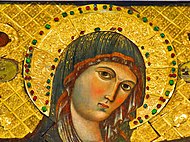

Madonna of Constantinople

The Titles of Mary Madonna of Constantinople Opel , also Holy Mary of Constantinople Opel , ( ital. : Madonna di Costantinopoli , Santa Maria di Costantinopoli ) is usually with the arrival of cult images of Hodegetria brought to the West in connection that the Greek monks ( Calogeri called ) on their flight from Byzantium during the siege of Constantinople (717/18), the iconoclastic persecution (8th – 10th centuries) and after the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople in 1453. It is said that images of virgins were also brought to the West during the Crusades .

Iconographic story

Since the title Madonna of Constantinople is linked to icons of Byzantine origin, the various Madonnas of Constantinople are replicas of the most common oriental iconographic examples. Historically there are no contemporary representations of the Mother of God and soon the search for the archetype began.

The arrival of icons in Italy

There are many legends about the arrival of icons in Italy. A mirror-image copy of the cult image of Mary is said to have been made on canvas in Constantinople, so that the child was on the right arm of the Madonna (Dexiokratusa). Aelia Eudocia would have given this copy to the Western Roman Emperor Valentinian III between 439 and 440 . and his wife Licinia Eudoxia to Ravenna, who personally brought the cult image to Rome, where it would have been kept in the imperial palace complex Domus Augustana on the Palatine Hill . It was later brought to the nearby Chiesa Santa Maria Antiqua at the foot of the Palatine Hill, where the Madonna was copied into one of the frescoes. From here the cult image is said to have been brought to the Chiesa Santa Maria Nova (today: Santa Francesca Romana ). The " Salus populi Romani " is said to have originated from this picture , which is also attributed to Saint Luke and is venerated in the Cappella Paolina in the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore .

The siege of Constantinople by the Muslim Arabs in the years 717/18, the iconoclastic battles in the 8th and 9th centuries, the phenomenon of the Crusades (between 1095/99 and the 13th century) and the capture of Constantinople by the Ottomans in the year 1453 determined the flight of Greek monks (Calogeri) and the importation of cult images (partly in fragments) into the areas of southern Italy. Customs and customs, Byzantine liturgical vestments and architecture also made their influence felt, which were integrated into the historical and popular culture of the south. In various centers in Abruzzo , Molise , Apulia and Campania , the worship of Hodegetria, called in Italy the Madonna of Constantinople, gradually developed.

The Madonna d'Itria

In the legends of the arrival of the icons in the West, literature refers back to two calogeri who, during the second siege of Constantinople in 717/18 by the Muslim Arabs, depict the Madonna Hodegetria with child (also abbreviated to Madonna d'Itria, dell'Itria or dell'Idria) thrown into the sea in a box to bring them to safety. The box is said to be miraculously "stranded" on the coasts of Calabria , Sicily and Sardinia . Sometimes accompanied by two Calogeri and sometimes the box with the Madonna of Calogeri carried on the shoulders is said to have been brought ashore, which is why in the depictions of the Madonna of Constantinople the image of the Virgin and Child who climbs out of a box and often appears carried on the shoulders of two elderly calogeri.

Icon of the Madonna of Constantinople in the Chiesa di San Giovanni Decollato in Nepi

The Madonna d'Itria in the Chiesa Santa Caterina di Valverde in Messina

Madonna d'Itria in the Greco-Byzantine Cathedral of San Demetrio Megalomartire in Piana degli Albanesi

Madonna d'Itria in the Greek-Byzantine Chiesa San Nicolò di Mira, Mezzojuso

Madonna dell'Idria in the Chiesa di Sant'Antonio di Padova in Barcellona Pozzo di Gotto , Messina, 1659

The Madonna of Constantinople in Bari

When the Byzantine Emperor , Leo III. declared the previous cult of images to be "idolatry", he ordered in 730 (in other sources 728) the removal of all "images of Christ, the Mother of God, the saints and martyrs from the churches and the holy places". The walls should possibly be painted over with paint. Many of the cult images are said to have been burned and even more hidden by the Christians in order to return them to the cult after iconoclasm .

