Julius Pomponius Laetus

Julius Pomponius Laetus (* 1428 in Diano [today Teggiano ], Province of Salerno , † June 9, 1498 in Rome ; Italian Giulio Pomponio Leto ) was an influential Italian humanist . He founded a community of scholars who were a loose circle of his humanistic friends and students and who pursued studies in classical studies. Later, the term Accademia Romana was used for this community .

Pomponius' research on the topography of ancient Rome was groundbreaking. As editor and commentator, he was one of the most important scholars of his time in the field of classical philology . As a university lecturer, he showed an extraordinary ability to inspire his numerous students for classical studies.

The conflict between the community of Pomponius and Pope Paul II caused a sensation . The Pope suspected the humanists of heresy (heresy) and of a conspiracy against his rule. The suspects, including Pomponius, were temporarily incarcerated. After a year Pomponius was released because the suspicion was not confirmed.

Life

Origin and youth

Pomponius was an illegitimate son of the Count of Marsico Giovanni Sanseverino from an old, famous noble family of Norman origin. He spent his childhood and youth in his father's castle in Diano. The count died on December 19, 1444. He left a will in which he did not mention the illegitimate son. Pomponius was now in a precarious position because his stepmother was hostile to him. Around the middle of the century he left his home in the Kingdom of Naples and went to Rome, where he settled permanently. According to an anecdote, he abruptly distanced himself from his family. Out of enthusiasm for antiquity, instead of his Italian name, he used the Latin form Julius Pomponius with the addition Laetus ("the happy one").

Studies and first phase of teaching

In Rome Pomponius studied rhetoric with the famous humanist Lorenzo Valla and his successor Pietro Odi (Oddi) da Montopoli. After Odi's death (1462/63) he was given his professorship in rhetoric at the university, the studium urbis . In addition to his teaching activities there, he held private lectures, which apparently were better attended than the university. His concept was that of a comprehensive historical-philological study of antiquity, which combined the text-critical study of ancient sources with that of archaeological sites and finds. He was eager to compare the information given by the ancient authors with the archaeological findings and to identify the historical locations. He also encouraged his students to make such efforts. Later research, while discarding many of his identifications, has recognized his role as a pioneer. His morning lecture is said to have been so crowded that listeners turned up at midnight to secure their places. Many did not find admission. His salary rose from 150 Roman guilders in 1474 to 300 guilders (attested for 1496); it enabled him to own two houses on the Quirinal .

As a humanist, he did not see Roman antiquity as a mere object of aloof curiosity and erudition, but as a “classic” model for the present and specifically for one's own way of life. He was known for his simple, frugal way of life. He was busy collecting antiques . His house became the center of a circle of friends and students who shared his enthusiasm. They used Greek or Latin pseudonyms and formed a literary community (sodalitas litteratorum) . They met for discussions on philological and historical topics and to recite their own Latin poems and speeches and performed comedies by Plautus and Terence as well as humanistic plays. The group dealt not only with literature and architecture, religious and administrative history, but also with everyday life in ancient Rome (culinary arts, gardening).

This community of scholars only became known later under the name Academia Romana , the term academy was usually used in Pomponius' time for the university (the Studium Urbis ). The community of scholars was later named Academia Pomponiana after its founder to distinguish it from other Roman academies. Prominent academics were Bartolomeo Platina and Filippo Buonaccorsi (pseudonym: Callimachus Experiens). The academy was a loose circle; it did not have its own rooms or facilities.

Stay in Venice and imprisonment

In 1467 Pomponius left Rome with the intention of acquiring knowledge of Greek and Arabic in the Ottoman Empire and first went to Venice. There he gave private lessons to two sons of distinguished families. He made friends with his two students, who adored him profusely. One of them was the young brother of Cecilia Contarini, who was married to Giovanni Tron, a son of Doge Niccolò Tron . Pomponius glorified his young friend in poetry. According to his own statements, his close relationships with his students earned him a charge of “ sodomy ” (homosexuality). This was the death penalty in Venice, which was often carried out at the stake . Pomponius was arrested. This did not affect his friendly relationship with the Tron family.

