Constitutional monarchy

|

|||||||

| Systems of government in the world | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||

| Last updated 2012 |

A constitutional monarchy , as a variant of the monarchy, is a form of government in which the monarch's power is regulated and limited by a constitution . The constitutional monarchy can be seen as a timeless form of government that still exists today; many constitutional monarchies are also parliamentary monarchies , because the representative body has the decisive influence on the formation of a government. Alternatively, one regards the constitutional monarchy as a historical transition form between the “ absolute ” and the “parliamentary” monarchy.

The constitutional monarchy was the most common form of government in Europe in the 19th century . Typical of a constitutional monarchy is a written constitution for the basic rules of the political system. On the basis of the constitution, a parliament is elected, which consists of two chambers. The monarch must cooperate with the parliament, either only in the area of legislation or also with reference to the executive branch.

Demarcation

The monarchies are often divided into absolute (without a constitution), constitutional (with a constitution) and parliamentary (the representatives of the people are determined by the formation of a cabinet). In most European countries, however, there has been no constant evolution from absolutism to parliamentarianism . Often there were changes and regression. It was possible that under the same constitution, sometimes the monarch, sometimes the parliament, had greater power, and a return to absolutism also occurred.

The constitutional monarchy usually differs from the absolute monarchy through a constitutional document . However, until today Great Britain has no uniform constitutional document, but only historical laws that have an impact on the political system. The British Parliament can change any law or resolution with a simple majority. Conversely, there were monarchies in which even a constitution did not significantly limit the power of the monarch. All of today's absolute monarchies have constitutions which, however, give the monarch unrestricted power.

The power of representation in the constitutional monarchy depends on several factors, including popular support and political unity. Even if the parliament is not explicitly involved in the formation of a government in a constitution, it can de facto exercise the decisive influence on it. In some countries, for example, in a constitutional struggle, the parliament no longer worked on the legislation and refused the monarch the desired state budget until the monarch set up a government with representatives of the people. The monarch then only appoints ministers whom he knows have the confidence of a majority in the parliament. A constitutional monarchy can therefore also be parliamentary (in the sense of forming a government).

In some cases parliamentarism is enshrined in the constitution itself. The representative body not only receives the usual control rights, such as the right to quote , with which it can summon a minister to a parliamentary session where he has to provide information. The parliament is expressly involved in the appointment of ministers, or in their dismissal, or in both. For example, the monarch appoints the ministers, but the people's representatives can use a vote of no confidence to show that they are rejecting a minister. The monarch then has to constitutionally dismiss him. Because of this risk, the monarch only appoints ministers who he already knows have a majority in the parliament.

prehistory

Ancient and Middle Ages

Control bodies of monarchs or rulers already existed in antiquity. In the history of Athens , after the abolition of the monarchy, the oligarchy of the noble families first developed . Finally, various structural reforms led to the development of classical Attic democracy . However, this had no crowned head as head of state.

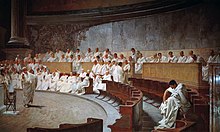

The Roman Senate was the most important institution of the Roman Empire until the end of the Republic . Not only the Senate as a body was responsible for this importance, also its members, the Senators, were always important and generally recognized persons in the Reich. Although the rights of the Senate, which was primarily an assembly of former officials, and the legal force of its decisions were never written down, it determined Roman politics up to the time of Augustus and in exceptional situations afterwards. The Senate existed during the Empire until the end of Late Antiquity , but it increasingly lost power over the emperors. The Byzantine Senate or Eastern Roman Senate was the continuation of the Roman Senate. It was founded by Emperor Constantine in the early 4th century . The institution of the Senate survived the centuries, although its relevance steadily decreased until it disappeared in the 13th century.

In Western Europe, feudalism developed after the fall of the Roman Empire. The elected German kings and Roman emperors were not tied to a senate or a parliamentary authority, but they had to pay attention to the opinion of the princes and could not rule absolutely. In 777, under Charlemagne, the first imperial assembly took place in Saxony (in Paderborn ). Since the 12th century, the formless court days developed into the Reichstag of the Holy Roman Empire and in 1495, by means of a contract between the emperor and the estates, became a permanent institution of the imperial constitution, corporations standing alongside the king or emperor . The Reichstag was originally the assembly of the imperial estates and developed into a decisive counterweight to the imperial central authority.

