Monosodium glutamate

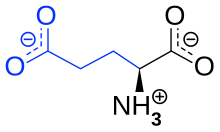

| Structural formula | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| L -monosodium glutamate | |||||||||||||||||||

| General | |||||||||||||||||||

| Surname | Monosodium glutamate | ||||||||||||||||||

| other names | |||||||||||||||||||

| Molecular formula | C 5 H 8 NNaO 4 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Brief description |

colorless, crystalline solid |

||||||||||||||||||

| External identifiers / databases | |||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| properties | |||||||||||||||||||

| Molar mass | 169.13 g mol −1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Physical state |

firmly |

||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point |

163 ° C (decomposition) |

||||||||||||||||||

| solubility |

|

||||||||||||||||||

| safety instructions | |||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Toxicological data | |||||||||||||||||||

| As far as possible and customary, SI units are used. Unless otherwise noted, the data given apply to standard conditions . | |||||||||||||||||||

Monosodium glutamate , also known as sodium glutamate or MNG (English monosodium glutamate , MSG), is the sodium salt of glutamic acid , one of the most common naturally occurring non-essential amino acids . Industrial food manufacturers market and use monosodium glutamate as a flavor enhancer , as it ensures a balanced and rounded overall impression of other flavors and mixes them together. If “monosodium glutamate” is mentioned in this text or in the scientific literature without any additional name ( prefix ), L -monosodium glutamate is meant. D -monosodium glutamate and DL -monosodium glutamate have no practical significance.

Natural occurrence

Monosodium glutamate is the salt of one of the 21 amino acids that make up proteins . Therefore almost all protein foods contain glutamates. Under physiological conditions, monosodium glutamate is dissociated as a glutamate anion (“glutamate” for short). Glutamate is produced in the normal metabolism of all living things. It also serves as a neurotransmitter that binds to glutamate receptors. Some foods such as mushrooms , ripe and especially dried tomatoes , cheese (especially Parmesan ), fish sauce or soy sauce , which are used because of their special flavor, naturally contain large concentrations of free (not bound in proteins) monosodium glutamate, which is chemically mixed with industrially produced monosodium glutamate is identical. The kombu seaweed also contains large quantities and was used by Asian cooks 1,500 years ago because of its flavor-enhancing properties. Glutamate is the most abundant amino acid in human breast milk , at 220 mg per kilogram of breast milk.

In foods and flavors with a naturally high content of monosodium glutamate, the glutamate is produced through the breakdown of proteins by means of proteases (see autolysis ). According to German food law, this is not considered a food additive (in this case as a flavor enhancer ) and does not receive an E number. The release of glutamate through cracks in the cell membranes is increased by cooking , drying or fermenting .

Development as a flavor enhancer

The Japanese chemist Kikunae Ikeda recognized the importance of the natural flavor enhancers used in East Asian cuisine at the beginning of the 20th century and sought the effective principle for the related taste, which he called umami . He had noticed that the Japanese dashi broth made from Katsuobushi and Kombu had a special taste that had not yet been scientifically described at the time and that it differed from the flavors sweet, salty, sour and bitter. In 1908 Ikeda isolated glutamic acid by aqueous extraction from the alga Laminaria japonica (main source for kombu) as a new flavoring substance. To check whether glutamate was responsible for the umami taste, Ikeda researched the taste properties of numerous glutamate salts such as calcium, potassium, ammonium and magnesium glutamate. Of these salts, sodium glutamate was the most soluble and palatable and easily crystallized. In the year of the discovery, a patent was filed for the manufacturing method.

The Suzuki brothers began the commercial production of monosodium glutamate as aji-no-moto, a Japanese word meaning "essence of taste", in 1909 as a licensee. Major manufacturers are the Japanese company Ajinomoto and the Taiwanese company Vedan as well as the South Korean companies Cheil Jedang and Daesang Miwon .

Manufacturing and chemical properties

Since monosodium glutamate was launched on the market, three different manufacturing processes for monosodium glutamate have been practiced industrially, which differ, among other things, in the raw materials used.

The oldest manufacturing process was based on the hydrolysis of vegetable proteins with hydrochloric acid to break peptide bonds (1909–1962). Wheat gluten was initially used for hydrolysis because it contains more than 30 g of glutamate and glutamine in 100 g of protein.

