Srinivasa Ramanujan

Srinivasa Ramanujan, FRS ( Tamil : ஸ்ரீனிவாஸ ராமானுஜன் , sriːniˈʋaːsə raːˈmaːnudʒən ; also Srinivasa Ramanujan Iyengar; born December 22, 1887 in Erode ; † April 26, 1920 in Chetpet , Madras ) was an Indian mathematician . He acquired his mathematical knowledge autodidactically from specialist literature and possessed an extraordinary talent for solving analytical and number theoretic problems intuitively, usually without being able to first provide a solution or proof.

His mathematical skills were promoted at school, but a degree failed because of his specialization. Living at subsistence level, he did mathematics privately and wrote down his findings in so-called notebooks . Attempts at scientific recognition were initially unsuccessful, until in 1913 the British mathematician Godfrey Harold Hardy recognized his talent and brought him to England, where he made numerous important discoveries. In 1919 Ramanujan returned to India as a well-known scientist and died in 1920 at the age of 32. He had to struggle with health problems all his life.

The patronymic Srinivasa "(the first syllable is pronounced Schri )" was mostly abbreviated as S. by Ramanujan. Ramanujan was his nickname. The last name Iyengar, which also indicates the caste affiliation, is optional. Ramanujan means "the little brother (anuja) of Rama ", this name was also chosen with a view to Ramanuja .

Life

Youth and education

Srinivasa Ramanujan was born on December 22, 1887 into a family of Orthodox Tamil Brahmins belonging to the Iyengar caste . After he was born in Erode , where his maternal grandparents lived and where his mother traditionally went to give birth, he grew up in his parents' home (the mother returned there a year after the birth) in Kumbakonam, initially in a small house on Sarangapani Street . His father K. Srinivasa Iyengar worked as an office clerk in a sari shop, his mother Komalatammal Srinivasa was a trained housewife and worked as a singer of liturgical chants ( bhajan ) in a nearby temple . Half of the income went to the temple, the other half to the singers. His mother received 5 to 10 rupees a month compared to his father's earnings of 20 rupees a month. The family lived in poor conditions and had to move frequently. Three of his four brothers, who were born later, died in infancy. Even as a toddler in Erode he was noticed for his sensitivity and obstinacy, so he rolled in the dirt on the floor when he did not get what he wanted to eat. He hardly spoke for the first three years of his life, but quickly caught up when he learned to pronounce a traditional method by drawing the Tamil letters in a layer of rice on the floor under the guidance of his grandfather.

In December 1889, Ramanujan fell ill with smallpox , which killed thousands in the region. Then he went with his mother to the city of Kanchipuram , where his grandparents from Erode had previously moved.

On October 1, 1892, at the age of four, he entered preschool and in March 1894 the Telugu Medium School. Then his grandfather lost his position as judge in Kanchipuram and Ramanujan moved back to Kumbakonam with his mother. There he attended the Kangayan Primary School. After the death of his paternal grandfather, he was sent to live with his maternal grandparents, who now lived in Madras (now Chennai). There Ramanujan avoided school and was given a guard to ensure school attendance. After six months he moved back to Kumbakonam.

Ramanujan developed a close relationship with his mother, who raised him as a brahmin and taught him the traditions, the caste system , the Puranas , religious songs and the celebration of puja . His father was rarely home.

At the Kangayan Primary School, shortly before his tenth birthday, Ramanujan was considered the best student in the district in the subjects English, Tamil , geography and arithmetic . He then went to Town High School and was soon noticed as a math prodigy : at the age of eleven, he was mathematically superior to two neighborhood college students. He worked through books on advanced trigonometry by Sidney Luxton Loney himself within two years. However, his interests and skills put him in danger of becoming an outsider:

“By the time he was fourteen in fourth grade, some of his classmates had already begun to disqualify Ramanujan as someone who was floating in the clouds, someone who was difficult to communicate with. 'We (teachers and students) rarely understood him,' recalled a classmate half a century later. It is easy to imagine some teachers feeling uncomfortable about his abilities. But most of the school apparently had a great respect for him, regardless of whether they understood him or not. "

In 1902 Ramanujan received certificates for special merits and awards and helped the school management to distribute the 1200 students among the 35-member teaching staff. He began to be interested in infinite rows . At the age of 16 he came across the book A Synopsis of Elementary Results in Pure and Applied Mathematics by George Shoobridge Carr with over 5000 mathematical theorems . When he finished school in 1904, he received the K. Ranganatha Rao prize for his mathematical achievements, which enabled him to receive a scholarship at the Government College in Kumbakonam, the so-called "Cambridge South India". At the age of 17 Ramanujan calculated the Euler-Mascheroni constant in his head to 15 places behind the decimal point.

He began to study at the Government Arts College in Kumbakonam, but he neglected the compulsory subjects English and Sanskrit and therefore lost his scholarship again in January 1905, so that he had to drop out. In August 1905 he moved to Visakhapatnam and enrolled at Pachaiyappa's College in Madras, but had to give up this study because of an illness and failed exams.

Life in india

Without training or employment, Ramanujan lived on the subsistence level and often went hungry. At his mother's request, on July 14, 1909, he married the ten-year-old S. Janaki Ammal (1899–1994), who continued to live with her parents. A few months later he fell ill with hydrocele testis , an accumulation of fluid in the testicular cover ; in January 1910 he was operated on.

After recovering Ramanujan took a job as a clerk in Madras, and he also gave students of Presidency College tuition in mathematics. He applied to District Chief V. Ramaswami Iyer, who had recently started the Indian Mathematical Society (IMS), with his notebooks of formulas for a position in the finance department. Iyer later said:

“I was impressed with the extraordinary math results that were in them [in the notebooks]. [...] It never occurred to me to suppress his talent by taking up a position on the bottom rung of the finance department. "

Iyer sent Ramanujan with recommendation papers to be friends with mathematicians in Madras. They recommended him to the District Head of Nelluru and Secretary of the IMS, R. Ramachandra Rao. Ramanujan calculated elliptic integrals , hypergeometric functions and his own theory of divergent series, and Ramachandra Rao recognized his brilliance. In Madras, Ramanujan continued his work with the financial help of Ramachandra Rao and published in the IMS magazine.

