Ida Tarbell

Ida Minerva Tarbell (born November 5, 1857 in Hatch Hollow in Erie County , Pennsylvania , † January 6, 1944 in Bridgeport , Connecticut ) was an American writer and a pioneer of investigative journalism ( Muckraker ) as a journalist .

Life and journalistic stations

Youth and education

Ida Minerva Tarbell, the first child of Franklin Sumner and Elizabeth McCullough Tarbell, was born in her grandfather, Walter Raleigh McCullough's log cabin, on a farm in Hatch Hollow, near Wattsburg, northwest Pennsylvania. Her mother was a teacher before marriage. Her father wanted to buy farmland in Iowa for his family, but had to abandon his plans because of the panic of 1857 in New York and the subsequent economic crisis .

On August 27, 1859, Edwin Drake discovered an oil well in nearby Oil Creek, Titusville . Soon there was a run on the oil fields. Her father also saw his chance as a carpenter and joiner in this new industry and so they moved to Rouseville in 1860, where he manufactured wooden tanks for the storage of the extracted oil. The mother made Ida Tarbell attend Mrs. Rice's school and helped with homework. She described her childhood there between the oil rigs in her 1934 book Pioneer Women of the Oil Industry . In 1865, Ida Tarbell's father moved his business to Pithole City and she had three younger siblings. In 1870 the family moved into a new house in Titusville .

Most of the people at the time believed that it was enough for women to be able to read and write. A secondary school seemed like a waste of money. Ida Tarbell's parents didn't see it that way and even subscribed to Harper's Monthly , a literary magazine that published writers. So she learned the works z. From Dickens, Thackeray, Marian Evans and George Elliot. She was interested in nature and wanted to become a biologist. In 1872 she read the popular science magazine Popular Science Monthly .

1876 Ida Tarbell graduated from Titusville High School, top of the class, and began her studies - the only female student - that fall at Allegheny College in Meadville, PA, about 30 miles from Titusville, and graduated in biology in 1880. For the next two years she taught at the Poland Union Seminary in Mahoning County, Ohio, for an annual salary of $ 500. She found that teaching was not her goal in life. In June 1882 she returned to her tower room in Titusville.

The Chautauquan 1882-1891

In the fall, Ida Tarbell met Theodore L. Flood at her parents' home, a retired pastor who edited the monthly magazine The Chautauquan and offered her a job in Meadville, where she was in college . Ida Tarbell was supposed to provide background information on people and places as well as pronunciation tips. The printer, Adrian Coy, drew her attention to the need for neat documents and the importance of advertisements for the sheet. Dr. Herbert B. Adams and Dr. She met Richard T. Ely of Johns Hopkins University during summer camp when she was responsible for editing the Daily Herald . After growing up in the Chautauqua adult education movement, she initially worked enthusiastically for the newspaper, but soon the work became unbearable and she left the newspaper with the plan to go to Paris to learn more about the life of Madame Roland to find out from a person who had piqued their interest. During the seven years at The Chautauquan , she had learned three essential journalistic qualities:

- Balanced reporting requires presenting all sides of a problem.

- The information must be explained clearly and completely.

- Only exact reports give the reader confidence in a publication.

In Paris 1891-1894

Ida Tarbell longed for a new challenge. She wanted to know more about the women who lived during the French Revolution. Josephine Henderson, a college friend from Alleghy College, and Mary Handerson from the neighborhood wanted to accompany them to Paris - their friend joined them on the ship, so that there were four of them when they left in 1891. In preparation for her trip, she took lessons in conversation from the only French man in Titusville, Monsieur Claude, a dyer, and read with him France Adorée by Pierre-Jean de Béranger . They found rooms in a guesthouse near the Cluny Museum . The winters of 1891 and 1892 were particularly cold, and Ida Tarbell was glad the museums, libraries, and classrooms were heated. She earned her living from articles that she was able to offer to a network of six newspapers until her contributions had to give way to politics in 1892. In memory of Monsieur Claude, she wrote an article about Béranger and sent it to Scribner's Magazine as a “trial balloon” . The joy was huge when a check for $ 100 arrived. When Mr. Burlingame of Scribner's met Ida Tarbell that spring, she presented him with her ideas about Madame Roland. He was not averse, but said that this should be discussed in New York. Her article was printed in November 1893. She was particularly pleased that Harper's Bazaar also bought her items. A colleague of the Revue des Deux Mondes introduced Ida Tarbell to the writers in Paris. She was shocked by Madame Dieulafoy , who was wearing trousers, and made friends with Judith Gautier. Americans were also in Paris during the summer months, according to Dr. John Vincent and Charles D. Hazen from Johns Hopkins University and Fred Parker Emery from MIT in Boston. On the weekends, they invited the young women to go on excursions to the castles of Versailles and Fontainebleau , as well as the Cathedral of Chartres and Reims . In June 1892 Ida Tarbell learned of floods and fires in Titusville through acquaintances, but a telegram from her brother with the only word "Safe" reassured her.

In her senior year she attended a few lectures at the Sorbonne and the Collège de France . Samuel McClure , who founded McClure's Magazine in 1884, was impressed with her contributions from Paris and, at a personal meeting in Paris, offered Ida Tarbell a position on her return. He made it clear that his magazine was interested in articles about science, invention and adventure. She knew that Pierre Janssen was building an observatory on Mont Blanc and that Alphonse Bertillon was working on a new system for identifying criminals, but she admitted that she was having trouble understanding the technical terms. After all, she wrote about his laboratory. She particularly enjoyed an interview with Louis Pasteur, and she later brought him the publication in McClure's Magazine in September 1893.

