Art therapy

The art therapy is a young expressive therapy that derives of pulses from the US and Europe from the mid-20th century. Art therapy mainly works with media from the visual arts . This includes painting or drawing media, plastic-sculptural designs or also photographic media. With them, patients can express inner and outer images, develop their creative abilities and develop their sensory perception under therapeutic supervision .

The art therapeutic practice and theory building is with different disciplines such. B. connected to art history , psychology and education . In the last few decades, various forms and approaches of art therapy have developed from this. These have established themselves in clinical, educational or social fields of practice. Art therapy has gained particular importance in psychiatric, psychosomatic and psychosocial therapy practice.

history

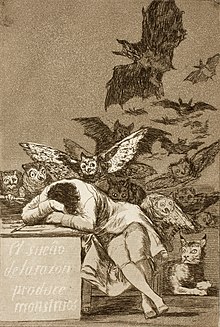

In art history there are parallels to the treatment of images in art therapy. Long before the discipline “art therapy” existed, visual artists dealt with inner images and their relation to reality. Examples are Francisco de Goya (1746–1828), Edvard Munch (1863–1944) and - more recently - Frida Kahlo (1907–1954).

Francisco de Goya has staged demons and monsters that rule the interior in a lithograph in the form of bats, owls and cats - animals of the night. The Capricho is entitled: "The sleep (dream) of reason creates (gives birth) monsters". The commentary on this sheet quoted by Lion Feuchtwanger reads: “As long as reason is asleep, the dreaming imagination creates monsters. Combined with reason, however, the imagination becomes the mother of the arts and all their marvels ”. In another translation it says: "The imagination, abandoned by the intellect (understanding, reason), produces monsters, united with it it is the mother of the arts".

With the two poles of fantasy and intellect , the title of the Capricho describes two essential conditions for artistic creation, in the area of tension in which art therapy as a therapeutic discipline has developed: between internal and external images, between production , i.e. the creative act, through the internal Images find expression and reception , the perception and appropriation of the designed work, by means of which the viewer gains an impression of the reality of the image.

development

Art therapy is a relatively young therapeutic discipline. It was not until the beginning to the middle of the 20th century that the first approaches to art therapy developed independently of one another in the English-speaking and European countries.

England and USA

In both England and the United States, art therapy has its roots primarily in art education , artistic practice, and developmental psychology . The terms art therapy and art education were not separated from each other in Great Britain until the 1970s. Here the term Art Therapy goes back to the painter Adrian Hill, who encouraged his fellow patients to do artistic work in a sanatorium where he was treated. This began his artistic work with patients, which he documented as a book in 1945 under the title Art Versus Illness . In the USA, the pioneers Margaret Naumburg and Edith Kramer (1916–2014) developed their art therapeutic approaches around the same time. In the late 1940s Margaret Naumburg developed " Psychodynamic Art Therapy " ( dynamically oriented art therapy ), while Edith Kramer derived art therapy from artistic practice ( art as therapy ). Their starting point was the art therapeutic work with children, which is documented in the book "Art as Therapy with Children", which is now part of the basic literature of art therapy. Joan Erikson began her arts therapy programs in the 1950s. Judith Aron Rubin sees herself with her work “Art Therapy as Child Therapy” as well as Helen Landgarten , who presented a concept of clinical art therapy.

From 1974 onwards Paolo Knill , Shaun McNiff and Norma Canner at Lesley University in Cambridge (USA) developed “ Expressive Arts Therapy ” as an intermodal and intermedia form , that is to say several arts, with the establishment of a master’s course in “Creative Arts Therapy” artistic therapy.

European and German-speaking areas

In German-speaking countries, the first approaches to art therapy are related to the development of anthroposophic medicine . In 1921 Ita Wegman founded a private clinic in Arlesheim , Switzerland, based on anthroposophical teaching, and from 1927 integrated artistic therapies such as visual design into clinical treatment with Margarethe Hauschka and Liane Collot d'Herbois .

Around the same time, there were the first impulses for the integration of visual design into the therapeutic care of psychiatry. In the 1920s, visual design in psychiatric hospitals attracted attention through publications by Hans Prinzhorn in Germany ( Bildnerei der Geisteskranken , Berlin 1922) and Walter Morgenthaler in Switzerland. In 1921 the psychiatrist Walter Morgenthaler dedicated the book A Mentally Ill as an Artist to Adolf Wölfli (1864–1930) and made him known with it. Adolf Wölfli left behind an extensive body of work and is now regarded as one of the most important representatives of the visual arts of “outsiders”. This not only paved the way for art therapy in psychiatry , but also had lasting effects on the visual arts, where it was known under the terms Art brut and later Outsider Art . One of the first to include artistic work in psychiatric treatment was the psychiatrist Leo Navratil (1921–2006), who encouraged his patients to engage in artistic activity and used it for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. In 1981 he founded the House of Artists on the grounds of the Gugging Hospital near Vienna as a center for art and psychotherapy.

