National treasures of Japan

The national treasures of Japan ( Japanese 国宝 Kokuhō ) are the most precious "material cultural goods" of Japan. The classification as a " material cultural asset " is carried out by the " Office for Cultural Affairs " ( 文化 庁 Bunka-chō ), a subdivision of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sport, Science and Technology , and the Minister of Education appoints it as a national treasure . A material cultural asset is a cultural asset that has a particular historical or artistic value and that can be classified either as a structure or building or as an object of art or craftsmanship. The classification is based on the provisions of the "Law for the Protection of Material Cultural Assets " ( 文化 財 保護 法 , Bunkazai hōgohō ) (especially Section 2, Paragraph 2) and based on the ordinances of the local authorities ( 地方 公共 団 体 Chihōkōkyōdantai ). The law distinguishes between “material” and “immaterial” (literally: informal) cultural treasures, which are not the subject of this article. A material cultural asset must be an example of extraordinary craftsmanship and significant for cultural history or science.

About 20% of the material cultural treasures of Japan are buildings such as castles , Buddhist temples, Shinto shrines or residences. The remaining 80% are paintings, scrolls, sutras , sculptures made of wood, bronze, lacquer or stone, handicrafts such as pottery, lacquer carvings, metal goods such as Japanese swords , textiles and historical and archaeological materials. The cultural treasures include items from the ancient times to the beginning of Japanese modernity ( Meiji period ).

Japan has a comprehensive system of ordinances to protect, preserve and classify its cultural heritage. The measures for the protection of designated cultural assets include restrictions on the possibilities of change, transfer and export, but also financial support and tax relief. The Office for Cultural Affairs assists the owners with restoration, administration and public exhibition issues. These efforts are complemented by legislation that protects the surroundings of a structure and which for some time has also included the necessary restoration techniques.

Most of the national treasures are in the Kansai region, the ancient cultural center of Japan, about a fifth in Kyoto . Works of art or handicrafts are mostly privately owned or are kept in museums such as the Tokyo National Museum or the Kyoto National Museum. Religious objects, on the other hand, are usually kept in temples, shrines or affiliated museums and treasuries.

history

Beginnings of the protection of cultural property

Originally, the cultural assets were owned by Buddhist temples, Shinto shrines or by aristocratic or samurai families. The feudal period ended abruptly in 1867/68 when the Edo period led to the Meiji Restoration . In the course of, the early Meiji period , following movement "Eliminates the Buddhas, destroyed the Buddhist scriptures" ( 廃仏毀釈 haibutsu kishaku ) caused by the separation of Shinto and Buddhism ( shinbutsu bunri ) and by an anti-Buddhist movement, many were Buddhist Buildings and works of art destroyed. In 1871 the government, emblematic of the ruling elite, confiscated land from temples. Feudal lords' possessions have been expropriated, historic castles and residences destroyed, and an estimated 18,000 temples have been closed. During this period, the beginning of industrialization and the turn to the West also had a negative impact on Japan's cultural heritage: Buddhist and Shinto institutions became impoverished, temples fell into disrepair, and valuable cultural assets were exported.

In 1871 the Daijō-kan issued an order based on recommendations from the universities to protect Japanese antiquities, regarding the "possibilities of preserving ancient artifacts" ( 古 器 旧 物 保存 方 Koki kyūbutsu hozonkata ). This arrangement determined that prefectures, temples and shrines had to draw up lists of important buildings and works of art. However, these efforts were unsuccessful in the face of radical westernization. In 1880, the government granted funds to preserve ancient temples and shrines. Over the next 14 years, up to 1894, 539 temples and shrines received government funding for repairs and reconstruction. For example, the five-story pagoda of Daigo-ji ( Kyōto ), the main hall of Tōshōdai-ji ( Nara ) and the main hall of Kiyomizu-dera (Kyōto) were repaired during this time . A survey led by Okakura Kakuzō and Ernest Fenollosa between 1888 and 1897 saw 210,000 objects of artistic or historical value being assessed and cataloged.

Law for the Preservation of Old Shrines and Temples

On June 10, 1897, a law was passed for the first time with the "Law for the Preservation of Old Shrines and Temples" ( 古 社 寺 保存 Gesetz Koshaji Hozonhō , i. Act 49), which specifically stipulated the preservation of historical art and architecture in Japan. Drafted under the direction of the architect and architectural historian Itō Chūta , the law established state funding for the preservation of buildings and the restoration of works of art in 20 articles. The law was applied to architecture and works of art that were part of buildings on the condition that historical uniqueness and exceptional quality are proven (Article 2). Applications for financial support were to be submitted to the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (Article 1), while the responsibility for preservation and restoration was the responsibility of the local officials. Restoration work was financed directly from the state budget (Article 3).

In December 1897, a second law was also passed that contained additional provisions to classify works of art that are in the possession of temples or shrines as “national treasures ” ( 国宝 Kokuhō ) and architecture that serves religious purposes as “specially protected buildings” ( 特別 保護 建造 物 tokubetsu hogo kenzōbutsu ). In addition to the main characteristics of “artistic creativity” and “value as a historical source in addition to the possibility of connecting history”, age also played a role. The nomination of works of art could be in the following categories: paintings, sculpture, calligraphy, books, and craftsmanship. Swords were added at a later date. The law was limited to items owned by religious institutions, while privately owned items were not protected by the law. The funds for restoring works of art and buildings were increased from 20,000 yen to 150,000 yen. In addition, fines were imposed for the destruction of cultural property. Owners were asked to register objects once they had been appointed in the newly created museums so that the museums would have the opportunity to purchase the pieces in the event of a sale. The new law initially named 44 temples and shrines and 155 relics, including the main hall of the Hōryū-ji .

