Matter (philosophy)

The term matter is used as a technical term in different epochs, schools, disciplines and discussion contexts of philosophy . In natural philosophy , matter mostly refers to material entities in contrast to immaterial entities such as energy or fields . In the metaphysical history was often for the description of individual objects made between a physical, tactile barrel union substrate and a geometric barrel and integral formation by our knowledge character shape . The Aristotelian thesis that individual objects (so-called primary substances ) each consist of form and matter (so-called hylemorphism ) is particularly important in terms of the history of concepts and the history of ideas .

Another philosophical history in a wide variety of contexts - u. a. metaphysics, philosophy of spirit and ethics - important opposition concerns the separation of the material on the one hand and the spiritual, soul and living on the other. In Descartes' work , "matter" is used to designate the object area of spatially extended objects ( res extensa ) and it is assumed that there is also another object area, the area of the spiritual or mental ( res cogitans ), thus creating a dualism with regard to material and mental Objects is represented. Such theories - in addition to intermediate positions as Emergenzthesen - variants against which only one such object region accept ( monism regarding the material and mental), either only tangible objects existent consider ( materialism ) or only spiritual as existent consider (ontological idealism ) . References to the other object class are then declared in monistic theories either as false or as not referring to fundamental objects. Also philosophically controversial was and is in the case of a dualism with regard to the material and the mental, whether and what type of interaction between both types of objects exists. (See more detailed dualistic answers to the body-soul problem .) If an opposition between the material and the spiritual was also used for practical-philosophical contexts, the orientation towards the latter was usually given a higher priority: the path of the good life leads on from the material to the immaterial-spiritual.

In the course of the development of modern physics , in large parts of natural philosophy, conceptual coining and system experiments related to the development of physical concepts and theories. The more recent systematic natural philosophy, especially in the tradition of so-called analytical philosophy , accordingly largely comprises research questions of the philosophy of physics , which also includes philosophical interpretations of physical statements about the structure of material reality, as well as the interpretation of theoretical terms of physical theories such as " mass " or "matter" itself.

On the concept of matter

The German word "Materie" has its origin in the Latin word "materia" and originally meant "wood, timber". The word matter is etymologically derived from the Latin expressions “mater” (= mother) and “matrix” (= womb) and had the form “materje”, “materge” in Middle High German. In a figurative sense, matter means the object, the topic, the substance of a field of work. The original meaning of “substance from which something is made” has been retained in the German expression material.

Cicero translates the Greek term hyle in the texts of Aristotle with materia . Also hyle originally had the meaning of wood, wood or timber. Aristotle first used the term in a philosophical context and gave it a new meaning. He formed the pair of terms 'form' and 'matter', whereby matter is the basic material on which everything is based, which exists without any properties. Matter is therefore "that from which something arises" (to ex hou). The term “form” describes the internal and external shape and functional structure of an object, while matter addresses the aspect of the object's content. Aristotle replaced the term Chora in Plato, the meaning of which was rather vague.

In addition, Aristotle, whose writings are an essential source for the positions of his predecessors, also used the term hyle for the concepts of the earlier philosophers, although it does not appear in them. It is therefore not clear to what extent he has adequately characterized their positions.

In the common usage of philosophy and physics, the concept of matter is used to denote everything material from which something consists or can arise without reference to anything concrete. Matter also includes the idea of technical design and scientific investigation. It is a counter-term to non-material things such as spirit, ideas, information, force or radiation. As a reflection concept in the context of investigations into reality, the concept of matter stands alongside concepts such as space, time, vacuum, movement, life or energy. In contrast to matter, substances or substances have certain (aggregate) states, so they can be determined through more detailed properties.

For physics, the concept of matter is not a scientific term for which there is a theoretical definition. It does not appear in any mathematical formula in physics. Instead, there has been the concept of mass since Newton , which he called “quantitas materiae”, the quantity of matter. This is a certain property of matter and as such a basic physical quantity. In the sense of this definition, all entities that have a mass can be called matter; however, the use of language is not fixed. Louis de Broglie spoke of “light and matter” (1949), Hermann Weyl and Friedrich Hund of “field and matter”. A widespread combination of words is also that of "matter and energy".

Development of the concept of matter in history

Matter as primary material in early Greek natural philosophy

People measured and weighed materials and substances for a long time before the worldview changed from mythical thinking to a more and more differentiated and deeper rational explanation of the world. In Europe the first documents of this change can be found in the Ionian natural philosophy of the pre-Socratics . Over several generations, these developed speculative theories about what constitutes the basic structures of the world. As in many other cultures at that time, they tried to find a primordial material ( arché ). The first in this series is Thales von Milet (around 624 - around 547), who regarded water as the basic substance of the universe. According to Aristotle, who serves as the main source for Thales, he even assumed that the earth floats on water. The influence of the still existing mythical thinking is shown in the fact that Thales referred to the Greek god of the sea, Okeanos , and his daughter Styx or the border river to the realm of the dead named after her. Similarly, Hippon taught that moisture as such is the basic material because all life needs water. For Anaximenes (approx. 585 - approx. 525), however, everything arises from the air, through compression of water and rock, through dilution, fire. It is the divine and the pneuma as the basis of the invigorating breath and the soul. At Anaximenes, the idea first emerged that matter can transform itself from one substance into another.

Completely different, abstract and primarily not physico-chemical approaches can be found in the following in Anaximander (610 - after 547), Heraklit (around 520 - around 460) and Parmenides (around 520/515 - around 460/455) sought universal world principle. With Anaximander the basis of the world order is the apeiron , which is spatially and temporally unlimited and immeasurable and from which everything material, earth, space and time, arises and into which everything material also disappears again. There is an unlimited number of substances, which in turn consist of similar, infinitely divisible particles of matter. Through a spiritual elementary force, the nous , the judgments are so mixed up that the individual things arise depending on the speed. With this seemingly atomistic approach, he introduces a way of thinking about the world as a process in which opposites influence each other and thus affect the world order as a whole. This thought is even more pronounced in Heraclitus, for whom growth and decay is the basic principle of the world order. In the context of his cosmology , the world fire is the material from which everything arises. The earth itself came into being only later after this world fire. Order and harmony in the world arise from contrasts and changes; "War is the father of all things". Heraclitus called the underlying principle the logos as a universal law of the world. The concept of fire in Heraclitus is often seen as similar to the modern concept of energy. The mathematician Hippasus is also ascribed to having regarded fire as primary material.

