Russia reporting in Germany

Reporting on Russia in Germany began with the resumption of regulated diplomatic contacts in the 16th century. Today, Russia reporting in Germany is carried out by over 40 correspondents , mainly from the Russian capital Moscow . Germans are more interested in Russia than anywhere else in the world. To this day, stereotypes persist in reporting on Russia.

history

First phase

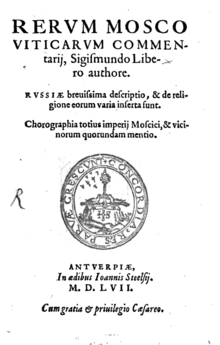

The Mongol invasion of the Rus from 1237 to 1240 cut off all ties between the Russians and the West for 200 years . Only Northeast Russia remained open to Western European contacts and influences through trade in the Baltic Sea with the Hansa , so that there are hardly any Western reports about the Russian countries during this period. One of the first German reporters was Johannes Schiltberger , the “German Marco Polo”, who described the Rus in a concise and stylistically undemanding manner. His travel book was printed in the second half of the 15th century. His news aroused great interest among his contemporaries. Yet knowledge of the country remained fragmentary. The Schedel'sche Weltchronik of 1493 reported "The Reussen hit the Lithuanians with a grossly unskilled people." When the Rus were able to free themselves from the tributary rule of the Tatars towards the end of the 15th century, the rulers of the Holy Roman Empire sent inside envoy to Russia with political instructions for a few years. The first widespread reports of this time come from the works of Johann Fabris and Paolo Giovio from 1525, translated into German. In them Moscow Russia was the main theme for the first time. Both writings served Western Europeans as the most accessible sources on the newly discovered country until the middle of the 16th century, which the authors mentioned presented in an advantageous and somewhat idealized light. Giovio and Fabri perceived Moscow Russia as a potential ally and described it as a force to which one could turn for help in the fight against external and internal dangers - especially against the Ottoman conquest and Protestantism. The first German report on Russia in modern times comes from Sigismund von Herberstein , who traveled to Poland and the Moscow Empire twice in the service of the Habsburg Crown (1516–1518 and 1526/27). Herberstein, on the other hand, preferred the Polish-Lithuanian Empire , Russia's adversary at the time, and sought to question and mock the image drawn by his predecessors in publications of the 1520s to 1540s. His report Rerum moscoviticarum commentarii determined the Germans' image of Russia for a long time. His book was a great success and by 1600 there had been a total of 20 editions, seven of them in German. These pioneering works, written up to 1550, laid the groundwork for further reporting.

Although the mentioned works appeared in many editions in the 16th century, it was only the Russian writings of the second half of the 16th century that conveyed news about the Moscow state to a wider public. At that time there were no modern periodical newspapers in the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation , but an early form of the press, the pamphlets or "New Newspapers", had fully developed. The books on Russia of that time appeared far from the events and only reached a small audience, while the leaflets reached a relatively large number of readers, but quickly became outdated and forgotten. In the second half of the 16th century around 100 publications appeared in print dealing with the Livonian War and Ivan IV's domestic policy . The reporters such as B. Heinrich von Staden provided valuable insights into the time of the Oprichnina . The books on Russia and the German leaflets were initiated by the warring neighbors Livonia and Poland-Lithuania . The aim was not to paint a complete and balanced picture of the Moscow state, but to represent Russia on behalf of the Holy Roman Empire in the light of its opponents Livonia and Poland-Lithuania. The pamphlets describe in particular the armies, the armament and the horrors of war of the Tatars in Russian service , which emphasized the barbaric, Asian nature of the Russians. "The Russian" is characterized as a clever, faithless and contract-breaking politician. In addition to this negative assessment, the respect for the military power of the Russians emerges again and again. All in all, the German pamphlets are covered with extreme slogans against the unknown Russians, while the Polish originals used a much more moderate expression because they could not use the same cliché ideas for the Russians better known to them.

The contempt for the autocratic form of rule also determined the reports on Russia from the second half of the 16th century. The then Tsar Ivan IV was described as proud, insidious, suspicious, irascible and cruel. Through the detailed description of its numerous acts of violence, the Moscow autocracy was characterized as tyrannical arbitrariness. On the other hand, Ivan IV's early reform period was hardly included in the reports. Economy, law and society were hardly discussed; on the other hand, the Orthodox religion aroused interest in Germany, which was marked by religious struggles. Similar to the ruler, the people were given mostly negative traits. The Russians appeared as crude, uneducated barbarians, as cruel and immoral drunkards. Their frugality, piety, patience and obedience, however, were presented as positive.