The laws of 1897 are the basis for today's monument protection regulations. At the time they were enacted, only England, France, Greece and four other European countries had comparable laws. A direct result of these laws was the restoration of the Tōdai-ji's main hall , which began in 1906 and was completed in 1913. A year later, in 1914, the management of the cultural property was transferred from the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications to the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology .

Extension of the protection of cultural property

Modernization changed the Japanese landscape at the beginning of the 20th century and posed a threat to architectural and natural monuments. Well-known members of societies such as the “Imperial Ancient Sites Survey Society” or the “Society” for the Investigation and Preservation of Historic Sites and Aged Trees "(" Society for the investigation and preservation of historic sites and old trees ") supported and obtained a resolution on protective measures in the Japanese House of Lords ( Kizokuin ). Ultimately, these efforts led in 1919 to the enactment of the "Law for the Preservation of Historical Places, Landscapes and Natural Monuments" ( 史蹟 名勝 天然 紀念物 保存 法 Shiseki meishō enrenkinenbutsu hozonhō ), which protected and cataloged such goods in the same way as temples, shrines and works of art .

In 1929, 1,100 cultural assets were declared worthy of protection by the “Law for the Preservation of Old Shrines and Temples”. Most of these goods were religious buildings from the 7th to 17th centuries. Approximately 500 buildings had been extensively restored with around 90% of state funds. Most of the restoration work carried out in the Meiji period used new techniques and materials.

On July 1, 1929, the law for the preservation of national treasures ( 国宝 保存 法Kokuhō hozonhō ) was passed. This law replaced the two laws of 1897 and extended protection to national treasures owned by public and private institutions and privately owned by individuals in an effort to prevent the export or dismantling of cultural assets. The focus of protection was not only on religious structures, but also on castles, teahouses, residences and new religious buildings. With the Meiji Restoration and the end of the feudal period, many buildings had become private property. Two of the last residential buildings declared a national treasure were the Yoshimura residence in Osaka (1937) and the Ogawa residence in Kyoto (1944). The new law only permitted the subsequent reconstruction of national treasures once they had been appointed with official approval.

The restoration of the entrance gate (Nandaimon) in the Tōdai-ji temple in 1930 was carried out according to improved standards: an architect supervised the work on site. Detailed reports on the restoration, which included plans, results, expert opinions, historical sources and documentation of the work carried out, became the rule from now on. In the 1930s, about 70 to 75% of the restoration costs were financed from the state budget.

At the beginning of the 1930s, Japan also suffered from the Great Depression . In order to prevent works of art that had not yet been declared a national treasure from being exported due to the economic crisis, a “law for the preservation of important works of art” ( 重要 美術品 等 ノ 保存 ニ 関 ス ル 法律 Jūyō bijutsuhin tōno was passed in April 1933 hozon ni kansuru hōritsu ). This law enabled a simplified appointment procedure for temporary protection, including against export. About 8000 objects were protected by this law. By 1939, nine categories (paintings, sculptures, architecture, documents, books, calligraphy, swords, handicrafts and archaeological sources) with 8,282 cultural objects had been declared national treasures whose export was prohibited.

During the Second World War, many buildings that had become national treasures were camouflaged and protected by water tanks and firewalls. Nevertheless, 206 of these buildings, including Hiroshima Castle , were destroyed in the final months of the war . The Buddhist text Tōdaiji Fujumonkō, declared a national treasure in 1938, burned in 1945 as a result of the war.

The Cultural Property Protection Act of 1950

The " Cultural Property Protection Act " ( 文化 財 保護 法 Bunkazai hogohō ) of May 30, 1950, which came into force on August 29 of the same year, has since comprehensively regulated Japanese monument law.

Current developments

Since June 9, 1951, national treasures have been declared under the Monument Protection Act . This monument protection law, which is currently still valid law, has since been supplemented by extensions and additional laws that redesigned the system for preservation and protection and expanded its framework to include a large number of other cultural assets.

In the 1960s, the scope of the protected buildings was expanded to include Western architecture. In 1966 the "Law for the Protection of Old Capitals" was passed. It dealt mainly with the old Japanese capitals: Kamakura , Heijō-kyō ( Nara ), Heian-kyō ( Kyōto ), Asuka-kyō (today: Asuka , Nara Prefecture ), Fujiwara-kyō , Tenri , Sakurai , and Ikaruga , with So areas that are home to a multitude of national treasures. This law was expanded in 1975 to include buildings that were not located in capital cities.

The second notable change in 1975 was that the government extended protection to include techniques used to preserve cultural assets. This measure had become necessary because of the lack of skilled craftsmen due to industrialization. The protected techniques included, for example, the stretching of pictures and calligraphy on scrolls, the repair of lacquer work and sculptures made of wood, the production of Nō masks, costumes and instruments.

In 1996 the two-tier system of “national treasure” and “important cultural asset” was expanded to include “registered cultural assets”. Originally restricted to buildings, this new classification functioned as a waiting list for designation as an important cultural asset. A variety of structures, mainly industrial buildings and historical residences from the late Edo period to the early Shōwa period , were registered in the new system. Registration meant fewer obligations for the owner compared to important cultural and national treasures. Since the end of the 20th century, the Office for Cultural Affairs has focused its appointment on structures that are on the one hand in underrepresented areas and on the other hand on structures that were built between 1869 and 1930. The office has already recognized the insufficient equipment with the necessary building materials and tools for the restoration work. In 1999, official monuments protection offices were set up in the prefectures and cities.

The Tōhoku earthquake in 2011 damaged a total of 714 cultural assets.

Selection process

Material cultural assets of high historical, artistic or scientific value are listed in a three-tier system. Goods that are to be preserved and that are still used at the same time are cataloged as “ Registered Cultural Properties” . Important objects are shown as “ Important Cultural Properties” .

