The 1001: A Nature Trust

At The 1001: A Nature Trust , the members concerned in accordance with 1001 as Club (of) 1001 is known, it is a foundation that works for financial support of the World Wildlife Fund (WWF; later: World Wide Fund for Nature ) established has been. It was brought into being at the beginning of the 1970s with the support of the South African entrepreneur Anton Rupert and the then President of WWF International , Bernhard zur Lippe-Biesterfeld .

founding

According to the WWF, the then and first President of WWF International , Prince Bernhard of the Netherlands , started an initiative in 1970 that was intended to provide the WWF with a reliable financial basis. The WWF set up a $ 10 million asset pool known as The 1001: A Nature Trust. Prince Bernhard acted as raison d'Être of the Club of 1001 and was at the center of an extensive system of orders that the WWF had introduced in the years before Prince Bernhard's resignation, based on the model of modern monarchies, in order to promote the formation and loyalty of the elite .

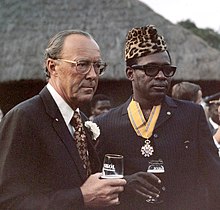

The original idea for setting up the club seems to have come from WWF founding member Anton Rupert and, according to the WWF, was "made concrete" by Prince Bernhard. Rupert's knowledge of marketing as well as his and Prince Bernhard's complex and global business networks flowed into the club. Prince Bernhard was particularly well known for his extensive contacts in business and with people in power around the world. He was a lifelong participant, president and promoter of several important business networks, including the Bilderberg Group (since 1954) and the lesser known Mars and Mercury Group (founded in 1926). The establishment of the capital fund, with the interest of which the WWF was able to cover its administrative fixed costs and to assure potential donors that "100 percent of the money donated to the international secretariat for nature conservation will actually be spent on nature conservation projects", was recognized as the "greatest legacy" (Alexis Schwarzenbach) Ruperts.

prehistory

The WWF was founded to provide funding, but in contrast to its initial successes initially only had limited success. WWF co-founder Peter Scott had assumed that he could raise the necessary sums and had expected a sum of 25 million US dollars from "the rich". But only after years, in 1968, did the total amount of donations received by the WWF reach one million British pounds . This sum was seen as too small for the wide range of tasks facing the WWF. The WWF had set itself the goal of being able to spend 2.3 million British pounds annually. In 1968, Prince Bernhard wrote in the WWF yearbook that new sources of money would have to be tapped to achieve this goal. At this point in time the WWF had already been able to establish contacts with “the rich”, but did not receive the hoped-for sums from them. On the one hand, the WWF believed that unconditional funding should be sought, but on the other hand it was much easier to get specific donations for specific projects than money to cover the administrative costs of an organization. In 1971 the finances of the WWF were put on a new basis with the establishment of the exclusive club The 1001: A Nature Trust . Prince Bernhard approached 1,000 wealthy people with the request to donate 10,000 US dollars each to the WWF.

procedure

The establishment of a capital fund had already been proposed by the banker and WWF board member Samuel Schweizer in 1964, but until Rupert joined the WWF had only done extensive research into how to obtain tax exemption in various countries and had also come up with a plan taken up by Max Nicholson from 1961, who provided for the establishment of an exclusive club for very wealthy WWF sponsors. When the WWF was looking for a way to raise the $ 10 million fortune, Anton Rupert proposed to WWF President Prince Bernhard that one thousand people should each contribute $ 10,000 .

Rupert had this plan, funding for a capital fund to collect in the amount of ten million US dollars, to know when he in 1970 Chairman of the newly established in January Fundraising was -Ausschusses. He spoke to an employee and manager of his company Rothmans International , the economist and lawyer Charles de Haes , who had built and managed cigarette factories for Rupert in Sudan and Kenya . Rupert and de Haes decided to ask 1,000 people for a donation of $ 10,000 each. De Haes was to receive unlimited power of attorney for the implementation for two years and would continue to receive his salary from Rupert during this time. After Rupert and de Haes presented their plan to Peter Scott and Fritz Vollmar at a meeting in Slimbridge , the center of Scott's commitment to protecting wild birds in Gloucestershire , Rupert and de Haes decided to send a personal invitation from Prince Bernhard to 1,000 donors to found the Club 1001 together with him . Rupert and de Haes visited Prince Bernhard in the Netherlands and presented him with the invitations made on letter paper from Rothmans' London headquarters , for which the cigarette box designer Rothmans had designed the club logo - a globe and the gold-embossed numbers 1001. Prince Bernhard accepted the logo and made Charles de Haes his "honorary personal assistant" who was supposed to set up Club 1000.

Together, Rupert and Prince Bernhard developed the concept of the Club of 1001 in 1970 , which was intended to help the WWF cover its operating costs. In November 1970, the WWF Board of Trustees approved the plan, which was fully implemented by the end of 1973. For the one-time donation, the 1,000 wealthy people received lifelong membership in the club while their names were kept secret by the WWF. The members - individuals or corporations - were given access to exclusive celebrations and dinners for the substantial donation, where they could come into contact with other wealthy and noble people. Companies were also able to pay the US $ 10,000 on behalf of selected representatives, but membership in the club was only granted to individuals. In the club's brochures, the members only appeared in the form of lists of names, stating the country in which they were domiciled. From London Traditions jeweler Garrard produced club-1001 Buttons acted as "effective means to put hesitant board members at meetings under peer pressure" (Alexis Schwarzenbach) and de Haes subsequently developed a " Ponzi scheme " by every new member to address asked from potential donors, whom he then went to. The external presentation of Club 1001 made use of the symbolism of an elegant golf or country club . Club members gathered at receptions held at Prince Bernhard's palace in the Netherlands. The WWF organized international and national meetings for members as well as special trips to WWF projects around the world. Occasionally there were social gatherings for the benefit of the members in cities such as Los Angeles , London, or Geneva, which were usually hosted by a resident member. Exclusive vacation trips could also be booked, the first of which was an East Africa safari in 1974 with the participation of 20 paying members. In order not to endanger the tax exemption, the membership fees did not include any benefits such as the use of a club house or free entry to WWF-sponsored wildlife reserves.