One of the first problems he dealt with in the booklet was calculating the expression

He waited a long time for a solution from the readership, but none came, so he presented the solution himself. He used the identity :

With the formulation of the task and the solution 3.

Another contribution to the journal of the IMS was the seventeen-page treatise Some Properties of Bernoulli's Numbers , in which he described properties of the Bernoulli numbers . Among other things, he presented a method of calculating on the basis of other Bernoulli numbers using recursion relations.

At first, however, Ramanujan's texts contained a number of errors. The editor of the journal, M. T. Narayana Iyengar, mathematics professor at Central College in Bangalore , wrote:

"Mr. Ramanujan's methods were so brief and novel, and his presentation so lacking in clarity and precision, that normal [mathematical readers], not used to such intellectual gymnastics, could hardly follow him. "

In January 1912 he took up a position in the general accounting office of Madras, where he received a monthly wage of 20 Indian rupees . Now his 13-year-old wife moved in with him. On March 1, 1912, he moved to the accounting office of the Port Authority in Madras, his monthly salary rose to 30 rupees. The work was easy for him and gave him time for research. His superior, Sir Francis Spring, and his colleague S. Narayana Iyer, also a member of the IMS, encouraged him to do so.

Contact with European mathematicians

Sir Francis Spring, S. Narayana Iyer, R. Ramachandra Rao and Edward William Middlemast endeavored to interest European mathematicians in Ramanujan's work. However, although Micaiah John Muller Hill (1856–1929) of University College London admitted that Ramanujan had "a sense of mathematics and some talent," he found his lack of academic education too great to be accepted by better mathematicians, and left it with advice for the future. In 1912 Ramanujan wrote to Henry Frederick Baker and Ernest William Hobson , two leading mathematicians at Cambridge University . He got his documents back without comment.

Finally, he wrote to the internationally known mathematician Godfrey Harold Hardy , who also taught at Trinity College in Cambridge . His nine-page letter dated January 16, 1913, filled with formulas, began with the words:

“Dear Sir,

I would like to introduce myself as an accounting clerk in the Madras Port Authority with an annual income of £ 20. I am now 26 years old. I don't have a university degree, but I did the usual classes. [...] I have not followed the conventional, regulated path that one follows in a lecture at the university, but rather I am going my own, new path. [...] I ask you to look through the enclosed papers. Since I am poor, I would like to publish my sentences if you are convinced that they have value. "

Hardy thought he was an impostor at first. Some of the formulas were known to him, but most of them "hardly seemed believable". One of them was at the end of the third page of the letter:

- For

Hardy believed he could prove this equation, which included the gamma function and a definite integral (an area in which he believed himself to be an expert). He succeeded in doing this later, even if the evidence about certain integrals in the letter was not easy. What fascinated Hardy above all, however, were the results listed in the letter over infinite series, such as

and

The first result comes from Gustav Bauer and had been known for some time from the theory of Legendre polynomials . But the second and two other results were completely new to Hardy and, in his opinion, presented a much more serious problem than it appeared at first glance. They were related to the theory of hypergeometric functions , which had first been investigated by Leonhard Euler and Carl Friedrich Gauß . Hardy found Ramanujan's results on infinite series "much more fascinating, and it quickly became clear that Ramanujan had much more general theorems and withheld a lot." The results necessary to prove it were later published in a monograph by Wilfrid Norman Bailey . Later it was found that Ramanujan already knew an identity before 1910 ( Dougall-Ramanujan identity ) from which many such results could be derived.

About the results on the last page of the letter concerning elliptic functions , Hardy said:

“I hadn't seen anything remotely similar before. One glance at it was enough to see that only a mathematician of the highest order could have written it down. They had to be true, because if they weren't, no one would have had the imagination to invent them. Finally [...] the author had to be absolutely honest, because great mathematicians are more common than thieves and charlatans with such incredible ability. "

Hardy showed Ramanujan's letter to his friend and colleague, John Edensor Littlewood . Littlewood also amazed the Indian's achievements. After discussing the two Englishmen, Hardy noted that the letter and formulas "are probably the most remarkable I have ever received," and that Ramanujan is "a mathematician of the highest quality, a man of both extraordinary originality and strength " be. Another colleague of Hardy's, Eric Harold Neville , who teaches in Madras , found with regard to the theorems and formulas:

"Not one could have been found in the world's most advanced research."

Hardy's reply by letter reached Ramanujan on February 8, 1913 in Madras. In it the Briton expressed his interest in the work of the Indian:

“I found your letter and your sentences extremely interesting ..... I particularly want your evidence for these claims here. You will understand that in this theory everything depends on the rigorous accuracy of the evidence. "

In the first days of February before Ramanujan received the letter, Hardy asked the Indian authorities to prepare Ramanujan's trip to Cambridge. Upon the arrival of the letter, Arthur Davies, the secretary of the Advisory Committee for Indian Students, contacted the Indian to plan the crossing, but the Indian declined the invitation to Britain because, as an Orthodox Brahmin , he was afraid he would to lose his caste membership if he went to a foreign country. His mother was also concerned. Instead, Ramanujan sent another letter with formulas to Hardy, to which he added the words:

"I have found in you a friend who regards my work with benevolence."

Gilbert Walker , a former Cambridge math professor, looked at Ramanujan's work and asked him to come to England too. The Indian mathematician B. Hanumantha Rao also wanted to persuade his compatriot to do so. He invited his work colleague S. Narayana Iyer to an interview with the Education Authority, Department of Mathematics, to find out "what we can do for S. Ramanujan". At that meeting it was agreed to grant Ramanujan a two-year research fellowship at the University of Madras . He should receive 75 rupees a month.

During his time at the university, Ramanujan continued to publish math problems and their solutions in the journal of the IMS. During this time he worked out ways to solve certain integrals more easily, revised the integral theory of Giuliano Frullani from 1821 and developed generalizations for estimating previously seemingly unsolvable integrals.