Pre-Petrine phase

With the end of the Livonian War, the first phase of intensive German Russia journalism also ended. The number of eyewitnesses declined due to the ensuing domestic political chaos in Russia and the Thirty Years' War that broke out in Germany as a result. While there were 35 books on Russia up to 1613, only three new editions were added between 1613 and 1689. The numerous new editions of older reports and the small number of new publications confirmed the predefined patterns that from then on determined the image of Russia. The Russia reports from the time of turmoil brought a range of new information, but no change in the negative presentation.

Outstanding at this time is Adam Olearius' travelogue published in 1647 . The scholar accompanied the embassy of Duke Friedrich III. from Holstein via Moscow to Persia (1633–1635 and 1635–1639). The book became a bestseller . In addition to five German editions, five Dutch, four French, three English and one Italian editions were published. Even in the first third of the 18th century, the success continued with four more French editions. The Protestant Olearius drew a very multifaceted picture of Russia, but when describing the strict demarcation between foreigners and native Russians, he returned to the familiar negative stereotypes. He described the reprehensible character of the Russians, their immoral behavior and their lack of knowledge of scientific and religious questions. The few positive character traits were immediately put into perspective in his work. The wide dissemination of the work strengthened the negative image of Russia that had existed since the Livonian War.

The books on Russia in turn served as a template for the works of national studies conceived as textbooks and manuals. These writings were intended for universities, grammar schools and knight academies and reached an even wider audience. Among the numerous editions, the Oribs politicus by Georgius Hornius from 1667 stood out, which achieved several dozen new editions in the following decades. In the work Russia is described as a state that has little in common with Europe in terms of its structure. The Russians are seen as enslaved and uneducated servants.

The poor reporting and the general Russian tenor were corrected in the second half of the 17th century by the increasingly strong newspaper medium . Germany was regarded as the leading newspaper country, 50 to 60 German-language newspapers were also competing for readership with an average circulation of 350 to 450 copies per newspaper per week. The upcoming Europeanization of Russia in the time of pre-Petrine Russia was covered in more than 9500 newspaper reports. Tsar Alexei I , in particular , was initially described as aloof, then with respect, and finally with obvious sympathy during his 31-year rule. Since the 1660s, Russia was also connected to the European postal network, so that more and more correspondence from Moscow found its way into the German press.

Petrinian era

Due to the increased public interest in Germany during the Petrine epoch in Russia, the newspapers in Germany met the increased need for information and granted the phenomenon Russia a wider area in reporting. The newspapers reported on the change in Russia from an Asian despotism to a modern absolutist state. The newspaper writers were ready to accept a Russia converging with Western Europe and reported accordingly positively about the changes. The Russian folk character continued to be depicted as a slave nature, alcoholic and wild.

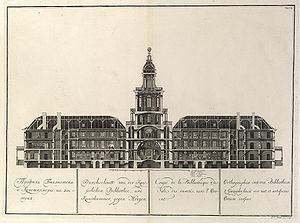

Western foreigners in Russian service who supported the reform efforts acted as carriers of this reporting. In contrast to the diplomats who previously acted as Russia reporters, they were much more familiar with the country and its people through their long stays. The residents of the German suburb of Nemezkaja Sloboda delivered regular news about Russia to the German-speaking area from here. Because Peter I often visited the German suburbs for foreigners in his youth and established contacts, he received positive reports from the start. Each of his actions met with a strong journalistic response. In particular, Peter's court life, which was not limited by any protocol, was described. Accordingly, ideas about the country and its inhabitants in Germany expanded.

Around 1700, the residents of the German-speaking area had access to current reports on the modernization and changes in the Russian Empire. At the same time, the older Russian books were still being used, and were being reissued over and over again. The reason for this is the limitation of the newspaper medium, which could only describe a small daily excerpt, while the books on Russia were supposed to give an all-encompassing timeless view of the empire. This resulted in a very great contrast in the reporting in the image of Russia, which ranged from an archaic, barbaric to a modern western image of Russia. In the war that followed, the military constellation led to one-sided reporting. After the outbreak of the Great Northern War, and especially in the first few years, German readers could learn little from the Russian side, as the Russian enemy effectively blocked the flow of news from Moscow. At the same time, the Swedes for their part knew how to fake reports and bring them into the German newspapers that depicted the barbaric cruelty of the Russians. The Russians were portrayed as troublemakers who alone decide when there will be peace in the north. The fear of the vastness and the immeasurable resources of the land dominated. This was done with the intention of intimidating the newspaper readers and turning them against the Russians. The Swedes also tried to create an anti-Russian mood through diatribes. Peter I recognized the importance of newspapers as an opinion-forming medium and entrusted Heinrich von Huyssen with using counter-propaganda to make the Swedish polemics ineffective. Through his close acquaintance with the Leipzig family of scholars Mencke , he was able to achieve far-reaching influence. The monograph Relation before the present formation of the Moscowite Empire , which he published under a pseudonym, marked the beginning of a new assessment of Russia. From now on, the Russia Books pursued the goal of conveying current information and images of Russia.