In the footsteps of Madame Roland

The friends had left and now Ida Tarbell was walking in the footsteps of Madame Roland . Madame Marillier, a great-granddaughter of Mme. Roland, received Ida Tarbell warmly and invited her to her soirée on Wednesday evening. Here she met writers and politicians, and she enjoyed the evenings very much. In the Bibliothèque nationale de France she obtained access to Mme. Roland's papers, which had just been cataloged, and studied them diligently. In the spring of 1893 Madame Marillier invited Ida Tarbell to accompany her on a 14-day trip to her “Le Clos” winery near Theize, where her heroine had lived. They took the train to Villefranche-sur-Saône and continued to Le Clos by horse-drawn carriage. While Madame went about her business and visited friends, Ida Tarbell rummaged through the library.

Back in Paris, Ida Tarbell also experienced the economic crisis. Checks stopped coming from America and their money was running low. She did not want to ask anyone for help - especially not Mme. Marillier - so that in the summer of 1893 she was forced to take her fur coat to the pawn shop. Mme Marillier went to England and asked her to come with me. However, Ida Tarbell stayed in Paris and worked steadfastly on her book.

In 1894 she returned to her family in Pennsylvania. She wrote an article for Chatauquan Magazine on The Principles and Pastimes of the French Salon , which appeared in February 1894. She finished her book on Madame Roland, which Scribner published in 1896.

McClure's Magazine in New York 1894-1906

When Ida Tarbell went to New York to work for McClure's Magazine at the end of the year, with a salary of $ 40 a week, there was a lot of interest in Napoleon there . Gardiner Greene Hubbard , the father-in-law of Alexander Graham Bell , was an ardent admirer of Napoleon and had assembled a considerable collection of pictures and offered them to McClure for publication. Sam McClure had brought an article from England by Robert Sherard, a great-grandson of William Wordsworth , but Hubbard dismissed it as "too disparaging". Now he entrusted Ida Tarbell with this task, who happily accepted Samuel McClure's offer and hoped to return to Paris. But first she had to sift through Hubbard's collection at Hubbard's "Twin Oaks" summer residence in Chevy Chasesie, and found that Hubbard had the latest books and that Washington had both State Department correspondence with the government and all newspaper issues. So she had to give up her secret wish to travel to Paris and instead settle in the Congressional Library . After six weeks of work, she had finished her design, which also pleased Hubbard and Charles Joseph Bonaparte , the grandson of Jérôme Bonaparte. Ida Tarbell said modestly that she only provided the text that frames the pictures. McClure's Magazine ran to 80,000 copies after publication, and McClure urged Ida Tarbell to stay. Ida Tarbell liked the atmosphere there and John S. Philips, editor of the magazine, soon became a good friend and helper.

Your next assignment would be a popular series about Abraham Lincoln . Although John G. Nicolay and John M. Hay had just published Abraham Lincoln: A History in 1890 and Complete Works in 1894 , Sam McClure felt that there was still enough to write about Lincoln. So Ida Tarbell traveled to Washington to speak to John G. Nicolay , Lincoln's secretary from 1861 to 1865 and consul in France from 1865 to 1868, about her plan. John Nicolay said that he had nothing for her and advised her against such a hopeless assignment. After her article was published, he even announced that she was breaking into his property. She wrote popularly about Lincoln's life and thereby substantially reduced the value of Nicolay's property. In Chicago Ida Tarbell drank tea with Robert Lincoln, the former president's only living son, and received from him a daguerreotype of his father, which had not been published before. In the further course she found some of Lincoln's companions and met Carl Schurz . She was able to persuade him to publish his "reminiscences" (memories) in McClure's Magazine, which she was also allowed to edit and which appeared in several episodes from March 1906. Your total of nine (popular) articles about Lincoln appeared from December 1895 to October 1896 and immediately attracted public interest. In total, Ida Tarbell wrote eight books about Lincoln in her life.

In 1901 she wrote the story of the Declaration of Independence and in 1902 she dealt with Aaron Burr , who had been charged with high treason in Richmond, Virginia in 1807.

The History of the Standard Oil Company

After Ida Tarbell received Sam McClure's approval of a series on John Davison Rockefeller's Standard Oil Company , she wrote and researched the subject tirelessly for the next two years. Her old notes and letters from her brother from the time of the first oil boom were also helpful. John M. Siddal, now editor of The Chatauquean , who had since moved from Meadville to Cleveland, heard of her work and became Ida Tarbell's busiest collaborator. In his letters from Cleveland, for example, he described B. the daily life of John D. Rockefeller or sent statistics. She had the greatest difficulty finding and reading documents about the various hearings or committees of inquiry that had existed about Standard Oil and its subsidiaries. The report of the investigation ordered by President McKinley alone comprised 19 volumes of all the testimony.