Finally, Ramanujan's parents agreed to the trip. On March 18, 1914 (other sources cite March 17), Neville and Ramanujan boarded the SS Nevasa in Madras and entered London on April 18. Ramanujan found temporary accommodation with Neville on Chesterton Road in Cambridge. Neville accompanied him on his first steps in England in a friendly way. In June, Ramanujan moved into rooms at Whewell's Court at Trinity College, about a five-minute walk from Hardy's rooms at New Court at Trinity College. In October 1915 he moved to Bishop's Hostel, which was even closer to Hardy. He mostly stayed in Cambridge, even during the semester break, but occasionally visited London, such as the British Museum and the zoo, and once he was in a performance by Charley's aunt . Because of his vegetarian eating habits, he did not take part in the common college meals and other college members rarely saw him when he "waddled" in slippers across the Great Court, as he was not wearing shoes that are common in the West.

Scientific success in England

Immediately after his arrival, the Indian started work. First he showed Hardy his notebooks. Although he had sent the Englishman about 120 formulas together in both letters, the books contained considerably more approaches, theorems and solutions. Hardy realized that some calculations were wrong and some had already been discovered, but the majority were new breakthroughs. Littlewood and Hardy were deeply impressed, and the former said:

"I think he's at least a Jacobi ."

Hardy also drew parallels between Ramanujan and Jacobi:

"[I] can only compare him to Euler or Jacobi."

There were serious differences in character and culture between Ramanujan and Hardy. The Briton was an atheist and saw himself as a supporter of evidence for theories and a certain rigor and rigor of his science. The Indian, on the other hand, was a deeply religious person who also relied primarily on his intuition during his work and almost never proved his sentences. During the years together, Hardy also tried to fill the knowledge and educational gaps that Ramanujan had in other disciplines, without affecting his mathematical inspiration. The collaboration was intense, and it was not uncommon for Ramanujan to work thirty hours straight and then sleep for twenty hours.

On March 16, 1916, Ramanujan was awarded the Bachelor of Arts by Research due to the recognition of his research work (this corresponds to about a doctorate; doctorates were only available in Cambridge from 1917 and were not necessarily required afterwards, more important was a fellowship at a college), honoring his work on highly composed numbers , which was published as a treatise in the journal of the London Mathematical Society . Hardy said these calculations were among the most unusual in mathematics to date, and that Ramanujan handled them with extraordinary ingenuity. On December 6, 1917, Ramanujan was elected to the London Mathematical Society.

On February 18, 1918 he was made a Fellow of the Cambridge Philosophical Society . Three days later, his name appeared on the candidate list for the title of Fellow of the Royal Society ( FRS ). He had been proposed by numerous well-known mathematicians "for his investigation of elliptical functions and number theory". He was supported by Hardy, Littlewood, Percy Alexander MacMahon , Joseph Larmor , Thomas John I'Anson Bromwich , Seth Barnes Nicholson , Alfred Young , Edmund Taylor Whittaker , Andrew Russell Forsyth and Alfred North Whitehead, among others . But Hobson and Baker, the two professors who had returned Ramanujan's request five years earlier without comment, also supported the candidacy. The award took place on May 2nd. Ramanujan was only the second Indian to receive this honor and one of the youngest fellows. In the same year, on October 10th, he also received the title of Fellow of Trinity College Cambridge .

Years after Ramanujan's death, the Hungarian mathematician Paul Erdős asked Hardy about his greatest contribution to mathematics. Without hesitation, Hardy called Ramanujan's discovery, describing it as "the only romantic incident in my life."

Illness, return to India and death

Ramanujan had health problems throughout his life. In this respect, his stay in England was not good for him, especially since as a Brahmin he lived strictly vegetarian , which made his diet even more difficult during the First World War . After contracting bacterial dysentery twice , both tuberculosis and vitamin deficiency were diagnosed. Ramanujan's fatalistic attitude, which Hardy attributed to his Indian origins, also contributed to the fact that he paid too little attention to his own health.

The year 1917 was marked by disappointments for Ramanujan. Initially, he was not elected as a Fellow of Trinity College, as he had hoped (the college was then divided over the affair over the war opponent Bertrand Russell ). Then he fell so seriously ill that at times he feared for his life. The stay in the tuberculosis sanatorium in Matlock worsened his mood into a deep depression: the place was remote, the management dictatorial, the patients were isolated from the outside world, it was cold (which was thought to be therapeutically useful at the time), and he did not get the usual food. His work suffered from the illness, which in turn exacerbated his depression. In addition, he rarely received letters from his wife; as it turned out later, they were intercepted by his mother. In February 1918, Ramanujan attempted suicide by throwing himself on the rails in front of an incoming subway train, but an attentive guard managed to bring the train to a stop in time. Ramanujan suffered injuries that left deep scars on his shin. He was arrested and was only released thanks to Hardy's intervention. In late 1917, however, Hardy saw signs of improvement and wrote in a letter to Francis Dewsbury in Madras in January 1918 that Ramanujan had gained nearly 15 pounds and that his body temperature was stable.

Ramanujan decided to return to India after the war was over. As a Fellow of the Royal Society he was offered a professorship (Fellowship of the University) in Madras, which at 250 pounds offered him about the same salary as a Fellow of the Royal Society. Ramanujan wanted to get well first and even donated money from his income to the Royal Society, to the displeasure of his family, who had to rely on his support.

Ramanujan set out from England on February 27, 1919, reached India on March 13, and was received by his mother in Madras. Family conflicts broke out again when Ramanujan insisted that his wife Janaki, now 18 years old, come to him. His nature had changed, instead of being warm and friendly as before his departure, he now appeared to his friends depressed, cold and sullen, he was no longer well-fed as before his departure, but looked sickly and emaciated. He was considered to be sent to a sanatorium, but Ramanujan had become suspicious of doctors and often refused to advise them. At Hardy's urging, the Madras tuberculosis specialist and Professor PS Chandrasekhar were sent to Ramanujan, who clearly diagnosed tuberculosis.

In the summer the family moved from hot Madras to the cooler interior of the country, first to Kodumudi , where the mother's family had good connections, and from the beginning of September to the less remote Kumbakonam. At the beginning of 1920 Ramanujan was back in Chetpet , a suburb of Madras, where he once again experienced a productive phase. On January 12, 1920, he wrote to Hardy about the discovery of the mock theta functions. Until four days before his death, despite the fever and pain, he worked on his mathematical notebooks, the sheets of which his wife collected in a box.

