History of the Jews in Slovakia

The History of the Jews in Slovakia is in line for a period of nearly a thousand years of history of Jews in Hungary , as Slovakia until 1918 to Kingdom of Hungary was one and mostly Upper Hungary or "Oberland" ( Slovak Horná Zem , Hungarian Felvidék or Felföld ). The Jews from this region were accordingly called "Oberlanders". After the establishment of Czechoslovakia (October 28, 1918), Czech and Slovak Jews were given full legal equality. From the summer of 1940, the Jews in Slovakia were increasingly persecuted, around 70,000 of them fell victim to the Holocaust .

Kingdom of Hungary until 1918

Sporadic references to the existence of Jews in present-day Slovakia have existed since the middle of the 13th century. In the Middle Ages and afterwards, some flourishing Jewish communities ( communitates Judaeorum in Latin ) are noted in contemporary historical documents and in rabbinical literature . The best known are Bratislava , Senica , Trnava , Nitra , Pezinok and Trencin . The Bratislava community alone counted 800 Jews in the 14th century, who formed an autonomous political body that was headed by a community leader. Some Jews from this region were engaged in agriculture and wine-growing, but most of them in trade and money lending. After a ritual murder charge in 1494, Jews in Trnava were sentenced to death at the stake. The same charge was brought against the Jews of Pezinok in 1529 because the lord of the city owed them. Here 30 of the accused were burned at the stake.

After the Battle of Mohács (1526) , the Jews were expelled from the cities and settled in the surrounding villages. It was not until the 17th and early 18th centuries that larger numbers of Jews were found on the country estates of the Hungarian nobles such as B. the families Pálffy , Esterházy , Pongrácz etc., which placed them under their protection and granted them some freedoms. At that time there was a constant conflict with the townspeople, especially with the representatives of the guilds , the majority of whom were of German origin, who knew how to prevent Jewish competitors from entering the towns and doing business. The tolerance patents that were granted in the course of the Josephine reforms improved the situation somewhat, but it was not until 1840 that Jews were granted residency rights in the cities again. According to the 1785 census, the Bratislava municipality was the largest in Hungary at that time, followed in second place by Nové Mesto nad Váhom .

In the 18th century there was a wave of immigration from Moravian Jews who sought refuge from the discriminatory family laws introduced by Charles VI in 1726 . were introduced, whereby the number of Jews in Bohemia, Moravia and Silesia, their eligibility for marriage and the right of residence were subject to numerous restrictions. The new immigrants founded Jewish training centers in Pressburg, Huncovce and Vrbové . The Pressburg yeshiva , which had existed since around 1700, took on a leading role in the 19th century , particularly through the influence of the Orthodox rabbi Moses Sofer .

Chatam Sofer (1762–1839) was a 19th century rabbi who was known beyond the borders of the country and was chief rabbi in Bratislava for 33 years . In 1942 the Jewish community succeeded in preserving Chatam Sofer's grave and a number of other rabbis. An elaborate concrete sarcophagus was built around the graves. Fifty years later, on the initiative of the "International Committee of Genoai", a New York association, the reconstruction began.

The rise of Slovak nationalism at the end of the 19th century coincided with the beginning of Zionism . Of the 13 local Zionist groups that were established in what was then Hungary after the first Zionist Congress in 1897, seven were in today's Slovakia (Bratislava, Nitra, Presov , Košice , Kezmarok , Dolný Kubín and Banská Bystrica ). In addition, the first Hungarian Zionist congress took place in Bratislava in 1903, and the first Misrachi congress in 1904 . In the First World War, Zionist activities came to a standstill and were only resumed after the establishment of Czechoslovakia.

Czechoslovakia until 1939

After the collapse of the Habsburg monarchy , Czechoslovakia was founded in 1918 . Slovakia did not have a statute of autonomy in it, it did not receive this until 1938. Both today's states, i.e. the Czech Republic and Slovakia, have a common history over historical stretches.

During the time of the Czechoslovak Republic (ČSR) the Jews could feel as free citizens. But in 1938 the partial Slovak autonomy promoted by Germany brought an end to normal civilized life for the Jewish Slovaks and foreigners of the Jewish faith in Slovakia.