One day in Sam McClure's office, when Mark Twain heard of Ida Tarbell's plans for Standard Oil, he put Ida Tarbell in touch with his friend Henry H. Rogers , who was still working for Standard Oil, in January 1902 . They exchanged memories of Rouseville, where Rogers lived and owned his first refinery. When asked what her story wanted to build on, Ida Tarbell replied "on documents beginning with the South Improvement Company ". Rogers wondered why she didn't come to Standard Oil immediately because they had changed their policy and were giving information. When he asked whether Ida Tarbell was ready to have the conversation in his office and whether she would also like to speak to Rockefeller, she replied “yes”. He promised her to talk to her. Their agreement worked for two years and Ida Tarbell visited Rogers at his 26 Broadway office. The only person she met there besides Rogers was his secretary, Miss Harrison. In addition to their conversations, Rogers also provided them with documents. Ida Tarbell soon realized that he also had a personal interest: the takeover of his then refinery in Buffalo, NY by the Vacuum Oil Company of Rochester, which belongs to Standard Oil. He said this case was a sore point between himself and John Dustin Archbold and that he wanted her to investigate it thoroughly. He had the testimony in court; it took him months to get them. He was obsessed with the idea that the lawyers were in cahoots with the court because of the high success fee, especially since two of the lawyers later became judges. Ida Tarbell had her recording - because the 60-page document remained in the office - checked by lawyers who, however, saw nothing unusual in it. Contrary to her usual practice, she even sent Rogers a copy of her intended presentation. Rogers also arranged for her to meet with Henry M. Flagler . However, he evaded her questions about the South Improvement Company and instead told of the beginnings in Cleveland. A conversation with Rockefeller was also not in sight. The first episode of their "History" came out in November 1902, and although Rogers had noted that it was trying to prove that the Standard Oil Company was just a continuation of the South Improvement Company with its railroad discount systems and elimination of competitors, all he said was that their expression is sometimes a little bare. There was then no discussion with Rogers about Vacuum Oil / Buffalo because Ida Tarbell had in the meantime received accounting documents from a refinery operator who believed her to be trustworthy, which clearly showed that employees of the railway companies owned the South Improvement Company about the shipments informed the competition, which was then misdirected and reached the port too late. She now held the missing evidence on previous charges against Standard. To protect her informant, she gave fictional names and locations in the publication. The issue had just appeared when Ida Tarbell asked Rogers whether this espionage practice had been pursued afterwards. Rogers was very angry and wanted to know her source, which she of course did not reveal. All she told him was that he had always denied espionage, but that he knew full well that her records were genuine. Rogers was later suspected of having given these documents to Ida Tarbell himself. The series was published in twenty articles in McClure's Magazine from November 1902 to July 1903 and December 1903 to October 1904. The chapters of her later book in two volumes deal with:

- The Birth Of An Industry

- The Rise Of The Standard Oil Company

- The Oil War Of 1872

- "An Unholy Alliance"

- Laying The Foundations Of A Trust

- Strengthening The Foundations

- The Crisis Of 1878

- The Compromise Of 1880

- The Fight For The Seaboard Pipe-Line

- Cutting To Kill

- The War On The Rebate

- The Buffalo Case

- The Standard Oil Company And Politics

- The Breaking Up Of The Trust

- A Modern War For Independence

- The Price Of Oil

- The Legitimate Greatness Of The Standard Oil Company

- Conclusion

Both volumes contain extensive appendices with documents. In the foreword to a new edition of her book from 1925, Ida explains the reasons why she chose the “Standard Oil Company”.

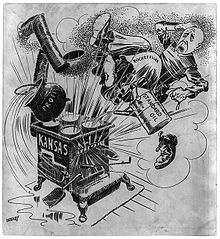

John D. Rockefeller - a character study

In the editorial office, they persuaded Ida Tarbell that she now had to write about Rockefeller herself, who was previously unknown to her personally. She was advised to attend a Sunday service at Rockefeller's Church on Euclid Avenue, Cleveland, where he spent the summer. Ida Tarbell was not known here. Her first impression was that of a very old man (Rockefeller was 64 in October 1903) and at the same time of power. At church he exchanged his hat for a cap and Ida Tarbell describes his expression very precisely, which George Varian captured in his drawing. Noticeable were Rockefeller's eyes, which were never calm, but hurried from face to face. When he spoke at Sunday School, his voice was clear and convincing. In the service that followed, the congregation's attention was obviously more focused on him than the pastor.

It divides the character study into two parts. Part I begins with the family story of his brother Frank and his friend James Corrigan, which Frank told Ida Tarbell personally and was deeply bitter about it. She took this as an opportunity to exemplify John Davison's business practices. Part II first describes Tarbell's personal impression of Cleveland in 1903, best captured by Varian in his drawing by J. D. Rockefeller. She then examines the discrepancy between religion, charity, and Rockefeller's business practices.

Standard Oil Company in Kansas 1905

In 1905 Ida Tarbell traveled to Oklahoma and Kansas, where the history of Pennsylvania seemed to repeat itself. Standard Oil worked to manipulate competition in the Kansas oil market by securing better freight rates and refusing to make its pipeline available to all producers. Producers suffered a rapid and dramatic fall in the price of crude oil resulting from high inventory levels and the lack of purchases by competitors. Consumers had to pay high prices for the kerosene. Standard controlled the Kansas oil market and everyone else suffered the effects. Investors, resellers and consumers protested loudly because it was an election year and political solutions were hoped for. Standard Oil had just laid the pipelines to the Sugar Creek Refinery near Kansas City, Missouri, which opened in 1904.