Time of enlightenment

A new section of Russia's reporting began with the writing of the Hanoverian diplomat Friedrich Christian Weber , Das verierter Russland , which appeared in Frankfurt in 1721. His description is varied and very precise and had an influence on German journalism on Russia until the 1760s. As with the older books on Russia, a negative canon of values is still attached to the Russians, but there are also a number of positive characteristics that are seen in relation to Peter I, who "made people out of a herd of unreasonable animals". Through his consistent designation of the people as Russians and the empire as Russia, his publication helped to displace the designation Muscovites or Muscovites , which is common in Russia reporting , which had already acquired a negative connotation.

This drawn both positive and negative coverage continued into the 1740s. An article in the Zedlers Universal Lexicon from this time commented on this as follows:

“The glorious arrangements of Tsar Peter I, as well as his successors and the trips made by the Russians to neighboring European countries, both as a multitude of foreigners who were gradually called there, caused this nation a complete change [...] and the manner set up to live according to the rest of European nations customs.

Otherwise, this nation will be blamed for being suspicious, haughty, treacherous, stubborn, and cruel by nature. You showed great cunning in trade and business, but considered it an honor if you could betray someone. In addition, they are adept at learning all sciences, tireless and attentive, of which they have so far passed many tests with astonishment all over the world, although most of them can be ascribed to Tsar Peter I, who, through an astonishing patience and zeal, instructed this inexperienced nation undertook and carried out happily. "

The interest of German enlighteners in Russia and its cultural life led to more and more reports in magazines or one-off publications in the further course. The number of reports fluctuated during the wars, before and after the many palace revolutions of that time, and much more was published. The many Germans who now immigrated to Russia changed the tenor of Russia reporting considerably, it became more differentiated. The new generation of reporters were now part of the action in Russia, taking sides for or against the country. There was almost unreserved optimism among the country's friends who saw Russia as an ally. In the tenor, August Ludwig von Schlözer published the title The Newly Changed Russia in 1769 , alluding to Weber's 1721 edition. On the other hand, Russia's opponents tried to portray the country as a potential enemy and painted a hideous, gloomy and despicable picture from Russia.

For the magazines of the 1780s and 1790s, Russia was already an integral part of Europe, albeit still strange and strange to some authors. This is how Schubert, Wieland and the Berlin Enlightenment team felt . Schiller and Goethe felt the same way . The colorful palette of images that appeared in reports on Russia at the end of the 18th century ranged from distortions filled with hate and fear to enthusiastic praise. This range was best conveyed by the literary contemporaries Joseph von Görres and August von Kotzebue .

During and after the French Revolution

In the course of the French Revolution , the era of the nation states, the national freedom movements but also the chauvinistic mass psychoses began . The events in France sparked fears and worries in the German states. But although Russia appeared to be the greatest opponent of the French Empire , liberal and democratic -minded publicists were mostly anti-Russian. As early as 1791 a book directed against Russia appeared in Leipzig, which was written by the Swedish King Gustav III. was written. In it he claims that aggressive Russian despotism is also directed against German freedom. Even Ernst Ludwig Posselt , Georg Friedrich Rebmann and Joseph von Gorres railed against the Russian Empire as the stronghold of despotism. In his European Annals of 1796, Posselt paints the picture of a colossus, which “in a terrible mixture pairs the strength of wildness with all the arts of the Enlightenment”. For Rebmann, in his work The Latest Gray Monster from 1797, Russia is “an Asian power whose multitudes are the Huns of our time.” In his edition “Red Leaf”, Görres panicked at the “colossus of snow, ice and blood kneaded together "And" held together from knuckle and terror ". In contrast, other conservative patriots believed that only Russia could save the German states from the French hordes. With this in mind, Karl Wilhelm von Byern wrote his brochure What can one expect from Russia in the current critical circumstances for the benefit of mankind.