Important cultural assets of extraordinary craftsmanship, particularly high cultural and historical value or an extraordinary value for science can be designated as a "national treasure". In order to obtain an appointment, the owner of an important cultural property can contact the Office for Cultural Affairs or be contacted by them and receive information on registration. In the event that the Office contacts the owner, it will obtain the owner's consent in advance, although this is not legally required. The office then contacts the “Council for Cultural Affairs”. This council has five members, chosen by the Minister of Education for their excellent view of and knowledge of culture. If these members vote in favor of a nomination, the cultural property is placed on a registration list, the owner is informed of the decision and a public announcement is made in an official gazette. The guideline on appointment is deliberately interpreted with moderation in order to keep the number of declared cultural assets low. Currently between one and five estates are appointed annually.

Categories

The Office for Cultural Affairs names material cultural property in 13 categories as national treasure, depending on the type of cultural property. In general, the office differentiates between structures and buildings ( 建造 物 Kenzōbutsu ) on the one hand and works of art or handicrafts ( 美術 工 芸 品 Bijutsu kōgeihin ) on the other. The main categories are still broken down into sub-categories. The 216 monuments are divided into six sub-categories, the 866 works of art in seven sub-categories.

Castles

The category Burg ( 城郭 Jōkaku ) includes eight national treasures in four different places: Himeji-jō , the Matsumoto Castle , the Inuyama Castle and the Castle Hikone , including 16 buildings such as towers , towers and walkways. The Himeji-jō, the most visited castle in Japan and a world cultural heritage site , has five national treasures, the remaining three each have a national treasure. These buildings, which date from the Sengoku period , represent the high point in the construction of Japanese castles . Made of wood and built on stone foundations, they are military fortifications, political, cultural and economic centers and at the same time the residences of the daimyo and their followers .

Modern and historical residences

Residences consist of two categories: modern residential buildings ( 住居 , Jūkyo ), from the Meiji period, and historical residences ( 住宅 , Jūtaku ), up to the Edo period . The only modern national treasure is the Imperial Residence Akasaka from 1909. The category of historical residences, however, comprises 14 national treasures from 1485 to 1657. Ten of these are in Kyoto. These structures include Japanese tea houses , shoin ( 書院 , study ) and reception rooms.

Shrines

The shrines category ( 神社 , jinja ) include national treasures such as main halls (honden), oratories , gates, pagans ( 幣 殿 , areas for sacrifice ) and haredono ( 祓 殿 , areas for purification ). Currently this category includes 38 national treasures from the late Heian period (12th century) to the late Edo period. Following the tradition of Shikinen sengūsai ( 式 年 遷 宮 祭 ), the buildings were renewed at regular intervals while maintaining their original appearance. In this way, the old architectural styles have been continuously reproduced through the centuries up to the present day. The oldest shrine building still standing is the main hall of Ujigami-jinja from the 12th century. About half of these national treasures are located in the three prefectures of the Kansai region: in Kyoto , Nara and Shiga . In addition, five national treasures belong to the Nikkō Tōshō-gū .

temple

This category brings together buildings belonging to Buddhist temples ( 寺院 , Jiin ), such as the main hall, pagodas , bell towers, corridors, etc. a. At the moment, 152 national treasures belong to this category, including the Hōryū-ji from the 6th century and the Hall of the Great Buddha in Tōdai-ji and thus the world's oldest and largest wooden structure. The Hōryū-ji also has 18 buildings, the largest number of designated national treasures. Buddhist architecture spans more than 1000 years, from the Asuka period (6th century) to the Edo period (in the 19th century). More than three-quarters of this cultural property is in the Kansai region, including 60 temples in Nara Prefecture and 29 in Kyoto Prefecture.

Other structures

The last sub-category “other structures” ( そ の 他 , sono hoka ) comprises three structures that could not be assigned to any of the above categories. it is the northern of the two Nō stages in Nishi Hongan-ji , the auditorium of the former Shizutani school in Bizen and the Roman Catholic Ōura church in Nagasaki . The Nō stage dates back to 1581 and is the oldest of its kind. It consists of a side stage for the choir ( 脇 座 , Wakiza ), a rear part for the musicians ( 後座 , Atoza ) and an entrance to the main stage ( 橋 掛 , Hashigakari ).

The Shizutani School was built as a single-storey educational facility in the middle of the Edo period, 1701. It has a hipped roof in the Japanese style of the irimoya-zukuri . Precious woods such as the Japanese zelkove , cedar and the camphor tree were mainly used for the construction .

The Ōura Church was built in 1864 by the French priest Bernard Petitjean to commemorate the 26 martyrs of Nagasaki who were crucified in Nagasaki on February 5, 1597. The front of the building faces the site of the crucifixion, Nishizaka Hill. It is designed in Gothic style and is considered to be the oldest surviving wooden church in Japan.

Historical documents

Valuable documents of Japanese history are assigned to the "Komonjo" ( 古 文書 ) category. The category includes 60 documents, from letters to diaries to file entries. One national treasure is a linen card, another is an inscription in a stone. All other documents are written with a brush, which are often significant examples of early calligraphy . The documents date from the 7th to the 19th century. About half of the national treasures in this category are in Kyoto.

Archaeological materials

With 44 national treasures , the category “Archaeological Materials” ( 考古 資料 , Kōkoshiryō ) includes some of the oldest pieces of Japanese cultural heritage . Many of these objects are grave goods or offerings for the foundation of a temple, which as a result come from graves, burial mounds ( Kofun ) , sutrene mounds ( 経 塚 , Kyōzuka ) or other archaeological excavation sites. The oldest pieces are flame-shaped pottery and dogū figures from the Jōmon period . In addition, bronze mirrors, bells, jewelery, old swords and knives belong to the national treasures of this category. The most recent find is a hexagonal stone stele that dates back to the Nanboku-chō period, 1361. Most of this archaeological material is kept in museums. Six of them in the Tokyo National Museum .