The term Art brut goes back to Jean Dubuffet , who founded the Compagnie de l'Art brut in Paris in 1947. He thus opened the boundaries of the exclusive art business for “outsider art”, not without emphasizing that it was about the effect of art and not about establishing an “art of the mentally ill”. There is just as little "as an art for those with stomach problems or those with knee problems" . Rather, he was concerned with the sensual and aesthetic qualities of individual artistic expression, as expressed in the designs of laypeople, in the creations of the “mentally ill”, doodles by children or the designs of so-called primitive cultures . In the period that followed, various art movements such as action painting were fed from the new artistic possibilities of expression that were opened up for the visual arts . These developments not only changed the understanding of art, but also opened our eyes to the therapeutic potential of artistic design.

The direct, individual expression of inner images, the process-oriented understanding of artistic creation and the associated art movements form the art-historical context of art therapeutic practice and theory formation. Surrealism, which was founded by the French poet and critic André Breton in 1924, emphasizes the role of the unconscious and, in this, the dream as a source of artistic creation. In his tradition, Jackson Pollock (1912–1956), with reference to Carl Gustav Jung, sought a point of contact for the expression of the unconscious in Indian culture and mythology and developed action painting after 1946: “When I am in my picture, I am not myself conscious of what I am doing. ”In recent art history there is with Joseph Beuys (1921–1986) (“ Art is therapy ”) and the expanded concept of art that he proclaimed , which relates artistic practice to political, societal and social reality, a direct reference point for an art therapeutic practice that sees itself as social art . Another aspect was created by Wolf Vostell , who in 1961 declared life to be art with his premise life is art, art is life .

Other origins of art therapy, to which various current art therapeutic concepts refer, lie in pedagogy and curative pedagogy, art pedagogy and aesthetic education . Thus, at the center of various approaches in reform pedagogy from the first third of the 20th century is the conviction that self-reliant, creative activity is a basis for human development. In place of the strict separation of knowledge and experience, there is learning from the material through creative design. Art therapeutic concepts refer to this, for which the promotion of development, the promotion of social and creative abilities and the training and education of sensory perception are in the foreground.

Areas of application

Art therapy is practiced in clinical , educational , curative education or socio-cultural areas, e.g. B. in hospitals, schools, facilities for the disabled, museums, prisons, old people's homes, in counseling, team coaching, supervision, adult education and in independent counseling and therapeutic practice.

Art therapy is anchored differently in health care in Europe. In England, art therapy has already become an integral part of clinical settings. In 1990 a survey (Survey of Conditions of Service of Registered Art Therapists) found that 54% of 64.4% of the art therapists surveyed work in the health sector, 15% in the social sector and 7% in the education sector. As a consequence, since 1997 the profession of “art therapist” has been legally regulated and registered by the state in England by the law “Act of Professions Supplementary to Medicine”.

In Germany, art therapy is not legally protected in this way. However, in recent years art therapy has become a component of the psycho-social offer in the inpatient and outpatient as well as in the preventive , acute medical (e.g. coping and coping with illness) and rehabilitative areas in clinical-medical treatment concepts . It is used here for disease prevention, acute disease management and rehabilitation. Its field of application currently extends from psychiatry to psychosomatics , oncology / hematology , (social) paediatrics to neurology and geriatrics . Here there are already elaborated guidelines that have led to the integration of art therapy into the case flat rate system ( diagnosis-related groups , diagnosis- related case groups, DRG) with its own individual number and as an element of an "integrated psychosocial complex number".

In addition to working with children, adolescents and adults in clinical, but above all in educational or other social contexts, art therapeutic work with old people and in clinical and outpatient practice with cancer patients is well established. In psycho-oncological treatment, psychosocial stress and coping , i.e. coping with difficult life situations, play a central role. There is a close connection between somatic therapy management and subjective psychological well-being in cancer patients. In this context, art therapy methods have been integrated more and more into cancer therapy. In addition to the therapeutic approach of art therapy, salutogenesis is playing an increasingly important role. As a cognitive and emotive-forming medium, art therapy has a resource-activating influence on the strengthening of resilience (= mental and spiritual resistance). In health culture, it makes an important contribution to personal, social and economic health. A new field of art therapy opens up here, e.g. B. in workplace health promotion.

There are individual case studies in numerous clinical areas of application of art therapy, but without empirical findings on the effectiveness of art therapy, since artistic-creative processes are often difficult to map with the means of evidence-based medicine . With regard to clinical-medical fields of application of artistic therapies, there are a number of studies with positive results in the treatment of acute and chronic pain disorders ( fibromyalgia ) or in children with leukemia . Other efficacy studies show a significant reduction in physical symptoms and psychological abnormalities in psychosomatics . An examination of the clinical results and the costs of anthroposophic therapies, including “anthroposophic art therapy” in patients with chronic illnesses, has proven the long-term improvement of chronic illnesses and the health-related quality of life while at the same time reducing treatment costs. An evidence-based, empirical-quantitative effectiveness analysis in the clinical area of patients in alcohol addiction treatment shows significant results and effect sizes due to the positive influence of multimedia, art therapeutic processes - including on the fulfillment of meaning and the expectation of self-efficacy. The development process of resilience contributes to the basic skills to cope with crises with the help of one's own resources. The attitude of personal responsibility and initiative to goal-oriented, forward-looking independent action and solving different tasks is promoted by art therapeutic interventions.