In France, the Estates General is the name given to the assembly of representatives of the three Estates, first convened in 1302 by King Philip IV . These consisted of the clergy , the nobility and the third estate . Each of these stands had around 300 delegates. The Estates-General were usually convened by the King in times of crisis, when the task was to enforce new taxes or to get contracts that were risky in terms of foreign policy. The origins of the assembly of estates lie in the ancient duty and the right of the nobility to advise the king. There were repeated attempts by the assembly to influence the royal legislation, but these were not very successful.

Development towards constitutionalism

Some of the origins of modern parliamentarism and constitutional monarchy are in England. The Magna Carta is an agreement signed by King John Ohneland of Runnymede in England on June 15, 1215 with the revolting English nobility. It is considered to be the main source of English constitutional law . A significant part of the Magna Carta is a literal copy of Henry I's Charter of Liberties , which granted the English nobility their rights. The Magna Carta guaranteed basic political freedoms of the nobility vis-à-vis the English king, whose land was fiefdom of Pope Innocent III. was. The church was guaranteed independence from the crown. The document was only accepted by the king after considerable pressure from the barons.

After the Magna Carta had receded into the background, its importance increased again in the 17th century when the conflict between the Crown and Parliament came to a head in the English Civil War . Through constant changes and additions, other strata of the population were granted rights and ultimately the constitutional monarchy was developed. It was not until the Bill of Rights in 1689 that large parts of the Magna Carta were replaced as a fundamental constitutional document. The Magna Carta, along with the Bill of Rights of England, is the basis of all United States law . In particular, the United States Constitution of September 17, 1787, refers in part to the fundamental rights set forth in these laws.

The constitution of May 3, 1791 of Poland-Lithuania ( Rzeczpospolita ) is considered the first modern European constitution in the sense of the Enlightenment. It established the first constitutional monarchy.

The French constitution of 1791 was passed by the constituent national assembly exactly four months after the Polish-Lithuanian constitution on September 3, 1791. With it, revolutionary France was transformed from an absolutist to a constitutional monarchy. However, this only lasted around a year. The Charte constitutionnelle had been the constitutional basis of the restored Kingdom of France since 1814 .

The history of the constitutional monarchy in the German states began in the years before 1800. Enlightened absolutism prevailed in many German states , a monarchy that aimed not only at the power of the state but also for the well-being of its subjects. The state should be modernized according to rational principles and “the class differences and barriers to activity that can no longer be reasonably justified should be abolished” (Dieter Grimm). That is why there was less pressure for reforms in Germany than in the ancien régime of France, where the monarchy largely rejected the Enlightenment. Nevertheless: In Germany, too, the monarchies were ultimately still absolute because the subjects received no political rights. People should live by the principles of the Enlightenment, not necessarily those that they chose.

At that time, the monarchy in Europe got into a serious financial and legitimacy crisis. As a rule, the aristocrats had to pay no or less taxes, the monarchs ran up debts, wars devastated the countries, and where there was a wealthy bourgeoisie they wanted to have influence on politics. After a lost war or a successful revolution , the king or the new rulers established a constitution for the following reasons:

- Financial policy: The wealthy citizens who paid taxes should have a say in what happened to the money. With a modern tax system that paid less attention to old privileges, more money could be made.

- Integration: The population or at least the upper class in newly conquered or affiliated areas was integrated into the state.

- Statehood: The constitutional state emphasized its sovereignty (independence) vis-à-vis other countries.

According to Martin Kirsch, the larger context of this development is state and nation building and democratization.

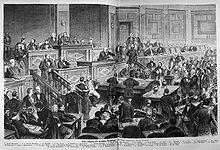

The constitutional monarchy in the proper sense is determined by a dualism , which can also be desired from the point of view of the separation of powers . Laws do not come into existence unless the monarch and the people's representatives agree; a government cannot govern effectively without laws and without a budget. The constitutional liberals in the Frankfurt National Assembly (1848/1849) definitely wanted a strong monarch to counterbalance the representation of the people: They were afraid of a pure parliamentary rule or even a reign of terror like in France in 1793/1794.

A dualism was permanently possible without automatically carrying the transition to parliamentarism (and with it its downfall). However, constitutional monarchies could become unstable or fail if the monarch closed himself off to dualism. Ultimately, the constitutional monarchy became a historical transition phenomenon because the democratic principle became overpowering in the 20th century. The monarch was left with almost only representative functions, or he was replaced by an elected president. However, if democratic control was not recognized, further development could lead to an authoritarian regime .

Main themes

Monarchical principle

The sociologist Max Weber distinguished three forms of rule. In relation to the monarchy this means:

- The monarchy was mostly understood as a traditional rule. The foundations were the historical age of many dynasties and the divine right : God created the world and divided people into classes. Such arguments lost strength in a rational and secular age, and some monarchs undermined this principle themselves when they appointed or removed other monarchs.