Handicrafts

252 national treasures are categorized as "handicrafts" ( 工 芸 品 , Kōgeihin ), 122 of them in the sword subcategory .

- Swords

Currently 110 swords and twelve sword stands belong to this sub-category. The oldest sword comes from the Asuka period (7th century). 86 national treasures in this sub-category date from the Kamakura period ; the youngest swords from the Muromachi period .

- Other handicrafts

This sub-category includes pottery from Japan, China and Korea, metalwork such as bronze mirrors and Buddhist ceremonial objects, and lacquerware such as boxes, furniture and dishes, mikoshi , textiles and armor. The national treasures, which date back to the 7th century, can be found in Buddhist temples, Shinto shrines and museums. This category also includes sacred treasures that were presented by admirers to the shrines: Asuka Shrine, Kasuga Taisha and Kumano Hayatama Taisha . The gifts, consisting of clothing, household items, etc., were intended for the deities of the shrines.

Historical materials

Three national treasures with a multitude of individual items are cataloged as "historical materials" ( 歴 史 資料 , Rekishi shiryō ). The first ensemble includes 1251 individual pieces from the Shō family, which ruled the Ryūkyū Kingdom on the Ryūkyū Islands between the 15th and 19th centuries . The named individual pieces are chronologically assigned to the second ruling family of the Shō (16th to 19th centuries) and they are kept in the historical museum in Naha . This group of individual items includes 1166 documents and records, including among other things construction plans and lists of burial objects. 85 of these unique pieces are clothing and furniture.

The second ensemble of individual pieces includes paintings, documents, ceremonial objects, dishes and clothing that Hasekura Tsunenaga brought back from Europe from his trade mission (1613–1620). Sent by Date Masamune , the daimyo of the Tōhoku region, Hasekura traveled via Mexico and Madrid to Rome and back to Japan. In the museum in Sendai there is a group of 47 individual items, including a document of Roman citizenship from 1615, a portrait of Pope Paul V and a picture of Hasekura praying after he converted in Madrid. In addition, 19 religious paintings, images of saints, rosaries, a cross, medals and 25 pieces of tableware and clothing, such as priestly robes, an Indonesian kris and a dagger from Sri Lanka, are part of this small selection of national treasures that are in Sendai.

The third ensemble includes 2,345 pieces from the Edo period related to the surveyor and cartographer Inō Tadataka . These national treasures are in the custody of the inō tadataka Museum in Katori in Chiba Prefecture . Specifically, there are 787 maps and drawings, 569 documents and records, 398 letters, 528 books and 63 devices such as surveying instruments.

painting

In this category, ( 絵 画 , Kaiga ), 158 Japanese and Chinese paintings from the Nara period to the early modern period of the 19th century are listed. The paintings show Buddhist motifs, landscapes, portraits and scenes at court. Different materials were used for the paintings: 90 national treasures are hanging scroll paintings ( kakemono ), 38 are emakimono , 20 wall screens or painted Fusuma and three albums. Many of these national treasures are in museums such as the Tokyo National Museum , the Kyoto National Museum, and the Nara National Museum . With 50 paintings, Kyoto has most of these national treasures, followed by Tokyo with 45 objects.

Sculptures

Sculptures of Shinto and Buddhist deities or of clergy who are venerated as the founders of a temple are listed in the "Sculptures" ( 彫刻 , Chokoku ) category . Of the 126 sculptures, which are classified from the Asuka period (7th century) to the Kamakura period (13th century), 94 are made of wood, eleven of bronze, eleven of lacquer and seven of clay. The stone Buddha in Usuki is an ensemble of sculptures. The size of the sculptures ranges from 10 cm to 13 m. An exception is the large Buddha statue in Kamakura with 15 m.

70 of these 126 national treasures are located in Nara prefecture , 37 in Kyoto prefecture . With a few exceptions, Buddhist temples house the sculptures, of which the two temples Hōryū-ji and Kōfuku-ji each have 17 pieces. Another national treasure can be found in the Ōkura Shūkokan art museum ( 大 倉 集 古 館 ) in Tokyo, in the Nara National Museum and in the Yoshino Mikumari Shrine in Yoshino (Nara). The ensemble of sculptures depicting four Shinto deities is in the Kumano Hayatama Taisha .

Papers / documents

Written national treasures such as the transcription of sutras , poetry, history and specialist books belong to the category of "written documents" ( 書 跡 ・ 典籍 , Shoseki Tenseki ). These 223 national treasures originated mainly in the period from Japanese antiquity to the Middle Ages ( Muromachi period ). Most of the documents are brush-written on paper and are valuable examples of masterful calligraphy.

Measures to preserve and use

The "Law for the Protection of Cultural Property" (1950) laid down measures to ensure the preservation and use of national treasures. These immediate measures are supplemented by indirect efforts to protect the environment (in the case of architectural national treasures) or by efforts to find the techniques necessary for the restoration work.

The owner or manager of a national treasure is responsible for its administration and restoration. If a cultural property is lost, destroyed, damaged, changed, relocated or changed hands, you are obliged to notify the Office for Cultural Affairs. Changes require a permit and the office must therefore be informed 30 days before repairs are carried out (Section 43). If required, the owner must provide information and inform the head of the office about the state of the cultural property (Section 54). If a national treasure has been damaged, the head of the office for cultural affairs has the right to demand that the owner or administrator repair the cultural property. If the owner does not follow this request, the head of the office can carry out the repairs. If a national treasure is sold, the government reserves the right of first refusal (Section 46). In general, the movement of national treasures is restricted and exports from Japan are prohibited.

