renounce violence after the failed Border Campaign of 1956-1962. The events therefore came as a complete surprise to them. The economic decline (low direct investments , emigration ) worsened and again led to higher unemployment. In the course of the clashes, since the escalation began in the late 1960s, up to 4,000 people have died.

Escalation of violence from 1969

In 1969 there were increasing unrest and riots in the communities. In January, a People's Democracy (PD) march from Belfast to Londonderry ('Derry') was attacked by Loyalists in Burntollet , County Londonderry . The RUC was accused of not coming to the aid of the attacked marchers on the PD side, but rather tolerating the attacks. The RUC was therefore increasingly viewed as an opponent by the civil rights movement. As a result, barricades were erected in the nationalist areas of Derry and Belfast in the months that followed.

Things escalated on 12 August 1969 when in Derry, Northern Ireland, Protestants stormed the Catholic area of Bogside and provoked the Catholic residents by celebrating the 280th anniversary of the defense of Derry. The Catholic population barricaded themselves and fought street battles with the Protestants and the RUC for two days. In order to relieve the Bogside, many Catholic working-class districts in the rest of the country now showed their solidarity and also started unrest in Belfast, for example. There, in particular, many Catholics lived in working-class districts with high unemployment, including among young people.

The situation escalated further after a hand grenade was thrown at a police station in Derry. The RUC then deployed three armored cars with machine guns and killed a nine-year-old boy with ricochets from one of the machine guns . Civil war-like riots followed, with loyalists burning down entire Catholic streets (including Bombay Street and Madrid Street) and residents on both sides being driven out of their homes . Ghettos emerged in which Protestants or Catholics still live almost exclusively today. After two days of unrest in which eight people died, 750 were injured and 1,505 Catholic families were displaced, five times the number of Protestants, the new Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, James Chichester-Clark , called the British army for help after the Northern Ireland police failed been to end the riots.

The army was initially warmly welcomed by many Catholics in Belfast and Derry, who saw them as neutral protectors from the unionist mob and the partisan RUC. After the army was deployed, the situation calmed down quickly. However, Britain was thus forced to take an active part in the conflict and to mediate, having practically left the conflict to local government since the partition of Ireland. British military officials warned that the positive mood on the streets would not last forever and that politicians must solve the problem. However, because the army was sent to Northern Ireland with no political agenda and was only tasked with restoring law and order, it was quickly viewed by Catholics as an extension of the Stormont regime, working closely as a security body with the Northern Irish government and police. Thus she lost her initially neutral position in the conflict.

In the wake of the Northern Ireland Troubles, many Republicans in Northern Ireland felt that the IRA had failed the Catholic and Nationalist communities by failing to prevent Loyalists from attacking Catholic streets and burning their homes. The traditionalists and militarists accused the IRA leadership in Dublin of failing to bring in arms, planning or personnel to defend Catholic streets against violent attacks because of its purely political strategy.

In December 1969, the IRA split into the Provisional IRA (PIRA), made up of traditional militarists, and the Official IRA (OIRA), made up of what was left of the pre-split Marxist leadership and their supporters. From the start there was an ongoing feud between the Provos and the Official IRA as both factions vied for control of Nationalist areas, particularly in Belfast. However, the Provisionals quickly gained the upper hand due to their profile as the more reliable defenders of the Catholic community. From now on, when the IRA was mentioned, the PIRA was usually meant.

Due to the incidents in 1969, the Provos received enough support and support that, from the year 1970, the PIRA finally became a serious military opponent in a kind of guerrilla warfare . Money for the Provisionals' underground army often came from organizations based in the United States ( NORAID ), where many people of Irish descent reside.

The Provisional IRA leadership had planned from the outset to expand its activities and move from purely defensive operations to an offensive campaign aimed at overthrowing British rule in Northern Ireland and bringing about the reunification of Ireland. This became possible as the relationship between the Catholic community and the British Army deteriorated rapidly in the course of 1970. This deterioration was due to the soldiers' harsh treatment of Catholics and nationalists, as the army, influenced by the RUC, was now often overly aggressive in fighting the republican paramilitaries. An example of this was the three-day curfew of the Lower Falls in West Belfast: the army sealed off the Lower Falls on 3-5 July 1970 with up to 3000 British soldiers and carried out an aggressive search for weapons - an episode that has become popularly known received as the "Rape of the Falls." Five civilians were killed. More than 60 people were injured in fighting between the soldiers and the Official IRA, which at the time was still the dominant faction of the IRA in this part of Belfast. Over 300 people were arrested, with the army spraying tons of tear gas in the area .