description

Basics

Art therapy differs from other forms of therapy in that a third element is added to the patient-therapist relationship: the artistic medium. This results in a relationship triangle between the relationship points client - therapist - medium (work), which is referred to in art therapy literature as the art therapy triad. Thus, three levels and their relationship to one another play a role in art therapeutic practice: the artistic design of the work, the relationship between therapist and patient, and the consideration of the work and its effect. This results in a complex number of interaction constellations. The work itself takes on a multi-dimensional meaning as well as the function of a communicative third party, which is created by the client and can be actually perceived.

Art therapeutic practice finds its scientific or humanistic justification in different disciplines. It can be based on the principles of psychoneurology, cognitive science, phenomenology, psychotherapy research, synergetics, psychoanalysis , analytical psychology , humanistic psychology , cognitive behavioral therapy or systemic therapy , or it can be based on anthroposophical assumptions .

Some depth psychological approaches to therapy that work with the means of fine arts use the term painting therapy or creative therapy in place of the term art therapy . The term painting therapy is used for both depth psychology and anthroposophical approaches to art therapy that relate exclusively to painting. In the art therapy is a psychodynamic approach of art therapy practice, working in the true artistic media, designs but not from the therapy as art are referred. In this context, creative therapy must be fundamentally differentiated from Gestalt therapy , which is a special psychotherapy procedure that understands the connection between body, mind and soul as a whole figure .

Setting

Art therapy can take place in different settings , depending on the field of practice it takes place, the methodological approaches it follows or the indications . It is offered as individual or group therapy as well as individual therapy in groups. It can take place in open studios as well as in closed groups or in the protected framework of individual therapy. Various materials such as liquid or solid paint, clay, wood or stone, e.g. B. soapstone , are used. With the different conditions, different effects come to the fore, such as the individual self-experience at work, the effect of social interaction in the group or the sensual examination of the specific medium. Topics and materials can be given or freely chosen.

Mode of action

Art therapy works with visual media such as color, line, clay, stone or photography, through which the patient expresses himself. It is about his inner images, his view of the world, the development of new skills and room for maneuver and the discovery of possible solutions and resources. In addition to depth psychological concepts that deal with the causes of mental disorders , solution-oriented concepts play a role in other art therapeutic approaches, which in the sense of salutogenetically oriented medicine do not ask about the causes of the disease but about the causes of health.

In depth psychological art therapy, inner images play a role that are expressed in the designs. Inner images associated with crisis situations or traumatic experiences can trigger mental disorders. Such images can gain an immediate sensual presence in artistic designs, through which the patient can enter into a creative dialogue with them. He stands opposite the painted or drawn picture, he can transform it so that a new picture can take the place of the burdensome (inner) picture: “Therapy is about becoming aware of inner processes, about more awareness. That means to a more intensive listening in or looking into the intrapsychic world with all the feelings that it triggers, and then again about a step back, which makes it possible to recognize the patterns and rules that influence internal and external actions and them to relieve them of their constraints ... ” (Elisabeth Wellendorf).

What is expressed through the creation of images in art therapy is not always an expression of inner images that belong to the unconscious. You can also cover them up, go back to cultural conventions, aesthetic models, concepts or schemes .

Solution-oriented forms of art therapy focus more on the skills that can be developed through artistic design. Visual design also offers the opportunity to tell stories through pictures, to give shape to moods in the picture, to train the eye for aesthetic phenomena or to experience the sensual effect of aesthetic designs. Art therapy can thus serve to promote development , self-fulfillment , the promotion of social and creative abilities and the training and education of sensory perception (" sensory integration ").

Art therapeutic approaches

The distinction between clinical-medical, social, curative and special educational, as well as psychotherapeutic concepts and approaches to art therapeutic practice is relatively new nationally and internationally. The different art therapeutic approaches go back to different lines of development, to different fields of application and different sciences. They are based either on depth psychological theories, on art and image sciences , on anthropological or philosophical assumptions or on social science theories. Art therapy thus has different and interdisciplinary starting points and references. As diverse as the context of the various art therapeutic approaches with reference to different fields of application, different reference sciences or related therapeutic methods, the concept formation in art therapeutic theory formation is just as heterogeneous. The distinction between different art therapeutic approaches is nothing more than a guide.

Karl-Heinz Menzen differentiates the art therapeutic approaches into the art psychological, the art pedagogical, the occupational therapy , the curative pedagogical-rehabilitative, the creative and creative therapeutic approach and the depth psychological approach. Baukus and Thies differentiate between the psychiatric, the artistic-educational, the curative educational, the psychotherapeutic, the anthroposophical, the receptive and the integrative approach.

