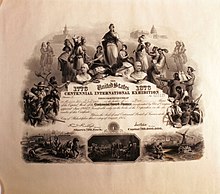

Centennial Exhibition

| Centennial Exhibition 1876 Centennial International Exhibition of Arts, Manufactures and Products of the Soil and Mines |

|

|---|---|

Memorial Hall |

|

| General | |

| Exhibition space | 115 ha |

| new hits |

Telephone sewing machine typewriter Thonet chair |

| Number of visitors | 10.164.489 |

| BIE recognition | Yes |

| participation | |

| countries | 35 countries |

| Exhibitors | 30,864 exhibitors |

| Place of issue | |

| place | Philadelphia |

| terrain | Fairmount Park Coordinates: 39 ° 59 ′ 9.8 " N , 75 ° 12 ′ 22.8" W. |

| calendar | |

| opening | May 10, 1876 |

| closure | November 10, 1876 |

| Chronological order | |

| predecessor | Vienna 1873 |

| successor | Paris 1878 |

The Centennial International Exhibition of 1876 , the first official World's Fair in the United States , was in Philadelphia , Pennsylvania , organized the 100th anniversary of the Independence of the United States to celebrate. The official title of the event was International Exhibition of Arts, Manufactures and Products of the Soil and Mine . It was held in Fairmount Park along the Schuylkill River . The exhibition center was designed by Hermann Schwarzmann.

The exhibition area was 115 hectares . A total of 30,864 exhibitors took part. As innovations were u. a. the Thonet chair , the sewing machine , the typewriter and the telephone were introduced. Around 10 million visitors came to see the exhibition, which at the time would have represented 20% of the population of the United States, had it not been for many multiple visitors.

planning

The idea of the exhibition is attributed to John L. Campbell, a professor of mathematics, natural philosophy and astronomy at Wabash College in Crawfordsville . In December 1866, he made the first proposal to the mayor of Philadelphia to mark the 100th anniversary of the USA with an exhibition. Concerns quickly arose as to whether funding could be guaranteed, whether other nations would participate, or whether the US exhibition contributions could stand up against those of other countries. Despite these concerns, the plan moved forward.

The Franklin Institute sponsored the exhibition early on and asked the Philadelphia City Council to use Fairmount Park. In January 1870, the City Council decided to hold the Centennial Exhibition in the city. The City Council and the Pennsylvania General Assembly (the state assembly of Pennsylvania) formed a committee to work out the project and gain the support of the United States Congress . Representative William D. Kelley spoke on behalf of the city and state, and Daniel Johnson Morrell introduced a bill to set up a United States Jubilee Commission. The law, passed on March 3, 1871, stipulated that the government would not pay any costs.

The commission began its work on March 3, 1872, under the presidency of Joseph R. Hawley of Connecticut . One representative from each state and territory was a member. On June 1, 1872, Congress created a Centennial Board of Finance to secure funding. John Welsh, who had fund raising experience from the Great Sanitary Fair in 1864 , became president. The board was authorized to raise up to $ 10 million through the sale of shares for $ 10. By February 22, 1873 this had raised US $ 1,784,320, Philadelphia contributed $ 1.5 million and Pennsylvania contributed $ 1 million. On February 11, 1876, Congress approved a $ 1.5 million loan. The panel originally considered this to be a subsidy, but after the issue the government sued for the money back. The Supreme Court later followed suit. John Welsh gained the support of the Philadelphia women who had previously helped him at the Great Sanitary Fair. The Women's Centennial Executive Committee was formed with Elizabeth Duane Gillespie, a descendant of Benjamin Franklin , as President. In the first few months, the group raised $ 40,000. When the group learned that the commission barely considered women's work in the exhibition, they raised $ 30,000 for a dedicated women's exhibition building.

