History of the Jews in Libya

The history of the Jews in Libya began in the Greek Kyrenaica around 2500 years ago. It has left its mark on the Bible and was shaped by the Puners , Romans , Berbers , Vandals , Arabs , Turks and Italians in changing rulers over Libya . After the establishment of the State of Israel , 32,000 Jews were displaced between 1949 and 1951 , which was 90% of their community. In the wake of the Six Day War , the majority of the remaining Jews were evacuated, and under Muammar al-Gaddafi , the last remaining Jewish woman moved to Rome in 2003 . Libyan Jews and their descendants now live mainly in Israel , but also in Italy.

antiquity

Cyrenaica

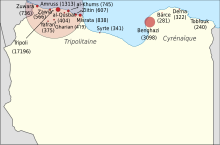

The Cyrenaica , so today's East Libya, was from the 7th century BC. Settlement area of the Greeks and soon had a large Jewish population. Probably the oldest Hebrew inscription in Libya is the name of the owner on a seal stone that was found in the city of Cyrene , the center of the Greek settlement area. It could only be roughly dated between the tenth and fourth centuries BC. From the first century BC A grave stele, exhibited in the small museum of Marsa Susa on the outskirts of ancient Apollonia , the former port of Cyrene, with the names and ages of three people from a Jewish family comes from the 4th century BC . Other similar finds show that there were Jewish communities in all five cities of the Pentapolis .

According to Flavius Josephus , the oldest Jewish diaspora communities in Libya go back to the Diadoch Ptolemy I (305–285 BC). He is said to have settled Jews from Alexandria in Cyrene and other cities in Eastern Libya in order to have this area of his empire better under control. From their widespread use and their influence in the Cyrenaica, the 74 BC. According to Flavius Josephus, quoting the Greek historian Strabo (approx. 63 BC to 23 AD): “In the city of Cyrene there were four classes: citizens, peasants, Metoks and Jews . They have already come to every city, and it is not easy to find a place in the world that has not adopted this sex and is occupied by it. ”However, at the time of Strabon, the Jews in Cyrenaica were so harassed and harassed by their Greek neighbors robbed that Emperor Augustus had to strengthen their position by decree. He confirmed the right of the Jews to freely practice their religion, expressly allowed the transfer of temple funds to Jerusalem and declared that their theft should be punished as temple robbery.

After the first great uprising of the Jews in Palestine was suppressed by Titus and the Temple of Jerusalem destroyed in AD 70, a sicarian tried in Cyrene in 73 vain to resume the fight against the Romans. Great devastation and a high blood toll - the historian Cassius Dio speaks of over 200,000 Romans and Greeks killed - was the result of the Jewish diaspora uprising that started in 115 in Cyrene. His overthrow required great military efforts from the Romans and ultimately decimated the Jewish population in Cyrenaica, Cyprus and Egypt . At Hadrian's reconstruction of the city of Cyrene after this Tumultus Judaicus remember more preserved today Latin inscriptions .

Important sources on community life in Kyrenaica are the Greek inscriptions of Berenike ( Euhesperides ), today's Benghazi , which were made in the early Roman Empire . The younger of two honorary decrees of the city's Jewish Politeuma dates from AD 24/25. According to the inscription, it was placed in a prominent place in the city's “ amphitheater ” and thanks the Jewish community to the Roman prefect Marcus Tittius for his humane treatment with the Jews expression.

Cyrene in the Bible

The existence of Jewish communities in Cyrenaica can also be read from the Bible. An author Jason of Cyrene appears in the Apocrypha , whose five-volume historical work, which has not been preserved, formed the basis for the Second Book of the Maccabees . It supplements the reports contained in the First Book of the Maccabees on the Jewish struggle for freedom against the Seleucids (167–142 BC). The addressees of a circular from the Roman Senate in favor of the Jews of 139/138 BC BC mentioned in the First Book of the Maccabees belongs to Cyrene.

Cyrene is also mentioned several times in the New Testament. For example, a man named Simon of Cyrene , possibly a Jerusalem-based Diaspora Jew from Cyrenaica, is forced by Roman soldiers to carry the cross of Christ. And the Acts of the Apostles shows that Diaspora Jews from Cyrene had their own synagogue in Jerusalem .