However, there was no trial in Venice, but the defendant was extradited to Rome in March 1468, where another matter was investigated against him. In Rome, in his absence, a serious conflict had broken out between the Academy and Pope Paul II . Paul was not well disposed towards the Academy and had been sharply provoked by Platina. The conflict escalated when, in February 1468, the academics were accused of plotting to assassinate the Pope and establish a republican constitution. Such endeavors, whose representatives referred to the greatness and freedom of the ancient Roman republic, had supporters in Rome as early as the 12th century ( Arnold von Brescia ) and, from the perspective of the popes, were a direct threat to their secular power over the city. Such conspirators and rebels had also appeared under Paul's predecessors, Popes Nicholas V (1447–1455) and Pius II (1458–1464). Therefore Paul proceeded with severity. The academy was dissolved and a group of humanists, including Pomponius, were imprisoned in Castel Sant'Angelo . Pomponius was allowed to work scientifically while in prison. The main suspects - whom he was not one of - were tortured.

It is unclear whether it was just an investigation or a formal court case. The five charges against Pomponius were: involvement in the conspiracy, heresy, insulting majesty of the Pope, disrespectful remarks about the priests and sodomy. The main allegations were conspiracy and heresy. In the course of the investigation, the suspicion of conspiracy soon turned out to be unfounded, whereupon some prisoners were released. Most, however, had to stay in Castel Sant'Angelo, as the charge of heresy had yet to be clarified. But they found influential advocates (including Cardinal Bessarion ) and were treated mildly after it was found that they were politically harmless. Pomponius, for whom Giovanni Tron had also campaigned, was released in March or April 1469, and the Pope, like other accused, provided him with financial support for the release. He soon got his chair back.

The accusations against the academics followed a common pattern; In other charges of the period, too, a close connection was made between sodomy, social upheaval, and heresy. It is widely believed that there was an intrinsic connection between these three actions; they were considered unnatural and characteristic of people who had completely lost their moral standards. In the case of Pomponius, however, there are some indications - especially poetry - that he was actually homoerotic and that this tendency met with resonance in his environment. He apparently had a relationship of this kind at the time of his arrest with the almost twenty-year-old poet Antonius Septimuleius Campanus (Antonio Settimuleio Campano), a member of the academy who was among those imprisoned in Castel Sant'Angelo and soon after his release from the consequences of the rigors of imprisonment and torture died. Pomponius wrote an inscription for the grave, in which he wanted to be buried next to his "incomparable friend".

Rehabilitation and second phase of teaching

In the course of his rehabilitation, Pomponius was not only able to resume teaching, but also after the death of Paul II, under the humanist-friendly Pope Sixtus IV., He obtained permission to start the academy again. As a precaution, the “second academy” took the form of a religious community. In 1478 it was formally institutionalized with papal approval. The orientation of the circle hardly changed. In April, the group celebrated Parilia (Palilia), an ancient festival commemorating the founding of Rome, and superficially linked this celebration with the cult of three saints, whose feast day was Parilia Day. Members of the academy explored the catacombs (for the first time since ancient times) and immortalized their names there. They called Pomponius (probably jokingly) the Pontifex maximus .

Pomponius's teaching and research activities in Rome were interrupted by two trips. The first (iter Scythicum) was an extensive study trip that took him to Germany and Eastern Europe. The dating is controversial, the approaches vary between 1472 and 1480. From Rome he set out for Nuremberg , from there he turned east and finally reached the Black Sea . After visiting Northern Greece, he stayed in Regensburg on the return journey . The notes (commentariola) he made on this trip are lost. The destination of the second trip (iter Germanicum) , which probably took place in the winter of 1482/1483, was the court of Kaiser Friedrich III. Pomponius went to Germany to ask the emperor for the right to crown poets . This right was originally an imperial monopoly. Friedrich granted the Italian humanist's wish. In doing so, he aroused the displeasure of the German humanist Konrad Celtis , who deplored this step as an unfounded surrender of an imperial privilege. From then on, poets were coronated in the Roman scholarly community.

Pomponius disapproved of the luxury of the clergy. Unlike many other humanists, he never aspired to a spiritual career or an employment in the church service. He was married and had two daughters, Nigella and Fulvia. Nigella supported him in philological work.