Ramanujan died on April 26, 1920 in Chetpet in the Gometra house outside Huntington Road. His widow lived in Triplicane , a district of Madras, until her death in 1994 , where she later mainly earned her living as a self-employed tailor (and received a small pension from the University of Madras) and raised an adopted son of a deceased friend (W. Narayanan).

The doctor DAB Young examined Ramanujan's medical records and medical records in 1994 and suggested that he had died not of tuberculosis but of amoebic dysentery, which was rampant in Madras at the time. He was also of the opinion that Ramanujan's bacterial dysentery had not completely subsided and that the pathogens had remained in the body. In this way, amoebic dysentery could develop all the faster later.

The work

Ramanujan was mainly concerned with number theory during the five years in England . He became famous for many sum formulas that contain constants such as the circle number, prime numbers and partition functions , and he was a master at dealing with continued fractions . Among other things, he created a very good approximation formula for calculating the circumference of the ellipse .

Circle number calculation

One of his best-known findings is an equation for calculating the number of circles , which was published in 1914 and based on studies of elliptical functions and module functions :

The method converges rapidly and delivers to 9 increments over a proximity break with 80-digit counter is already a result, the 70 fractions with coincident:

In 1985, Bill Gosper used this approach to determine to 17 million decimal places.

Partition function

The asymptotic formula published by Hardy and Ramanujan in 1918 for the partition function gives the number of times a natural number decays :

- .

For example , it results in a value that is only 1.4% too high, which is around . Hardy and Ramanujan found an exact formula for the partition function whose first term is the above asymptotic value. This also impressed the English combinatorics specialist Percy Alexander MacMahon , who had calculated tables for the partition function using a formula from Euler - the value , laboriously tabulated by MacMahon, resulted directly from Ramanujan's formula. The work on the partition function was also the origin of the circle method, which was later made a central method of analytic number theory by Hardy and Littlewood.

Further findings

In total, Ramanujan found around 3,900 mathematical results in Cambridge, the majority of which were identity equations , most of which could be proven retrospectively.

In the years of working together with Hardy, numerous works were created on highly composed numbers , mock theta functions (pseudo theta functions) - which were puzzling for a long time, but whose theory received a great boom around 2010 ( Sander Zwegers , Kathrin Bringmann , Ken Ono ) - and the conjecture named after him about the Ramanujan tau function , which was proven by Pierre Deligne in 1974 . Together they proved Hardy and Ramanujan's theorem . This theorem provides the most accurate estimate to date for the number of different prime factors of an integer.

To give examples of the kind of Ramanujan's results, here are a few more equations that Ramanujan found:

Concepts named after Ramanujan

- Landau-Ramanujan constant (also named after Edmund Landau )

- Ramanujan Soldner constant (further developed theory of the German mathematician Johann Georg von Soldner )

- Ramanujan theta function

- Rogers-Ramanujan identities (developed in collaboration with British mathematician Leonard James Rogers )

- Ramanujan prime number

- Ramanujan sum

- Ramanujan conjecture (about the Ramanujan tau function)

- the open problem of Brocard and Ramanujan

- Ramanujan graph

- Ramanujan-Nagell equation

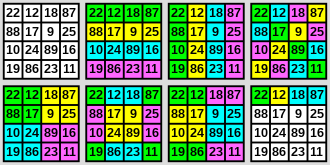

Magic square

An entire chapter of the first notebook is devoted to magic squares . He made the square on the left, the first line of which shows his date of birth.

Ramanujan's methods and educational gaps

Not all of Ramanujan's results were exact. In one of his first letters, for example, he gave a formula for the number of prime numbers below a fixed number in the form of an infinite series, which indeed gives an exact match for values up to around 1000 (and also provides a relatively good approximation for much higher values ), but overall, Littlewood found, is not exact. The formula was similar to that of Bernhard Riemann, with Ramanujan's formula not taking into account the complex zeros of the Riemann zeta functions . Although Ramanujan in analytical number theory (and especially the prime number distribution) had to fail (Littlewood) due to his lack of knowledge and the important necessity of strict proofs, especially here - where often seemingly plausible hypotheses later turned out to be false - Littlewood considered his contributions to be one of his most extraordinary achievements.

Hardy was often asked if Ramanujan had a special secret or "abnormal" methods that set him apart from other mathematicians. Hardy replied that although he could not answer that with absolute certainty, he did not believe it.

One shortcoming of Ramanujan was that he knew nothing of the theory of the functions of complex variables (he even got his knowledge of elliptical functions from the idiosyncratic presentation of the textbook by Alfred George Greenhill ), as Hardy stated in his book on Ramanujan. Later he learned some function theory, but to Hardy's astonishment he did not use Cauchy's integral theorem or the residual calculus , although as a formalist they should have suited him. Hardy characterized Ramanujan as a master in dealing with algebraic formulas and infinite series in a way that Hardy himself had not seen in any mathematician he knew and which made him comparable only to Euler or Jacobi. He also worked more than other mathematicians after Hardy by induction of numerical examples, for example on the congruences of the partition function he discovered. According to Hardy, he combined an extraordinary memory, patience and perseverance and extraordinary numeracy skills with an ability to generalize and to rapidly change the hypotheses he had made, as well as a sense of form which amazed and made him unique in his field . He saw it less as a tragedy that Ramanujan died early (according to Hardy, mathematicians were already relatively old at the age of 30 anyway) than that he was not promoted in India in his early years and had thus received a distorted view of mathematics. According to Hardy, despite profound and indomitable originality , he would have become a great mathematician had he been a little tamed in his youth but then less a Ramanujan than a European professor, and the loss might have been greater than the gain.

Anecdotes

A story that expresses Ramanujan's mathematical achievements comes from Hardy himself, who told it after Ramanujan's death. Hardy had taken a taxi with the number 1729 to Ramanujan, had thought a little about the number, but found nothing special, and instead of greeting Ramanujan, disappointedly told him what an uninteresting, meaningless number it was. Ramanujan, who was ill in bed, contradicted at once: in 1729 was even interesting than the smallest natural number that'll be written in two different ways as a sum of two cubes: . Hardy asked back if he also knew the answer to the corresponding problem for fourth powers. After a moment's thought, Ramanujan said he couldn't think of an example, but the first such number must be very large.

The number 1729 is now also known as the Hardy Ramanujan number and is the second taxicab number . The smallest solution to the fourth power is .

