Caspar Schmalkalden

Caspar Schmalkalden (* 1616 in Friedrichroda , Duchy of Saxe-Weimar ; † 1673 in Gotha , Duchy of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg ) traveled to South America and the East Indies as a soldier in Dutch service in the 17th century . After his return in 1652, Schmalkalden wrote a travel report of almost 500 handwritten pages in which he noted geographical and ethnological observations as well as descriptions of the flora and fauna of the countries he visited. Despite the extensive information given here, the exact background of his travels is not known. Schmalkalden's account fits into a number of similar writings by travelers of the 17th century. Although he could not serve with new discoveries from a European perspective, his notes offer a valuable addition to the contemporary historical sources.

Life

origin

Caspar Schmalkalden's exact year of birth is not known. When he joined the Dutch army, he was around twenty-five years old, so he was probably born around 1617 or shortly before that. Schmalkalden's father, Liborius Schmalkalden, was mayor of the small town Friedrichroda on the edge of the Thuringian Forest . In the earliest surviving soul register the Protestant church of St. Blaise in Friedrichroda from the year 1632, the mention begins his person. The register also shows that his mother, Magdalena Schmalkalden, also had the sons Christophorus and Liborius and the daughters Anna, Dorothea, Martha and Susanna.

The First Voyage - Brazil and Chile (1642–1645)

Crossing to Brazil

It is not known how Caspar Schmalkalden entered the service of the Dutch West India Company as a soldier . In order to drive their expansion overseas, the Dutch had to resort to seafarers, soldiers, surgeons and other skilled workers from other countries. Schmalkalden mentions, among other things, a comrade who was a “ Scottish ”, his commander on the first trip was “ Churland ”.

On October 16, 1642, Schmalkalden boarded the merchant ship Elephant with 36 other soldiers and four women on the island of Texel . Texel was then the starting point for numerous shipping routes to the Dutch colonies . The ship went under sail on November 4th. The original 97 ships that made up the fleet gradually separated, and only three of them eventually headed for Brazil . Two days after crossing the equator on December 6th, the travelers saw the island of Fernando de Noronha and finally reached the mainland on December 11th. A day later, Schmalkalden and the other soldiers went ashore in Pernambuco .

Stay in Dutch Brazil and expedition to Chile

The colony of New Holland (or Dutch Brazil ) was founded in 1630 by the Dutch West India Company . In July 1642 the Dutch had signed a ten-year armistice with Portugal , so that there was no fighting in this area for the time being, but at the same time the Dutch were deprived of the possibility of further expansion in Brazil. New opportunities were therefore sought in the south-west of the continent, and the experienced Admiral Hendrik Brouwer was sent to Chile to enter into secret trade agreements . He set out on January 12, 1643 with a fleet of five ships. Caspar Schmalkalden was also on the vice admiral ship Vlyssingen .

After the fleet had circled Cape Horn , the travelers sighted Chile for the first time on April 28th and landed on the island of Chiloé on May 10th . On May 20th there was an armed conflict with the Spaniards . The Dutch negotiators managed to negotiate an assistance pact against the Spaniards with the locals. However, when Admiral Hendrik Brouwer died on August 7th and a mutiny by the Dutch soldiers threatened in mid-October because of dwindling rations, the new Admiral Elias Herckmans decided to return to Brazil, which lasted from October 28th to December 29th.

During Schmalkalden's stay in Chile there had been increasing differences in Dutch Brazil between governor Johann Moritz von Nassau-Siegen and the West India Company. Prince Moritz left Brazil in May 1644, after which the colony began to decline. The Portuguese began mobilizing to recapture their colony.