After this incident, the IRA shifted its strategy from "defense" to "retaliation" and in January 1971 began launching attacks on army and RUC patrols. On February 5, 1971, in Belfast, the Provisionals killed the first British soldier in a shootout in the New Lodge area, Robert Curtis. After that, exchanges of fire between the IRA and the security forces were the order of the day. By July 1971, ten British soldiers had died at the hands of the IRA in Belfast alone.

Internment policy from 1971

On 9 August 1971, following a decision by the new Prime Minister of Northern Ireland , Brian Faulkner and his government, the British Army began Operation Demetrius , which meant the introduction of internments to help arrest IRA leaders. The following day the IRA held a press conference at a school in the Ballymurphy area of Belfast and declared that the operation was a failure. There she said: “We lost a brigade officer, a battalion officer …; the rest are just volunteers, or as they say in the British Army, privates”.

This internment policy , i.e. the preventive detention of suspects without charge or trial, further fueled the violence. During the first three days following the introduction of the internments there was violent rioting and fighting in the Nationalist areas of Northern Ireland as British troops entered these areas to arrest paramilitary suspects. A total of 17 people were killed in the clashes. During the remainder of 1971, 37 British soldiers and 97 civilians were killed. In 1972 the death toll increased further to a total of 479, most of whom (247) were civilians. This year was the bloodiest of the entire conflict. However, the period was also a losing one for the IRA.

Peak of violence and end of Stormont in 1972

The shooting dead of 13 unarmed people by British paratroopers at a demonstration in the northern Irish city of Derry on 30 January 1972 , Bloody Sunday , increased support for the IRA by large sections of the Catholic population, and its consequent recruitment declined strong to. The fact that a commission of inquiry set up by the British government initially acquitted the soldiers of any guilt caused outrage and bitterness; It was not until 2010 that Prime Minister David Cameron admitted after a new investigation ( Saville Report ) that the victims were innocent and that the British soldiers had acted criminally.

Because of the increasingly violent escalation of violence in 1972, Stormont , the Parliament of Northern Ireland, was ousted and later dissolved. After more than 50 years of self-government, Northern Ireland was governed from London by a Northern Ireland Minister ( Direct Rule ) from March 24 , after three Northern Irish Prime Ministers had been worn out with O'Neil, Chichester-Clark and Faulkner since 1969 in a very short time , the same number of Premiers as from 1921 to 1963.

From June 26 to July 10, 1972, the leadership of the Provisional IRA declared a ceasefire. In July 1972, IRA leaders Seán Mac Stíofáin, Dáithí Ó Conaill, Ivor Bell, Seamus Twomey, Gerry Adams and Martin McGuinness met a British delegation led by William Whitelaw for secret talks in London. IRA leaders refused to agree to a peaceful solution that did not include a commitment to British withdrawal (first to barracks, then out of Ireland) and release of Republican prisoners. The British rejected these demands and broke off the talks. The ceasefire ended when there was open confrontation between the IRA and the British Army in the Lenadoon area of Belfast. IRA men opened fire on the soldiers after an alleged provocation by the army. Seán Mac Stíofáin, the IRA Chief of Staff , officially announced the end of the ceasefire that night in response to the events in Belfast.

In addition to attacks on the British Army, bombings of commercial targets such as shops and companies were a central part of the IRA campaign. The most devastating event was Bloody Friday on July 21, 1972, when 22 bombs went off in Belfast, killing nine people and injuring 130. Although, according to the organization itself, most of the IRA attacks on commercial targets were not carried out to kill or injure people, and there were sometimes anonymous bomb warnings, the attacks repeatedly claimed victims among bystanders.

Operation Motorman

By 1972 the Provisional IRA had de facto control of many Nationalist areas in Northern Ireland and provided permanent checkpoint and barricade crews. But these "no go areas" like Free Derry and Free Belfast, which the paramilitaries also used as safe havens, were recaptured by the British Army in response to the 1972 Bloody Friday bombings in a major operation called Operation Motorman. The British now began to build fortified posts in Republican areas. In doing so, they severely restricted the freedom of movement of the IRA.

Thus the number of British soldiers killed by the IRA fell sharply after 1972. In 1972, the Provisional IRA killed 145 members of the security forces. By 1974, that number had dropped to 40. In addition, the popular disgust provoked by Bloody Friday forced the Provisionals to temporarily refrain from further car bombings.

In 1973 a referendum was held in Northern Ireland where voters had to choose between remaining in the UK and joining the Republic of Ireland. The referendum was in favor of the UK, but it was almost completely boycotted by the Catholic population.

