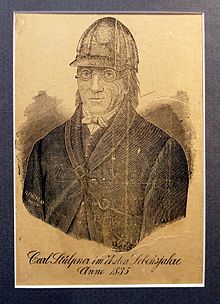

Karl Stülpner

Karl Stülpner , actually Carl Heinrich Stilpner , (born September 30, 1762 in Scharfenstein , † September 24, 1841 ibid) was an Erzgebirge soldier , poacher , smuggler , manufacturer and bon vivant .

Contemporary biographies embellished with literature and subsequently even more free depictions of his life story in narratives, novels, folk theater plays and finally film adaptations have led to extensive legends and contributed to the fact that Stülpner is still regarded as a folk hero in his home region and occasionally referred to as the " Saxon Robin Hood " becomes.

Historical background

Saxony

During the Seven Years' War (1756–1763), the Electorate of Saxony suffered considerable damage and ended up being heavily in debt. In the course of the rétablissement, Elector Friedrich Christian († 1763) and Prince Xaver (regent from 1763 to 1768) introduced a series of reforms. a. promoted the beginning industrialization . A reorganization of forest and game management, which was also planned, was not implemented. Little changed in the situation of the rural population either. Economic emergencies and other grievances led to the peasant uprising of 1790 , which was put down with military force. Between 1805 and 1814, the Napoleonic Wars again caused material stress and political uncertainty.

Ore Mountains

In the wake of centuries of mining, the Erzgebirge was relatively densely populated and was used for agricultural purposes to the limit of what was possible at the time. The overhang of the wild stocks operated by the landlords and sovereigns additionally reduced the already modest and uncertain yields of agriculture in the harsh climate. After bad harvests and price increases in 1771 and 1772, there was a famine that claimed several thousand victims.

Scharfenstein manor

The owners of the Scharfenstein manor and landlords of the surrounding towns were members of the von Einsiedel family around 1800 . The management of the property was entrusted to a tenant and the administration of the patrimonial court to a court administrator based in Thum . A permanent gendarmerie or police were not yet available to this ruling and judicial structure. The dispute with poachers was largely left to the hunting and forest workers on site.

Biographical sources

Only a few details from Karl Stülpner's curriculum vitae can be documented. A large part of the stories passed down is based solely on the literary rather than documentary works of his contemporaries Friedrich von Sydow and Carl Heinrich Wilhelm Schönberg . Systematic research in official documents was only undertaken from the second half of the 20th century, in particular by the teacher and local researcher Johannes Pietzonka . In the process, many differences between the traditional tradition and the file situation came to light. Most of the adventures and anecdotes that shaped Stülpner's character image and his long-lasting popularity are anyway such that they cannot be examined.

Friedrich von Sydow spent his childhood in Thum , joined the infantry regiment “Prince Maximilian” in 1794 at the age of thirteen, in which Stülpner also served from 1779–1785 and 1800–1807, and was initially stationed like him in the Ore Mountains. After an eventful military career, v. Sydow in March 1812 with the rank of premier lieutenant as commander in Freiberg and published there in June and July of the same year under the author's abbreviation F. v. See in numbers 23 to 29 of the weekly "Freyberger non-profit news" a sequel with the title Carl Stülpner, a notorious poacher in the Saxon Ore Mountains . However, he did not explain when and how the events described therein came to his knowledge.

Twenty years later, v. Sydow, now living in retirement in Sondershausen , the material again and expanded under the title Der infamous Wildschütz des Erzgebirge Carl Stülpner - A biographical painting, laid out true to the truth and painted with romantic colors . In this work the decoration with fictional elements is obvious.

Another three years later, Carl Stülpner's strange life and adventure appeared as a game shooter in the Saxon high mountains, as well as the fate he suffered during his 25 years of military service under different war periods and nations. Faithfully communicated by himself to the truth, and edited by Carl Heinrich Wilh. Schoenberg . When, where and in what way Schönberg was in contact with Stülpner is not yet known. To v. Sydow's Stülpner biography from 1832, Schönberg remarks that it was published [...] neither with knowledge nor with Stülpner's permission [...] and that it contains exaggerated and incorrect information. As far as the content is identical, Schönberg's text is often almost literally similar to that of its predecessor.