Even Ernst Moritz Arndt , bedeutendster poet of the era of the War of Liberation published in 1805 in the Nordic Controlleur a Russian article. Like the others mentioned above, he judged from the level of self-confident half-knowledge:

“The Russians have been very unhappy in the way they have received that little bit of culture that they are allowed to receive. The beginning of Russian culture and refinement struck the poor people in the deepest dung of slavery , they still stand in it and although the crowd and power have grown, although large cities and fortresses and ports have been built, no bourgeois class, no civic spirit has in the unfortunate country until want to thrive now. Slave air still blows over the vast empire and servile laziness and carelessness does not allow the nobler above or below to flourish. "

After Arndt went to Russia himself in 1812 and was able to get an idea on site, he regretted his views at the time. Other famous freedom fighters, too, were often led to misperceptions out of their class consciousness. In addition to these very negative and, in many cases, excessively exaggerated reports, there were also reporters in Russia who conveyed a positive image characterized by understanding and sympathy. A well-known representative was Johann Gottfried Richter . Richter raved about the Russia enthusiasts the most. But even serious and soberly reflective journalists were favorable to Russia and saw Russia as a powerful state.

The defeat of Napoleon's Grande Armée in Russia in 1812 triggered a flood of journalistic and poetic commitments to Russia. German journalists and poets celebrated the self-sacrifice of Moscow, the Russian soldiers and the Russian people.

Time of the Holy Alliance

The hopes of the liberals and patriots were disappointed by the restoration policy in the course of the Congress of Vienna . Austria, Prussia and Russia formed a holy alliance that was supposed to secure the political situation. The increasing police violence and poor harvests cause bitterness and anger among the poor and the citizens of the German Confederation . Old images of the enemy were revived and new ones discovered. It was said that the Russian emperor and the Jews were to blame for everything. Russian troops protected the German princes while the Jews received civil rights through Napoleon and were henceforth equal.

From the Seven Years' War to the First World War

Since the middle of the 18th century, Russia was at the center of Prussian and later German foreign policy. This point in time also marks the beginning of Russian influence on domestic political debates in Germany.

Relations between Russia and Prussia in the 18th century, the participation of the Germans in Napoleon's campaign against the Russian Empire in 1812 and the two world wars in the 20th century led to a contradicting view of Russia in Germany. On the one hand, the German soldiers and civilians were able to gain a more differentiated view of the Russian people in the war. It was the helpful, “naive”, “religious”, “clever”, “brave”, “extremely poor”, “loyal to the state” but “fatalistic” Russian farmers and residents of Moscow with whom the German soldiers came into contact in 1812. On the other hand, Russia's support for the Prussian monarchy has turned the liberal bourgeoisie in Germany against Russia. However, Russia's geographic size, the unique mentality of the people and the rich culture have fascinated all viewers in Germany.

Soviet Union time

In the Third Reich , reporting on Russia was decisively shaped by National Socialist ideology . The fight against “ Jewish Bolshevism ” and the efforts of the National Socialists to substantiate their claims of race theory in the eyes of the population turned reporting on Russia into a propaganda spectacle during the Nazi era that emphasized the “primitiveness” of the Russian way of life and was often artificial hyped. Documentations of the Nazi newsreel or the Berlin exhibition “ The Soviet Paradise ” from 1942 are characteristic of this.

During the Cold War epoch in the Federal Republic, among others, Klaus Bednarz (1977–1982), Rudolph Chimelli (1972–1977), Mario Dederichs (1984–1988), Johannes Grotzky (1983–1989), Joachim Holtz (1984–1990) ), Norbert Kuchinke (1973–1984), Fritz Pleitgen (1970–1977), Hermann Pörzgen (1956–1976), Gerd Ruge (1956–1959, 1978–1981, 1987–1993), Gabriele Krone-Schmalz (1987–1991 ) and Leo Wieland (1977–1984).

Post-Soviet Russia

Russia correspondents in the epoch around the turn of the millennium a. a. Klaus Bednarz , Golineh Atai , Anja Bröker , Katja Gloger , Ulrich Heyden , Christiane Hoffmann , Udo Lielischkies , Lothar Loewe , Sonia Mikich , Boris Reitschuster , Thomas Roth , Ina Ruck , Dirk Sager , Thomas Urban and Markus Wehner .

