Fuji (volcano)

| Fuji | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Fuji from Lake Shōji , with Mount Ōmuro in between |

||

| height | 3776.24 m TP | |

| location | Prefectures Yamanashi and Shizuoka , Japan | |

| Dominance | 2077 km → Xueshan | |

| Notch height | 3776 m | |

| Coordinates | 35 ° 21 '38 " N , 138 ° 43' 38" E | |

|

|

||

| Type | Stratovolcano | |

| Age of the rock | 100,000 years | |

| Last eruption | 1707 | |

| First ascent | Attributed to En-no-Schokaku, c. 700 | |

| Normal way | Mountain tour | |

| particularities | highest mountain in Japan; UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

The Fuji ( Japanese Fuji-san [ ɸɯ (d) ʑisaɴ ]; German: Fudschi ; Duden : Fujiyama , Fudschijama ) is a volcano and at 3776.24 m above sea level the highest mountain in Japan . Its peak is located on the main Japanese island of Honshu on the border between the prefectures of Yamanashi and Shizuoka . It has been part of the world cultural heritage since 2013 .

Geology, geomorphology and eruption history

The Fuji is located in the contact zone of the Eurasian Plate , the Pacific Plate and the Philippines Plate and belongs to the stratovolcanoes (stratovolcanoes) of the Pacific Ring of Fire . It is classified as active with a low risk of an outbreak.

Scientists believe that Fuji was formed in four different sections of volcanic activity: The first section (Sen-komitake) consists of an andesite core deep in the mountain . This was followed by Komitake Fuji , a basalt layer believed to have been formed several hundred thousand years ago. About 100,000 years ago, "ancient Fuji" formed over the surface of Komitake Fuji . Modern, "new" Fuji is believed to have formed over ancient Fuji about 10,000 years ago.

The mountain has erupted eighteen times since records began. The last known eruption occurred in the Edo period on December 16, 1707 and lasted about two weeks. At that time, a second crater and a second peak formed halfway up, named after the name of the era Hōei-zan ( 宝 永 山 ). Today the summit crater is approx. 200 m deep and has a circumference of approx. 2.5 km.

North at the foot of the mountain, in Yamanashi Prefecture , are the five Fuji Lakes .

Surname

etymology

The modern Japanese spelling of Fuji consists of the Kanji 富 ( fu , rich ') 士 ( ji , Warrior') and 山 ( san , Mountain ') together. It can already be found on a wooden tablet ( mokkan ) dated to 735 , which was found in the ruins of the former Heijō Imperial Palace in Nara , as well as in Shoku Nihongi published in 797 . The oldest known spellings are 不盡 ( modern : 不尽 'inexhaustible' ) in the Reichschronik Nihonshoki published in 720 , and 福 慈 'Glück und Affection' from Hitachi Fudoki, compiled between 713 and 721 . In addition to a large number of other spellings, they all have in common that they are only phonograms for the old Japanese name puzi , i.e. H. Chinese characters were used, the Chinese pronunciation of which corresponded to the Japanese ( Man'yōgana ). They therefore do not reflect the actual meaning of the name, which may have long been forgotten by then. It is the same with the spelling enden , which is also still to be found today , which can be represented with “not two”, i.e. “one time”.

The origin of the name is therefore controversial. The best-known Japanese theory leads back to the story of Taketori Monogatari ("The story of the bamboo collector"). In this oldest fairy-tale-romantic story in Japan, the emperor has the potion of immortality destroyed by a large retinue of his warriors on the highest mountain in the country. On the one hand, this should result in the spelling mentioned as "rich in warriors", on the other hand it should also remind of the word for "immortality" ( 不死 , fushi ).

Another well-known theory comes from the British missionary John Batchelor , who researched the Ainu culture ; According to his theory, fuji comes from the Ainu term huci for the goddess of fire Ape-huci-kamuy . The linguist Kindaichi Kyōsuke , however, rejected this for reasons of linguistic history, since the Japanese at that time did not have an h or f initial sound. In addition, huci means 'old woman', while the Ainu term for the fire alluded to in the derivation is ape . An alternative origin from the Ainu, which Batchelor ascribes to the educator Nagata Hōsei (1844–1911), is pus / push , meaning 'break open, break out, (sparks) fly'.

The toponomist Kanji Kagami sees a Japanese origin like the Japanese name of the wisteria fuji as "the name of a mountain foot that hangs down from the sky like a wisteria [...]". This is countered by the fact that both terms were pronounced differently historically: puzi and pudi . There are also dozens of other derivations.

"Fujisan" or "Fujiyama"?

