Hodgkin lymphoma

| Classification according to ICD-10 | |

|---|---|

| C81.0 | Lymphocyte-rich form |

| C81.1 | Nodular sclerosing form |

| C81.2 | Mixed-cell form |

| C81.3 | Lymphocyte poor form |

| C81.7 | Other form |

| C81.9 | not further described |

| ICD-10 online (WHO version 2019) | |

The Hodgkin's lymphoma ( synonyms are Hodgkin's disease , formerly Lymphogranulomatose or lymphogranuloma , including Hodgkin's disease ; English Hodgkin's disease , abbreviated HD or Hodgkin's lymphoma , abbreviated HL ) is a malignant tumor ( "malignant granuloma") of the lymphatic system . The disease manifests itself through painless swelling of the lymph nodes , accompanied by so-called B symptoms , such as alcohol pain , which is almost pathognomonic for this disease . In the microscopic tissue image, Hodgkin's lymphoma (also known as Sternberg's disease ) is characterized by the presence of a special type of cell ( Sternberg-Reed cells ) , which distinguishes it from non-Hodgkin's lymphomas . Patients are treated with standardized therapy schemes using a combination of chemotherapy and radiation . The chances of recovery are good to very good, especially for children. The disease was named after the English doctor Thomas Hodgkin (1798–1866), who first described it in 1832 .

Epidemiology

The frequency of new cases ( incidence ) of Hodgkin lymphoma is two to four cases per 100,000 people, the ratio of men to women is 3: 2. In the industrialized countries there are two disease peaks in the age distribution, a larger one in the third and a somewhat smaller one in the seventh decade of life, while in developing countries the first disease peak is typically postponed to early childhood. In the industrialized countries (Europe, North America), a slight decline in the number of new cases can be observed.

In children and adolescents in Germany, Hodgkin's lymphoma occurs with a frequency of 0.7 cases per 100,000 children and adolescents aged up to 14 years. In comparison, the corresponding worldwide rate is 0.6 cases per 100,000. The ratio of boys to girls is analogous to adulthood. The mean age of onset is 12 years and 6 months, the maximum age is in the age group from 10 to 14 years. Children under four years of age are rarely affected by Hodgkin's disease, and the number of sick boys in this age group exceeds that of girls many times over.

root cause

The etiology (cause) of Hodgkin's lymphoma has not yet been adequately clarified. Many disease triggers have been discussed in the past. It is suspected to be caused by the oncogenic (cancer-causing) Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), as the risk of developing Hodgkin's disease increases approximately three times after a previous Pfeiffer glandular fever (infectious mononucleosis) caused by the EBV is. The Epstein-Barr virus can be detected in the lymphoma cells of 50 percent of the sick in industrialized countries; in developing countries this rate is over 90 percent. Conversely, almost everyone becomes infected with EBV at some point in their life; by the age of 30, the infection rate is over 95 percent.

Disorders of the immune system play an important role in the development of Hodgkin's disease. In the context of the increasing use of immunosuppressive (immune system suppressing) therapies - for example after transplantation of organs, bone marrow or blood stem cells - an increased incidence of Hodgkin's disease has been reported.

Infection with the HI virus also carries an increased risk of developing Hodgkin lymphoma, as does increased exposure to toxic substances, for example from wood preservatives.

At the end of 2005, molecular mechanisms for pathogenesis were proposed in various papers . Mathas and colleagues identified a disorder of the transcription factor E2A as a possible cause of an incorrect differentiation of the B lymphocytes. Another group published the degradation of the tumor suppressor gene Rb by the latent antigen 3C of the Epstein-Barr virus in various tumors.

The exact cause is still unknown and hardly the subject of current research, since the majority of research is not aimed at searching for the cause, but rather on therapy optimization. A possible vaccination against EBV, in order to eliminate this factor of development or to gain further knowledge about its significance, is in the development phase.

pathology

|

|

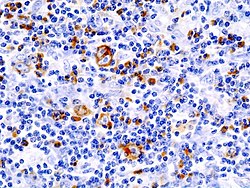

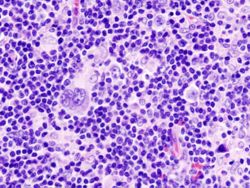

| immunohistochemical staining ( CD 30) | HE staining |

|

Histological sections of an affected lymph node (mixed cell form). The prominent cells with multiple, bright nuclei with distinct nucleoli are Sternberg-Reed cells. |

|

The mononuclear Hodgkin cells and the multinucleated Sternberg-Reed giant cells , often also referred to as Hodgkin-Reed-Sternberg cells (HRS cells) , are characteristic of the histological (tissue-based) diagnosis of Hodgkin lymphoma . These originate from the B lymphocytes (white blood cells) from the germinal centers of the lymph nodes. They are the actual malignant (malignant) growing cells of Hodgkin's lymphoma and multiply monoclonally (derived from a cell). Typical for Sternberg-Reed cells is the size of the cell of over 20 µm with several bright nuclei, each of which contains large, eosinophilic nucleoli . However, they only make up about one percent of the lymphoma, the rest is formed by reactive cell involvement of CD4-positive lymphocytes , monocytes , eosinophilic granulocytes and fibroblasts , which results in a "colorful" cytological picture.

The WHO 's activities into four histological classification types of so-called classical Hodgkin's lymphoma of another form, the lymphozytenprädominanten lymphoma . The classic form is characterized by the immunohistochemically detectable surface features CD30 and partly CD15 . The four different types are in detail:

-

Nodular sclerosing form (60 to 80 percent of cases)

Typical of this most common form of Hodgkin lymphoma are nodular infiltrates and collagen scars. The lacunar cells with a large, lobed nucleus observed in this type are a subspecies of the HRS cells. Young female patients are often affected, especially with mediastinal and supraclavicular involvement. -

Mixed cell form (15 percent of cases)

This is the most common form of Hodgkin lymphoma in patients over 50 years of age, with men more likely than women to be affected. A cervical , but also an abdominal occurrence is typical. Histologically, the picture is colorful with many HRS cells. -

Lymphocyte-rich form (three to four percent of cases)

This form usually occurs as cervical or axillary lymph node involvement and occurs more frequently in male patients around the age of 30. Histologically, B lymphocytes dominate. -

Lymphocyte-poor form (one to two percent of cases)

This rare form is typical of elderly patients and often manifests itself in the abdomen. The cell picture shows few lymphocytes and atypical HRS cells with mitoses.