When Pope Gregory III. Leo III, who tolerated image worship for educational reasons ("Bible of the Poor"), excommunicated all iconoclasts and thus also the emperor in November 731 at a council in Rome . At the end of January 733, a navy of war in support of the exarch Eutychius from Ravenna to Italy , to attack Rome forcibly, to destroy the images of the saints and to take the Pope prisoner. However, the fleet was shipwrecked .

Thereupon Leo III confiscated. all papal goods in Calabria and Sicily , the removal of all of Sicily and all Balkan countries from the papal jurisdiction and their incorporation into the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople . Gregor then broke off contact with Byzantium .

Legend has it that the Greek monks (Calogeri) of Constantinople, who during the iconoclastic persecution kept the icon of the Madonna Hodegetria painted by Saint Luke, decided to bring it to Rome to meet Pope Gregory III. to be handed over for safekeeping. Two of them embarked in 733 with the help of two sailors from Bari with the precious picture in a box on one of three to Italy from Emperor Leo III. dispatched ships as sailors. At dawn on the first Tuesday in March 733, the only ship in the fleet that had survived a terrible storm landed in the port of Bari.

The sailors from Bari, who had discovered the real contents of the box, forced the Calogeri to leave the Madonna Hodegetria in Bari. In a large procession, in which all citizens took part, the image of the saint was brought to the Chiesa dell'Assunta, today's crypt in the Cathedral of San Sabino in Piazza dell'Odegitria, where today an icon with Riza from a later period as the Madonna of Constantinople is to be considered. Archbishop Bursa ordered the two calogeri, along with two other priests of the local clergy, to watch over the icon day and night and to praise Mary every Tuesday, as was done in Constantinople. The Calogeri stayed until 1158, when the picture was in the care of the cathedral chapter .

Madonna of Montevergine

When Constantinople was sacked and conquered by Franco-Flemish crusaders and Venetians during the Fourth Crusade in 1204 , the patron saint of Constantinople, Hodegetria, was housed as the most valuable relic in the Jesus Pantocrator Church , the Venetian bishopric , where she remained until 1261 Constantinople was retaken from the Byzantines. The then Latin Emperor Baldwin II fled on a Venetian merchant ship . He is said to have taken the head of the great Hodegetria icon with him, which is said to have been brought from Jerusalem to Constantinople by Aelia Eudocia and was considered to be the cult image portrayed by Saint Luke. Owning the Hodegetria was very important at the time. It meant the true palladium of Constantinople and meant securing its protection and the hope of a return to the city that was so close to our hearts.

The icon remained in the family's possession. After Baldwin's death in 1273 or 1274, the icon passed into the possession of his son Philipp von Courtenay and, after his death in December 1283, to that of their only daughter, Catherine de Courtenay (* 1275; † 1307/08), and in 1301 the French Prince Charles von Valois (* 1270; † 1325) married. After the mother's death, the icon went to the daughter Catherine de Valois-Courtenay (1301-1346), last titular empress of Constantinople from the House of Valois-Courtenay, who in 1313 (at the age of twelve) with papal dispensation with the Prince of Taranto , Philip I. , Son of the King of Naples , Charles II of Anjou , was married.

In 1310, Philip and his wife Catherine brought the head of the Hodegetria from Naples to Montevergine and gave it to the Benedictine monks of the pilgrimage site of Montevergine , although this conflicts with the date of their wedding.

With the completion of the body and a border of golden lilies, the royal coat of arms of the Anjou , Philip commissioned the Tuscan painter Montano d'Arezzo , who was commissioned during the lifetime of the Archbishop of Naples , Filippo Capece Minutolo († 1301), the Angevin Decorating family chapel in the cathedral of Naples . In addition, Montano stayed in Naples in 1303 and 1305, where he had been commissioned by King Charles II to decorate the Castel Nuovo in Naples.

A document of the Angevin chancellery dated June 28, 1310 shows that Philip I had commissioned the painter Montano d'Arezzo to work in the family chapel in the cathedral of Naples and the Maestà of Montevergine . In this document Philip describes the painter as a royal “familial” ( see: Art Patronage ) and expresses his appreciation and gratitude towards the artist because they, the Anjou, are mainly devoted to the Madonna. In return for his work, Montana received fiefs.

"[...] maxime in pingendo Cappellam nostram in domo nostra Neapolis quam in ecclesia Beate Marie de Monte Virginis ubi specialem devotione habemus [...]"