The history of Karl Stülpner, the bold game shooter of the Saxon-Bohemian Ore Mountains, portrayed in poetic guise and, according to Stülpner's own tradition, communicated by Paul Haar in 1888 is an adaptation of Schoenberg's biography. In contrast to other literary post-exploiters, Haar himself carried out research on site and presented some previously unpublished episodes and data in the form of footnotes. He mentions the Scharfensteiner mayor Wilhelm Gottschalk, whose housemate Stülpner was at times, as an informant.

The synopsis of these sources gives the following

Compiled biography

1762 to 1779, childhood and adolescence

Carl Heinrich Stilpner was born on September 30, 1762 (according to Schönberg on September 20, 1761) as the last of eight children of Johann Christoph Stilpner. Since 1745 the family had owned a cottage with a garden and a piece of high forest in Scharfenstein, Karl's father earned his living mainly as a miller and shoemaker. Karl's mother Marie Sophie was a daughter of the cottage trader and rifleman Melchior Schubarth (according to Schönberg: […] the lordly forester in Scharfenstein, a certain Mälcher […] ).

Schönberg: After he was able to attend school, he was [...] sent to the school in Großolbersdorf half an hour away.

Pietzonka: The local history researcher R. Höfer knows from old school files that Karl went to the boys' school with Rector Johann Gotthelf Gläser from 1771 to 1774 [...].

Schönberg: When Karl [...] reached the age of eight, his father [...] died of complications from a breast infection.

Pietzonka: There is no corresponding note in the responsible register of deaths in Großolbersdorf, but there is an entry gap from 1771 to 1774.

In 1772 the Scharfenstein court repertory recorded a report on the meat and grain dove (deube = theft) committed by Marien Sophien Stilpnerin, her son and son-in-law Gottfried Mehnern at the local castle . This is just a registration note that does not reveal whether there has been any subsequent indictment or conviction. The report itself is lost, so the name of the “little son” remains anonymous. Karl was around ten at that time, the other two sons of the Stilpnerin around 16 and 21 years old, respectively. Schönberg and von Sydow do not mention the incident.

Schönberg: When he entered his 10th year, a relative, the forester Müller from Ehrenfriedersdorf , took him to live with him [...]. There, Karl was introduced to the hunter's trade.

Pietzonka: The existence of a Forstadjunkt CC Müller in Ehrenfriedersdorf can be proven, but the relationship has not yet been established.

Schönberg: Carl stayed here in Ehrenfriedersdorf until he was 12 years old, when, at the urgent request of his mother, he returned to her in Scharfenstein.

Haar: In 1774 the Stilpner's house was foreclosed on account of accumulated debts. Marie Sophie Stilpner retained the right to a free apartment in the house until her death.

Schönberg: Karl took odd jobs to help make a living. Even after he had been confirmed by the worthy Pastor Portius after completing the 14th year in Großolbersdorf, he still stayed in his mother's home and tried all sorts of handicrafts for himself and his mother [...] to satisfy the most essential needs of life. Because of his hunting skills, he was also used for stately hunts.

According to Schönberg, Karl Stülpner was called up for military service for the first time when he was less than 16 years old. He had served as a train soldier for two years in the War of the Bavarian Succession (1778/79) and was finally only released at the energetic instigation of his mother and returned to Scharfenstein. Von Sydow does not report anything about this episode. Pietzonka mentions her with a reference to Schönberg, but found no confirming documents herself and suspects only an auxiliary service as a "baggage boy".

Haar: At the age of 18, Stülpner is said to have been caught poaching by a forester and injured in the forehead by a shotgun.