JE Littlewood once said that any positive integer is Ramanujan's personal friend.

Another story has been told by Prasanta Chandra Mahalanobis , Ramanujan's friend from Cambridge. In Ramanujan's room, he came across a brain teaser from Strand Magazine from December 1914. There was a series of houses with consecutive house numbers 1, 2, 3…. We were looking for the number of the house where the sums of all house numbers to the right or left are the same if the number of houses is greater than 50 and less than 500. After a short thought, Mahalanobis found house number 204 out of a total of 288 houses as the only solution in the given interval:

When he then read the task to Ramanujan, he not only found this special solution just as quickly, but also formulated a general solution for streets of any length in the form of a chain fraction. For example, 6 would be a solution for fewer than 50 houses, for a total of 8 houses:

Other interests and views of Ramanujan

According to Hardy's account, Ramanujan was only marginally interested in literature and art, but was able to distinguish good from bad literature. His knowledge of English was so poor that he could not have passed an exam; He could not read mathematical treatises in German or French at all. He was very interested in philosophy, politically he was a radical pacifist . Although he paid close attention to the observance of his religious conventions, he was not only convinced of his religion, but of the opinion that all religions were more or less alike. He was interested in the unusual, unexpected and strange and owned a small collection of books by squarers and other cranks (Hardy). Ramanujan himself provided two geometrical constructions for the approximate squaring of the circle .

Notebooks

Ramanujan's personal notes, the "notebooks", were partially lost for several years. His widow gave the four notebooks and several other manuscripts to the University of Madras after his death . Three years later, the local registrar Francis Drewsbury sent them to Godfrey Harold Hardy at the University of Cambridge. The originals of the first and second notebooks were later returned to Madras University.

The four books and the manuscripts contained a total of 3,000 to 4,000 mathematical formulas drawn up by Ramanujan (759 results in the first notebook). However, no evidence was attached to any. Together with Bruce Berndt , a mathematician from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign , George E. Andrews proved a large part of the formulas (using documents from Bertram Martin Wilson and George Neville Watson and with the participation of other mathematicians).

A publication of the notebooks was originally planned with the Collected Papers in 1927, but did not materialize for financial reasons. In 1929 Wilson and Watson planned to publish the notebooks, but this came to a standstill with Wilson's death in 1935 (in 1957 the Tata Institute for Fundamental Research in Bombay published a photostatic copy in two volumes, with the first, second and third notebook). At the end of the 1930s Watson lost interest in the publication, but his notes and those of Wilson were later used by Berndt and Andrews in their edition, and Watson published on material from the notebooks. The notebooks were later edited by Andrews and Berndt.

The second notebook is an extension and processing of the first notebook and was created before Ramanujan's stay in England. Both have over 300 pages and are largely arranged thematically (in the second notebook, 21 chapters of 256 pages and around 100 pages of unorganized material). He wrote to Hardy about 120 results (with one page missing from the first letter). The third notebook consists of only 33 pages.

The fourth notebook was made after Ramanujan's return to India and contains, among other things, material on the mock theta functions, Rogers-Ramanujan continued fractions and q-series. It was lost for decades, which earned it the nickname Lost Notebook . After Watson's death in 1965, Robert Alexander Rankin examined his estate and sent the Ramanujan writings that were still there on December 26, 1968 to the Wren Library of Trinity College. There the Lost Notebook was found by Andrews in the spring of 1976, in a box with items formerly belonging to Watson. Berndt said:

"The discovery of this lost notebook caused about as much turmoil in the mathematical world as the discovery of Beethoven's tenth symphony would cause in the musical world."

On December 22, 1987 (Ramanujan's 100th birthday), Ramanujan's Lost Notebook was published in the Narosa Publishing House , which is linked to Springer Verlag . The then Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi handed the first two copies of the book to S. Janaki Ammal Ramanujan, the mathematician's widow, and to George E. Andrews. However, no evidence has been found for some formulas to date.

Honors

Awards during his lifetime

- 1904: K. Ranganatha Rao prize for mathematics

- December 6, 1917: Member of the London Mathematical Society

- February 18, 1918: Fellow of the Cambridge Philosophical Society

- May 2, 1918: Fellow of the Royal Society

- October 10, 1918: Fellow of Trinity College Cambridge

Posthumous honors

- In 1962, the Indian government issued a stamp with Ramanujan's likeness to commemorate his 75th birthday. Today the mathematician graces a number of Indian postage stamps.

- In the Indian state of Tamil Nadu , Ramanujan's home state, State IT Day is celebrated every year on December 22nd, his birthday . This is to remind of the roots of this scientist and his origins from Tamil Nadu. The house on Saarangapani Street in Kumbakonam, where Ramanujan and his family spent most of his childhood, now houses an extensive museum about the mathematician.

- The ICTP Ramanujan Prize and the SASTRA Ramanujan Prize have been awarded since 2005 in memory of Ramanujan .

- In 2019, a team of researchers led by Gal Raayoni from Technion published a technical article on software they had developed, which, according to its authors, should imitate the way Ramanujan works. The computer program, called the “Ramanujan machine”, is said to have found previously unknown nested formulas using the trial-and-error method, which give the value of important constants such as pi, Euler's number e or values of the Riemann zeta function. Frank Calegari criticized the research team's claims as intellectual imposture.

- The asteroid (4130) Ramanujan , discovered on February 17, 1988, was named after him in 1989.

References to Ramanujan in culture

- In the film Good Will Hunting , math professor Gerald Lambeau cites Ramanujan - somewhat overdramatized - as a comparison for the giftedness of the young Will Hunting.

- The US crime series Numbers transferred Ramanujan's name to an Indian mathematician who specialized in combinatorics .

- The drama First Class Man, based on the novel by David Freeman, is about Ramanujan and his working relationship with Hardy.

- On April 21, 1998, the opera Ramanujan by the German-Indian composer Sandeep Bhagwati about the life of the mathematician was premiered in Munich's Prinzregententheater .

- The biographical film Ramanujan was released in 2014 .

- 2016 feature film appeared Poetry of the infinite (English: The Man Who Knew Infinity ), directed by Matthew Brown with the English actor Dev Patel in the role of Srinivasa Ramanujan and Jeremy Irons as G. H. Hardy .