"Especially on the painting of our chapel in Naples and the church of Santa Maria del Monte Vergine, which we especially venerate"

The panel is 4.30 × 2.10 × 0.6 m in size , weighs 8 quintals and consists of two large wooden panels that are held together on the back by cross bars. The piece of wood on which the head of the Hodegetria is painted is egg-shaped with a maximum size of 1 m × 85 cm and a gradual thickness from bottom to top of 2 to 5 cm, so that the face of the Madonna has a slight forward inclination .

The Hodegetria became the Madonna of Montevergine. It was given its place in the right nave of the old church, which was converted into a chapel at the request of the Anjou.

Catherine de Valois-Courtenay died suddenly on September 20, 1346 in Naples and was buried in the Chiesa San Domenico Maggiore . At the request of her son Ludwig , her remains were transferred to the Territorial Abbey of Montevergine in September 1347 , where they were buried in the chapel of the Madonna di Montevergine . Ludwig almost promoted a "cult" in memory of the mother. According to the Sinossi della Diocesi di Policastro by Nicola Maria Laudisio, Bishop of Policastro , many churches and chapels in the empire have since been dedicated to the Blessed Virgin Hodegetria , which are commonly called the Madonna of Constantinople because of their Constantinople origin.

"[...] Ex tunc temporis ecclesiae permultae et cappellae ad honorem beatae Virginis Hodegitria (sic) hoc in regno Deo dicatae, vulgo dictae de Costantinopoli ob imaginem ex eo delatam [...]"

Chapel Madonna di Montevergine (on the right you can see the mausoleum of Catherine de Valois-Courtenay and her children Ludwig and Maria)

Chiesa Santa Maria di Costantinopoli in Naples

The forerunner of the worship of the Madonna of Constantinople was the Kingdom of Naples , which found itself in a desperate situation. The plague (1527–1528), siege (1528) and hunger prevailed. The diarist Gregorio Rosso reports that

“[…] L'anno 1528 fu infelicissimo a tutta l'Italia, particolarmente allo nostro Regno di Napoli perché ci furono tre flagelli de Iddio, guerra, peste e fame […]”

"That 1528 was an unhappy year for all of Italy, especially for our [King] Empire of Naples, because there were three scourges of God: war, plague and hunger"

The Neapolitans panicked and organized penitential processions, which the Viceroy of Naples , Philibert de Chalon , forbade and invited the people to meet in the churches and pray there. At the same time, the King of France , Francis I , informed of the difficulties in Naples as a result of the famine, sent the French commander Odet de Foix , Vicomte de Lautrec, to siege the city in Naples. A tactical error in French politics led the Genoese under Filippino Doria (nephew of Andrea Doria ) to separate from their French allies, defer to the Spanish enemy and break the ship blockade on July 4th, while the plague raged among French troops. The survivors of the French army surrendered on September 8, 1528, the day of the birth of Mary .

The people were now freed from the external enemy, but continued to live under the nightmare of the plague, which continued to cause deaths. The epidemic lasted until the beginning of 1529 and continued with greater violence in March. With the summer the "scourge" began to disappear. According to Cesare D'Engenio Caracciolo, Neapolitan historian of the 17th century, 60,000 people died from the plague. Gregorio Rossi attributed both the end of the siege and the end of the plague to the Madonna.

Legend has it that the Virgin appeared to an elderly woman who lived near the city wall, who promised to spare the city from the plague if a church was built in her honor at the place where her picture was found. The "miraculous" picture was found on May 28, 1529 (Tuesday after Pentecost ) on the city wall of Naples. In the same year the Chiesa di Santa Maria di Costantinopoli was built in the street of the same name.![]()

The fresco , painted on marble slab after Byzantine influence, is said to have been painted by a Neapolitan mannerist of the 15th century. The virgin holding the baby Jesus on her right arm is depicted sitting on clouds. John the Baptist and the Apostle John stand by her side. Two kneeling angels hold the clouds that share the heavenly vision of the city of Constantinople on fire. Two little angels pour water onto the flames from two amphorae.

Cesare D'Engenio Caracciolo reports in his “Napoli Sacra” that the Chiesa Santa Maria di Costantinopoli in Naples was not only venerated on the day of its festival, but that all of Naples flocked to it every Tuesday of the year. Some of the devout followers abstained from eating meat and dairy products that day.