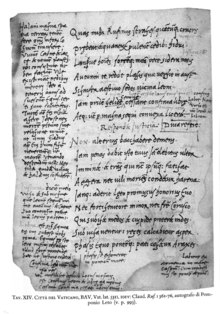

Pomponius played an important role in the spread of humanistic writing. He preferred the humanistic italics created by Niccolò Niccoli in the 20s of the 15th century , which he modified slightly. The script, which he used from 1470 onwards, is known from a number of autographs and marginalia . She was imitated by his students and also influenced correspondence partners such as Angelo Poliziano .

The pupils of Pomponius included Alessandro Farnese (the future Pope Paul III ), Ermolao Barbaro the Younger , the eminent archaeologist Andrea Fulvio, Pietro Marso and Marcantonio Sabellico . Johannes Reuchlin , Konrad Peutinger , Jacopo Sannazaro , Giovanni Pontano and Girolamo Balbi (Hieronymus Balbus, later Bishop of Gurk ) also attended his classes . After all, his reputation was so great that forty bishops attended his funeral, although he had never been noticed by Christian zeal throughout his life. He was buried in the Church of San Salvatore in Lauro .

Works

- A Latin grammar that has been handed down in several versions, including a version (printed in Venice in 1484). It was intended for school children. Two other grammatical writings, which have come down anonymously, also seem to come from Pomponius.

- A work on the offices and the judiciary of the Romans (De Romanorum magistratibus, sacerdotiis, iurisperitis et legibus libellus) , which gained wide circulation.

- Caesares , also titled Romanae historiae compendium ab interitu Gordiani Iunioris usque ad Iustinum tertium ("Outline of Roman history from the death of Gordian the Younger to Justin III"), a late work that Pomponius wrote shortly before his death and the later Cardinal Francisco de Borja (first printed in Venice in 1499). It deals with the Roman and Byzantine emperors from 244 to the end of the 7th century (from Philip Arabs to Justinian II , whom Pomponius erroneously calls Justin III). Pomponius mainly used material from the Historia Augusta , the historical work of Johannes Zonaras and the Historia Romana of Paulus Diaconus ; he also consulted the breviary of Eutropius . The work received a lot of attention in the 16th and 17th centuries; it has been printed several times and is often quoted. In 1549 an Italian translation by Francesco Baldelli appeared.

- Defensio in carceribus (“Defense in the Dungeon”) , written in custody in Castel Sant'Angelo .

- A guided tour through the ancient sites of Rome recorded by a pupil of Pomponius ( Excerpta a Pomponio dum inter ambulandum cuidam domino ultramontano reliquias ac ruinas Urbis ostenderet; a corrupted version is entitled De antiquitatibus urbis Romae libellus or De Romanae urbis vetustate ) in early prints . This font was not printed until 1510; an Italian translation appeared in Venice in 1550.

- A revision of a list of Roman sights (De regionibus et Urbis vetustatibus descriptio) .

- Biographies of some ancient authors: Virgil (De vita P. Virgilii Maronis succincta collectio) , Lukan (prefixed the first edition of Lukan's works published in 1469), Lucretius , Sallust (printed in 1490), Statius and Varro .

- Poems, including Stationes Romanae quadragesimali ieiunio ( distiches about the Roman churches visited by pilgrims during Lent ; two versions have been preserved).

Comments

- A commentary on the Punica of Silius Italicus , which has also come down to us as a transcript of a student from Pomponius' classes.

- A commentary on Sallust's Bellum Iugurthinum , received as a transcript of a student from Pomponius' class.

- A commentary on the Germania of Tacitus , as a transcript of a student from Pomponius' narrated lessons.

- A commentary on Varros De lingua Latina ; Dictata (notes from students from Pomponius' class) are also preserved .

- A commentary on Virgil's poems in the form of scholia and glosses, which has been handed down in various versions .

- Other ancient authors whose works Pomponius commented on are Cicero , Claudian , Columella , Horace , Lukan, Martial , Ovid , Quintilian , Statius and Valerius Flaccus .