home trip

Caspar Schmalkalden set out on May 27, 1645 with the ship Groningen from Recife to return to Europe. However, the voyage was suddenly interrupted when on June 17, while the fleet was at Paraíba , news came that Cape St. Augustin (about 30 km south of Recife) had been handed over to the Portuguese. Therefore the soldiers - and with them Caspar Schmalkalden - had to go ashore and stayed for a while at Fort Margaretha . The ship Morian was sent ahead to the Netherlands. The predicant (assistant preacher) of the Groningen , Johannes Hasselbeck, traveled ahead with the Morian and appointed Caspar Schmalkalden to be the administrator of his property that remained on the Groningen . The rest of the fleet stayed on the Paraiba until the beginning of July, until an order was received that they should sail to Recife on July 4th. Because of the sea currents running in a northerly direction at this time of year, however, this turned out to be impossible, and instead they headed for the fortress Ceulenburg in the province of Rio Grande do Norte . It took around a month until the news, sent overland from Recife on August 6th, was finally announced that the fleet was allowed to leave for the Netherlands.

On August 7th the ships went under sail. Four days later, Schmalkalden crossed the equator for the second time. At the end of August / beginning of September he crossed the Sargasso Sea (which he called the “Greetings Lake”), in his report he describes the characteristic seaweed that occurs there, which he describes as a salute .

The crossing was not without incident, so Schmalkalden reports the death of a soldier for the night of September 4th, and he writes about September 9th:

- In previous night our Schiffsofficierer had almost all great- and fully drunk together - and was a great commotion and nothing but raping, reviling and rags on the ship, so finally to came down to a fight and lasted until the morning. Then the guilty people were locked up in the boy in the Gallion, and the others went to rest.

In the English Channel the wind was blowing extremely badly, so that one had to anchor near Newport on the Isle of Wight for almost four weeks (from October 13th to November 8th) . When the voyage could finally be resumed, the ship ran into a sandbank when exiting the port and was only able to free itself again after half an hour.

On November 13th, after more than three years absence from the Netherlands, Caspar Schmalkalden reached the city of Groningen and traveled by land to Amsterdam , where he arrived on November 23rd.

The Second Voyage - Java, Taiwan and Japan (1646–1652)

Crossing and stay at the Cape of Good Hope

On April 6, 1646, Caspar Schmalkalden set out from Texel on his second sea voyage, which was to take him around the Cape of Good Hope to the Dutch East Indies . He traveled on the ship King David with a fleet of three other ships. After the fleet had to spend a few weeks in Dover because of the winds , it continued its voyage (after an incident described in detail by Schmalkalden, in which the ship he was on was struck by one of the others and threatened to break apart) in early May .

On May 24th, the travelers passed the Canary Islands . Caspar Schmalkalden reports about Pico del Teide (called Pico Tenerife or Pico de Terraira ): It is considered the highest mountain in the whole world , can be seen sixty miles in the sea, and its peaks are said to be three miles above the Clouds go.

On June 4th they reached the Cape Verde Islands , where they spent six days in Santiago . Schmalkalden reports of frequent conflicts with the predominantly Spanish population, which, according to him, were Spaniards, mostly bandits and frivolous rabble .

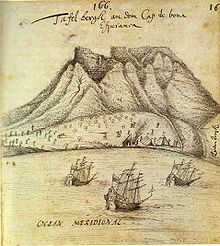

After Schmalkalden had passed the equator for the third time on July 5th, his ship sailed past the Abrolhos (August 8th) and passed Tristan da Cunha on September 5th . On the same day, at the request of the admiral, it was decided that the ship Patientia should sail ahead to India , while the Elephant and King David should give half of their fresh water to the Patientia and land at the Cape of Good Hope . After some debates on board the ships in question, the proposal was adopted unanimously, according to Schmalkalden's report, and on 19 September he went ashore at the Cape of Good Hope (which he called Cabo de Bona Esperanca in Portuguese or Caput bona Spei in Latin ).

During the almost three-week stay in Table Bay , where the city of Cape Town was to be founded six years later , the crews of the two ships lived mainly from bartering with the Khoi Khoi . Among other things, he reports on an incident on September 22nd in which an African was accidentally shot by a Dutch guard (the admiral had expressly forbidden the soldiers to shoot at local residents). Some locals therefore asked the admiral to execute the perpetrator. He feared the end of the barter trade, which was vital for the ship's crews, so he had the soldier in question tied up and brought on board one of the ships and announced that he was to be shot there. The Africans were satisfied with this, but the soldier was soon released.