Depth psychological and psychotherapeutic approaches

In depth psychological and psychotherapeutic approaches to art therapy, images are understood as visualizations of psychic events. The psychoanalytic art therapy goes to Sigmund Freud or Jung back, already a relationship between the pictorial and the " unconscious manufactured". In therapeutic practice, images can be the basis for interpretation ( image interpretation ) and the therapeutic conversation. CG Jung used that of the “ collective unconscious ” as the central term , which contains the impressions of all experiences in human history that precede the individual self . The archetypes are the individual elements that make up the collective unconscious and that are manifested in symbols , a kind of primitive imagery. Following on from this, depth psychological approaches in art therapy assume a connection between psyche and designed expression. After that, creative processes can trigger changes in people. In addition, artistic creation can make it possible to remember and integrate images that are part of our internal and external order.

Pedagogical, curative education or art educational approaches

The creative engagement with visual media goes back to the child's play, which is an essential condition for the child's development. This development is expressed in children's drawings , which reflect different stages of child development. The child's creative occupation with objects from his environment is a prerequisite for his healthy development. Here, pedagogical, curative or art-pedagogical approaches of art therapy refer to theories of psychology and developmental psychology . In terms of the history of philosophy, these approaches are related to Friedrich Schiller , who in his letters “ On the Aesthetic Education of Man ” (1795) established the view that man is realized in aesthetic action . In the 20th century, this found a response in reform education and finally in the Bauhaus and its concepts for cultural promotion and education of people.

With regard to pedagogical and curative educational approaches to art therapy, HG Richter introduced the term “educational art therapy” and KH Menzen introduced the term “curative educational art therapy”.

Anthroposophical approaches

Art therapy on an anthroposophical basis is based on anthropological assumptions and relates to physical and mental and spiritual gestalt processes that are stimulated by artistic creation. The basis is the anthroposophical image of man, which goes back to Rudolf Steiner . Anthroposophical art therapy relates the phenomena of gestalt formation to the polar forms of chaos and form, between which the rhythm creates a balance.

It relates to the therapeutic painting on the color theory of Goethe . Goethe describes the emergence of colors from the polarity of light (yellow) and darkness (blue) as a “primordial phenomenon” from which the psychological effects of colors (“sensual and moral effect of colors”) on people are based.

Plastic-therapeutic design is one of four basic forms of anthroposophical art therapy approaches (music therapy, therapeutic speech design, painting therapy and plastic-therapeutic design). The material used here is mainly clay, but also materials such as stone or wood. Plastic design, like therapeutic painting, is seen in its effectiveness in connection with mental and spiritual processes.

There are different orientations within anthroposophic art therapy, some of which have developed different methods.

Art-oriented and art-based approaches

Art-oriented and art-based approaches to art therapy are both cultural-philosophical as well as anthropological and philosophical . An intermodal variant of art therapy called “ Expressive Arts Therapy ” was developed in the USA in the 1970s under the heading of “art-oriented action” in support of change processes. As an intermodal therapy, Expressive Arts Therapy incorporates not only the visual arts into therapeutic practice, but also other arts such as dance, drama, music or poetry. In Germany, this therapeutic approach is known as " Intermedial Art Therapy ". In contrast to therapeutic approaches in which the emotional conflict from which the patient suffers is brought into focus, the Expressive Arts Therapy or Intermedial Art Therapy has a solution-oriented approach with the method of "intermodal decentering". “Decentering” means turning away from the actual problem and turning to new, aesthetic experiences. The turn to a creative and artistic activity should open up new solution possibilities and perspectives through an "alternative world experience", which the limited view of the problem area closes.

In Germany, artistically oriented approaches to art therapy are established as “ art in the social ” and go back to the anthropological and aesthetic reception theory in the arts and visual sciences , for example in Rudolf Arnheim's theoretical foundation : “All perception is also thinking, all thinking is also intuition, all observation is also inventing ” (in:“ Art and Seeing: A Psychology of the Creative Eye ”). For artistically oriented therapy approaches, artistic action itself is therefore considered to be a direct source of knowledge and insight that can be accessed through sensual experience. In addition, anthropologically based approaches to art therapy refer to an expanded concept of art . The associated understanding of therapy goes beyond an understanding of therapy in the narrower medical-clinical sense and means, in the sense of its origin from the Greek (θεραπεία (therapeía) = serving, to therapy: serving, healing, nurturing) the accompaniment and support of the other person seeking help. This understanding of therapy is related to the client-centered psychotherapy developed by Carl Rogers , in which the focus is on the relationship between client and therapist. Artistically oriented approaches of art therapy that focus on the relationship between client and therapist therefore understand therapeutic action as artistic action in the relationship with another person.

Art therapeutic methods

Art therapeutic methods can - as in depth psychological approaches - use artistic design as an opportunity to diagnose and talk about emotional conflicts; they can - as in process-oriented approaches - bring the therapeutic aspect of artistic activity to the fore or they can - in receptive approaches - take the effect of the medium on the client as the starting point for art therapeutic practice.