“[…] La presente Chiesa è di grandissima divotione […] e non solo il giorno della sua festività, ma anco tutti i martedì dell'anno vi concorre tutta Napoli, e buona parte di quella in cotal giorno s'astiene anco di mangiar carne, e latticini […] La festa principale del titolo della Chiesa con grandissima solennità si celebra nel primo martedì dopo la Pacqua di Pentecoste con straordinario concorso per i molti miracoli […] "

The church became one of the main centers of Marian devotion in the city at that time.

Churches

Chiesa di Santa Maria di Costantinopoli is the name of Italian churches in southern Italy and on the islands of Sardinia and Sicily .

In addition to the four Greek-Byzantine churches in the province of Cosenza :

- Chiesa Santa Maria di Costantinopoli (Castrovillari) in Castrovillari ,

- Chiesa Santa Maria di Costantinopoli (Macchia Albanese) in Macchia Albanese, fraction of San Demetrio Corone

- Chiesa Santa Maria Odigitria (San Basile) in San Basile ,

- Chiesa di Santa Maria di Costantinopoli (Vaccarizzo Albanese) in Vaccarizzo Albanese ,

and one in the province of Palermo :

all churches are Roman Catholic .

See also

literature

- Ingeborg Bauer: Icons of Art: Reflections on the pictorial tradition in East and West . Books on Demand, 2014, ISBN 978-3-7357-2157-0 ( online version (preview) in Google Book Search).

- Gottfried Hierzenberger , Otto Nedomansky: Apparitions and messages of the Mother of God Maria: complete documentation through two millennia . Bechtermünz, Augsburg 1997, ISBN 3-86047-452-9 .

- Gaetano Passarelli: Le icone e le radici. Le icone di Villa Badessa . Fabiani Industria Poligrafica, Sambuceto 2006 (Italian).

- Alfredo Tradigo: Icons and Saints of the Eastern Orthodox Church (Guide to Imagery) . Getty Trust Publications, Los Angeles 2008, ISBN 978-0-89236-845-7 , pp. 163 ff . (English, online version (preview) in the Google book search).

Web links

- Santa Maria di Costantinopoli. Mariadinazareth.it, accessed June 6, 2017 (Italian).

Remarks

- ↑ The term Calogeri (singular: Calogero ; καλόγηρος, Kalògheros) is of Greek origin and is composed of the words καλός (beautiful, good-natured) and γῆρας (old). The name Calogeri was used in eastern and southern Italy for hermit monks of the Basilian order .

Individual evidence

- ↑ calogero. In: Treccani.it. Retrieved July 5, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Lorenzo Ceolin: L'iconografia dell'immagine della madonna . Storia e Letteratura, Rome 2005, ISBN 88-8498-155-7 , p. 113 (Italian, online version (preview) in Google Book search).

- ↑ Gigi Montenegro: Origine del titolo mariano di Madonna di Costantinopoli: il mistero di Montevergine. (PDF) In: Lavesterossa.com. P. 5 , accessed on July 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ a b Origine del titolo mariano di Madonna di Costantinopoli: il mistero di Montevergine , p. 3.

- ^ Restaurata la tela della “Madonna dell'Idria”. 24live.it, accessed June 6, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Herbert Gutschera, Joachim Maier, Jörg Thierfelder: History of the churches: An ecumenical non-fiction book . Herder, Freiburg 2006, ISBN 978-3-451-29188-3 , pp. 100 ( online version in Google Book Search).

- ^ Theodor Dielitz: Geographical-synchronistic overview of world history . Alexander Duncker, Berlin 1846, p. 17 ( online version in Google Book Search).

- ↑ a b c d e Michele Scaringella: La Madonna Odigitria o Maria Santissima di Costantinopoli e San Nicola venerati a Bari. (PDF) p. 6 , accessed on July 25, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Byzantine Empire: Iconoclasm . In: Brockhaus in test and picture . Bibliographisches Institut & FA Brockhaus AG, Mènchen 2006.

- ^ Ferdinand Gregorovius: History of the city of Rome in the Middle Ages. Chapter 81. In: Gutenberg.spiegel.de. Retrieved July 26, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Ferdinand Gregorovius, Chapter 81

- ↑ Gregory III. In: Heiligenlexikon.de. Retrieved July 26, 2017 .