For Parmenides, on the other hand, change is an appearance based on a delusion of perception. The principle behind everything is immutable being. A Nothing there is not, because you can only think being, and therefore one is vacuum unthinkable. Space is filled with being everywhere. Only in the world of appearances did Parmenides distinguish between two primary substances, the bright, light, active fire on the one hand and the dark, heavy, suffering matter on the other. Both are mixed by a first mover, the god of love Eros . Melissos defended Parmenides' position that movement could not be, with the argument that there was no space where beings could move because there was no empty space. “And because of that it [being] cannot move either. Because it has nowhere to go, it is full. Because if it were empty, it dodged into emptiness. Since there is now no emptiness, there is no room to evade. "

In a mediation between Heraclitus and Parmenides, Anaxagoras (499-428) developed a doctrine of four basic principles, according to which at the beginning everything was mixed up, that in everything there is a part of everything, that there is no smallest part of anything and that nothing comes out something arises that is not.

atomism

Leukippus (5th century) and his student Democritus (approx. 460 - after 400) are considered to be the founders of atomism . Like Parmenides, they assumed that being as such is unchangeable. In contrast to him, however, they assumed that there is an empty space in which atoms, as the smallest particles, can move freely. This is the only way to explain the diversity and change in phenomena. At the same time Parmenides' ontological thesis of the unity of being was given up. On the other hand, the assumption that motion is associated with a displacement of the atoms relative to one another resulted in the assumption that the atoms themselves are immutable. The atomists maintained the assumption that nothing can come into being. Therefore, for them, the atoms were not created, indivisible (atomos), immutable and immortal. The atoms are all solid and massive, but have different shapes. They can be round and smooth, but also angular and crooked. They also differ in size and arrangement. The perceptible phenomena arise from the fact that the atoms combine in different combinations, so that water, fire, earth, plants or people arise from them. The perceptible qualities of things such as size, hardness, color, but also taste and tones are modes of appearance of the atoms that themselves remain invisible.

With their theory, the atomists have solved a fundamental problem. They could reconcile the thesis of the impossibility of arising and passing away with the experience of change. The changes and movements are caused by pressure and shock. The democritical atomic model thus corresponds to a purely mechanistic worldview . Accordingly, Democritus also understood the soul to be composed of atoms.

After Democritus, atomism faded into the background because the four-element theory of Empedocles (see below) subsequently largely prevailed. Only Epicurus (341-271) took up the theory of the smallest particles again and refined it to include aspects that also became important in the later theory of matter. To explain the movement, he referred to the gravity of the particles, which by nature always fall straight down. The shapes and combinations of the particles were no longer infinite with him. In addition, Epicurus argued that in infinite space there is also an infinite number of worlds. He no longer understood the space merely as a place of connection between the particles, but regarded it as a kind of container. He also developed a theory of the connection of atoms into a kind of molecule . Lucretius (around 95 - around 55) contributed significantly to the dissemination of Epicurean ideas in the Roman Empire , who also presented atomic theory in his didactic poem De rerum natura .

The four elements doctrine

Some important chemical elements such as lead, gold, copper or tin were already well known in antiquity. However, they were not yet viewed as elements in the modern sense , but as special substances. They could not be used to explain the basic principles of the world order. The understanding of matter from the 5th century BC Chr. Until the late Middle Ages rather shaped the doctrine of the four elements of Empedocles (approx. 495 - 435), who gave up the principle of a uniform original material. With earth, water, air and fire as the basic elements, as the roots of all beings, he took up the suggestions of his predecessors and integrated them in a mediating synthesis. With Parmenides, Empedocles also assumed that there is no vacuum and that the universe (Sphairos), which he thought to be spherical, is completely filled with its four primary substances. He also consistently viewed the air as something physical. Likewise, beings cannot perish for him, because otherwise the universe would not be all-encompassing. The drive for the movement are with him the forces of love (attraction) and strife (repulsion). These forces, which can also be thought of as effective causes, are part of a constant cycle process that moves from one pole, the harmony, in transition phases of mixing, to the other pole of complete separation and back through a transition phase.

The centuries-long dominance of the four-element theory , which Plato and Aristotle also took over - each with their modifications - is based, among other things, on the fact that the concept includes the observable aggregate states of matter from solid to liquid to gaseous and this connects with the energy of fire.

Matter and ideas in Plato

With Plato, too, there are various points of reference to his predecessors, whereby a new quality arises through the connection with his theory of ideas . By contrasting the world of ideas, which from his point of view constitute actual reality, with the world of perceived sensory things as appearances, as "shadows of ideas", a dualism between spirit and matter arises, which also gives priority to the spiritual. Plato was the first to include a separation of physical things on the one hand and the structures and principles connected with them on the other in his philosophical concept.

The late Timaeus dialogue is an essential source for Plato's teaching on matter . There the subject of the matter is addressed under three aspects. On the one hand there is the principle of otherness or difference (thateron) in the creation of the world soul (Tim. 35A). Secondly, there is the theory of elements in connection with the concept of the chora , and finally the connection of this theory of elements with an atomistic theory of the smallest particles made up of triangles, which leads to the concept of the Platonic solids . (Tim.47e - 69a).