The name Fujiyama (in German-speaking countries, according to Duden, also Fudschi or Fudschijama ) is often used in western cultures and is probably based on a misreading of the character “ 山 ” for mountain. The Japanese Kun reading of this character is yama , but the Sino-Japanese On reading san is used here as a compound of words composed of several characters , not to be confused with the similar-sounding suffix -san in Japanese salutations . The current Japanese pronunciation of the name of the mountain is therefore Fuji-san , although there are also many other Japanese toponyms in which the character “ 山 - mountain” is read as yama . However, in classical Japanese literature, the term Fuji no yama , meaning 'mountain of Fuji' " ふ じ の 山 " , is used as the name for Fuji .

In addition to the linguistic approach, one has to put the historical approach, which provides the insight that the Western name Fujiyama goes back quite obviously to Engelbert Kaempfer, whose description of, first published in London in 1727 posthumously in English and then translated into French, Dutch and even back into German Japan has had a lasting effect on the European image of Japan. Peter K. Kapitza states a "quasi European norm" to which the European image of Japan was brought on the basis of the travel reports received up to then.

While the western travelers to Japan before Kaempfer used the then common name " Fuji no yama " in different spellings, but always with the particle no in the middle - the volume by Kapitza contains six examples from the 17th century . a. also the spelling “Fusi jamma” or “Fusijamma”. The cliché of the “most beautiful mountain in the world Fusi or Fusi no jamma ” can also be found at Kaempfer. Elsewhere Kaempfer gave the name of the volcano with "Fudsi", "Fusji" or "Fusijamma".

In the Edo period, the common name of the volcano Fuji , which was expanded in many ways to Fuji no yama ( ふ じ の や ま , "Mountain of Fuji"), Fuji no mine ( ふ じ の 嶺 , "Summit of Mount Fuji"), Fuji no takane ( ふ じ の 高嶺 , "tip of Mount Fuji") and so on. Since the word yama for "mountain" was widespread and was certainly known to western travelers to Japan, the name Fuji no yama appeared to them the clearest and most understandable and was used alongside the name Fuji in reports from Japan. Since Kaempfer fluctuated between the names Fuji no yama and Fujiyama and omitted the particles no and used them, it seems reasonable to assume that the spelling of Fujiyama goes back to a mistake by Kaempfer. However, one cannot simply rule out that the name Fujiyama also existed in addition to the name Fuji no yama - after all, there is the family name Fujiyama ( 富士山 ), which is spelled exactly like the mountain. In addition, the term Fujiyama - 후시 야마 又云 후 시산 'Fujiyama, also called Fujisan' - can also be found in the Korean-Japanese dictionary W ae-eo yuhae ( 倭 語 類 解 ) from the 1780s.

Incorrect translations of the name as "Mr. Fuji" stem from the fact that the syllables -san ( 山 , mountain ) and -san ( さ ん , neutral Japanese form of address for men and women) are confused with each other.

The most suitable implementation of the name in German is likely to be Fuji . However, some Japanologists are of the opinion that Fujisan can also be used as a proper name, citing, for example, Mont Blanc and Mount Everest , since the foreign word for "mountain" also remains untranslated with those. The syllable -san would be taken as part of the name.

Religious meaning

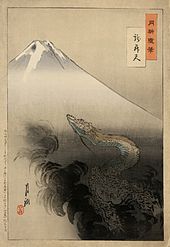

The totality of the religious worship of Fuji is called Fuji shinkō ( 富士 信仰 , Fuji belief ) or Sengen shinkō ( 浅 間 信仰 ).

Fuji has been considered sacred in Shinto for centuries. In order to pacify his outbursts, the imperial court - according to tradition, by Emperor Suinin in 27 BC. BC - the deity Asama no ōkami ( 浅 間 大 神 , also Sengen ōkami , equated with the goddess Konohana-no-sakuya-no-hime ) enthroned and worshiped. In 806, Emperor Heizei ordered the Fujisan Hongū Sengen Taisha Shinto shrine to be built at the foot of the mountain. Today it is the main seat of over 1300 Sengen shrines (also called Asama shrines), which were built at the foot and on the slopes of Mount Fuji to worship it. The shrine area of Okumiya ( 奥 宮 ), a branch of Fujisan Hongū Sengen Taisha , encompasses the entire mountain peak from the 8th station. Fuji is also significant in Japanese Buddhism , especially in its mountain cult form of Shugendō , which sees climbing the mountain as an expression of their faith. In the 12th century, the Buddhist priest Matsudai Schonin built a temple for Sengen Dainichi (the Buddhist deity of the mountain) on the rim of the crater. In addition, the mountain is worshiped by a variety of sects, with the Shugendō-influenced Fuji-kō ( 富士 講 ) founded in the 16th century being the best known.