Tripolitania

It is not unlikely that Jews settled as early as 813 BC. In the wake of the linguistically related Phoenician settlers along the North African coast. Secured Jewish traces from pre-Roman times are practically non-existent west of the Cyrenaica. In Tripolitania , which belonged to the newly created Punic cultural area with the center of Carthage , there were large numbers of Jewish immigrants from 70 AD after the destruction of the Temple of Jerusalem . Waves of immigration are also likely to have triggered the suppression of the diaspora uprising and the Bar Kochba uprising . Evidence of Jewish communities was found in Leptis Magna and Oea, today's Tripoli .

Carthago, in neighboring Tunisia, must have had a strong attraction for Jewish traders and settlers. After the total destruction of the Punic metropolis in 146 BC. It was first rebuilt by Emperor Augustus and made it the capital of 27 BC. BC formed the province of Africa proconsularis . The large necropolis from the first to fifth centuries, found on the northwestern outskirts of Carthago under the Gammarth Hill, contains numerous Jewish sliding graves . A current compilation of the archaeological facts and their neutral analysis highlights the strong local (North African) character of the burial culture observable in Gammarth and questions the degree of Talmudic influences.

Even the early Christian writer Tertullian (approx. 150–230 AD) reported from Carthage about missionary activity of the Jews, and the Islamic historian Ibn Chaldun (1332–1406) mentions in his work on the history of the Berbers that this was before of the Muslim conquest were partly of Jewish faith. The explicitly named tribes include not only the Jarawa from the Aurès with their famous leader al-Kahina , but also the "Nefouca, Berbers from Ifriqiya," . Ifrīqiya is the medieval name for the area of the Roman province Africa proconsularis, which also includes Tripolitania, and the Nefouca share their name with the Nefusa Mountains , which rise behind the flat coastal zone of Tripolitania. The much older theories cited by Ibn Khaldun about the ancestry of the Berbers from immigrants from Palestine should, however, belong in the category of legends.

Over the centuries, the indigenous Berbers had come close to the Semitic Phoenicians and Jews in language and religious beliefs . But Jews who lived in the hinterland of Libya also adopted Berber customs.

Late antiquity

Already in the classical Roman Empire , Libya was an important target of the first Christian missionary work because of its Jewish communities and the short distance to Palestine , which competed with Jewish conversion efforts. The North African Christian leaders therefore fought the Jews, for example the church father Tertullian from Carthage with his pamphlet Adversus Judaeos . The conflict remained without major consequences as long as the Roman emperors, for example Septimius Severus , who came from Tripolitania, and his son and successor Caracalla persecuted the Christians and continued to treat the Jews as privileged. The situation changed, however, when Constantine the Great promoted Christianity with the Milan Agreement from 313 and this became the state religion from 380. Constantine's successors worsened the legal congestion of the Jews with council decisions and laws. For example, in AD 388, marriages between Christians and Jews were banned.

The border that arose between the two Roman empires when the empire was divided in 395 AD ran through the middle of Libya. After the invasion of the Vandals , who made Carthage their capital in 439, the west of Libya remained part of the Vandal Empire for a century. It can be assumed that the Arian Vandal rulers were more tolerant of the Jews than the Christian emperors before them. The reconquest of Libya by Justinian I brought the country not only its brisk building activity, which Prokop describes in his book de aedificiis , but also its radical Christianization policy, the "idolaters" and the baptized who "live on with the error of the pagans" threatened the death penalty. In addition, the governor of Africa was commissioned to convert all synagogues as well as the churches of the Arians and the Donatists into churches of orthodox believers. However, this amendment was not implemented because of the unstable situation in the region. However, the historian Prokop reports of an exceptional case: Justinian imposed a conversion to Christianity and the conversion of the synagogue into a Christian church on the Jewish community Borieum (also Borion ) on the western edge of Cyrenaica - even though the old tradition existed in the community their synagogue was built by King Solomon .

Arab and Turkish rule

When North Africa was conquered by the Arabs , Cyrenaica in 643 and Tripolitania in 647 were occupied and the country was Islamized. After years of Eastern oppression , the vast majority of Jews probably welcomed this upheaval. Despite changing Arab dynasties several times, their dhimma status, which discriminated against them but at least allowed them to practice their religion, was able to get along well with Muslim rulers for centuries. An exception was the rule of the Almohads , who advanced as far as Tripolitania and Spain and harshly persecuted Jews and Christians alike.