The explanations of Plato are integrated in a cosmogony in which a demiurge , a creator god , appears as the creator of the world. Plato emphasizes that this creator is a speculation. "To find the Creator and Father of this universe is a difficult task, and to represent him to all, once he has been found, is impossible." (Tim. 28c) The demiurge did not create matter, but in a state of chaotic movement in the dark, incomprehensible, non-empty space, the chora, found. The Demiurge created the order of the world from this original chaos by creating a world body, the visible world, with the four elements fire, earth, air and water. In contrast to the pre-Socratics, these elements are not the original material, but physical expressions of the original material endowed with qualities, which stands for matter, space and energy at the same time. The Chora called Plato the “wet nurse of becoming” (Tim. 49a), who is formless and imperceptible, but comprehensively as a third genus (triton genos) conveys the being as well as the becoming and passing away of the physical world (Tim. 50a-52d ). The elements consist of the smallest particles that have a geometric shape, that of a triangle. Shapes and numbers are the design principles of the elements. The assumption of the smallest particles is reminiscent of the atomists, their well-ordered mathematical form of the Pythagoreans . Equilateral triangles create a tetrahedron as the basic building block of fire, an octahedron as a building block for air and an icosahedron as a building block for water. The earth as the most stable structure of the elements corresponds to the cube as a regular hexahedron that can be constructed from an isosceles right triangle. In this geometric description of the world, the space encompassing everything finally has the shape of a dodecahedron made up of twelve regular pentagons.

The explanation of movement takes place in Plato through the world soul , which was also created by the demiurge. As a mixture, the world soul contains the principles of divisibility and indivisibility of being, identical and different, and mediates between spiritual ideas and the physical world. This changes the elements that can be thought of as a cycle. Earth as the most stable unit, which has its own triangular shape as a basis, is not converted into the other elements. But with the other elements a material change can occur through a compression or dissolution of the connections. Water solidifies into earth and stone or it dissolves into air. As fire divides the other elements including the earth, the air rises and becomes clouds, fog and again water. Substances are derived from the elements. Gold is a form of water because it can be liquefied by fire. Timaeus assumes certain proportions between the elements derived from the geometric symmetries: 1 time water corresponds to 2 times air plus 1 time fire or 5 times fire. Accordingly, once air is twice as fire. The harmony of the elements is expressed in the numerical relationships. Plato's reflections on geometric forms are not taken up again by his successors. The fact that his thoughts as theoretical concepts have a natural scientific interest only becomes apparent in modern disciplines such as crystallography (see for example chrome alum ) or stereochemistry . In some computer games, very small triangles are used as basic shapes for graphics. In particle physics, too, one speaks of symmetries, even if the models there are considerably more complex.

Matter and form in Aristotle

Unlike his predecessors, Aristotle did not approach the subject of matter as a cosmologist, but primarily as an empirical natural scientist. In his physics he posed the question of the relationship between nature as the realm of the changeable and science as the search for unchangeable principles. In analyzing the theories of his predecessors ( Phys. I, 5–9), Aristotle came up with the theses: “There must always be something underlying that which becomes there” (Phys. I, 7, 190a) and “that each The becoming is always a compound ”(Phys. I, 7 190b). From this he concluded: "If there are causes and initial reasons for what is naturally present, [...] then everything arises from the underlying ( hypokeimenon ) and the form (eidos or morphḗ)" (Phys. I, 7, 190b). The basis of all change is matter ( Gen. Corr. I, 4, 320a). Hyle is the causa materialis of all objects in existence. Neither matter nor form emerged as carriers of change, so they have no beginning. “Because with every change something changes and through something and in something. That by which it changes is the first thing that moves; what changes is matter; that in which it changes is the form ”( Met. XII, 3a, 1070a). In change, matter is robbed of a form (steresis, privation ) and receives a new definition . For example, a bronze ball can be converted into a statue. Bronze as matter loses the shape of a sphere and takes on a new shape. The form as such, on the other hand, is not subject to growth and decay (Met. VIII, 3, 1043b).

In Aristotle's work, the concept of matter not only receives a new content, but also a new function. For him, matter becomes an analytical term to describe principles of nature. Every perceivable object, every substance , consists of matter and has a shape ( hylemorphism ). Matter as an abstract expression understood in this way is a relational concept . Matter is dependent and is always the matter of something. It is the space of possibility, the disposition from which an object arises by assuming a certain form. Matter that has become real always has a form. Matter has the passive ability to become something different (Met. VII, 7, 1032a). Here is the connection to the doctrine of act and potency ; for passive, dependent matter without essential properties requires the active form through which an object first receives its essential properties. Matter is the basis for a form to become a concrete individual ( individuation ).

Aristotle's relational character results in a hierarchical structure of matter. The lowest level is the "first matter" ( Materia prima , Hylê protê). This can no longer be traced back to something else, cannot be perceived and is inseparable (Met. IX, 7, 1049a; Gen. corr. II 5, 332a). The first matter is the basis of the four elements from which everything material, all substances, the materia secunda , is composed. Substances arise and perish because they are based on matter. In the hierarchical understanding of matter lies the different perspective on the independence of an object. So a lump of ore can be viewed as an independent object. But he loses his independence when he takes on the function of the matter of a statue (Phys. IV 2, 209b). The divisibility of matter is necessary for there to be individual things at all (Gen. Corr. II 4, 320a).

Aristotle applied the concept of matter not only to material objects, but also to abstract entities , such as mathematical quantities. Matter is the condition of the possibility that one can distinguish unity and multiplicity; “What is many in number has matter” (Met XII 8, 1074a). The concept of matter can also be found with regard to the logic of definition. A term to be defined ( definiendum ) is made up of genre and specific difference. Here the genus of matter and the specific difference correspond to the form of the defining (Met. X, 8, 1058a). In a figurative sense, the body is the matter of the soul ( De an. II, 1, 412a). Shapes are not tied to specific substances. “Because the nature of the form is more decisive than that of the material” (De Part. I 1, 640b). An armchair can consist of different materials. Matter is therefore necessary, but not sufficient for a certain object to arise (Met. VIII 4a and b, 1044a-b). This is due to the fact that it is not the elements that are decisive for the concrete object, but the particular substance that has already been mixed. A certain substance can be unsuitable and imperfect with regard to a certain purpose (Phys. II 8, 199a).