Talking about the work created in art therapy can help the patient to discover new perspectives and possible solutions. However, it is not primarily about interpreting pictures or translating pictures into words. Images cannot simply be read as text that lies behind them and gives them meaning. An exception are psychological test procedures carried out according to certain rules , which are more likely to be used in psychological diagnostics .

Art therapeutic methods can stimulate creativity through the specific setting , but they can also relate to the immediate, more relieving or structuring effect of the design media, such as B. watercolors, crayons or plastic means of expression (clay or stone), develop sensory skills, act on acquired behavioral patterns and promote social, interpersonal skills.

Drawing tests

Drawing tests are used for diagnostics and require the therapist to have a psychological qualification. The projective methods of investigation are considered

- the representation of the family in animals , in which the test person is supposed to draw his family members as animals,

- the Rorschach test (also: ink blot test), for which Hermann Rorschach developed his own personality theory,

- the thematic apperception test (TAT) and

- the Wartegg character test .

However, these tests are rated rather poorly in terms of their resilience ( validity ).

Messpainting

The “Messpainting” is supposed to stimulate creativity through spontaneous painting . Newspaper, finger, paste or emulsion paints, brushes are used. The basic rules are:

- It is painted very quickly (a picture is created about every two minutes until about 10-14 pictures are created),

- at least 80% of the newspaper sheets are covered with paint,

- the pictures arise from an uninhibited sequence of movements (it is not about painting beautiful pictures, the attention is on the painting process).

Expression painting

The expression painting is a method of painting by Arno Stern . He developed it in the 1950s while working with children, in which the creation of traces on a sheet of paper without artistic design intent as a "meaningful game" is in the foreground. The following rules apply:

- Painting is done with gouache paints by hands or a brush.

- The room in which you paint should be protected.

- It is painted while standing.

- The process of painting, but not the result , is in the foreground (there is no such thing as “beautiful” or “ugly”).

Related to expressive painting is “accompanied painting” according to Bettina Egger .

Accompanied painting

Accompanied painting according to Bettina Egger is an independent art therapeutic method that has been developed from expressive painting according to Arno Stern since 1965 . The name of the method implies accompanying the painting person while creating a picture. This way of working is based on the assumption that the direct effect of painting and the painted picture stimulates and promotes the self-healing powers of the painter.

Shape drawing

Shape drawing is a method stemming from Waldorf education and widely used in anthroposophical art therapy . The model for form drawing is the art of the Celts and the "Ars lineandi" in the stone carving art of the Lombards and Irish.

The means of drawing shapes is the line as a trace of movement. The sequence of movements is structured rhythmically and moves between the poles of “binding” and “loosening”, such as B. with so-called braided ribbons. As a rule, the patient is asked to actively follow the predefined lines from the free movement. The rhythm between the two poles of consolidation and dissolution should create a balance.

Work on the clay field

Working on the clay field is an art therapeutic method patented by Heinz Deuser. The clay field consists of malleable clay in a wooden box. The patient is asked to perceive the sound and, if possible, to shape it with his eyes closed. In the “action dialogue” of the hands with their own traces, the movement should act as a formative force on the patient and on acquired patterns of action .

Dialogic painting

Dialogic painting is mainly based on pedagogical, curative pedagogical or art pedagogical approaches. The dialogue develops non-verbally between two people, possibly between therapist and client, in the creation of a common image. The picture can lead to a "representational" representation that tells a story or to an "abstract" composition in which shapes, lines and colors relate to one another. In addition to initiating and promoting creative processes, the focus here is on developing, designing and making social interactions visible .

Art therapy job description

Art therapy is recognized and regulated differently in different European countries:

- In Germany there is no uniform professional profile for art therapy. There are art therapy courses at universities, technical colleges and private training institutes. Four-year, undergraduate courses are offered at universities of applied sciences and postgraduate courses in art therapy are offered at universities and art colleges. They conclude with either a diploma or a bachelor's or master's degree . In addition, private training institutes offer full-time and part-time training. The professional and professional associations have developed different training standards for this purpose, which are a prerequisite for membership. There are no uniform and binding standards for universities or private training institutes.

- In Austria and Germany, art therapy cannot be described as psychotherapy .

- In Austria there is currently (as of 2017) a procedure for the recognition of art therapy as an independent job description in the health sector.

- A charter was signed in Switzerland in 1993 that defines the basic positions of the most important psychotherapy methods in Switzerland. The charter was developed in a process that involved 1,700 psychotherapists. In 2002 seven professional associations for artistic therapies merged to form an umbrella organization, the “Conference of the Swiss Art Therapy Associations KSKV / CASAT”, with the aim of achieving state recognition through a higher professional examination. On March 18, 2011, the higher professional examination (Federal Diploma (ED)) for art therapists was approved by the Federal Office for Professional Education and Technology (OPET) in Switzerland and thus the professional title: Diplomierte Kunsttherapeutin (ED) / Diplomierte Kunsttherapeut (ED) accepted. The job title relates to five specific disciplines: movement and dance therapy, drama and speech therapy, design and painting therapy, intermedia therapy and music therapy.