A few months after the Munich Agreement of 1938, on March 14, 1939, the "remaining Czech Republic " was smashed with the independence of the (First) Slovak Republic , the Carpathian Ukraine , and on March 15, Bohemia was occupied by the German armed forces with the establishment of the " Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia ". In the further course of the occupation, almost the entire Jewish population of the Protectorate was interned in the Theresienstadt ghetto and from there mostly deported to the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp . Of around 82,000 Jews deported from the Protectorate, only around 11,200 survived the Holocaust .

At the 1930 census, there were 136,737 Jews living in Slovakia (4.11% of the total population). Jewish Slovaks lived in 1435 of the approx. 2700 communities and cities. According to Rothkirchen, there were 167 Israelite religious communities in Slovakia . The largest Jewish communities were Bratislava (up to 15,000 people), Nitra (4358), Prešov (4308), Michalovce (3955), Žilina (2917), Topoľčany (2459), Trnava (2445), Bardejov (2441), Humenné (2172 ) and Trenčín (1619). After the First Vienna Arbitration on November 2, 1938 and the occupation of parts of southern Slovakia by Hungarian troops, around 89,000 Jewish people remained in Slovakia.

The ideological basis for the implementation of anti-Jewish measures by Hlinka's Slovak People's Party and its supporters was the thesis that the Jews were "arch enemies of the Slovak state and people".

On September 19, 1941, the Reich Minister of the Interior decreed that all Jews in the sphere of influence of National Socialism would in future have to wear a Star of David clearly visible on their outer clothing. Similar edicts had been issued two years earlier in the Polish General Government. From October 1941 Heinrich Himmler forbade all Jews to leave the German Reich. They were now systematically recorded by the police (registration offices, separate ID cards) and, as the next step, isolated from non-Jews in separate apartments ( Jewish houses ). After various other attempts, the systematic mass deportation of German Jews to the East began on October 15, 1941 . Similar measures were soon taken in Slovakia.

Persecution and deportations

Eduard Nižňanský describes the measures of persecution, robbery and murders in five phases that can be represented separately, but with some smooth transitions. Essential for these phases is the more or less direct access by German rulers to the police of the First Republic under Jozef Tiso and the military occupation of the country after September 1944.

1. From October 6, 1938 to March 14, 1939 - the preparatory stage: as described by Nižňanský. During the period of autonomy, a predominantly ideological dispute about the "solution of the Jewish question" took place within Slovakia. On the one hand the conservative-moderate line around Tiso and on the other hand the radical-fascist line around Vojtech Tuka , who later became Prime Minister, and Alexander Mach , the head of the Hlinka Guard . The radicals wanted to solve the Jewish question as quickly as possible, following the model of expatriation in Germany. The so-called Sidor Committee worked out anti-Jewish laws (government ordinances) for this purpose. The first wave of deportations came in November 1938. It is interpreted as a reaction to the loss of territory in Slovakia through the First Vienna Arbitration Award to Hungary . Jews are responsible for the loss of territory, then they should pay for it. In November 1938, the pro forma autonomous government deported around 7,500 Jews from Slovakia to the area to be ceded to Hungary.

2. Between March 14, 1939 and August 1940, Jewish citizens lost their rights: In April 1939, the first denominational definition of Slovak Jews was adopted and laws were enacted that excluded these Jews from public and economic life . Then, according to the "Law 113/1940", companies were Aryanized .