1779 to 1785, military service

Historical team lists show that Carl Heinrich Stilpner got himself 18 groschen in November 1779 for a hand money of 2 talers. H. voluntarily committed itself to an eight-year period of service at the Saxon Infantry Regiment "Prince Maximilian" and in January the regiment in Chemnitz in growth was taken. Von Sydow mentions Stülpner's entry into the military in 1812 without any further details. Only in his novel from 1832 did he add the story that Stülpner had been forcibly recruited, but escaped the recruiting squad and hurried ahead to Chemnitz in order to at least get the cash there by apparently voluntary entry. Schönberg also describes forced recruitment, but without the escape episode.

Karl Sewart points out that Stülpner's entry into Chemnitz was actually unusual, because according to the recruiting districts established at the time, he actually belonged to the catchment area of the Zschopau unit. When Stülpner was transferred to Zschopau in November 1784, this irregularity was eliminated. Schönberg's statement that Stülpner served three years in Zschopau does not match the dating of the transfer note. According to the latter, he was only there for a few weeks. Schönberg explicitly cites the reason for the transfer that Stülpner has been increasingly receiving complaints about poaching. Although Stülpner was officially entrusted with hunting tasks in the areas leased by his superiors as part of his service, he often crossed the area boundaries with the tacit approval of his clients. Also v. Sydow reports illegal hunting activities of Stülpner, but only on his own hand during the home leave in Scharfenstein.

At the end of 1784 it is on record that Stülpner was arrested by the staff for assaulting a hunter . This arrest lasted more than half a year without a conviction. Stülpner was even taken to a maneuver as a prisoner. On the march back, according to the crew list, he deserted on July 3, 1785 in Simselwitz near Döbeln outside arrest .

1785 to 1794, time of hiking or poaching

According to Schönberg, Stülpner only returned shortly after his desertion to Scharfenstein and then went to Bohemia. For the next few years, Schönberg names the following stations (spelling of the place names according to the source):

- 2 years as a house servant in an inn in Grümau near Sebastiansberg

- 3 years as a Forstadjunkt with a Count von Nostitz in Heinrichsgrün

- 10 months as a hunter with a Hungarian count named Wesslini in Debrezyn

- Hike via Vienna to Bohemia, Bavaria, Lower Austria, Tyrol, Innsbruck , Switzerland, Baden, Hesse, Hanover

- Recruited as a dragoon at Osterode, deserted after 1 year and 4 months

- some time back in the Ore Mountains as a poacher

- some time around Baireuth

- 2 years as a district hunter with a Mr. von Reitzenstein on Kunersreuth

- 14 months as a district hunter with a Herr von Plotaw on Zedwitz in the area of Hof

- forcibly recruited by Prussian recruits in Bayreuth

- 2 years as a musketeer in the Prince Heinrich Infantry Regiment in Spandau

- 1792/93 participation in the war of intervention against France

- deserted near Weissenburg in autumn 1793

- Easter 1794 to Scharfenstein and returned to life as a poacher

None of this has yet been proven. In addition, the sum of the periods of time mentioned by Schönberg does not fit into the interval between July 1785 and Easter 1794 by far. Instead, Stülpner led a life as a poacher in the Saxon-Bohemian border area throughout the period in question.

In 1974, Klaus Hoffmann quotes the registration note of an ACTA from the repertory of the Selva Justice Office , which was made obediently at the regional forester, H. Johann Gottlieb Fierigs in Jöhstadt , in the Ober-Amte Preßnitz Reporting by swdm pending on 1788 . Although the file itself is lost and the note in the register does not reveal whether the “arrest” was followed by an indictment and conviction, Hoffmann believes that a longer prison sentence is more likely than extended travel.

1794 to 1800, return to society

The next striking event is a failed attempt by the manorial court authorities to arrest Stülpner in his mother's domicile in Scharfenstein. Not only v. Sydow and Schönberg report on it in detail, but also a participant and eyewitness, the chief forester Pügner from Geyer . Pügner's report to his superior names, among other things, the exact time of the action: the night of October 12th to 13th, 1795. In some points, e.g. B. the listing of Stülpner's hunting utensils confiscated during the house search, v. Sydow and Schönberg agree with Pügner down to the smallest details. In other points, the representations differ considerably, especially with regard to Stülpner's counteraction, the so-called “Siege of Scharfenstein Castle”, which has since been considered his most famous and brazen trick. Incidentally, Pügner's report also contains a reference to Stülpner's partner: Since he was not found in the house as hoped, but was seen in town, the assumption arises that the Stilpner cared for a person in Scharfenstein (i.e. had fun with a girl). He probably stuck with this person.