With today's therapy options, the individual forms of classic Hodgkin lymphoma hardly differ in the #prognosis .

The classic forms are contrasted with lymphocyte-dominant Hodgkin lymphoma (abbreviation: LPHD, former designation: nodular paragranuloma), typically CD30 and CD15 negative, but positive for the B-cell marker CD20. The actual tumor cells of this type are lymphocytic and / or histiocytic cells ( L&H cells ), which can be very similar to the Hodgkin and Sternberg-Reed cells of the classic Hodgkin lymphoma. Popcorn cells , a variation of HRS cells , are a specialty . The clinical course is so good, with only a slight tendency towards metastasis , that in localized stages (IA) radiation therapy without additional chemotherapy is sufficient.

Clinical picture

Hodgkin's lymphoma usually begins with painless lymph node swellings that are baked into packages, which are present in 80 to 90 percent of patients at the time of diagnosis. They occur mainly on the neck (cervical), under the armpit (axillary) or in the groin region (inguinal), but also in the middle layer of the chest ( mediastinal ) and (in abdominal lymphogranulomatosis) in the abdomen ( abdominal ).

This is accompanied by unspecific general symptoms, the so-called B symptoms. This is understood to mean fever (occasionally as wave-shaped Pel-Ebstein fever ), night sweats and a (not otherwise explainable) weight loss of more than ten percent within six months. Reduced performance and itching can also exist. The swollen lymph nodes are rarely painful after alcohol consumption, but this so-called alcohol pain is almost pathognomonic for Hodgkin's lymphoma. In some cases, an enlarged liver ( hepatomegaly ) or spleen ( splenomegaly ) can be observed.

In advanced stages with organ involvement , disturbances of the nervous system , the hormonal balance , the urogenital tract as well as complaints of skeletal and lung involvement can occur. A weakening of the immune system and, as a result, increased infections , especially tuberculosis , fungal and viral infections , are possible.

Hodgkin's lymphoma can also appear as a result of paraneoplastic syndromes . This is understood to mean diseases or symptom complexes, which are mostly caused by autoimmune mechanisms, which in turn can be traced back to Hodgkin's disease, which has not yet been diagnosed. Possible paraneoplastic syndromes are skin diseases such as acquired ichtyosis and pemphigus or diseases of the nervous system such as autonomic, motor and sensory neuropathies (nerve damage), encephalitis (inflammation of the brain) or the so-called ophelia syndrome. consisting of hippocampal sclerosis and dementia . Autoimmune diseases of the eyes such as inflammation of the dermis ( scleritis ) also occur in this context. The paraneoplastic syndromes often occur before the first illness or relapse.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis

The suspected diagnosis is based on the clinical picture, which is captured by anamnesis and examination . Laboratory values also provide information: The rate of sedimentation and C-reactive protein (CRP) are often increased as signs of inflammation . Absolute lymphopenia (lack of lymphocytes, a type of white blood cell) (up to <1000 / µl) is typical , and eosinophilia is found in one third of cases . The laboratory may also show anemia (lack of red blood cells), thrombopenia (lack of blood platelets) and an increase in LDH . A lowered iron value and an increased ferritin are more or less unspecific .

The diagnosis is confirmed by the histological examination of biopsies or completely removed suspicious lymph nodes.

Staging exams

The aim of the following clinical staging (clinical staging) is all manifestations to capture and determine the spread of the disease. This is done on the basis of the findings from the anamnesis, examination, laboratory values, biopsies of the bone marrow with fine tissue assessment and imaging procedures. These include X-ray images of the thorax in two planes, thoracic computed tomography (CT), sonography (ultrasound), and CT of the abdomen and a bone marrow biopsy . Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can also be used instead of CT in certain patient groups with Hodgkin's disease . The positron emission tomography (PET) is then used in the staging of Hodgkin's disease are increasingly in addition to CT or MRI if the other aforementioned imaging techniques do not provide adequate safeguards information about a decline of the disease under treatment. The aim of the PET examinations should be to control the therapy even better according to the disease activity.

The method of pathological staging with laparotomy (open abdominal surgery) and splenectomy (removal of the spleen) is now out of date and is no longer performed.

Staging

On the basis of the findings of clinical staging, but regardless of the histological type, Hodgkin's lymphoma is divided into four stages according to the Ann-Arbor classification (with modifications by the Cotswolds Conference 1989):

| Stage I. | Involvement of a single lymph node region (I N ) or a single localized extranodal focus (I E ) |

| Stage II | Involvement of two or more lymph node regions on one side of the diaphragm (II N ) or localized extranodal foci and involvement of one or more lymph node regions on one side of the diaphragm (II E ) |

| Stage III | Involvement of two or more lymph node regions on both sides of the diaphragm (III N ) or localized extranodal foci on both sides of the diaphragm (III E ) |

| Stage IV | Widespread ( disseminated ) involvement of one or more extralymphatic organs with or without involvement of lymph nodes |

Accessories:

A - without B symptoms

B - with B-symptoms

E - extranodal involvement (outside lymph nodes)

(Milzbefall - S S Pleen; English for spleen)

X - larger tumor mass ( bulk or bulky disease : tumor> 10 cm maximum diameter in adults)

In children and adolescents, an attack on the bone with destruction of the substance ( compacta ) or an attack on the bone marrow is always considered stage IV, regardless of the size or number of the affected lymph node stations.

therapy

The therapy of Hodgkin's lymphoma is based on chemotherapy and radiation . Therapy is adapted to the stage of the disease, with the Ann Arbor stage and existing risk factors being divided into three groups: limited stages , intermediate stages, and advanced stages (see table). Before starting chemotherapy, it should be ensured that measures have been taken to ensure the patient's fertility (for example freezing sperm).