Fonts

- With GH Hardy : Une formule asymptotique pour le nombre des partitions de n . Comptes Rendus 164, 1917, pp. 35-38.

- GH Hardy, P. Veṅkatesvara Seshu Aiyar, Bertram Martin Wilson (Eds.): Collected papers. Cambridge University Press, 1927; Reprint Chelsea Publishing Co. 1962; AMS Chelsea Publishing (Volume 159) 2000, ISBN 0-8218-2076-1 (with modern commentaries by Bruce C. Berndt).

- George E. Andrews, Bruce C. Berndt (Eds.): Ramanujan's Lost Notebook. Springer-Verlag, New York London 2005, ISBN 978-0-387-25529-3 .

- Bruce C. Berndt (Ed.): Ramanujan's Notebooks. (Five parts), Springer-Verlag, New York.

- Part I, 1985, ISBN 0-387-96110-0 .

- Part II, 1999, ISBN 0-387-96794-X .

- Part III, 2004, ISBN 0-387-97503-9 .

- Part IV, 1993, ISBN 0-387-94109-6 .

- Part V, 2005, ISBN 0-387-94941-0 .

- George E. Andrews, Robert Alexander Rankin (Eds.): Ramanujan - Letters and Commentary. American Mathematical Society, 1995, ISBN 978-0-8218-0470-4 .

- Ramanujan: The lost notebook and other unpublished papers. Narosa Publ. House / Springer, New Delhi 1988.

literature

- Godfrey Harold Hardy: Obituary, S. Ramanujan. Nature, Vol. 105, 1920, pp. 494-495.

- Godfrey Harold Hardy: Ramanujan - Twelve Lectures on the Subjects Suggested by His Life and Work. Chelsea Publishing Co, 1940, 1978 ISBN 0-8284-0136-5 .

- Godfrey Harold Hardy: Srinivasan Ramanujan (1887-1920) , Proc. London Math. Soc., Volume 19, 1920, pp. XL-LVIII, reprinted in Hardy et al. a. Ramanujan. Collected Papers , Cambridge UP, 1927, pp. XXI – XXXVI (with minor changes also in Proc. Roy. Soc., 1921)

- Robert Kanigel : Who knew the infinite. Vieweg-Verlag, 2nd edition 1995, ISBN 3-528-16509-X , German translation by Albrecht Beutelspacher of The Man Who Knew Infinity: a Life of the Genius Ramanujan. Charles Scribner's Sons, New York 1991. ISBN 0-684-19259-4 .

- Eric Harold Neville : Srinivasa Ramanujan. Nature, Vol. 149, 1942, pp. 292-295

- SR Ranganathan : Ramanujan: the Man and the Mathematician , Bombay: Asia Publishing House 1967

- Suresh Ram: Srinivasa Ramanujan , New Delhi, National Book Trust, 1972, 1979.

- K. Srinivasa Rao: Srinivasa Ramanujan - A Mathematical Genius. East West Books, Madras 1998.

- George E. Andrews (Ed.): Ramanujan revisited. (Urbana-Champaign, Ill., 1987), Academic Press 1988

- George E. Andrews, Robert Alexander Rankin : Ramanujan: Essays and Surveys. American Mathematical Society, 2001, ISBN 978-0-8218-2624-9 .

- Bruce C. Berndt: An Overview of Ramanujan's Notebooks. In: Charlemagne and His Heritage: 1200 Years of Civilization and Science in Europe. (Eds. PL Butzer, W. Oberschelp, H. Th. Jongen), Turnhout, 1998. pp. 119-146.

- Bruce C. Berndt, S. Bhargava: Ramanujan for lowbrows. In: American Mathematical Monthly. Volume 100, 1993, p. 644 ( mathdl.maa.org ).

- Robert Alexander Rankin : Ramanujan's Manuscripts and Notebooks , Bulletin London Math. Soc., Volume 14, 1982, pp. 81-97, Part 2, Volume 21, 1989, pp. 351-365

- Lokenath Debnath: Srinivasa Ramanujan (1887-1920) and the theory of partitions of numbers and statistical mechanics. A centennial tribute , International Journal of Mathematics and Mathematical Sciences, Volume 10, 1987, Issue 4, pp. 625-640, European Digital Mathematics Library

- Don Zagier : Ramanujan to Hardy. From the first to the last letter. In: Communications DMV. Volume 18, 2010, pp. 21-28 ( people.mpim-bonn.mpg.de PDF).

Web links

- John J. O'Connor, Edmund F. Robertson : Srinivasa Aiyangar Ramanujan. In: MacTutor History of Mathematics archive .

- Website on Srinivasa Ramanujan - by Prof. K. Srinivasa Rao, Chennai, with numerous scans of the articles and notebooks, June 2002 (English)

- Alladi Krishnaswami (Ed.): Srinivasa Ramanujan: Going Strong at 125, Part I. Notices AMS, December 2012 and Part 2. Notices AMS, January 2013

- K. Srinivasa Rao: Srinivasa Ramanujan

- A genius with intuition: Ramanujan. (PDF) Short biography, Quarks & Co , April 5, 2005

- Holger Dambeck: Mathematicians bow to Ramanujan. In: Spiegel online . December 22, 2012 ( spiegel.de ).

- Martin Koch: Perhaps the greatest math genius died too early. Did Ramanujan know the infinite? In: Berliner Zeitung . April 29, 1995 ( berliner-zeitung.de ).

References and comments

- ^ Robert Kanigel, translated by Albrecht Beutelspacher: Who knew the infinite ; The life of the brilliant mathematician Srinivasa Ramanujan, Springer-Verlag, March 8, 2013, pp. 8–9 ( limited preview in the Google book search), accessed on April 26, 2020

- ↑ After Robert Kanigel: Who knew the infinite. Vieweg, 1995, p. 10, Iyengar was the name of a caste that was a branch of the South Indian Brahmins.