If a cultural property is granted state support, the head of the office for cultural affairs has the right to recommend or prescribe access to the public or the lending to a museum (§ 51). This requirement that private owners allow access to the cultural property or have to cede rights was one reason why property for which the Imperial Court Office is responsible, with the exception of the Shōsōin , was not declared a national treasure. The imperial court office is of the opinion that the imperial property is adequately protected and therefore does not require any additional protection through the “Law on the Protection of Cultural Property”.

Protective measures are not just limited to the duties of the owner. In addition to the prestige that comes with being designated a national treasure, owners also benefit from benefits such as exemption from local taxes, including taxation on business assets and property tax, as well as reduced taxes on property transfers.

The Office for Cultural Affairs also helps owners and administrators with the management, restoration and public display of the national treasures. A custodian of a national treasure can be appointed, usually a local body, if the following conditions are met: the owner cannot be located, the cultural property is damaged or insufficiently protected, or if the cultural property is not accessible to the public.

The government also provides grants for repairs, maintenance, and the construction of fire protection and other civil protection facilities. Subsidies are available to municipalities for the acquisition of land or buildings that are cultural property. In fiscal year 2009, the budget allocated to the Department of Cultural Affairs for the preservation of national treasures and the protection of important cultural property was 12 million yen, which corresponds to 11.8% of the total budget.

Key figures

The Bureau of Cultural Affairs publishes the list of national treasures and other Japanese cultural objects in the National Cultural Property Database. As of July 1, 2010, the database contained 866 national treasures in the main category: Arts and Crafts and 216 in the main category: Structures and Buildings.

About 89% of the national architectural treasures are religious buildings. Residences make up 8% of buildings; the remaining 3% include castles and other structures. More than 90% of the buildings are made of wood and 13% of the buildings are privately owned. About a third of the national treasures in the two categories of “handicrafts” and “paintings” are written cultural assets such as documents, letters or books. The categories “swords”, “paintings”, “sculptures” and “other handicrafts” each comprise 15% of the national treasures.

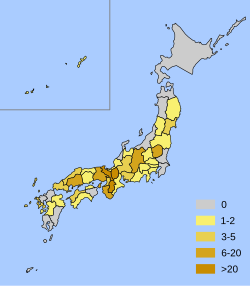

Geographical distribution

The geographical distribution of the national treasures in Japan is very inhomogeneous. In more remote parts of the country, such as Hokkaidō and Kyūshū, there are only a few national treasures, in the two prefectures of Miyazaki and Tokushima none at all.

In four prefectures of the Kansai region there are more than 10 national treasures each in the category structures and buildings: 11 in Hyogo prefecture , 48 in Kyoto prefecture , 64 in Nara prefecture and 22 in Shiga prefecture . Taken together, they have 145 or 67.5% of the monuments. Ninety monuments alone are located in just three places: in Kyoto , the capital and imperial seat for more than 1000 years, in the Hōryū-ji temple , which was founded by Prince Shōtoku around 600 , and in Nara , capital of Japan from 710 to 784.

The national treasures of the second category, arts and crafts, are geographically similarly distributed as the architectural monuments: the largest number is in the Kansai region and here 481 or 55.5% of the national treasures in the seven coastal regions. The Tokyo Prefecture , in which there are only two architectural monuments, has 205 cultural assets, an extremely high number of handicrafts and artistic national treasures. Of these, 87 can be seen in the Tokyo National Museum.

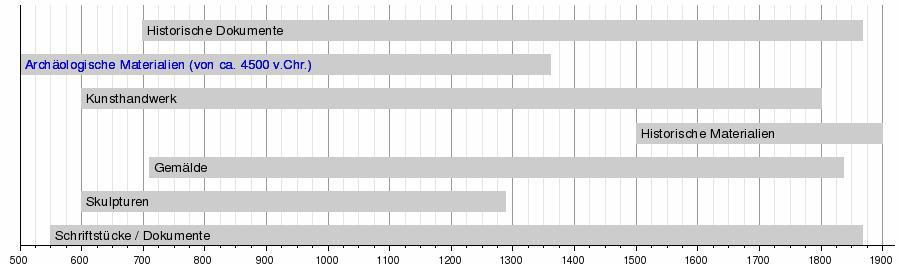

Age

From the national archaeological treasures dating back 4,000 years to the Akasaka Palace in the early 20th century, the national treasures provide an overview of the history of Japanese art and architecture from ancient times to modern times . The pieces of each individual category of the national treasures may not represent an entire period of time, but rather they stand for certain moments that are shaped by historical events, and they are exemplary of typical artistry or an architectural style of that period.

The national treasures in the temple subcategory date from the late 7th century, 150 years after Buddhism came to Japan (6th century), and they extend into the late 19th century, the end of the Edo period and the Beginning of the modern age. The history of the Shinto shrines in Japan, on the other hand, is older than that of the Buddhist temples, but due to the custom of renewing them at regular intervals ( 式 年 遷 宮 祭 , Shikinen sengū-sai ), the shrines only go back to the 12th century back. The archetype of a Japanese castle comes from a period of about 50 years, which began with the construction of Azuchi Castle in 1576 and which is characterized by a change in the function and style of castles. This period ended in 1620 when the Tokugawa shogunate prevailed over the Toyotomi clan in 1615 and subsequently prohibited the building of new castles.

The earliest evidence of civilization in Japan dates back to the Jōmon period , from around 10,000 BC. Until 300 BC Terracotta figurines ( dogū ) and some of the world's oldest ceramic finds discovered in northern Japan can be found as the oldest national treasures in the “archaeological materials” category. Some of the most recent pieces in this category are objects made from sutras ( 経 塚 , Kyōzuka ) from the Kamakura period.