Therapy studies

The German Hodgkin Study Group (GHSG) has been researching treatment options for Hodgkin lymphoma since 1978. Since then, over 14,000 patients have participated in the therapy studies, in which 400 centers are involved. Currently (2014) the sixth generation of studies with the studies HD16 (limited stages) and HD18 (advanced stages) as well as the study HD17 (intermediate stages) is current. Through such studies, among other things, the significant improvement in prognosis over the past 20 years has been achieved; the aim of the current studies is above all to reduce the side effects of the therapy. Based on these studies, the GHSG publishes recommendations for the therapy of the various stages, which consists of chemotherapy in combination with radiation therapy.

| group | Stage / risk factors | Standard therapy |

|---|---|---|

| limited stages limited disease |

Stages I and II without risk factors | Study: HD16

or Chemotherapy: 2 × ABVD + radiotherapy: 20 Gy involved field |

| intermediate stages intermediate disease |

Stages I and II with risk factors (≥ 3 lymph node areas, high ESR) Stages I-IIA also with large mediastinal tumor (bulk tumor) or extranodal involvement | Study HD17

or Chemotherapy: 2 × BEACOPP escalated + 2 × ABVD + radiotherapy: 30 Gy involved field |

| advanced stages advanced disease |

Stages IIB with bulk tumor, III and IV | Study HD18 (18-60 years old)

or Chemotherapy: 6 × BEACOPP escalated + radiotherapy: 30 Gy involved field of PET-positive residual tissue ≥ 2.5 cm or in patients> 60 years: 6.8 × ABVD + radiotherapy: 30 Gy involved field of PET-positive residual tissue> 1.5 cm |

The following are considered risk factors:

- large mediastinal tumor (more than a third of the chest diameter)

- Tumor growth outside of lymph nodes

- high sedimentation rate

- Involvement of more than two lymph node areas

In Germany, the diagnosis, treatment and follow-up care (follow-up) of Hodgkin's lymphoma in children and adolescents is supported by the multicenter therapy optimization study HD-2003 of the Society for Pediatric Oncology and Hematology (GPOH) and the German Working Group for Leukemia Research and Treatment in Children (DAL ) carried out. All pediatric oncology centers in Germany treat according to this study. Attached to the HD-2003 study are therapy optimization studies for the treatment of recurrences of Hodgkin lymphoma or for the treatment of Hodgkin lymphoma in certain risk groups (congenital or acquired immune defects ). The treatment of children and adolescents with Hodgkin lymphoma in therapy optimization studies has been carried out since 1978 (DAL-HD 78 study). In other countries the treatment is similar [in the USA, for example, according to the therapy optimization studies by the Children's Oncology Group (COG)].

In the case of children, special features must be taken into account during therapy. On the one hand, in the majority of patients, growth is not complete. This leads to special problems in radiotherapy, especially in the case of extensive infestation and thus an extensive radiation field, since radiotherapy itself increases the risk of radiation , i.e. H. later promoted new cancers. On the other hand, certain cytostatics have a toxic effect on sperm formation . Other negative growth-related effects on internal organs also require adapted therapy plans. As an essential distinction to adults, the treatment plan is also geared towards gender.

| group | stage | gender | chemotherapy | Radiotherapy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| limited stages limited disease |

IA, IB IIA |

girl | 2 × OPPA (week 1-8) | if no complete remission after chemotherapy: involved field radiotherapy (IF-RT) |

| Boys | 2 × OEPA (week 1-8) | if no complete remission after chemotherapy: involved field radiotherapy (IF-RT) |

||

| intermediate stages intermediate disease |

I E A, I E B II E A, IIB IIIA |

girl | 2 × OPPA (week 1-8) + 2 × COPDIC (week 9-16) or + 2 × COPP (week 9-16) |

involved field radiotherapy (IF-RT) |

| Boys | 2 × OEPA (weeks 1-8) + 2 × COPDIC (weeks 9-16) or + 2 × COPP (weeks 9-16) |

involved field radiotherapy (IF-RT) | ||

| advanced stages advanced disease |

II E B III E A, III E B, IIIB IV |

girl | 2 × OPPA (week 1-8) + 4 × COPDIC (week 9-25) or + 4 × COPP (week 9-25) |

involved field radiotherapy (IF-RT) |

| Boys | 2 × OEPA (week 1-8) + 4 × COPDIC (week 9-25) or + 4 × COPP (week 9-25) |

involved field radiotherapy (IF-RT) |

chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is carried out as poly or combination chemotherapy. According to Hudson and Donaldson, this should have the following properties:

- Every cytostatic (drug) used should have an anti-tumor activity (antineoplastic) effect.

- The cytostatics (drugs) used should differ in terms of their mechanism of action in order to have different points of attack against the tumor and to delay the development of resistance.

- The toxicities of the individual cytostatics should ideally not overlap. At least the toxicities of the cytostatic agents should be such that each individual cytostatic agent can be used in its full individual dose.

Various cytostatics are combined according to these principles. In international therapy protocols, the cytostatics are administered in fixed doses and cycles. Different protocols and different numbers of cycle repetitions are used depending on the progression of the disease. The schemes of choice are the ABVD protocol and the BEACOPP protocol.

In Germany, in accordance with the therapy recommendations of the German Hodgkin Study Group, ABVD is used in limited (two cycles) and intermediate stages (four cycles), BEACOPP in advanced stages with eight cycles in an increased (escalated) dose. The reason for this is that the likelihood of recurrence is slightly lower with BEACOPP, although there are somewhat more long-term effects compared to ABVD. In contrast, in the United States, ABVD is the standard of care for all stages, but BEACOPP is also used as an alternative.