- ↑ Robert Kanigel: Who knew the infinite. Vieweg 1995, p. 10

- ↑ Robert Kanigel: Who knew the infinite. 1995, p. 11

- ↑ Robert Kanigel: Who knew the infinite. 2nd edition, Vieweg, 1995, p. 24

- ↑ imsc.res.in , accessed on March 28, 2020

- ↑ imsc.res.in , accessed on March 28, 2020

- ↑ Robert Kanigel: Who knew the infinite. 2nd edition, Vieweg, 1995, p. 69

- ↑ Robert Kanigel: Who knew the infinite. 2nd edition, Vieweg, 1995, p. 77

- ↑ PV Seshu Iyer: The Late Mr. Srinivasa Ramanujan, BA, FRS June 1920. In: Journal of the Indian Mathematical Society 12 (3). 83. Quoted from Robert Kanigel: Who knew the infinite. 2nd edition, Vieweg, 1995, p. 81

- ↑ The letter is reprinted in Hardy et al. a. (Ed.), Ramanujan, Collected Papers, Cambridge UP 1927, pp. XXIII-XXVII.

- ↑ Robert Kanigel: Who knew the infinite. Vieweg 1995, pp. 141, 142

- ↑ Robert Kanigel: Who knew the infinite. 2nd edition, Vieweg, 1995, p. 146

- ↑ Hardy describes his reaction to the letter in: Hardy, Ramanujan , Cambridge UP 1940, pp. 8–9

- ↑ Hardy, Ramanujan, 1940, p. 9

- ↑ Hardy: "The series formulas ... I found much more intriguing, and it soon became obvious that Ramanujan must posess much more general theorems and was keeping a great deal up his sleave." In Hardy: Ramanujan. 1940, p. 9.

- ↑ After Hardy, Ramanujan, 1940, p. 9. This refers to Bailey: Generalized Hypergeometric Series, Cambridge UP 1932

- ↑ Robert Kanigel: Who knew the infinite. 2nd edition, Vieweg, 1995, p. 148

- ^ Dougall-Ramanujan-Identity, Mathworld

- ↑ Hardy: “I had never seen anything in the least like them before. A single look at them is enough to show that they could only have been written down by a mathematician of the highest class. They must be true because, if they were not true, no one would have had the imagination to invent them. Finally (you must remember that I knew nothing whatever about Ramanujan, and had to think of every possibility), the writer must be completely honest, because great mathematicians are commoner than thieves or humbugs of such incredible skill. ”In Hardy: Ramanujan. 1940, p. 9.

- ↑ a b Hardy: Obituary, S. Ramanujan , Nature, Volume 105, 1920, pp. 494-495.

- ↑ Eric Harold Neville: Srinivasa Ramanujan , Nature, Volume 149, 1942, pp. 292-295.

- ↑ Robert Kanigel: Who knew the infinite. 2nd edition, Vieweg, 1995, p. 153

- ↑ Robert Kanigel: Who knew the infinite. 2nd edition, Vieweg, 1995, p. 156

- ↑ Robert Kanigel: Who knew the infinite. 1995, p. 115

- ↑ Robert Kanigel: Who knew the infinite. 1995, p. 180

- ↑ Hardy's rooms were in the New Court right next to (from inside the New Court on the right) the west portal, which led to an avenue over the River Cam, in stairway A on the second floor. The Bishop's Hostel, in which Ramanujan lived, was directly east on New Court. Ramanujan's first apartment on Whewells Court was east directly opposite the Great Court of Trinity College, northeast of New Court, on the other side of Trinity Street. See the map in Robert Kanigel: Who Knew the Infinite. 1995, front pages and p. 179 (on Hardy's rooms)

- ↑ Robert Kanigel: Who knew the infinite. 1995, p. 179

- ^ "I can believe that he is at least a Jacobi." Letter to Hardy 1913.

- ^ Godfrey Harold Hardy: Collected Papers of GH Hardy. Cambridge UP 1927, pp. XXXV.

- ↑ Robert Kanigel: Who knew the infinite. Vieweg 1995, p. 226

- ↑ Biography of the University of St Andrews, Scotland , accessed April 4, 2020

- ↑ Ramanujan: On highly composite numbers. Proc. London Math. Soc., Series 2, Vol. 14, 1915, pp. 347-400. For financial reasons Ramanujan's essay could not be published in full at the time; the unpublished material appeared in Ramanujan: The lost notebook and other unpublished papers. Narosa Publ. House, Springer, New Delhi 1988 and in Jean-Louis Nicholas, Guy Robin (Editor and Notes), Ramanujan: Highly composite numbers. Ramanujan Journal, Volume 1, 1997, pp. 119-153, PDF.

- ^ "I owe more to him as to anyone else in the world with one exception, and my association with him is the one romantic incident in my life." In Hardy: Ramanujan. Cambridge University Press, 1940, p. 2.

- ↑ "Like all Indians he is fatalistic, and it is terribly hard to get him to take care of himself." Quoted in mathshistory.st-andrews.ac.uk. Accessed April 4, 2020.

- ↑ Kanigel, who knew the infinite, Vieweg 1995, p. 257 f.

- ↑ Robert Kanigel: Who knew the infinite. Vieweg 1995, p. 241

- ↑ Robert Kanigel: Who knew the infinite. Vieweg 1995, p. 261. The information on Ramanujan's suicide and the date come from the notes of S. Chandrasekhar. Others give the second half of 1917 for the suicide attempt. Kanigel, p. 336

- ↑ Robert Kanigel: Who knew the infinite. 2nd edition, Vieweg, 1995, p. 274, note p. 336

- ↑ Robert Kanigel: Who knew the infinite. 2nd edition, Vieweg, 1995, p. 277.

- ↑ Robert Kanigel: Who knew the infinite. 2nd edition, Vieweg, 1995, p. 282.

- ↑ Robert Kanigel: Who knew the infinite. 1995, p. 285.

- ↑ Robert Kanigel: Who knew the infinite. 1995, p. 292.

- ↑ Robert Kanigel: Who knew the infinite. 1995, p. 292

- ↑ Ramanujan´s wife Janakiammal (Janaki). PDF.

- ↑ S. Ramanujan : Modular equations and approximations to . Quarterly Journal of Mathematics, Volume 45, 1914, pp. 350-372 , accessed April 18, 2020 .

- ↑ Jonathan Borwein , Peter Borwein , DH Bailey, Ramanujan: Modular equations and approximations to pi or how to compute one billion digits of pi. (PDF) American Mathematical Monthly, Volume 96, 1989, pp. 201-219 , accessed April 18, 2020 .