In the Muromachi period (14th-16th centuries), climbing Mount Fuji became popular, and Buddhist mandalas were created to promote pilgrimages to Mount Fuji. In addition to mountain huts, the Fuji-kō sect also built so-called Fujizuka ("Fuji hill") in and around the capital Edo to enable everyone to symbolically climb the mountain. At the height of this development there were around 200 Fuji hills. In addition, for example, Daimyō also created Fujimizaka ( 富士 見 坂 , "Fuji show hill") in order to be able to view the Fuji better from these elevated points of view. On a clear day the mountain can still be seen from 80–100 km away (also from Yokohama and Tokyo ).

Nearby is the Aokigahara forest , which is famous for its high number of suicides . On February 24, 1926, the " Primeval Forest of Fuji and Aokigahara Forest" ( 富士山 原始 林 及 び 青木 ヶ 原 樹 海 , Fuji-san genshirin oyobi Aokigahara jukai ) were declared a natural monument .

Rockclimbing

There are no written records of when and by whom the mountain was first climbed. The first ascent is attributed to En-no-Schokaku around the year 700. There is a detailed description of the crater from the 9th century. The first ascent by a foreigner was not made until 1860 by Rutherford Alcock . Today, Fuji is one of the most popular tourist destinations in Japan. Thanks to its shape, the mountain is relatively easy to climb compared to other three-thousand-meter peaks . In summer, when the ascent is open to the public on three different routes, around 3000 tourists visit the summit every day. A particularly beautiful view from the summit is when the sun rises over the Pacific . Many mountaineers take a break in one of the huts located between 3000 and 3400 m and set off again at around two o'clock at night. The highest station Gogōme ( 五 合 目 , "5th station") that can be reached by regular motorized traffic is at about 2300 m. The road there is only open to buses during Obon time . There are a total of four hiking routes to the top of Mount Fuji today. They differ from the starting altitude, the ascent, the length, the ascent and the duration. All routes start at the respective fifth station, which are at different heights. An overview of all routes:

- Yoshida Route ( 吉田 ル ー ト ), the most popular, starts at 2300 m

- Fujinomiya Route ( 富士 宮 ル ー ト ), the shortest but steepest, starts at 2400 m

- Subashiri Route ( 須 走 ル ー ト ), the sandiest, starts at 2000 m

- Gotemba Route ( 御 殿 場 ル ー ト ), the longest and the lowest starting at 1450 m

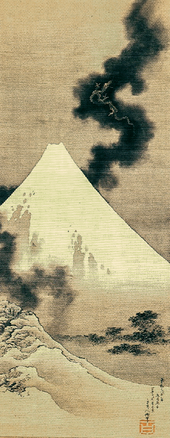

The Fuji in Japanese art

Because of its very symmetrical volcanic cone , Mount Fuji is considered to be one of the most beautiful mountains in the world and is a common theme in Japanese art . The mountain is also a common feature in Japanese literature and is a popular subject of many poems.

One of the earliest mentions of the mountain can be found in the anthology of poems Man'yōshū with the following long poem ( chōka ) by Yamabe no Akahito ( bl. 724-736):

| Japanese | transcription | translation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Old Japanese | Modern | ||

|

之天地 |

ame 2 tuti no 2 |

Ametsuchi no |

Heaven and earth, |

The oldest surviving artistic representation of Fuji comes from the Heian period and can be found on a paper-covered sliding wall from the 11th century. The most famous work is probably Katsushika Hokusai's picture cycle 36 Views of Mount Fuji , including above all the picture The Great Wave off Kanagawa from 1830 .

World heritage

On June 22, 2013, the mountain with a total of 25 locations was added to the UNESCO World Heritage List as a World Heritage Site because of its importance as a “holy place and source of artistic inspiration” . The locations cover 20,702 hectares and are specifically:

|

|

Web links

- Entry on the UNESCO World Heritage Center website ( English and French ).

- Rembert Biemond: The volcano as Mecca, article in the NZZ from 2001

- Suzuki Masataka: " Fuji shinkō " . In: Encyclopedia of Shinto. Kokugaku-in , November 11, 2006 (English) and Nogami Takahiro: "Fuji / Sengen Shinkō" . In: Encyclopedia of Shinto. Kokugaku-in , February 24, 2007 (English)

- Official Web Site of Mt.Fuji Climbing (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Pointdexter, Joseph: Between heaven and earth. The 50 highest peaks. Könemann, Cologne 1999, ISBN 3-8290-3561-6 , p. 80

- ↑ a b Term “Fuji (富士山 / ふ じ さ ん)”, English / Japanese: tangorin.com on tangorin.com; accessed on April 4, 2018

- ↑ Term “Fuji (富士山 / ふ じ さ ん)”, German / Japanese: wadoku.de on wadoku.de; accessed on April 4, 2018

- ↑ a b term " Fujiyama " on duden.de; accessed on April 4, 2018

- ↑ a b term " Fudschijama " on duden.de; accessed on April 4, 2018

- ↑ 富士山 情報 コ ー ナ ー . MLIT , accessed March 15, 2012 (Japanese).