Startled by this monopoly, the "Oil Producers' Association" organized in Peru in January 1905 with H. E. West as president. Just a week later, the oil producers traveled to Topeka by special trains . Here they worked out a resolution that they presented to Governor Edward W. Hoch :

- Establishment of a state oil refinery

- Making Pipelines a Public Transportation Company

- An anti-discrimination law with a ban on undercutting competitors in order to ruin them and then selling the product elsewhere at inflated prices

- Determination of maximum freight rates in rail transport

- a supervisory authority for the oil fields and protection against neglected or abandoned oil wells as well as supervision, investigation and classification ("grading") of crude oil.

Ida Tarbell arrived in Topeka when the bill was due to be presented to the House of Representatives. The oil producers had just called on the population to get their MPs to approve. But the lobbyists also worked for Standard Oil. A state-owned refinery posed no threat to them, but they feared the accompanying drafts that resulted in free trade for all. As a further step, Standard stopped all work on the pipelines and tanks. The angry workers rallied in Bartlesville, Cleveland, Oklahoma, Independence, and Chanute. Standard Oil boycotted the purchase of oil in Kansas. The independent oil producers then sent a telegram to President Roosevelt on February 15, 1905 . On February 20, the president ordered an investigation into the oil boycott. The Inter-State Commerce Commission began its investigation in Kansas on March 13, 1906.

Despite - or perhaps because of - the excitement, Parliament in Topeka passed all proposals as laws - with the exception of No. 5. An oil field inspector was not appointed by the state until 1913. The Kansas oil producers had realized that their problems also affected neighboring states and that they had to find not only national but also international markets for their oil. The railroads appeared accommodating after the Chautauqua County's attorney general indicted the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe railroads in 1905 for violating anti-trust laws. Soon two large foreign refineries and competitors of Standard showed their interest because the Kansas oil reserves were of good quality and low in sulfur.

Muckraker

Ida Tarbell's story about Standard Oil was a feat. Her persistent research, meticulous attention to detail, and uncompromising commitment to the truth exposed the illegal machinations of the Rockefellers Trust. The story quickly became the hallmark of investigative journalism. In 1897, Ray Stannard Baker joined McClure's and Lincoln Steffens , whom Ida Tarbell described as the “most brilliant addition”. An angry and irritated President Roosevelt, in a 1906 speech, compared this new generation of writers and journalists to John Bunyan's (1628–1688) book of edification, The Pilgrim's Progress , in which the man with the muck rake neither looks up nor the crown that looks up he is offered in exchange for his rake, but continues to rake up the dirt on the ground. You should also look up and share the good. If the whole picture is painted black, then there will be no shade left with which one can distinguish the villains from their fellow men.

What sparked the president's anger was David Graham Phillips' 1906 Cosmopolitan series The Treason of the Senate , which described the lives and careers of 21 senators in a drastic manner.

Ida Tarbell had hoped her story about Standard Oil would be seen as a historical study in which she had compiled facts. To her dismay, she and her colleagues, Baker and Steffens, as well as other writers like Frank Norris and Upton Sinclair, have been referred to as " Muckraker " and social reformer. Rockefeller is said to have called her "Miss Tarbarrel" (tar barrel).

President Roosevelt, however, kept his promise to crack down on the trusts. In November 1906, the federal government brought charges against Standard Oil for obstruction of international trade, a violation of the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890.

New beginning: The American Magazine 1906–1915

In early 1906 McClure came back from Europe with new ideas. Without consulting his partners - including John Philips - he founded a new company. This should not just publish a new magazine, the McClure's Universal Journal , but a bank, an insurance company, a school book publisher and a housing association for inexpensive houses on the market. He was obsessed with his idea and deaf to all arguments. When he asked Ida Tarbell for her cooperation, she flatly refused, even though it was very painful for her after 12 years. When McClure couldn't convince John Philips either after a tough struggle, he finally paid him off. Without Philips, the employees could not imagine their work at McClure, so she left the magazine together with Ray Stannard Baker, Lincoln Steffens, John Sidall and the managing director Albert Boyden in March 1906.

The owner of The American Magazine (formerly Frank Leslie's Illustrated Monthly ), Frederick L. Colver, offered John Philips his magazine for sale. All brought in some money and convinced other friends to participate. In the beginning, a salary - as McClure had paid - now had to be enough for two employees. They had adjusted their standard of living accordingly and viewed it as an adventure; this resulted in a fruitful and professional camaraderie. The first edition of The American Magazine appeared with the newly founded "John Philips Publishing Company" in October 1906. During this time they also gained two new employees, Finley Peter Dunne and William Allen White , who came to them from Kansas.

The American Magazine was designed to be less exciting. The aim of the new magazine was "interesting and important for the public, but ... also the most touching and delightful monthly book of fiction, humor and a feeling for a happy read". It was designed to be friendlier and more amiable. As a result, he lacked the focus, the bite, the power that McClure's possessed.

She also changed in her private life. Ida Tarbell, now 49 years old, bought an old farmhouse in Easton, Connecticut in 1906 which she called "Twin Oaks" and where she would live and work until her death in 1944, first with her niece Esther and later with her sister Sarah. Mark Twain had built a fantastic house about 15 km away, and since he loved big parties, he invited everyone to it, including Ida Tarbell.

