Kleverlandisch

Kleverländisch ( Dutch Kleverlands ) is a north Lower Franconian dialect group in North Rhine-Westphalia and in neighboring areas of the Netherlands. This dialect is closely related to Südgelderschen (Zuid-Gelders) and Ostbergic , which is adjacent to the southeast .

As an alternative name in Germany today, North Lower Franconian is also common.

Umbrella languages

Due to its eventful history, Kleverländisch was under the strong influence of the Dutch language until the end of the 19th century and was rethought by it. As a result, the dialect was written using Dutch grammar and spelling . That is why Kleverländisch was known for a long time under the name Deutschniederländisch (nld. Duits Nederlands ).

The German scholar Willy Sanders wrote about the close degree of kinship between the Lower Rhine , which also includes the Kleverland, and Dutch:

“The close relationship between the Lower Rhine and today's Dutch have their natural reason for the common Lower Franconian language character. In conjunction with the earlier interweaving of a political-territorial nature (e.g. the Duchy of Geldern with its four 'quarters' Roermond, Nijmegen, Arnhem, Zutphen), this led to the fact that on the left Lower Rhine a language type closely related to Dutch, popular even up to our century 'Dutch' was spoken. "

The Germanist Theodor Frings even thought further in this regard. He called for the general integration of the Lower Rhine into Dutch:

"One should beat the Lower Rhine north of the line of phonetic shifting, ie in Geldern, Mörs, Kleve, to Dutch ."

middle Ages

In the Middle Ages , the Lower Rhine was one of those areas in which the Middle Dutch language was used. In the 15th century, with the expansion of Cologne, the advance of Central German , more precisely Old Cologne , and from the 16th century of High German into the Lower Franconian language area began.

16th Century

In 1544 Cologne had introduced common German for its domain, and with it the modern written German language expanded to the north and west. Cologne extended its linguistic sphere of influence far into what would later become the Netherlands. In the 16th century, the Uerdinger line created a new balance between the Cologne Ripuarian and the Lower Franconian dialects and, as a result, today's Limburg dialects , which stood between Lower and Middle Franconian and were purely transitional dialects.

But the introduction of the written German language ended at the borders of the Habsburg Netherlands , at which the House of Habsburg was able to acquire the northern provinces between 1524 and 1543. In this “ Burgundian ” heritage, French was the major cultural language. In the seven northern provinces, however, a Lower Franconian / Dutch written language had gained significantly in influence, based on the dialects of the provinces of Holland and Brabant and which radiated far into the Lower Rhine region in the 16th century (Brabant expansion) . The Lower Rhine and partly also the Westphalian dialects of the Westmünsterland and beyond were strongly influenced by the Brabant-Dutch written language.

17th century

In the 17th and 18th centuries, the political borders on the Lower Rhine were redrawn. In 1614, Kur-Brandenburg was able to acquire its first properties on the Lower Rhine, where it inherited, among other things, the Duchy of Kleve .

In the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713, the Habsburg upper quarter of Roermond of the old Duchy of Geldern (under Habsburg since 1543) was divided among its neighbors:

- Prussia received most of the upper quarters. It received the offices of Kessel (with the larger communities of Kessel, Venray , Horst , Sevenum, Well, Afferden and Middelaar), Straelen , Geldern (with the larger communities of Geldern and Rayen ), Wachtendonk and Krickenbeck with the exclave of Viersen . These areas formed the Prussian Upper Quarters .

- The Netherlands received most of the Monfort office with the exclaves Venlo , Beesel and Nieuwstad . This area formed the static upper quarter .

- The House of Habsburg could only keep a small part of the Monfort office for its sphere of influence. It kept the communities of Roermond , Swalmen , Elmpt , Niederkrüchten and Wegberg . In addition, the municipalities of Meijel , Nederweert , Weert , Wessem , Kessenich , Obbicht , Herten and Maasniel were acquired. These areas formed what was now the Austrian Upper Quarters . (see also Austrian Geldern )

- The Duchy of Jülich was able to acquire and incorporate the enclave of Erkelenz , which had previously belonged to the Monfort office. This area was also known as Jülisches Oberquartier .