Editions of ancient works

- Many editions of works by ancient authors, including Donat (Ars minor) , Festus (De verborum significatione) , Pliny ( letters , books 1-9), Sallust , Silius Italicus, Terenz and Varro ( De lingua Latina , the first edition from 1471).

reception

In the early modern period, ecclesiastical authors objected to Pomponius' religious attitude, but the judgments of posterity were mainly shaped by enthusiastic descriptions from his group of students. Marcantonio Sabellico wrote a biography of the scholar (Vita Pomponii) , which is the main source of his life; it was published in 1499. Further biographical sources from the group of students that convey a very positive image are a letter from Michele Ferno ( Iulii Pomponii Laeti elogium historicum , 1498) and the funeral oration given by Pietro Marso. Paolo Cortesi, a contemporary of Pomponius, praised his elegant style, Giovanni Pontano emphasized his care. In the early 16th century, Pomponius was considered an authority on urban Roman archeology; Pietro Bembo valued him as a philologist.

Pomponius' handwriting influenced the Paduan Bartolomeo Sanvito, who belonged to his circle. Sanvito dissolved the italics into a sequence of individual letters and thus gave it a form in which it was suitable for letterpress printing. The cursive, which the Venetian printer and publisher Aldo Manuzio introduced to letterpress printing in 1501, is very similar to Sanvito's script. A number of Pomponius manuscripts, including autographs, came into the possession of the humanist Fulvio Orsini , who bequeathed them to the Vatican Library .

In modern research, the philological achievements of Pomponius have been assessed differently. The Latinist Remigio Sabbadini was very critical . He emphasized the humanist's poor knowledge of Greek. Pomponius had no text-critical method, his emendations were bold and flawed in prosody . In dealing with his sources, he was guilty of numerous negligence. He also plagiarized, and some of his statements about ancient authors and their works were fabricated. Although he was an important humanist and promoter of classical studies, he was not a good philologist. In more recent research, Sabbadini's criticism is relativized, since it is based on modern standards; it should be noted that numerous scholars of the 15th and 16th centuries considered Pomponius an excellent Latinist.

swell

- Michaelis Ferni Mediolanensis Julii Pomponii Laeti elogium historicum . In: Johann Albert Fabricius (ed.): Bibliotheca Latina mediae et infimae aetatis , volumes 5/6, Akademische Druck- und Verlagsanstalt, Graz 1962 (reprint of the Florence edition 1858), pp. 629–632

- Marcantonio Sabellico: Pomponii vita , ed. Emy Dell'Oro. In: Maria Accame: Pomponio Leto. Vita e insegnamento . Edizioni Tored, Tivoli 2008, ISBN 978-88-88617-16-9 , pp. 201-219 (critical edition with Italian translation)

- Petri Marsi funebris oratio habita Romae in obitu Pomponii Laeti . In: Marc Dykmans: L'humanisme de Pierre Marso . Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Città del Vaticano 1988, ISBN 88-210-0549-6 , pp. 78–85 (with a French summary; Latin text in the footnotes)

Editions and translations

- Maria Accame (Ed.): Vita di Marco Terenzio Varrone . In: Maria Accame: Pomponio Leto. Vita e insegnamento . Edizioni Tored, Tivoli 2008, ISBN 978-88-88617-16-9 , pp. 193-200 (critical edition of Pomponius' biography of Varros with Italian translation)

- Shane Butler (Ed.): Angelo Poliziano: Letters , Volume 1: Books I – IV . Harvard University Press, Cambridge (Massachusetts) 2006, ISBN 0-674-02196-7 (contains Pomponius' correspondence with Poliziano; Latin texts with English translation)

- Isidoro Carini (ed.): La "Difesa" di Pomponio Leto . In: Nozze Cian - Sappa-Flandinet. 23 ottobre 1893 . Istituto italiano d'arti grafiche, Bergamo 1894, pp. 151-193

- Cesare D'Onofrio: Visitiamo Roma nel Quattrocento. La città degli Umanisti . Romana Società Editrice, Rome 1989 (contains pp. 269–291 the Latin text of the Excerpta a Pomponio dum inter ambulandum cuidam domino ultramontano reliquias ac ruinas Urbis ostenderet with Italian translation)

- Marc Dykmans (Ed.): La "Vita Pomponiana" de Virgile . In: Humanistica Lovaniensia 36, 1987, pp. 85–111 (critical edition of Pomponius' biography of Virgil)

- Nicola Lanzarone (ed.): Il commento di Pomponio Leto all'Appendix Vergiliana. Edizioni ETS, Pisa 2018, ISBN 978-88-46752-36-9 (critical edition)