The age of the national treasures in the arts and crafts, documents and sculptures categories is directly related to the introduction of Buddhism to Japan, 552. Some of the oldest national treasures in these categories were brought to Japan directly from China and Korea. Japanese sculptures, which were mainly of a religious character, fell into disrepair after the Kamakura period, which is why there are no national treasures younger than the Kamakura period in the “Sculptures” category.

See also

literature

- William Howard Coaldrake: Architecture and Authority in Japan (= Nissan Institute / Routledge ja studies ). Routledge , London / New York 1996, ISBN 0-415-05754-X ( limited preview in Google book search).

- William Howard Coaldrake: Architecture and Authority in Japan . Routledge, London / New York 2002, ISBN 0-415-05754-X ( limited preview in Google book search).

- William E. Deal: Handbook to Life in Medieval and Early Modern Japan . Oxford University Press, New York 2007, ISBN 0-19-533126-5 , pp. 415 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- Walter Edwards, Jennifer Ellen: A companion to the anthropology of Japan (= Blackwell Companions to Social and Cultural Anthropology ). Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford 2005, ISBN 0-631-22955-8 , pp. 36–49 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- Siegfried RCT Enders, Niels Gutschow: Hozon: Architectural and Urban Conservation in Japan . Edition Axel Menges, Stuttgart / London 1998, ISBN 3-930698-98-6 , pp. 207 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- Kate Fitz Gibbon: Who Owns the Past? Cultural Policy, Cultural Property, and the Law . Ed .: Kate Fitz Gibbon (= Rutgers Series on the public life of the arts ). Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, N.J. 2005, ISBN 0-8135-3687-1 , pp. 362 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- Junko Habu: Ancient Jomon of Japan (= Case Studies in Early Societies . Volume 4 ). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK / New York 2004, ISBN 0-521-77670-8 , pp. 332 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- Money L. Hickman: Japan's Golden Age: Momoyama . Yale University Press, New Haven 2002, ISBN 0-300-09407-8 , pp. 320 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- Jukka Jokilehto: A History of Architectural Conservation (= Butterworth-Heinemann Series in Conservation and Museology, Conservation and Museology Series ). Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford 2002, ISBN 0-7506-5511-9 , pp. 368 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- Hideto Kishida: Japanese Architecture . Read Books, New York 2008, ISBN 1-4437-7281-X , pp. 136 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- Ryūji Kuroda: Encyclopedia of Shinto - History and Typology of Shrine Architecture . Ed .: Kokugakuin University . β1.3, June 2, 2005 ( online ).

- Brian J. McVeigh: Nationalisms of Japan: Managing and Mystifying Identity . Rowman & Littlefield, Lanham, Md. 2004, ISBN 0-7425-2455-8 , pp. 333 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- Hugo Münsterberg: The Arts of Japan: An Illustrated History . CE Tuttle Co., University of Michigan 1957, p. 201 .

- Kazuo Nishi, Kazuo Hozumi: What is Japanese Architecture? Kodansha International, Tokyo / New York 1996, ISBN 4-7700-1992-0 , pp. 144 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- Kouzou Ogawa, Nobuko Seki, Takayuki Yamazaki: Buddhist Images (= 山溪 カ ラ ー 名 鑑 ). 山 と 溪谷 社 (Yama to Keikokusha), 2009, ISBN 978-4-635-09031-5 , pp. 771 ( limited preview in Google Book Search - Japanese: 仏 像 .).

- George Sansom, Sir George Bailey Sansom: A History of Japan to 1334 (= A History of Japan, Sir George Bailey Sansom, Stanford studies in the Civilizations of Eastern Asia . Volume 1 ). Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA 1958, ISBN 0-8047-0523-2 , pp. 512 ( limited preview in Google Book Search).

- Peter Dennis, Stephen Turnbull: Japanese Castles 1540-1640 (= Fortress Series . Volume 5 ). Osprey Publishing, Oxford 2003, ISBN 1-84176-429-9 , pp. 64 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- Kanehiko Yoshida, Hiroshi Tsukishima, Harumichi Ishizuka, Masayuki Tsukimoto: Kuntengo Jiten . Tōkyōdō Shuppan, Tokyo 2001, ISBN 4-490-10570-3 , pp. 318 ( limited preview in Google Book Search - Japanese: 訓 点 語 辞典 .).

- David Young, Michiko Young: The Art of Japanese Architecture (= Architecture and Interior Design ). Tuttle Publishing, Tokyo / Rutland, Vt. 2007, ISBN 0-8048-3838-0 , pp. 176 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

Web links

Remarks

- ↑ The nominal number of damaged cultural assets is 704, since some of these cultural assets are mentioned several times, this results in a mathematical figure of 714. These include five national treasures and, for example, the pine islands near Matsushima , which are among the three most beautiful landscapes in Japan .

- ↑ This applies primarily to works from the early days, such as houses, public buildings, bridges, dams, fences and towers, which are threatened by land development and cultural changes. The registration is a means of avoiding the destruction of such structures without the need to determine their cultural value. The measures for protection are moderate and only include registration, inspection and suggestions. As of April 1, 2009 there were 7407 registered structures.

- ↑ It is usually difficult to obtain consent for state property and private companies.

- ↑ These indirect measures were added as an amendment to the 1950 Act .

- ↑ The head of the Office for Cultural Affairs only has the authority to recommend repairs in the case of “important cultural property” .

- ↑ A gold-plated bronze tableware from Saitobaru- Kofun in Miyazaki Prefecture was declared a national treasure. However, it is currently in the Gotō Art Museum ( 五 島 美術館 , Gotō Bijutsukan ) in Tokyo.

Individual evidence

- ↑ 文化 財 保護 法 . (No longer available online.) In: 電子 政府 の 総 合 窓 口 (e-Gov) . 総 務 省 行政 管理局 (Ministry of Public Administration, Interior, Post and Telecommunications), May 2, 2011, archived from the original on February 26 2012 ; Retrieved January 30, 2012 (Japanese).