It should be noted that only the wording of the report by Chief Forester Pügner has survived. The writer Kurt Arnold Findeisen , also the author of a Stülpner novel, quoted him in 1921 in the magazine “Sächsische Heimat”, which he published. The document itself was investigated at the beginning of the 21st century. undetectable.

Around 1795, around 1795, Stülpner is said to have begun to explore the possibility of his pardon and return to normal life. For this purpose, according to v. Sydow addressed the tenant of the Scharfenstein manor, according to Schönberg, besides the tenant named Philipp (Samuel Gottlieb Philipp in Scharfenstein is proven until 1798), the landlord Major von Einsiedel (Alexander Abraham von Einsiedel, d. 1798, can be identified by the rank) . As a result, an unofficial agreement was reached: Stülpner stopped poaching and stayed inconspicuously in Scharfenstein, in return, well-meaning personalities worked towards his pardon. Stülpner was credited with the fact that, apart from poaching, he never committed serious crimes and, on the contrary, even stopped robbers.

In the edition of December 17, 1795, the newspaper " Leipziger Newspapers " published a profile with a personal description of Stülpner and the assurance of 50 thalers as a reward for his capture, as well as for information that led to his arrest. The signatories include a. Julius Friedrich David von Zinsky. On the other hand, Schönberg mentions a Rittmeister von Zinsky as one of Stülpner's patrons, who also provided him with material support on the path to rehabilitation.

On February 26th, 1796, the registry of Großolbersdorf notarized a death-born son Hannen Christianen Wolfin, if he received them in dishonor from Heinrich Stilpner from Scharfenstein […]. with the comment: Stilpner, since he is not allowed to show himself, indicated himself to the local wife Wolfin as the father of this womb [...]. Stülpner's lover Johanne Christiane Wolf, the daughter of the local judge Johann Christian Wolf from Scharfenstein, was eighteen years old at the time, and Stülpner was thirty-three.

On July 11, 1799, the birth of their daughter Johanne Eleonore was registered. Stülpner, in turn, immediately acknowledged paternity.

1800 to 1807, second military service

Clues for Stülpner's return to the military are provided by a crew list of the Prinz Maximilian regiment. In addition to his personal details, under the heading How did he come to this regiment and company? the note: d. 11 September 1800 reported as arrestant . In the category whether he has a capitulation? is noted: No! This means that Stülpner's “capitulation” (ie, the limitation of the period of service) of 8 years agreed in 1779/80 was no longer valid, which corresponded to the regulations for deserters at the time. Otherwise Stülpner was according to v. Sydow was only punished with a four-week arrest for deserting 15 years ago, according to Schönberg he even got away without any punishment. He was also not prosecuted for poaching.

A short time later, when Stülpner had returned to his regiment, Schönberg invented his marriage to Christiane Wolf, soon afterwards a capable boy and later a family that grew with more children. In reality, Stülpner's third child, Christiane Eleonora, became “dishonest” on January 4, 1806. H. Born out of wedlock and died after a few days.

Both biographers certify Stülpner's participation in the campaign against Napoleon in 1806. Schönberg's statement that at this point he had already served for nine years is incompatible with the date of his re-entry. After the troops returned to the garrison, a company list records Stülpner as deserting on vacation in May 1807 . This was done out of disappointment, claim v. Sydow and Schönberg, because they had given him futile hopes of an early dismissal and a job as a forester.

At this point v. Sydow as a biographer, because in his publication in the summer of 1812 he did not yet have anything to report about Stülpner's further fate, and what he wrote about it in his later novel is obviously fictitious.

