Yagan (Noongar)

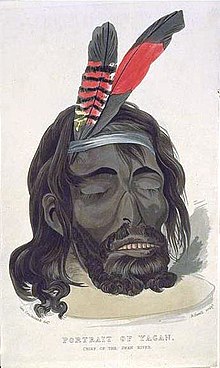

The graphic was created after Yagan's head was cut off and smoked to preserve it. During this process, the shape of the head changed significantly. George Fletcher Moore therefore pointed out that the head is not a true-to-life representation of Yagan. Yagan's face was actually plump and strong.

Yagan (spr. ˈJæɪ gən ) (* probably 1795 ; † July 11, 1833 in Belhus, a suburb of Perth ) was a warrior of the Noongar , an Aboriginal tribe of Australia . He played an essential role in the resistance of the people of the region around Perth to the occupation of the land by Europeans. Yagan was shot dead by a young settler in July 1833 after leading a series of attacks on whites and receiving a bounty for his capture or killing . Yagan's death has entered Western Australian folklore as a symbol of the conflicts between the indigenous peoples of Australia and the European settlers .

Yagan's head was brought to London after his shooting and was initially exhibited there as an anthropological curiosity. After being kept in museum storage for over a century, the head was buried in a Liverpool cemetery in 1964 . In 1993 this grave was located and four years later the head was exhumed and brought back to Australia. The appropriate burial ceremony for this head has long been controversial among the indigenous people of the Perth area. The skull of Yagan was buried in a traditional Aboriginal funeral ceremony near Perth in the Swan Valley in July 2010, 177 years after his death , at the spot where he was shot.

Life

Tribal affiliation and family

Yagan belonged to the Whadjuk-Noongar tribe and, according to the information provided by Robert Lyon, belonged to an Aboriginal tribe of about 60 people, which Lyon referred to as " Beeliar ". Robert Lyon was a contemporary Australian settler who sought an understanding with the Aborigines. However, its information is not always reliable. Today it is more likely that the Beeliar was just a family group within a larger tribe, which was called the Beelgar after Daisy Bates . According to information from Robert Lyons, the Beeliar Association was wandering an area that stretched from the south bank of the Swan and Canning Rivers to Mangles Bay . Obviously, the group had much more extensive territorial claims, reaching in the north to Lake Monger and northeast to the Helena River . They were also able to roam unusually freely in neighboring areas, possibly due to kinship or marital relationships with the neighboring tribes. Like all Aboriginal tribes , the Beeliar did not practice agriculture in the European sense. They were gatherers and hunters who only stayed longer in one place when there was plenty of food on site.

Yagan was probably born around 1795. His father was Midgegooroo, an elder of the Beeliar, and his mother was probably one of Midgegooroo's two wives. Yagan was possibly a ballaroke in the Noongar classification . According to historian Green, he had a wife and two children, but most historians believe that Yagan was unmarried and childless. He is described as larger than average and impressively stocky. A tattoo on his right shoulder identified him as a "man of high rank in tribal law". He was generally considered to be the strongest representative of his tribe.

Contemporary documents spelled his name Egan or Eagan , suggesting that the correct pronunciation was closer to / 'iː gən / than today's version /' jæɪ gən / .

The beginning of colonization by Europeans

Yagan was about 35 years old when British settlers began to settle in the Noongar area in 1829. One of the foundations of the settlers was the Swan River Colony , whose settlement area was on the land of the Beeliar.

During the first two years that this settlement existed, relations between European settlers and Aboriginal people were largely friendly. The two groups were not yet competing for the land's resources, and the Noongar understood the white settlers as Djanga, or returned spirits of the Noongar ancestors. However, as the settlement grew, so did the conflicts between the two cultures. The settlers were of the opinion that the Noongar, as nomads, had no right of ownership of the land that they roamed in their traditional way of life. They therefore felt they had the right to fence in land for grazing and agriculture. The Noongar were increasingly denied access to their traditional hunting grounds and holy sites. As early as 1832, access to the Swan or Canning River was almost impossible for the group to which Yagan belonged, as the settlers preferred to settle along the river banks.

The Noongar responded to the loss of their hunting and gathering areas by increasingly harvesting the settlers 'arable land or by killing the settlers' cattle. They also began to appreciate the settlers' previously unknown foods. The increasing appropriation of flour or other food by the Noongar was a punishable theft according to the standards of the settlers and also represented a potentially threatening problem for the settlement. The traditional land use of the Noongar also included regular burning of areas. This burning off not only scared off hunted game, but also encouraged the growth of a number of plants that played a role in the Aboriginal diet. It is a form of land management that is now partially practiced again in Australia because it is a form of land management appropriate to the conditions on this continent. From the settlers' point of view, the fires posed a threat to their cropland and houses.