- The rule of kings was rational if it fulfilled a certain function within enlightened absolutism or a constitution. Socially the king was a mediator between different population groups, or a bulwark of the upper class against social demands. The king became a constitutional body that was no longer tied to a specific dynasty (and thus possibly even removable). If one set a rational yardstick for the functioning of the monarch, ultimately a removal or replacement came within the realm of the conceivable.

- A charismatic leader emerged in a crisis and promised to solve the country's problems. The legitimation was possibly reinforced pseudo-democratically by plebiscites . The most famous examples are Napoleon I and Napoleon III. However, social unrest, crises or military defeats endangered such legitimation.

In the 19th century, despite the beheading of the French King Louis XVI. in 1793, the (constitutional) monarchy was a widespread form of order and consciousness. Between 1815 and 1870, only one major country in Europe did not have a monarchy: Switzerland. Jürgen Osterhammel even writes of "reinventing the monarchy", for example in the colonial empires to which the constitutional monarchy was exported, but also with the revaluation of the British monarchy; with the empire of Japan, which was upgraded as a legitimation donor by an actually usurpatory regime; the federally constituted German Empire, in which Wilhelm I played a similar integrative role, but without a quasi-religious imperial cult; and with the Caesarist and Bonapartist empire of Napoleon III, "who could never make you forget that he did not come from one of the great ruling houses of Europe."

Ministerial responsibility

Traditionally, the monarch ruled with ministers whom he could remove and appoint as his personal servants. His cabinet with the ministers was ultimately just an auxiliary body. In the constitutional monarchy, the ministers were given a more independent role, either at the beginning of a constitutional order or later through a constitutional amendment.

This independence was based on ministerial responsibility, which was implemented in different ways in the constitution or in constitutional reality. This principle divided the monarchical government into a permanent and irresponsible part, the monarch; as in absolutism, he could not be deposed or called to account. The other part of the government was interchangeable and responsible, the ministers. An act of the monarch, such as an order or an ordinance, only became effective when a minister had also added his signature (the contraseign , the countersignature). The minister thus assumed responsibility and could possibly be prosecuted if he violated a law or the constitution.

If a minister did not agree with an act of the monarch, he did not countersign; although the minister could still be dismissed by the monarch, ministerial responsibility strengthened his independence because the monarch did not want to lose capable ministers. But the constitutional monarchy was also strengthened in this way because the people's representatives were mostly content with the removal of a responsible minister without immediately seeking the removal of the monarch (the ministers, according to Wolfgang Reinhard, were "lightning rods for the opposition").

Political or parliamentary responsibility is distinguished from more legal or criminal responsibility. The latter means that the parliament could de facto or de iure overthrow a minister if it no longer considered his work to be "expedient" politically. There are different formulations in the constitutions, even the separation into legal and political responsibility is not always clear. In some constitutions it was simply stated that the ministers were "responsible", but not to whom, for what and what the consequences were. For the development of parliamentarism, however formulated ministerial responsibility was ultimately not absolutely necessary and certainly not sufficient.

Popular representation

Before constitutionalism, European monarchies were seldom “ autocracies ”, like Russia before 1906 or France during the last years of Napoleon Bonaparte's rule . With the exception of fully developed absolutist monarchies, representatives of the estates had a large say in legislation, tax collection, and some military issues. Representative constitutions emerged around 1800 that provided for modern representation of the people. It was modern when the deputies were not sent by a class defined group of the population, such as the nobility or professions, but were elected by the people .

The representative bodies of the constitutional monarchy, however, differed greatly from today's purely democratic parliaments. Almost all of these representatives of the people consisted of two chambers each, i.e. two groups of members who met separately and were organized separately. One chamber was elected by the people and was called the Lower House , People's Chamber, People's House, House of Representatives, Second Chamber, etc. The other chamber was called Upper House , Manor House, First Chamber, etc. One-chamber systems were more common in very small states, or in the plans of the Democrats.

As a rule, the House of Lords served to integrate class elements into the parliament and to partially secure noble privileges. This should strengthen the conservatives loyal to the king . Members of the House of Lords were appointed by the king, or posted by a professional organization or university or church, or elected by wealthy landowners; or certain members of the high nobility were members by birth. The House of Lords could serve to give mediatized ex-princes a role. Each country had its own “mix” in the upper house.