Anton Rupert and Prince Bernhard worked closely together to promote and market nature and species protection. Both developed their networks, from which the Club of 1001 of the WWF should be recruited. Rupert, himself a close and lifelong friend of Prince Bernhard, was widely regarded as the leading African businessman in South Africa and was the founder and chairman of Rembrandt tobacco company , head of Rothmans International and one of the wealthiest men in South Africa. Earlier in his career, Rupert was closely associated for many years with the Afrikaner Broederbond , the nationalist secret society of Africans that had a strong influence on governments during the apartheid era. At the suggestion of Prince Bernhard in 1968 to found a national branch of the WWF in South Africa, Rupert set up the Southern African Nature Foundation (SANF) as the South African branch of the WWF , of which he himself became president, and won South African business people for its board of trustees to join. In addition, Rupert acted as curator of WWF International for a period of 22 years until 1990, although a clause in the original charter of the WWF provided for a limit of two three-year terms for members. Rupert gained such influence within WWF circles that he was able to provide the general director for the international headquarters of WWF in Switzerland .

During Prince Bernhard's presidency for WWF International , in 1971 or shortly before, Rupert proposed that Prince Bernhard should be assigned a personal assistant to work in the main office of WWF International while his salary was still on his Parent company should be paid. Rupert de Haes suggested this use. In 1971, de Haes, made available free of charge by Rupert, was hired to work alongside Prince Bernhard to set up a permanent foundation for WWF and achieve the operational goal of $ 10 million by soliciting the donations. De Haes, who during the founding phase of the Club of 1001 paid a visit to all WWF country sections (originally "National Appeals", from 1977 "National Organizations" or "NOs" for short), carried out his assignment from 1971 to 1973 in this way successful from the fact that he was appointed co-director general of WWF-International alongside Fritz Vollmar in 1975 and then sole director general in 1977 or 1978, a position he held until 1993. In November 1973, de Haes had achieved the target of 1,000 donors, 60 of whom came from Germany.

By the 1990s, the 1,000 donors' contributions had already been increased to $ 25,000 each.

Goals and meaning

Until the late 1960s, the WWF had a relatively modest donation volume. It was not until the 1970s - that is, at the same time as Prince Bernhard founded The 1001: A Nature Trust - that a substantial increase in donations could be achieved. According to the WWF, WWF International has been able to meet its basic administrative costs with the help of the foundation since the foundation of "The 1001". Most of WWF's administrative expenses were now covered by interest income from this and other foundations.

The establishment of a permanent foundation for WWF International aimed to enable the WWF's international headquarters to be financially independent from the national sections. The administration of the organization was to be financed with the new capital stock, so that the receipt of donations could be used in full for nature conservation work. In this way, the assets raised by the Club of 1001 should allow the international WWF headquarters to assure potential donors that their money will not be used for the administrative costs of the headquarters, as these were already largely secured by the foundation's assets. The WWF was therefore able to advertise that every donation is used directly for nature conservation projects. Nevertheless, even in the 1970s, the WWF did not have any greater financial leeway. The expenditure was strictly based on the amount of donation, while there was no room for reserves. One of the consequences of the agreement of The 1001 , however, was that WWF International became financially independent from the national WWF sections existing worldwide.

The WWF itself also states that the foundation aims to "engage influential members of society for the protective activities of WWF, those who are able to bring about a change in the world".

The increased focus on fundraising led to rivalries among environmental organizations. For example, after the establishment of the African Wildlife Foundation (AWF), WWF circles perceived a threat to WWF from rapidly growing competition for the wildlife fund market. Increasingly, organizations began to target the general public for funding, particularly in Europe and the United States, where wealth rose. The audience was overwhelmed with terrible news about nature conservation and species protection and the threats posed by people. Images of the cruelty of poachers became widespread and a sense of urgency was created. The strong message against hunting and resource consumption became an efficient means of raising funds. From the 1970s onwards, general public donations began to outweigh contributions from elitist organization members. However, the messages addressed to the general public did not always convey the more nuanced attitudes of the organization's staff and its wealthy donors to hunting and resource consumption. This sometimes led to conflicting strategies and sudden U-turns by environmental organizations, such as the ban on the ivory trade in the 1980s.

The solid image of WWF International, which also corresponded to the exclusive, upper-class membership of Club 1001, was in stark contrast to the self-image of some national WWF organizations such as Italy, the Netherlands and Switzerland, which began in the 1970s, to be ecologically active become.

composition

The WWF treats the club member lists with strict confidentiality. Although the membership lists were confidential, they were printed annually and distributed among the members. Some of them can therefore be viewed in the estates of deceased members such as Peter Scott or are circulated on the Internet in the form of scans, for example on the Scribd web portal .

New donors can only join the exclusive club if a corresponding number of members leaves.

Information on members from the 1970s and 1980s

In a series of detailed and apparently well-informed articles in the British magazine Private Eye in 1980 and 1981, details of some members were published anonymously. Though the magazine is known for publishing numerous erroneous articles, a copy of the Club of 1001 membership list for 1987, owned by historian Stephen Ellis , confirmed many of the claims made. Member names that have "leaked over the years include Baron von Thyssen, Fiat boss Gianni Agnelli and Henry Ford, as well as corrupt politicians like Mobutu Sese Seko of Zaire, former President of the International Olympic Committee Juan Samaranch, and beer baron Alfred Heineken" ( The Guardian ). Also known was the membership of Bernhard Grzimek , who, despite his function as a figurehead and embodiment of the "romantic soul" (Wilfried Huismann) of the WWF , is said to have formed an exception among the businessmen-dominated members of the 1001 Club .

Many members were people from the banking sector , from other business sectors, from the secret service , from the military as well as heads of state and thus the global elite networks that participated in the Bilderberg conferences . In addition, several members were among the 1,001 clubs to the South African business sector, which is the subject of a UN - boycott during apartheid -Regimes was. Therefore, there were both special connections between (parts of) the global Bilderberg elite networks and animal species protection over the presidency of Prince Bernhard for WWF International , as well as express connections between WWF International and South Africa in the field of environmental philanthropy . The various lists in circulation for 1978 and 1987 included names of a number of famous businessmen and bankers such as David Rockefeller, Henry Ford II, several members of the De Rothschild family and the Agnelli family. At the time when the South African economy was still officially boycotted against the global economy, members of the Club of 1001 included South African business people such as Anton Rupert and his son Johann Rupert (head of the Rembrandt / Richemont Group), Freddie de Guingand (founder the business lobbyist organization South Africa Foundation ), Louis Luyt (known as the “Fertilizer King” of South Africa) or Rupert's important business rival Harry F. Oppenheimer (owner of Anglo American and De Beers ). Some of the well-known names that are on the circulating lists of the Club of 1001 also appear on the officially published membership list of the 21-Club , also founded by Anton Rupert and Prince Bernhard , a club of corporations and wealthy business people with a Membership fee of 1 million euros each supported Rupert's operations. In his book WWF - The Biography 2011, the historian Alexis Schwarzenbach cited as a digital source a list of members of the Club of 1001 he viewed in 2010 , which had been published on the web portal.

Prince Bernhard himself was a member of the 1001 Club with the number 1001.

When asked how the business networks, in which Prince Bernhard was involved, helped to find suitable candidates for the club during his WWF years, no information was provided by the WWF, which refuses to provide information about the club members. Two lists also published on the Internet - one for 1978 and one for 1987 - suggest, however, that there was a "mutual fertilization" (Spierenburg and Wels) between the various networks of Prince Bernhard. These two lists were tracked down by British journalist Kevin Dowling , who, with WWF support, had made a documentary about ivory poaching, but later fell out with WWF over the issue of Operation Lock . The German journalist Wilfried Huismann also claims that through research he came into possession of the two editions of the membership lists of the Club of 1001 for 1978 and 1987, which can now also be found on the Internet. According to Huismann, these two available editions come from the estate of Kevin Dowling, who also made a never-aired documentary about WWF's activities in Africa. Many members of these lists are celebrities of the political and financial world elite. Accordingly, among them are:

Selection of members of "The 1001" according to the confidential membership lists from 1978 and 1987 from the estate of Kevin Dowling Surname Remarks Origin or residence Agha Hasan Abedi President of BCCI Bank Pakistan Karim Aga Khan IV. (Prince Aga Khan IV.) Billionaire and Muslim spiritual leader Pakistan, United Kingdom, ... Giovanni Agnelli Fiat boss Italy Baron Astor of Hever President of the Times United Kingdom Stephen Bechtel Bechtel Group United States Berthold Beitz Croup Germany Martine Cartier-Bresson France Charles de Chambrun Leading Member of the Front National France Joseph Cullman III CEO Philip Morris United States Sir Eric Drake British Petroleum General Manager United Kingdom Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh from 1961 President of WWF-UK, 1981–1996 President of WWF International United Kingdom Friedrich Karl Flick Industrialist and billionaire Germany, Austria Henry ford ii United States Manuel Fraga Iribarne Minister in Franquism , founder of the right-wing Alianza Popular Spain C. Gerald Goldsmith United States Ferdinand HM Grapperhaus Dutch Minister of Finance Netherlands Alfred Heineken known as the "beer king" Netherlands Lukas Hoffmann Hoffmann-La Roche Switzerland Lord John King British Airways United Kingdom Sheikh Salim Bin Ladin older brother of Osama bin Laden Saudi Arabia John H. Loudon CEO Shell , President of WWF International from 1976 to 1981 Netherlands Daniel K. Ludwig Shipowner and billionaire United States José Martínez de Hoz Oligarch, Minister of Economy during the military dictatorship of Jorge Rafael Videla Argentina Robert McNamara US Secretary of Defense of the Vietnam era United States Keshub Mahindra Mahindra Group India Mobutu Sese Seko Zaire's long-term dictator Zaire Mærsk Mc-Kinney Møller Major shipowners Denmark Prince Bernhard of the Netherlands 1962–1976 President of WWF International , then remained deeply involved in WWF and its activities Netherlands Queen Juliana of the Netherlands Wife of Prince Bernhard Netherlands Harry Frederick Oppenheimer Anglo American Corporation South Africa David Rockefeller Chase Manhattan Bank United States Tibor Rosenbaum BCI , Geneva Switzerland Baron Edmond von Rothschild France Juan Antonio Samaranch IOC President Spain Peter from Siemens Siemens Germany Hans Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza Switzerland Joachim Zahn Daimler Benz Germany

According to Huismann's research, at least during this period there were also many personalities from the German business elite, such as Berthold Beitz , Otto Boehringer , Franz Burda , Friedrich Karl Flick , Hans Gerling , Otto Henkell , Alfred Herrhausen , Kurt A. Koerber , Willy Korf , Hans Merkle , Rudolf-August Oetker , Heinz Pferdmenges , Peter von Siemens , Axel Springer , Prince Johannes von Thurn and Taxis , Alfred C. Toepfer , Otto Wolff von Amerongen and Joachim Zahn .

The historian Alexis Schwarzenbach , author of the book WWF - Die Biographie , states that, according to an old list of members of the Club of 1001, many Swiss members from Basel (where, thanks to Luc Hoffmann, Charles de Haes was able to get many wealthy people or companies to join the WWF To support capital funds) or Geneva (where the WWF was based) and the respective surroundings, while in the Zurich area, which is more influenced by economic freedom, it is said to have been difficult to raise money for environmental protection as early as the early 1970s. According to Schwarzenbach, the members of the Club of 1001 came from over 50 countries. In 1978 the five most frequently represented countries of origin were the USA with 177 members, Great Britain with 157, the Netherlands with 107, South Africa with 65 and Switzerland with 62.

Current members

According to a recent report by WWF (as of 2014), the anonymous members of The 1001: A Nature Trust are a “respected group of people” made up of “philanthropists from over 50 countries”. According to WWF, among them are “owners and administrators of large companies, entrepreneurs, scientists and artists” who, regardless of “their political, personal and business interests” - according to WWF - “all share the same passion for the environment - and first and foremost the same need to support the world's leading protection organization ”. In addition to individuals, according to the WWF, “whole families” come together in the club.

criticism

The special relationship of the WWF to the economy fueled the criticism that the WWF shows bias in favor of its donors. This criticism was first raised within the WWF leadership when the British satirical magazine Private Eye published an article entitled "Lowlife Fund" in August 1980. Like most of the articles in the journal, which specialized in attacks against the establishment, the 1980 article was anonymous and contained well-researched, albeit polemical, facts. The article stated that some WWF supporters and officials feared that they would lose their share of the public donations because “militants” like Friends of the Earth and Greenpeace “took the initiative in nature conservation”. The cooperative WWF dealings with industry, which differed significantly from the confrontational course of the more left-wing, competing environmental organizations, goes back to the alleged decline in willingness to donate. The support of the WWF by Club 1001 was seen as the reason for this strategy. With reference to a highly confidential list of members from 1978, Private Eye made it known that in addition to prominent business people who worked in environmentally sensitive industries such as the oil, chemical or mining industries, Club 1001 also included people who had gone bankrupt Crimes were accused or whose vitae showed other "anomalies" that were hardly compatible with the goals of the foundation. For example, the US billionaire Daniel K. Ludwig, who had made part of his fortune making oil tankers, was accused of “destroying a large piece of the Brazilian rainforest,” and Zaire's President Mobutu was accused of “one of the the largest massacre of elephants in Africa ”. WWF International initially decided not to “react” to the article and the top decision-making body of the WWF shelved the topic about considering the environmental responsibility of companies in donations two years later with a final stance: “It was noted that no church has ever refused donations from sinners. On the other hand, there was a risk that companies would try to buy into seriousness without changing their irresponsible behavior. "

In his book At the Hand of Man: Peril and Hope for Africa's Wildlife , Raymond Bonner criticized WWF from various angles in 1993 and also cited the accusation of neo-colonialist methods. In view of the strict confidentiality of membership in the Club of 1001 , Bonner suspected that the WWF intended to conceal some club members with dubious reputations. According to Bonner, the disproportionate number of white South Africans offered many of them during the apartheid period one of the few opportunities to become members of an international club and to establish contacts with industrialists and nobles. In Bonner's opinion, the strong influence of South Africans was one of the reasons why the WWF had long supported South Africa's resistance to a ban on the ivory trade . Ann O'Hanlon of Washington Monthly , who called Bonner's allegations a “careful indictment by the WWF,” wrote in her review of his book: “The secret list of members includes a disproportionate percentage of South Africans who are all overjoyed in an era of social exile to be welcomed into a society of social elite. Other contributors include business people with suspicious connections, including organized crime, the development of environmental degradation, and corrupt African politicians. Even an internal report called the WWF's approach self-centered and neocolonialist. (The report was largely covered up.) "

Confidential elite network as a focal point for controversial connections

According to Stephen Ellis , most of the known members of the 1001 Club were "people of impeccable integrity, although it should be noted that the 1001 club members included a small number of people of ill repute such as President Mobutu Sese Seko of Zaire and Agha Hasan Abedi, former President of the Bank of Credit and Commerce International (BCCI), responsible for the world's largest financial fraud in history. “Both Mobutu Sese Seko and Agha Hasan Abedi were known members of the 1001 Club for at least 1987 . According to Bonner, WWF could possibly have an interest in maintaining the confidentiality of membership have as corrupt force President Mobutu of Zaire, as well as at the American industrialist Daniel K. Ludwig , whose company Amazonas - rainforests were cut down.

Stephen Ellis and Gerrie ter Haar (2004) described the WWF Club of 1001 "as an association in which European royalty come together with leading industrialists, but also with some clearly dubious figures of government corruption and secret services in the world" . According to the authors, the ostensibly non-political body WWF created access to a type of elite network that enabled the elite membership of international networks and societies to enable African leaders to connect global elites while maintaining a kind of secrecy, which they liked, as evidenced by President Mobutu's membership in the Club of 1001 . In this context, Ellis and ter Haar regard it as one of the most important incentives for secret societies that “membership offers opportunities to conduct political business unobserved by the masses of the population and to forge bonds of solidarity that go far beyond the normal range”, whereby “the Confidentiality that welds people together ”.

Influence of South African elites and platform for evading sanctions

Ellis, who endeavored to show the influence of the lobby of white South Africa on the funding of WWF International , also emphasized that "the identities of the 1001 members of the Club of 1001 very closely reflect Bernhard's own circle of friends". According to Ellis, they also revealed "the influence of leading South African personalities". The available membership list for 1987 included at least 60 South Africans, including many and prominent members of the politically extremely influential African Broederbond , who were at the helm of companies that were dependent on the Broederbond's patronage , such as Johannes Hurter (Chairman of Bank Volkskas ), Etienne Rousseau ( Chairman of the Federale mining and industrial group ) and Pepler Scholtz (former manager of the Sanlam financial group ).

In particular, the 1001 Club was popular with South African business managers during the apartheid regime, who it allowed to network and do international business while circumventing international sanctions. Spierenburg and Wels (2010) also emphasize that the Club der 1001, with its receptions in Prince Bernhard's palace in the Netherlands, offered South African business people a platform to meet their international colleagues even during the boycott against South Africa. A number of Dutch businessmen on the membership lists who were connected to each other via Prince Bernhard were at times accused of breaching sanctions.

At least three South African members of the Club of 1001 were implicated in the so-called Muldergate affair in South Africa, which revealed that the Pretoria government had used funds from intelligence agencies to buy control of daily newspapers. One of them, Louis Luyt , who played a significant role in the affair, was a former business partner of Anton Rupert.

There was both a cooperation between Rupert and WWF as well as intensive cooperation and intervention by WWF International in South African nature conservation policy and, in connection with this, a connection between WWF and apartheid policy. Spierenburg and Wels see the position of Charles de Haes as an important problem, who was entrusted with the realization of the Club of 1001 project as Prince Bernhard's personal assistant from 1971 to 1977 before his appointment as General Director of the WWF . De Haes was born in Belgium and marked Belgium as the country of origin on WWF public lists, but he grew up in South Africa. De Haes, who had been hung up in Rupert's Rembrandt Group before his assistantship to Prince Bernhard, received letters of introduction from Prince Bernhard with royal letterhead as Prince Bernhard's assistant and was able to use Prince Bernhard's networks to attract 1,000 donors within three years for the club of 1001 . But the South African entrepreneur Rupert continued to pay de Haes' salary, even when he was appointed co-director of WWF in 1975 and sole director general in 1977 and thus officially worked for the WWF and, according to Bonner, at the same time for a South African company. With the help of royal support, first Prince Bernhard and later Prince Philip , de Haes was able to hold onto the position of General Director until 1993/1994. Bonner criticized the lack of transparency and accountability of the WWF under de Haes with the words:

“It is unlikely that any other charitable organization that depends on public support operates with such little accountability and in such secrecy as WWF has under de Haes. It is easier to penetrate the CIA. "

“It is unlikely that any other nonprofit dependent on public support would operate with as little accountability and in such obscurity as WWF did under de Haes. It is easier to penetrate the secrets of the CIA than those of the WWF. "

Operation lock

At the time of the leadership of WWF International by de Haes there was also a joint approach in Operation Lock , which is seen as further evidence of the close mutual connection at least between WWF International and thus Prince Bernhard's with South Africa. The joint operation was initiated by Prince Bernhard, who remained closely connected to the organization even after his presidency of WWF International , and allegedly took place without Prince Philip's knowledge. The undercover measure called Operation Lock was promoted and supported by the then head of the Africa program of WWF International , John Hanks, and was deployed in 1987 in South Africa by KAS Enterprises .

The private security company KAS Enterprises, based in London, belonged to the famous founder of the British elite commandos Special Air Service (SAS), David Stirling . The mercenaries employed by the KAS were former British SAS commandos . In the second half of the 1980s, as part of an agreement with WWF representatives, they trained anti-poaching units in Namibia, then still under control of South Africa, and in Mozambique , where the South African apartheid government was pursuing a policy of destabilization .

In addition, KAS carried out the covert operation (code name Operation Lock or Project Lock ) in South Africa, with ivory and rhinoceros horn dealers being caught and the trade being ended. The operation was infiltrated by South African intelligence officials. The head of the anti-poaching team, Ian Crooke, offered to help the South African secret service fight the anti-apartheid movement in exchange for help in the fight against poaching and the trade in wildlife products. Operation Lock mercenaries became involved in anti- ANC activities, which were part of the general strategy of the apartheid system. Poaching and anti-poaching measures were central components of South Africa's destabilization policy towards neighboring countries. The WWF, with which Prince Bernhard and Anton Rupert were closely connected, was involved in these processes through Operation Lock . In 2011, Schwarzenbach published results from the Sofaer Chronology , which arose after Prince Philipp commissioned the US attorney Abraham Sofaer to go through the available documents and to compile a chronology of the events for the assessment of the question of guilt. The Sofaer chronology According to Hanks and Crooke met in November 1987 in London, "to discuss whether the KAS Enterprises dealer organizations that made with ivory and rhinoceros horn shops, could subvert (" Operation Lock ")" and agreed “That nobody within the WWF should find out about the project”. According to the internal WWF report, Hanks and Prince Bernhard agreed that the KAS project would be financed by Prince Bernhard, "provided that the WWF was not involved in the action."

Some of the anti-poaching activities of the KAS, and thus various aspects of Operation Lock , were disclosed in July 1989 by Reuters correspondent Robert Powell and later by Stephen Ellis. Powell hadn't been able to connect to WWF yet. The WWF then remained covert and continued to work with KAS. Triggered by Powell's article, however, the journalist and editor of Africa Confidential , Stephen Ellis, investigated the matter further and published some results in The Independent in 1991 , while the WWF denied that de Haes was aware of the WWF's involvement. When asked why the WWF South Africa, from where part of the ivory and rhinoceros horn smuggling to protect the apartheid regime was financed through the SADF and whose ports served as a hub for the handling of the smuggling, never as a target of the international WWF campaign against the rhinoceros horn trade was included, the WWF only replied that the item had "never emerged".

According to Stephen Ellis, however, the WWF had transferred money to Prince Bernhard in a secret transaction, which he used to pay for the command unit of the security company KAS. As a result, the money, before it was sent to Prince Bernhard for Operation Lock by the WWF via unusual transactions , had come in the opposite direction through Prince Bernhard's mediation to WWF-International. In December 1988, the auction house had Sotheby's two paintings (by Bartolome Esteban Murillo and Elisabetta Sirani ) from the possession of Prince Bernhard auctioned together 610,000 British pounds earned was donated to which the proceeds instructed Prince Bernhard of WWF International. However, the money was not used for the nature conservation work of the WWF, but within a few weeks after the sale, Prince Bernhard asked the asset management of the Club of 1001 to transfer 500,000 British pounds from the account of the Club of 1001 to the Dutch account of his wife, Queen Juliana . According to WWF internal documents, the amount of 500,000 British pounds was required for Operation Lock , according to the managing director of the South African WWF branch, Frans Stroebel , while de Haes consented to the requested use of the money and the WWF kept the remaining amount of 110,000 British pounds could.

When the operation was revealed, the embarrassed WWF responded by trying to divert Prince Bernhard's attention by placing all responsibility on Charles de Haes' then head of WWF International's South Africa program , John Hanks, who ran the project without consent the WWF representative initiated. John Hanks himself remained active in nature conservation and in 1997, at his request, helped Anton Rupert to set up the PPF , whose CEO John Hanks remained until 2000. The PPF was the most important lobbying organization for cross-border environmental protection in southern Africa and was not only under the patronage of Prince Bernhard, but also under that of Nelson Mandela , although an investigation commissioned by Mandela in 1994 or 1995 under the leadership of Judge Mark Kumleben into the WWF's activities in South Africa during the apartheid years had concluded that there was an extensive and intertwined network of espionage and business interests that nature conservation might have only served as a cover. Ramutsindela et al. concluded that nature conservation activities and support in the South Africa region should not be viewed in isolation from anti-communist campaigns, but formed part of these campaigns, especially when the line between “poaching” and “terrorism” was blurred for ideological reasons. The networks that emerged during the Cold War era showed the influence of elites remaining outside the state's borders on the development of South African regions.

conspiracy theories

The Club of 1001 - like the Bilderberg Conferences - has given rise to various conspiracy theories in books and internet forums, possibly encouraged by the lack of publicly available membership lists and information about their meetings.

Ramutsindela et al. (2011) emphasize in this context that "one of the greatest dangers in writing about the type of elite networks and initiatives is that readers can accuse the authors of creating, participating in or contributing to conspiracy theories".

literature

- Raymond Bonner: At the Hand of Man: Peril and Hope for Africa's Wildlife . Knopf, New York 1993, ISBN 0-679-40008-7

Web links

Footnotes

Remarks

- ↑ a b While Bonner stated that de Haes also received his salary from Rupert during his time as WWF General Director, this was denied by the WWF. (Source: Günter Murr, Development and options for action by environmental associations in international politics: the example of WWF , series of publications on political ecology, Vol. 1, Ökom-Verl., Munich 1996, p. 51, footnote 213; with reference to Bonner 1993, P. 70.) According to Schwarzenbach, from 1975 his salary was no longer paid by Anton Rupert, for whose company he no longer worked, but by a group of sponsors, to which Luc Hoffmann belonged. (Source: Alexis Schwarzenbach, WWF: Die Biographie , Collection Rolf Heyne, 1st edition, Munich 2011, p. 155, footnote 55 / p. 332)

- ↑ Raymond Bonner stated that he himself was in possession of lists of members of the Club of 1001 for the years 1987 and 1989 and referred to the issues of Private Eye of August 1, August 15 and September 27, 1980, in which the names of some members may be mentioned. (Source: Raymond Bonner, At the hand of man: peril and hope for Africa's wildlife , Alfred A. Knopf, 1st edition, New York 1993, footnote to p. 68 / p. 295)

- ↑ For examples of conspiracy interpretations relating to the Club of 1001 , see Ramutsindela et al. on J. Beame (2010, De macht achter de macht: de 1001 Club, eugenetica en duistere kant van de milieubeweging , http://www.anarchiel.com/ , accessed by the authors on October 14, 2010), in relation to the Bilderberg Conference on D. Estulin (2007, De ware geschiedenis van de Bilderberg-conferentie , Kosmos-Z & K Uitgevers, Utrecht, Antwerp). (Source: Maano Ramutsindela, Marja Spierenburg, Harry Wels: Sponsoring nature: environmental philanthropy for conservation , Earthscan, 2011, p. 49, 63 f.)

- ↑ Also published under the same title in 1st Vintage Books ed, New York 1994, ISBN 0-679-73342-6 ; Online (PDF; pp. 66–75) ( Memento from November 5, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ The linked list of members corresponds to that used by Alexis Schwarzenbach for his book Saving the World's Wildlife. WWF - The first 50 years .

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b WWF in the 70's ( English ) WWF International. Archived from the original on November 17, 2014. Retrieved November 17, 2014.

- ↑ Alexis Schwarzenbach: WWF. The biography . 1st edition. Collection Rolf Heyne, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-89910-491-2 , p. 153 (English: Saving the World's Wildlife. WWF - The first 50 years . London 2011. Translated by Sabine Schwenk).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Günter Murr: Development and options for action by environmental associations in international politics: the example of WWF . In: Series of publications on political ecology . tape 1 . Ökom-Verl., Munich 1996, ISBN 3-928244-23-X , p. 51 .

- ↑ a b c d The 1001: A Nature Trust ( English ) WWF International. Archived from the original on November 19, 2014. Retrieved November 19, 2014.

- ↑ a b c d e f Raymond Bonner: At the hand of man: peril and hope for Africa's wildlife . 1st edition. Alfred A. Knopf, New York 1993, ISBN 0-679-40008-7 , p. 68 (Published simultaneously in Canada: Random House of Canada, Toronto).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa Marja Spierenburg, Harry Wels: Conservative Philanthropists, Royalty and Business Elites in Nature Conservation in Southern Africa . In: Antipode . 42, No. 3, 2010, pp. 647-670. doi : 10.1111 / j.1467-8330.2010.00767.x .

- ↑ Alexis Schwarzenbach: WWF. The biography . 1st edition. Collection Rolf Heyne, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-89910-491-2 , p. 122 f . (English: Saving the World's Wildlife. WWF - The first 50 years . London 2011. Translated by Sabine Schwenk).

- ^ A b c Raymond Bonner: At the hand of man: Peril and hope for Africa's wildlife . 1st edition. Alfred A. Knopf, New York 1993, ISBN 0-679-40008-7 , p. 66 f . (Published simultaneously in Canada: Random House of Canada, Toronto).

- ↑ a b c d Alexis Schwarzenbach: WWF. The biography . 1st edition. Collection Rolf Heyne, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-89910-491-2 , p. 123 (English: Saving the World's Wildlife. WWF - The first 50 years . London 2011. Translated by Sabine Schwenk).

- ↑ Alexis Schwarzenbach: WWF. The biography . 1st edition. Collection Rolf Heyne, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-89910-491-2 , p. 19, 122 f . (English: Saving the World's Wildlife. WWF - The first 50 years . London 2011. Translated by Sabine Schwenk).

- ↑ a b c d David Hughes-Evans: Dedication to Charles De Haes . In: The Environmentalist . 4, No. 1, 1984, pp. 2-4. doi : 10.1007 / BF02337107 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac Stephen Ellis: Of elephants and men: politics and nature conservation in South Africa . In: Journal of Southern African Studies . 20, No. 1, 1994, pp. 53-69. doi : 10.1080 / 03057079408708386 .

- ↑ Alexis Schwarzenbach: WWF. The biography . 1st edition. Collection Rolf Heyne, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-89910-491-2 , p. 19, 123 f . (English: Saving the World's Wildlife. WWF - The first 50 years . London 2011. Translated by Sabine Schwenk).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Maano Ramutsindela, Marja Spierenburg, Harry Wels: Sponsoring nature: environmental philanthropy for conservation . 1st edition. Earthscan, London and New York 2011, ISBN 978-1-84407-904-9 , pp. 47-49, 136 f . ( Online on Google Books - Routledge edition, 2013 ).

- ^ A b c d George Holmes: Conservation's Friends in High Places: Neoliberalism, Networks, and the Transnational Conservation Elite . In: Global Environmental Politics . 11, No. 4, 2011, pp. 1–21. doi : 10.1162 / GLEP_a_00081 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Marja Spierenburg, Harry Wels: Conservative Philanthropists, Royalty and Business Elites in Nature Conservation in Southern Africa . In: Daniel Brockington, Rosaleen Duffy (Ed.): Capitalism and Conservation (= Antipode book series ). Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford 2011, ISBN 978-1-4443-3834-8 , Chapter 7, pp. 179–202 ( in Brockington & Duffy partially accessible online on Google Books [accessed on November 23, 2014] Original publication in: Antipode, vol. 42, no. 3.).

- ↑ a b c d Alexis Schwarzenbach: WWF. The biography . 1st edition. Collection Rolf Heyne, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-89910-491-2 , p. 124 (English: Saving the World's Wildlife. WWF - The first 50 years . London 2011. Translated by Sabine Schwenk).

- ↑ Alexis Schwarzenbach: WWF. The biography . 1st edition. Collection Rolf Heyne, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-89910-491-2 , p. 156 (English: Saving the World's Wildlife. WWF - The first 50 years . London 2011. Translated by Sabine Schwenk).

- ↑ a b WWF International Director Generals 1962-present ( English ) WWF International. Archived from the original on November 17, 2014. Retrieved November 17, 2014.

- ↑ Alexis Schwarzenbach: WWF. The biography . 1st edition. Collection Rolf Heyne, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-89910-491-2 , p. 155 (English: Saving the World's Wildlife. WWF - The first 50 years . London 2011. Translated by Sabine Schwenk).

- ^ A b c Günter Murr: Development and options for action by environmental associations in international politics: the example of WWF . In: Series of publications on political ecology . tape 1 . Ökom-Verl., Munich 1996, ISBN 3-928244-23-X , p. 84 .

- ↑ Alexis Schwarzenbach: WWF. The biography . 1st edition. Collection Rolf Heyne, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-89910-491-2 , p. 133 (English: Saving the World's Wildlife. WWF - The first 50 years . London 2011. Translated by Sabine Schwenk).

- ↑ Alexis Schwarzenbach: WWF. The biography . 1st edition. Collection Rolf Heyne, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-89910-491-2 , p. 124, footnote 39 (p. 330) ( Membership list from 1978 - English: Saving the World's Wildlife. WWF - The first 50 years . London 2011. Translated by Sabine Schwenk).

- ↑ a b Stephen Ellis, Gerrie ter Haar: Worlds of Power: Religious Thought and Political Practice in Africa (= Series in Contemporary History and World Affairs . Volume 1 ). Oxford University Press, New York 2004, ISBN 0-19-522016-1 , pp. 83 (footnote 59 / p. 211: Ellis and ter Haar state here that they are in possession of a membership list of the Club of 1001 and refer to Stephen Ellis in: JSAS, 20, 1 (1994), pp. 53-69.) .

- ↑ John Vidal: WWF International accused of 'selling its soul' to corporations ( English ) In: The Guardian . October 4, 2014. Archived from the original on November 8, 2014. Retrieved on November 8, 2014.

- ↑ a b c d Wilfried Huismann: PandaLeaks: The Dark Side of the WWF . 1st edition. Nordbook, Bremen 2014, ISBN 978-1-5023-6654-2 , pp. 18th f., 94–98, 170–174, 183 (German: Black Book WWF - Dark Shops in the Sign of the Panda . Gütersloh 2012. Translated by Ellen Wagner).

- ↑ a b c d e f Wilfried Huismann: Black Book WWF - Dark business under the sign of the panda . 4th edition. Gütersloh publishing house (Random House GmbH publishing group, Munich), Gütersloh 2012, ISBN 978-3-641-07392-3 (ePub).

- ↑ a b c Marja Spierenburg, Harry Wels: Conservative philanthropists, Royalty and Business Elites in Nature Conservation in Southern Africa . In: Antipode . 42, No. 3, 2010, pp. 647-670, here p. 658. doi : 10.1111 / j.1467-8330.2010.00767.x .

- ↑ a b Maano Ramutsindela, Marja Spierenburg, Harry Wels: Sponsoring nature: environmental philanthropy for conservation . 1st edition. Earthscan, London and New York 2011, ISBN 978-1-84407-904-9 , pp. 48 ( online on Google Books - Routledge edition, 2013 ).

- ↑ Alexis Schwarzenbach: WWF. The biography . 1st edition. Collection Rolf Heyne, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-89910-491-2 , p. 340 ( Membership list from 1978 - English: Saving the World's Wildlife. WWF - The first 50 years . London 2011. Translated by Sabine Schwenk).

- ↑ a b c Presidents - past and present ( English ) WWF International. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved November 29, 2014.

- ^ Lars Langenau: WDR research on the World Wide Fund For Nature: WWF and industry - the pact with the panda . In: Süddeutsche.de . June 24, 2011. Archived from the original on November 23, 2014. Retrieved on November 23, 2014.

- ↑ Alexis Schwarzenbach: WWF. The biography . 1st edition. Collection Rolf Heyne, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-89910-491-2 , p. 124, footnote 40 (p. 330) (English: Saving the World's Wildlife. WWF - The first 50 years . London 2011. Translated by Sabine Schwenk, with reference to: "S. [WWF-Switzerland]," Herr Hoffmann "› 1001 ‹Nature Trust Fund Members, undated [approx. 1974], WWF Switzerland, B4, Trust› 1001 ‹1974-1982).

- ^ A b Matthias Daum: Environmental protection organization - basis versus business . In: Zeit Online . April 24, 2011. Archived from the original on November 27, 2014. Retrieved on November 28, 2014.

- ↑ Alexis Schwarzenbach: WWF. The biography . 1st edition. Collection Rolf Heyne, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-89910-491-2 , p. 148–151 (English: Saving the World's Wildlife. WWF - The first 50 years . London 2011. Translated by Sabine Schwenk).

- ↑ a b Ann O'Hanlon: At the Hand of Man: Peril and Hope for Africa's Wildlife Archived from the original on August 8, 2014. Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. In: Washington Monthly . 25, No. 5, 1993, p. 60. Retrieved November 18, 2014.

- ^ Raymond Bonner: At the hand of man: Peril and hope for Africa's wildlife . 1st edition. Alfred A. Knopf, New York 1993, ISBN 0-679-40008-7 , p. 68 f . (Published simultaneously in Canada: Random House of Canada, Toronto).

- ↑ Stephen Ellis, Gerrie ter Haar: Worlds of Power: Religious Thought and Political Practice in Africa (= Series in Contemporary History and World Affairs . Volume 1 ). Oxford University Press, New York 2004, ISBN 0-19-522016-1 , pp. 83 .

- ^ Günter Murr: Development and options for action by environmental associations in international politics: the example of WWF . In: Series of publications on political ecology . tape 1 . Ökom-Verl., Munich 1996, ISBN 3-928244-23-X , p. 51, footnote 212 .

- ^ A b c Raymond Bonner: At the hand of man: Peril and hope for Africa's wildlife . 1st edition. Alfred A. Knopf, New York 1993, ISBN 0-679-40008-7 , p. 69 f . (Published simultaneously in Canada: Random House of Canada, Toronto).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Rosaleen Duffy: Killing for Conservation: Wildlife Policy in Zimbabwe (= African issues ). James Currey Publishers, Oxford 2000, ISBN 0-85255-846-5 , pp. 60 f . ( Online on Google Books [accessed November 23, 2014]).

- ^ Raymond Bonner: At the hand of man: Peril and hope for Africa's wildlife . 1st edition. Alfred A. Knopf, New York 1993, ISBN 0-679-40008-7 , p. 69 f., 72, 74 f . (Published simultaneously in Canada: Random House of Canada, Toronto).

- ^ A b Raymond Bonner: At the hand of man: Peril and hope for Africa's wildlife . 1st edition. Alfred A. Knopf, New York 1993, ISBN 0-679-40008-7 , p. 70 f . (Published simultaneously in Canada: Random House of Canada, Toronto).

- ↑ Marja Spierenburg, Harry Wels: Conservative philanthropists, Royalty and Business Elites in Nature Conservation in Southern Africa . In: Antipode . 42, No. 3, 2010, pp. 647-670, here: p. 660, footnote 14 / p. 666. doi : 10.1111 / j.1467-8330.2010.00767.x . “See also Eveline Lubbers from Buro Jansen en Janssen on http://www.burojansen.nl/artikelen_item.php?id=204 (accessed 10 May 2007). Thanks to Stephen Ellis for bringing her name to our attention "

- ^ Eveline Lubbers, Wil van der Schans: British Aerospace wapent zich tegen acties. ( Dutch ) burojansen.nl. April 5, 2004. Archived from the original on November 26, 2014. Retrieved on November 26, 2014.

- ↑ a b c Alexis Schwarzenbach: WWF. The biography . 1st edition. Collection Rolf Heyne, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-89910-491-2 , p. 209, 212 (English: Saving the World's Wildlife. WWF - The first 50 years . London 2011. Translated by Sabine Schwenk).

- ↑ a b c d Raymond Bonner: At the hand of man: peril and hope for Africa's wildlife . 1st edition. Alfred A. Knopf, New York 1993, ISBN 0-679-40008-7 , p. 78 f . (Published simultaneously in Canada: Random House of Canada, Toronto).

- ^ Pretoria inquiry confirms secret battle for the rhino ( English ) In: The Independent . January 18, 1996. Archived from the original on November 25, 2014. Retrieved November 25, 2014.

- ↑ a b Maano Ramutsindela, Marja Spierenburg, Harry Wels: Sponsoring nature: environmental philanthropy for conservation . 1st edition. Earthscan, London and New York 2011, ISBN 978-1-84407-904-9 , pp. 51 ( online on Google Books - Routledge edition, 2013 ).

- ^ Ros Reeve, Stephen Ellis: An insider's account of the South African Security Forces' role in the ivory trade . In: Journal of Contemporary African Studies . 13, No. 2, 1995, pp. 227-243. doi : 10.1080 / 02589009508729574 .

- ↑ Alexis Schwarzenbach: WWF. The biography . 1st edition. Collection Rolf Heyne, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-89910-491-2 , p. 209, 212, footnote 7 / p. 334 (English: Saving the World's Wildlife. WWF - The first 50 years . London 2011. Translated by Sabine Schwenk).

- ↑ a b c d e Raymond Bonner: At the hand of man: peril and hope for Africa's wildlife . 1st edition. Alfred A. Knopf, New York 1993, ISBN 0-679-40008-7 , p. 79 f., Footnote for p. 79 / p. 296 (Published simultaneously in Canada: Random House of Canada, Toronto - Referenced: Robert Powell, July 6, 1989; Stephen Ellis, Africa Confidential, July 28, 1989; Stephen Ellis, The Independent, January 8, 1991).

- ↑ Wilfried Huisman: PandaLeaks: The Dark Side of the WWF . 1st edition. Nordbook, Bremen 2014, ISBN 978-1-5023-6654-2 , pp. 107 f . (German: Black Book WWF - Dark Shops in the Sign of the Panda . Gütersloh 2012. Translated by Ellen Wagner, footnote 24 / p. 252: According to Stephen Ellis in a television interview with Wilfried Huismann on March 7, 2011).

- ^ Raymond Bonner: At the hand of man: Peril and hope for Africa's wildlife . 1st edition. Alfred A. Knopf, New York 1993, ISBN 0-679-40008-7 , p. 80 f . (Published simultaneously in Canada: Random House of Canada, Toronto).

- ^ Raymond Bonner: At the hand of man: Peril and hope for Africa's wildlife . 1st edition. Alfred A. Knopf, New York 1993, ISBN 0-679-40008-7 , p. 78–81 (published simultaneously in Canada: Random House of Canada, Toronto).

- ↑ a b c Marja Spierenburg, Harry Wels: Conservative philanthropists, Royalty and Business Elites in Nature Conservation in Southern Africa . In: Antipode . 42, No. 3, 2010, pp. 647-670; here: p. 661, footnote 15 / p. 666. doi : 10.1111 / j.1467-8330.2010.00767.x .