Chemotherapy in children and adolescents corresponds in its basics to chemotherapy in adults: block or cycle poly-chemotherapy is also carried out in children. In Germany, the following combinations are used in the primary treatment of Hodgkin's disease:

- OEPA (or VEPA): vincristine ( O ncovin), E toposid , P rednison , A driamycin

- OPPA (or VPPA): vincristine ( O ncovin), P rocarbazin , P rednison , A driamycin

- COPDIC: C yclosphosphamid , vincristine ( O ncovin), P rednison , D acarbazin

- COPP : as in adults.

In contrast to adulthood, sex partly determines the combination chemotherapies used in chemotherapy in childhood: due to its toxicity on sperm formation, the procarbazine was removed from the OPPA block and replaced by etoposide: this is how the original OPPA block results in the OEPA- Block. The latter are given to boys, the former to girls, whose ovaries are significantly less sensitive to procarbazine than the boys' testicles .

Chemoimmunoconjugate

An antibody-drug conjugate (ADC) for the treatment of CD30 + Hodgkin's lymphoma has been available in the European Union since the end of 2012 with the substance brentuximab vedotin . The medicinal product is approved for the treatment of adult patients with relapsed or refractory CD30 + Hodgkin's lymphoma after autologous stem cell transplantation or after at least two previous therapies, if autologous stem cell transplantation or combination chemotherapy is not an option.

An immunophenotypic characteristic of classical Hodgkin lymphoma is the CD30 molecule . Brentuximab Vedotin links an anti-CD30 antibody to the cytostatic drug monomethyl auristatin E (MMAE) via an amino acid linker. The antibody-drug conjugate was investigated in previously treated and refractory Hodgkin and other CD30-positive lymphoma patients.

Monoclonal antibodies

Treatment with nivolumab can also be considered for HL. The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of nivolumab on overall survival, quality of life, progression-free survival, response rate, grade 3 or 4 adverse events, and major adverse events.

radiotherapy

| Irradiation fields in involved-field irradiation of Hodgkin's lymphoma | |

|---|---|

| Infestation | Irradiation fields |

|

Stage II involvement of the cervical lymph nodes on the right and the lymph nodes in the upper mediastinum |

|

|

Stage III as above, plus: lymph node involvement on the left side of the neck and lymph node involvement under the diaphragm |

|

| Yellow: areas affected by Hodgkin's lymphoma Red: radiation fields Blue: diaphragm |

|

In the case of nodular paragranuloma ( NLPHL ), radiation alone is also used without chemotherapy. The irradiation (radiotherapy) is carried out using the involved-field technique, which means irradiation of every clinically manifest infestation while leaving out the adjacent region. The recommended total dose is 20 or 30 Gray (Gy) depending on the stage , which is divided into individual doses of around 2 Gy per day of treatment. Consolidating radiation of selected tumor locations - such as bulk regions or residual tumors - is also possible after chemotherapy . In the HD16 and HD17 studies, irradiation after chemotherapy is dispensed with in the case of negative PET in order to reduce the late toxicity of the treatment.

Radiation therapy is also used in children and adolescents. Basically, it follows the same principles as radiation therapy for adults. All regions that were affected at the time of diagnosis are irradiated (for the risk groups intermediate and high or intermediate disease and extended disease ). This means that the initially affected region is irradiated, even if the infection has completely receded under chemotherapy. The irradiation is also carried out using the involved-field technique: the affected area is irradiated with a safety distance of 2 to 3 cm. The total dose (cumulative dose) used in children and adolescents is 20–30 Gy, the division (fractionation) is administered with individual doses of 2 Gy per day.

Due to the mostly still progressive growth in childhood, the irradiation of larger regions with the involved-field technique is not without problems in the case of extensive infestation (stage III or IV according to Ann Arbor ). If lymph node regions above and below the diaphragm are affected by Hodgkin's lymphoma, the total radiation fields are large despite the limitation of the radiation fields using the involved-field technique. These often contain structures that are particularly important for growth, such as the spine or thyroid gland .

In addition, the connection between radiation therapy for Hodgkin lymphoma and the development of secondary malignancies (second cancer) is well described and has now been established. The frequency or probability of secondary malignancies occurring depends on the one hand on the dose used and on the other hand on the radiation field and its size. Consequently, the aim of further therapy developments is to reduce radiation to the absolute minimum. A dose reduction below 20 Gy total dose does not make sense, since such a dose limits the effectiveness of the radiation against Hodgkin lymphoma. One approach pursues the reduction of the radiation fields. On the one hand, the need for radiation can be reduced through intensification or new chemotherapies. On the other hand, affected regions that have regressed completely under chemotherapy can be excluded from radiation. In order not to reduce the therapeutic effectiveness of the overall treatment as much as possible, examination methods such as PET are used to determine the need for radiation.

Vitamin D

A vitamin D deficiency worsens the prognosis of patients with Hodgkin's lymphoma.

Supportive therapy

Standard therapy can be supported by supportive therapy that, for example, supports the patient's well-being. One option for supportive therapy could be exercise . The evidence turned out to be very uncertain about the effect of exercise on anxiety and serious adverse events. Exercise may cause little or no change in mortality, quality of life and physical function.

Therapy success control (restaging)

In order to check the therapeutic success of chemotherapy and radiation therapy, new diagnostics (staging) are carried out at regular, predetermined time intervals. These examinations are collectively referred to as restaging (re-grading). The same examination procedures are used for restaging as for staging during the initial diagnosis. The results of restaging are compared with the results of staging. This is used to determine the response to therapy and the extent of the response. Depending on the therapy protocol used or the therapy optimization study, restaging examinations are planned after two, four or six chemotherapy cycles as well as before and after radiation therapy.

One way of monitoring the success of the therapy can be positron emission tomography (PET), for example after the second chemotherapy cycle. When comparing PET-negative (= good prognosis) and PET-positive (= bad prognosis) patients, Aldin et al. the following results: The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of negative and positive interim PET studies on progression-free survival. Negative interim PET exams may result in an increase in progression-free survival compared to positive exam results when the adjusted effect is measured. Negative interim PET results can lead to a marked increase in overall survival compared to positive results. This also applies when the adjusted effect is measured.