The lower house was elected, but only by parts of the people. A census right to vote excluded all citizens who did not pay a minimum amount of taxes. A three-class suffrage allowed all citizens to vote, but gave the votes of the rich upper class more weight. In some states, the wealthy, the elderly, or academics had additional votes. There was seldom a universal and equal right to vote. In general, only men were allowed to vote, and because of the age structure of society at the time, a minimum age limit of 25 or 30 years excluded many possible voters from voting.

In a constitutional monarchy, a law was only passed if both the parliament and the monarch consented. The same applied to the state budget, i.e. income and expenditure. Similar to the formation of a government, legislation was a power game in which sometimes the monarch and sometimes the parliament could better assert themselves. It was often a big problem for the parliament that certain areas of politics such as foreign policy and the military were reserved for the monarch anyway. Parliamentary control in these areas was particularly difficult to implement.

European and German development

Although some European monarchies were subject to control mechanisms of the estates or the nobility, there was no summarizing constitution or constitution that defined the political process and regulated the separation of powers in a summarizing work. With the beginning of the Enlightenment in the 17th and 18th centuries, there were increasing efforts to define and regulate the power of the monarch in a constitution.

The oldest constitution of a constitutional monarchy is the constitution of May 3, 1791 of Poland-Lithuania ( Rzeczpospolita ), which is the first modern constitution in Europe in the sense of the Enlightenment.

The second oldest constitutional monarchy is the French from 1791 . France had a particularly large number of regime and constitutional changes until 1877; Constitutional kingship was ended three times: in 1792, 1814 and 1830. The structure remained monarchical: even when France had a consul or a president, this was hardly deductible in practice (like Napoleon Bonaparte and Louis Napoleon). The monarchies failed when there was a lack of willingness to democratize the right to vote, i.e. when broad sections of the population were excluded from political participation, when economic crises arose (1830 and 1848) or after war defeats (1814 and 1870).

France was a constitutional model because it formed many constitutions early on, but also “exported” constitutions through wars of conquest. Later constitution makers in other countries chose a constitution that appealed to them most. That of 1814 provided for a strong monarch, as befitted the spirit of the time. If they wanted a stronger parliament, they orientated themselves on that of 1791 or 1830. The European monarchies, on the other hand, found it difficult to tie in with the American republican constitution.

The Dutch monarchy was established in 1814/1815. In spite of the constitution, the kings ruled very independently until the middle of the century, until the representatives of the people slowly became more powerful. Parliamentarism was established in political culture in the 1860s, and in 1918 the right to vote was democratized. To this day, nowhere in the constitution of 1815 does it say that a minister would have to resign because the representatives of the people demanded it; in practice, however, it would hardly be conceivable that a minister would remain in office after a vote of no confidence.

The first modern German constitutions were issued by the French rulers in satellite states such as the Kingdom of Westphalia (1807). It is controversial to what extent it was a matter of pure “pseudo constitutionalism” ( Ernst Rudolf Huber ) or substantial, if only partially effective, constitutional orders. Actual constitutionalism began after the Napoleonic era in southern Germany (for example in Bavaria in 1818 ).

After a violently suppressed attempt in 1848/1849 to establish a German Empire as a constitutional monarchy, the empire was again founded in 1871 as a constitutional monarchy. Although the Federal Chancellor or Reich Chancellor was responsible, for a long time the results of the Reichstag elections were at most taken into account for the formation of a government. From October 1917 the governments were de facto dependent on the confidence of the Reichstag, and from October 1918 as a result of the October reforms, also according to the amended constitution. With the November Revolution shortly afterwards, the constitutional monarchy ended in all of Germany.

Martin Kirsch deals with the question of whether there was a special German path in the 19th century, whether Germany was “late” in this sense. From 1814/1815 France, the Netherlands and southern Germany were at the same stage of development in the constitutional monarchy, with a strong monarch and little influence from parliament. The absolutist states of Prussia, Sardinia-Piedmont and Denmark caught up from 1848. In comparison to the France of Napoleon III. Parliament was more important in Prussia.

From the year 1869/1870 France, Prussia and Italy had a similar level of development. "In none of the three countries had the link between democracy and parliamentarism in the constitutional state succeeded," in none had social justice been realized. A conflict between the representatives of the people and the monarch did not lead to a strengthening of the representation of the people in Prussia or Denmark, the Italian king dismissed Cavour in 1859 despite a parliamentary majority. Even later, the Italian parliament did not oppose such action. "The willingness of a parliament to conflict is only of limited use as a yardstick for assessing German constitutional characteristics." The monarch in Germany had great power, as in Sweden until 1917 and in Austria until 1918 , but normal in almost all countries. The Belgian king even had far more factual decision-making authority than the German emperor.