In 1909, Ida Tarbell wrote a series about women who campaigned against slavery before and during the American Civil War , including Mercy Warren, Abigail Adams , Esther Reed, Mary Lion, Catharine Reecher, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Susan B. Anthony .

Ida Tarbell's first political contribution came after the signing of the Payne-Aldrich Act by President Taft in August 1909. It set the tax and customs tariffs and again showed protectionism towards the coal and steel industries. There had been heated debates between "insurgents" (progressives) and "standpatters" (conservatives) in both Congress and Senate. On July 30th, the House of Representatives passed the Payne-Aldrich bill with 195 to 183 votes; H. 20 Republicans had voted against with the Democrats. On August 5, the Senate passed the bill with 47 votes to 31, with ten more “no” votes from Republicans. There had never been so many rebels within their own party who publicly expressed their displeasure. Her articles, The Mysteries and Cruelties of the Tariff , appeared in Nov, Dec 1910, Jan 1911 and Testing the Tariff by Moral Effects , June 1911. In Ida Tarbell's view, these tariffs were also a trust and were published in her 1911 book The tariff in our times she traces the history of tariffs since the civil war.

An article in the Herald Journal from April 1911 has survived in which Ida Tarbell asks whether American society wants to continue to be governed by politicians in which a few distribute power and capital among themselves and therefore do not want change (The Stand-Pat Intellect) or whether they don't want a fairer society after all.

Now she wanted to form her own picture of the effects of the tariffs on the factories and on the workers in her country, and so between 1912 and 1915 she visited many agricultural and industrial companies all over America. She had now met Frederick W. Taylor and had even written down some of his rules for herself. She immediately noticed in the factories where he had been active or where his rules were being worked. She was also impressed by Henry Ford's methods. She processed her experiences in her book New Ideals in Business, an account of their practice and their effects upon men and profits , published in 1916. She also wrote biographies of two managing directors: Elbert H. Gary of US Steel and Owen D. Young of General Electric.

In 1913 she picked up the pen again and wrote in The American her article The Hunt for The Money Trust about the "Pujo Committee" named after Senator Arsène Pujo , which from May 1912 to January 1913 investigated the relationships between the Northern Securities Company by John Pierpont Morgan , who, along with railroad moguls James J. Hill and Edward Henry Harriman, controlled most of the traffic and had interests in a number of other companies through his National City Bank and Chase National Bank . Ida Tarbell's motivation for this article was to demystify the so-called pujo investigation and to present the events in their process in such a way that even the average citizen could understand them. She argued that the existing financial system was placing too much power in the hands of a small group of bankers out of touch with the average American. From 1913 Ida Tarbell was president of the Pen and Brush Club , an organization for women artists and writers, for 30 years .

Interview with the New York Times in 1916 about the commercialization of writers

In 1916 Ida Tarbell gave an interview to the New York Times about the commercialization of American literature. The reporter valued her opinion as she was both a writer and a magazine editor. She explained it this way: A young writer gets about $ 300-400 for his first article. The magazine publishes more articles because it sees his talent. Readers like his stories too, and he becomes known. Now the competition begins among the magazines that offer him a fee of perhaps $ 1000 to $ 1500. The author is happy and sees it as recognition of his work. But then you ask him to write a story every month for a year and he goes into literary prostitution, because no one can do that, whether young or experienced. Ida Tarbell firmly rejected the reporter's question as to whether this was not the fault of the magazines. Nobody forced the author to accept the offer. It was his choice. He gave in to his wishes or needed money. He sacrifices his talent in favor of a limousine or fancy apartments. He alone is guilty.

“We writers are not babies, who must be shielded from the world, we are men and women, and we must act like men and women! We don't need protection from designing publishers any more than the writers of bygone generations did. "

“We writers are not babies to be protected from the world, we are men and women and we have to act like men and women. We do not need protection from scheming publishers any more than the writers of previous generations. "

No publisher took her by the throat and forced her to become her slaves. They liked to come, attracted by the promise of "big money". They knowingly sold themselves into addiction. A writer should be smart enough to know that he doesn't have to make $ 10,000 a year. He doesn't really need a limo. He could be just as happy and maintain his self-respect driving a Ford or even the subway.

Ida Tarbell then cited Finley Peter Dunne as an example, who impressed her very much. He wrote eight or ten episodes of his Mr. Dooley stories and then again nothing for a whole year. He could have made a lot of money writing his stories month after month and year after year, but he knew it would be superficial work. However, he is a thorough and responsible author who also throws in the trash a lot that he does not consider to be successful. He believes in the old adage "easy writing is hard reading" and she has great respect for his attitude.

Freelance journalist, interview with Mussolini

Over the years, the nature of "muckraking" journalism had changed. The publishers mainly looked at the number of copies. But the approaching First World War also forced a new way of writing. It became a serious question whether an independent journal like hers could survive under the changed circumstances, the intellectual and financial uncertainties, especially since it had no financial backing. Lincoln Steffens had left it soon after it had started because he did not want to submit to the editing of his articles - although this was already common practice at McClure's. Ray Stannard Barker also pursued his own interests more and more. In the end they sold The American to the Crowell Publishing Company in 1915 , and only John Sidall wanted to take on the new role as editor. He soon made his mark on it and the new magazine became a commercial success.