Aftercare

After the end of therapy / remission , follow-up usually takes place every three months in the first year, every six months from the second year and annually from the fifth year.

Follow-up care essentially consists of sonography of the previously affected area and a blood test. An X-ray of the thorax or a computed tomography is also taken at longer intervals .

Relapse therapy

If a relapse occurs after more than twelve months in complete remission, another chemotherapy is carried out with a good chance of long-term remission. If the phase of complete remission is shorter or if the remission is incomplete (primary therapy failure), intensified polychemotherapy ( salvage therapy ) can be attempted. Alternatively, myeloablative (bone marrow-optimizing) high-dose chemotherapy is carried out with subsequent bone marrow or stem cell transplantation ; the latter can also be carried out autologously (through self-donation during complete remission). The alternative is an allogeneic blood stem cell transplant , where the donor of the blood stem cells is not the patient, but someone else (related or unrelated). This method is currently to be classified as experimental and is being tested internationally in studies. So far, however, a benefit has not been proven. The same applies to stem cell transplants with reduced-dose or reduced-intensity conditioning treatment using chemotherapy or radiation therapy (non-myeloablative stem cell transplantation; mini-transplant ).

A chemoimmunoconjugate ( brentuximab vedotin ) for the treatment of relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma has been approved in the European Union since the end of 2012 .

Treatment of side effects

In addition to the well-known side effects of chemotherapy such as hair loss and nausea, chemotherapy or a stem cell transplant can also lead to bleeding. It was found that platelet transfusions for chemotherapy or stem cell transplant patients had different effects on the number of patients with a bleeding event, the number of days with a bleeding event, mortality from a bleeding, and the number of platelet transfusions, depending on which Form they have been used (therapeutically, depending on a threshold, with different dosages or prophylactic).

In 2015, the use of prophylactic platelet transfusions to prevent bleeding was evaluated. Prophylactic platelet transfusions for chemotherapy or stem cell transplant patients at a threshold of 10,000 may cause little or no change in the number of days with a significant bleeding event per patient, the number of participants with grade 3 or 4 bleeding, and time until the first episode of bleeding. Prophylactic platelet transfusions may cause a small reduction in the number of transfusions required. These transfusions may cause only a small increase in the number of patients with bleeding. Prophylactic platelet transfusions at a threshold of 10,000 can greatly increase mortality for all reasons.

forecast

Survival rates have increased significantly over the past few decades. Thanks to the stage-adapted therapy, the prognosis is now also good for advanced stages. The evaluation of the third generation of studies by the GHSG showed a five-year survival rate of over 90 percent, also for the intermediate stages (HD8 study) and advanced stages (HD9 study), which is supported by the interim results of the fourth study generation.

Treatment outcomes for Hodgkin's lymphoma relapse or recurrence largely depend on the time between completing the first treatment and when the relapse occurs. If the relapse occurs within three to twelve months after the end of the initial treatment, the prognosis of the relapse with subsequent therapy is worse than with a relapse that occurs more than twelve months after the end of the initial treatment. In addition to the time of the relapse, the extent and side effects of the relapse itself are also of prognostic importance. A relapse with extension corresponding to stage III or IV according to Ann Arbor, a hemoglobin value of less than 10.5 g / dl in women and less than 12.0 g / dl in men are unfavorable. According to data from the German Hodgkin Study Group (GHSG; Internal Oncology), these three criteria or factors essentially determine the prognosis. Patients who do not meet any of the three criteria have a recurrence-free four-year survival rate of 48 percent. Patients who meet all three criteria have a recurrence-free four-year survival rate of 17 percent.

Patients who

- do not come into complete remission (complete disappearance of the disease) during or after the initial treatment of your Hodgkin lymphoma or

- experience a progression of the disease during ongoing therapy or

- suffer a relapse within three months of the end of the initial treatment,

also have a bad prognosis. According to the GHSG data, the recurrence-free five-year survival rate in these patients is 17 percent. If high-dose chemotherapy is carried out, the recurrence-free five-year survival rate increases to 42 percent. However, only 33 percent of the patients with the aforementioned criteria receive high-dose chemotherapy, as Hodgkin's lymphoma progresses rapidly in the remaining 67 percent or high-dose chemotherapy is associated with an extremely high risk of side effects. Patients are also often in an insufficient general condition for a planned high-dose chemotherapy.

In children and adolescents, the prognosis in developed countries is excellent thanks to the use of multimodal therapy optimization studies. In Germany, 96 percent of all 920 cases survived for five years between 1994 and 2003, ten years after diagnosis, 95 percent of the 920 cases were still alive.

The good prognosis after the initial therapy is somewhat clouded by the long-term toxicity of radio / chemotherapy:

damage to the heart muscle (from adriamycin and radiation) and the lungs (from bleomycin and radiation), thyroid dysfunction and fertility disorders are observed, among other things. The most important late complication, however, is the secondary development of other forms of cancer, in particular breast cancer , thyroid cancer or acute myeloid leukemia . The incidence of such secondary neoplasms is around 15–20 percent in 20 years.

Historical aspects

Hodgkin's disease was not the first cancer to be discovered, but it was one of the first for which effective therapies were developed. Repeated improvements in therapy and their clinical verification in studies have led to today's therapeutic successes in the initially incurable Hodgkin's disease.

In 1666 Marcello Malpighi was one of the first to describe probably a Hodgkin lymphoma in his work De viscerum structura exercitatio anatomica .

The disease was named after Thomas Hodgkin , who in January 1832 described various cases of a disease affecting the lymphatic system in his work On the morbid appearances of the Adsorbent Glands and Spleen .