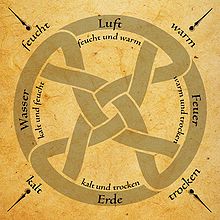

In the concrete development of the concept of matter, Aristotle expanded the four-element doctrine of Empedocles by linking it with the basic qualities of warm and cold as well as damp and dry. So the earth has the combination cold and dry, the water cold and humid, the air humid and warm and finally the fire warm and dry (Gen. Corr. II 3, 330a). The four elements are arranged concentrically in spheres according to their weight, i.e. from bottom to top earth, water, air and luminous sphere, which in turn are enclosed by the celestial sphere ( ether ), which has nothing about itself (Phys. IV 5 , 212b). The ether is also seen as the fifth element ( quintessence ). Because the natural bodies in these spheres strive for a position that corresponds to their weight, this explains the dynamics of physical movements. Like Plato, Aristotle rejected the atomist theory of empty space. a. because there is no resistance in empty space through which movement can be transmitted (Phys. IV 7, 214a-8, 215a). His view that force acts as the cause of maintaining speed was not corrected until the beginning of modern times by Galileo. Likewise, the misconception that heavy bodies fall faster than light ones. From the elements, Aristotle differentiated substances that are equally divided, such as gold, whose substance remains unchanged when it is divided. These fabrics consist of a mixture of the elements that created a new shape. As a further stage of mixing, there are unevenly divided substances that each have a separate function, such as the leaf of a plant. Living beings are made up of equal and unevenly divided materials. The soul is a newly added form (De an. II 1, 412a-412b).

The concept of matter developed by Aristotle has the advantage that it is largely independent of a specific physical theory of matter. With regard to the explanation of movement and change, Aristotle criticized his predecessors for not having developed an acceptable concept for this (Met. XII 6a, 1071b - 10b, 1076a). This also applies to the circular self-movement of matter in the Timaeus. If one thinks the sequence of movements step-by-step and consequently with regard to their causes, one gets lost in an infinite chain (cf. Infinite Regress and Infinite Progress ). Aristotle, on the other hand, posits an immobile mover (Phys. VII 1, 242a-242b), which is without size, without parts, indivisible and imperceptible (Met. XII 7, 1073a). This itself has a divine essence and therefore does not need any matter as the sole exception.

Matter and Pneuma in the Stoa

The Stoa did not use the concept of matter primarily as a principle for individual objects, but as one of two principles for the whole of the world. They imagined the cosmos as an animated organism, in which the process of becoming and passing away is determined by the interaction of the principles of the active effect, the Logos, the world soul, and the passive sufferer, the matter. In contrast to Aristotle, the analytical function of the term is no longer in the foreground, but matter is again viewed as a basic material. It is physically, but qualitatively indeterminate, if it also contains the possibilities of the qualities. In the Stoa, the logos takes the place of the form in Aristotle, but it is not static, but rather dynamic. As a purposeful world soul, it creates order in the cosmos and is realized in man as reason. It acts on the passive matter through the physis, the artistic fire, which through the logos becomes the material πνεῦμα, " Pneuma " (breath, air, breath). The pneuma is presented materially and is a mixture of the active elements fire and air, which are capable of self-movement. The passive elements earth and water change only through the action of the pneumas.

From fire as the most active and first element in which the logos works, the other elements arise through compression. The fire contains germs of diversity, the "logoi spermatikoi", which penetrate the other elements in this process and also create life when the water is created. As with Aristotle, the qualities warm and cold as well as damp and dry play a role in the connection of the elements. Individual substances are created by mixing the infinitely divisible and continuous matter. Mixing was understood by the Stoics not only as the amalgamation of physically or geometrically independent parts, but in such a way that when the parts are mixed together, something qualitatively new is created. The mixing theory also served to explain how metals, e.g. B. gold, can arise.

Against Plato, Zeno von Kition , the founder of the Stoa, argued that action is only possible through physical contact, that the incorporeal, i.e. ideas, can neither work nor suffer. That is why realness can only be predicated of physical things. Only terms that are predicated of something (lekton), that have a meaning ( nominalism ) are incorporeal. God, soul and also qualities, on the other hand, are to be thought of as physical. Because, according to this teaching, only the physical is real, there is no empty space within the cosmos. The cause of the movement is the very fine, warm pneuma, which acts as a tension or attraction between the passive parts of cold matter, matter in the narrower sense. This interplay of mixing and tension is the reason for the creation of the diverse individual things. Depending on the proportion of pneuma, inorganic bodies (hexis), living bodies (physis) or animated objects (psyche) arise. This results in a ladder of beings with an increasing proportion of the logos, of reason.

Emanation of matter in Neoplatonism

Already the Middle Platonist Alcinous had taught a structure of the world from the three original principles God, matter and ideas, whereby he differentiated between the transcendent God and the demiurge as the creator of the world. Against the Stoics he took the view that qualities should be understood as incorporeal and as inherent ( inherent ) ideas in matter .

From here, however, there is no known direct connection to Neoplatonism , the beginnings of which are traced back to Ammonios Sakkas . His pupil Plotinus , who actually gave the ideas of Neoplatonism, tied in with Plato, but intensified his idealism. For him everything that exists arises from the one , the unified and undifferentiated primordial ground. From this one absolute being the whole world unfolds, first the world of the spiritual and only afterwards the material world. This process of emanation is not structured in terms of time or causation. A hierarchy of four levels of being ( hypostases ) in the world emerges , in which the multiplicity of entities expands. From the one, the basis of existence of all things, the spiritual (noetic) world arises, from this again the psychic world and from this finally the perceptible world of secondary matter. The form takes precedence over matter.

The original ground, which has no properties, can only be described by what it is not. The underlying level of the spiritual, the nous , is still transcendent and supra-individual. It is the world of thought, the realm of Plato's ideas. The world of the soul arises from this level. This includes the world soul as a whole as well as the individual souls of living individuals. The soul is the realm of principles and order. The soul has a share (upwards) in the nous, the reasonable and rational thinking, but also in the physical cosmos, of which it is the origin. It is the mediator between the nous and the world of things.