The framework conditions of the German constitution were very European, and a different development would have been possible. Germany really differed profoundly only in its federalism, which only Austria knew of the other constitutional monarchies. Kirsch: "The respective nation-state developments of monarchical constitutionalism in the 19th century cannot be divided into clearly delimited light and dark national 'special paths', but depending on the point in time individual paths approached or diverged again."

See also

supporting documents

- ↑ Martin Kirsch: Monarch and Parliament in the 19th Century. Monarchical constitutionalism as a European type of constitution - France in comparison . Vandenhoeck & Rupprecht, Göttingen 1999, pp. 386/387.

- ^ Rudolf Schieffer : Christianization and empire formations. Europe 700–1200. Munich 2013, p. 37.

- ↑ Dieter Grimm: German Constitutional History 1776-1866. From the beginning of the modern constitutional state to the dissolution of the German Confederation . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1988, pp. 49/50.

- ↑ Martin Kirsch: Monarch and Parliament in the 19th Century. Monarchical constitutionalism as a European type of constitution - France in comparison . Vandenhoeck & Rupprecht, Göttingen 1999, p. 386.

- ↑ Martin Kirsch: Monarch and Parliament in the 19th Century. Monarchical constitutionalism as a European type of constitution - France in comparison . Vandenhoeck & Rupprecht, Göttingen 1999, p. 410/411.

- ↑ Wolfgang Reinhard: History of State Power. A comparative constitutional history of Europe from the beginning to the present. 3rd edition, CH Beck, Munich 2002 (1999), p. 430.

- ↑ Martin Kirsch: Monarch and Parliament in the 19th Century. Monarchical constitutionalism as a European type of constitution - France in comparison . Vandenhoeck & Rupprecht, Göttingen 1999, pp. 389/390.

- ↑ Jürgen Osterhammel: The transformation of the world. A history of the 19th century , CH Beck: Munich 2009, p. 829/835.

- ↑ Jürgen Osterhammel: The transformation of the world. A history of the 19th century , CH Beck: München 2009, pp. 839, 841–844.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789 . Volume I: Reform and Restoration 1789 to 1830 . 2nd edition, Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1967, pp. 338/339.

- ↑ Wolfgang Reinhard: History of State Power. A comparative constitutional history of Europe from the beginning to the present. 3rd edition, CH Beck, Munich 2002 (1999), p. 429.

- ↑ Jürgen Osterhammel: The transformation of the world. A history of the 19th century , CH Beck, Munich 2009, pp. 839, 835.

- ↑ Dieter Grimm: German Constitutional History 1776–1866. From the beginning of the modern constitutional state to the dissolution of the German Confederation . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1988, p. 45.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789 . Volume I: Reform and Restoration 1789 to 1830 . 2nd edition, Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1967, p. 343.

- ↑ Martin Kirsch: Monarch and Parliament in the 19th Century. Monarchical constitutionalism as a European type of constitution - France in comparison . Vandenhoeck & Rupprecht, Göttingen 1999, pp. 387-389.

- ↑ Martin Kirsch: Monarch and Parliament in the 19th Century. Monarchical constitutionalism as a European type of constitution - France in comparison . Vandenhoeck & Rupprecht, Göttingen 1999, p. 402.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789 . Volume I: Reform and Restoration 1789 to 1830 . 2nd edition, Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [ua] 1967, p. 88.

- ↑ Martin Kirsch: Monarch and Parliament in the 19th Century. Monarchical constitutionalism as a European type of constitution - France in comparison . Vandenhoeck & Rupprecht, Göttingen 1999, pp. 395/396.

- ↑ Martin Kirsch: Monarch and Parliament in the 19th Century. Monarchical constitutionalism as a European type of constitution - France in comparison . Vandenhoeck & Rupprecht, Göttingen 1999, pp. 396-399.

- ↑ Martin Kirsch: Monarch and Parliament in the 19th Century. Monarchical constitutionalism as a European type of constitution - France in comparison . Vandenhoeck & Rupprecht, Göttingen 1999, pp. 399-401.

literature

- Martin Kirsch: Monarch and Parliament in the 19th Century. Monarchical constitutionalism as a European type of constitution - France in comparison . Vandenhoeck & Rupprecht, Göttingen 1999

- Christian Hermann Schmidt: primacy of the constitution and constitutional monarchy. An examination of the history of dogma on the problem of the hierarchy of norms in the German state systems in the early and middle of the 19th century (1818–1866) . (= Writings on constitutional history. 62). Berlin 2000. ISBN 3-428-10068-9

Web links

- Monarchy , on NetherlandsNet

- What is constitutional monarchy , at Royal.gov.uk