In May 1974 the attempt agreed in the Sunningdale Agreement to form a joint government of Unionists and Nationalists failed. The new Northern Ireland government resigned after a few months when a general strike by Unionist workers ( Ulster Workers' Council Strike ) largely paralyzed the province.

The 1975 ceasefire

As a result of renewed secret negotiations between the IRA leadership and the British government, the Provisional IRA announced a new ceasefire of January 1975-January 1976. In return, the British encouraged and supported incident centers , which became the de facto offices of Sinn Féin in the nationalist parts of Northern Ireland, in the hope that this would encourage the development of the political wing within the republican movement. In practice, however, the ceasefire did little to reduce violence. The loyalist paramilitaries feared collusion between the IRA and the British government. At the same time, they intensified their killings of Catholic civilians, killing more than 300 people between 1974 and 1976. The IRA responded with retaliatory attacks on Protestant civilians. She carried out a total of 91 sectarian murders between 1974 and 1976.

Furthermore, in mid-1975, the Provos attacked the Official IRA that still existed in order to finally smash this organization. The ensuing feud resulted in the deaths of 11 Republican paramilitaries and a number of civilians. In addition, the IRA's discipline was collapsing during this period, which sent some of the IRA volunteers into organized crime. In addition, British intelligence was also able to recruit more informants within the IRA during the ceasefire.

Therefore, the IRA announced the end of the ceasefire in January 1976.

Hunger strikes and the rise of Sinn Féin

IRA prisoners convicted after March 1976 no longer enjoyed special status as the British government had ended its internment policy, but were treated in prison as 'normal' criminals. In response, over 500 inmates refused to wash or wear prison uniforms (“ ceiling protest ” and “ dirty protest ”). These protests culminated in a second hunger strike in 1981 : seven IRA and three INLA members starved to death for recognition of political status. A hunger striker ( Bobby Sands ) and anti -H-block activist Owen Carron were elected to the British Parliament and two other prisoners on hunger strike to the Irish Dáil. There have also been walkouts and large demonstrations across Ireland to show sympathy for the hunger strikers. More than 100,000 people attended the funeral at Milltown Cemetery in Belfast for Sands , the first hunger striker to die.

After the IRA hunger strike's success in mobilizing support and winning seats in Parliament, Republicans devoted increasing amounts of time and resources to elections after 1981. As a result, the Sinn Féin party gained increasing importance within the republican movement. Sinn Féin summed up this policy at an Ard Fheis (annual party convention) that same year: "with the ballot in one hand and the Armalite in the other" .

supergrasses

In the 1980s, the paramilitaries were hit hard by the security forces' use of special informants called "supergrasses" (super snitches). These were men who, once arrested, feared a lengthy prison sentence, being recruited as spies by the various British security services, or who were offered immunity from prosecution in exchange for testifying against other suspects. Although there were ultimately few convictions from the Supergrass system, it has resulted in many paramilitaries being harassed or arrested and spending long periods in prison awaiting trial.

This tactic was first used in 1981 after the arrest of Belfast IRA man Christopher Black. After being assured he was safe from prosecution, Black made testimonies that led to 38 arrests. On August 5, 1983, 22 members of the IRA were sentenced to a total of 4,000 years in prison on Black's charges. Eighteen of those convictions were overturned on appeal on July 17, 1986. Up to 600 paramilitaries have been arrested under the Supergrass settlement.

Subsequent fears of informers did much to reduce the activity of IRA units in Belfast and Derry.

peace process

From the early 1980s, the Irish and British governments worked more closely together to reach a political settlement in the Northern Ireland conflict that was acceptable to all sides. With the Anglo-Irish Agreement of 15 November 1985, the Irish government was given an advisory role in the Northern Ireland conflict for the first time and at the same time confirmed that the constitutional status of Northern Ireland would not be changed without the will of the Northern Irish majority. The agreement was signed by British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and Irish Prime Minister Garret FitzGerald at Hillsborough Castle and was intended to bring political peace to the Northern Ireland conflict.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the loyalist paramilitaries intensified their killings of Catholics. In response, the IRA attempted to assassinate loyalist leaders. She wanted to avoid sectarian reprisals against Protestant civilians, such as occurred in the 1970s. However, in a 1993 attempt to wipe out the leadership of the Ulster Defense Association, she committed one of the worst atrocities of the entire IRA campaign in a bombing of a fish shop on Shankill Road where UDA men were said to meet regularly. However, the bomb exploded prematurely, killing one of the bombers, Thomas Begley, and nine Protestant civilians. Another 58 were injured. The loyalist paramilitaries were not in the building.