- Germain Morin (ed.): Les distiques de Pomponio Leto sur les stations liturgiques du carême . In: Revue bénédictine 35, 1923, pp. 20-23 ( Stationes Romanae quadragesimali ieiunio , first version)

- Frans Schott (Franciscus Schottus) (Ed.): Itinerarii Italiae rerumque Romanarum libri tres , 4th edition, Antwerp 1625, pp. 505–508 ( Stationes Romanae quadragesimali ieiunio , second version)

- Giuseppe Solaro (ed.): Pomponio Leto: Lucrezio . Sellerio, Palermo 1993 (critical edition of Pomponius' biography of Lucretius with Italian translation and commentary)

- Giuseppe Solaro (ed.): Lucrezio. Biography umanistiche . Edizioni Dedalo, Bari 2000, ISBN 88-220-5803-8 , pp. 10f., 25-30 (critical edition of Pomponius' biography of Lucretius)

- Roberto Valentini, Giuseppe Zucchetti (eds.): Codice Topografico della Città di Roma . Volume 1, Istituto Storico Italiano per il Medio Evo, Rome 1940, pp. 193-258 (critical edition of De regionibus et Urbis vetustatibus descriptio )

- Roberto Valentini, Giuseppe Zucchetti (eds.): Codice Topografico della Città di Roma . Volume 4, Istituto Storico Italiano per il Medio Evo, Rome 1953, p. 421–436 (critical edition of the Excerpta a Pomponio dum inter ambulandum cuidam domino ultramontano reliquias ac ruinas Urbis ostenderet )

literature

- Maria Accame: Pomponio Leto. Vita e insegnamento. Edizioni Tored, Tivoli 2008, ISBN 978-88-88617-16-9 .

- Phyllis Pray Bober: The Legacy of Pomponius Laetus. In: Stefano Colonna (ed.): Roma nella svolta tra Quattro e Cinquecento. Atti del Convegno Internazionale di Studi . De Luca, Roma 2004, ISBN 88-8016-610-7 , pp. 455-464.

- Chiara Cassiani, Myriam Chiabò (ed.): Pomponio Leto e la prima Accademia Romana. Giornata di studi (Roma, December 2, 2005). Roma nel Rinascimento, Rome 2007, ISBN 88-85913-48-2 .

- Max Herrmann : The emergence of professional acting in ancient and modern times. Edited and with an obituary by Ruth Mövius. Henschel, Berlin 1962, pp. 195-260 ( digitized version ).

- Giovanni Lovito: Pomponio Leto politico e civile. L'Umanesimo italiano tra storia e diritto (= Quaderni Salernitani. Volume 18). Laveglia, Salerno 2005, ISBN 88-88773-38-X .

- Giovanni Lovito: L'opera ei tempi di Pomponio Leto (= Quaderni Salernitani. Volume 14). Laveglia, Salerno 2002.

- Anna Modigliani et al. (Ed.): Pomponio Leto tra identità locale e cultura internazionale. Atti del convegno internazionale (Teggiano, 3–5 October 2008). Roma nel Rinascimento, Rome 2011, ISBN 88-85913-52-0 .

- Richard J. Palermino: The Roman Academy, the Catacombs and the Conspiracy of 1468. In: Archivum Historiae Pontificiae. Volume 18, 1980, pp. 117-155.

Web links

- Leto, Pomponio. In: Enciclopedie on line. Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, Rome.

- Repertory Pomponianum

- Works by Julius Pomponius Laetus in the complete catalog of incunabula

- Literature database of the Regesta Imperii

Remarks

- ^ Italo Gallo: Piceni e Picentini: Paolo Giovio e la patria di Pomponio Leto . In: Rassegna Storica Salernitana , Nuova serie, fascicolo 5 (= annata III / 1), 1986, pp. 43-50, here: 45; on Diano's place of birth see Giovanni Lovito: L'opera ei tempi di Pomponio Leto , Salerno 2002, pp. 11–13.

- ^ Richard J. Palermino: The Roman Academy, the Catacombs and the Conspiracy of 1468 . In: Archivum Historiae Pontificiae 18, 1980, pp. 117–155, here: 121.

- ^ Paolo Cherubini: Studenti universitari romani del secondo Quattrocento a Roma e altrove . In: Roma e lo Studium Urbis , Rom 1992, pp. 101–132, here: 129.