1807 to 1820, starting a business and family life

Schönberg: After his recent desertion, Stülpner went back to Bohemia, where he leased a tavern near Sebastiansberg on St. Christoph Hammer , and had his family follow him there .

Pietzonka: The Wildschütz is said to have leased a tavern in Zobietitz near Sonnenberg .

Schönberg: After "Generalpardon" d. H. After a general amnesty was issued, the Stülpner family returned to Scharfenstein, and in 1814 Stülpner bought a house in Großolbersdorf .

Pietzonka: It is on record that the Stilpnerin bought a house on July 22nd, 1816 . Their family name suggests that the couple had since married. This is also indicated by the entry in the register of the fourth child: the daughter Christiane Concordia was born “honestly” on November 24, 1816, but died after just a few weeks.

Schönberg: Stülpner stayed in Großolbersdorf for 5 years, and then [...] again emigrated to Bohemia, where he settled in Preßnitz and successfully traded in Pasch. (i.e. illegal smuggling business) Soon afterwards he died there on October 15th. In 1820 his wife suffered the consequences of a difficult confinement […].

Pietzonka: According to the death register, Johanne Christiane Stilpner née Wolf died on May 31, 1820 in Preßnitz. [...] Her husband is Carl Heinrich Stilpner, a thread manufacturer !! (At this point, however, Pietzonka does not provide any details about this trade from Stülpner.)

1820 to 1831, second marriage and return to Saxony

On August 11, 1823, Stülpner married Maria Anna Veronika Wenzora, who was 31 years his junior in Preßnitz. In addition to the birth entry of their son Carl Friedrich, who was born out of wedlock on April 24, 1821, the Preßnitz church book contains the note: XXX der Karel Heinrich Stilpner, Taglöhner u. Inhabitant all here Nro 404 [...] declared himself the father of this child and marked himself in; which was also legitimized as marital by the subsequent marriage. (If the three crosses are supposed to represent Stülpner's handwritten drawings, this indicates that he was not able to write.) Another son named Johann was born on August 20, 1828.

Schoenberg does not mention this relationship with a single word; he writes about the time after 1820 only succinctly: Stülpner remained in Bohemia until 1828, where the great misfortune struck him that he became completely blind due to the starling. In this very sad situation for him he stayed until 1831, when he submitted to the operation in Mittweida with the now deceased city judge Seyfarth, but only regained his eyesight in his left eye. In a footnote to this text passage, Schönberg publishes Stülpner's thanks to a supporter named Preussler, who not only took him very sympathetically in this most unfortunate situation for him, but also made sure that he was operated on, and even more so the cost of the operation was borne by his own means, which amounted to over 25 thalers. amounted to […] . Accordingly, Stülpner moved back to Saxony around 1830. The circumstances of the separation from his second wife are not known. According to Pietzonka, there is evidence that she was still alive in 1855.

1831 to 1841, late years of wandering and the end

In the foreword to his Stülpner biography, published in 1835, Schönberg describes the protagonist as a person [...] who, in his already advanced age, stands here so completely isolated, has no definite and fixed domicile and, with regard to his trembling hand and weakened eyesight, not wealthy is to secure one's meager existence for oneself […] . Where Stülpner was staying during this time and what he lived on is not documented.

At the age of 72, Stülpner became a father again. On June 7, 1835, the 24-year-old Auguste Wilhelmine Günther from Zschopau gave birth to an illegitimate daughter named Amalie Aemilie, who died a few months later.

After Schönberg's book was printed, Stülpner received a share of the proceeds as well as a few copies at his own disposal. Peddling these books illegally, Stülpner was picked up by the police in Leipzig in early August 1835 and deported to his home town of Scharfenstein.

On October 5th, 1839, Stülpner was brought from Lauta to Scharfenstein because of old weakness and his lame leg . It was then up to the local council to provide for his livelihood. He was paid 6 groschen a week from the poor, and the local landlords had to take turns to house him for eight days each. On September 24, 1841, Karl Stülpner died of exhaustion, almost 79 years old. His grave in the Großolbersdorf cemetery has been preserved to this day.

filming

The seven-part series Stülpner-Legende des Fernssehen der DDR (1973) with Manfred Krug in the leading role depicts, in a free adaptation, some legendary episodes from Stülpner's life from around 1779 to 1795.