In 1873 the commission appointed Alfred T. Goshorn as general director of the exhibition. The Fairmont Park Commission designated 450 acres of West Fairmont Park for the exhibit, dedicated by Secretary of the Navy George M. Robeson on July 4, 1873. Newspaper editor John W. Forney agreed to head and pay a commission from the city that invited other nations in Europe to exhibit. Despite fears of a European boycott and high import duties, all European countries accepted the invitation.

To accommodate visitors to the exhibition, temporary hotels were built near the exhibition center. A special agency drew up a list of hotel rooms, inns, and private accommodations, and then sold tickets for the spaces available in cities promoting the exhibition and on trains going to Philadelphia. More trams were used and the Pennsylvania Railroad deployed special trains from Market Street, New York City , Baltimore and Pittsburgh . The Philadelphia and Reading Railroad also used special trains from Philadelphia's Center City. The exhibition's medical bureau set up a small hospital on the exhibition grounds, but except during a heat wave there were no increased deaths or epidemics.

building

More than 200 buildings were erected on the exhibition grounds, which was surrounded by a fence nearly 3 miles long. The commission organized an architectural competition for the main building. There were two rounds, the winners of the first round had to provide details such as costs and construction time for the final on September 20, 1873. After four winners were chosen, it was found that none of the time and cost constraints met.

The commission turned to the engineers Henry Pettit and Joseph M. Wilson, who took over the construction of the main building. The main building, a temporary structure, was the largest building in the world with a floor plan of 8 hectares. The building was constructed from prefabricated parts in eighteen months. It consisted of wooden and iron frames that rested on 672 stone supports. Glass was used between the frames to let in light. The central corridor was 36.5 m wide, 564.5 m long and 16.7 m high. 25 meter high towers were located on every corner of the building. Exhibits from the United States were placed in the center of the structure, while those from other states were placed around it, depending on the nation's distance from the United States. The main building housed exhibits on mining, metallurgy, assembly , education, and science. The machine hall was to the west of the main building. The machine shop was also designed by Pettit and Wilson and was built similarly, except that the frame was only made of wood. The building, which was erected in six months, was the second largest with a length of 407.3 m and a width of 110 m. On the south side of the building there was a 63.4 × 64.0 m wing. The third largest building was the agricultural hall. Constructed by James Windrim, it was 250 m long and 164.6 m wide. It was made of wood and glass and looked like a number of barns. Agricultural products and machines and related shops were on display.

Unlike most buildings, the horticultural hall was permanently laid out. It was designed by Hermann J. Schwarzmann. Schwarzmann, an engineer with the Fairmont Park Commission, had never designed a building before. The horticultural hall had a frame made of iron and glass, a foundation made of stone and marble and was 116.7 m long, 58.8 m wide and 20.7 m high. It was connected to Fairmont Park by the 155 m long Centennial Monorail . The building was modeled on Moorish architecture and constructed as a tribute to the Crystal Palace of London's Great Exhibition . Horticulture was exhibited in the building; plants continued to be shown after the exhibition until it was badly damaged by Hurricane Hazel in 1954 and then demolished.

The memorial hall was also constructed by Hermann J. Schwarzmann and consists of stone, glass, iron and granite. The building is 111 mx 64 m and 45.7 m high at the highest point, an iron and glass dome. The dome is crowned by a 7 meter high statue of historic Columbia . The memorial hall was constructed in the style of Beaux Arts architecture and housed the art. The exhibition received so many works of art that an extension had to be built. Another building was built for photography. After the exhibition, the memorial hall reopened as the Pennsylvania Museum of the School of Industrial Art in 1877 . In 1928 the school moved to become the Philadelphia Museum of Art . The building continued to exhibit art and was taken over by the Fairmount Park Commission in 1958. Later the building was used as a police station. It was then renovated to house the Please Touch Museum , which opened in 2008.