The first conflicts

The first significant clash between Aboriginal and white settlers in western Australia occurred in December 1831. Thomas Smedley, a worker on Archibald Butler's farm, ambushed some Aborigines who were harvesting a potato field from the settlers and shot one of them. The dead belonged to the Yagan family association. A few days after this incident, Yagan, Midgegooroo, and a few others raided Archibald Butler's farmhouse. When they found the front door of the house locked, they began pounding a hole in the adobe walls. Inside was Erin Entwhistle, another worker on the butler farm, with his two sons, Enion and Ralph. After hiding his sons under a bed, Entwhistle opened the door to negotiate with the attackers. He was immediately pierced by the spears of Yagan and Midgegooroo.

Noongar tribal law required that a murder be atoned for by the death of a member of the killer's family . The dead person did not necessarily have to be the murderer. The murder of Erin Entwhistle could therefore be seen from the point of view of the Noongar, who presumably regarded the people belonging to the Butler farm as a family group, as the appropriate atonement for the previous murder of their own family member. For the white settlers, it was an unprovoked murder of an innocent man.

In June 1832, Yagan led an Aboriginal attack on two workers who were sowing wheat in a field at Canning near Kelmscott . One of the two men managed to escape. The second, named William Gaze, was wounded and later died from his injuries, which had probably become infected . Yagan was then declared an outlaw . A reward of £ 20 was offered for his capture . He managed to avoid arrest until early October 1832 when a group of fishermen Lured Yagan and two of his friends into their boat and took them out to sea. The three Noongar were initially locked in the Perth Guard House and later transferred to the Round House near Fremantle . Yagan was sentenced to death. The fact that the death sentence was not carried out was due to Robert Lyon, who argued that Yagan was only defending his land against occupation by white settlers and was therefore not a criminal but a prisoner of war and should therefore be treated as such. Until the governor's decision on the assessment of the case, at the suggestion of John Septimus Roe Yagan and his two friends were exiled to the island of Carnac. There they were under the supervision of Robert Lyon and two soldiers.

Lyon was convinced that he could civilize Yagan and convert him to Christianity . As the Yagan enjoyed a high reputation within his tribe, Lyon was convinced that through Yagan the Noongar could be convinced to recognize the authority of the whites. To achieve this, Lyon spent many hours with Yagan to learn, among other things, his language and his view of life. Yagan and his companions escaped from the island after a month. They managed to steal an unguarded dinghy and row it to Woodman Point on the mainland. Attempts to detain the three men were not made.

Other Noongar family groups lived in the King George Sound region and there remained friendly relations between the settlers and the Aborigines. When Gyallipert and Manyat, two Noongar from this region, visited Perth in January 1833, the two settlers Richard Dale and George Smythe organized a meeting between the local Noongar and these two men. They connected the hope that the example of the Noongar from King George Sund could convince the local Noongar to establish a similarly good relationship with the Swan River Colony. On January 26, 1833, Yagan led a group of ten formally armed men who met the two men from King George Sound near Lake Monger. The two groups exchanged weapons and held a corroboree , although they apparently could not converse due to dialect differences. Yagan and Gyallipert then competed against each other in a javelin throwing competition, in which Yagan proved that he could hit a stick 25 meters away with his spear.

Gyallipert and Manyat stayed in the Perth region for a few weeks and Yagan obtained permission to hold another corroboree. The meeting place this time was the garden of the post office in Perth. At dusk on March 3, the Perth Noongar and King George Sund met, chalked their bodies and performed a number of their traditional dances, including the kangaroo hunting dance. The local newspaper , the Perth Gazette, wrote that Yagan was not only the master of ceremonies that evening, but also distinguished himself with “physical grace and dignity”.

During the months of February and March 1833, Yagan was involved in a number of minor confrontations between Noongar and white settlers. In February, settler William Watson complained that Yagan had forcibly opened the door of his house, asked for a rifle , appropriated handkerchiefs and that Watson had to give him and his companions flour and bread . In March, Yagan was part of a group of Noongar who received biscuits from a military contingent led by Lieutenant Norcott. When Lieutenant Norcott tried to limit the amount of biscuits given to the Noongar, Yagan threatened him with the spear. A little later that month, Yagan and a group of other Noongar broke into Watson's home again. William Watson himself was absent and the Noongar did not leave the house until Watson's wife called their neighbors to help. For the Perth Gazette , this was the reason to rave about the “reckless daring of this desperado ” who “risks his life for the value of a pin [...]. For the most insignificant cause he would take the life of anyone who provokes him. He is the one who is behind every mischief ”.