- ↑ Calculation at Wolfram Alpha results in a difference of the order of 10 −72 .

- ↑ Hardy, Ramanujan: Asymptotic Formulas in Combinatory Analysis. Proc. London Math. Soc., Volume 17, 1918, pp. 75-115, ( ramanujan.sirinudi.org PDF).

- ↑ Robert Kanigel: Who knew the infinite. 2nd edition, Vieweg, 1995, p. 77

- ↑ a b Eric W. Weisstein : Ramanujan Continued Fractions . In: MathWorld (English).

- ↑ Kanigel: The man who knew infinity. P. 218.

- ^ Letter from Hardy to Ramanujan of March 26, 1913. After Bruce Berndt, Robert Rankin: Ramanujan, Letters and Commentary. AMS p. 77.

- ^ "The analytical theory of numbers is one of those exceptional branches of mathematics in which proof really is everything and nothing short of absolute rigor counts." In Hardy: Ramanujan. 1940, p. 19.

- ↑ Littlewood: A mathematician's miscellany. Methuen 1953, p. 87, review of Ramanujan's Collected Papers.

- ↑ a b Hardy, in: Collected Papers of Srinivasa Ramanujan. Cambridge University Press, 1927, pp. XXXV.

- ↑ a b Hardy in: Ramanujan, Collected Papers. 1927, p. XXXV.

- ↑ Hardy: “ My belief is that all mathematicians think, at bottom, in the same kind of way, and that Ramanujan was no exception. ”

- ↑ Littlewood: A mathematician's miscellany. Hardy, on the other hand, wrote (Ramanujan, 1940, p. 10) that he did not know exactly where Ramanujan's knowledge in this area came from and whether he had read Greenhill or Cayley and regretted not having asked Ramanujan at the time.

- ^ “ Analysis proper Ramanujan's work is less impressive, since he knew no theory of functions, and you cannot do real analysis without it. ”In Hardy: Ramanujan. 1940, p. 14.

- ↑ “ He was by far the greatest formalist of his time, ” even if the “great days of formulas” in mathematics were over 100 years ago. In Hardy: Ramanujan, Collected Papers. 1927, p. XXXV. Quoted again and confirmed by Hardy in Hardy: Ramanujan. 1940, p. 14.

- ↑ "... during his five unfortunate years, his genius was misdirected, sidetracked and distorted to an certain extent." In Hardy: Ramanujan. 1940, p. 6.

- ↑ Hardy in: Ramanujan, Collected Papers. 1927, p. XXXVI.

- ↑ Hardy later dismissed this addition from his foreword to Ramanjan's Collected Papers in his book Ramanujan from 1940, p. 7, albeit as a ridiculous sentimentality on his part.

- ^ The Hardy-Ramanujan Number. ( Memento of May 28, 2013 in the Internet Archive ).

- ^ Hardy in Hardy et al. a. (Ed.), Ramanujan, Collected Works, 1927, p. XXXV, again cited by Hardy in Hardy, Ramanujan 1940, p. 12

- ↑ Robert Kanigel: Who knew the infinite. 2nd edition, Vieweg, 1995, p. 276.

- ↑ Robert Kanigel: Who knew the infinite. 2nd edition, Vieweg, 1995, p. 191.

- ↑ Hardy in: Ramanujan, Collected Papers. 1927, p. XXXI, on his non-mathematical interests.

- ↑ Hardy in: Collected Papers. S. XXV.

- ↑ Srinivasa Ramanujan: Manuscript Book 1 of Srinivasa Ramanujan. (PDF) School of Mathematics, accessed April 11, 2020 .

- ↑ Hardy's estimate, confirmed by Berndt. Berndt: An overview of Ramanjuans notebooks. PDF. Thereafter there were 3254 results in the notebooks, with room for interpretation in the count. According to Berndt, at least half of the results were new (not just a third, as Hardy estimated).

- ↑ apart from about 10 to 20 results that contained a sketch of evidence (Berndt), sometimes consisting of only one sentence.

- ↑ The history of the notebooks is presented in the preface to the edition by Berndt and Andrews. See also Berndt: An overview of Ramanjuans notebooks. PDF.

- ^ "Raiders of the Lost Notebook". English text about trying to prove the formulas in the notebooks.

- ↑ "Ramanujan Machine": Computer with legendary math intuition. Spectrum July 10, 2019.

- ↑ Frank Calegari, The Ramanujan machine as intellectual fraud, Calegari's blog , July 17, 2019, accessed August 1, 2019

- ↑ Minor Planet Circ. 15261.

- ↑ Lambeau depicts R. as a simple man without any schooling who only came across an old math book in adulthood

- ↑ Amita Ramanujan in the US TV series Numb3rs.

- ↑ Ulrich Möller-Arnsberg: The Munich Biennale 1998. The own in the foreign - the foreign in the own. (No longer available online.) In: GEMA -Nachrichten June 157 , 1998, archived from the original on January 7, 2002 ; Retrieved December 2, 2010 .

- ↑ Ramanujan in the Internet Movie Database (English)

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Ramanujan, Srinivasa |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Ramanujan Iyengar, Srinivasa; Ramanujan, S. |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Indian mathematician |

| DATE OF BIRTH | December 22, 1887 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Erode |

| DATE OF DEATH | April 26, 1920 |

| Place of death | Chetpet , Madras |

![{\ frac {1} {\ displaystyle 1 + {\ frac {e ^ {- 2 \ pi {\ sqrt {5}}}} {\ displaystyle 1 + {\ frac {e ^ {- 4 \ pi {\ sqrt {5}}}} {\ displaystyle 1 + {\ frac {e ^ {- 6 \ pi {\ sqrt {5}}}} {\ ddots}}}}}}}} = {\ Biggl (} {\ frac {\ sqrt {5}} {1 + {\ sqrt [{5}] {5 ^ {\ frac {3} {4}} ({\ frac {{\ sqrt {5}} - 1} {2} }) ^ {\ frac {5} {2}} - 1}}}} - {\ frac {{\ sqrt {5}} + 1} {2}} {\ Biggr)} \ cdot e ^ {2 \ pi / {\ sqrt {5}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c41da971d02765113d356784a880b181ab0d417a)