With the incorporation of the Lower Rhine areas into Prussia, German was formally introduced there as a written language. But German was only able to assert itself differently in these areas. At the end of the 18th century, the Lower Rhine area and the Rheinberg office, which belongs to Cologne , were in competition with two high-level and cultural languages, while in the county of Moers, including the then tiny cities of Krefeld and Duisburg, only German was used.

The right-lip area of the former Duchy of Kleve was already bilingual. In addition to German, Dutch was also used; German was only used in the then official city of Wesel and the surrounding area. The Klever area between Lippe and Maas was also bilingual, with Dutch clearly being preferred here. Only the city of Kleve and the Palatinate settlements were dominated by written German.

In the area of the former Duchy of Geldern, Dutch dominated over German. In the upper district of Gelderland, the Meuse already played the role of a language border: while the area to the left of the river with the towns of Venray and Horst used only Dutch almost exclusively, German was also used to a limited extent on the right of the Meuse and in the enclave of Viersen. This area was therefore only predominantly Dutch-speaking. The Gelderian Niederquartiere (which today essentially make up the Dutch province of Gelderland ) only used Dutch.

The Rheinberg office, which belongs to Cologne, was also bilingual at that time, although preference was given to German. In contrast to the rest of the Duchy of Jülich, the former Gelderian enclave of Erkelenz mainly used Dutch.

19th century

Between 1803 and 1810 the Lower Rhine area was incorporated into the French Empire. The area on the left bank of the Rhine was incorporated into the Roer department in 1806 and that on the right bank, with the exception of the city of Wesel, was incorporated into the Lippe department . Wesel and its surrounding area was added to the Roer department. In the same year the area on the right bank of the Rhine was connected to the newly appointed and enlarged Grand Duchy of Berg . However, in 1810 this area was annexed and incorporated by the French Empire .

As a result, German was replaced by French as the official language. For their part, the people of Lower Rhine favored Dutch, which was now able to prevail again as the umbrella language. The German was even pushed back from those areas of the Lower Rhine where it was predominantly used before.

In 1815, as a result of the Congress of Vienna , the borders on the Lower Rhine and the Maas were redrawn. The Lower Rhine area, which was again annexed to Prussia, now formed the province of Jülich-Kleve-Berg , and German was prescribed there as the sole standard language. In 1824 this province was merged with the "Lower Rhine Province" to the south to form the new Rhine Province . In 1827, at the urging of Prussia, Dutch was banned as a church language by the Bishop of Münster . A year later, due to an ordinance issued by the regional president, teaching in the schools of Preußisch- Obergeldern was only allowed in High German. With the attempt of the Prussian state to make the Lower Rhine monolingual in favor of the German, and which could be sure of the support of the Roman Catholic and the Protestant Church in this project, the population reacted with an increased adherence to the New Dutch, which little was later to be replaced by modern standard Dutch. Catholics and Reformed now forced the exclusive use of Dutch: while the Reformed (before the introduction of standard Dutch) forced a Dutch-Brabant variant, the Catholics used a Flemish-Brabant variant, thereby contradicting the official language policy of the Roman Catholic Church in Germany.

During the revolutionary years of 1848/49 the state tried to purposefully push Dutch back out of this area. Dutch was only allowed as the cultural and church language of the Reformed .

Between the years 1817 and 1866 an Evangelical Regional Church ( Unierte Kirche ) was established in Prussia , which combined Lutheran and Reformed teaching . As a result, the Reformed church service in the Lower Rhine was also to be held in German alone, and Dutch slowly lost its former status in this region.

After the founding of the German Empire (1871) on the Lower Rhine, only the use of German was permitted by all authorities and offices. Previously, Dutch was used as a school language in some municipalities until the middle of the 19th century or was taught as a second language alongside German. Until about 1860 it was still possible in the Lower Rhine region to submit requests and the like to authorities and offices in Dutch. At the turn of the century, the Lower Rhine was considered monolingual German.

20th century

At the turn of the century, German had established itself as the dominant umbrella language on the Lower Rhine and replaced Dutch. Only the group of the Old Reformed still used Dutch as the church language until it was abolished by the National Socialists in 1936 .