The spiral of violence created by the killings between the IRA and the Loyalists only ended in August 1994 after the IRA announced a unilateral ceasefire.

From 1988 onwards, Gerry Adams held regular secret talks with John Hume , leader of the moderate Social Democratic and Labor Party (SDLP), and secret talks were also held with British officials and the Irish government.

The IRA finally announced an indefinite ceasefire in 1994, on condition that Sinn Féin would be involved in political talks for a solution. The Protestant paramilitaries followed this step a little later. When Sinn Féin was not involved as requested, the IRA withdrew its ceasefire from February 1996 to July 1997. During this time she undertook several bombings and shootings. After a renewed ceasefire, Sinn Féin was brought back into the "peace process" that eventually culminated in the 1998 Good Friday Agreement .

The representatives of SF and SDLP now wrestled with UUP and DUP to find a solution in Northern Ireland. The Republic of Ireland and Great Britain staked out their territory, but the legitimate interests of both Unionists and Republicans had to be taken into account in the long-running negotiations. London asked Dublin to refrain from the constitutional goal of reunifying Ireland.

To the surprise of many observers, a consensus was reached on both sides with the Good Friday Agreement . the political demands of Great Britain into account. London's concession was in return police reform and increased Sinn Féin involvement in the governance of Northern Ireland. Separate referendums in Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland showed that the population was tired of the violence. Life in Northern Ireland then began to return to normal.

In June 2007, the UK government set up a cross-party group called the Consultative Group on the Past to develop proposals for societal reconciliation in Northern Ireland. Their final report, when it was published in January 2009, sparked public debate in the UK by proposing that a lump sum be paid to all relatives of those killed in politically motivated violence, whether they were civilian victims or paramilitaries.

On 12 April 2010 the responsibility for the police and judiciary of Northern Ireland was placed under the direction of a dedicated Northern Ireland Minister of Justice , which had not previously been the case. This seems to have settled one last point of contention, namely that of the independence of the Northern Irish police and judiciary.

Development since 2000

From 2000 to 2013

The new government has been dissolved several times since it was convened in 1999. In 2002, politicians from what was then the largest parliamentary group, the Ulster Unionists, refused to continue sitting in parliament with representatives of the IRA-affiliated Sinn Féin ; the assembly has been overridden. The reason was the suspicion that the IRA had operated espionage in the government buildings. The investigations were ultimately dropped without finding any results, but they brought to light in 2005 that the Sinn Féin office manager in Stormont, Denis Donaldson , had worked for years as an informant for British secret services. A few months after the revelations, Donaldson was found murdered.

Since then, the Democratic Unionist Party under Ian Paisley has risen to become the strongest party. This made Paisley the lead candidate for the post of Chairman of the Assembly ( First Minister ). It was his uncompromising stance, and that of his party, that power could not be shared with Sinn Féin. This should only happen when they have implemented all the articles of the Good Friday Agreement, such as the complete disarmament of the IRA and full support for the Northern Ireland police .

On July 28, 2005 , the IRA declared the armed struggle over. However , two smaller radical splinter groups, the Real IRA and the Continuity IRA , remain prone to violence and maintain a state of war to this day. Riots in Dublin linked to the Northern Ireland conflict injured 25 people on the last weekend of February 2006, followed by a subsequent apology from the Sinn Fein boss.

Again and again there are incidents that are directly or indirectly related to paramilitary organizations. The tensions between the two ethnic groups often end in acts of violence, and not just at the parades. For example, in May 2006, 15-year-old Catholic Michael McIlveen was beaten to death with baseball bats by Protestant youths. In early 2007, the IRA officially disarmed.

Thereafter, on 28 January 2007, at a special party conference in Dublin, Sinn Féin recognized the Police of Northern Ireland in a historic vote of 2000 delegates. In so doing, she overcame a major obstacle on the way to re-establishing a regional government in Northern Ireland. As a result, the British Protestant Democratic Unionist Party agreed on 26 March 2007 (St Andrews Accord) to a power-sharing agreement with Sinn Féin.

On 3 May 2007 the leadership of the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) finally declared its renunciation of the use of force. This means that the UVF will cease to exist as a paramilitary organization. Nevertheless, they will not give up their weapons, only make them inaccessible.

On the night of July 30th/31st, 2007, the British Army ended its deployment in Northern Ireland after 38 years. A total of 300,000 soldiers were deployed as part of “ Operation Banner ”, which began in the wake of the 1969 unrest. At midnight local time, the police resumed sole responsibility for internal security and most of the military personnel were withdrawn.

On November 11, 2007, the Ulster Defense Association (UDA), another major Loyalist paramilitary organization, also announced a formal renunciation of force.