Matter is now subdivided into first matter, which underlies everything, and second matter, which has combined with forms in the physical bodies. Plotinus understood the first matter (“hyle noete”) to be an intelligible principle that already exists on the level of forms and spirit. It is to be clearly distinguished from the second, the sensory matter on the fourth level. For Plotinus and Aristotle, the unformed matter of the noetic world is a pure principle that underlies all objects, without any quality or form. It is imperceptible, indefinite and unknowable. Plotinus transcended Platonic thinking by conceiving matter as the negation of beings. Matter is deprived of all forms of being (privation). Because he identified the one as the perfect with the good, he equated matter with the ontologically bad, because there was no good in it. Only the material matter, the materia secunda, which only exists as formed matter, can be recognized and positive statements can only be made about this. The materia prima, on the other hand, can only be approximately grasped through “false thinking”, in that one thinks away all determinations of being.

| Fire | sharp | fine | movable |

|---|---|---|---|

| air | dull | fine | movable |

| water | dull | rough | movable |

| earth | dull | rough | rigid |

Plotin's pupil Proclus also dealt intensively with the concept of matter and developed a partially different concept. He saw matter as a necessary part of God, not as a result of the creation process, but as eternal. Because the ultimate cause of matter is becoming, because without matter there can be no becoming. In addition to being and becoming, matter is the third genus, which is indispensable for the whole of the world.

With regard to the doctrine of the elements, Proclus created a structural model that deviates from Aristotle, which is supposed to ensure the cohesion of the elements in the cosmos with three pairs of qualities.

Matter Concepts in Early China

The understanding of matter in Chinese philosophy follows a significantly different view than the Western tradition. While in the West the world of things, and with it the structure of matter, is examined with particular interest, in the Chinese schools of thought it is above all the changes and the connections between natural phenomena that are the subject of consideration. There are similarities in the basic principles to the way of thinking of Heraclitus, which up until modern times had hardly found any expression in the theory buildings describing nature in the West. In Eastern thought man wants to be in harmony with the flowing cycles of nature, of which he regards himself as part; In the western world, people want to examine and shape the nature they face as an object in the sense of constant (knowledge) progress.

Taiji is a fundamental term in Chinese philosophy . It is reminiscent of the Greek apeiron, but also of the Neoplatonic one. Taiji as a term became prominent with Zhou Dunyi , the founder of Neo-Confucianism in the 12th century. It is the highest perfection, the original principle of life, which includes all phenomenal aspects of the world, i.e. matter, energy and time. The Taiji arose from the Wuji , the infinite, the highest non-being, the still completely shapeless original state of the universe. The Wuji is empty, without structure, without movement, without time and space, without meaning. Taiji contains a polar structure, the opposites of light and dark, of hard and soft or of warm and cold.

Taiji is the name for the symbol of Yin and Yang known in the West (as a graphic only emerged in modern times), one of the oldest teachings in China, which is already the Yi Jing (traditional German term "I Ching"), the book of changes underlying. Here Yang (the light) is shown as a solid line and Yin (the dark) as a broken, two-part line. These form the basic binary characters for the code of the trigrams and hexagrams in Yi Jing and are the expression of a polar structure that runs through all phenomena in the world. Four different “images” (“The Four Xiàng”) can be put together from the two lines, which correspond in their symbolism to the four-element theory of Empedocles. Air (or sky) and earth are above (old yang) and below (old yin). Fire and water are in between. Fire tends to blaze upwards, which is why it is called "young yang". Water, on the other hand, flows downwards and is called "young yin". The change takes place in an eternal cycle: from old yang (above) to young yin (down), to old yin (down), to young yang (up), back to old yang (up) and so on:

![]() →

→ ![]() →

→ ![]() →

→ ![]() →

→ ![]() →: /:

→: /:

There is also one of the oldest natural philosophical concepts in Asia, the five-element doctrine , which was mainly taught in Daoism and which also represents a similar basic conception of the elements. The elements metal, wood, fire, water and earth differ considerably in their meaning. These are not basic materials, but fundamental dynamic processes that are characterized by the elements based on the properties described therein. Daoism also knows a primordial principle of the cosmos comparable to the apeiron, the Dao.

The origin of all being is the Dao. Dao originally means “way” and in a figurative sense “principle”. Because it is the human ways of describing it deprives itself, called Lǎozǐ in the Tao Te Ching , the first principle Dào, so that the term for the first time the importance of a transcendent received highest reality and truth.

- The SENSE (Dao) creates the one.

- The one creates the two (Yin and Yang).

- The two creates the three (heaven, man and earth).

- The three creates all things.

- All things have the dark behind them

- and strive for the light

- and the flowing force gives them harmony.

A systematic linking of the teaching of Yin and Yang with Wuxing can be found in Zou Yan (approx. 305 - 240 BC). From the concept of the phases of change in nature, a large number of explanations of nature developed, for example in chemical reactions, in medicine for healing processes, but also to describe harmonies in Feng Shui or in the description of correct governance. Everything that happens is a process of becoming and passing away. In the phase of becoming, fire arises from wood, earth (ashes) from fire, metal from the earth and water from this. The same process is found in the seasons. The wood grows in spring, fires arise in hot summer, fruits emerge from the earth in late summer, metal corresponds to autumn and water to winter. On the other hand, there are processes of decay, for example when the roots of the wood penetrate the earth, the water extinguishes the fire, the metal cuts the wood, the fire liquefies the metal or the earth soaks up the water.

The New Confucian Zhang Zai (1020-1077) also combined the teaching of Qi (life energy), which also comes from Daoism and which has similarities with the Pneuma in Greek philosophy, with the teaching of Yin and Yang. The Qi was thought of as a subtle basic substance that dynamically permeates everything that exists and thus acts as energy in all events. Zhu Xi (1130-1200) taught similar things . Yin and Yang are the polarities of Qi, through whose polarities everything arises and passes away. Qi is the energy that a person receives at birth and that he uses up in the course of his life.

Matter Concepts in Early India

In Indian philosophy, various conceptions of matter have developed in the course of history, each of which differs with the ontological basic position. There are the positions of materialism ( Charvaka ), idealism ( Advaita Vedanta ) and also a substance pluralism ( Samkhya , Nyaya , Vaisheshika ).

The first known materialist in India is Ajita Kesakambali , who was around the time of Buddha in the 6th century. v. Lived. He taught that man consists of the four elements earth, water, fire and wind, into which he also dissolves after his death. The four-element teaching can be found in the materialistic school of Lokayata (philosophy of the people) / Charvaka, which advocated a pure sensualism and rejected all forms of the supernatural. Because there is only what is perceptible, this school also rejected the existence of atoms and space. Causality has only material causes just like consciousness, which is an emergent function of the physical brain. The materialists turned against any form of transcendent authority, i.e. against Brahmanism, Buddhism or Jainism, they rejected the teachings of the soul ( Atman ), transmigration of souls ( samsara ), redemption ( Moksha ) and retaliation ( karma ).