Under Caliph Muawiya I (661–680), the founder of the Umayyad dynasty, the Arab world was transformed into a secular state. Muawiya saw the Jews as loyal allies and encouraged their settlement in Tripoli. In the Abbasid period , Jews were heavily involved in long-distance trade, and Jewish settlements along the east-west trade route through Libya were a strategic advantage. In neighboring Tunisia , the Jewish community of Kairouan developed into an important center of the Jewish world during the Shiite Fatimid era . In the dispute between the yeshivot of Palestine and Baghdad for dominance in North Africa, Rabbi Scherira Gaon wrote his historically important letter to the Jews of Kairouan in 987.

A letter from Maimonides (c. 1135–1204) suggests that Jewish life in Libya did not flourish in the Golden Age as it did in the rest of the Maghreb and Spain . In it he recommended to his son that he should avoid contact with Jews west of Djerba . They are ignorant and have unusual customs. In fact, the frequently changing rule over the coast and nomadic raids from the hinterland may have hindered contact between the Jewish communities in Libya and their western neighbors.

The Cairo Geniza also provides information about the life of Libyan Jews . For example, letters from the 11th century report on an exchange of goods between Sicily and Tripoli on the eve of the end of Islamic rule over Sicily . Even after the Reconquista, Tripolitania was an important refuge for the Jews, who had experienced a long period of cultural bloom on the Iberian Peninsula and who had to leave their homeland after the expulsion of the Moors due to the Alhambra Edict of 1492. When the Spaniards arrived in Tripoli in 1510, 800 Jewish families fled the city. Some of them strengthened the troglodyte Jewish communities in the Nafusa Mountains near Gharyan . Many returned after the Turks , who appeared in Cyrenaica from 1517, conquered Tripoli in 1551.

Among those who left Spain for North Africa were the ancestors of Shimon ibn Lavi. This Sefard reorganized the religious life of the Jews in Libya in the 16th century and is still considered the father of the Libyan tradition in Judaism.

From the 16th to the early 19th century was rife in the western Mediterranean , the piracy of the Barbary States . Jews often acted as mediators when it came to extorting ransom for captured Christians. But you were also involved in the defense of Tripoli in 1705, when the Bey of Tunis, Ibrahim el-Sherif, besieged the city in a punitive action against pirates. The surprising termination of the siege and thus the rescue of the Jews is the reason for their traditional festival of Purim Sherif . Another regional Purim festival, Purim Burghol , commemorates the redemption of the city from the reign of terror of the corsair of the same name.

From 1711 to 1835 Libya was approved by the largely autonomous dynasty of Qaramanli governed. Thereafter, in 1835, the Hohe Pforte took over the administration of Libya directly and repealed all existing discriminatory regulations for Jews. The Romanian Israel Joseph Benjamin, who traveled to Libya in the middle of the 19th century, reported on almost 1,000 Jewish families with eight synagogues in Tripoli, 400 families with two synagogues in Benghazi, and eight other small communities - some in troglodytes. The total of 2200 families lived from trade, peddling, handicrafts (especially weaving and locksmithing) and agriculture. Despite their legal rights, they suffered from the intolerance of Muslims.

Soon after the unification of Italy, this young state sought influence in Libya. An Italian school was opened in Tripoli as early as 1876, and one year later it also accepted girls. The opening of a school of the Alliance Israélite Universelle (AIU) in 1895 led to a split in the Jewish community because of its modern occidental orientation - it also took in girls.

Italian rule

The colonial conquest of Libya by Italy began in 1911 and initially concentrated on Tripolitania. The Fessan could not be fully brought under control until 1924 and the Cyrenaica only in 1932. The number of Jewish citizens grew and, according to a record of 1931, amounted to 21,000 people in Tripolitania, which corresponded to about four percent of the population. 15,000 of them lived in Tripoli. 3,000 Jews were counted in Cyrenaica, over 2,000 of them in Benghazi. The chief rabbi in Tripoli and many rabbis came from Italy, as did many of the believers who often immigrated from Livorno .

The Jews of Libya enjoyed a certain esteem by the Italian colonial power during the first 25 years and experienced a period of prosperity and progress until, in the 1930s, Italian fascism and Italy's alliance with Nazi Germany led to renewed discrimination. However, from 1939 to 1940, the laws of the motherland were not immediately applied to the Jews in Libya because they often played an important role in building the colony. After the German Afrikakorps marched in in 1941 to support the Italian troops against the British, many Jews in Libya were subjected to forced labor near the front by the Axis powers, deported or interned. After changing fronts twice in Benghazi, almost the entire Jewish population was deported to the Nafusa Mountains because of sympathy with the enemy. In the Giado concentration camp , almost a quarter of the 2,600 inmates died of hunger and typhus within 14 months before the survivors were liberated by the British 8th Army in January 1943 .