On the night of 7/8 March 2009, two British soldiers were killed in an attack when two unidentified gunmen from a passing car opened fire at the entrance to Massereene Barracks near Antrim , where units of the Corps of Royal Engineers are based . This assassination, which seriously injured two other soldiers and two food delivery men, claimed the lives of British military personnel for the first time since 1997. All parties in the UK and Ireland unanimously condemned the event and feared a renewed spiral of violence. The Republican splinter group Real IRA claimed responsibility for the assassination in a call to a local Irish newspaper . Two days later, the Continuity IRA shot and killed a police officer.

On April 2, 2011, a 25-year-old police officer died in a bomb attack in the northern Irish city of Omagh. The explosive device exploded under the car of one of his family members.

On June 21 and 22, 2011, the worst riots in years took place in Belfast between around 700 violent criminals, most of whom were young people, from both denominations and the police, during which several people were injured. Objects such as stones, firecrackers and Molotov cocktails were thrown; three pistol shots were also fired (one of which injured a police officer).

On July 26, 2012, the day before the opening of the Summer Olympics, various factions announced the re-establishment of the IRA.

Bloody clashes broke out between loyalists and nationalists in Belfast around 4 January 2013 after the Republican-dominated City Council decided that the British flag should no longer be flown year-round over City Hall, but only on the 17th symbolic days.

Government Crisis 2015

On August 12, 2015, Kevin McGuigan, a former senior member of the Provisional IRA (PIRA), was shot dead by unidentified gunmen in Belfast. The murder subsequently escalated into a government crisis. Police of Northern Ireland (PSNI) found that McGuigan had been shot by individual PIRA members, that PIRA continued to exist as an organization albeit no longer as a terrorist organization and that PIRA's senior management did not authorize the killing. On August 30, 2015, the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) announced its exit from the government of Northern Ireland. Party leader Mike Nesbitt stated that if PIRA continued to exist contrary to the terms of the Good Friday Agreement, the UUP could not co-govern with Sinn Féin. The trust has been destroyed. On August 23, Gerry Adams had stated that the IRA no longer existed and that the murders of Kevin McGuigan and Gerard Davison , another former senior Republican, were believed to be unrelated to the IRA.

The Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) has asked British Prime Minister David Cameron to suspend the Northern Ireland Assembly. When this did not happen, Peter Robinson (DUP) resigned as First Minister on 10 September 2015. Three other DUP ministers followed him in this step. The only remaining DUP minister in the government was Arlene Foster , who acted as acting First Minister while also serving as Treasury Secretary. Robinson cited the arrest of Bobby Storey , the chairman of Sinn Féin in Northern Ireland, along with well-known Republicans Brian Gillen and Eddie Copeland on September 9 as a decisive event for his move . Storey is considered the head of intelligence for the PIRA and is a close confidant of Gerry Adams. All three men were released by the police without further conditions the day after their arrest. The DUP said that Arlene Foster's remaining in government gave the party about six weeks to find a solution to the situation.

After 10 weeks of negotiations, Northern Ireland's five main parties reached an agreement on November 17 on a series of controversial plans which Prime Minister David Cameron described as a turning point in Northern Ireland's history and an end to the government crisis. The parties were able to agree that the central government in London would make a payment of £585m to compensate for cuts in welfare benefits affecting the rest of the UK. At the same time, Northern Ireland was allowed to set its own corporate tax rate of 12.5%, aligning it with that of the Republic of Ireland. Furthermore, it was also agreed during the negotiations to entrust a new international group with the task of monitoring the activities of paramilitary organizations and to do more to combat border crime such as petrol smuggling.

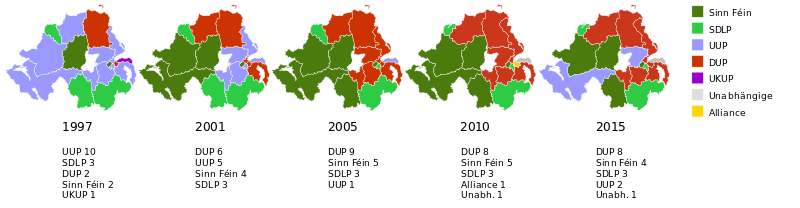

Northern Ireland constituency results in the UK House of Commons elections 1997–2015:

Since 2016, Brexit

In the Brexit referendum , Northern Ireland voted to remain in the EU with a majority of 55.8%. Ireland 's Taoiseach Enda Kenny , the leader of Ireland's largest opposition party , Fianna Fáil , Micheál Martin , and Northern Ireland 's Sinn Féin leader Gerry Adams then hinted at the possibility of a referendum on uniting Northern Ireland with the republic in the south. During the election campaign, Sinn Féin campaigned to remain in the EU; her coalition partner, the Protestant Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), on the other hand, advocated leaving the EU. DUP leader Arlene Foster described the exit as the start of great opportunities for Northern Ireland and the UK as a whole.