On September 28, Schmalkalden climbed Table Mountain in a group with seventeen other people , on the summit of which they lit a fire and drank some wine they had brought with them . Schmalkalden was of the opinion that they were the first Europeans to climb the mountain, but in fact it was the Portuguese António de Saldanha more than 140 years earlier (1503) .

Finally, on October 7th, the travelers continued their voyage, saw St. Paul Island on October 31st and reached the Sunda Strait on December 5th . After sighting Sumatra and Krakatau in the following days , they finally went ashore in Batavia on December 11th .

Dutch East Indies

Batavia was founded in 1619 by the Dutch East India Company and quickly developed into the center of all Dutch activities in Asia. Again Schmalkalden left no information about what tasks he had to fulfill here. His stay, however, fell into a relatively peaceful period - there was an armistice between the Portuguese and the Dutch in 1642, and wars did not return until the popular uprisings in 1648 on Ambon and 1650 on Ternate (when Caspar Schmalkalden was in Taiwan and Japan ) Clashes in this region. Schmalkalden had therefore presumably relatively frequent opportunity with the history and presence to occupy the city of Batavia and its inhabitants.

After around seven months in Java, Schmalkalden accompanied the Dutch envoy Joan van Deutecom on a legation trip to Achem ( Aceh ) in the summer of 1647 . He set out from Batavia on July 11 and reached Banda Aceh on August 5 (after a two-day stay in Malacca at the end of July , which at that time had only been under Dutch rule for six years).

On August 22nd the envoy was solemnly received by the Queen of Aceh . An essential part of this reception were animal fights (especially with elephants and buffalos ), which Schmalkalden witnessed as an eyewitness and vividly described.

From August 31st, the Queen received the envoy every week, only the beginning of Lent ( Ramadan ) on September 28th provided an interruption. This lasted for a month, until October 28th, and on November 13th the embassy finally set sail again, so that Schmalkalden returned to Batavia on November 24th.

Taiwan

In 1624 the Dutch landed on the 'Ilha Formosa' ( Taiwan ), discovered by the Portuguese in 1583, and brought the southwestern part of the island under their control by 1641. Their main base, the fortress and settlement Zeelandia, was in the Taiwan Bay (today part of the city of Tainan ), which appears in the Dutch papers as Tayonan , Teiouan , Taiowan etc. in the Dutch papers as well as in Schmalkalden . On April 28, 1648, Schmalkalden set out for Zeelandia on board the Patientia . The journey took him from Batavia to Pulau Laut (one of the Natuna Islands ), Con Dao , the Paracel Islands , the coast of Kochinchina and Hainan . After almost two months, Schmalkalden went ashore in Formosa on June 19.

Shortly thereafter, there was a significant turning point for his future career in the East Indies: On the 27th July I have my gun in the armory passed and I am surveyor been . Schmalkalden remained stationed on Formosa for around two years, dealing with the local geography and culture. On the map attached to his travel description, the parts of the island known to the Dutch are easy to see.

The short period of Dutch rule, which ended in 1661 with the expulsion by Koxinga (Zheng Cheng-Gong), brought a tremendous upheaval for the native tribes. In the course of the Dutch colonization policy, there was a first wave of Chinese immigrants from the mainland. At the same time, the company tried to impose a "civilized" social order on the locals. To do this, they installed a chief in the villages in their sphere of influence, set up schools with Dutch schoolmasters and propagated the Latin alphabet . Schmalkalden's travel book provides some details on this.

Japan

According to the travel book, Schmalkalden set out on June 8, 1650 - after almost two years that he had spent on Formosa - on the Patientia for Japan. Two weeks later, on June 22nd, his ship entered Nagasaki Bay and anchored near the small island of Kisma (Japanese: Tsukishima , artificial island, commonly called Dejima ). Japan had drastically reduced its trade ties around a decade earlier. Only the Dutch were allowed to land among the European nations. With a few exceptions, however, they were not allowed to leave the small Dejima trading post and were subject to various restrictions. The arrival procedures described by Schmalkalden were typical of that time:

- It was announced to all the people of the ship in common to hand over and pack all religious books, ecclesiastical paintings, and European coins. It was also forbidden to commemorate religious matters with the Japonians under physical punishment, much less to let outwardly papist ceremonies be noticed. [...]