Langhans and Greenfield first published papers on histopathological aspects of the disease in 1872 and 1878, but the Sternberg-Reed cells were not described independently until 1898 by Carl Sternberg and in 1902 by Dorothy Reed . Named after Sternberg, Hodgkin's lymphoma was also named Sternberg's disease .

Krumbhaar and Krumbhaar first observed in 1919 that mustard gas poisoning is associated with leukopenia . In 1931, Adair and co-workers carried out the first experimental investigations into the use of mustard gas (dichloroethyl sulfide) in cancer. During the Second World War , allied soldiers who were exposed to mustard gas derivatives of the N-Lost group after the sinking of the ammunition transporter SS John Harvey (Bari, December 2, 1943) were exposed to a suppression of bone marrow and lymphatic system, which occurred in the following years has been systematically studied by various researchers such as Goodman (1946). These observations and investigations led to the development of initially mechlorethamine (Mustargen ® ), then cyclophosphamide (1959) and the MOPP therapy scheme based on it (1964), the first combination polychemotherapy for Hodgkin's disease. The first published use of mechlorethamine in the treatment of Hodgkin's disease in children took place in 1952. In the decades that followed, intensive research was carried out on the combination schemes and new therapies were developed, such as MOPP , ABVD , COPP and BEACOPP .

In April 1971, at the conference in Ann Arbor , USA, important definitions for diagnosis and classification ( Ann Arbor classification ) were established. The German Hodgkin Study Group has been researching the effectiveness of various therapies in large, multicenter studies since 1978 and has thus made a significant contribution to the current therapy recommendations and the associated improvement in prognosis.

In 1975, Milstein and Köhler succeeded in producing monoclonal antibodies for the first time , which was honored with the Nobel Prize for Medicine in 1984 as the decisive basis for today's antibody therapies. On this basis, the antibody rituximab was introduced in the 1990s for the treatment of non-Hodgkin lymphomas; in 2002, successful use was also demonstrated in the lymphocyte-predominant form of Hodgkin's disease. A pilot study by Younes et al. for the therapy of classic Hodgkin lymphoma has been running since 2003.

In December 2005, Mathas et al. and Knight, Robertson et al. different molecular mechanisms leading to the development of the disease, which were previously largely unclear and long the subject of intense research.

literature

Textbooks

- P. Calabresi, BA Chabner: Antineoplastic Agents. In: AG Gilman, TW Rall, AS Nies, P. Taylor (Eds.): Goodman and Gilman's the pharmacological basis of therapeutics. 8th, international edition. McGraw-Hill Health Professions Division. New York / St. Louis / San Francisco 1992, ISBN 0-07-112621-X .

- BA Chabner, DL Longo (Eds.): Cancer Chemotherapy and Biotherapy: Principles and Practice. 2nd Edition. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Publishers, Philadelphia / Baltimore / New York 1996, ISBN 0-397-51418-2 .

- V. DeVita, S. Hellman, SA Rosenberg: Cancer. Principles and Practice of Oncology. 6th edition. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Publishers, Philadelphia / Baltimore / New York 2000, ISBN 0-7817-2387-6 .

- FL Greene, DL Page, ID Fleming, A. Fritz, CM Balch: AJCC Cancer Staging Handbook. 6th edition. Springer, New York / Berlin / Heidelberg 2002, ISBN 0-387-95271-3 .

- Markus Sieber, Andrea Staratschek-Jox, Volker Diehl: Hodgkin lymphoma. (PDF) In: Textbook of Clinical Oncology (Springer). v. W. Hiddemann, C. Bartram, H. Huber, archived from the original on December 3, 2008 ; Retrieved August 20, 2009 .

- PA Pizzo, DG Poplack: Principles and Practice of Pediatric Oncology. 4th edition. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Publishers, Philadelphia / Baltimore / New York 2001, ISBN 0-7817-2658-1 .

- RL Souhami, I. Tannock, P. Hohenberger, J.-C. Horiot: Oxford Textbook of Oncology. 2nd Edition. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2002, ISBN 0-19-262926-3 .

Guidelines

- S3- guideline Hodgkin lymphoma, diagnosis, therapy and aftercare of adult patients of the German Society for Hematology and Oncology (DGHO). In: AWMF online (as of 2013)

- S1- Hodgkin lymphoma guideline of the Society for Pediatric Oncology and Hematology (GPOH). In: AWMF online (as of 2007)

Web links

- German Hodgkin Study Group (GHSG)

- Competence network malignant lymphomas

- Detailed information on the historical development of Hodgkin's Research (English)

- Information on Hodgkin's disease in children and adolescents from the Society for Pediatric Oncology and Hematology (GPOH), Germany

- Hodgkin lymphoma. (PDF; 1.36 MB) German Cancer Aid Guide (The Blue Guide 21)

Individual evidence

- ^ Annual report 2004 of the German Childhood Cancer Register (DKKR) of the University of Mainz. (PDF) German Childhood Cancer Registry , archived from the original on September 28, 2007 ; Retrieved March 19, 2011 .

- ↑ a b c d e Herold: Internal Medicine: a lecture-oriented presentation: taking into account the subject catalog for the medical examination: with ICD-10 key in the text and index . Gerd Herold, Cologne 2013, ISBN 978-3-9814660-2-7 .

- ↑ A. Zambelli et al. a .: Hodgkin's disease as unusual presentation of post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder after autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation for malignant glioma. In: BMC Cancer . 2005 Aug 23; 5, p. 109, PMID 16117828

- ↑ S. Caillard et al. a .: Myeloma, Hodgkin disease, and lymphoid leukemia after renal transplantation: characteristics, risk factors and prognosis. In: transplant . 2006 Mar 27; 81 (6), pp. 888-895. PMID 16570013

- ↑ a b S. Mathas u. a .: Intrinsic inhibition of transcription factor E2A by HLH proteins ABF-1 and Id2 mediates reprogramming of neoplastic B cells in Hodgkin lymphoma. In: Nature Immunology . (2006) 7 (2), pp. 207-215, PMID 16369535

- ↑ a b J. S. Knight et al. a .: Epstein-Barr virus latent antigen 3C can mediate the degradation of the retinoblastoma protein through an SCF cellular ubiquitin ligase. In: PNAS . (2005) 102 (51), pp. 18562-18566, PMID 16352731 , PMC 1317900 (free full text)

- ^ Henry H. Balfour Jr .: Progress, prospects, and problems in Epstein-Barr virus vaccine development . In: Current Opinion in Virology . tape 6 , June 2014, ISSN 1879-6257 , p. 1–5 , doi : 10.1016 / j.coviro.2014.02.005 .