According to Vaisheshika, which is based on natural philosophy, nature is divided into six categories ( padarthas ) in the sense of real beings, in substance ( dravya = earth, water, fire, air, ether, space, time, soul, mind), quality ( guna ), activity ( karman ), commonality / generality ( samanya ), difference / particularity ( vishesha ) and inherence ( samavaya ). Everything that exists and the relationships between them should be reflected in these categories. Of the sub-categories of substance, five stand for the material elements earth ( prithivi ), water ( apa ), fire ( teja ), air ( vayu ) and ether ( akasha ), which in turn, with the exception of ether, consist of infinitely small and indivisible , spherical and eternal atoms are composed. The properties of the elements (smell, taste, color / shape, touch, sound) result from the different properties of the respective atoms. The indivisibility of atoms is justified by the fact that otherwise a creation out of nothing ( creatio ex nihilo ) would be possible. Because the atoms are unchangeable and eternal, there is no becoming and passing away, but only mixtures and changes that lead to the forms of the appearances.

In the teaching of Samkhya , what happens in the cosmos is dualistic with the passive, conscious, resting and unifying male spirit ( Purusha ) and the active, unconscious, creative, female "primordial matter" or "nature" ( Prakriti ). Prakriti is the cause of everything, but it has no cause itself, is unconditional and imperishable. Primordial matter is characterized by three essential properties or marks ( gunas ): Tamas (resistance, indolence, darkness, chaos), Rajas (action, restlessness, movement, energy) and Sattva (knowledge, clarity, goodness, harmony). The primordial matter is eternal, but everything is in constant change. All things are composed of atoms that are built up hierarchically. The smallest particles (paramanu) that can no longer be divided can only be recognized in meditation. Seven of them form form atoms ( anu ). These are the finest substance from which fine dust particles (rajas) are formed. Becoming arises through connection, and passing away through the separation of Purusha and Prakriti. Prakriti is in an incessantly flowing movement and the variety of appearances is created by the constant mixing of the Gunas. From these five subtle principles or pure substances (tanmatras) arise, which are converted back into the gross elements ( mahabhuta ) of matter. The ether is the primary element with the principle of sound ( Shabda ), the air is created through movement of the ether with the principle of contact ( Sparsha ), the fire through friction of the air with the principle of shape ( rupa ), the water as compression the air is based on taste ( rasa ) and the coarse element earth, which develops from the coagulation of the water, arises from the Tanmatra smell ( gandha ). The five elements, in turn, are linked to the five passive sense organs of hearing, touch, sight, taste, smell and five organs of action - mouth, hands, feet, sex and anus - for the excretions. Because matter is eternal, the death of a person only means a transformation of the gross body into a subtle structure, which does not affect the immaterial existence of the soul.

In the philosophy of Advaita Vedanta systematized by Shankara , a purely idealistic philosophy is ontologically represented, according to which absolute consciousness ( Brahman ) is the only reality. There is identity between Brahman and the individual soul ( Atman ). Matter, like all other perceptions, is projection (Vikshepa-Shakti), the truth of which is hidden behind the veil (Avriti-Shakti) of the Maya . Matter, movement, energy or thought contents are only thought products, mental constructs, and do not exist out of themselves. In the following, Maya is often thought of as being composed of the three Gunas, comparable to the Prakriti of Samkhya.

Jainism

Jainism , founded by Mahavira , teaches that everything material is animated and is subject to the five categories of movement (dhamma), rest (adhamma), matter (poggala), space (âgãsa) and time ( kala ). The world is uncreated, infinite and eternal. Similar to Buddhism, belief in a transcendent Creator is rejected. The individual soul (jiva) is an immutable, energetic, purely spiritual substance. It is trapped in matter, the inanimate (ajiva), and can be freed from it through ascetic exercises. The atomistically structured matter made up of an infinite number of small, shapeless parts (paramãvu) that can no longer be dismantled and which can combine to form larger units has the properties of color, smell, taste and touch. Since the emergence of Jainism goes back at least to the 6th century BC. BC, this is the oldest doctrine of atomism, which also precedes the Greek atomists.

Buddhism

Also Buddhism knows a theory of elements ( Mahabhuta = the four large elements), which was developed in contrast to the Vaisheshika. There is no ultimate in Buddhism, no Brahman. The elements are not things, but felt properties of a constantly changing, never constant world, which are communicated to the sense organs. The air stands for everything moving, for breathing in and out. The solid, resisting and weighty are connected with the earth. Water is used to describe the property of moisture, flowing, flexible and connecting. Fire is warmth, temperature and energy. Finally, the ether does not correspond to any material properties, but rather stands for emptiness. Among other things , Dharmakirti combined the elements with an atomic theory.

One of the paths to salvation, which is always the goal of Buddhist teaching, is full knowledge of reality. "Rely on yourself and rely on Dharma, the truth" In order to recognize reality, it has to be analyzed in its structures. The starting point is the basic idea that the knower and the known are in constant correlation. The five collections ( skandhas ) are taught as the structure of existence . These are the sensations of the material body ( rūpa ), the feelings ( vedanā ), the perception ( vedanā ), the mental formations ( samskāra ), and finally the consciousness ( vijñāna ). Rupa-Skandha describes the realm of matter, the external basis of all living beings. The other collections are of a mental nature and are only analytically separated, but in reality they are an inseparable unit. Every experience of Rupa is also a mental access to reality. In the realm of matter, the causal relationships of cause and effect apply. For any physical state, the elements are the contributing conditions. But because there is no causal relationship between spirit and matter, spirit must be the basis of all being and matter is only an appearance in spirit. Because the spirit is not perishable and encloses and penetrates everything material.

