Circle number

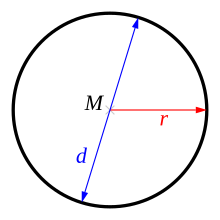

The circle number ( Pi ), also Ludolph number, Ludolf number or Archimedes constant , is a mathematical constant that indicates the ratio of the circumference of a circle to its diameter . This ratio is the same for all circles regardless of size.

The circle number is a transcendent and therefore also an irrational number . Its decimal expansion begins with being in practice often only three significant digits are used: .

The circle number occurs not only in geometry , but is also important in other mathematical sub-areas and theories . For example, they can be used to link the solution of the classic Basel problem with the theory of Fourier series .

Since August 14, 2021 approximately 62.8 trillion decimal places of the decimal representation of the mathematical constant known.

History of the designation

The name with the Greek letter Pi ( ) (after the first letter of the Greek word περιφέρεια - Latin peripheria , "edge area" or περίμετρος - perimetros , "circumference") was first used by William Oughtred in his 1647 published Theorematum in libris Archimedis de Sphæ & Cylyndro Declaratio used. In it he expressed the ratio of half the circumference (semiperipheria) to the radius (semidiameter) , i.e. H.

The English mathematician Isaac Barrow used the same names around 1664 .

David Gregory took (1697) for the circumference to radius ratio.

59 years later than Oughtred, namely in 1706, the Welsh mathematician William Jones was the first to use the Greek lowercase letter in his Synopsis Palmariorum Matheseos to express the ratio of circumference to diameter .

It was only popularized in the 18th century by Leonhard Euler . He first used it for the circle number in 1737 , having previously used it. Since then, due to the meaning of Euler, this designation has been common.

definition

There are several equivalent approaches to defining the circle number .

- The first (classic!) Definition in geometry is that according to which the circle number is a ratio that numerically corresponds to the quotient formed from the circumference of a circle and the associated diameter .

- The second approach to geometry is related to this and consists in understanding the number of circles as the quotient that is formed from the area of a circle and the area of a square over a radius ( length ) . (This radius is called the radius of a circle. ) This second definition is summarized in the motto that a circular area is related to the surrounding square area as .

- In analysis (according to Edmund Landau ) one often proceeds as follows: first of all, the real cosine function is defined via its Taylor series and then the circle number is defined as twice the smallest positive zero of the cosine.

- Further analytical approaches go back to John Wallis and Leonhard Euler .

properties

Irrationality and transcendence

The number is an irrational number , i.e. a real , but not a rational number . This means that it cannot be represented as a ratio of two whole numbers , i.e. not as a fraction . This was proven by Johann Heinrich Lambert in 1761 (or 1767) .

In fact, the number is even transcendent , which means that there is no polynomial with rational coefficients that has as a zero . This was first proven by Ferdinand von Lindemann in 1882. As a consequence, it follows that it is impossible to express only with whole numbers or fractions and roots, and that the exact squaring of the circle with compasses and ruler is not possible.

The first 100 decimal places

Since is an irrational number , its representation cannot be fully specified in any place value system : The representation is always infinitely long and not periodic . With the first 100 decimal places in the decimal fraction development

no regularity is evident. Statistical tests for randomness also suffice with further decimal places (see also the question of normality ).

Representation to other number bases

In the binary system is expressed

- (See OEIS episode OEIS: A004601 ).

The numbers of the representations for bases 3 to 16 and 60 are also given in OEIS.

Continued fraction development

An alternative way to represent real numbers is the continued fraction expansion . Since is irrational, this representation is infinitely long. The regular continued fraction of the circle number begins like this:

A development of related to the regular continued fraction expansion is that of a negative regular continued fraction (sequence A280135 in OEIS ):

In contrast to Euler's number , no patterns or regularities could be found in the regular continued fraction representation of .

However, there are non-regular continued fraction representations of in which simple laws can be recognized:

Approximate fractions of the circle number

From their regular continued fraction representation, the following are the best approximate fractions of the circle number (numerator sequence A002485 in OEIS or denominator sequence A002486 in OEIS ):

| step | Chain fraction | Approximation break | Decimal notation (wrong digits in red) |

Absolute error when calculating the circumference of a circle with a diameter of 1000 km |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| - 141.59 km | ||||

| + 1.26 km | ||||

| - 83.22 m | ||||

| + 26.68 cm | ||||

| - 0.58 mm | ||||

| + 0.33 mm | ||||

| - 0.4 µm (wavelength of blue light ) |

||||

| - 2.6 · 10 −16 m (smaller than a proton ) |

||||

The absolute error in practice quickly becomes negligible: With the 20th approximation, 21 decimal places match those of the circle number . With this approximate fraction, the circumference of a circle with a diameter of around 3.8 quadrillion km (which corresponds to the distance to the Pole Star ) would be incorrectly calculated by one millimeter (namely too short).

Spherical geometry

The term circle number is not used in spherical geometry, since the ratio of circumference to diameter in this case is no longer the same for all circles, but depends on their size. For a circle with a much smaller diameter than that of the sphere on whose surface it is "drawn" (for example a circle with a diameter of 1 m on the spherical surface of the earth), the curvature of the spherical surface compared to the Euclidean circular plane is usually negligibly small, at larger circles or high precision requirements, it must be taken into account.

normality

It is still open whether it is a normal number , that is, whether its binary (or any other n-ary ) number representation equally contains every possible finite binary or other group of digits - as statistics would lead us to expect if we were to find a number perfectly randomly generated. Conversely, it would also be conceivable, for example, that at some point only two digits will appear in an irregular sequence.

If is a normal number, then its (only theoretically possible) complete value representation contains all conceivable patterns, for example all books written so far and in the future in coded binary form (analogous to the Infinite Monkey Theorem ).

In 2000, Bailey and Crandal showed with the Bailey-Borwein-Plouffe formula that the normality from base 2 can be reduced to a conjecture of chaos theory .

In 2005, physicists at Purdue University examined the first 100 million decimal places of for their randomness and compared them with commercial random number generators . The researcher Ephraim Fischbach and his colleague Shu-Ju Tu could not discover any hidden patterns in the number . According to Fischbach, the number is actually a good source of randomness. However, some random number generators performed even better than .

The best-known “randomness” in the sequence of digits is the Feynman point , a sequence of six nines from the 762nd decimal place. This is amazing because, among the first 1000 decimal places, there are only five exact triple sequences and no exact four- or five-fold sequences at all. The second six-fold sequence begins at the 193,034-th decimal place and consists of nines again.

Development of calculation methods

The need to determine the circumference of a circle from its diameter or vice versa arises in very practical everyday life - you need such calculations for fitting a wheel, for fencing in round enclosures, for calculating the area of a round field or the volume of a cylindrical granary. Therefore, people looked for the exact circle number early on and made more and more accurate estimates.

Finally, the Greek mathematician Archimedes succeeded in around 250 BC. To limit the number mathematically. In the further course of the story, the attempts to get as close as possible to a real record hunt at times became bizarre and even self-sacrificing features.

First approximations

Calculations and Estimates in the Pre-Christian Cultures

The circle number and some of its properties were already known in ancient times. The oldest known arithmetic book in the world, the ancient Egyptian arithmetic book of Ahmes (also Papyrus Rhind, 16th century BC), names the value which deviates from the actual value by only around 0.60%.

As an approximation for the Babylonians just used 3 or the rough Babylonian value 3 can also be found in the biblical description of the water basin that was created for the Jerusalem temple :

“Then he made the sea. It was cast from bronze and measured ten cubits from edge to edge; it was perfectly round and five cubits high. A cord of 30 cubits could span it all around. "

The value 3 was also used in ancient China . In India one took for the circle number in the Sulbasutras , the string rules for the construction of altars, the value and a few centuries BC. Chr. In astronomy the approximate value Indian mathematician and astronomer Aryabhata is 498 n. Chr., The ratio of the circumference to the diameter with at.