Increasing production volumes made new processes necessary, for which acrylonitrile was offered as a raw material in the 1960s : due to the boom in the polyacrylic fiber industry in Japan, it had been readily available since the mid-1950s and formed the basis for the production of monosodium glutamate from 1962 to 1973.

Currently, the majority of the world's production of monosodium glutamate is made by bacterial fermentation. The sodium salt is produced by partial neutralization of the glutamic acid formed by fermentation . During fermentation, coryneform bacteria, cultivated with ammonia and carbohydrates from sugar beet, sugar cane, tapioca or molasses, excrete amino acids into the culture broth, from which L-glutamate is isolated. The Japanese chemical company Kyōwa Hakkō Kōgyō KK ( 協和 発 酵 工業 株式会社 , today: Kyōwa Hakkō Kirin KK) developed the first industrial fermentation process for the production of L-glutamate. The yield from the conversion of sugar into glutamate and the production throughput in industrial manufacture are constantly being improved. The end product after filtering, concentrating, acidifying and crystallizing is a solution of sodium glutamate in water. Pure monosodium glutamate is a colorless and odorless crystalline solid that is not hygroscopic and dissolves in water with dissociation . Monosodium glutamate is practically insoluble in common organic solvents such as diethyl ether . In general, monosodium glutamate is stable under regular food processing conditions. During the cooking process, monosodium glutamate does not break down, but, as with other amino acids, in the presence of sugar at very high temperatures, a browning or Maillard reaction occurs .

use

Pure monosodium glutamate alone does not have a pleasant taste if it is not combined with a harmonious, hearty smell. As a flavoring substance and in the right amount, monosodium glutamate is able to strengthen other flavor-active components and to balance and round off the overall taste impression of certain dishes. Monosodium glutamate goes well with meat, fish, poultry, many vegetables, sauces, soups and marinades. But unlike other basic flavors with the exception of sucrose, monosodium glutamate only improves the palatability in the right concentration. Excessive monosodium glutamate will ruin the taste of a dish. Although this concentration varies depending on the type of food, the perceived taste in a clear soup drops rapidly with more than 1 g of monosodium glutamate per 100 ml. There is also an interaction between monosodium glutamate and salt (sodium chloride) and other umami substances, such as B. Nucleotides. All must be present in optimal concentration for a maximum taste experience. Monosodium glutamate can be used to reduce the consumption of table salt, which has been linked to the development of high blood pressure and other cardiovascular diseases . The taste of salted foods is better if you reduce the salt level with monosodium glutamate. The sodium content (by weight ) of monosodium glutamate is about three times less (12%) than that of sodium chloride (39%). Other glutamate salts were also used in low-salt soups, but with worse taste results than monosodium glutamate.

On average, every person consumes 600 milligrams of industrially produced monosodium glutamate per day (approx. 4 g per week), a third of which comes from the production of the global market leader General Foods .

Monosodium glutamate is an approved additive in feed . Due to the increased appetite, the fattening animals eat beyond saturation and put on weight more quickly. This effect has also been demonstrated in rats and humans when glutamate and associated receptor blockers are administered.

Safety of monosodium glutamate as a flavor enhancer

Monosodium glutamate has been used to flavor foods since the early 20th century. Extensive studies were conducted during this period to elucidate the properties and safety of monosodium glutamate. Monosodium glutamate as a flavor enhancer is considered safe for human consumption.

The monosodium glutamate symptom complex ("Chinese restaurant syndrome")

The "monosodium glutamate symptom complex" was originally referred to as "Chinese restaurant syndrome" after an anecdote that Robert Ho Man Kwok reported symptoms that he noticed after an American-Chinese meal. Kwok suggested several options for these symptoms, including alcohol from cooking with wine, the sodium content, and the monosodium glutamate seasoning. However, monosodium glutamate came into focus and symptoms have been associated with monosodium glutamate ever since. The effects of wine or salt content have never been studied. Over the years, the list of nonspecific symptoms has increased based on individual reports. Under normal conditions, humans can digest glutamate, which has very low acute toxicity. The oral lethal dose in 50% of the test animals, LD50 , is between 15 and 18 g / kg body weight in rats or mice and is thus five times higher than the LD50 for salt (3 g / kg in rats). The intake of monosodium glutamate as a flavor enhancer and the natural amount of glutamic acid in foods are therefore not a cause for concern for humans from a toxicological point of view. A report by the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology (FASEB) compiled in 1995 for the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) concluded that monosodium glutamate is safe when “consumed in normal amounts is ", and although there is a subgroup of apparently healthy people who react with the monosodium glutamate symptom complex when consuming 3 g monosodium glutamate in the absence of food, the causal link to monosodium glutamate has not yet been established, as the list of the monosodium glutamate symptom complex in witness reports was based. This report also shows that no data exists to support the role of glutamate in chronic and debilitating diseases. A controlled, double-blind, multi-site clinical study found no statistical association between the monosodium glutamate symptom complex and consumption of monosodium glutamate in people who believed they had a negative reaction to monosodium glutamate. There were a few responses, but they were mixed. Symptoms were not observed when monosodium glutamate was given with food.