- In 1997, the profession of art, music and drama therapist was registered in Great Britain.

See also

- Creative therapy

- Expressive Arts Therapy

- Cultural therapy

- Painting therapy

- Expression painting

- State-bound art

- Aesthetic education

- Art in the social

- List of universities for art therapy in Germany

- List of further training courses for art therapy in Austria

literature

- Karin Dannecker: Psyche and Aesthetics. The Transformations of Art Therapy. 3. Edition. Medical Scientific Publishing Company, Berlin 2014, ISBN 978-3-95466-125-1 .

- Christine Leutkart, Elke Wieland, Irmgard Wirtensohn-Baader (eds.): Art therapy - from practice for practice. Verlag modern learning, Dortmund 2004, ISBN 978-3-8080-0526-2 .

- Phillip Martius, Flora von Spreti, Peter Henningsen (ed.): Art therapy for psychosomatic disorders. Urban & Fischer, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-437-23795-9 .

- Peter Sinapius, Marion Wendlandt-Baumeister, Annika Niemann, Ralf Bolle (eds.): Image theory and image practice in art therapy. Scientific foundations of art therapy. Volume 3. Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2010, ISBN 978-3-631-58659-4 .

- Flora von Spreti, Phillip Martius, Hans Förstl (eds.): Art therapy for mental disorders. Urban & Fischer, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-437-23790-X .

- Flora von Spreti, Philipp Martius, Florian Steger (eds.): Art Therapy / Artistic Action - Effect - Craft, Schattauer, Stuttgart 2017, ISBN 978-3-7945-3098-4 .

Trade journals and periodicals

- Art & Therapy. Journal of Artistic Therapies. Claus Richter Verlag, Cologne, 1997–, ISSN 1432-833X .

- Music, dance and art therapy. Journal of artistic therapies in education, social and health care. Hogrefe, Göttingen, 1988-, ISSN 0933-6885 ( hogrefe.com ).

- Series Scientific Basis of arts therapies. HPB University Press, Hamburg / Potsdam, Berlin.

- International Journal of Art Therapy. Inscape. Edited by the British Association of Art Therapists, 2005–, ISSN 1745-4832 .

- ARTherapy. Journal of the American Art Therapy Association, 1991–, ISSN 0742-1656 ( tandfonline.com ; previously udT: Art Therapy. Journal of the American Art Therapy Association, 1983 / 84–1991, ISSN 0742-1656 ).

- Poiesis. A Journal of the Arts and Communication, EGS Press, [verified from] 7.2005–, ISSN 1492-4986 .

- design process. Trade journal of the Association for Painting and Design Therapy - Vienna.

Movie

- Christian Beetz (director): Between madness and art. The Prinzhorn Collection. D, 2007, 75 min. Adolf Grimme Prize 2008

Web links

Outsider art

Children's drawing

- The development of children's drawings (gallery for children's drawings)

Individual evidence

- ↑ L. Feuchtwanger: Goya. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1998, p. 587.

- ^ W. Hofmann: Goya - The Age of Revolutions. Prestel, Munich 1980, p. 61.

- ↑ M. Bockemühl: The reality of the picture. Image reception as image production. Rothko, Newman, Rembrandt, Raphael. Urachhaus, Stuttgart 1985.

- ↑ a b K. Dannecker (Ed.): International Perspectives of Art Therapy. Nausner & Nausner, Graz 2003.

- ^ M. Naumburg: Dynamically oriented art therapy. Grune & Stratton, Inc., New York 1996.

- ^ T. Dalley: Art as Therapy. Brunner-Rontledge, London / New York 2004.

- ^ E. Kramer: Art as therapy with children. Ernst Reinhardt Verlag, Munich and Basel 1978.

- ^ JA Rubin: Art Therapy as Child Therapy. Geradi Verlag for Art Therapy, Karlsruhe 1993.

- ↑ HB Landgarten: Clinical Art Therapy - A Comprehensive Guide. Geradi Verlag for Art Therapy, Karlsruhe 1989.

- ^ P. Knill: Principles and Practice of Expressive Arts Therapy - Toward a Therapeutic Aestetics. Jessica Kingsley Publishers, London 2005.

- ^ Liane Collot d'Herbois: Light, darkness and color in painting therapy. Verlag am Goetheanum, Dornach 1993.

- ^ I. Marbach: 33 years of the Margarethe Hauschka School. Boll 1995. (Festschrift)

- ↑ H. Prinzhorn: Bildnerei the mentally ill. A contribution to the psychology and psychopathology of design. Springer, Berlin 1922.

- ^ W. Morgenthaler: A mentally ill artist as an artist: Adolf Wölfli. Medusa-Verlag, Vienna 1985.

- ^ L. Navratil: The artists from Gugging. Medusa, Berlin / Vienna 1983.