- ^ Walter Ullmann: Brief history of the papacy in the Middle Ages . Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 1978, p. 65 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Bari, cathedral di San Sabino, cripta. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on July 28, 2017 ; Retrieved July 25, 2017 (Italian). Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Margherita Guarducci: La più antica icone di Maria, un prodigioso vincolo tra Oriente e Occidente . Istituto Poligrafico e Zecca Dello Stato, Rome 1989, p. 68 (Italian).

- ↑ PP. Benedettini di Montevergine: Montevergine: guida-cenni storici . Desclée, Lefebvre e C. Editori, Rome 1905, p. 54 (Italian, Textarchiv - Internet Archive ).

- ↑ Matteo Iacuzio, Angelo Maria D'Amato: Brevilogio della cronica ed istoria dell'insigne Santuario di Montevergine real capo della regia Congregazione benedittina de 'Verginiani . Naples 1777, p. 24 (Italian).

- ↑ Brevilogio della cronica ed istoria dell'insigne Santuario Reale di Montevergine, p. 26

- ↑ a b A Mercogliano (AV), presso l'abbazia di Loreto, un convegno dedicato alla "Maestà" di Montevergine di Montano d'Arezzo nei giorni 7 e 8 giugno. Beniculturali.it, accessed June 19, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Gaetano Curzi: Santa Maria del Casale a Brindisi. Arte, politica e culto nel Salento angioino . Gangemi Editore, Rome 2015, ISBN 978-88-492-9829-1 , p. 25 (Italian, online version (preview) in Google Book Search).

- ↑ Matteo Camera: Annali Delle Due Sicilie Dall'Origine E Fondazione Della Monarchia fino a tutto il regno dell'augusto sovrano Carlo III. Borbone, Volume 2 . Fibreno, Naples 1860, p. 163 (Italian, online version in Google Book Search).

- ↑ a b Montano d'Arezzo. Treccani.it, accessed June 18, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Un timbro a secco con l'immagine della Madonna di Montevergine nei documenti d'archivio. Biblioteca Statale di Montevergine, accessed on June 19, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ L'autore della "Maestà" di Montevergine Montano d'Arezzo e la sua rivoluzione. (No longer available online.) Ildomaniditalia.eu, formerly in the original ; Retrieved June 18, 2017 (Italian). ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Madonna di Montevergine. Santiebeati.it, accessed June 19, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Santuario di Montevergine - Mamma Schiavona. Leggenda e tradizione. Avellinomagazine.it, accessed June 19, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Mercogliano, fraz. Montevergine (AV), santuario di Montevergine. (No longer available online.) Nigrasum.it, archived from the original on September 1, 2017 ; Retrieved June 18, 2017 (Italian). Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Gaetano Curzi, p. 117

- ↑ Bishop Nicola Maria Laudisio. Catholic-hierarchy.org, accessed June 20, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Nicola Maria Laudisio: Sinossi della Diocesi di Policastro a cura di Gian Galeazzo Visconti . Edizione di Storia e Letteratura, Rome 1976, ISBN 978-88-6372-017-4 , p. 448 (Italian).

- ↑ La peste del 1528. Solofrastorica.it, accessed on June 22, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Antonio Grumello pavese: Cronaca di Antonio Grumello, pavese: dal 1467 al 1529… Francesco Colombo, Milan 1856, p. 457 (Italian, Textarchiv - Internet Archive ).

- ^ Gregorio Rosso: Historia delle cose di Napoli sotto l'imperio di Carlo V. cominciando dall'anno 1526. per insino all'anno 1537 . Nella stamperia di G. Gravier, Naples 1770, p. 6 (Italian, online version in Google Book Search).

- ↑ a b Cesare D'Engenio Caracciolo: Napoli Sacra . Naples 1624, p. 218 (Italian, online version in Google Book Search).

- ^ Gregorio Rossi, p. 32

- ↑ Nanà Corsicato: Santuari, luoghi di culto, Religosità popolare: il culto mariano nella Napoli d'oggi . Liguori Editore Srl, Naples 2006, ISBN 978-88-207-3973-7 , p. 32 (Italian, online version (preview) in Google Book Search).

- ↑ Cesare D'Engenio Caracciolo, p. 219

- ↑ Cesare D'Engenio Caracciolo, p. 220

- ^ Gregorio Rosso, p. 30