In March 2016, the Northern Ireland Department for Economic Affairs calculated the risks of a Brexit with a loss of up to 5.6% of the gross national product . The previous year it put the total of EU aid received from 2007 to 2013 at £2.4 billion and said further EU aid to Northern Ireland was urgently needed.

At the beginning of February 2019, shortly before the United Kingdom planned to leave the EU , Sinn Féin boss Mary Lou McDonald called for the reunification referendum provided for in the Good Friday Agreement to be held. She reminded that the people of Northern Ireland did not vote for Brexit and certainly not for a hard border with Ireland. However, this vote was ignored by the British government in London, which does not care about the local people.

On January 19, 2019, a car bomb exploded in front of the courthouse in the Northern Irish city of Londonderry/Derry. The British police arrested two suspects the following day and blamed the RIRA or the "New IRA", which had emerged from it in 2012, for the attack.

The journalist Lyra McKee was shot and died in hospital during serious riots between demonstrators and the police on April 18, 2019 in the Northern Irish city of Londonderry/Derry . The New IRA claimed responsibility for the attack.

In the 2019 General Election, Republican parties won more seats than Unionists for the first time in history.

conflict parties

Irish nationalist side

The majority of Catholic nationalists strive for a detachment from Great Britain and a union with the Republic of Ireland.

- (Provisional) Irish Republican Army (IRA or PIRA): The most prominent paramilitary organization in Northern Ireland. On July 28, 2005, she declared her armed struggle over. The term "Provisional" refers to the split in the IRA at the outbreak of the civil war in 1969; the other wing is referred to as the Official Irish Republican Army (OIRA).

- Sinn Féin : Your name means “we ourselves”. It is considered the political arm of the IRA. The best-known member of the party is Gerry Adams .

- Irish Republican Socialist Party (IRSP) / Irish National Liberation Army (INLA): Socialist party that emerged from OIRA in 1975 and its armed wing. In 2009, after a 12-year ceasefire, INLA declared the definitive end of its armed struggle.

- Republican Sinn Féin / Continuity IRA (CIRA): Departed from PIRA in 1986. Not in truce.

- 32 County Sovereignty Movement / Real IRA (RIRA): Formed 1997. Not in truce.

- Republican Action Against Drugs : Joining Other Splinter Groups on the New IRA (2012). Not in the truce.

- The Social Democratic and Labor Party (SDLP) is a non-violent party peacefully seeking the unification of Northern Ireland with the Republic of Ireland.

Unionist-Loyalist side

The majority Protestant Unionists want to remain part of the British Kingdom.

- Ulster Unionist Party (UUP): Major political party . The best-known member of the party is David Trimble .

- Democratic Unionist Party (DUP): Protestant Unionist political party that long did not support the Good Friday Agreement. The best-known member of this party was the vicar Ian Paisley .

- Ulster Defense Association (UDA): The main Protestant paramilitary group, disarmed since 2010.

- Ulster Freedom Fighter (UFF): Since the UDA was a legal organization for a long time, it used the combat name UFF for assassination attempts. Some of the units became independent at times.

- Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF): The second Protestant paramilitary organization.

Northern Irish Security Forces

The nationalist camp always saw the Northern Irish security forces as an active party to the conflict and not as a neutral force responsible for maintaining order. Particularly noteworthy here are the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI), formerly the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) with its associated paramilitary auxiliary force, the Ulster Special Constabulary , and the Ulster Defense Regiment (UDR), which emerged from the Ulster Special Constabulary . Since the mid-1980s, a number of official investigations, such as the Stevens Report 2003, have shown that direct cooperation between security forces and loyalist death squads had repeatedly occurred. Agents cooperating with the British military also committed murders of suspected IRA sympathizers, such as the lawyer Patrick Finucane in 1989. Therefore the approach of the Protestant/British side has been described in part as the Dirty War .

neutral parties to the conflict

The Alliance Party of Northern Ireland is the only party that regards the conflict as a central political point, but feels that it does not belong to any side and is acting in a non -denominational manner. Their goals are the peaceful coexistence of all residents of Northern Ireland and a political solution for the region that is fair to everyone.

British government

The UK Government's Northern Ireland Ministers govern Northern Ireland when it is unable to do so.