Because of the strong and unique aftertaste of glutamates, adequate control of bias in experiments includes double-blind, placebo-controlled experimental design and administration in capsules. In a study conducted by Tarasoff and Kelly (1993), 71 fasting participants received 5 g monosodium glutamate followed by a standard breakfast. There was only one response, but to a placebo and from a person who described himself as monosodium glutamate sensitive. In another study by Geha et al. (2000) tested the reaction of 130 test persons who described themselves as being sensitive to monosodium glutamate. Several double-blind study attempts were conducted and only people with at least two symptoms continued to participate in the study. Only two people from the entire experimental group responded on all four occasions. Because of this low prevalence, the researchers concluded that the response to monosodium glutamate was not reproducible.

Further studies examining whether monosodium glutamate causes obesity came up with mixed results. There are several studies examining a reported link between monosodium glutamate and asthma ; the current evidence does not suggest a causal relationship.

Since glutamates are important neurotransmitters in the human brain and play a crucial role in learning and memory, neurologists are currently conducting an ongoing study on the possible side effects of monosodium glutamate in food, but have not yet come to conclusive results that could reveal possible connections .

European Union

The European Union has classified the substance as a food additive with the E number E621. The European Commission considers the use of monosodium glutamate as a food additive to be safe. The German Federal Institute for Risk Assessment and the German Nutrition Society share this view .

Some scientists believe that monosodium glutamate is unlikely to cross the blood-brain barrier in healthy adults. This is proven by animal experiments. Since the blood-brain barrier is more permeable in newborns ( development: blood-brain barrier ), monosodium glutamate is not used in Germany as an additive for baby food .

Australia and New Zealand

Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ) cites "impressive evidence from a large body of scientific studies" to explicitly deny any link between monosodium glutamate and "serious side effects" or "long-lasting effects" and declares monosodium glutamate to be "safe for the general population ". It does mention, however, that less than 1% of the population may experience “transient” side effects such as “headache, numbness / tingling, flushing, muscle cramps and general weakness” if they consume large amounts of monosodium glutamate in a single meal . Individuals who consider themselves sensitive to monosodium glutamate are asked to have this observation confirmed by an appropriate clinical examination.

In Australia and New Zealand , the use of monosodium glutamate as a food additive on packaged foods must be reported. The label must state the food additive's class name (e.g., flavor enhancer) followed by either the food additive's name, monosodium glutamate, or its INS ( International Numbering System ) number, 621.

United States

The US Food and Drug Administration has recognized monosodium glutamate as generally safe. Monosodium glutamate is one of several forms of glutamic acid found in food, mainly because glutamic acid is an amino acid that is found everywhere in nature. Glutamic acid and its salts can also be found in a wide variety of other additives, including hydrolyzed vegetable proteins , autolyzed yeast , hydrolyzed yeast , yeast extract , soy extracts and protein isolate, which must be labeled under these common and common names. Since 1998, monosodium glutamate is no longer allowed to fall under the term “spices and flavorings”. The food additives disodium inosinate and disodium guanylate , which are ribonucleotides , are usually used in conjunction with ingredients containing monosodium glutamate. However, the food industry today uses the term "natural flavor" when glutamic acid (monosodium glutamate with no associated sodium salt) is used. Due to the lack of regulations by the FDA, it is impossible to find out what proportion of a “natural flavor” is actually glutamic acid.