- The following day a number of Japanese people, including a Bonjos [= high official] , came on board. They visited everything in the ship, including the pieces, to see whether they were still loaded.

- It also had to announce its name, age and quality man by man, all of which was diligently written down. Finally they locked the ship and this time went ashore again.

Schmalkalden's description of Japan is strikingly short with some information about Nagasaki, Dejima Island and a few remarks about the Japanese . Nor does he mention the purpose or length of his stay at a single word. What is certain is that he then returned to Taiwan. Investigations into the service diaries of the Dejima trading office revealed that the data he provided was incorrect. The Patientia occasionally sailed to Japan, for example in 1648, but not in 1650. For June 8, 1650, the Dejima factory's diary only records the arrival of a Chinese junk . If he had actually sailed to Japan, memory played a trick on him. Surely he only saw Nagasaki as a member of a ship's crew. She was not allowed to leave the ship while the cargo was being unloaded by Japanese coolies under strict supervision. In this case, the stay in the bay lasted only a few weeks. Schmalkalden's atypical drawing of the city from the seaside speaks for this assumption.

Journey home from East India

Caspar Schmalkalden stayed on Formosa until autumn 1651. However, when two ships were due to leave for Batavia at the same time, he decided to put into practice his long-cherished wish to return home. He therefore asked the Dutch governor of the island to be released. He also writes:

- "The same person, when he was looking through my requests, replied that he was surprised that I asked for resignation, since happiness was only now open to me. If I promised myself again, my fee and board should be improved that much again. I thanked him officially and stayed with my resolution, considering that I had long since made a vow that if the good Lord would keep me well in my service for a certain period of time, I would no longer stay in India, but as soon as it would be possible to go back to the fatherland, where the true Christian teaching is being practiced. "

Finally, on October 10, Schmalkalden received the news that his request had been granted and that he should be relieved, which he was delighted to see . After making the necessary preparations for departure, he boarded the ship King David on October 23 .

Almost nothing is known about Caspar Schmalkalden's return trip, since the relevant pages of his report have been lost. It can be seen as certain that he first went to Batavia. Since the crossing from Java to the Netherlands usually took about six months, he probably stayed in Batavia for another four months or even on Mauritius , which was an important supply station for the Dutch on the East India route. It is also possible that he still visited the Spice Islands , as indicated by two surviving images titled Fort Victoria on the island of Amboynan (= Ambon ) and Taluco on the island of Ternate .

Only a section of the report has survived, according to which he called at the island of St. Helena in May 1652 . The team had not entered the Cape of Good Hope (where the Cape Town branch had been founded by Jan van Riebeeck about six weeks earlier ) this time and now poached some horses that were to be abandoned at the Cape of Good Hope on St. Helena .

After the explanations about his stay on St. Helena, Schmalkalden's report finally breaks off. Since the first naval war between the Netherlands and England was in progress at that time , it can be assumed that the fleet circumnavigated the British Isles and instead headed for Norway , from where they then sailed south. The uitloopboek van schepen , which is in the possession of the Imperial Archives in The Hague , shows that King David finally returned to Texel on August 15, 1652.

Further life

After traveling for more than ten years in the service of the Dutch, he returned to his Thuringian homeland, where he settled in Gotha . He gave the ducal art chamber Ernst the Pious a (but insufficiently prepared and therefore not preserved) bellows of the Great Bird of Paradise as well as some self-made compasses and geometric measuring instruments , possibly from his time as a surveyor on Formosa.

Through his activities in the colonies he seems to have made a modest fortune - unlike most of the soldiers deployed overseas at the time. He owned a house on Schwabhäuser Gasse in Gotha .