- ↑ LASDEC - 地方自治 情報 セ ン タ ー (Local Authorities Development Center). (No longer available online.) Nippon-Net, archived from the original on February 14, 2014 ; Retrieved January 30, 2012 (Japanese).

- ^ A b Intangible Cultural Heritage - Protection system for intangible cultural heritage in Japan. (PDF; 35.8 MB) (No longer available online.) Office for Cultural Affairs , 2009, archived from the original on May 24, 2011 ; accessed on January 24, 2012 (English).

- ↑ a b Kate Fitz Gibbon: Japan's protection of his cultural heritage - a model . In: Who owns the past? Cultural policy, cultural property, and the law . Rutgers University Press, 2005, pp. 331 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Jukka Jokilehto: A history of architectural conservation . Ed .: Butterworth-Heinemann. 2002, p. 279 (English).

- ^ A b c d Walter Edwards: Japanese Archeology and Cultural Properties Management - Prewar Ideology and postwar Legacies . In: Jennifer Ellen Robertson (Ed.): A companion to the anthropology of Japan . John Wiley & Sons, 2005, pp. 39 ( limited preview in Google Book Search - English).

- ^ A b c William Howard Coaldrake: Architecture and Authority in Japan . Routledge , London / New York 1996, ISBN 0-415-05754-X , pp. 248 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ 文化 財 保護 の 発 展 と 流 れ . asahi.net, accessed January 30, 2012 (Japanese).

- ↑ a b c Wimonrart Issarathumnoon: The community development bottom-up approach to conservation of historic communities: lessons for Thailand. (PDF; 453 kB) (No longer available online.) In: The Nippon Foundation. Urban Design Lab, University of Tokyo , 2004, archived from the original on October 25, 2012 ; accessed on January 30, 2012 (English).

- ↑ 古 社 寺 保存 法 (明治 30 年 法律 第 49 号) . In: 古 社 寺 保存 法 . Nakano Bunko (The Nakano Library) , 2008, accessed January 30, 2012 (Japanese).

- ↑ a b c d Alexander Mackay-Smith: Mission to preserve and protect . In: Japan Times . Tokyo April 29, 2000 ( online [accessed January 22, 2012]).

- ↑ 史蹟 名勝 天然 紀念物 保存 法 . In: 縄 文学 研究室 (The Jomonology Research Laboratory). Nakamura Kousaku, accessed January 30, 2012 (Japanese, including implementing regulations).

- ^ Advisory Body Evaluation Himeji-jo. (PDF; 1.2 MB) UNESCO , October 1, 1992, accessed December 16, 2009 .

- ↑ a b 金堂 . (No longer available online.) Hōryū-ji , archived from the original on January 11, 2010 ; accessed on January 30, 2012 (Japanese, including illustration and interactive map).

- ↑ a b 五 重 塔 . (No longer available online.) Hōryū-ji , archived from the original on January 11, 2010 ; accessed on January 30, 2012 (Japanese, including illustration and interactive map).

- ↑ a b c d Cultural Properties for Future Generations. (PDF; 1.1 MB) (No longer available online.) Office for Cultural Affairs, March 2011, archived from the original on August 13, 2011 ; Retrieved January 25, 2012 .

- ^ A b Nobuko Inaba: Policy and System of Urban / Territorial Conservation in Japan. (No longer available online.) National Research Institute of Cultural Properties, 1998, archived from the original on October 5, 2009 ; accessed on January 30, 2012 (English).

- ^ Damages to Cultural Properties in the "the Great East Japan Earthquake". (PDF) (No longer available online.) Office for Cultural Affairs, July 29, 2011, archived from the original on August 13, 2011 ; accessed on January 30, 2012 (English).

- ↑ Kate Fitz Gibbon: Japan's protection of his cultural heritage - a model . In: Who owns the past? Cultural policy, cultural property, and the law . Rutgers University Press, 2005, pp. 333 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x 国 指定 文化 財 デ ー タ ベ ー ス . In: Database of National Cultural Properties. Office for Cultural Affairs , November 1, 2008, accessed December 15, 2009 (Japanese).

- ↑ Peter Dennis, Stephen Turnbull: Japanese Castles 1540-1640 (= Fortress Series . Volume 5 ). Osprey Publishing, Oxford 2003, pp. 52 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ A b William E. Deal: Handbook to Life in Medieval and Early Modern Japan . Oxford University Press, New York 2007, pp. 315 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Peter Dennis, Stephen Turnbull: Japanese Castles 1540-1640 . Oxford 2003, p. 21 .

- ↑ William Howard Coaldrake: Architecture and Authority in Japan (= Nissan Institute / Routledge yes studies ). Routledge , London / New York 1996, ISBN 0-415-05754-X , pp. 105–106 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ a b State Guest Houses. (No longer available online.) Cabinet Office Government of Japan, archived from the original on July 10, 2012 ; Retrieved December 1, 2009 .

- ^ Jaanus architecture database

- ^ Hideto Kishida: Japanese Architecture . Read Books, New York 2008, pp. 33 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Kazuo Nishi, Kazuo Hozumi: What is Japanese Architecture? Kodansha International, Tokyo / New York 1996, p. 41 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Ryūji Kuroda: Encyclopedia of Shinto - History and Typology of Shrine Architecture . Ed .: Kokugakuin University . β1.3, June 2, 2005 ( online ).

- ↑ Nomination File - UNESCO ( Memento from October 25, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ 大 仏 殿 (Great Buddha Hall). Tōdai-ji , accessed November 23, 2009 (Japanese).