- ↑ For the breadth of his range of interests see Maria Accame Lanzillotta: L'insegnamento di Pomponio Leto nello Studium Urbis . In: Lidia Capo, Maria Rosa Di Simone (ed.): Storia della Facoltà di Lettere e Filosofia de “La Sapienza” , Rome 2000, pp. 71–91.

- ↑ Giovanni Lovito: L'opera ei tempi di Pomponio Leto , Salerno 2002, p. 24. For the lectures, see Maurizio Campanelli, Maria Agata Pincelli: La lettura dei classici nello Studium Urbis tra Umanesimo e Rinascimento . In: Lidia Capo, Maria Rosa Di Simone (eds.): Storia della Facoltà di Lettere e Filosofia de “La Sapienza” , Rome 2000, pp. 93-195, here: 103, 125, 128, 139, 143f.

- ^ Egmont Lee: Sixtus IV and Men of Letters , Rom 1978, p. 178.

- ^ Sara Magister: Pomponio Leto collezionista di antichità. Note sulla tradizione manoscritta di una raccolta epigrafica nella Roma del tardo Quattrocento . In: Xenia Antiqua 7, 1998, pp. 167-196; Sara Magister: Pomponio Leto collezionista di antichità: addenda . In: Massimo Miglio (ed.): Antiquaria a Roma. Intorno a Pomponio Leto e Paolo II , Rome 2003, pp. 51-124.

- ↑ On the performances and Pomponius' relationship to the ancient theater, see Antonio Stäuble: La commedia umanistica del Quattrocento , Firenze 1968, pp. 212–214; Phyllis Pray Bober: The Legacy of Pomponius Laetus . In: Stefano Colonna (ed.): Roma nella svolta tra Quattro e Cinquecento , Rome 2004, pp. 455–464, here: 460; Maria Accame: Pomponio Leto. Vita e insegnamento , Tivoli 2008, pp. 60f.

- ^ For the name of the community, see Concetta Bianca: Pomponio Leto e l'invenzione dell'Accademia romana . In: Marc Deramaix et al. (Ed.): Les académies dans l'Europe humaniste. Idéaux et pratiques , Genève 2008, pp. 25-56.

- ^ Susanna de Beer: The Roman 'Academy' of Pomponio Leto: From an Informal Humanist Network to the Institution of a Literary Society . In: Arjan van Dixhoorn, Susie Speakman Sutch (ed.): The Reach of the Republic of Letters , Vol. 1, Leiden 2008, pp. 181-218, here: 185f., 189-193.

- ↑ See also Josef Delz : An unknown letter from Pomponius Laetus . In: Italia medioevale e umanistica 9, 1966, pp. 417-440, here: 420-424.

- ↑ On these events see Josef Delz: An unknown letter from Pomponius Laetus . In: Italia medioevale e umanistica 9, 1966, pp. 417-440, here: 422-425.

- ↑ Ulrich Pfisterer : Lysippus und seine Freunde , Berlin 2008, pp. 44–46, 281–285.

- ↑ On this ancient festivity renewed by Pomponius see Paola Farenga: Considerazioni sull'Accademia romana nel primo Cinquecento . In: Marc Deramaix et al. (Ed.): Les académies dans l'Europe humaniste. Idéaux et pratiques , Genève 2008, pp. 57–74, here: 62–65; Phyllis Pray Bober: The Legacy of Pomponius Laetus . In: Stefano Colonna (ed.): Roma nella svolta tra Quattro e Cinquecento , Rome 2004, pp. 455–464, here: 459f.

- ^ Richard J. Palermino: The Roman Academy, the Catacombs and the Conspiracy of 1468 . In: Archivum Historiae Pontificiae 18, 1980, pp. 117–155, here: 140–142.

- ↑ Maria Accame: Note scite nei commenti di Pomponio Leto . In: Anna Modigliani u. a. (Ed.): Pomponio Leto tra identità locale e cultura internazionale , Rome 2011, pp. 39–55; Massimo Miglio: Homo totus simplex: Mitografie di un personaggio . In: Anna Modigliani u. a. (Ed.): Pomponio Leto tra identità locale e cultura internazionale , Rome 2011, pp. 1–15, here: 9.

- ↑ John L. Flood: Viridibus lauric ramis et foliis decoratus. On the history of the imperial coronation of poets . In: Anette Baumann et al. (Ed.): Reichspersonal. Officials for Kaiser and Reich , Cologne 2003, pp. 353–377, here: 358.

- ^ Susanna de Beer: The Roman 'Academy' of Pomponio Leto: From an Informal Humanist Network to the Institution of a Literary Society . In: Arjan van Dixhoorn, Susie Speakman Sutch (ed.): The Reach of the Republic of Letters , Vol. 1, Leiden 2008, pp. 181-218, here: 181-184.

- ↑ James Wardrop: The Scipt of Humanism , Oxford 1963, pp. 22f .; Paolo Cherubini, Alessandro Pratesi: Paleografia latina , Città del Vaticano 2010, pp. 604f.

- ↑ See also José Ruysschaert: Les manuels de grammaire latine composés par Pomponio Leto . In: Scriptorium 8, 1954, pp. 98-107 (with a critical edition of the dedication letter); José Ruysschaert: A propos des trois premières grammaires latines de Pomponio Leto . In: Scriptorium 15, 1961, pp. 68-75; Robert Black: Humanism and Education in Medieval and Renaissance Italy , Cambridge 2001, pp. 137-142.

- ↑ Rossella Bianchi, Silvia Rizzo: Manoscritti e grammaticali opere nella Roma di Niccolò V . In: Mario De Nonno et al. (Ed.): Manuscripts and Tradition of Grammatical Texts from Antiquity to the Renaissance , Vol. 2, Cassino 2000, pp. 587-653, here: 638-650.

- ^ Maria Accame: Pomponio Leto. Vita e insegnamento , Tivoli 2008, pp. 167-174.

- ↑ Francesca Niutta: Il Romanae historiae compendium di Pomponio Leto dedicato a Francesco Borgia . In: Davide Canfora et al. (Ed.): Principato ecclesiastico e riuso dei classici. Gli umanisti e Alessandro VI , Rome 2002, pp. 321-354; Daniela Gionta: Ritrovamenti pomponiani . In: Studi medievali e umanistici 4, 2006, pp. 386-399; Francesca Niutta: Fortune e sfortune del Romanae historiae compendium di Pomponio Leto . In: Anna Modigliani u. a. (Ed.): Pomponio Leto tra identità locale e cultura internazionale , Rome 2011, pp. 137–163; Johann Ramminger: Pomponio Leto's Nachleben: A phantom in need of research? In: Anna Modigliani u. a. (Ed.): Pomponio Leto tra identità locale e cultura internazionale , Rome 2011, pp. 237–250, here: 239–241.

- ↑ See Giovanni Lovito: L'opera ei tempi di Pomponio Leto , Salerno 2002, pp. 34–41.

- ↑ See Berthold Louis Ullman: Studies in the Italian Renaissance , 2nd edition, Rome 1973, pp. 365–372.

- ^ Edward L. Bassett and others: Silius Italicus, Tiberius Catius Asconius . In: Ferdinand Edward Cranz, Paul Oskar Kristeller (eds.): Catalogus translationum et commentariorum , Vol. 3, Washington (DC) 1976, pp. 341-398, here: 373-383; Arthur John Dunston: A Student's Notes of Lectures by Giulio Pomponio Leto . In: Antichthon 1, 1967, pp. 86-94.

- ↑ Patricia J. Osmond, Robert W. Ulery: Sallustius Crispus, Gaius . In: Virginia Brown (ed.): Catalogus translationum et commentariorum , Vol. 8, Washington (DC) 2003, pp. 183-326, here: 291f.

- ^ Robert W. Ulery: Cornelius Tacitus. Addenda et corrigenda . In: Virginia Brown (ed.): Catalogus translationum et commentariorum , Vol. 8, Washington (DC) 2003, p. 335.

- ^ Virginia Brown: Varro, Marcus Terentius . In: Ferdinand Edward Cranz, Paul Oskar Kristeller (eds.): Catalogus translationum et commentariorum , Vol. 4, Washington (DC) 1980, pp. 451-500, here: 467-474; Maria Accame Lanzillotta: "Dictata" nella scuola di Pomponio Leto . In: Studi medievali 34/1, 1993, pp. 315-324; Maria Accame Lanzillotta: Le annotazioni di Pomponio Leto ai libri VIII – X del De lingua Latina di Varrone . In: Giornale italiano di filologia 50, 1998, pp. 41-57; Maria Accame: I corsi di Pomponio Leto sul De lingua Latina di Varrone . In: Chiara Cassiani, Myriam Chiabò (ed.): Pomponio Leto e la prima Accademia Romana. Giornata di studi (Roma, December 2, 2005) , Rome 2007, pp. 1-24.

- ^ Fabio Stok: Il commento di Pomponio Leto all'Eneide di Virgilio . In: Studi Umanistici Piceni 29, 2009, pp. 251-273; Aldo Lunelli: Il commento virgiliano di Pomponio Leto . In: Atti del Convegno virgiliano di Brindisi nel bimillenario della morte , Perugia 1983, pp. 309-322; Giancarlo Abbamonte: Il commento di Pomponio Leto alle opere di Virgilio: problemi ecdotici . In: Anna Modigliani u. a. (Ed.): Pomponio Leto tra identità locale e cultura internazionale , Rome 2011, pp. 115–135.

- ^ Daniela Gionta: Il Claudiano di Pomponio Leto . In: Vincenzo Fera, Giacomo Ferraú (ed.): Filologia umanistica. Per Gianvito Resta , Vol. 2, Padova 1997, pp. 987-1032.

- ↑ Alessandro Perosa: L'edizione veneta di Quintiliano coi commenti del Valla, di Pomponio Leto e di Sulpizio da Veroli . In: Miscellanea Augusto Campana , Volume 2, Padova 1981, pp. 575-610, here: 576, 592-602.

- ↑ On the editions of Pomponius see Piero Scapecchi: Pomponio Leto e la tipografia fra Roma e Venezia . In: Paola Farenga (ed.): Editori ed edizioni a Roma nel rinascimento , Rome 2005, pp. 119–126, here: 119–122; Edward L. Bassett among others: Silius Italicus, Tiberius Catius Asconius . In: Ferdinand Edward Cranz, Paul Oskar Kristeller (ed.): Catalogus translationum et commentariorum , Vol. 3, Washington (DC) 1976, pp. 341-398, here: 381.

- ^ Johann Ramminger: Pomponio Leto's Nachleben: A phantom in need of research? In: Anna Modigliani u. a. (Ed.): Pomponio Leto tra identità locale e cultura internazionale , Rome 2011, pp. 237–250, here: 248f.

- ^ Massimo Miglio: Homo totus simplex: Mitografie di un personaggio . In: Anna Modigliani u. a. (Ed.): Pomponio Leto tra identità locale e cultura internazionale , Rome 2011, pp. 1–15, here: 5, 7.

- ↑ James Wardrop: The Scipt of Humanism , Oxford 1963, pp. 23-35; Paolo Cherubini, Alessandro Pratesi: Paleografia latina , Città del Vaticano 2010, pp. 606f .; Bernhard Bischoff : Palaeography of Roman Antiquity and the Occidental Middle Ages , 4th edition, Berlin 2009, p. 199.

- ↑ Compilation by Pierre de Nolhac: La bibliothèque de Fulvio Orsini , Paris 1887, pp. 198–208.

- ^ Remigio Sabbadini: Review by Vladimiro Zabughin: Giulio Pomponio Leto , vol. 2. In: Giornale storico della letteratura italiana 60, 1912, pp. 182-186, here: 184-186. Sabbadini's criticism is briefly summarized in his article Leto, Pomponio . In: Enciclopedia Italiana , Volume 20, Rome 1950, pp. 976f. ( online ).

- ^ Massimo Miglio: Homo totus simplex: Mitografie di un personaggio . In: Anna Modigliani u. a. (Ed.): Pomponio Leto tra identità locale e cultura internazionale , Rome 2011, pp. 1–15, here: 7; Rossella Bianchi: Gli studi su Pomponio Leto dopo Vladimiro Zabughin . In: Anna Modigliani u. a. (Ed.): Pomponio Leto tra identità locale e cultura internazionale , Rome 2011, pp. 17–25, here: 18.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Pomponius Laetus, Julius |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Pomponio Leto, Giulio |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Italian humanist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 1428 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Teggiano |

| DATE OF DEATH | June 9, 1498 |

| Place of death | Rome |