On January 30, 1655, he married Susanna Christina Kirchberger, the second daughter of Antonius Günther Kirchberger, consistory and canzley administrator and former secretary of the Duke of Saxe-Weimar, in the Gotha city church St. Margarethen . The couple had three children:

- Johann, born on November 9, 1656

- Christian Günther, born on February 19, 1659

- Adolphus Gottfriedus, born on November 18, 1661

The circumstances of Schmalkalden's death are just as unknown as those of his birth. The last mention of his name can be found in the Gotha population registers from 1665 and 1668. In the following population register from 1675 he is no longer mentioned; he died in 1673.

The travel report

manuscript

Caspar Schmalkalden's handwritten travelogue comprises 489 pages of text and contains 128 mostly colored pen drawings . Some pages of the text are missing.

The manuscript is from two different scribes. While the small, delicate handwriting could be identified beyond doubt as the handwriting of Caspar Schmalkalden by comparison with an entry in Schmalkalden's father-in-law Kirchberger from 1665, there has so far been no clear assignment of the other, far more generous handwriting. Wolfgang Joost suspected in 1983 that it could be the handwriting of Schmalkalden's second son Christian Günther.

The writing style of the report is factual and without exaggeration, but still entertaining. Schmalkalden does not use the typical puffy expression of his time and does not report unbelievable adventures and mythical creatures, but is characterized by a very realistic reporting. The personal feelings and thoughts of Schmalkalden take a back seat and play almost no role at all compared to the neutral reporting.

history

Presumably Schmalkalden summarized the notes he had made during the travels into a cohesive travelogue after his return to Thuringia. The source is a book by the Amsterdam philosopher Caspar van Baerle (or Barlaeus), which was considered the standard work on Dutch Brazil and was published in German in 1659. It is not known how long this travelogue remained in the family's possession. The natural scientist Johann Friedrich Blumenbach (1752-1840) bought it in the second half of the 18th century at an auction in Gotha. The manuscript later came into the possession of Duke Ernst II of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg , in whose library at Friedenstein Castle it was officially added on September 14, 1790 (registered under the shelf mark Chart B 533 ).

In 1967 the sheets were restored and cracks were repaired with Japanese paper .

In 1983 the report was first published by Wolfgang Joost under the title Caspar Schmalkalden's wondrous journeys to West and East India . Joost adapted the spelling and punctuation (except for foreign words) to the 1983 standards and also made a few small changes in the lexical area if certain words had undergone a change in meaning over the past 300 years and could no longer be understood in context . He also arranged the sometimes confused chapters chronologically and provided the work with an introduction and an afterword.

In 2002 it was published again with a different design under the title With Compass and Cannons .

content

Caspar Schmalkalden's travel report is structured very regularly:

- First there is a note-like chronology of the course of the journey, in which Schmalkalden records all the important stations and events of the respective journey segment from take-off to landing.

- This is followed by a geographical description of the travel destination, in which Schmalkalden goes into more detail on the nature and culture of the places and regions it visits.

- Schmalkalden then goes into words and pictures on the culture and the external appearance of the indigenous population of his respective place of residence.

- It concludes with descriptions of conspicuous animal and plant species, each with a picture.

However, this order was not strictly adhered to in all sections, in some cases (especially when Schmalkalden visited places where he was only passing through, such as the Cape of Good Hope) only important information on a certain aspect was briefly inserted (in this Case to the population).

Most of Schmalkalden's descriptions are evidence of his own observation, sometimes he inserts appropriate anecdotes for illustration and entertainment on the respective topic, which he only knows and reproduces from hearsay.

In addition to the components mentioned, each chapter concluded with a list of useful expressions in dealing with the respective population; however, they have been omitted from publication.

Geographical descriptions

The descriptions that Caspar Schmalkalden wrote of the places and regions he visited contain descriptions of natural spaces as well as information on buildings as well as on government, administration and cultural features. The information is supplemented by maps and drawings of city, building and landscape views. Here the colonial aspects (administration and defense) are in the foreground.