Kingdom and mass exodus

The defeat of the German and Italian troops was followed by the rule of a British (Tripolitania and Kyrenaica) and French ( Fezzan ) trustee administration on behalf of the United Nations from 1943 to 1951 . It was through the 1951 Kingdom of Libya with the ruler Idris I. replaced. The British could achieve little in 1945 and 1948 when the rapidly deteriorating relations between Arabs and Jews led to pogroms as a result of Arab nationalism and Zionism . The Tripoli pogrom in 1945 began on December 4, 1945 with anti-Jewish violence in the capital, which also spread to other cities. A total of 135 Jews were killed immediately, 300 wounded - some fatally. The Jews then set up a self- defense organization that was able to defend their old quarters in Tripoli when another attack on Jews broke out after the state of Israel was declared on June 12, 1948. There were 14 deaths on the Jewish side. The riots in Benghazi on June 16 left another victim.

Since their position in the country had become hopeless, between 1949 and 1952 90% of the approximately 36,000 Libyan Jews left the country in a mass exodus. Most of them went to Israel, but some also moved to Rome and other Italian cities. In order to protect the remaining Jews from popular anger during the Six Day War (June 5 to June 10, 1967), the Libyan government decided to put them in a camp outside Tripoli or in a barracks in Benghazi. Nevertheless, there were several deaths and numerous arson and synagogues, shops and houses were looted - also in the new Jewish quarters. Italy in particular helped evacuate the refugees.

Gaddafi's rule

On September 1, 1969, Muammar al-Gaddafi overthrew King Idris I , who was abroad, in a bloodless coup . Around 100 Jews remained in the country at that time. He tightened the rules regarding the whereabouts of Jews in the country and the nationalization of the property of emigrated or absent Jews. Synagogues were converted into mosques or closed. In Tripoli alone there were 62 synagogues before the expulsion of the Jews. The Sla-El-Kebira Synagogue , built in 1628, became a mosque, the building of the former Dar-E-Serousi Synagogue and Hebrew School was renovated in 1994 and used as the city archive, and the Dar-Bishi Synagogue , which was once opened the Italian King Viktor Emanuel III. had participated, was locked and left to decay.

When 81-year-old Rina Debash moved to Rome to live with her nephew David Gerbi on October 10, 2003 , Jewish life in Libya was completely extinct - unlike in any other Arab country. But the culture and customs of the Libyan Jews lived on and enriched the refugees' new home in many ways. Around 200,000 people in Israel and Italy, but also in Great Britain, the USA and other countries are now considered to be descendants of Libyan Jews. Local groups and, above all, the World Organization of Libyan Jews (WOLJ) try to safeguard their interests and keep memories of their old homeland alive. The museum in Or Jehuda and a special Libya department of the Jewish Museum in Rome serve this purpose .

Civil war

When the civil war broke out in Libya during the Arab Spring in 2011 , which ended with the victory of the rebels and the death of Gaddafi, anti-Semitism was also to be found among the revolutionaries. There had always been more or less serious rumors about Gaddafi's origins that he had Jewish ancestors. Graffiti by the insurgents, who insulted him as a Jew and a henchman of Israel, appeared frequently, especially on public buildings. The expert on Libyan Judaism, Maurice Roumani , said after the end of the Gaddafi regime in an interview with Manfred Gerstenfeld from the Jerusalem Center of Public Affairs: “Libyan Jews almost unanimously welcomed the fall of Muammar Gaddafi; they believed he deserved his fate. Gaddafi was notorious for being anti-Israel. "

The World Organization of Libyan Jews (WOLJ) tried early on to contact the National Transitional Council of the insurrectionary movement. David Gerbi, an Italian analytical psychologist who fled to Italy with his parents from Tripoli at the age of twelve, first visited Benghazi in 2011 as a WOLJ delegate. He was given a particularly warm welcome in the fighting area of the Berbers, a minority discriminated against in Gaddafi's Libya. But when he tore down the wall blocking the entrance to the Dar Bishi Synagogue in a media-effective action in Tripoli and announced that he wanted to rebuild the synagogue, he was threatened by a militia and had to flee. His invitation to a congress of the Berbers (International Forum of the Constitutional Rights of the Amazigh of Libya) on the occasion of their New Year celebrations on January 12, 2013 in Tripoli was withdrawn at the last minute on the grounds that his visit was "premature".