Iso-closed limitation

It is extremely difficult to distinguish Kleverland from other related idioms . For example, the linguistic differences between Kleverland and the neighboring Südgelder (i )schen (ndl. Zuid-Gelders ) in a Brabant -Gelder transition area in the Netherlands are small, so that today both language variants are sometimes combined in order to separate them from the Gelderian dialects ( Gelders-Overijssels) of the Gelderland.

But it is also difficult to distinguish it from Brabant, as this had a major influence on the Lower Rhine, especially since the 16th century. Thus, on various occasions, Kleverland, southern Gelderian and Brabantian were combined under the umbrella term Brabantian .

Today isoglosses are mainly used to distinguish Kleverland from related idioms :

The Uerdinger line ( ik / ich -Isoglosse) south of Venlo separates Kleverland from Limburg . Recent research shows that the actual border between Limburg and Kleverland is actually higher, between Venray and Horst. Sometimes, however, especially in the Netherlands, the Diest-Nijmegen or houden / hold line (after the ou / al -Isoglosse) is used. According to the Dutch Germanists, this isogloss separates Kleverland from neighboring Brabant and the other Dutch dialects. The majority of Germanists in German use the ij / ie -isogloss (so-called mijn / mien -line), which is also known as the ijs / ies -isogloss. The unified plural line weakening to the north (so-called "Westphalian line") finally separates Kleverland from Lower Saxony.

distribution

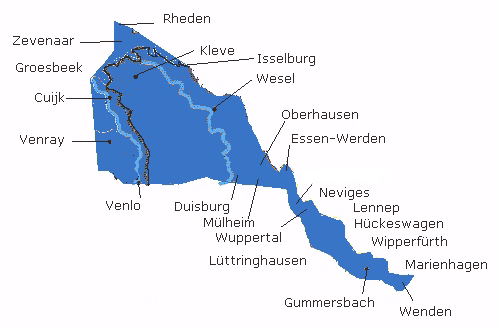

The Kleverländisch includes:

- The Klevisch-Weselic spoken in the lower Lower Rhine and the dialects of the western (Rhenish) Ruhr area ( Duisburg , northern and western districts of Oberhausen ),

- The dialects of Ostberg can be added - purely formalistically (Uerdinger line as border line in the west on the one hand and Westphalian line in the east on the other hand). In the meantime, however, these are also regarded as a separate dialect group of Lower Franconian, as they are characterized by differently strong influences from Ripuarian on the one hand in the area around Mülheim an der Ruhr, Essen-Kettwig and Essen-Werden , and on the other in the area around Velbert- Langenberg , Westphalian influences are characteristic. The Wenker sentences quoted below under “Language Examples” are in any case not exemplary for the Ostberg dialect group.

- The dialects spoken in the Noord-Limburg (NL) region.

- The dialect of Venlo (NL, me -Quartier).

- The dialect of Cuijk (NL).

Language examples

- "Ek heb still efkes afgewaachd, whether dat, wach'e min seggen wold."

- "I just waited a moment to see what you wanted to tell me."

- (Ndl.) "Ik heb nog even afgewacht (op dat) wat je (ge) me zeggen wou."

- "En den Wenter stüwe di drööge Bläär dörr de locht eröm" ( Georg Wenker sentence 1)

- "In winter the dry leaves fly around in the air."

- (Ndl.) "In the winter waaien (stuiven) de drug bladeren rond in de lucht."

- "Et sall soon üttschaije te shnejje, then you would be who bater." (Wenker sentence 2)

- "It will stop snowing immediately, then the weather will be better again."

- (Ndl.) "Het zal zo ophouden (uitscheiden) met sneeuwen, then wordt het weer weer beter."

- "Hej es vörr four of säss wääke troubled." (Wenker sentence 5)

- "He died four or six weeks ago."

- (Ndl.) "Hij is four of zes weken geleden storven."

- "Het for what te had, the kuuke makes sense to de onderkant heel schwaort." (Wenker sentence 6)

- "The fire was too hot, the cakes are burned all black below."