Honors

In 2000, the planetoid discovered on December 29, 1998 in the Drebach public observatory was named YH 27 after Karl Stülpner. It bears the official name (13816) Stülpner and moves between the planets Mars and Jupiter around the sun .

beer

The private brewery Olbernhau brews a strong beer named after Stülpner .

swell

- Klaus Hoffmann: Confiscated and Banned - Popular literature about the game shooter Carl Stülpner. in: Kulturbund der DDR (Ed.): Sächsische Heimatblätter . 20th year 1974, issue 6, pp. 241 to 267

- Johannes Pietzonka: Karl Stülpner - legend and reality. Sachsenbuch. Leipzig 1998. ISBN 3-910148-33-6 .

- Carl Heinrich Wilhelm Schönberg: Carl Stülpner's Strange Life and Adventure. Zschopau 1835 ( digitized version ). (Reprint Leipzig 1973).

- Karl Sewart : Nobody shoots me dead. The story of the folk hero Karl Stülpner. Chemnitzer Verlag. Chemnitz 1994. ISBN 3-928678-14-0 .

- Friedrich von Sydow: Carl Stülpner, a notorious poacher in the Saxon Ore Mountains. in: Freyberger non-profit news. Born in 1812, numbers 23 to 29 ( digitized )

Individual evidence

- ^ Freyberger charitable news. Born in 1812, No. 12 of March 19, 1812, p. 94, paragraph Announcements to the residents of Freyberg : Friedrich von Sydow announces that he will take up his post as commandant

- ↑ Stülpner Bräu strong beer. In: bierbasis.de. Retrieved August 8, 2016 .

literature

- Jens & Joerg G. Fieback: Audio book "Karl Stülpner - Robin Hood of the Saxon Forests", Zeitbrücke Verlag 2011, ISBN 978-3-9814717-0-0

- Kurt Arnold Findeisen : The son of the woods. The life novel of the robbery shooter Karl Stülpner. Leipzig 1934.

- Erich Loest : Stülpner novella. in: Erich Loest: Stage Rome. Ten stories. New life publishing house. Berlin 1975.

- Hermann Lungwitz : Old and new about Karl Stülpner. Use of Schönberg's notes. Löseke publishing house. Ehrenfriedersdorf 1887. ( Online on the website of the Saxon State Library - Dresden State and University Library )

- Eduin Milan: life, deeds and the end of Karl Stülpner's. Publishing house of the JG Walde'schen Buchhandlung. Löbau 1858.

- Wolfgang Riemer: True stories about Stülpner Karl. Tauchaer Verlag. Taucha 1993. ISBN 3-910074-15-4 .

- Friedrich von Sydow : The Wildschütz Carl Stülpner. Sondershausen 1832. ( digitized version )

- Max Wenzel : The Stülpner Karl. The story of the Erzgebirge game shooter. Sachsenbuch. Leipzig 1997. ISBN 3-89664-009-7 .

- Hermann Heinz Wille : The green rebel. New life publishing house. Berlin 1980. (Reprinted in: Erich Loest: Bauchschüsse. Ten stories. Linden-Verlag. Leipzig 1990.)

- Kai von Kindleben: Stülpner Karl: the Robin Hood of the Ore Mountains . staged his greatest adventures in a gripping way. Sutton, 2018, ISBN 978-3-95400-966-4 (photo book).

Web links

- Literature by and about Karl Stülpner in the catalog of the German National Library

- Literature by and about Karl Stülpner in the Saxon Bibliography

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Stülpner, Karl |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Stilpner, Carl Heinrich (real name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Erzgebirge folk hero |

| DATE OF BIRTH | September 30, 1762 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Scharfenstein |

| DATE OF DEATH | September 24, 1841 |

| Place of death | Scharfenstein |