Matter - Dialectical Materialism

Dialectical materialism is mainly based on the work of Marx and Engels . As a philosopher, Marx was strongly influenced by the work of Hegel and his dialectics . While dialectic historically simply describes the process of speech and contradiction in philosophical discourse, for Hegel this is the development of the concepts themselves, which takes place in internal contradictions. Basically, a concept (thesis) is transformed in a process (negation) into its opposite ( antithesis ). and arises again after a renewed negation on a higher level, in that, however, it now contains this movement in itself without harm ( science of logic ).

However, Marx did not see in this mode of movement the self-movement of the philosophical spirit, but rather the movement of human society in its historical development. For him, it was not different ideas (ideas) about human society that shaped its development, but rather human life itself, especially the contradictions that take place in it. In practice, this is precisely the economy, the study of which he devoted himself to all his life ( Das Kapital ).

This type of application or transformation of Hegel's dialectic by Marx was made the subject of research by many authors themselves. Particularly noteworthy are Engels and Lenin , who both published promptly and directly on this topic ( Anti-Dühring , Dialectics of Nature , Materialism and Empirio-Criticism ). While dialectical materialism deals with the materialistic turn of Hegel's dialectic, historical materialism , which is closely related to it , primarily shows its application to the history of mankind.

In terms of content, the authors distinguish the concept of matter from the concept of spirit and denote the processes that take place outside and independently of the human spirit, which they ultimately give priority to the action of the human spirit. The literature only provides examples of the interplay between the two conceptual components of matter / idea, such as the relationship between base and superstructure .

In this respect, the dialectical concept of matter should not be confused with the physical and rather includes any physical quantity, not just mass, but at the same time does not end with the concepts of physics, but also includes those of economics or law e.g. T. with a. For example, the level of technology that has historically been achieved is understood as material.

20th and 21st centuries

Philosophical interpretations of the concept of matter in the theory of relativity

With the development of the special theory of relativity , Albert Einstein established the well-known formula E = mc² (energy = mass · speed of light²). The convertibility of the properties of mass and energy expressed here reflects physical facts such as the fact that changes in the temperature of a gas affect its inert mass and vice versa, or that electromagnetic radiation (light, heat rays etc.) can be assigned a "dynamic" mass, although the relevant elementary particle (the photon ) has no mass. Different ontological interpretations have been given to this formula : Mass and energy are the same property (Torretti, Eddington ) or two different properties that can either be converted into one another ( Rindler ) or not (Bondi / Spurgin). The difficulty of the ontological treatment of the properties of mass and energy creates ontological problems for the treatment of the “carriers” of these properties: matter and fields.

literature

Overview representations in manuals

- Wolfgang Detel ao: Matter. In: Historical Dictionary of Philosophy , Vol. 5, Schwabe, Basel / Stuttgart 1980, Sp. 870–924.

- Klaus Mainzer : Matter . In: Jürgen Mittelstraß u. a. (Ed.): Encyclopedia Philosophy and Philosophy of Science. Vol. 2, Mannheim a. a. 1984, 796-799

- Christian Tornau : Matter. In: Real Lexicon for Antiquity and Christianity . Volume 24, Hiersemann, Stuttgart 2012, ISBN 978-3-7772-1222-7 , Sp. 346-410

- Stephen E. Toulmin : Matter. In: Donald M. Borchert (Ed.): Encyclopedia of Philosophy , Thomson Gale, Detroit et al. 2005, Vol. 6, ISBN 0-02-865786-1 , pp. 58-64.

Overall presentations and investigations

- Ernst Bloch : The problem of materialism, its history and substance. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt a. M. 1985

- Miguel Espinoza, La matière éternelle et ses harmonies éphémères , L'Harmattan, Paris, 2017, ISBN 978-2-343-13798-8 .

- Eugen Kappler: The change of the concept of matter in the history of physics , in: Yearly publication 1967 of the society for the promotion of the Westphalian Wilhelms-Universität Münster (1967), S. 61-92.

- Joachim Klowski: The emergence of the terms substance and matter. In: Archive for the history of philosophy 48, 1966, pp. 2–42.

- Sigrid G. Köhler, Hania Siebenpfeiffer, Martina Wagner-Egelhaaf (eds.): Materie. Basic texts on the history of theory . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt 2013, ISBN 978-3-518-29651-6

- Marc Lange : An introduction to the philosophy of physics: locality, fields, energy, and mass. Blackwell, Oxford 2002, ISBN 0-631-22501-3 .

- Christoph Lüthy et al. (Ed.): Late Medieval and Early Modern Corpuscular Matter Theory . Brill, Leiden 2001.

- Ernan McMullin (Ed.): The concept of matter in Greek and Medieval philosophy. Notre Dame 1963.

- Ernan McMullin (Ed.): The concept of matter in modern philosophy. Notre Dame 1978.

- Bertrand Russell : The analysis of matter . Routledge, London 1992

- Richard Sorabji : Matter, space and motion: theories in antiquity and their sequel. Cornell University Press, Ithaca 1988, ISBN 0-8014-2194-2 .

- Stephen Toulmin , June Goodfield: The Architecture of Matter , University of Chicago Press, Chicago 1982.

- Norbert Welsch, Jürgen Schwab, Claus Chr. Liebmann: Matter. Earth, water, air and fire . Springer, Berlin / Heidelberg 2013

Web links

- Lexicon entries

- Francis Aveling: Matter . In: Catholic Encyclopedia , Robert Appleton Company, New York 1913.

- Rudolf Eisler : Materie , in: Dictionary of philosophical terms, Berlin 1904.

- Hans-Dieter Mutschler : Matter in the online lexicon Natural Philosophical Basic Concepts , 2012.

- Andreas Preußner: Materie , in: Wulff D. Rehfus (Hrsg.): Concise dictionary philosophy , UTB / Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht 2003.