The FDA considers labels such as “No monosodium glutamate” or “No added monosodium glutamate” to be misleading if the food contains ingredients that are sources of free glutamate, such as: B. hydrolyzed protein. In 1993, the FDA proposed adding "(contains glutamate)" to the common or common name of certain protein hydrolyzates that contain significant amounts of glutamate.

In the 2004 edition of his book On Food and Cooking , author Harold McGee states that "[after much research] toxicologists have concluded that monosodium glutamate is a harmless ingredient for most people, even in large quantities."

literature

- Geha, RS. et al .: Multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multiple challenge evaluation of reported reactions to monosodium glutamate . In: J Allergy Clin Immunol . 2000 106, 5, pp. 973-980; PMID 11080723 .

Web links

- Brief information from the chair “Psychology of Eating and Drinking” at Heidelberg University (PDF file; 427 kB)

- Information from the European Food Information Center

- The Facts on Monosodium Glutamate (EUFIC)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Entry on E 621: Monosodium glutamate in the European database for food additives, accessed on August 11, 2020.

- ↑ entry to SODIUM GLUTAMATE in CosIng database of the European Commission, accessed on 20 April 2020th

- ↑ a b c data sheet L-Glutamic acid monosodium salt hydrate, ≥99% (HPLC), powder from Sigma-Aldrich , accessed on December 1, 2019 ( PDF ).

- ↑ Entry on sodium hydrogen glutamate in the GESTIS substance database of the IFA , accessed on April 26, 2014(JavaScript required) .

- ^ Entry on monosodium glutamate in the ChemIDplus database of the United States National Library of Medicine (NLM) .

- ↑ Entry on sodium l-glutamate. In: Römpp Online . Georg Thieme Verlag, accessed on April 26, 2014.

- ^ Joint FAO / WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA), Monograph for Glutamic acid and its salts , accessed on December 9, 2014.

- ^ Ninomiya K: Natural occurrence . In: Food Reviews International . 14, No. 2 & 3, 1998, pp. 177-211. doi : 10.1080 / 87559129809541157 .

- ↑ a b Loliger J: Function and importance of Glutamate for Savory Foods . In: Journal of Nutrition . 130, No. 4s Suppl, April 2000, pp. 915s-920s. PMID 10736352 .

- ↑ Yamaguchi S: Basic properties of umami and effects on humans . In: Physiology & Behavior . 49, No. 5, May 1991, pp. 833-841. doi : 10.1016 / 0031-9384 (91) 90192-Q . PMID 1679557 .

- ↑ n-tv.de: More taste in food: What is glutamate? , accessed March 24, 2012.

- ↑ Ikeda K: New seasonings . In: Chem Senses . 27, No. 9, November 2002, pp. 847-849. doi : 10.1093 / chemse / 27.9.847 . PMID 12438213 .

- ↑ Lebensmittellexikon.de: Glutamat , accessed on March 24, 2012.

- ↑ a b Alex Denton: If MSG is so bad for you, why doesn't everyone in Asia have a headache? , The Guardian of July 10, 2005, accessed December 1, 2015.

- ↑ Hans Konrad Biesalski : Micronutrients as the engine of evolution. Springer-Verlag, 2015, ISBN 978-3-642-55397-4 , p. 164.

- ↑ Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft , Senate Commission for the Assessment of the Harmlessness of Foods: Opinion on the potential involvement of oral glutamate intake in chronic neurodegenerative diseases. of April 8, 2005. p. 3. ( PDF ).

- ↑ a b Ikeda K: New seasonings . In: Chem Senses . 27, No. 5, August, pp. 847-849.

- ^ Lindemann B, Ogiwara Y, Ninomiya Y: The discovery of umami . In: Chem Senses . 27, No. 9, November 2002, pp. 843-844. doi : 10.1093 / chemse / 27.9.843 . PMID 12438211 .

- ↑ Ikeda K (1908). "A production method of seasoning mainly consists of salt of L-glutamic acid". Japanese Patent 14804.

- ↑ a b Yamaguchi S, Ninomiya K: What is umami? . In: Food Reviews International . 14, No. 2 & 3, 1998, pp. 123-138. doi : 10.1080 / 87559129809541155 .

- ↑ Kurihara K: Glutamate: from discovery as a food flavor to role as a basic taste (umami)? . In: The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition . 90, No. 3, September 2009, pp. 719S-722S. doi : 10.3945 / ajcn.2009.27462D . PMID 19640953 .