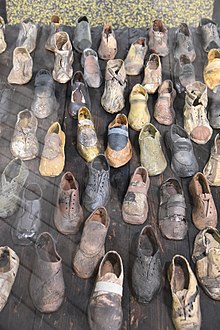

3. From September 1940 to October 1942 - presence of the German adviser for Jewish questions : Dieter Wisliceny , SS-Hauptsturmführer and confidant of Eichmann ; He pursued the plan to solve the social problem created by the expropriation of the 89,000 Jewish citizens through the "emigration" of the dispossessed or their exile. Behind it was nothing other than deportation to the extermination camps . In September 1940 the Slovak parliament gave the government the power to resolve the Jewish question within a year. During the following 12 months, over 300 orders and pronouncements were issued through which the Jewish residents were systematically deprived of their economic and civil rights. For this purpose, a central economic office (Ústredný hospodársky úrad) was created for the aryanizations. All Jews had to join a compulsory corporation (Ústredňa Židov). Efforts to set up Jewish ghettos and large labor camps were quickly stopped. The next stage of the deportations is based on an agreement of December 2, 1941 between Prime Minister Tuka and the German envoy and SA- Obergruppenführer HE Ludin on deportations (this resulted in a deportation law in the event of loss of citizenship). The first transport of the so-called Aktion David took place from Poprad on March 25, 1942. Even before May 15, 1942, when the constitutional law on the evacuation of Jews was discussed in parliament, 28 transports with around 28,000 people left Slovakia. The Slovak side committed itself to the German Reich to pay 500 RM for every deported Jew and to hand over his property to the Reich. By October 20, 1942, 29 more transports left the territory of Slovakia. In 1942 a total of 57,628 Jews were deported from Slovakia. In 2000 the “Central Association of Jews in Slovakia Germany” sued for repayment of this amount and compensation totaling 78 million euros. The lawsuit was finally dismissed in January 2003 on the grounds that the central association could not be regarded as the legal successor to the murdered Jews.

4. From November 1942 to August 1944 there was a so-called "rest period": In Slovakia there were still about 19,000 Jews, of which about 4000 were in the Nováky , Sereď , Vyhne or so-called VI labor camps . Battalion. Individuals survived due to various exemptions for Jews (presidential exemptions, exemptions from various ministries).

5. From September 1944 to the end of the war: In the period of the Slovak National Uprising from August 29 to the suppression on October 27, 1944, the anti-Jewish laws were suspended by the Slovak side. After the occupation of all of Slovakia by German units in September 1944, the last stage of the deportations began. Previous exceptions were overridden by the occupiers and the transports to the extermination camps, which affected another 13,000 Jews, were resumed. About 1000 people were murdered directly in Slovakia. Thanks to the help of individual Slovaks, around 10,000 Jews were rescued in the country by fleeing or illegally hiding in this phase of the deportations.

post war period

A large part of the history of the Jews during the period of persecution and deportation has not yet been processed. The Holocaust was a taboo subject in Slovakia for almost 70 years. There was no mention of their own involvement in the Holocaust, including that of the Catholic Church. The Sered labor camp was a barracks before the war and was reopened as such after the war, where generations of soldiers received their basic training. A memorial plaque had been in place since 1998, but the Jews were not mentioned. Only in 2016 the first Holocaust memorial in Slovakia was opened in part of the barracks area. Building No. 1 is about Slovakia's participation in the Holocaust, Building No. 4 is dedicated to the murdered Jews. The restoration of the other barracks is awaiting funding.

After the war, the property was not returned to the Jewish community. Those who were persecuted during World War II received compensation from the Jewish Claims Conference , but not from the state.

In the mid-1990s, a five-meter-high bronze statue by the Slovak artist Milan Lukač was erected on the site of the old synagogue in Bratislava in memory of the 70,000 deported and murdered Slovak Jews . In 2001, the 9th of September was set by law as “Remembrance Day for the Victims of the Holocaust and Racist Violence”. There is only a very small Jewish community left in Slovakia. After the horrors of the war, the community continued to shrink during the decades of the real socialist regime. Around 800 Jews live in the capital, Bratislava (as many as in the 14th century), and there are other Jewish communities in the country's other major cities. One of the main problems is aging. A Jewish museum was established in Bratislava in 2011, the collection of which reflects the country's Jewish heritage from the first written records in 1270 to the ban on all activities in 1940.

See also

literature

- Encyclopaedia Judaica , Articles: Slovakia (Volume 14) and Czechoslovakia (Volume 5). Thomson / Gale, Detroit 2007, ISBN 0-02-865928-7 (English).

- Wolfgang Benz , Hermann Graml , Hermann Weiß : Encyclopedia of National Socialism . 1997; 5th edition, Klett-Cotta and Deutscher Taschenbuch-Verlag (dtv), Stuttgart / Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-423-34408-1 .

- Wolfgang Benz, Barbara Distel (ed.): The place of terror . History of the National Socialist Concentration Camps. Volume 9: Labor education camps, ghettos, youth protection camps, police detention camps, special camps, gypsy camps, forced labor camps. CH Beck, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-406-57238-8 .