- ↑ 北 能 舞台 (Northern No-Stage). (No longer available online.) Nishi Hongan-ji, archived from the original on April 6, 2009 ; Retrieved November 14, 2009 (Japanese).

- ^ Jaanus architecture database

- ↑ History of the Shizutani School. Bizen , accessed January 29, 2012 .

- ^ Oura Catholic Church. Nagasaki Tourism Internet Committee, accessed November 14, 2009 .

- ↑ 額 田 寺 伽藍 並 条 里 図 (Map of the Nukata-dera Garan and the surrounding area). (No longer available online.) National Museum of Japanese History, archived from the original on February 12, 2009 ; Retrieved January 30, 2012 (Japanese).

- ↑ a b 那 須 国 造 碑 (Stone of Nasu). (No longer available online.) Ōtawara Tourist Association, archived from the original on June 13, 2011 ; Retrieved January 30, 2012 (Japanese).

- ↑ The University of Tokyo Library System Bulletin Vol 42, No 4. (PDF; 1.3 MB) (No longer available online.) Tokyo University Library, September 2003, archived from the original on June 5, 2011 ; Retrieved January 30, 2012 (Japanese).

- ↑ 教育 ほ っ か い ど う 第 374 号 - 活動 レ ポ ー ト - 国宝 「土 偶」 に つ い て (Education Hokkaidō issue 374 activity report, National Treasure dogū). (No longer available online.) Hokkaido Prefecture Government, 2006, archived from original on May 5, 2008 ; Retrieved May 13, 2009 (Japanese).

- ↑ 合掌 土 偶 に つ い て - 八 戸 市 (Gasshō dogū - Hachinohe). Hachinohe , 2009, accessed January 30, 2012 (Japanese).

- ↑ 普 済 寺 (Fusai-ji). (No longer available online.) Tachikawa Tourist Office, archived from the original on December 8, 2007 ; Retrieved January 30, 2012 .

- ↑ 日 高 村 文化 財 国宝 (Hidaka Cultural Properties, National Treasure). (No longer available online.) Hidaka , archived from the original on July 19, 2011 ; Retrieved June 4, 2009 .

- ↑ Kōkan Nagayama: The Connoisseur's Book of ja Swords . Ed .: Kodansha International. Tokyo; New York 1998, ISBN 4-7700-2071-6 , pp. 13 ( online ).

- ↑ 広 島 県 の 文化 財 - 梨子 地 桐 文 螺 鈿 腰刀 (Cultural Properties of Hiroshima Prefecture - nashijikirimon raden koshigatana). (No longer available online.) Hiroshima Prefecture , archived from original on Nov. 28, 2009 ; Retrieved September 29, 2009 .

- ↑ Writing box with eight bridges. In: Emuseum. Tokyo National Museum . Retrieved August 27, 2009 .

- ↑ 沃 懸 地 杏 葉 螺 鈿 平 や な ぐ い か ま く ら (Quiver). (No longer available online.) Kamakura , archived from the original on July 22, 2011 ; Retrieved May 22, 2009 (Japanese).

- ↑ 沃 懸 地 杏 葉 螺 鈿 太 刀 か ま く ら (Long sword). (No longer available online.) Kamakura, archived from the original on July 22, 2011 ; Retrieved May 22, 2009 (Japanese).

- ↑ 厳 島 神社 古 神 宝 類 (Old sacred treasures of Itsukushima Shrine). (No longer available online.) Hiroshima Prefecture , archived from the original on July 19, 2011 ; Retrieved September 10, 2009 .

- ↑ 本 宮 御 料 古 神 宝 類 (Old sacred treasures). Kasuga-Taisha , accessed September 10, 2009 .

- ↑ 琉球 国王 尚 家 関係 資料 (Materials of the Shō family - Kings of Ryūkyū). (No longer available online.) Naha, Okinawa, February 20, 2004, archived from the original October 6, 2011 ; Retrieved December 12, 2009 .

- ↑ 慶 長 遣 欧 使節 関係 資料 (Materials of the Keichō Embassy to Europe). (No longer available online.) Miyagi Prefecture , February 20, 2004, archived from original on May 12, 2011 ; Retrieved December 12, 2009 .

- ↑ 伊 能 忠 敬 記念 館 (Inō Tadataka Museum). (No longer available online.) Inō Tadataka Museum, archived from the original on December 8, 2010 ; Retrieved July 2, 2010 .

- ↑ Tokyo National Museum (ed.): Ise Jingu and Treasures of Shinto . 2009.

- ↑ 仏 教 索引 (Buddhism index). janis, accessed June 14, 2009 (Japanese).

- ↑ James M. Goodwin, Janet R. Goodwin: The Usuki Site. (No longer available online.) University of California , archived from the original on December 3, 2008 ; Retrieved November 17, 2014 .

- ↑ Christine Guth Kanda: Shinzō . Ed .: Harvard Univ Asia Center. Cambridge MA 1985, ISBN 0-674-80650-6 , pp. 81-85 ( online [accessed June 13, 2009]).

- ↑ Jaanus architecture database

- ^ Foundations for Cultural Administration. (PDF; 464 kB) (No longer available online.) In: Administration of Cultural Affairs in Japan - Fiscal 2010. Bunka-chō , 2004, archived from the original on April 9, 2011 ; Retrieved November 4, 2010 .

- ↑ Frequently asked questions about the Tokyo National Museum. Tokyo National Museum , Retrieved May 8, 2011 .

- ^ National Treasure designation. (No longer available online.) Tōkamachi Museum , archived from the original on July 21, 2011 ; Retrieved May 15, 2009 (Japanese).

- ^ Special Exhibition - The Legacy of Fujiwara no Michinaga: Courtly Splendor and Pure Land Faith. (No longer available online.) Kyoto National Museum, archived from the original on November 29, 2007 ; Retrieved May 15, 2009 .