After Gerbi's attempt to open the Dar Bishi Synagogue, M. Roumani said of the National Transitional Council (TNC): “A Jew who comes to restore Jewish heritage in a country undergoing a revolution is the last thing the TNC wanted to have on the neck. ”After a popular election, the temporary TNC was replaced on August 8, 2012 by the Libyan General People's Congress . But in view of the continuing unstable situation in the country, compensation for expropriated private and collective property of the refugees, the restoration of synagogues and cemeteries and the possibility of traveling to or returning to Libya in search of one's own roots are still not foreseeable.

literature

- M. Rachmuth: The Jews in North Africa up to the invasion of the Arabs. Monthly for the history and science of Judaism 14, Koebner, Breslau 1906.

- Eli Barnavi: Universal History of the Jews. dtv, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-423-34087-8 .

- Haim Hillel Ben-Sasson, (Ed.): History of the Jewish people - from the beginnings to the present. Translation by Siegfried Schmitz, Beck, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-406-55918-1 .

- Shimon Applebaum : Jews and Greeks in Ancient Cyrenaica. Brill, Leiden 1979, ISBN 90-04-05970-9 .

- M. Roumani: The Jews of Libya: Coexistence, Persecution, Resettlement. Sussex Academic Press, USA 2008, ISBN 978-1-84519-137-5 .

- R. Simon: Changes within Tradition among Jewish Women in Libya. University of Washington Press, Washington 1992, ISBN 0-295-97167-3 .

- André Chouraqui: Histoire des juifs en Afrique du Nord, Tome 1. Roucher, Monaco 1998, ISBN 2-268-03105-3 .

- Joachim Wilhelm Hirschberg et al: A History of the Jews in North Africa. 2nd Edition. Brill, Leiden 1981, ISBN 90-04-06295-5 .

Web links

- M. Roumani: The Final Exodus of the Libyan Jews in 1967. In: Jewish Political Studies Review. 19, pp. 3–4 (Fall 2007)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Applebaum: Jews and Greeks in Ancient Cyrenaica. 1979, p. 130. (Inscription of the seal ring: from Avadyu, son of Yashav - לעבדיו בן ישב)

- ↑ EJ Schnabel: Early Christian Mission. Brockhaus, Wuppertal 2002, ISBN 3-417-29475-4 , pp. 846/847.

- ^ B. Niese, Ed .: Flavius Josephus, Contra Apionem II: 44. In: http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=urn:cts:greekLit:tlg0526.tlg003.perseus-grc1:2.44 . Gregory R. Crane, accessed April 30, 2018 (gr).

- ↑ Flavius Josephus: Antiquitates Judaicae. XIV 7.2, (French, Philippe Remacle)

- ↑ M. Rachmuth: The Jews in North Africa until the invasion of the Arabs. 1906, p. 26.

- ↑ Flavius Josephus: Antiquitates Judaicae. XVI 6.1–2, (Greek and French, Philippe Remacle)

- ↑ Flavius Josephus: History of the Judean War. Reclam, Leipzig 1985, VII 11.1-3, p. 505.

- ^ Cassius Dio: Roman History. Book 68, 32.1-32.3

- ^ Berenike inscription (Greek): D. Emil Schürer: History of the Jewish people in the age of Jesus Christ. Hinrichs, Leipzig 1886, Vol. II p. 515/516 and Vol. III p. 42.

- ^ Berenike inscription (French translation): D. Cazès: Essai sur l'histoire des Israélites de Tunisie. Armand Durlacher, Paris 1888, Appendice I, pp. 193/194

- ↑ 2. Makk. 2:23

- ↑ 1. Makk. 15: 16-24

- ↑ See, for example, Mt 27:32

- ↑ Acts 6: 9

- ↑ M. Rachmuth: The Jews in North Africa until the invasion of the Arabs. 1906, p. 22.

- ↑ A. Chouraqui: Histoire des juifs en Afrique du Nord. 1998, p. 49.

- ↑ E. Schnabel: Early Christian Mission. 2002, pp. 348/349.

- ↑ Le Bohec: Inscriptions juives et judaisantes dans l'Afrique romaine. In: Antiquités Africaines. 17, CNRS, Paris 1981, pp. 165-207 and 209-229.

- ^ Karen B. Stern: Keeping the Dead in their Place: Mortuary Practices and Jewish Cultural Identity in Roman North Africa. In: Erich S. Gruen (Ed.): Cultural Identity in the Ancient Mediterraneum. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles 2011, ISBN 978-0-89236-969-0 , pp. 307-334.

- ↑ Ibn Khaldoun: Histoire des Berbères et des dynasties musulmanes de l'Afrique septentrionale. Translation by William McGuckin de Slane . Editor: Paul Geuthner, Paris 1978, Vol. 1, pp. 208-209.

- ↑ A. Chouraqui: Histoire des juifs en Afrique du Nord. 1998, pp. 49-50.

- ↑ A. Chouraqui: Histoire des juifs en Afrique du Nord. 1998, pp. 263-264.

- ^ Tertullian, Adversus Judaeos. (German)

- ↑ Codex Theodosianus III 7.2 and XIV 8.6 (Latin)

- ↑ M. Rachmuth: The Jews in North Africa until the invasion of the Arabs. 1906, p. 44.

- ↑ Codex Iustinianus CJ.1.11.10 ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (Latin)

- ↑ Justiniani Novella 37

- ↑ Prokopius, de aedificiis VI 2.21–2.23 History of Boreium (English).

- ↑ E. Barnavi: Universal History of the Jews. 2004, p. 81.

- ↑ E. Barnavi: Universal History of the Jews. 2004, p. 83.

- ↑ a b A. Chouraqui: Histoire des juifs en Afrique du Nord. 1998, p. 257.

- ↑ Moshe Gil , David Strassler: Jews in Islamic Countries in the Middle Ages. Brill, Leiden 2004, pp. 550, 557.

- ↑ A. Chouraqui: Histoire des juifs en Afrique du Nord. 1998, p. 256.

- ^ Goldstein-Goren International Center of Jewish Thought, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Israel

- ↑ A. Chouraqui: Histoire des juifs en Afrique du Nord. 1998, p. 262.

- ^ R. Simon: Changes within Tradition among Jewish Women in Libya. 1992, pp. 111-127.

- ↑ E. Barnavi: Universal History of the Jews. 2004, p. 188.

- ^ A b H. Hirschberg et al.: A History of the Jews in North Africa. 1981, p. 185.

- ^ H. Hirschberg et al.: A History of the Jews in North Africa. 1981, p. 186.

- ^ M. Roumani: The Final Exodus of the Libyan Jews in 1967. (PDF; 241 kB) In: Jewish Political Studies Review. 19: 3-4 (Fall 2007), Beginning of the End section .

- ↑ R. Luzon: In Libya now. ( Memento from December 11, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) In: Jewish Renaissance. April 2005, p. 21.

- ^ M. Roumani: The Final Exodus of the Libyan Jews in 1967. (PDF; 241 kB) In: Jewish Political Studies Review. 19: 3-4 (Fall 2007), Section 1969: Qadhafi's Coup .

- ^ World Organization of Libyan Jews

- ↑ Libyan Museum in Or Yehuda (flickr)

- ↑ Museo Ebraico di Roma , room 7

- ↑ The Mystery Behind Gadhafi's Birthplace: Some Say He's Jewish. AOL News, March 31, 2011.

- ↑ Come and be an Israeli! In: The Economist , September 10, 2011.

- ^ Libia, l'antisemitismo (senza ebrei) dei rivoluzionari. In: Corriere della Sera , April 9, 2011.

- ↑ a b Manfred Gerstenfeld : Libyan Jews observe life after Gaddafi , Jerusalem Center of Public Affairs, February 15, 2012.

- ^ World Organization of Libyan Jews offers support to Leader of Transitional Council in Benghazi . ( Memento of April 27, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) In: La Stampa , July 25, 2011.

- ↑ Amazigh rebels embrace representative of Libyan Jews. In: Jerusalem Post , September 4, 2011.

- ^ Libyan Jew returns home after 44-year exile , Reuters , October 1, 2011.

- ^ Libyan Jewish leader barred from Tripoli conference . In: Jerusalem Post , January 20, 2013.