- ↑ J. Cossman et al. a .: Reed-Sternberg cell genome expression supports a B-cell lineage. In: Blood . (1999) 94 (2), pp. 411-416, PMID 10397707

- ↑ AC Feiler, H. Herbst, A. Marx Lymphatisches System. In: W. Böcker, H. Denk, Ph. U Heitz, H. Moch (eds.): Pathology. 4th edition. Munich, 2008, pp. 565-567.

- ↑ Competence Network Malignant Lymphomas. Retrieved March 28, 2014 .

- ↑ E. Rizos et al. a .: Acquired icthyosis: a paraneoplastic skin manifestation of Hodgkin's disease. In: The Lancet Oncology . 2002 Dec; 3 (12), p. 727. PMID 12473513

- ↑ W. and M. Tilakaratne Dissanayake: Paraneoplastic pemphigus: a case report and review of literature. In: Oral Diseases . 2005 Sep; 11 (5), pp. 326-329. PMID 16120122

- ↑ BC Oh u. a .: A case of Hodgkin's lymphoma associated with sensory neuropathy. In: J Korean Med Sci. 2004 Feb; 19 (1), pp. 130-133, PMID 14966355

- ↑ S. Kung u. a .: Delirium resulting from paraneoplastic limbic encephalitis caused by Hodgkin's disease. In: Psychosomatics. 2002 Nov-Dec; 43 (6), pp. 498-501. PMID 12444235

- ↑ T. Shinohara et al. a .: Pathology of pure hippocampal sclerosis in a patient with dementia and Hodgkin's disease: the Ophelia syndrome. In: Neuropathology. 2005 Dec; 25 (4), pp. 353-360, PMID 16382785 .

- ↑ MM Thakker et al. a .: Multifocal nodular episcleritis and scleritis with undiagnosed Hodgkin's lymphoma. In: Ophthalmology. 2003 May; 110 (5), S: 1057-1060, PMID 12750114

- ↑ FL Greene et al. a .: AJCC Cancer Staging Handbook. 6th edition. Springer, New York / Berlin / Heidelberg 2002.

- ↑ T. Lister et al. a .: Report of a committee convened to discuss the evaluation and staging of patients with Hodgkin's disease: Cotswolds meeting. In: Journal of Clinical Oncology . 1989; 7, p. 1630.

- ↑ therapy - GHSG - German Hodgkin Study Group. Retrieved March 28, 2014 .

- ^ G. Schellong: Cooperative therapy study HD 78 for Hodgkin's disease in children and adolescents. In: Monthly Children's Health. 1979 Aug; 127 (8), pp. 487-489, PMID 470955

- ↑ a b Summary of the European public assessment report (EPAR) for Adcetris

- ↑ YE Deutsch, T Tadmor, ER Podack, u. a. CD30: an important new target in hematologic malignancies. In: Leukemia & Lymphoma . 2011; 52: 1641-54 PMID 21619423

- ↑ NM Okeley, JB Miyamoto, Zhang X. and a. Intracellular activation of SGN-35, a potent anti-CD30 anti-body-drug conjugate. In: Clinical Cancer Research . 2010; 16, pp. 888-897, PMID 20086002

- ↑ Rothe A, Sasse S, Goergen H u. a. Brentuximab vedotin for relapsed or refractory CD30 + hematologic malignancies: the German Hodgkin Study Group experience. In: Blood. 2012; 120, pp. 1470-1472, PMID 22786877

- ↑ Younes A, Gopal AK, Smith SE, u. a. Results of a Pivotal Phase II Study of Brentuximab Vedotin for Patients With Relapsed or Refractory Hodgkin's Lymphoma. In: Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012; 30, pp. 2183-2189, PMID 22454421

- ↑ B. Pro, R. Advani, P. Brice et al. a .: Brentuximab Vedotin (SGN-35) in Patients With Relapsed or Refractory Systemic Anaplastic Large-Cell Lymphoma: Results of a Phase II Study. In: Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012; 30, pp. 2190-2196, PMID 22614995

- ↑ Marius Goldkuhle, Maria Dimaki, Gerald Gartlehner, Ina Monsef, Philipp Dahm: Nivolumab for adults with Hodgkin's lymphoma (a rapid review using the software RobotReviewer) . In: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews . July 12, 2018, doi : 10.1002 / 14651858.CD012556.pub2 ( wiley.com [accessed July 9, 2020]).

- ↑ Sven Borchmann, Melita Cirillo u. a .: Pretreatment Vitamin D Deficiency Is Associated With Impaired Progression-Free and Overall Survival in Hodgkin Lymphoma. In: Journal of Clinical Oncology , 2019, doi : 10.1200 / JCO.19.00985 .

- ↑ Linus Knips, Nils Bergenthal, Fiona Streckmann, Ina Monsef, Thomas Elter: Aerobic physical exercise for adult patients with haematological malignancies . In: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews . January 31, 2019, doi : 10.1002 / 14651858.CD009075.pub3 ( wiley.com [accessed July 9, 2020]).

- ↑ Angela Aldin, Lisa Umlauff, Lise J Estcourt, Gary Collins, Karel GM Moons: Interim PET results for prognosis in adults with Hodgkin lymphoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prognostic factor studies . In: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews . January 13, 2020, doi : 10.1002 / 14651858.CD012643.pub3 ( wiley.com [accessed July 9, 2020]).