- ↑ a b R. Bader, P. Baukus, A. Mayer-Brennenstuhl (eds.): Art and therapy. An introduction to the history, method and practice of art therapy. Publishing house of the Foundation for Art and Art Therapy, Nürtingen 1999.

- ↑ Kammerlohr: Epochs of Art. Volume 5. Oldenbourg Verlag, 1995.

- ↑ J. Beuys: “Art is therapy” and “Everyone is an artist”. In: Hilarion Petzold (ed.): The new creativity therapies. Handbook of Art Therapy. Volume I. Junfermann, Paderborn 1990, p. 33.

- ↑ Wolf Vostell. Life = art = life . Art gallery Gera, EA Seemann, Gera 1993, ISBN 3-363-00605-5 .

- ↑ John Dewey: Democracy and Education. An introduction to philosophical pedagogy. Beltz, Weinheim and Basel 1993.

- ↑ C. Case, T. Dalley: The Handbook of Art Therapy. Routledge, London 2004, p. 6.

- ↑ F. von Spreti, H. Förstl (Ed.): Art therapy for mental disorders. Urban & Fischer, Munich 2005.

- ↑ P. Martius, F. von Spreti, P. Henningsen (ed.): Art therapy for psychosomatic disorders. Urban & Fischer, Munich 2008.

- ^ German Institute for Medical Documentation and Information (DIMDI): Classifications in Health Care ( Memento of March 8, 2008 in the Internet Archive ). 2007. In: dimdi.de, February 25, 2008, accessed on April 25, 2007 (with a link to the PDF; 580 kB ( memento from June 23, 2012 in the Internet Archive )).

- ↑ M. Ganß, M. Linde (Ed.): Art therapy with people with dementia. Mabuse-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2004.

- ^ W. Henn, H. Gruber (Ed.): Art therapy in oncology. Claus Richter, Cologne 2004.

- ↑ P. Sinapius (Ed.): “This is how I want to be.” Coping with the disease in cancer - images from art therapy. Claus Richter Verlag, Cologne 2009.

- ↑ C. Jakabos, P. Petersen: Art Therapy in Oncology: Results of a Literature Study. In: P. Petersen (Ed.): Research methods of artistic therapies - foundations, projects, suggestions. Mayer, Stuttgart / Berlin 2002, pp. 323-340.

- ↑ Eva Bojner Horwitz: Dance / movement therapy in Fibromyalgia Patients: Aspects and Consequences of Verbal, Visual and Hormonal Analyzes. Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis, Uppsala 2004 ( diva-portal.org [accessed April 29, 2008]).

- ↑ Favara-Scacco, Smirne, Schiliro, DiCataldo: Art Therapy as support for children with leukemia during painful procedures. In: Medical and Pediatric Oncology. Vol. 36, 4/2001, pp. 474-480.

- ↑ DM Plecity: The effect of art therapy on the physical and emotional well-being of the patient - a quantitative and qualitative analysis. Ulm University, 2006 (accessed April 29, 2008).

- ↑ HJ Hamre et al .: Anthroposophic therapies for chronic diseases: The Anthroposophic Medicine Outcomes Study (AMOS). In: E. Streit, L. Rist (ed.): Ethics and science in anthroposophic medicine. Contributions to the renewal of medicine. Verlag Peter Lang, Bern 2006, pp. 151-183.

- ↑ Jutta Dennstedt: The effect of art therapeutic interventions on the resources self-management, self-efficacy expectation and meaningful life in in-patient alcohol-dependent patients. An empirical-quantitative effectiveness analysis. Publishing house Dr. Kovač, Hamburg 2018, ISBN 978-3-8300-9788-4 .

- ↑ cf. P. Sinapius: Aesthetics of therapeutic relationships - therapy as aesthetic practice. Shaker Verlag, Aachen 2010, p. 43 ff.

- ↑ cf. u. a .: G. Schmeer: art therapy in the group; Networking, resonances, stratagems. Pfeifer at Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 2003.

- ↑ Constanze Schulze: Evidence-based research needs in art therapy: Development of a model and manual for the systematic description and investigation of interaction phenomena in groups (IiGART) . In: Monika Ankele, Céline Kaiser, Sophie Ledebur (eds.): Performing, recording, arranging: Knowledge practices in psychiatry and psychotherapy . Springer, Wiesbaden 2019, ISBN 978-3-658-20150-0 , pp. 257-270 , doi : 10.1007 / 978-3-658-20151-7 .

- ^ A. Antonovsky, A. Franke: Salutogenesis: for demystifying health. Dgvt-Verlag, Tübingen 1997.

- ^ E. Wellendorf: Psychoanalytic art therapy. In: Hilarion Petzold (ed.): The new creativity therapies. Handbook of Art Therapy. Volume I. Junfermann, Paderborn 1990, p. 301.

- ↑ a b K.-H. Menzen: Basics of Art Therapy. Reinhardt, Munich 2001.

- ↑ P. Baukus, J. Thies: art therapy. Gustav Fischer Verlag, Stuttgart 1997.