- ↑ a b c Chiaki Sano: History of glutamate production . In: The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition . 90, No. 3, September 2009, pp. 728S-732S. doi : 10.3945 / ajcn.2009.27462F . PMID 19640955 .

- ^ Statement by the Federal Cartel Office on the takeover of Orsan in 2003. PDF . Retrieved March 17, 2012.

- ↑ Harold King: d-Glutamic Acid In: Organic Syntheses . 5, 1925, p. 63, doi : 10.15227 / orgsyn.005.0063 ; Coll. Vol. 1, 1941, p. 286 ( PDF ).

- ↑ Yoshida T: Industrial manufacture of optically active glutamic acid through total synthesis . In: Chem Ing Tech . 42, 1970, pp. 641-644.

- ↑ Kinoshita S, Udaka S, Shimamoto M: Studies on amino acid fermentation. Part I. Production of L-glutamic acid by various microorganisms . In: J Gen Appl Microbiol . 3, 1957, pp. 193-205.

- ↑ Win. C. (Ed.): Principles of Biochemistry . Brown Pub Co., Boston, MA 1995.

- ↑ Rolls ET: Functional neuroimaging of umami taste: what makes umami pleasant? . In: The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition . 90, No. 3, September 2009, pp. 804S-813S. doi : 10.3945 / ajcn.2009.27462R . PMID 19571217 .

- ↑ Kawamura Y, Kare MR (Ed.): Umami: a basic taste . Marcel Dekker Inc., New York, NY 1987.

- ↑ Dieter Klaus; Joachim Hoyer; Martin Middeke: Salt restriction for the prevention of cardiovascular diseases . In: Deutsches Ärzteblatt . 107, No. 26, 2010, pp. 457-462. doi : 10.3238 / arztebl.2010.0457 .

- ↑ Ole Mouritsen: Umami. Columbia University Press, 2014, ISBN 978-0-231-53758-2 , p. 55.

- ↑ Yamaguchi S, Takahashi C: Interactions of monosodium glutamate and sodium chloride on saltiness and palatability of a clear soup . In: Journal of Food Science . 49, No. 1, January 1984, pp. 82-85. doi : 10.1111 / j.1365-2621.1984.tb13675.x .

- ↑ Ball P, Woodward D, Beard T, Shoobridge A, Ferrier M: Calcium diglutamate improves taste characteristics of lower-salt soup . In: Eur J Clin Nutr . 56, No. 6, June 2002, pp. 519-523. doi : 10.1038 / sj.ejcn.1601343 . PMID 12032651 .

- ↑ Alex Renton: If MSG is so bad for you, why doesn't everyone in Asia have a headache? In: The Observer: Food & Drink, July 10, 2005 (see above)

- ↑ European Commission: Community Register of Feed Additives pursuant to Regulation (EC) No 1831/2003 (PDF; 7.6 MB) Appendixes 3 & 4, Directorate D - Animal Health and Welfare, Unit D2 - Feed, p. 192, 15 Feb. 2010.

- ↑ Hermanussen M. et al .: Obesity, voracity and short stature: the impact of glutamate on the regulation of appetite. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2006; 60, pp. 25-31, PMID 16132059 .

- ↑ a b Walker R, Lupien JR: The safety evaluation of monosodium glutamate . In: Journal of Nutrition . 130, No. 4S Suppl, April 2000, pp. 1049S-1052S. PMID 10736380 .

- ^ A b Freeman, M: Reconsidering the effects of monosodium glutamate: A literature review . In: Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practicioners . 18, No. 10, 2006, pp. 482-486. doi : 10.1111 / j.1745-7599.2006.00160.x . PMID 16999713 .

- ^ Raiten DJ, Talbot JM, Fisher KD: Executive Summary from the Report: Analysis of Adverse Reactions to Monosodium Glutamate (MSG) . In: Journal of Nutrition . 126, No. 6, 1996, pp. 1743-1745. PMID 7472671 .

- ↑ RS Geha, A. Beiser, C. Ren, R. Patterson, PA Greenberger, LC Grammer, AM Ditto, KE Harris, MA Shaughnessy, PR Yarnold, J. Corren, A. Saxon: Review of alleged reaction to monosodium glutamate and outcome of a multicenter double-blind placebo-controlled study. In: The Journal of Nutrition. Volume 130, Number 4S Suppl, April 2000, pp. 1058S-1062S, PMID 10736382 (review).