The British buildings were extensive and showed, among other things, the developed bicycle with tensioned spokes and a large front wheel. Two English manufacturers showed their high bikes ( ordinary bikes or penny farthings ): Bayliss-Thomas and Rudge . These exhibitions motivated Col. Albert Augustus Pope to first import high bikes and then manufacture them in the USA. His Pope Manufacturing Company was the market leader in Columbia bicycles , and after a few years he published Law Bulletin and Good Roads . This was the beginning of the good roads movement of the bicycling fraternity , which from 1903 onwards led to further actions by the American Automobile Association (AAA).

Twenty-six US states had their own buildings, the only remaining building being the Ohio House. Apart from the USA, eleven nations had their own buildings. The US federal government had its own cruciform building with exhibits from various government departments. The women's pavilion was the first building at an international exhibition dedicated to the work of women. The remaining buildings were company buildings, administrative buildings, restaurants and other buildings for the convenience of visitors.

exhibition

The exhibition's formal name was International Exhibition of Arts, Manufactures, and products of the Soil and Mine , but the official theme was the US 100th Anniversary. In addition, the exhibition should show the world the industrial and innovative power of the USA. Originally the exhibition was supposed to open in April on the anniversary of the Battle of Lexington and Concord, but due to construction delays it didn't open until May 10th. Bells were ringing all over Philadelphia. The opening ceremony was attended by US President Ulysses Grant and his wife and by Brazilian Emperor Dom Pedro II and his wife. The ceremony ended in the machine hall, where the two heads of state switched on the Corliss steam engine that supplied most of the other machines with energy. The official number of visitors on the opening day was 186,272, 110,000 of them with free tickets.

In the following days the number of visitors dropped dramatically, with only 12,720 visiting the exhibition. The average for May was 36,000 and 39,000 for June. A heat wave from mid-June to July reduced the number of visitors. The average temperature was 27.2 ° C; the temperature reached 37.8 ° C ten times. The average visit in July was 35,000 and rose to 42,000 in August despite the return of high temperatures towards the end of the month.

Cooling temperatures, news reports and word of mouth increased the number of visitors over the past three months. Many of the visitors came from a great distance. In September the monthly average rose to 94,000 visitors, in October to 102,000. The highest number of visitors was on September 28th. That day, with a quarter of a million visitors, was Pennsylvania Day, a centenary celebration of the Pennsylvania Constitution. There were speeches, receptions and fireworks. November, the last month, had an average of 115,000 visitors. On November 10th, the end of the exhibition, 10,164,489 visitors had visited the exhibition.

Exhibits

Among the technical innovations was, for example, a Corliss steam engine ; the Waltham Watch Company showed the first automatic screw machine and won the gold medal in the first international watch precision competition. Until 2004, many of the exhibits were housed in the Arts and Industries Building of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC. The Turkish delegation showed marijuana for the first time in the US , which became the most visited exhibit at the fair.

The gas engine of George Brayton inspired George B. Selden for the construction of a motor vehicle in 1877; this in turn was evidence in the historical Selden patent dispute .

Among the consumer products shown for the first time were:

- Alexander Graham Bell's phone

- The Remington Typographic Machine ( typewriter )

- Heinz Ketchup ( HJ Heinz Company )

- Thonet chair

- The Wallace-Farmer Electric Dynamo , forerunner of electric light

- Hires Root Beer

The reconstruction of a colonial kitchen , crammed with spinning wheel and costumed actors, led to an era of colonial revival in American architecture and interior design. The Swedish Cottage , a rural Swedish schoolhouse in traditional style, was after the exhibition in Central Park rebuilt in New York. It is now the Swedish Cottage Marionette Theater .

The Cologne chocolate and confectionery manufacturer Ludwig Stollwerck exhibited around 1,000 marzipan items, 200 of which were cakes alone; he received a gold medal for it.

Bremer Beck’s beer won the gold medal for "the best of all continental beers". The image of the medal still appears as a logo on the label today.