Ida Tarbell soon missed her office in the editorial office and the exchange with her colleagues. Now she worked at home alone in her study. So the offer from Louis Alber from the Coit-Alber Lecture Bureau, which organized lectures and lectures as part of the Chautauqua movement, came at just the right time. It was a new challenge for Ida Tarbell, so she took speaking lessons from Franklin Sargent of the American Company of Dramatic Art . She spoke about unemployment, the American economy and its future, Frederick Taylor's new management methods and, increasingly, about the impending war.

In 1916 she was invited to a Cabinet Dinner at the White House and met Woodrow Wilson and his wife personally. He offered her to work in his new Federal Tariff Commission, which she refused because she believed that journalists should observe politics from the outside. She also refused to take part in a trip to Stockholm on the peace ship organized by Henry Ford. Even Jane Addams , who was very ill and therefore not on board, could not convince Ida Tarbell of this idea because she said that America would eventually go to war.

She was also appointed by telegram from President Wilson to serve on the Women's Committee of the Council for National Defense, under the direction of Anna H. Shaw . They were under the Ministry of Defense and were supposed to take care of the interests of women. The men were drafted into the army and the women had to be trained to take their places in industry. Jane Addams said that while this set back social achievements by decades, Ida saw it as an opportunity for women to get an education.

From 1916, Ida Tarbell's health began to deteriorate when she was first diagnosed with tuberculosis and then Parkinson's disease. However, that didn't stop her from doing her job and she even learned to write with a typewriter.

In 1919 she was in France as an observer for Red Cross Magazine , published by John Philips, and described her findings on weapons of mass destruction and the devastation in Europe after the war. They expected her to make a monthly contribution. The RC maintained warehouses of clothes and knitwear made by American women across the country. Ida Tarbell chose Lille as her headquarters and reported on the situation in the former theaters of war in northern France and Belgium. She also wrote about the Paris Peace Conference and the hopes of the various groups. Here she met many former journalist colleagues who had meanwhile achieved important positions, including Ray Stannard Barker, the official press spokesman for the American delegation.

Also after the war, she appointed President Wilson and three other women delegates to the Industrial Conference, which was supposed to work out proposals for employers (here it was the railroad) and employees - the forerunner of the later union. She was then a member of the Unemployment Conference under President Warren G. Harding , although she did not appreciate him.

In 1922 she was an observer of the Naval Disarmament Conference in Washington DC, which ended with the Disarmament Treaty of February 6, 1922 . Ida Tarbell described the negotiations in her book: Peacemakers, blessed and otherwise: observations, reflections, and irritations at a National Conference .

Ida Tarbell did not believe that democracy had to be replaced by socialism or communism or a dictator when she was asked to go to Italy in 1926 to report on the fascist Benito Mussolini , who has been in power for four years. She was amazed that he got into government without bloodshed. Maybe there she could learn how to handcuff a free government. The main reason for her trip, however, was that she had been offered such a large sum that she ultimately won over. Even in Paris, she regretted accepting the job when a good friend told her that she would be searched and advised her not to take any books, newspapers or letters to opposition parties with her, not to speak French and to practice the fascist salute. She traveled to Turin and Florence, to San Marino and Calabria to Palermo. The people were not really satisfied with Mussolini's rule, but it was always better than anarchy . Back in Rome, she worked in the American embassy on questions she wanted to ask Mussolini. The ambassador, Henry P. Fletcher , recommended that she just have a chat with him. She talked to Mussolini for half an hour in French about housing problems, drinking habits in Italy, and alcohol in the United States. The comparison with Napoleon Bonaparte came to her involuntarily. She wondered whether Ethiopia and the alliance with France and the rebels in Spain meant to Mussolini what Spain and Russia once were to Napoleon. On the way back she read about the attempted assassination attempt by Anteo Zamboni on October 31, 1926 on Via Riccoli in Bologna. The shots missed the dictator and the assassin was immediately attacked and lynched by nearby fascists.

Appreciation

Even today she is considered the first woman to stand up against corruption and, as a journalist, to challenge and win the Standard Oil Group. Together with her colleagues and employees, journalism led her there, which is now called "investigative". Almost 50 years later, the “ Spiegel Affair ” of 1963 for Germany or the “ Watergate Scandal ” for America , which was uncovered by the Washington Post in early 1972, are comparable .

Of all the books and articles Ida Tarbell has written in her life, the one she was most proud of was The History of Standard Oil . She harbored a deep dislike for the term "Muckracker". In an article she wrote, Muckraker or Historian, she justified her efforts to expose the machinations of the Oil Trust and mentioned “this classification as Muckraker, which I disliked. This whole radical element, which I counted many friends among, begged me to join their movements. I soon found out that most of them were open to attack. They had little interest in balanced results. Now I was convinced that in the long run the public who wanted to stir it up would get tired of the abuse that if one wants to achieve lasting results, the spirit must be convinced. "

In 1999, The New York Times her work The History of the Standard Oil as No. 5 among the top 100 works by American journalists of the 20th century.

Ida Tarbell died of pneumonia in Bridgeport, Connecticut Hospital. She was buried with her family in Titusville.

In 2000, Ida Tarbell was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame in Seneca Falls NY.