- ↑ N. Schmitz, A. Sureda: The role of allogeneic stem-cell transplantation in Hodgkin's disease. In: Eur J Haematol Suppl. 2005 Jul; (66), pp. 146-149, PMID 16007884

- ↑ Deutsches Ärzteblatt, September 28, 2010: Benefits of allogeneic stem cell transplantation in Hodgkin not proven ( Memento of April 21, 2015 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ I. Alvarez et al. a .: Nonmyeloablative stem cell transplantation is an effective therapy for refractory or relapsed hodgkin lymphoma: results of a spanish prospective cooperative protocol. In: Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation . 2006 Feb; 12 (2), pp. 172-183, PMID 16443515

- ↑ Lise Estcourt, Simon Stan Worth, Carolyn Doree, Sally Hopewell, Michael F Murphy: Prophylactic platelet transfusion for prevention of bleeding in patients with Haematological disorders after chemotherapy and stem cell transplantation . In: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews . May 16, 2012, doi : 10.1002 / 14651858.CD004269.pub3 ( wiley.com [accessed July 9, 2020]).

- ↑ Lise J Estcourt, Simon J Stanworth, Carolyn Doree, Sally Hopewell, Marialena Trivella: Comparison of different platelet count thresholds to guide administration of prophylactic platelet transfusion for preventing bleeding in people with haematological disorders after myelosuppressive chemotherapy or stem cell transplantation . In: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews . November 18, 2015, doi : 10.1002 / 14651858.CD010983.pub2 ( wiley.com [accessed July 9, 2020]).

- ↑ A. Engert et al. a .: Involved-field radiotherapy is equally effective and less toxic compared with extended-field radiotherapy after four cycles of chemotherapy in patients with early-stage unfavorable Hodgkin's lymphoma: results of the HD8 trial of the German Hodgkin's Lymphoma Study Group. In: Journal of Clinical Oncology. (2003) 21 (19), pp. 3601-3608 PMID 12913100

- ^ V. Diehl u. a .: Standard and increased-dose BEACOPP chemotherapy compared with COPP-ABVD for advanced Hodgkin's disease. In: NEJM . (2005) 353 (7), p. 744, PMID 12802024 .

- ↑ R. Kuppers u. a .: Advances in biology, diagnostics, and treatment of Hodgkin's disease. In: Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2006 Jan; 12 (1 Suppl 1), pp. 66-76, PMID 16399588

- ↑ A. Josting et al. a .: A new prognostic score based on treatment outcome of patients with relapsed Hodgkin lymphoma registered in the database of the German Hodgkin Lymphoma Study Group (GHSG). In: Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2002; 20, pp. 221-230, PMID 11773173

- ↑ A. Josting et al. a .: Prognostic factors and treatment outcome in primary progressive Hodgkin's lymphoma - a report from the German Hodgkin's Lymphoma Study Group (GHSG). In: Blood. 2000; 96, pp. 1280-1286, PMID 10942369 .

- ^ Annual report 2004 of the German Childhood Cancer Register, University of Mainz ( Memento from September 28, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Herold, Gerd .: Internal Medicine: a lecture-oriented presentation: taking into account the subject catalog for the medical examination: with ICD 10 key in the text and index . 2016th edition. Herold, Cologne 2016, ISBN 978-3-9814660-5-8 .

- ↑ GM Dores et al. a .: Second malignant neoplasms among long-term survivors of Hodgkin's disease: a population-based evaluation over 25 years. In: Journal of Clinical Oncology. (2002) 20 (16), pp. 3484-3494, PMID 12177110

- ^ T. Hodgkin: On some morbid appearances of the absorbent glands and spleen. (1832) Medico-Chirurgical Transactions, London, 17, pp. 68-114 PMID 4630498

- ↑ C. Sternberg: About a peculiar tuberculosis of the lymphatic apparatus running under the pattern of pseudoleukemia. In: Journal of Medicine. 19 (1898), p. 21.

- ^ DM Reed: On the pathological changes in Hodgkin's disease, with special reference to its relation to tuberculosis. In: Johns Hopkins Hosp Rep. 10 (1902), p. 133.

- ↑ Ludwig Heilmeyer , Herbert Begemann: Blood and blood diseases. In: Ludwig Heilmeyer (ed.): Textbook of internal medicine. Springer-Verlag, Berlin / Göttingen / Heidelberg 1955; 2nd edition ibid. 1961, pp. 376-449, here: pp. 434-437: Die Lymphogranulomatose (malignant granuloma, Sternberg disease, Hodgkin disease).

- ↑ P. Calabresi, BA Chabner: Antineoplastic Agents. In: AG Gilman, TW Rall, AS Nies, P. Taylor (Eds.): Goodman and Gilman's the pharmacological basis of therapeutics. 8th international edition. McGraw-Hill Health Professions Division. New York / St. Louis / San Francisco 1992, ISBN 0-07-112621-X .

- ↑ CPJ Adair, HJ Bagg: Experimental and clinical studies on the treatment of cancer by dichloroethylsulphide (mustard gas). In: Annals of Surgery . 1931; 93, p. 190.

- ^ Janusz Piekałkiewicz : The Battle of Monte Cassino. Twenty peoples are fighting over a mountain. Bechtermünz Verlag, Augsburg, ISBN 3-86047-909-1 , p. 66/67.

- ↑ LS Goodman et al. a .: Use of methyl-bis (beta-chloroethyl) amine hydrochloride for Hodgkin's disease, lymphosarcoma, leukemia. In: JAMA . 1946; 132, p. 126, PMID 6368885

- ↑ VT DeVita Jr u. a .: Combination chemotherapy in the treatment of advanced Hodgkin's disease. In: Annals of Internal Medicine . 1970; 73, p. 881, PMID 5525541

- ↑ M. Medetti: Nitrogen mustards in the treatment of children. In: Osp Maggiore. 1952 Jan; 40 (1), pp. 38-40, PMID 14941617 .