In some cases (especially with regard to Batavia, whose conquest and subsequent defense by the Dutch he describes in detail) the descriptions of the nature of the destinations visited at the time of Caspar Schmalkalden are also preceded by treatises on the past of the places in question. These refer primarily to the colonial political successes of the Dutch.

Animal and plant descriptions

The animal and plant descriptions by Caspar Schmalkaldens are not scientific descriptions in the modern sense, but rather Schmalkalden tried to describe the living beings seen to the reader as clearly as possible in terms of special characteristics and behavior. He made numerous comparisons with animals and plants known in Europe and also carried out studies himself. He reports on a Mackack ( red howler monkey ): I had one like that at Fort Margarethen and wanted to raise it. But it did not want to eat anything tied up and did nothing but scream that I had to throw it away.

Numerous other formulations testify to personal experience and observation, for example information about the toxicity of certain jellyfish or certain onomatopoeic expressions - he writes about the Ai ( three-toed sloth ): When it is pushed, it screams "III!" Like a kitten , and about the hedgehog fish it says: If you step on it, it screams: "Hulch!"

In the case of numerous plant species and animals (especially fish) he also mentioned the knowledge about edibility. He also described many types of tropical fruits that are well known to today's Europeans, such as water limes ( watermelons ), pineapples , bacobes or pisang ( bananas ) and coques nuts ( coconuts ). All in all, his descriptions of flora and fauna in the section about Brazil are much more extensive than that about the East Indies, since he focused his attention on geographical and cultural aspects in the latter.

Ethnic descriptions

Caspar Schmalkalden's descriptions of peoples are partly shaped by the typical ethnocentrism of that time. The fact that almost all of the peoples he describes were not of the Christian faith is explained by the fact that they know nothing about the true God. Sometimes he tends to generalizations (he summarizes the numerous peoples of Brazil in only two groups, the Brazilians and the Tapoyers ), which, however, can also be viewed more as a product of his time than as a person. Nevertheless, he tries to be as factual as possible and his descriptions of foreign cultures often testify to astonishment rather than rejection. Nevertheless, one can always read out the wish that the backward state of the “less civilized” peoples should soon cease and they should recognize the “true God”.

Characteristic of Schmalkalden's descriptions of peoples are his illustrations of (male and female) representatives of the respective ethnic groups, each of which is described with a four-line verse from the perspective of the respective group of people. For example, when depicting a Brazilian woman, this verse reads:

- As often as my husband travels, I follow him quickly

- Behengt with bag and pack, and with a child,

- On the way back I go ahead, he walks behind,

- So that nothing happens to me, arm with a war rifle.

Schmalkalden always addresses the same aspects in his ethnographic descriptions: position and tasks of men and women in society, religion and customs, eating habits and clothing. In South America he described Brazilians , Tapoyers and Chileans , in Africa Hottentots (Khoi Khoi) and in Asia Javanese , Malay , Sinese , Formosan and Japanese . He devotes a particularly large amount of space to the representation of the Sinesen ( Han Chinese ), whom he got to know extensively in Batavia and on Formosa.

meaning

Although Caspar Schmalkalden did not report anything that was fundamentally new to the Europeans, some parts of his travelogue today offer an important source of the history of individual regions, which is particularly true of Taiwan, but also of Japan. The artistically high quality of his drawings, which provide a realistic picture of the depicted people from that time, is also remarkable.

There were numerous similar reports from visitors to the colonies at the time. In addition to the aforementioned Barlaeus used Schmalkalden especially the Historia Rerum naturalium Brasiliae of Georg Marcgrave as inspiration for his drawings.

Within the German travel literature, Schmalkalden's reports on Dutch Brazil are part of Zacharias Wagner 's book on animals and Michael Hemmersam's West Indian description of the drawing . Schmalkalden's descriptions of East India find parallels in Johann von der Behr , Johann Jacob Merklein and Johann Jacob Saar .

Newer editions

- Caspar Schmalkalden: The wondrous journeys of Caspar Schmalkalden to West and East India 1642-1652. Adapted from a previously unpublished manuscript and edited by Wolfgang Joost , FA Brockhaus Verlag, Leipzig 1983, ISBN 3-325-00204-8 .