Works

- All in the day's work: an autobiography . 1939

- The Nationalizing of Business . 1878-1898. Macmillan, New York 1936

- A reporter for Lincoln; story of Henry E. Wing, soldier and newspaperman . 1927

- The Life of Elbert H. Gary: The Story of Steel . Appleton, New York / London 1925

- He knew Lincoln, and other Billy Brown stories . 1922

- Peacemakers - blessed and otherwise; observations, reflections and irritations at an international conference . 1922

- Boy scouts' life of Lincoln . 1921

- The rising of the tide; the story of Sabinsport . Macmillan, New York 1919

- In Lincoln's chair . 1920

- New ideals in business, an account of their practice and their effects upon men and profits . Macmillan, New York 1916

- The ways of woman . Macmillan, New York 1915

- The tariff in our times . Macmillan, New York 1911

- Father Abraham . 1909

- Abraham Lincoln, an address delivered by Miss Ida Tarbell for the Students' Lecture Association of the University of Michigan. 1909

- He knew Lincoln . McClure, Phillips New York 1907

- Madame Roland: a biographical study . Scribner's, New York 1905, 1916

- The history of the Standard Oil Company . McClure, New York 1905, 1912, 1950

- The life of Abraham Lincoln . 1900, 1903, 1909, 1917, 1920, 1924, 1928

- A life of Napoleon Bonaparte: with a sketch of Josephine, Empress of the French . 1901, 1909, 1919

- The early life of Abraham Lincoln . 1896

- A short life of Napoleon Bonaparte . McClure, New York 1895

- Books by Ida Tarbell in the Internet Archive

Further reading and newspaper articles

- Robert C. Kochersberger (Ed.): More than a Muckraker: Ida Tarbell's Lifetime in Journalism . University of Tennessee Press, 1996.

- Jane Jerome Camhi: Women Against Women: American Anti-Suffragism , 1880-1920. Carlson Pub., Brooklyn NY 1994

- John Satter: Journalists Who Made History. Minneapolis . The Oliver Press, MN 1998

- Ellen Frances Fitzpatrick: Muckraking: Three Landmark Articles . Bedford Books of St. Martin's Press, 1903. New edition: Bedford Books, 1994, ISBN 978-0-312-08944-3

- Judith and William Serrin: Muckraking! The Journalism that Changed America. The New Press, New York 2002, ISBN 978-1-56584-681-4 .

- Kathleen Brady: Ida Tarbell. Portrait of a Muckraker. With literature and index. With a foreword by the author. Putnam 1984, ISBN 978-0-399-31023-2 ; University of Pittsburgh Press, 1989.

- Barbara A. Somervill: Ida Tarbell: Pioneer Investigative Reporter (World Writers). M. Reynolds, ISBN 978-1-883846-87-9

- Steve Weinberg, Taking on the Trust: How Ida Tarbell Brought Down John D. Rockefeller and Standard Oil . WW Norton & Company 2009. ISBN 978-0-393-33551-4

- Ann Bausum: Muckrakers: How Ida Tarbell, Upton Sinclair, and Lincoln Steffens Helped Expose Scandal, Inspire Reform, and Invent Investigative Journalism . National Geographic Children's Books 2007. ISBN 978-1-4263-0137-7

- MISS TARBELL'S BOOK. A Glance at the Widely Advertised "History of the Standard Oil Company." (PDF) In: New York Times , December 31, 1904

- Garfield Makes Reply to Critics of Report; Quotes His Report in Refutation of Oil and Railroad Officials. Contradicts HH Rogers Answers Denials with Revelations of Blind Billing - Missive Made Public by Mr. Roosevelt . (PDF) In: New York Times , May 18, 1906

- The Standard Oil Report. Nearly three years ago, Miss IDA M. TARBELL published her two-volume "History of the Standard Oil Company." Yesterday the Inter-State Commerce Commission sent to Congress the report it had prepared in obedience to the Tillman-Gillespie resolution of last March . (PDF) In: New York Times , January 29, 1907

- Twelve Greatest Women; Composite List From One Hundred Who Have Been Nominated for Honor . (PDF) In: New York Times , June 25, 1922

- Women: The National League . In: Time Magazine , April 14, 1923

- Ida M. Tarbell, 86, Dies in Bridgeport . In: New York Times , January 17, 1944

- Comparison of Tarbell from History of Standard Oil 1904 and John D. Rockefeller from Reminicences of Men and Events 1909. (PDF; 702 kB) National Humanities Center

Web links

- Ida Tarbell. In: FemBio. Women's biography research (with references and citations).

- History of Standard Oil . LibriVox recording, read by Tom Weiss (English): Volume 1 / Volume 2

Individual evidence

- ↑ The Panic of 1857

- ↑ The Tarbell House in Titusville ( Memento of the original from September 11, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 320 kB) History of the Oil Region Alliance

- ↑ Harper's New Monthly Magazine

- ↑ Popular Science Monthly . In: Encyclopædia Britannica Online

- ^ Tarbell: All in The Day's Work . P. 48 ff.

- ^ The Rev. Theodore L. Flood. The New York Times, June 27, 1915

- ↑ The Chatauquan April 1897-September 1897. Volume XXV - New Series Volume XVL

- ↑ Ida Tarbell and "The Business of Being a Woman"

- ↑ All in a day's work , p. 90

- ↑ All in a day's work , p. 97

- ↑ France Adoree Scribner, May 1892

- ↑ All in a day's work , p. 99

- ^ Madame Roland Scribners , November 1893

- ↑ All in a day's work , pp. 114-115

- ↑ Gettysburg Compiler of June 14, 1892 .

- ^ All in a day's work , p. 118.