In reporting on Russia from the 1990s to 2000, according to a working paper by the Eastern European Institute at the Free University of Berlin, there was a tendency to convey “stereotypical” images, caused by negative news factors. According to the online newspaper Russland.ru , the image of poverty and chaos and the contrasting portrayal of the super-rich oligarchic caste prevailed in the 1990s, which survived until the turn of the millennium as the image of Russia in the minds of "Russia-inexperienced Germans". Later, after Russia's economic recovery, when evidence for this picture was hard to find on site, the focus of the reporting shifted to Russia's deficits in freedom of expression and its attribution to the politics of the Kremlin. According to the Eastern Europe analyst Alexander Rahr , the negative image of Kremlin policy since the turn of the millennium differed from the policy of the Russian leadership of the 1990s, which was viewed much less critically. While the German-language media reinforced the negative image of Russia, independent research on Eastern Europe had largely been scaled back.

By Mikhail Gorbachev was criticized in 2000 by Russia coverage in Germany was influenced partly or mainly of a negative attitude and lack of sophistication. He later said that there were difficulties and misunderstandings in correspondent work. According to some commentators, the focus on Vladimir Putin and Russia's political crises in the Western media paints a skewed picture of the real situation in Russia.

In the opinion of the online newspaper Russland.news, only the small, western-oriented part of the opposition is represented positively . In the Georgian war , German journalists reported almost exclusively on the Georgian side and resorted to images of the enemy from the Cold War.

German-speaking critics of the reporting, such as the online newspaper russland.NEWS, Gabriele Krone-Schmalz and Alexander Rahr, mention the lack of regional knowledge of many German reporters on Russia and the trend towards confirmation of negative clichés in German-speaking countries through such news. In contrast, there are hardly any positive reports in the major media.

To “correct” Russia's reputation, President Putin founded the media holding Russia Today in December 2013 “to improve the efficiency of the public media” and to convey a “positive image of Russia”. The conglomerate was soon referred to as the modern "propaganda machine" or something similar.

In the course of and as a result of the Crimean crisis and the conflict in eastern Ukraine , reports about Russia were increasingly critical. It was also reported that Russian secret services are trying to manipulate public opinion abroad in favor of Russia by means of targeted infiltration by so-called trolls in social networks such as Facebook and in the comment areas of many leading media. Deutsche Welle , Süddeutsche Zeitung , Neue Zürcher Zeitung and many others were affected . As the Süddeutsche reported, "Hundreds of paid manipulators" are in use for this purpose.

Representatives of the Ukraine complained that pro-Russian debaters were massively overrepresented on German television: the evaluation of 30 programs with a classification of “Russia and Ukraine factor” per program only showed a Ukraine factor of at least 50 percent for 7 out of 30 programs. The summary also states: "The restriction of media pluralism in Russia has an impact on German reporting on Russia, in a similarly restrictive manner as in Russia itself."

Web links

- Media analysis of the Eurasian magazine, topic: German Eastern Europe correspondents

- Open letter from the Chairman of the Russian Steering Committee, Mikhail Gorbachev, to the German media, Moscow, March 2008

- Analysis: Whipping boy Putin - an analysis of Gorbachev's open letter

literature

- Klaus-Dieter Altmeppen, Matthias Karmasin: Media and Economy . Volume 2, Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 2004.

- Oldag Caspar, Juri Galperin: Russia image and Russian-German relations in the German media. Working paper of the future workshop of the Petersburg Dialogue, Berlin 2004.

- Wenke Crudopf: Russia stereotypes in German media coverage. 29/2000, working papers of the Eastern European Institute of the Free University of Berlin, Politics and Society, ISSN 1434-419X .

- Lutz Mükke: What else do we know about world events? About the crisis of foreign journalism and the necessary differentiation in the current "quality discussion". no-dossier 2/08.

- Gemma Pörzgen : Interpretation conflict. The Georgia conflict in the German print media. Eastern Europe 58, issue 11 / November 2008.

- Alexander Rahr: Russia steps on the gas: the return of a world power , Carl Hanser Verlag, Munich 2008.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Juri Galperin: German media's image of Russia . Published by the Federal Agency for Civic Education , March 25, 2011.

- ↑ http://www.laender-analysen.de/russland/pdf/Russlandanalysen075.pdf p. 12, accessed on May 17, 2012.

- ^ Mechthild Keller: Russians and Russia from a German perspective . Vol. 2, Munich, p. 33.

- ↑ Ed. By Lew Sinowjewitsch Kopelew and Mechthild Keller: Russians and Russia from a German perspective . Vol. 1, Munich, p. 118.