- Caspar Schmalkalden: With a compass and cannons. Adventurous journeys to Brazil and the Far East 1642–1652 , Edition Erdmann 2002, ISBN 3-86503-109-9 .

literature

- Wolfgang Joost: The world journeys of Gothaer Caspar Schmalkalden in the 17th century, 1. The journey to the West Indies , in: Gothaer Museumsheft - Abhandlungen undberichte des Naturkundemuseum , 6 (1971), pp. 1–13.

- Wolfgang Joost: About the treatise of the Gotha world traveler Caspar Schmalkalden (1616–1673): “How to find a given place Longitudinem or length” , in: Gothaisches Museums-Jahrbuch , Vol. 7 2004 (2003), pp. 67–78 , published by the Museum for Regional History and Folklore at Schloss Friedenstein, Gotha, Verlag Hain

- Wolfgang Michel : Japan in Caspar Schmalkaldens travel book , in: Dokufutsu Bungaku Kenkyû , No. 35 (Kyushu University Fukuoka, May 1985), pp. 41-84.

- Wolfgang Michel: An early German-Japanese glossary from the 17th century , in: Kairos , No. 24 (1986) pp. 1–26.

- Wolfgang Michel: Schmalkalden, Caspar. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 23, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-428-11204-3 , p. 119 f. ( Digitized version ).

Web links

- Calendar sheet - Caspar Schmalkalden and the United East India Company ( Memento from April 23, 2003 in the Internet Archive )

- Historical travel reports about China and Tibet

Footnotes

- ↑ a b Joost, W. 2003: About the treatise by the Gotha world traveler Caspar Schmalkalden. In: Gothaisches Museums-Jahrbuch 2004, pp. 67–78.

- ↑ Caspar Schmalkalden: The miraculous journeys of Caspar Schmalkalden to West and East India 1642–1652 , FA Brockhaus Verlag, Leipzig 1983, p. 85

- ↑ Caspar Schmalkalden: The miraculous journeys of Caspar Schmalkalden to West and East India 1642–1652 , FA Brockhaus Verlag, Leipzig 1983, p. 88

- ↑ Caspar Schmalkalden: The miraculous journeys of Caspar Schmalkalden to West and East India 1642–1652 , FA Brockhaus Verlag, Leipzig 1983, p. 90

- ↑ Caspar Schmalkalden: The wondrous journeys of Caspar Schmalkalden to West and East India 1642–1652 , FA Brockhaus Verlag, Leipzig 1983, p. 140

- ^ Caspar Schmalkalden: Caspar Schmalkalden's miraculous journeys to West and East India 1642–1652 , FA Brockhaus Verlag, Leipzig 1983, p. 149/150

- ↑ see Michel (1985).

- ↑ Caspar Schmalkalden: The miraculous journeys of Caspar Schmalkalden to West and East India 1642–1652 , FA Brockhaus Verlag, Leipzig 1983, p. 152 f.

- ↑ Caspar Schmalkalden: The miraculous journeys of Caspar Schmalkalden to West and East India 1642–1652 , FA Brockhaus Verlag, Leipzig 1983, p. 58

- ↑ Caspar Schmalkalden: The wondrous journeys of Caspar Schmalkalden to West and East India 1642–1652 , FA Brockhaus Verlag, Leipzig 1983, p. 66

- ↑ Caspar Schmalkalden: The wondrous journeys of Caspar Schmalkalden to West and East India 1642–1652 , FA Brockhaus Verlag, Leipzig 1983, p. 73

- ↑ Caspar Schmalkalden: The wondrous journeys of Caspar Schmalkalden to West and East India 1642–1652 , FA Brockhaus Verlag, Leipzig 1983, p. 15

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Schmalkalden, Caspar |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German soldier in the Dutch service, explorer and travel writer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 1616 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Friedrichroda , Duchy of Saxony-Weimar |

| DATE OF DEATH | 1673 |

| Place of death | Gotha , Duchy of Saxony-Gotha-Altenburg |