Republic of Ireland

The aim of union with Northern Ireland was enshrined in the constitution . As part of the Good Friday Agreement, Ireland renounced this claim after a referendum ; the passage has been deleted. However, the Good Friday Agreement expressly leaves open the possibility of reunification with the Republic of Ireland if a majority of Northern Ireland votes in favour. So far this has not been the case.

See also

literature

- T Ryle Dwyer: Michael Collins. Biography. Unrast, Munster 1997, ISBN 3-928300-62-8 . (German).

- Michael Collins : The Path to Freedom . Mercier Press, ISBN 1-85635-148-3 (English).

- Dietrich Schulze-Marmeling (ed.): Northern Ireland - History Landscape Culture & Tours . The workshop, Goettingen 1996, ISBN 3-89533-177-5 .

- Pit Wuhrer: The Drums of Drumcree. Northern Ireland on the Edge of Peace . Rotpunktverlag, 2000, ISBN 3-85869-209-3 .

- Danny Morrison : Out of the Maze. Writings on the Road to Peace in Northern Ireland. Unrast, Munster 1999, ISBN 3-89771-000-5 .

- Kevin Bean, Mark Hayes (eds.): Republican Voices. Voices from the Irish Republican Movement. Unrast, Munster 2002, ISBN 3-89771-011-0 . (Interviews with former members; German).

- Frank Otto: The Northern Ireland Conflict. Origin, History, Perspectives . Verlag CH Beck, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-406-52806-6 .

- Brian A. Jackson: Counterinsurgency Intelligence in a "Long War": the British experience in Northern Ireland (PDF, 13 p.; 648 kB), RAND Corporation , In: MILITARY REVIEW, January-February 2007, pp. 74–85.

- Robert McLiam Wilson: Eureka Street, Belfast. Novel. Fischer Paperback Publishing House, Frankfurt am Main 2008, ISBN 3-596-14416-7 .

movies

- Familiar Enemy ; Director: Alan J. Pakula (USA 1997)

- Ireland ; two-part documentary by Emmanuel Hamon for Arte (France 2015)

- '71: Behind Enemy Lines ; Director: Yann Demange (UK 2014)

web links

- Informative site with a detailed collection of links

- Conflict Archive on the Internet - very extensive site of the University of Ulster (English)

- Images of the Northern Ireland conflict - extensive photo collection, especially murals

- BBC – History : The Northern Ireland Conflict

itemizations

- ↑ www.tagesspiegel.de: Why the tensions in Northern Ireland are so dangerous , April 19, 2019.

- ↑ Abstracts on Organizations – 'U'

- ↑ Peter Taylor: Loyalists . Bloomsbury Publishing, 1999, ISBN 0-7475-4519-7 , pp. 37-40 .

- ↑ Peter Taylor, Loyalists , pp. 41-44.

- ↑ Peter Taylor, Loyalists , pp. 59-60.

- ↑ The Derry March , accessed 4 October 2018.

- ↑ Cameron Report , paragraphs 37-55

- ↑ "We Shall Overcome" ... The History of the Struggle for Civil Rights in Northern Ireland 1968-1978 , accessed 4 October 2018.

- ↑ Lost Lives 2007 edition, ISBN 978-1-84018-504-1 .

- ↑ About turn ( Memento of August 28, 2007 at the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Peter Taylor: Provos The IRA & Sinn Fein . Bloomsbury Publishing, 1998, ISBN 0-7475-3392-X , pp. 77-78 .

- ↑ Patrick Bishop, Eamonn Mallie: The Provisional IRA . Corgi Books, 1997, p. 182 .

- ↑ Patrick Bishop, Eamonn Mallie: The Provisional IRA , p. 188.

- ↑ List of Deaths

- ↑ Patrick Bishop, Eamonn Mallie: The Provisional IRA , p. 192.

- ↑ Peter Taylor, Provos The IRA & Sinn Féin , p. 139.

- ↑ Ed Moloney: A Secret History of the IRA . Penguin, 2003, ISBN 0-14-102876-9 , pp 116 .

- ↑ Patrick Bishop, Eamonn Mallie: The Provisional IRA , p. 247.

- ↑ cain.ulst.ac.uk (English).

- ↑ ab Kevin Kelley: The Longest War: Northern Ireland and the IRA . Lawrence Hill & Co, 1988, ISBN 0-88208-149-7 , pp. 233-241 .

- ↑ Kevin Kelley, The Longest War: Northern Ireland and the IRA. pp. 241-265.