- (Ndl.) "Het vuur was te heet, de koeken zijn aan de onderkant helemaal (geheel) zwart aangebrand (aangeschroeid)."

- "Hej dütt die eikes ömmer special salt än pääper ääte." (Wenker sentence 7)

- "He always eats the eggs without salt and pepper."

- (Ndl.) "Hij eet de eitjes altijd zonder zout en peper."

The Duisburg Johanniter Johann Wassenberch kept regular records of local and global events in the 15th and 16th centuries, which provide information about the language of the Lower Rhine at that time:

- 's doenredachs dair nae woerden the twe court end op raeder fed up. Eyn gemeyn sproeke: 'Dair nae werck, dair nae loen'. The other vyf ontleipen end quamen dat but nyet goit en was.

- (oe = u, ai = aa, ae = aa)

- “On the Thursday after, the two were judged and put on wheels. A well-known saying: 'As the work, so the reward'. The other five fled and escaped, which wasn't good. "

- Nld. “The next donderdag will be twee veroordeeld en op raderen. Acknowledging: 'Zoals het werk, zo is het loon'. De other vijf ontliepen [het] en ontkwamen, wat toch niet goed was. "

Dialect and written language

In the 12th century, in the Rhine-Maas triangle - the area in which the Kleverland and Limburg dialects are spoken today - the so-called Rhine - Maasland written language emerged. Although this had many elements of regional dialects, it is not to be equated with these. The Niederrheinisches Platt was the spoken language of the - often not literate - common people; The Rhenish Maasland written language, on the other hand, was the written language of the upper classes and law firms. The Rhenish Maasland written language had largely replaced Latin as the written language until it lost its importance in the 16th century; on the one hand in favor of the "High German" spreading northwards via Cologne, on the other hand in favor of a separate written language emerging in today's Netherlands. However, this "standard German written language" could not spread equally quickly everywhere on the Lower Rhine. For a long period of time, German and Dutch coexisted in some cities (including Geldern, Kleve, Wesel, Krefeld), and decrees were issued in both written languages.

From the 18th century, the linguistic separation between the (German) Lower Rhine and the (Dutch) Maas area was complete. The respective high-level and written languages went their separate ways. Kleverland and Limburg as spoken dialects outlasted the new borders and persisted into modern times.

See also

- Kleve # Klever Platt

- Lower Franconian

- Duisburg Platt

- Krieewelsch

- Limburgish

- Mölmsch

- Rheinberger Platt

- German dialects

literature

- Georg Cornelissen , Peter Honnen , Fritz Langensiepen (eds.): Das Rheinische Platt. An inventory. Handbook of Rhenish Dialects, Part 1: Texts. Rheinland-Verlag, Cologne 1989, ISBN 3-7927-0689-X .

Notes and individual references

- ↑ Willy Sanders: Gerts van der Schüren 'Teuthonista' and the historical word geography. In: Jan Goossens (Ed.): Low German contributions. Festschrift for Felix Wortmann on his 70th birthday. Series Low German Studies, Volume 23 (1976), p. 48.

- ^ Theodor Frings, Gotthard Lechner: Dutch and Low German. Berlin 1966, p. 21 ff.

- ↑ Bestaande dialect limits Limburg knock niet . In: Radboud Universiteit . ( ru.nl [accessed on April 29, 2018]).

- ↑ a b Today politically slammed as Noord-Limburgs to Limburgish .

- ↑ Georg Cornelissen: Small Lower Rhine Language History (1300-1900). Verlag BOSS-Druck, Kleve, ISBN 90-807292-2-1 , pp. 62-94.

- ↑ a b Irmgard Hantsche: Atlas for the history of the Lower Rhine. Series of publications by the Niederrhein Academy, Volume 4, ISBN 3-89355-200-6 , p. 66.

- ^ Dieter Heimböckel: Language and literature on the Lower Rhine. Series of publications by the Niederrhein Academy, Volume 3, ISBN 3-89355-185-9 , pp. 15–55.

Web links

- Cleefs dialect of the lower Lower Rhine ( Memento from May 19, 2001 in the Internet Archive )

- Plattsatt - dialect in Kleve and elsewhere