- ↑ a b Tarasoff L., Kelly MF: monosodium L-glutamate: a double-blind study and review . In: Food Chem. Toxicol. . 31, No. 12, 1993, pp. 1019-1035. doi : 10.1016 / 0278-6915 (93) 90012-N . PMID 8282275 .

- ^ Freeman M .: Reconsidering the effects of monosodium glutamate: a literature review . In: J Am Acad Nurse Pract . 18, No. 10, October 2006, pp. 482-6. doi : 10.1111 / j.1745-7599.2006.00160.x . PMID 16999713 .

- ^ Walker R: The significance of excursions above the ADI. Case study: monosodium glutamate . In: Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. . 30, No. 2 Pt 2, October 1999, pp. S119-S121. doi : 10.1006 / rtph.1999.1337 . PMID 10597625 .

- ↑ Willams, AN, and Woessner, KM: Monosodium glutamate 'allergy': menace or myth? . In: Clinical & Experimental Allergy . 39, No. 5, 2009, pp. 640-646. doi : 10.1111 / j.1365-2222.2009.03221.x .

- ↑ Z Shi, ND Luscombe-Marsh, GA Wittert, B Yuan, Y Dai, X Pan, AW Taylor: Monosodium glutamate is not associated with obesity or a greater prevalence of weight gain over 5 years: Findings from the Jiangsu Nutrition Study of Chinese adults . In: The British journal of nutrition . 104, No. 3, 2010, pp. 457-463. doi : 10.1017 / S0007114510000760 . PMID 20370941 .

- ↑ Nicholas Bakalar: Nutrition: MSG Use Is Linked to Obesity , The New York Times . August 25, 2008. Retrieved November 10, 2010. "Consumption of monosodium glutamate, or MSG, the widely used food additive, may increase the likelihood of being overweight, a new study says."

- ↑ Stevenson, DD: Monosodium glutamate and asthma . In: J. Nutr. . 130, No. 4S Suppl, 2000, pp. 1067S-1073S. PMID 10736384 .

- ↑ NJ Maragakis, JD Rothstein: Glutamate transporters in neurologic disease. In: Archives of neurology. Volume 58, number 3, March 2001, pp. 365-370, doi : 10.1001 / archneur.58.3.365 , PMID 11255439 (Review): “ Glutamate is the primary excitatory amino acid neurotransmitter in the human brain. It is important in synaptic plasticity, learning, and development. Its activity at the synaptic cleft is carefully balanced by receptor inactivation and glutamate reuptake. When this balance is upset, excess glutamate can itself become neurotoxic. [...] This overactivation leads to an enzymatic cascade of events ultimately resulting in cell death. ”

- ↑ Regulation (EU) No. 1129/2011 of the Commission of November 11, 2011 amending Annex II of Regulation (EC) No. 1333/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council with regard to a list of food additives of the European Union

- ↑ Written question E-0119/01 by Ria Oomen-Ruijten (PPE-DE) to the Commission on possible health risks from the flavor enhancers E621 and E632 (glutamate) , accessed on March 19, 2012

- ↑ Hypersensitivity reactions to glutamate in food (PDF; 10 kB) Federal Institute for Risk Assessment (BfR). Retrieved March 12, 2012.

- ↑ Is the flavor enhancer glutamate harmful to health? . German Nutrition Society (DGE). Retrieved March 12, 2012.

- ↑ Statement on the potential involvement of oral glutamate intake in chronic neurodegenerative diseases (University of Kaiserslautern) (PDF; 143 kB).

- ↑ MSG In Food . In: Food Standards Code . Food Standards Australia New Zealand. Retrieved May 17, 2010.

- ↑ Standard 1.2.4 Labeling of Ingredients . In: Food Standards Code . Food Standards Australia New Zealand. Retrieved May 15, 2010.

- ↑ FDA Database of Select Committee on GRAS Substances L-glutamic acid, L-glutamic acid hydrochloride, monosodium L-glutamate, monoammonium L-glutamate, and monopotassium L-glutamate ( Memento of May 23, 2011 in the Internet Archive ), accessed on May 18 , 2011 March 2012.

- ↑ McGee, Harold, On Food and Cooking, the Science and Lore of the Kitchen , 2004.