- Technical articles

- Martin Carrier : On the corpuscular structure of matter in Stahl and Newton , Sudhoffs Archiv, 70 (1/1985)

- Martin Carrier: Passive Matter and Moving Force: Newton's Philosophy of Nature

- Gernot Eder : Metamorphoses of Matter , lecture at the Austrian Academy of Sciences 1998

- Tobias Fox: The substance problem with Schlick and Cassirer. Some aspects of a physically motivated discussion (PDF; 135 kB)

- Josef Honerkamp : Changes in the concept of matter , September 7, 2011

- Harold J. Johnson: Changing conceptions of matter from antiquity to Newton in the Dictionary of the History of Ideas

- Regine Kather : Matter and Spirit - historical and systematic reflections (PDF; 290 kB)

- Fred Jochen Litterst: Atomism and Continuum: A dispute between the pre-Socratics and its consequences , published in: Yearbook 2009 of the Braunschweigische Wissenschaftlichen Gesellschaft, pp. 111–120

- Andrea Reichenberger: On the concept of emptiness in the philosophy of the early atomists , Göttingen Forum for Classical Science 5 (2002), 105–122

- Kizhakeyil Lukose Sebastian : The Development of the Concept of Atoms and Molecules. Dalton and Beyond , Resonance, 15 (2010), 1132-1139

Individual evidence

- ↑ This does not necessarily apply to an epistemological idealism (e.g. Kant ).

- ^ Friedrich Kluge, edited by Elmar Seebold: Etymological Dictionary of the German Language. 24th, revised and expanded edition. de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2001, keyword: "Matter", page 604

- ^ For example Max Jammer : Concepts of Mass in Classical and Modern Physics , Courier Dover Publications, New York 1997, p. 19.

- ↑ Werner Marx : Introduction to Aristotle's Theory of Beings , Freiburg i. Br. 1972, p. 40

- ↑ Aristotle: Physics VII, 3, 245b

- ↑ Wolfgang Detel: Art. Materie, No. 1., in: Historical Dictionary of Philosophy, Vol. 5, Schwabe, Basel / Stuttgart 1980, Sp. 870–880, here 871

- ↑ Manfred Stöckler: Materie, in: Handbuch philosophischer Grundbegriffe, Volume 2, ed. By Petra Kolmer and Armin G. Wildfeuer, Alber, Freiburg 2011, 1502-1514, here 1502

- ↑ Hermann Weyl: Field and Matter, Annalen der Physik. 4th episode. Volume 65 (1921); Friedrich Hund: Matter and Field, Springer, Berlin 1954

- ^ Aristotle: De Caelo, B19, 234a

- ↑ Diels / Kranz 22B53

- ^ Klaus Mainzer: Matter. From primordial matter to life, Beck, Munich 1996, 12

- ↑ Aristotle, Metaphysics 984a7

- ↑ The Fragments of the Pre-Socratics. Greek and German by Hermann Diels, Volume 1, 2nd edition 1906, 146

- ^ Christof Rapp: pre-Socratics. Beck, Munich 1997, 194

- ↑ Wolfgang Röd: The philosophy of antiquity 1. From Thales to Demokrit, 3rd edition Beck, Munich 2009, 196

- ↑ Heinz Happ : Hyle. Studies on the Aristotelian concept of matter, 96-97

- ↑ Matthias Rugel: Matter Causality Experience. Analytical Metaphysics of Panpsychism, Mentis, Paderborn 2013, 110

- ↑ Max Pohlenz: The Stoa: History of a Spiritual Movement, 1984, 79

- ↑ Cf. Dudley Shapere: Matter , in: Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy , § 1.

- ↑ Max Pohlenz: The Stoa: History of a Spiritual Movement, 1984, 64

- ↑ Christoph Helmig: The breathing form in matter. Some reflections on the “enylon eidos” in the philosophy of Proklos, in: Mathias Perkams, Rosa Maria Piccione (ed.): Proklos. Method, Sehlenlehre Metaphysik, Brill, Leiden 2006, 259-278, here 262

- ↑ Wolfgang Detel: Art. Materie, Part I, in: Historical Dictionary of Philosophy, Vol. 5, Schwabe, Basel / Stuttgart 1980, Sp. 870–880, here 880.

- ↑ Evangelia Varessis: Die Andersheit in Plotin, de Gruyter, Berlin 1996, 289

- ↑ Benjamin Gleede: Plato and Aristoteles in der Kosmologie des Proklos, Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2009, 335ff

- ↑ Proklos: Commentary on Plato's Timaeus (In Tim.III, 150c-152a, Bd. 2, 36.30-42.2 Diehl) Information and explanation from: Mischa von Perger: Die Allseele in Plato's Timaeus, de Gruyter, Berlin 1997 , 75-76

- ^ Joseph Needham : Science and Civilization in China, Volume 2 (History of Scientific Thought), Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1956, 243-244

- ↑ Daodejing, 42, translation by Richard Wilhelm, brackets added for explanation

- ↑ Norbert Welsch, Jürgen Schwab, Claus Chr. Liebmann: Materie. Earth, water, air and fire. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg 2013, 47-49

- ^ Paul Schweizer: Indian Concept of Matter. In: Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Volume 10, edited by Edward Craig, Taylor & Francis, 1998, pp. 197-200

- ↑ Debiprasad Chattopadhyaya : Indian Philosophy. 7th ed. People's Publishing House, New Delhi, 1993, p. 194

- ↑ Abigail Turner Lauck Wernicki: Lokayata / Carvaka-Indian Materialism. In: Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy .

- ↑ Amita Chatterjee: Naturalism in Classical Indian Philosophy. In: Edward N. Zalta (Ed.): Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy .

- ↑ Andreas Binder (translation and commentary): A dvaita Vedanta - Awakening to Reality: An Introduction by Sri Shankaracharya's Tattva-Bodha and Atma-Bodha. Books on Demand, Norderstedt 2008, p. 106

- ↑ The Presentation of the Elements - Dhātuvibhaṅga Sutta ( Majjhima Nikāya 140)

- ↑ Erich Frauwallner : The Philosophy of Buddhism. [1956]: With a foreword by Eli Franco and Karin Preisendanz, de Gruyter, Berlin 2010, pp. 60–61

- ↑ Samyukta Agama Book 2, quoted from: Jongmae Kenneth Park: The Teachings of Gautama Buddha: An Introduction to Buddhism. Lit, Münster 2006, p. 44

- ^ Critique of Hegelian Dialectics and Philosophy in general . mlwerke.de. Retrieved August 30, 2019.

- ↑ Francisco Flores remote: The Equivalence of Mass and Energy. In: Edward N. Zalta (Ed.): Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy .