Altenberger Pinge

The Altenberger Pinge (also Altenberger Binge ) is a pinge created by mining on tin stone in Altenberg in the Eastern Ore Mountains . The main break occurred in 1620. At the beginning of the 19th century, the Pinge only had an area of about 2.5 hectares . From about 1976 in particular, it was significantly expanded through intensive ore mining . Today it has an average diameter of 400 m, a depth of about 130 m and an area of about 12 hectares.

The Pinge and some of the associated mining facilities are part of the UNESCO World Heritage Site of the Ore Mountains Mining Region . In 2006 it was named one of the 77 most important national geotopes .

location and size

The Pinge is located on the outskirts of Altenberg; some houses are only 50 m away. Today it has a diameter of about 440 m in the northwest-southeast direction and about 380 m diagonally to it. The depth is about 120 to 150 m.

geology

The origin of the Altenberg tin deposit is related to volcanic activity in the Upper Carboniferous about 300 million years ago. Between Teplice ( Teplitz ) and Dippoldiswalde a 26 km long, 8 km wide and NNW-SSE-running fault zone developed. In this fissure zone, there were numerous magma surges, some of which were pyroclastic . In the Altenberg area, a tin granite got stuck between older granites and quartz porphyries , some of which also had increased tin contents . After feldspar, quartz and mica had crystallized out, the feldspars were decomposed pneumatolytically to quartz and mica by the hot, pressurized vapors and solutions . Tiny grains of tin stone formed in this “quartzized” granite, the so-called old man . This hybrid - half rock, half ore - was the subject of mining. Enrichments in corridors were rare. A special feature was formed Pyknit , a stängliger topaz.

Compared to other deposits, the tin content was rather low, but constant, so that long-term planning could be made. Shortly before mining was stopped, the average tin content was given as 0.36%. Below a depth of around 200 to 220 m , the building quality decreases rapidly.

Emergence

Prehistory (until 1545)

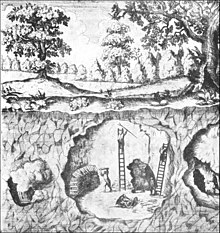

While before 1440 only tin barley was extracted from soaps , underground mining started around 1440 , which initially remained close to the surface. The finds led to a mountain scream that attracted numerous miners from Saxony and Bohemia and led to the rapid growth of the settlement. In 1446 the Saxon Elector Friedrich II bought parts of the area and in 1451 granted the settlement “off dem geyßingißberg” town and market rights . One penetrated quickly into depths of up to 200 m. The preferred method of mining was setting fire , which caused the rock to become brittle. Rounded widening structures with a diameter of 3 to 20 m formed underground . Göpels were used to move the ore upwards. Between 1452 and 1458 the 7.4 km long was Aschergraben created, the impact of water for the numerous stamp mills approach resulted in which the ore was crushed. Around 1480, around 3,000 miners were working in Altenberg. To improve the dewatering , Elector Friedrich the Wise established the 1978 m long Zwitterstock deep Erbstolln including funding from the cities of Freiberg, Dresden and Leipzig as well as the cathedral hospitals and monasteries of Freiberg, Meißen and Altzella . Between 1491 and 1543, the tunnel was driven in the opposite direction towards Rotes Wasser , a tributary of the Müglitz , north of Geising and came in at a depth of 132.7 m below the Roman shaft. The union established for this could now demand the ninth from the mines. From then on, the water only had to be raised to this first level (585 to 590 m above sea level).

Ping fractures (1545-1620)

As early as November 15, 1545, the first small daybreak occurred , in which a woman, her child and six workers were killed. A total of ten mines were affected. The mining was not interrupted by this and Reyer even suspects a transport, as the extraction of the broken material helped save expensive firewood. In order to lift the water out of the buildings below the Erbstollen, new water arts were required. Subsequently, the small and large gallows pond were created and the water was brought in via Neugraben and Quergraben . This impact water operated two artificial wheels . The new art, which replaced 160 water servants, was put into operation in 1554. The intensity of mining is z. B. expressed by the fact that in 1576 there were 124 mine fields on an area of 5 hectares.

On April 22, 1578, other parts of the mine collapsed. This time four mines were affected. It was suspected that "the shafts [for easier extraction] were deliberately made to go". Although the responsible mining officials were relieved of their posts, the overexploitation continued unchanged. Larger, underground fractures occurred in 1583/1587 and on March 10 and December 1, 1619.

On January 24, 1620 between 4 and 5 a.m., the main break occurred. The damage and impact were immense. Graupener Zeche, Rietzschels Zeche, Herrenzeche and Schellenzeche sank together with their Göpeln. Likewise the beer mouth shaft as well as the mountain blacksmith's house and facilities . 24 people were buried, of which 19 were rescued on the same day and 4 more on the fourth day. One person, however, remained buried, who was later blamed for the accident, since this "should have particularly advised to cut away the mountain forts". 79-year-old David Eichler was never found. (1) The tremors could be felt in Dresden, more than 30 km away. The pinge now had an area of 3500 square fathoms, or about 15100 m² (1.5 hectares), which corresponds to a diameter of about 140 m.

Stagnation (1620–1663)

The Pingenbruch and the Thirty Years' War , which also hit the Ore Mountains from 1631, brought mining to an almost complete standstill. Already in 1613 things were no longer good for the Altenberg mining industry. Then in 1620 the ping broke followed. In 1623 there were strikes due to price increases, in 1632 Holk attacked Altenberg, in 1633 the plague raged, in 1636 the first additional penalties had to be paid. Extraction was only possible in the peripheral areas and in 1638 mining came to a complete standstill. In 1639 the Swedish troops destroyed many mining facilities. In 1633, 1648 and 1653 the Erbstolln also collapsed. The water rose up to 80 m above the tunnel sole. It was not until 1660 took place the workover and the water needed afterwards two years to drain.

Quarry mining by the Zwitterstocks union (1663-1850)

Under Balthasar Rösler , mining started up again from 1663. The numerous small mines could not cope with the problems on their own and on August 4, 1663 the "Union of the Zwitterstocks zu Altenberg" was formed. This not only belonged to the mine, but also 26 stamp mills , 5 artificial ponds , the Aschergraben, forests and, from 1697, the Schmiedeberg manor . In 1686 an artificial bike was installed at the Saustaller Schacht so that the bottom below the Erbstollen could be built again. The Roman shaft to the south was sunk between 1837 and 1850, which enabled a significant increase in production. In 1845 the fire- setting was finally stopped and the shovel dismantling that had been practiced since the middle of the 17th century became more and more popular.

But even during this period there were repeated uncontrolled breaks, for example in 1688, 1714, 1716, 1776 (Peptöpfer shaft destroyed), 1785, 1817 (thus all shafts in the Pingen area were destroyed), 1829 and 1844. The chronicle of 1747 records numerous Dead from dangerous mining.

Another stagnation (1850-1930)

As a result, however, there was another decline. The abolition of the principle of direction in the Saxon mining industry (1868), d. H. the enforcement of capitalist principles and extensive tin imports since 1870 led to a drop in prices. Yield was paid for the last time in 1872 . In 1877 the mine was named “United Field in Zwitterstock” under commercial law, in 1889 the “Altenberger Zwitterstock Union” was re-established, and finally on November 1, 1890, the Zwitterstock union was consolidated with the formerly independent Erbstolln union. Government grants and rising tin prices since 1894 helped through the Depression . But the extraction methods have also been improved. In the beginning, the extraction site was driven into the broken masses by means of gear timbering, but in the 20th century the mining methods were more and more adapted to the conditions, on the one hand to reduce the dangers of falling broken masses and on the other hand to increase performance. Not only the global economic crisis , but also since 1908 complaints from paper and cardboard factories due to contamination of the Müglitz water led to the ordered closure in 1930.

Resumption after 1934

In April 1934, the water disputes were settled and tin production resumed, as the Nazi regime was striving for self-sufficiency here . Numerous technical improvements were made. In 1934 an electric hoist was installed in the Römerschacht and a sedimentation basin was set up in the Tiefenbach valley . In 1937, the black water treatment was put into operation and the smelting of the fine tin relocated to Freiberg. In 1942, an armaments factory of the Sachsenwerk Dresden-Niedersedlitz was built into the Heinrichssohle . For the purpose of further concentration, the Zwitterstock AG was merged with the Sachsenz Bergwerksgesellschaft mbH and four other state-owned mining operations on September 22, 1944, retrospectively from April 1, 1944, to form Sachsz Bergwerks AG .

Resumption after 1946

After the Second World War, the black water treatment and parts of the Römerschacht were dismantled as a reparation payment , but the reconstruction began in 1946 and production started again in October 1946. On January 1, 1951, VEB Zinnerz Altenberg was founded and as a result, an intensive expansion of the company began. Between 1952 and 1963 the Arno-Lippmann-Schacht was sunk as a new main shaft to a depth of 296.7 m. Shaft III (260.4 m) served to relieve the main shaft. In 1967 VEB Zinnerz was integrated into the mining and smelting combine "Albert Funk" . The dismantling of the pushing site was further perfected and in the 1970s almost 50 tons per man and shift were achieved. In 1982 the last Schubort was also closed. This meant that the Roman shaft, which was only used for ventilation , had its day. From now on, extraction took place in loading points in the chamber pillar quarry , after having gained experience with this since 1976. The shift performance increased to up to 180 tons per man.

On March 28, 1991, after 550 years of mining, the last hunt was symbolically promoted and tin mining was discontinued, as cost costs and world market prices have been developing strongly in opposite directions since the mid-1980s. During this time 32 million tons of ore were mined, which resulted in an average grade of about 0.76% about 240,000 tons of crude tin. About 106,000 tons of pure tin were obtained from this, so that the output was about 44%.

The proven remaining supplies amount to 74,200 tons of tin.

tourism

The pinge is fenced and cannot be walked on. Between 1928 and 1942 as well as 1949 and 1953, the 85 m deep Heinrichssohle with its fire-set extensions could be visited. A mining nature trail goes around the pinge and a guided hike can be used to gain a deeper insight from a platform. In addition, Pinge Station No. 34 is on the cross-border German-Czech mining trail .

Remarks

literature

- Christoph Meißner : Cumbersome news from the Churfl. Saxon. The town of Altenberg, situated in the town of tin mountain, in Meissen on the Bohemian border, together with the associated diplomatic bus, and an appendix from the neighboring towns and mountain regions . Harpeter, Dresden, Leipzig 1747 ( digitized version ).

- Eduard Reyer : About the ore-bearing deep eruptions of Zinnwald-Altenberg and about the tin mining in this area . 1879, p. 1–60, 5 plates ( PDF on ZOBODAT ).

- Otto Trautmann: The Altenberger Binge . Documents on Saxon and southern German economic history. In: New archive for Saxon history and antiquity . tape 47 , 1926, pp. 204-236 ( digitized version ).

- Altenberg. e) binge. In: Around Altenberg, Geising and Lauenstein (= values of the German homeland . Volume 7). 1st edition. Akademie Verlag, Berlin 1964, pp. 101-105.

- Otfried Wagenbreth et al .: Mining in the Ore Mountains . Technical monuments and history. Ed .: Otfried Wagenbreth, Eberhard Wächtler . 1st edition. German publishing house for basic industry, Leipzig 1990, ISBN 3-342-00509-2 , The mining of Altenberg, Zinnwald and Sadisdorf, p. 157-188 .

- Ludwig Baumann, Ewald Kuschka, Thomas Seifert: Deposits of the Ore Mountains . 1st edition. Enke im Thieme-Verlag, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-13-118281-4 , 4.3 Altenberg deposit district, p. 118-128 .

- Günter Weinhold: The tin ore deposit Altenberg / Osterzgebirge . In: Saxon State Office for Environment and Geology (Hrsg.): Mining in Saxony . tape 9 , 2002 ( PDF files for download and online ).

Individual evidence

- ^ Academy of Geosciences in Hanover eV; Ernst-Rüdiger Look, Horst Quade (Ed.): Fascination Geology. The most important geotopes in Germany. 2nd revised edition. Schweizerbart, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-510-65221-1 .

- ↑ Baumann et al., 2000, p. 119.

- ↑ G. Weinhold, 2002, p. 228.

- ↑ G. Weinhold, 2002, p. 162.

- ^ Adolf Hanle: Geisingberg and Altenberger Pinge . In: Erzgebirge (= Meyer's nature guide ). Meyers Lexikonverlag, Mannheim a. a. 1992, p. 48 .

- ↑ a b c d G. Weinhold, 2002, p. 14.

- ↑ Ch. Meißner, 1747, p. 417.

- ↑ E. Reyer, 1879, p. 42.

- ↑ Ch. Meißner, 1747, p. 76.

- ↑ a b O. Wagenbreth et al., 1990, p. 160.

- ↑ Ch. Meißner, 1747, p. 428.

- ↑ E. Reyer, 1879, p. 43.

- ↑ E. Reyer, 1879, p. 44.

- ↑ G. Weinhold, 2002, p. 17.

- ↑ O. Wagenbreth et al., 1990, p. 161.

- ↑ Inventory 40105 Sachsenz Bergwerks GmbH / AG. Detailed introduction , accessed November 10, 2015

- ↑ G. Weinhold, 2002, p. 163.

- ↑ G. Weinhold, 2002, p. 166.

- ↑ G. Weinhold, 2002, p. 236.

- ↑ G. Weinhold, 2002, p. 239.

- ↑ G. Weinhold, 2002, p. 229.

- ↑ G. Weinhold, 2002, p. 230.

- ↑ Pit rooms on the Heinrichssohle in Altenberg's tin mine , accessed on November 7, 2015

- ↑ Pingen hike on the mining nature trail , accessed on November 7, 2015

- ↑ Cross-border mining educational trail , accessed on November 7, 2015

- ↑ Ch. Meißner, 1747, p. 432.

- ↑ Ch. Meißner, 1747, p. 435.

- ↑ Ch. Meißner, 1747, p. 77.

Web links

- The burglar funnel »Altenberger Pinge« , site of the Saxon State Ministry for Environment and Agriculture

- Holdings 40139 VEB Zinnerz Altenberg and its predecessor in the Freiberg mountain archive

Coordinates: 50 ° 45 ′ 57 ″ N , 13 ° 45 ′ 50 ″ E