- ^ Pierre Janssen ( Memento of December 10, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ A Chemical Detective Bureau: The Paris Municipal Laboratory and What It Does for the Public Health . In: McClure’s , July 1894

- ^ Pasteur at home . In: McClure’s , September 1893

- ↑ Clos de la Platière Résidence de MMe Roland ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Cartes Postales 1900

- ↑ All in a day's work , p. 136 ff.

- ^ All in a day's work , p. 141.

- ↑ Madame Roland. A Biographical Study . Charles Scribner's Sons, New York 1896

- ^ Gardiner Greene Hubbard Collection in the Library of Congress

- ↑ Charles Joseph Bonaparte ( Memento of the original from April 8, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ All in a day's work , p. 150 ff.

- ^ McClure's January 1905

- ↑ John Nicolay (1832-1901)

- ^ All in a day's work , p. 163.

- ↑ Abraham Lincoln, bust-length portrait, facing right Published in McClure's, October 1895.

- ↑ Carl Schurz: “Reminiscences of a long life” . In: McClure's Magazine , March 1906 issue

- ↑ Mabel K. Clark: Ida Tarbell . ( Memento of the original from July 2, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. In: Historic Pennsylvania Leaflet No. 22nd

- ^ The Story of the Declaration of Independence McClure's, July 1901 issue

- ^ The Trial of Aaron Burr . In: McClure’s , March 1902 edition

- ↑ All in a day's work , p. 211

- ↑ All in a day's work , p. 214

- ^ Yaw Yeboah: The Dragon Slain: The Breakup of the Standard Oil Trust . Professor and Head, Department of Energy and Mineral Engineering, College of Earth and Mineral Sciences, The Pennsylvania State University.

- ↑ a b All in a day's work , p. 220

- ↑ All in a day's work , p. 225

- ^ History of the Standard Oil Company . In: McClure's Magazine , November 1902 issue

- ↑ All in a day's work , p. 227

- ^ The history of the Standard Oil Company - Preface

- ↑ All in a day's work , pp. 235-236

- ^ All in a day's work , pp. 237-238

- ↑ John D. Rockefeller: A Character Study - Part I. In: McClure's Magazine , July 1905 issue

- ↑ John D. Rockefeller: A Character Study - Part II. In: McClure's Magazine , August 1905

- ^ Kansas and the Standard Oil Company, Part I - A narrative of today . In: McClure's Magazine , September 1905

- ^ Sugar Creek Refinery

- ^ Kansas and the Standard Oil Company, Part II - A narrative of today in: McClure's Magazine, October 1905

- ^ Kansas Oil Producers appeal to President . In: The Desert News , February 15, 1905

- ↑ STANDARD OIL BOYCOTT SHUT OUT INDEPENDENTS; Tore Out Pipe Lines and Put Screws on Roads, Witness Says. OIL 52C .; FREIGHT RATE 57C. Freight Agent of the M., K. & T. Admits Standard's Man Was Present When Roads Raised Rates. In: The New York Times , March 13, 1906

- ↑ All in a day's work , p. 198 ff.

- ↑ Definition muckrakers in: info please.

- ↑ STANDARD OIL CO. TO BE PROSECUTED; Roosevelt Decides to Bring It to the Criminal Bar. SPECIAL COUNSEL EMPLOYED Will Start Rebate and Anti-Trust Suits at Once - President and Cabinet Fully Agreed . The New York Times , June 23, 1906

- ↑ All in a day's work , pp. 254-260

- ↑ The American Magazine - Some issues with a table of contents ( Memento of the original from November 10, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ CT National Historic Landmark # 4 Ida Tarbell House, Connecticut

- ^ Ida Tarbell: The American woman. Collection from "The American Magazine" Portraits collected by Charles Henry Hart

- ^ The tariff in our times. The Macmillan Company 1911

- ↑ Ida Tarbell: What our country is facing . In: Herald-Journal , April 9, 1911

- ↑ MONEY TRUST HUNT TURNS TO INSURANCE; Effort by Untermyer to Show Perpetual Control in the Interest of Leading Financiers. Special to The New York Times. January 08, 1913

- ^ Pen + Brush History. In: penandbrush.org. October 23, 2005, accessed May 10, 2020 .

- ↑ Our Rich Authors Make Cheap Literature; Ida M. Tarbell Laments Tendency of Some of Our Modern Writers to Sacrifice Their Independence and Self-Respect for the Sake of High Prices

- ↑ The American Magazine - Some issues with a table of contents ( Memento of the original from November 10, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Documents on Coit-Alber Chautauqua Co. in the documents of Allegheny College

- ↑ Ford Peace Ship ( Memento of the original from January 19, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Red Cross Magazine

- ^ Proceedings of the first Industrial conference (called by the President) October 6 to 23, 1919 Ed. Department of Labor. Govt. printing office Washington, 1920 - participants p. 6ff.

- ↑ The Washington Naval Treaty 1922

- ↑ All in a day's work , pp. 378-384

- ^ Ida Tarbell Pioneering Oil Industry Journalist

- ↑ Tarbell in National Women's Hall of Fame, Seneca Falls NY

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Tarbell, Ida |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Tarbell, Ida Minerva |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American writer and journalist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | November 5, 1857 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Hatch Hollow |

| DATE OF DEATH | January 6, 1944 |

| Place of death | Bridgeport |