A competition that was long felt in the media took place among the predominantly American piano manufacturers . The long-established American piano manufacturers from Chickering & Son and Weber lost to the emerging young competition from German immigrants from Steinway & Sons , who won the gold medal with their newly designed concert grand pianos with full cast iron plates, sound post covers and duplex scales. This win in turn was so controversial in the media - including allegations of corruption and manipulation - that it sparked the “piano wars” that continued to have an impact in the USA for years. The 424 copies of the “ Centennial D Concert Grand ” built from 1875 to 1884 are the original version of the concert grand piano, which is still built in the same way today; the concept of this type of grand piano was copied worldwide and is still today - with only a small change to the case - the model of almost all concert grand pianos since then, with a few exceptions (Blüthner, Bösendorfer). In the end, Steinway & Sons was the undisputed largest and most successful piano manufacturing company not only in the USA; American competition was marginalized. The young Turkish Sultan Abdul Hamid II, newly enthroned in the same year, subsequently became one of Steinway's best private customers; By 1890 he acquired at least six instruments for himself and his harem ladies, including several concert grand pianos.

The New Jersey States Pavilion was a reconstruction of the Ford Mansion , the headquarters of General George Washington during the winter of 1779/1780 in Morristown . The reconstruction showed a functional “colonial kitchen” with an old-fashioned fireplace, which was explained in a polemical story about old-fashioned domesticity . The old-fashioned fireplace and the view of the colonial home were bordered on the theme of progress in order to reinforce the view of American progress, according to which it developed not from the influence of multi-ethnic waves of immigration but from small colonial beginnings.

literature

- Linda P. Gross, Theresa R. Snyder: Philadelphia's 1876 Centennial Exhibition . Arcadia Publishing, 2005, ISBN 0-7385-3888-4 .

- Winfried Kretschmer: History of the world exhibitions . Campus, 1999, ISBN 3-593-36273-2 .

- Erik Mattie: World's Fair . Belser, 1998, ISBN 3-7630-2358-5 .

- Nicholas Wainwright, Russell Weigley, Edwin Wolf: Philadelphia: A 300-Year History . WW Norton & Company, 1982, ISBN 0-393-01610-2 .

- Frank Leslie: The Philadelphia World's Fair 1876. Leslie, New York 1876 digital

Web links

- Centennial Exhibition. Bureau International des Expositions (English). Retrieved March 23, 2017 .

- Centennial Exhibition Digital Collection and web site were developed by the Free Library of Philadelphia.

- JS Ingram: Centennial exposition described and illustrated, being a concise and graphic description of this grand enterprise commemorative of the first centennary of American independence. Hubbard bros, Philadelphia, 1876.

- Frank Leslie: The Philadelphia World's Fair and History of Previous Exhibitions. Published in German.

- The Women's Pavilion. Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia, 1876.

- Prints of Philadelphia - 1876 Centennial Exhibition.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Philadelphia’s 1876 Centennial Exhibition. P. 7.

- ↑ a b Philadelphia: A 300-Year History. P. 460.

- ↑ a b Philadelphia: A 300-Year History. P. 461.

- ^ A b c Philadelphia: A 300-Year History. P. 462.

- ↑ a b Philadelphia: A 300-Year History. Pp. 467-468.

- ↑ a b Philadelphia: A 300-Year History. P. 464.

- ^ Philadelphia's 1876 Centennial Exhibition. Pp 29-30.

- ^ Philadelphia's 1876 Centennial Exhibition. Pp. 85-86.

- ^ Philadelphia's 1876 Centennial Exhibition. P. 95.

- ^ Philadelphia's 1876 Centennial Exhibition. Pp. 101-103.

- ^ Philadelphia's 1876 Centennial Exhibition. P. 105.

- ^ Memorial Hall Update ( February 6, 2007 memento in the Internet Archive ), Please Touch Museum

- ^ Buildings That Need Adoption ( February 24, 2007 memento in the Internet Archive ), Fairmount Park

- ^ Philadelphia's 1876 Centennial Exhibition. P. 109.

- ^ Philadelphia: A 300-Year History. P. 466.

- ^ Richard K. Lieberman: Steinway & Sons. Yale University Press, New Haven / London, pp. 60-72.