- ^ Mechthild Keller: Russians and Russia from a German perspective . Vol. 1, Munich, p. 154.

- ^ Mechthild Keller: Russians and Russia from a German perspective . Vol. 1, Munich, p. 173.

- ↑ a b Mechthild Keller: Russians and Russia from a German perspective . Vol. 1, Munich, p. 178.

- ^ Mechthild Keller: Russians and Russia from a German perspective . Vol. 1, Munich, p. 180.

- ^ Mechthild Keller: Russians and Russia from a German perspective . Vol. 1, Munich, p. 267.

- ^ Mechthild Keller: Russians and Russia from a German perspective . Vol. 1, Munich, p. 240.

- ^ Mechthild Keller: Russians and Russia from a German perspective . Vol. 1, Munich, p. 276.

- ^ Mechthild Keller: Russians and Russia from a German perspective . Vol. 2, Munich, p. 138.

- ^ Mechthild Keller: Russians and Russia from a German perspective . Vol. 2, Munich, p. 60.

- ^ Mechthild Keller: Russians and Russia from a German perspective . Vol. 2, Munich, p. 141.

- ^ Mechthild Keller: Russians and Russia from a German perspective . Vol. 2, Munich, p. 79.

- ^ Mechthild Keller: Russians and Russia from a German perspective . Vol. 2, Munich, p. 115.

- ^ Mechthild Keller: Russians and Russia from a German perspective . Vol. 2, Munich, p. 26.

- ^ Mechthild Keller: Russians and Russia from a German perspective . Vol. 2, Munich, p. 29.

- ^ Mechthild Keller: Russians and Russia from a German perspective . Vol. 3, Munich, p. 15.

- ^ Mechthild Keller: Russians and Russia from a German perspective . Vol. 3, Munich, p. 22.

- ^ A b Jahn, Peter: Liberators and semi-Asian hordes. German images of Russia between the Napoleonic Wars and the First World War. In: German-Russian Museum Berlin-Karlshorst eV (Ed.): Our Russians - Our Germans. Pictures from the other 1800 to 2000 . Berlin 2007, pp. 14-29.

- ↑ Wenke Crudopf: Russian stereotypes in German media coverage . Eastern European Institute at the Free University of Berlin, 2000.

- ↑ Interview with Alexander Rahr ( Memento of the original from November 9, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Open letter from Michail Gorbatschow to the German media petersburger-dialog.de ; Wenke Crudopf: Russia stereotypes in German media coverage . Working papers of the Eastern European Institute of the Free University of Berlin. 29/2000 oei.fu-berlin.de (PDF).

- ↑ See z. B. Juliane Inozemtsev: Part of the intoxication. Self-criticism from German Eastern Europe correspondents about the “Orange Revolution” . In: Eurasisches Magazin from July 31, 2008 eurasischesmagazin.de

- ↑ Guest commentary on derstandard.at, accessed on August 11, 2014.

- ^ Nobody can doubt the brutality of Putin's Russia. But the way the Ukraine conflict is covered in the west should raise some questions , www.theguardian.com, accessed August 11, 2014.

- ↑ Kaspar Rosenbaum: South Ossetia: The West in the Propaganda Battle ( Memento from August 18, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ "That mustn't be" Gabriele Krone-Schmalz on the media coverage of Russia ( Memento from April 18, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ http://www.kremlin.ru/acts/19805 Homepage of the Kremlin, December 9, 2013, accessed on August 19, 2014

- ↑ Putin dissolves RIA Novosti and founds a new media conglomerate , derStandard, December 9, 2013

- ↑ Cold, unscrupulous - successful ?: With power and blackmail, President Putin has brought Ukraine back into Moscow's sphere of influence. Not his only political success this year. What is the man doing in the Kremlin? , Spiegel 51/2013 of December 16, 2013

- ↑ Ulrich Clauß: Anatomy of the Russian information war in networks . In: Die Welt (online edition), May 31, 2014

- ^ Julian Hans: Putin's trolls . In: Süddeutsche Zeitung (online edition), June 13, 2014; Christian Weisflog: Propaganda on the Net Putin's Internet pirates . In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung (online edition), June 18, 2014.

- ↑ Anne Will loves Russian , Euromaidanpr, April 30, 2014

- ↑ Analysis: The Ukraine crisis on German talk shows , Federal Agency for Civic Education, Russia and Ukraine Factor Figure 8