- Bernward Dörner : Justice and the murder of Jews. Death sentences against Jewish workers in Poland and Czechoslovakia 1942–1944. In: Norbert Frei (Ed.): Exploitation, destruction, public. New studies on National Socialist camp policy (= representations and sources on the history of Auschwitz. Volume 4). De Gruyter Saur, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-598-24033-3 , pp. 249-263.

- Aron Grünhut: Time of the catastrophe of Slovak Jewry. The rise and fall of the Jews of Pressburg. Self-published by A. Grünhut, Tel-Aviv 1972, OCLC 923116526 .

- Jörg Konrad Hoensch (Ed.): Jewish emancipation - anti-Semitism - persecution in Germany, Austria-Hungary, the Bohemian countries and in Slovakia (= publications of the German-Czech and German-Slovak historians' commission. Volume 6; publications of the Institute for Culture and History of Germans in Eastern Europe. Volume 13). Klartext, Essen 1999, ISBN 3-88474-732-0 .

- Jörg Konrad Hoensch: History of the Czechoslovak Republic. 1918-1988. 3rd, verb. and exp. Edition. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart a. a. 1992, ISBN 3-17-011725-4 .

- Yeshayahu A. Jelinek : The “Final Solution” - The Slovak Version. In: Michael R. Marrus : The Nazi Holocaust: Historical articles of the destruction of European Jews. 4. The “Final Solution” outside Germany. Vol. 2. Meckler, Westport 1989, ISBN 0-88736-258-3 , pp. 462-472.

- Livia Rothkirchen: The Slovak Enigma: A Reassessment of the Halt to the Deportations. In: Michael R. Marrus: The Nazi Holocaust: Historical articles of the destruction of European Jews. 4. The “Final Solution” outside Germany. Vol. 2. Meckler, Westport 1989, ISBN 0-88736-258-3 , pp. 473-483.

- Rebekah Klein-Pejšová: Among the Nationalities: Jewish Refugees, Jewish Nationality, and Czechoslovak State Building, 1914–38. Dissertation at Columbia University, 2007, ISBN 978-0-549-05542-6 (English).

- Jiří Kosta (Ed.): Czech and Slovak Jews in the Resistance 1938–1945 (= series of publications by the Fritz Bauer Institute . Vol. 22). Translated from the Czech by Marcela Euler. Metropol, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-940938-15-2 .

- Ladislav Lipscher: The Jews in the Slovak State 1939–1945 . Munich: Oldenbourg, 1979, ISBN 3-486-48661-6

- Eduard Nižňanský : The deportations of the Jews in the time of the autonomous country Slovakia in November 1938. In: Yearbook for anti-Semitism research. 7, 1998, pp. 20-45 ( niznanskyedo.host.sk ( memento of March 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive )).

- Eduard Nižňanský: Nacizmus, holokaust, slovenský štát. Kalligram, Bratislava 2010, ISBN 978-80-8101-396-6 (Slovak).

Web links

- Eduard Nižňanský: The Holocaust in Slovakia (RTF file; 39 kB). See also Eduard Nižňanský at WorldCat

Individual evidence

- ↑ Art. 106 constitutional document of the Czechoslovak Republic of February 29, 1920 (Collection of Laws No. 121/1920; original version). In: verfassungen.net, accessed on September 10, 2017.

- ↑ a b c Sylvia Perfler: Anti-Semitism in Slovakia. In: david.juden.at. David, accessed March 7, 2017.

- ↑ See Wolf Oschlies : Aktion David - 65 years ago 60,000 Jews were deported from Slovakia. In: The future needs memories . April 12, 2007, Retrieved October 24, 2018 (article updated August 20, 2018).

- ↑ Zuzana Vilikovská: First Slovak Holocaust museum opens. In: The Slovak Spectator . February 9, 2016, accessed March 7, 2017.

- ^ Sereď Holocaust Museum. In: snm.sk. Slovak National Museum, accessed March 7, 2017.

- ^ Jewish Community Museum. In: slovak-jewish-heritage.org. Slovak Jewish Heritage Center, accessed March 8, 2017.