- ↑ Hilarion Petzold (ed.): The new creativity therapies. Handbook of Art Therapy. Volume I and II. Junfermann, Paderborn 1990.

- ↑ J. Jacobi: From the picture realm of the soul. Walter-Verlag, Ölten 1997.

- ↑ K. Dannecker: Art, Symbol and Soul. Theses on art therapy. Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2000.

- ↑ Methodical on this in Theodor Abt: Picture Interpretation. According to CG Jung and Marie-Louise von Franz . Living Human Heritage, Zurich 2005. ISBN 3-9522608-2-7 . See also Ingrid Riedel: Images in Therapy, Art and Religion. Ways of interpretation . Kreuz Verlag, Zurich 1988. ISBN 3-7831-0906-X . Revised, expanded edition Stuttgart, Berlin 2005. ISBN 978-3-7831-2507-8 .

- ↑ CG Jung: Archetypes. DTV, Munich 2001.

- ↑ E. Wellendorf: How do the pictures get into your head? In: P. Sinapius, M. Ganß: Basics, models and examples of art therapy documentation. Verlag Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2007, pp. 119–129.

- ↑ H.-G. Judge: The children's drawing. Development - interpretation - aesthetics. Schwann, Düsseldorf 1987.

- ↑ Donald. W. Winnicott: From Play to Creativity. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1987.

- ^ Jean Piaget: Psychology of Intelligence. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1980.

- ↑ H.-G. Richer: Educational art therapy. Publishing house Dr. Kovac, Hamburg 2005.

- ↑ a b S. Auer u. a .: Anthroposophic art therapy. Volume 2: Therapeutic drawing and painting. Urachhaus, Stuttgart 2000.

- ↑ M. Altmaier: Color - soul of nature and man. For therapeutic painting. In: Anthroposophic Art Therapy. Volume 2: Therapeutic drawing and painting. Urachhaus, Stuttgart 2003.

- ↑ R. Bader, P. Baukus, A. Mayer-burning chair (ed.): Art and therapy. An introduction to the history, method and practice of art therapy. Verlag der Stiftung für Kunst und Kunsttherapie, Nürtingen 1999, pp. 51–61.

- ↑ G. Ott, HO Proskauer (ed.): Johann Wolfgang Goethe: Color theory. Volume 1-5. Free Spiritual Life Publishing House, Stuttgart 1992.

- ↑ What is Anthroposophic Art Therapy (BVAKT) ®? In: anthroposophische-kunsttherapie.de, accessed on September 22, 2012.

- ↑ P. Knill: Art-oriented action in the accompaniment of change processes. Egis-Verlag, Zurich 2005.

- ↑ P. Sinapius (Ed.): Intermediality and Performativity in Artistic Therapies. HPB University Press, Hamburg, Potsdam, Berlin 2018

- ^ H. Belting: Bild-Anthropologie. Designs for an image science. Fink, Munich 2001.

- ↑ R. Arnheim: Art and seeing: A psychology of the creative eye. de Gruyter, Berlin 2000.

- ↑ P. Sinapius: Therapy as Image - The Image as Therapy. Basics of an artistic therapy. Publishing house Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2005.

- ^ Wiktionary: Therapy

- ^ P. Petersen: The therapist as an artist. An integral concept of psychotherapy and art therapy. Junfermann-Verlag, Paderborn 1987.

- ↑ CR Rogers: Development of Personality - Psychotherapy from the perspective of a therapist. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1973.

- ↑ P. Sinapius: Therapy as Image - The Image as Therapy. Basics of an artistic therapy. Verlag Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2005, p. 143 ff.

- ↑ M. Ganß, P. Sinapius, P. de Smit (eds.): "I like to see you speak so much". Language in the reference field of practice and documentation of artistic therapies. Publishing house Peter Lang, Frankfurt 2008.

- ↑ G. Schottenloher: Art and design therapy - A practical introduction. Kösel, Munich 1989, p. 50 ff.

- ↑ Arno Stern: The painting place. Daimon Verlag, Einsiedeln 1998.

- ↑ Bettina Egger: Understanding Images. Perception and development of visual language. 6th edition. Zytglogge, Bern 2001.

- ↑ R. Kutzli: Development of creative powers through lively form drawing. Schaffhausen 1985.

- ^ H. Deuser: Movement becomes shape. Doering, Bremen 2004.

- ↑ B. Wichelhaus: Dialogical design, art therapeutic exercises as partner work. In: Zschr. K + U. Special volume: children's and youth drawings. Friedrich, Velber 2003, pp. 153–157.

- ↑ See the list of universities for art therapy in Germany .

- ↑ P. Knill: What does art change in therapy, and how? In: P. Sinapius (Ed.): Fundamentals, models and examples of art therapeutic documentation. Scientific foundations of art therapy. Volume 1, Verlag Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2007, p. 58.

- ^ Conference of the Swiss Art Therapy Associations (KSKV): media release of March 28, 2011 ( gpk.ch [PDF; 109 kB]).