- ↑ a b c Pointdexter, Joseph: Between heaven and earth. The 50 highest peaks. Könemann, Cologne 1999, ISBN 3-8290-3561-6 , p. 81

- ↑ a b c d e Tomasz Majtczak: Familiar and unfamiliar names of Mount Fuji . engl. Translation of Znane i nieznane określenia góry Fudzi . Ed .: Manggha and Jagiellonian University (= Fuji-san i Fuji-yama. Narracje o Japonii ). March 21, 2012.

- ↑ a b Hans Adalbert Dettmer: Ainu grammar . Part II: Explanations and registers . Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1997, ISBN 3-447-03761-X , p. 9–10 ( limited preview in Google Book Search).

- ^ Peter Kapitza: Japan in Europe. Texts and image documents on European knowledge of Japan from Marco Polo to Wilhelm von Humboldt. Backing band. Iudicium, Munich 1990, p. 9-10 .

- ^ Peter Kapitza: Japan in Europe. Texts and image documents on European knowledge of Japan from Marco Polo to Wilhelm von Humboldt . tape 1 . Iudicium, Munich 1990, p. 314, 355, 497, 517, 701 and 885 .

- ↑ Engelbert Kaempfer: Works. Today's Japan . Ed .: Wolfgang Michel, Barend J. Terwiel. tape 1 . Iudicium, Munich 2001, p. 391 and 407 .

- ↑ Engelbert Kaempfer: Today's Japan . Ed .: Wolfgang Michel, Barend J. Terwiel. tape 1 . Iudicium, Munich 2001, p. 86, 401 and 407-408 .

- ↑ Engelbert Kaempfer: Works. Today's Japan . Ed .: Wolfgang Michel, Barend J. Terwiel. tape 1 . Iudicium, Munich 2001, p. 407 .

- ↑ a b c Nogami Takahiro: " Fuji / Sengen Shinkō " . In: Encyclopedia of Shinto. Kokugaku-in , February 24, 2007 (English)

-

↑ a b 御 祭神 ・ 御 由 緒 . Fujisan Hongū Sengen Taisha, accessed June 23, 2013 (Japanese). Mount Fuji Hongu Sengentaisha. Fujisan Hongū Sengen Taisha, accessed June 23, 2013 .

- ^ A b Jean Herbert: Shintô: At the Fountainhead of Japan . Routledge, 2011, ISBN 978-0-203-84216-4 , pp. 420–421 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Suzuki Masataka: " Fuji shinkō " . In: Encyclopedia of Shinto. Kokugaku-in , November 11, 2006 (English)

- ↑ Ted Taylor: Mount Fuji has long been an icon. In: The Japan Times. June 23, 2013, accessed June 25, 2013 .

- ↑ 富士山 原始 林 及 び 青木 ヶ 原 樹 海 . Bunka-chō , accessed January 17, 2015 (Japanese).

- ↑ 登山 口 と 登山 ル ー ト . In: 富士 登山 オ フ ィ シ ャ ル サ イ ト ("Official Fuji Mountaineering Website"). Retrieved July 25, 2016 (Japanese).

-

↑ cf. Herbert E. Plutschow: Chaos and Cosmos: Ritual in Early and Medieval Japanese Literature . Brill, Leiden 1990, ISBN 90-04-08628-5 , pp. 115–116 ( limited preview in Google Book search). ,

Haruo Shirane (Ed.): Traditional Japanese Literature: An Anthology, Beginnings to 1600 . Columbia University Press, New York 2012, ISBN 978-0-231-15731-5 , pp. 60–61 ( limited preview in Google Book Search - Translator: Anne Commons). and

Bruno Lewin : Japanese Chrestomathy from the Nara Period to the Edo Period . I. Comment. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1965, p. 48–49 ( limited preview in Google Book search). - ↑ Fuji, Japan's highest mountain, becomes a World Heritage Site. In: Der Tagesspiegel. June 22, 2013. Retrieved June 23, 2013 .

- ↑ Qatar and Fiji get their first World Heritage sites as World Heritage Committee makes six additions to UNESCO List. In: World Heritage. UNESCO, June 22, 2013, accessed July 4, 2013 .

- ↑ Fujisan, sacred place and source of artistic inspiration: Maps. In: World Heritage. UNESCO, accessed July 4, 2013 .