Approximations for practical everyday life

In times before slide rules and pocket calculators, craftsmen used the approximation and used it to calculate a lot in their heads. The error opposite is about 0.04%. In most cases this is within the possible manufacturing accuracy and is therefore completely sufficient.

Another often used approximation is the fraction , after all, accurate to seven places. All these rational approximate values for have in common that they correspond to partial evaluations of the continued fraction expansion of , e.g. B .:

Archimedes of Syracuse

The approach: constant ratio when calculating area and circumference

Archimedes of Syracuse proved that the circumference of a circle is related to its diameter in the same way as the area of the circle is related to the square of the radius. The respective ratio therefore gives the circle number in both cases. For Archimedes, and for many mathematicians after him, it was unclear whether the calculation of would not come to an end at some point, i.e. whether it would be a rational number, which makes the centuries-long hunt for the number understandable. Although the Greek philosophers knew the existence of such numbers because of the irrationality of , Archimedes had no reason to exclude a rational representation of the area calculation for a circle from the outset . Because there are surfaces that are curvilinearly delimited on all sides, which are even enclosed by parts of a circle, which can be represented as a rational number like the little moon of Hippocrates .

It was not until 1761/1767 that Johann Heinrich Lambert was able to prove the long suspected irrationality of .

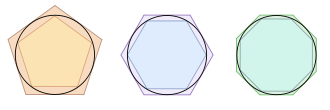

Approximation by polygons

Archimedes, like other researchers, tried to approximate the circle with regular polygons and in this way to gain approximations for . With circumscribed and inscribed polygons, starting with hexagons, by repeatedly doubling the number of corners up to 96 corners, he calculated upper and lower bounds for the circumference. He came to the conclusion that the ratio had to be a little smaller than , but larger than :

According to Heron , Archimedes had an even more precise estimate, but it has been passed down incorrectly:

Wilbur Knorr corrected:

4th to 15th century

As in many other areas of society and culture, mathematics in western cultures experienced a very long period of standstill after the end of antiquity and during the Middle Ages. During this time, progress in approaching was made primarily by Chinese and Persian scientists.

In the third century, Liu Hui determined the limits 3.141024 and 3.142704 from the 192-corner and later the approximate value 3.1416 from the 3072-corner.

The Chinese mathematician and astronomer Zu Chongzhi (429–500) calculated around 480 for the circle number , ie the first 7 decimal places. He was also familiar with the almost equally good approximate fraction (this is the third approximate fraction of the continued fraction expansion of ), which was only found in Europe in the 16th century ( Adriaan Metius , therefore also called the Metius value). In the 14th century, Zhao Youqin calculated the number of circles to six decimal places using a 16384 corner.

In his treatise on the circle , which he completed in 1424, the Persian scientist Jamschid Masʿud al-Kaschi calculated a 3 × 2 28 corner with an accuracy of 16 digits.

16th to 19th century

In Europe , Ludolph van Ceulen succeeded in calculating the first 35 decimal places of in 1596 . Allegedly he sacrificed 30 years of his life for this calculation. Van Ceulen, however, has not yet contributed any new ideas to the calculation. He simply continued to calculate according to Archimedes' method, but while Archimedes stopped at the ninety-six corner, Ludolph continued the calculations up to the inscribed corner . The name Ludolph's number is a reminder of his achievement.

The French mathematician François Viète varied the Archimedean exhaustion method in 1593 by approximating the area of a circle using a series of inscribed corners . From this he was the first to derive a closed formula for in the form of an infinite product :

The English mathematician John Wallis developed the Valais product named after him in 1655 :

In 1655 Wallis showed this series to Lord Brouncker , the first President of the “ Royal Society ”, who represented the equation as a continued fraction as follows:

Gradually the calculations became more complicated, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz contributed the following series representation in 1682 :

See also calculation of district numbers according to Leibniz .

This was known to Indian mathematicians as early as the 15th century. Leibniz rediscovered it for European mathematics and proved the convergence of this infinite sum. The above series is also a special case ( ) of the series expansion of the arctangent that the Scottish mathematician James Gregory found in the 1670s:

In the following time it was the basis of many approximations of , all of which have a linear speed of convergence .

In 1706 William Jones described in his work Synopsis palmariorum matheseos the series developed by him, with which he determined 100 decimal places of .

"Let [...] Then & c."

Also in 1706, John Machin calculated the first 100 decimal places of with his formula . His equation

can be used together with the Taylor series expansion of the arctangent function for fast calculations. In the real world, this formula can be obtained using the arctangent's addition theorem; it is simpler by considering the argument of the complex number

Over time, more formulas of this type have been found. An example comes from FCW Størmer (1896):

which is synonymous with the fact that the real and imaginary parts of the Gaussian number

- with

are the same.

In his Introductio in Analysin Infinitorum , published in 1748, Leonhard Euler already quoted 148 places in the first volume . Formulas discovered by Euler (see also Riemann ζ function ):

Johann Heinrich Lambert published a continued fraction in 1770, which is mostly in the form today

is written. Each step results in an average of around 0.76555 decimal places, which is relatively high compared to other continued fractions.

Numerical methods from the 20th century

In the 20th century, iteration methods were developed that allow a much more efficient calculation of "new" decimal places.

In 1914 the Indian mathematician Srinivasa Ramanujan found the following formula while investigating elliptical functions and modular functions :

The first iterations of this procedure produce the following results:

| Iterations | gives expression | corresponds to decimal (wrong digits in red) |

|---|---|---|

So the root of 2 is multiplied with increasingly “longer” fractions. This method provides about 8 more correct decimal places per iteration.

Chudnovsky algorithm

More efficient methods became interesting with the development of computers with long number arithmetic , because the pure computational effort became less and less important and complicated iteration methods with quadratic or even higher convergence became practicable.

The Chudnovsky algorithm, published in 1988, is the fastest currently known method and has been used in all current record calculations. It was developed from the Ramanujan approach, but works about 50 percent faster, and is based on the convergence of a generalized hypergeometric series :

The software y-cruncher offers a technical implementation of both iteration methods (Ramanujan and Chudnovsky) .

BBP series

In 1995, Simon Plouffe, together with Peter Borwein and David Harold Bailey, discovered a new type of series representation for :

This series (also called Bailey-Borwein-Plouffe formula) enables the -th digit of a binary, hexadecimal or any representation to be calculated to a power of two without first having to calculate the previous digits.

Later the following were found for other BBP series:

Drip algorithm

Closely related to digit extraction methods are drip algorithms in which the digits are calculated one after the other. Stanley Rabinowitz found the first such algorithm for calculating . Since then, more drip algorithms have been found to calculate .

Method of Gauss, Brent and Salamin

The calculation of the arc length of a lemniscate using elliptic integrals and its approximation using the arithmetic-geometric mean according to Gauss provides the rapidly converging method of Salamin and Brent for numerical calculation. The basis for this is the following representation, initially assumed by Gauss :

The latter integral is also known as the lemniscatic constant . It then applies

where is the arithmetic-geometric mean over the iteration

is calculated with two initial arguments , and is set.

Non-numerical calculation methods

Calculation using the area formula

This calculation uses the relationship that the area formula contains the circle, but not the area formula of the circumscribing square.

The formula for the area of the circle with radius is

- ,

the area of the square with side length is calculated as

- .

For the ratio of the area of a circle and its circumscribing square, the result is

- .

This can be written as four times this ratio:

- .

program

As an example, an algorithm is given in which the area formula is demonstrated, with which an approximate calculation can be made.

To do this, you put a grid over the square and calculate for each individual grid point whether it is also in the circle. The ratio of the grid points within the circle to the grid points within the square is multiplied by 4. The accuracy of the obtained approximation depends on the grid width and is controlled by. With you get z. B. 3.16 and with already 3.1428. For the result 3.14159, however, one has to set what is reflected in the two-dimensional approach to the number of necessary arithmetic operations in square form.

r = 10000

kreistreffer = 0

quadrattreffer = r ^ 2

for i = 0 to r - 1

x = i + 0.5

for j = 0 to r - 1

y = j + 0.5

if x ^ 2 + y ^ 2 <= r ^ 2 then

kreistreffer = kreistreffer + 1

return 4 * kreistreffer / quadrattreffer

Note: The above program has not been optimized for the fastest possible execution on a real computer system, but has been formulated as clearly as possible for reasons of clarity. Furthermore, the circular area is determined imprecisely in that it is not the coordinates of the center that are used for the respective area units, but the area edge. By considering a full circle, the area of which tends towards zero for the first and last lines, the deviation for large ones is marginal.

The constant Pi is typically already pre-calculated for everyday use in computer programs; the associated value is usually given with slightly more digits than the most powerful data types of this computer language can accept.

Alternative program

This program adds up the area of the circle from strips that are very narrow in relation to the radius. It uses the equations and as well .

n := 1000000 // Halbe Anzahl der Streifen

s := 0 // Summe der Flächeninhalte

for x := -1 to +1 step 1/n:

// Flächeninhalt des Streifens an der Stelle x hinzuaddieren.

// Die Höhe des Streifens wird exakt in der Mitte des Streifens gemessen.

// Die 2 steht für die obere plus die untere Hälfte.

// Der Faktor 1/n ist die Breite des Streifens.

s += 2 * sqrt(1 - x*x) * 1/n

pi := s

The x-coordinates of the examined area go from to . Since circles are round and this circle has its center on the coordinates , the y-coordinates are also in the range from to . The program divides the area to be examined into 2 million narrow strips. Each of these strips has the same width, viz . However, the top edge of each strip is different and results from the above formula , in the code this is written as . The height of each strip goes from the top edge to the bottom edge. Since the two edges of circles are equidistant from the center line, the height is exactly twice the edge length, hence the 2 in the code.

sqrt(1 - x*x)

After running through the for loop, the variable s contains the area of the circle with radius 1. In order to determine the value of Pi from this number, this number has to be divided by according to the formula . In this example , it is omitted from the program code.

Statistical determination

Calculation with a Monte Carlo algorithm

One method of determining is the statistical method . For the calculation you let random points "rain" on a square and calculate whether they are inside or outside an inscribed circle. The proportion of internal points is

This method is a Monte Carlo algorithm ; the accuracy of the approximation of achieved after a fixed number of steps can therefore only be specified with a probability of error . However, due to the law of large numbers , the average accuracy increases with the number of steps.

The algorithm for this determination is:

function approximiere_pi(tropfenzahl)

innerhalb := 0 // Zählt die Tropfen innerhalb des Kreises

// So oft wiederholen, wie es Tropfen gibt:

for i := 1 to tropfenzahl do

// Zufälligen Tropfen im Quadrat [0,0] bis (1,1) erzeugen

x := random(0.0 ..< 1.0)

y := random(0.0 ..< 1.0)

// Wenn der Tropfen innerhalb des Kreises liegt ...

if x * x + y * y <= 1.0

innerhalb++ // Zähler erhöhen

return 4.0 * innerhalb / tropfenzahl

The one 4.0in the code results from the fact that only the number for a quarter circle was calculated in the droplet simulation. In order to get the (extrapolated) number for a whole circle, the calculated number has to be multiplied by 4. Since the number pi is the ratio between the area of the circle and the square of the radius, the number obtained in this way has to be divided by the square of the radius. The radius in this case is 1, so splitting can be omitted.

Buffon's needle problem

Another unusual method based on probabilities is Buffon's needle problem by Georges-Louis Leclerc de Buffon (presented in 1733, published in 1777). Buffon tossed sticks over his shoulder onto a tiled floor. Then he counted the number of times they hit the joints. Jakow Perelman described a more practicable variant in his book Entertaining Geometry. Take a needle about 2 cm long - or some other metal pencil of similar length and diameter, preferably without a point - and draw a series of thin parallel lines on a piece of paper, spaced twice the length of the needle. Then you let the needle fall very often (several hundred or thousand times) from any arbitrary but constant height onto the sheet and note whether the needle intersects a line or not. It doesn't matter how you count the touch of a line through the end of a needle. Divide the total number of needle throws by the number of times the needle has cut a line

- ,

where denotes the length of the needles and the distance between the lines on the paper. This easily gives an approximation for . The needle can also be bent or kinked several times, in which case more than one intersection point per throw is possible and accordingly has to be counted several times. In the middle of the 19th century, the Swiss astronomer Rudolf Wolf achieved a value of by throwing 5,000 needles .

Records of the calculation of

| carried out by | year | Decimal places | Method / aid | Computing time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Archimedes | approx. 250 BC Chr. | 2 | 96-corner | |

| Liu Hui | after 263 | 5 | 3072 corner | |

| To Chongzhi | approx. 480 | 6th | ||

| Jamjid Masʿud al-Kashi | circa 1424 | 15th | 3 · 2 28 corner | |

| Ludolph van Ceulen | 1596 | 20th | ||

| Ludolph van Ceulen | 1610 | 35 | 2 62 corner | |

| William Jones John Machin |

1706 | 100 |

Series Developments William Jones: Let it be then John Machin: |

|

| Jurij Vega | 1794 | 126 | ||

| William Shanks | 1853 | (527) | Series expansion of and . Calculation of the first 707 decimal places by hand. In 1945, John W. Wrench discovered that the last 180 digits were wrong. |

|

| Levi B. Smith, John W. Wrench | 1949 | 1,120 | mechanical adding machine | |

| G. Reitwiesner | 1949 | 2,037 | with the tube calculator ENIAC | 70 h |

| Nicholson, Jaenel | 1954 | 3,092 | Naval Ordnance Research Calculator | 0:13 h |

| George E. Felton | 1957 | 7,480 | Pegasus | 33 h |

| F. Genuys | 1958 | 10,000 | with the magnetic core memory computer IBM 704 , using the Machin formula | 10 h |

| George E. Felton | 1958 | 10,021 | Pegasus | 33 h |

| Jean Guilloud | 1959 | 16,167 | IBM 704 | 4:18 h |

| Daniel Shanks , John W. Wrench | 1961 | 100,265 | with the transistor computer IBM 7090 | 8:43 h |

| Jean Guilloud, J. Filliatre | 1966 | 250,000 | IBM 7030 | 41:55 h |

| Jean Guilloud, M. Dichampt | 1967 | 500,000 | CDC 6600 | 28:10 h |

| Jean Guilloud, Martin Boyer | 1973 | 1.001.250 | CDC 7600 | 23:18 h |

| Kazunori Miyoshi , Yasumasa Canada | 1981 | 2,000,036 | FACOM M-200 | 137: 18 h |

| Jean Guilloud | 1981 | 2,000,050 | ||

| Yoshiaki Tamura | 1982 | 2,097,144 | MELCOM 900II | 7:14 h |

| Yoshiaki Tamura, Yasumasa Canada | 1982 | 4,194,288 | HITAC M-280H | 2:21 h |

| Yoshiaki Tamura, Yasumasa Canada | 1982 | 8,388,576 | HITAC M-280H | 6:52 h |

| Yasumasa Canada, Sayaka Yoshino, Yoshiaki Tamura | 1982 | 16,777,206 | HITAC M-280H | <30 h |

| Yasumasa Canada, Yoshiaki Tamura, Yoshinobu Kubo | 1987 | 134.217.700 | ||

| David and Gregory Chudnovsky | 1989 | 1,011,196,691 | ||

| Yasumasa Canada, Daisuke Takahashi | 1997 | 51,539,600,000 | ||

| Yasumasa Canada, Daisuke Takahashi | 1999 | 206.158.430.000 | ||

| Yasumasa Canada | 2002 | 1,241,100,000,000 | Calculation: Verification: |

|

| Daisuke Takahashi | 2009 | 2,576,980,370,000 | Calculation: Gauss-Legendre algorithm | |

| Fabrice Bellard | 2010 | 2,699,999,990,000 | Calculation: TachusPi software ( Chudnovsky formula , verification: Bellard's formula ) | 131 days |

| Shigeru Kondo, Alexander Yee | 2010 | 5,000,000,000,000 | Calculation: y-cruncher software (Chudnovsky formula, verification: Plouffes and Bellards formula) | 90 days |

| Shigeru Kondo, Alexander Yee | 2011 | 10,000,000,000,050 | Calculation: y-cruncher software (Chudnovsky formula, verification: Plouffes and Bellards formula) | 191 days |

| Shigeru Kondo, Alexander Yee | 2013 | 12.100.000.000.050 | Calculation: y-cruncher software (Chudnovsky formula, verification: Bellard’s formula) | 82 days |

| Sandon Van Ness (Houkouonchi) | 2014 | 13,300,000,000,000 | Calculation: y-cruncher software (Chudnovsky formula, verification: Bellard’s formula) | 208 days |

| Peter Trüb / DECTRIS | 2016 | 22.459.157.718.361 | Calculation: y-cruncher software (Chudnovsky formula, verification: Bellard’s formula) | 105 days |

| Emma Haruka Iwao / Google LLC | 2019 | 31,415,926,535,897 | Calculation: y-cruncher software (Chudnovsky formula, verification: Plouffes and Bellards formula) | 121 days |

| Timothy Mullican | 2020 | 50,000,000,000,000 | Calculation: y-cruncher software (Chudnovsky formula, verification: Plouffes and Bellards formula) | 303 days |

| University of Applied Sciences Graubünden | 2021 | 62,831,853,071,796 | Calculation: y-cruncher software (Chudnovsky formula, verification: Plouffes and Bellards formula) | 108 days |

Geometric constructions

Due to the transcendence of , it is not possible to use a compass and ruler to create a route with the exact length of units of length. However, there are both a number of compass and ruler constructions that provide very good approximations, as well as constructions that enable an exact construction thanks to another aid - in addition to compasses and ruler. A further aid of this kind is in particular curves designated as quadratic indexes which, for. B. generated with the help of a so-called dynamic geometry software (DGS) and printed as a. find use on paper. There are also some special mechanical drawing devices and possibly specially made curve rulers with which such curves can be drawn.

Approximate constructions

For the geometric construction of the number there is the approximate construction by Kochański from 1685, with which one can determine an approximate value of the circle number with an error of less than 0.002 percent. So it is an approximation construction for the (exactly not possible) quadrature of the circle .

143 years later, namely in 1828, CG Specht published his Second Approximation Construction of Circular Circumference in the Journal for Pure and Applied Mathematics. For the approach he found the value

Halving this value results in a decimal number with seven digits after the decimal point the same as those of the circle number :

In the case of a circle with a radius , this value is also equal to the area of the triangle , in other words, the area of the triangle is almost equal to that of the circle.

It is noteworthy that only in 1914, i. H. 86 years later, Srinivasa Ramanujan - in his second squaring of the circle - improved the accuracy of the almost equal square by one to eight decimal places with the circle number

A graphic representation is not recorded in the journal cited above; the editor's note on this:

"*) It will be easy for the reader to design the figure according to the description."

The following description of the adjacent construction is based on the original of the construction description.

First draw the unit circle around the point and then draw a straight line from; it results . Then it is erected in a perpendicular to the straight line; it creates . Four semicircles follow one after the other on the straight line, each with the radius around the newly resulting intersection point, which creates the points and . After the tripartite division of the routes in and as well as in and that point is now with connected. The resulting stretch is removed from the vertical . Connect also the point with and transfer the new route from to the vertical; it surrenders . It continues with the connections of the points with as well as with . When transferring the route to the route ab results . Finally, drawing from a parallel to the route , which in cuts. The resulting distance corresponds approximately to the value .

The approximation to the number of circles can, for. B. be clarified in the following way:

If the diameter were a circle , its approximate circumference would only be approx. Shorter than its theoretical value.

Quadratrix des Hippias as an additional aid

The illustration opposite shows the number of circles as a segment, created with the help of the Quadratrix des Hippias .

It starts with a straight line from the point and a perpendicular to this straight line . Then the semicircle is drawn with the radius around ; this results in the intersections and . Now you construct the square with side length 1. The construction of the quadratrix follows, without a "gap" on the x-axis , with the parameter curve :

with

According to the Dinostratos theorem, the quadratrix cuts the side of its associated square at the point and thus generates the value on the straight line, now used as a number line . Establishing the vertical on the line from to the semicircle results in the intersection . After extending the distance beyond and drawing a straight line from through to the extension, the point of intersection results . One possibility, inter alia. is now to determine the length of the line with the help of the ray theorem. In the drawing it can be seen that the route corresponds. As a result, the proportions of the sections are after the first theorem of rays

transformed and the corresponding values inserted results

Now the arc with the radius is drawn up to the number line; the point of intersection is created . The final Thales circle above from the point gives the exact circle number .

Archimedean spiral as an additional aid

A very simple construction of the circle number is shown in the picture on the right, generated with the help of the Archimedean spiral .

Parameter representation of an Archimedean spiral:

After drawing in the - and - axis of a Cartesian coordinate system, an Archimedean spiral with the parameter curve is created in the coordinate origin :

with becomes the angle of rotation of the spiral

The spiral cuts into the axis and thus delivers after a quarter turn

The semicircle with radius projected onto the axis and the distance (green lines) are only used to clarify the result.

Experimental construction

The following method uses the circle number "hidden" in the circular area in order to represent the value of as a measurable quantity with the help of experimental physics .

A cylinder with the radius and the height of the vessel is filled with water up to the height . The amount of water determined in this way is then transferred from the cylinder into a cuboid , which has a square base with a side length and a vessel height of .

Amount of water in the cylinder in units of volume [VE]:

Water level in the cuboid in units of length [LE]:

- , from it

The result shows: An amount of water that has the water level in a cylinder with the radius delivers the water level when it is poured into the cuboid .

Formulas and Applications

Formulas that contain π

Formulas of geometry

In geometry , the properties of emerge directly as a circle number.

- Perimeter of a circle with a radius :

- Area of a circle with a radius :

- Volume of a sphere with a radius :

- Surface of a sphere with a radius :

- Volume of a cylinder with radius and height :

- Volume one by the rotation of the graph around the defined axis rotational body to the limits and :

Formulas of analysis

In the field of analysis also plays a role in many contexts, for example in

- the integral representation that Karl Weierstrass used in 1841 to define

- of the infinite series : ( Euler , see also Riemann's zeta function ),

- the Gaussian normal distribution : or other representation: ,

- the Stirling formula as an approximation of the Faculty for large : ,

- the Fourier transform : .

- Function theory formulas

As for all sub-areas of analysis, the number of circles is of fundamental importance for function theory (and beyond that for the entire complex analysis ). As prime examples are here

- the Euler identity

to call as well

In addition, the meaning of the circle number is also evident in the formulas for the partial fraction decomposition of the complex-valued trigonometric functions , which are related to the Mittag-Leffler theorem . Here are above all

to mention as well as those from it - among others! - to be won

- Partial fraction decomposition to sine and cosine :

The above partial fraction to the sine then supplies by insertion of the well-known series representation

which in turn directly to Euler's series representation

leads.

In addition to these π formulas resulting from the partial fraction series, function theory also knows a large number of other ones which, instead of the representation with infinite series, have a representation using infinite products . Many of them go back to the work of Leonhard Euler ( see below ).

Number theory formulas

- The relative frequency that two randomly chosen natural numbers , which are below a bound, are coprime , tends to counter this .

Formulas of physics

In physics plays alongside

- the circular motion: (angular velocity is equal to the frequency of rotation )

This is especially important for waves , as the sine and cosine functions are included there; so for example

aside from that

- in the calculation of the buckling load

- and in the friction of particles in liquids ( Stokes law )

Product formulas from Leonhard Euler

- If the sequence of prime numbers is denoted by, as usual , then the following applies:

- The following product formulas can also be traced back to Euler, which connect the circle number with the complex gamma function and the complex sine and cosine :

- The first of the three following formulas is also known as Euler's supplementary theorem . The following two product formulas for sine and cosine are absolutely convergent products. Both product formulas result from the supplementary sentence, with the product formula of the cosine itself being a direct application of the product formula of the sine.

- The product formula of the sine then leads to this interesting relationship (sequence A156648 in OEIS ):

miscellaneous

Curiosities

- Friends of the number celebrate on March 14 (in American notation 3/14) the Pi Day and on July 22 (in American notation 7/22) the Pi Approximation Day .

- In 1897 should be in the US - state of Indiana with the Indiana Pi Bill the circle number be legally placed on one of the values of amateur mathematician Edwin J. Goodwin found that appealed to supernatural inspiration. Different values for the circle number can be derived from his work, including 4 or 16 ⁄ 5 . After offering royalty-free use of his discoveries, the House of Representatives unanimously passed the bill. When Clarence A. Waldo, a math professor at Purdue University , found out about it while visiting parliament and raised an objection, the second house of parliament postponed the draft indefinitely.

- The § 30b of the Road Traffic Licensing Regulations determined in Germany for the calculation of (for road tax relevant) displacement of an engine ". For the value pi is used by 3.1416"

- The version number of the typesetting program TeX by Donald E. Knuth has been incremented, contrary to the usual conventions of software development since the 1990s, so that it slowly approaches. The current version from January 2021 has the number 3.141592653

- The version name of the free geographic information system software QGIS is in version 3.14 "Pi". Additional decimal places are added for bugfix versions.

- Scientists use radio telescopes to send the circle number into space . They feel that if they can pick up the signal, other civilizations need to know this number.

- The current record for reading Pi aloud is 108,000 decimal places in 30 hours. The world record attempt began on June 3, 2005 at 6:00 p.m. and was successfully completed on June 5, 2005 at 0:00 a.m. Over 360 readers read 300 decimal places each. The world record was organized by the Mathematikum in Gießen .

Film, music, culture and literature

- In the novel The Magic Mountain by Thomas Mann , the narrator describes in the chapter The great stupidity on compassionate-belächelnde way as the minor character of the prosecutor Partition the "desperate break" Pi tries to unravel. Paravant believes that “providential planning” determined him to “tear the transcendent goal into the realm of earthly precise fulfillment”. He tries to awaken in his environment a “humane sensitivity to the shame of the contamination of the human spirit by the hopeless irrationality of this mystical relationship”, and asks himself “whether it has not been too difficult for mankind to solve the problem since Archimedes' days and whether this solution is actually the simplest for children. ”In this context, the narrator mentions the historical Zacharias Dase , who calculated pi to two hundred decimal places.

- In episode 43 of the science fiction series Raumschiff Enterprise , The Wolf in Sheep's Clothing (original title Wolf in the Fold ), an alien being seizes the on-board computer. The chief officer Spock then orders the computer to calculate the number pi down to the last decimal place. The computer is so overwhelmed by this task that the being leaves the computer again.

- In 1981, Carl Sagan's book Contact was published. The book describes the SETI program for the search for extraterrestrial intelligence and related philosophical considerations. It ends with the fictitious answer to the question of whether the universe came into being by chance or was systematically created. The number plays the central role for the exciting answer, which is consistent in the context of the plot.

- 1988 initiated Larry Shaw the Pi Day on March 14 at the Exploratorium .

- In 1998 Darren Aronofsky (Requiem for a Dream) released the film Pi , in which a mathematical genius ( Sean Gullette as 'Maximilian Cohen') tries to filter out the world formula .

- In the published 2005 double album Aerial of Kate Bush song of Pi is dedicated.

- The media installation Pi , which opened in November 2006 in the Wiener Opernpassage, is dedicated, among other things, to the circle number.

- In the film Nights in the Museum 2 (2009), the circle number is the combination for the Ahkmenrah table. The combination is solved with the help of Bobble-Head Einstein and opens the gate to the underworld in the film.

- The progressive deathcore band After the Burial released the song Pi (The Mercury God of Infinity) on their debut album Forging a Future Self . It consists of an acoustic guitar solo followed by a breakdown , the rhythm of which is based on the first 110 digits of the circle number.

Pi sport

Memorizing the number pi is the most popular way to demonstrate remembering long numbers. So learning from pi has become a sport. The Indian Rajveer Meena is the official world record holder with a confirmed 70,000 decimal places, which he recited flawlessly on March 21, 2015 in a time of 10 hours. He is listed as a record holder in the Guinness Book of Records.

The unofficial world record was in October 2006 at 100,000 positions, set by Akira Haraguchi . The Japanese broke his also unofficial old record of 83,431 decimal places. Jan Harms holds the German record with 9140 jobs. Special mnemonic techniques are used to memorize Pi . The technique differs according to the preferences and talents of the memory artist and the number of decimal places to be memorized.

There are simple memory systems for memorizing the first digits of Pi, as well as Pi-Sport memorization rules .

Alternative circle number τ

The American mathematician Robert Palais opened in 2001 in an issue of Mathematics Magazine The Mathematical Intelligencer before, for , instead of as the ratio of circumference and diameter of a circle, in the future, the ratio of circumference and radius (equivalent ) to use as a basic constant. His reasoning is based on the fact that the factor appears before the circle number in many mathematical formulas . Another argument is the fact that the new constant in radians represents a full angle instead of a half angle, making it less arbitrary. The newly standardized circle number, for whose notation Michael Hartl and Peter Harremoës suggested the Greek letter (Tau), would shorten these formulas. With this convention shall be considered , therefore .

literature

- Jörg Arndt, Christoph Haenel: Π [Pi] . Algorithms, computers, arithmetic. 2nd, revised and expanded edition. Springer Verlag, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-540-66258-8 (with CD-ROM , 1st edition. 1998 - without CD-ROM, ISBN 3-540-63419-3 ).

- Heinrich Behnke , Friedrich Sommer : Theory of the analytical functions of a complex variable (= The basic teachings of the mathematical sciences in individual representations . Volume 77 ). Springer-Verlag, Berlin / Heidelberg / New York 1965.

- Petr Beckmann: A History of π . St. Martin's Press, New York City 1976, ISBN 978-0-312-38185-1 (English).

- Ehrhard Behrends (ed.): Π [Pi] and co . Kaleidoscope of mathematics. Springer, Berlin / Heidelberg 2008, ISBN 978-3-540-77888-2 .

- David Blatner: Π [Pi] . Magic of a number. In: rororo non-fiction book (= rororo . No. 61176 ). Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2001, ISBN 3-499-61176-7 (original title: The Joy of Π [pi] . Translated by Hainer Kober).

- Jonathan Borwein , Peter Borwein : Pi and the AGM . A Study in Analytic Number Theory and Computational Complexity. In: Canadian Mathematical Society Series of Monographs and Advan . 2nd Edition. Wiley, New York NY 1998, ISBN 0-471-31515-X (English).

- Egmont Colerus : From multiplication tables to integral . Mathematics for Everyone (= Rowohlt-fiction book . No. 6692 ). Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 1974, ISBN 3-499-16692-5 .

- Jean-Paul Delahaye : Π [Pi] . The story. Birkhäuser, Basel 1999, ISBN 3-7643-6056-9 .

- Keith Devlin : Great moments of modern mathematics . famous problems and new solutions (= dtv-Taschenbuch 4591 ). 2nd Edition. Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, Munich 1992, ISBN 3-423-04591-4 (Original title: Mathematics . Translated by Doris Gerstner, license from Birkhäuser-Verlag, Basel).

- Leonhard Euler: Introduction to the Analysis of the Infinite . Springer Verlag, Berlin / Heidelberg / New York 1983, ISBN 3-540-12218-4 (first part of the Introductio in Analysin Infinitorum - reprint of the Berlin 1885 edition).

- Eberhard Freitag , Rolf Busam : Function theory 1 (= Springer textbook ). 3rd, revised and expanded edition. Springer Verlag, Berlin (inter alia) 2000, ISBN 3-540-67641-4 .

- Klaus Jänich : Introduction to Function Theory . 2nd Edition. Springer-Verlag, Berlin (inter alia) 1980, ISBN 3-540-10032-6 .

- Paul Karlson: On the magic of numbers . Fun math for everyone. In: The modern non-fiction book . 8th, revised edition. tape 41 . Ullstein, Berlin 1965 (without ISBN , previous title: You and the magic of numbers ).

- Karel Markowski: The calculation of the number Π [(Pi)] from sine and tangent intervals . 1st edition. Trigon, Potsdam 2007, ISBN 978-3-9810752-1-2 .

- Konrad Knopp : Theory and Application of the Infinite Series (= The Basic Teachings of Mathematical Sciences . Volume 2 ). 5th, corrected edition. Springer Verlag, Berlin (inter alia) 1964, ISBN 3-540-03138-3 .

- Konrad Knopp: Function Theory II . Applications and continuation of the general theory (= Göschen Collection . Volume 703 ). 11th edition. de Gruyter, Berlin 1965.

- Herbert Meschkowski : Infinite rows . 2nd, improved and enlarged edition. BI Wissenschaftsverlag, Mannheim (inter alia) 1982, ISBN 3-411-01613-2 .

- Jakow Perelman : Entertaining Geometry . People and Knowledge, Berlin 1962.

- Jürgen Petigk: Triangular circles or how you can determine Π [Pi] with a needle . Math puzzles, brain training. Komet, Cologne 2007, ISBN 978-3-89836-694-6 (published in 1998 as Mathematics in Leisure Time by Aulis-Verlag Deubner, Cologne, ISBN 3-7614-1997-X ).

- Karl Helmut Schmidt: Π [Pi] . History and algorithms of a number. Books on Demand GmbH, Norderstedt, ISBN 3-8311-0809-9 ([2001]).

- Karl Strubecker : Introduction to higher mathematics. Volume 1: Basics . R. Oldenbourg Verlag, Munich 1956.

- Heinrich Tietze : Mathematical Problems . Solved and unsolved math problems from old and new times. Fourteen lectures for amateurs and friends of mathematics. CH Beck, Munich 1990, ISBN 3-406-02535-8 (special edition in one volume, 1990 also as dtv paperback 4398/4399, ISBN 3-423-04398-9 - volume 1 and ISBN 3-423-04399-7 - Part 1).

- Fridtjof Toenniessen : The secret of the transcendent numbers . A slightly different introduction to math. 2nd Edition. Springer Verlag, Berlin 2019, ISBN 978-3-662-58325-8 , doi : 10.1007 / 978-3-662-58326-5 .

- Claudi Alsina, Roger B. Nelsen: Charming Proofs: A Journey Into Elegant Mathematics . MAA 2010, ISBN 978-0-88385-348-1 , pp. 145-146 ( excerpt (Google) )

Web links

- Proof of the irrationality of mathematics in the formulary

- Proof of the transcendence of and in the evidence archive.

- Albrecht Beutelspacher (Mathematikum Gießen): Mathematics to touch - The number . Bavaria α.

- Werner Scholz: The history of number approximations. TU Vienna, November 3, 2001.

- Archimedes and the determination of the circle number.

- The -Search Page. Searchdigit sequences within.

- Pibel.de. The number Pi with up to 10 million decimal places is available for download on this website.

- Current world ranking of memorizers. English.

- Monte Carlo method for approximating π.

- Don Zagier : Number theory and the circle number Pi. Gauss lecture 2003 in Freiburg (podcast).

Remarks

- ↑ Mathematically strictly applies .

- ↑ A simple proof of irrationality was provided in 1947 by the number theorist Ivan Niven . (Ivan Niven: A simple proof that π is irrational . In: Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society . Volume 53 , 1947, pp. 509 ( MR0021013 ). )

- ↑ Here all partial counters are equal to 1.

- ↑ Here all partial counters are equal to −1.

- ↑ See Bailey's website for more details .

- ↑ This is

- ↑ The Euler identity is seen as a combination of the circle number , the likewise transcendent Euler number , the imaginary unit and the two algebraic base quantities and as one of the “most beautiful mathematical formulas”.

- ↑ The song on YouTube with an explanation of the rhythm in the video description, written by one of the guitarists. Video on YouTube .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Fridtjof Toenniessen: The secret of the transcendent numbers . Springer, 2019, p. 327 ff .

- ↑ Guilelmo [William] Oughtred: Theorematum in libris Archimedis de Sphæra & Cylyndro Declaratio. Rerum quarundam denotationes. In: BSB Bavarian State Library digital. Oughtred, William, Publisher: Lichfield, Oxoniae, 1663, p. 3 , accessed August 21, 2019 (Latin).

- ^ William Oughtred: Theorematum in libris Archimedis de Sphæra & Cylyndro Declaratio. 1663. In: Clavis Mathematicae. Lichfield, Oxford 1667, pp. 201-214, here p. 203.

- ↑ See David Eugene Smith: History of Mathematics. Volume 2. Dover, New York 1953, p. 312 (The Symbol ).

- ^ A b c William Jones: Synopsis Palmariorum Matheseos. Palmariorum Matheseos, p. 243, see middle of page: "1/2 Periphery ( )" with specification of the ratio of half circumference to radius or circumference to diameter to 100 decimal places. In: Göttingen Digitization Center. J. Matthews, London, 1706, accessed August 19, 2019 .

- ↑ William Jones: Synopsis Palmariorum Matheseos. Palmariorum Matheseos, p. 263, see below: “3.14159, & c. = [...] Whence in the Circle, any one of these three, [area] a, [circumference] c, [diameter] d, being given, the other two are found, as, d = c ÷ = ( a ÷ 1 / 4 ) 1/2 , c = d × = ( a × 4 ) 1/2 , a = 1/4 × d 2 = c 2 ÷ 4. "In: Göttinger Digitization Center. J. Matthews, London, 1706, accessed August 19, 2019 .

- ↑ Jörg Arndt, Christoph Haenel: PI: Algorithmen, Computer, Arithmetik . 2nd, revised and expanded edition. Springer, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-540-66258-8 , pp. 8 .

- ↑ Jörg Arndt, Christoph Haenel: PI: Algorithmen, Computer, Arithmetik . 2nd, revised and expanded edition. Springer, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-540-66258-8 , pp. 10, 203 .

- ↑ Otto Forster : Analysis 1. Differential and integral calculus of a variable . 12th edition. Springer Spectrum, Wiesbaden 2016, ISBN 978-3-658-11544-9 , p. 150-151 .

- ↑ Jörg Arndt, Christoph Haenel: PI: Algorithmen, Computer, Arithmetik . 2nd, revised and expanded edition. Springer, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-540-66258-8 , pp. 11 .

- ^ Johann Heinrich Lambert: Contributions to the use of mathematics and their application. Verlag des Buchladen der Realschule, 1770, p. 156, limited preview in Google book search.

- ^ Peter Alfeld: pi to 10,000 digits. Department of Mathematics, University of Utah, August 16, 1996, accessed August 19, 2019 . List of the first 10 million positions on pibel.de (PDF; 6.6 MB).

- ↑ Shu-Ju Tu, Ephraim Fischbach: Pi seems a good random number generator - but not always the best. Purdue University, April 26, 2005, accessed August 19, 2019 .

- ↑ Jörg Arndt, Christoph Haenel: PI: Algorithmen, Computer, Arithmetik . 2nd, revised and expanded edition. Springer, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-540-66258-8 , pp. 194 .

- ↑ Jörg Arndt, Christoph Haenel: PI: Algorithmen, Computer, Arithmetik . 2nd, revised and expanded edition. Springer, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-540-66258-8 , pp. 33, 220 .

- ↑ Jörg Arndt, Christoph Haenel: PI: Algorithmen, Computer, Arithmetik . 2nd, revised and expanded edition. Springer, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-540-66258-8 , pp. 51-54 .

- ^ Karl Strubecker : Introduction to higher mathematics. Volume 1: Basics . R. Oldenbourg Verlag , Munich 1956, p. 87 .

- ↑ Delahaye : π the story. 1999, p. 211, limited preview in Google book search.

- ↑ Jörg Arndt, Christoph Haenel: Pi: Algorithmen, Computer, Arithmetik. Springer-Verlag, 1998, p. 117 f., Limited preview in the Google book search.

- ^ Wilbur R. Knorr: Archimedes and the Measurement of the Circle: A New Interpretation. Arch. Hist. Exact Sci. 15, 1976, pp. 115-140.

- ↑ Jörg Arndt, Christoph Haenel: PI: Algorithmen, Computer, Arithmetik . 2nd, revised and expanded edition. Springer, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-540-66258-8 , pp. 171 .

- ↑ Christoph J. Scriba, Peter Schreiber: 5000 years of geometry. 3. Edition. Springer, Berlin / Heidelberg 2009, ISBN 978-3-642-02361-3 , p. 172.

- ↑ De ruzies van van Ceulen - Biografieën - Ludolph van Ceulen (1504-1610). Van Ceulen's biography.

- ^ Richard P. Brent: Jonathan Borwein, Pi and the AGM. (PDF) Australian National University, Canberra and CARMA, University of Newcastle, 2017, accessed August 19, 2019 .

- ^ Stanley Rabinowitz, Stan Wagon: A Spigot Algorithm for the Digits of Pi. In: American Mathematical Monthly. Vol. 102, No. 3, 1995. pp. 195-203, (PDF; 250 kB). ( Memento from February 28, 2013 in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ Markus Steinborn: DerSalamin / Brent Algorithmus (AGM), seminar elaboration. (PDF) 3 elliptical integrals. Technische Universität Ilmenau, 2004, p. 5 , accessed on May 16, 2020 .

- ^ Eugene Salamin: Computation of Using Arithmetic-Geometric Mean , Mathematics of Computation, Vol 30 (135), 1976, pp 565-567.

- ↑ Ehrhard Behrends, Peter Gritzmann, Günter M. Ziegler: und Co., Kaleidoskop der Mathematik. Springer-Verlag, Berlin / Heidelberg 2008, ISBN 978-3-540-77888-2 , p. 157.

- ^ Rudolf Wolf: Handbook of astronomy, its history and literature. F. Schulthess, Zurich 1890, vol. 1, p. 128. ( digitized version )

- ↑ a b c Calculation of to 100,000 Decimals , Mathematics of Computation, Vol. 16, 1962, pp. 76-99, accessed on November 29, 2018 (English).

- ↑ Yasumasa Canada: Current published world record of pi calculation is as in the followings. In: Canada Laboratory home page. October 20, 2005, accessed May 1, 2010 .

- ↑ Fabrice Bellard: TachusPI. bellard, accessed on March 19, 2020 .

- ^ Fabrice Bellard: Computation of 2700 billion decimal digits of Pi using a desktop computer. bellard, February 11, 2010, accessed March 19, 2020 .

- ↑ New record: inventors and students calculate pi to five trillion digits. In: Spiegel Online . August 5, 2010, accessed January 5, 2015 .

- ↑ Alexander Jih-Hing Yee: 5 Trillion Digits of Pi - New World Record. numberworld, accessed on March 19, 2020 .

- ↑ Alexander J. Yee, Shigeru Kondo: Round 2… 10 Trillion Digits of Pi. On: numberworld.org. October 22, 2011.

- ↑ Alexander J. Yee, Shigeru Kondo: 12.1 Trillion Digits of Pi. On: numberworld.org. February 6, 2014.

- ↑ a b Pi. In: numberworld.org. March 15, 2019, accessed August 12, 2019 .

- ↑ Houkouonchi: 13.3 Trillion Digits of Pi. On: π -wissen.eu. October 8, 2014.

- ↑ Peter Trüb: The Swiss who calculated 22.4 trillion decimal places of pi. In: NZZ.ch. Retrieved March 21, 2017 .

- ↑ Home -> Success Stories - DECTRIS. In: dectris.com. Archived from the original on December 6, 2016 ; Retrieved December 6, 2016 .

- ↑ Alexander J. Yee: Records set by y-cruncher. In: numberworld.org. March 14, 2019, accessed on March 14, 2019 .

- ↑ Jens Minor: New world record: Google Cloud calculates the district number Pi to 31.4 trillion digits & makes it freely accessible. In: GoogleWatchBlog. March 14, 2019, accessed March 14, 2019 .

- ^ Timothy Mullican: Calculating Pi: My attempt at breaking the Pi World Record. In: Bits and Bytes | the ramblings of a sysadmin / cyber security professional. Timothy Mullican, June 26, 2019, accessed January 31, 2020 .

- ↑ Alexander Yee: Records set by y-cruncher. In: numberworld.org. January 30, 2020, accessed on January 31, 2020 .

- ↑ Alexander J. Yee: Pi. In: numberworld.org/. August 19, 2021, accessed August 20, 2021 .

- ^ Pi-Challenge - World record attempt by the University of Applied Sciences Graubünden - University of Applied Sciences Graubünden. In: University of Applied Sciences Graubünden - University of Applied Sciences Graubünden. University of Applied Sciences Graubünden, accessed on August 20, 2021 .

- ↑ Dieter Grillmayer: 2. The approximation construction of Kochanski ; In the realm of geometry: Part I: Ebene Geometrie, BoD - Books on Demand, 2009, p. 49 ( limited preview in Google book search), accessed on February 26, 2020

- ↑ a b c C. G. Specht: 40. Second approximation construction of the circle circumference . In: AL Crelle (ed.): Journal for pure and applied mathematics . tape 3 . G. Reimer, Berlin 1828, p. 405–406 ( digitized - digitized by SUB, Göttingen digitization center). Retrieved October 11, 2020.

- ↑ Hans-Wolfgang Henn: Elementary Geometry and Algebra. Verlag Vieweg + Teubner, 2003, pp. 45–48: The quadrature of the circle. ( Excerpt (Google) )

- ↑ Horst Hischer: Mathematics in school. History of Mathematics… (PDF) (2). Solution of classic problems. In: (5) Problems of Trisectrix . 1994, pp. 283-284 , accessed February 21, 2017 .

- ^ Claudi Alsina, Roger B. Nelsen: Charming Proofs: A Journey Into Elegant Mathematics . MAA 2010, ISBN 978-0-88385-348-1 , pp. 145-146 ( excerpt (Google) )

- ^ Construction of pi, swimming pool method. WIKIVERSITY, accessed February 19, 2017 .

- ^ Arnfried Kemnitz: Straight circular cylinder ; Mathematics at the beginning of your studies: basic knowledge for all technical, mathematical, scientific and economic courses, Springer-Verlag, 2010, p. 155 ff. ( Limited preview in Google book search), accessed on February 24, 2020.

- ^ Arnfried Kemnitz: Parallelepiped and Cube ; Mathematics at the beginning of your studies: Basic knowledge for all technical, mathematical, scientific and economic courses, Springer-Verlag, 2010, pp. 153–154 ( limited preview in Google book search), accessed on February 24, 2020.

- ^ Weierstrass definition of . In: Guido Walz (Ed.): Lexicon of Mathematics . 1st edition. Spectrum Academic Publishing House, Mannheim / Heidelberg 2000, ISBN 3-8274-0439-8 .

- ↑ E. Freitag: Theory of Functions 1. Springer Verlag, ISBN 3-540-31764-3 , p. 87.

- ↑ Heinrich Behnke, Friedrich Sommer: Theory of the analytical functions of a complex variable (= The basic teachings of the mathematical sciences in individual representations . Volume 77 ). Springer-Verlag, Berlin / Heidelberg / New York 1965, p. 120 ff .

- ↑ Heinrich Behnke, Friedrich Sommer: Theory of the analytical functions of a complex variable (= The basic teachings of the mathematical sciences in individual representations . Volume 77 ). Springer-Verlag, Berlin / Heidelberg / New York 1965, p. 245-246 .

- ↑ Konrad Knopp : Theory and Application of the Infinite Series (= The Basic Teachings of Mathematical Sciences . Volume 2 ). 5th, corrected edition. Springer Verlag, Berlin (inter alia) 1964, ISBN 3-540-03138-3 , p. 212-213 .

- ↑ Konrad Knopp: Function Theory II . Applications and continuation of the general theory (= Göschen Collection . Volume 703 ). 11th edition. de Gruyter , Berlin 1965, p. 41-43 .

- ↑ Herbert Meschkowski : Infinite rows . 2nd, improved and enlarged edition. BI Wissenschaftsverlag , Mannheim (among others) 1982, ISBN 3-411-01613-2 , p. 150 ff .

- ↑ Klaus Jänich : Introduction to Function Theory . 2nd Edition. Springer-Verlag, Berlin (inter alia) 1980, ISBN 3-540-10032-6 , pp. 140 .

- ↑ Leonhard Euler: Introduction to the Analysis of the Infinite . Springer Verlag, Berlin / Heidelberg / New York 1983, ISBN 3-540-12218-4 , pp. 230 ff . (First part of the Introductio in Analysin Infinitorum - reprint of the Berlin edition 1885).

- ↑ Konrad Knopp : Theory and Application of the Infinite Series (= The Basic Teachings of Mathematical Sciences . Volume 2 ). 5th, corrected edition. Springer Verlag, Berlin (inter alia) 1964, ISBN 3-540-03138-3 , p. 397-398, 454 .

- ↑ Eberhard Freitag, Rolf Busam: Function theory 1 (= Springer textbook ). 3rd, revised and expanded edition. Springer Verlag, Berlin (inter alia) 2000, ISBN 3-540-67641-4 , p. 200-201 .

- ↑ Konrad Knopp : Theory and Application of the Infinite Series (= The Basic Teachings of Mathematical Sciences . Volume 2 ). 5th, corrected edition. Springer Verlag, Berlin (inter alia) 1964, ISBN 3-540-03138-3 , p. 454 .

- ↑ Petr Beckmann: History of Pi . St. Martin's Press, 1974 ISBN 978-0-88029-418-8 , pp. 174-177 (English).

- ↑ tug.ctan.org

- ↑ Road Map. Retrieved June 27, 2020 .

- ↑ Bob Palais: π is wrong! In: The Mathematical Intelligencer. Volume 23, No. 3, 2001, Springer-Verlag, New York, pp. 7-8. math.utah.edu (PDF; 144 kB).

- ↑ Ulrich Pontes: Revolution against the circle number: physicist wants to abolish Pi. In: Spiegel online. June 28, 2011. Retrieved June 29, 2011 .

- ↑ Tauday / The Tau Manifesto , accessed on April 16, 2011. Bob Palais himself initially suggested a double π, see the homepage of Bob Palais at the University of Utah , accessed on April 15, 2011.

![{\ displaystyle [3]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f671027d56f9c24d65c03a4a26eb0d3b933f4f15)

![{\ displaystyle [3; 7]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b143dda8c65c1ca85c41576c4c8a3d8f5df6407e)

![{\ displaystyle [3; 7.15]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a5de106dfde7219a2e61f44226a648013e756f01)

![{\ displaystyle [3; 7,15,1]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d6690573890eb8baceba1aa850998652677db2ad)

![{\ displaystyle [3; 7,15,1,292]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/035629dce1f7b9ef6e2272ca0d981681f81fcf06)

![{\ displaystyle [3; 7,15,1,292,1]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/8cd5fc7190b3224146b644aa8954508d7af79efa)

![{\ displaystyle [3; 7,15,1,292,1,1,1,2,1,3]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/099eebe5d3e89f248a4775a63396dfef1a4a4cf0)

![{\ displaystyle [3; 7,15,1,292,1,1,1,2,1,3,1,14,2,1,1,2,2,2,2,1]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/cda68b82adda1e0c90529a1f264b39e140702bd2)

![\ frac {22} {7} = [3; 7], \ quad \ frac {355} {113} = [3; 7,15,1]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/966dabb64e9213b2499d4b4361961c7a39269dd4)

![{\ displaystyle 1 \, \ mathrm {[LE]}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/0a9b31d2257a31e08c9c358342bf994ea1c43bc5)

![{\ displaystyle \ pi \, \ mathrm {[LE]}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f5b7f9ca109f85edea8123b81106ffd39e5fd926)

![{\ displaystyle V_ {Z} = r ^ {2} \ pi h_ {Z} = 1 ^ {3} \ cdot \ pi = 3 {,} 14159 \ dotso \, \ mathrm {[VE]}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/39176c952430c23c28dcda92982feac8ad84a24f)

![{\ displaystyle h_ {Q} = {\ frac {1 ^ {3} \ pi} {1 ^ {2}}} = \ pi = 3 {,} 14159 \ dotso \, \ mathrm {[LE]}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/39e7a5614054644522052ea7c6ff76f03fbb42d3)

![{\ displaystyle 1 \; \ mathrm {[LE]}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/86400bfc9081bdb72bf23c7a26a04279727ae97d)