- ↑ Brendan O'Brien, The Long War: The IRA and Sinn Fein . O'Brien Press Ltd, 1999, ISBN 0-86278-606-1 , pp 127 .

- ↑ Irish EU Presidency 2013 : Ireland & The Presidency. About Ireland. Irish Politics and Government. Northern Ireland . Online at www.eu2013.ie. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- ↑ John Campbell: Margaret Thatcher. Volume Two: The Iron Lady . Vintage Books, London 2008, p. 436.

- ↑ David McKittrick, Northern Ireland: The longest tour of duty is over ( memento of 9 August 2007 at the Internet Archive ), The Independent , 31 July 2007.

- ↑ https://books.google.de/books?id=B0Djz3Aq_7IC&pg=PA75&lpg=PA75&dq=Ulster+Defence+Association+++11+November+2007&source=bl&ots=kEeLPeySfv&sig=ACfU3U0B7RFlg_15A-qwTsZWtITrbqkBmA&hl=de&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjAvNzHiKTqAhWQyKYKHSUACcUQ6AEwDHoECAwQAQ#v =onepage&q=Ulster%20Defence%20Association%20%20%2011%20November%202007&f=false

- ↑ See o.v.: Two die in 'barbaric' Army attack , in: BBC Online , 8 March 2009. Accessed 8 March 2009.

- ↑ Untitled : How the barracks attack unfolded , in: BBC Online , 8 March 2009. Accessed 8 March 2009.

- ↑ See Antrim shooting: Political reaction , in: BBC Online , 8 March 2009. Accessed 8 March 2009.

- ↑ Real IRA was behind army attack . BBC. March 8, 2009. Retrieved March 8, 2009.

- ^ Booth, Jenny, Continuity IRA claims murder of police officer in Northern Ireland , in Times Online , 8 March 2009. Accessed 8 March 2009.

- ↑ www.spiegel.de

- ↑ www.theguardian.com (English).

- ↑ Northern Ireland: 18 injured in British flag riot , Spiegel Online, retrieved 5 February 2013.

- ↑ PSNI: Provisional IRA leadership did not sanction Kevin McGuigan murder in The Guardian, 22 August 2015, accessed 11 September 2015.

- ↑ Sinn Féin's Gerry Adams says IRA 'has gone away'. BBC News 23 August 2015, retrieved 11 September 2015 (English): 'Sinn Féin President Gerry Adams has said there is no reason for armed republican groups to exist as the movement is committed to peace. And he said individuals involved in the recent murders of ex-IRA men Gerard 'Jock' Davison and Kevin McGuigan Sr “do not represent republicanism”. He added: “They are not the IRA. The IRA has gone away, you know."

- ↑ Martin McGuinness denounces arrest of Sinn Féin colleague. The Guardian, 9 September 2015, accessed 11 September 2015 (English).

- ^ a b Stormont in crisis as Northern Ireland's first minister Peter Robinson resigns. The Guardian, 10 September 2015, accessed 11 September 2015 (English).

- ↑ NI first minister Peter Robinson steps aside in Stormont crisis. BBC News, 10 September 2015, accessed 10 September 2015 (English).

- ↑ Henry McDonald Northern Ireland power sharing saved in The Guardian, 17 November 2015, accessed 18 November 2015.

- ↑ Border poll: Enda Kenny 'Brexit talks must consider possibility' , BBC News, 18 July 2016

- ↑ Fianna Fail's Micheal Martin hoping Brexit will bring reunification closer , Belfast Telegraph, 17 July 2016

- ^ a b Gerry Adams maintains unity vote stance despite Brokenshire remarks , Belfast Telegraph, 18 July 2016

- ↑ Brexit is the beginning of the end for Northern Ireland , Kevin Meagher, New Statesman , 27 July 2016

- ↑ https://www.independent.ie/irish-news/news/regardless-of-brexit-there-will-be-a-unity-referendum-mary-lou-mcdonald-calls-for-a-vote-on -irish-unity-37776122.html

- ↑ https://www.independent.ie/irish-news/news/regardless-of-brexit-there-will-be-a-unity-referendum-mary-lou-mcdonald-calls-for-a-vote-on -irish-unity-37776122.html

- ↑ news.bbc.co.uk (English).

- ^ a b cryptome.org .

- ↑ Martin Dillon, The Dirty War: Covert Strategies and Tactics Used in Political Conflicts . Routledge, 1999, ISBN 0-415-92281-X .

- ↑ Britain's dirty war; Northern Ireland. (Security forces and murder in Northern Ireland). (No longer available online.) In: The Economist. April 26, 2003, archived from the original on May 13, 2013 ; retrieved January 9, 2009 .