Declared an outlaw

On the night of April 29, 1833, a group of Noongar broke into a shop in Fremantle . They were surprised by Peter Chidlow who shot them. Domjum, one of Yagan's brothers, was seriously injured and died in prison a few days later. The rest of the group moved from Fremantle to Preston Point, where Yagan was heard vowing revenge for death. Fifty to sixty Noongar gathered in Bull Creek within sight of the High Road, where they met a group of settlers loading wagons with supplies. Later that day they ambushed the leading car and killed Tom and John Velvick with spears. The Noongar tribal law required only one man to die to atone for Domjum. The Aboriginal Munday later stated that both Velvicks were killed because they had previously mistreated Aboriginal people. In fact, the Velvicks had previously been convicted of attacking Aboriginal and colored sailors. Alexandra Hasluck named the desire to steal the supplies as an important motive for the attack, but this is rejected by other researchers.

Lieutenant Governor Frederick Irwin declared Yagan, Midgegooroo and Munday outlaws for murdering the Velvicks. A reward of £ 20 each was offered for the capture of Midgegooroo and Munday. On the other hand, anyone who succeeds in capturing or killing Yagan should receive 30 pounds. The Aboriginal Munday successfully appealed against this. It seems to have been clear to Midgegooroo and Yagan that the settlers would now hunt them down. Their group immediately left the region they traditionally roamed and headed north towards the Helena River . Midgegooroo was caught there four days after the two Velvicks were murdered. After a brief, informal trial, Midgegooroo was executed by firing squad . Yagan avoided capture for another two months.

In late May, George Fletcher Moore met Yagan on his farm in the Upper Swan area, and the two first spoke in pidgin English. Yagan switched to his own language during this conversation, and Moore noted in his later published diary:

"Yagan stepped forward and leaning with his left hand on my shoulder while he gesticulated with the right, delivered a sort of recitation, looking earnestly into my face. I regret that I could not understand it. I thought from the tone and manner that the purport was this: You came to our country; you have driven us from our haunts, and disturbed us in our occupations. As we walk in our own country we are fired upon by the white men; why should the white men treat us so? "

“Yagan came closer, put his left hand on my shoulder, looked at me seriously and fell into a kind of recitation while he gestured with the other hand. I still regret not being able to understand him. From the tone of voice and the way he said it, however, I thought that he wanted to tell me this:

You have come to our country; you have driven us from our hunting grounds and destroyed our way of life. When we roam our own country today, the white men shoot us. Why do the white men treat us like that? "

Since Moore spoke very little of Yagan's language, the historian Hasluck has pointed out, however, that this diary entry reflects more the moral feelings of a European settler in the first half of the 19th century than what Yagan may have thought and felt at that time . Yagan then asked Moore whether Midgegoroo was still alive. Moore himself gave no answer to this question. One of Moore's workers claimed in his place that Midgegooroo was being held captive on Carnac Island. Yagan replied with the threat: “White man shoot Midgegooroo, Yagan kill three” (White man shoots Midgegooroo, Yagan kills three). Moore himself made no attempt to capture Yagan, but reported to the nearest justice of the peace that Yagan was in the region. In his diary , George Fletcher Moore noted:

"The truth is, every one wishes him taken, but no one likes to be the captor ... there is something in his daring which one is forced to admire."

"It is true that everyone [the white settlers] wants them [Yagan] to be caught, but nobody wants to be the catcher ... His [Yagan's] daring makes one admire him."

Yagan's death

On July 11, 1833, north of Guildford, there was another encounter between whites and Yagan. Two brothers, William and James Keates, who were both teenagers, drove a herd of cattle along the banks of the Swan River. They met a group from Noongar who were on their way to Henry Bull's house to get their ration of flour. There was also Yagan in the group. The brothers and Yagan knew each other through previous encounters and had been on friendly terms with each other. The Keates brothers therefore suggested that Yagan should stay with them so as not to expose themselves to the risk of capture at Henry Bull's house.

Yagan accepted the proposal and stayed with the two brothers throughout the morning. In the course of the morning, however, the two brothers decided to kill Yagan and then collect the reward. When William Keates tried to aim at Yagan and shoot him unnoticed, the rifle blocked and the attempt failed. Before the return of the other Noongar from Henry Bull's mill, the two brothers had no opportunity to kill Yagan. It was only when the Noongar wanted to separate from the brothers in order to move on that the brothers were offered another shot. William Keates shot Yagan and James Keates another Aboriginal named Heegan when he hurled a spear in their direction. The two brothers ran towards the river. However, William Keates was overtaken by the surviving Noongar and killed by their spears. James Keates was able to swim across the river and bring a group of armed settlers from Henry Bull's property.

George Fletcher Moore also recorded this incident in his diary and reported that a group of soldiers passed nearby shortly after the incident. Moore believed that it was their proximity that prevented the Noongar from recovering the bodies of Yagan and Heegan. When the group of armed settlers arrived a little later, they found Yagan dead and Heegan dying. Heegan had severe head injuries and was groaning on the floor. One of the settlers put the rifle on Heegan's head and shot him. Moore leaves open whether this was out of vengeance or compassion. Yagan's head was severed from his body and his back was skinned to keep his tribal tattoos as a trophy . Both bodies were buried in the immediate vicinity.

James Keates, who received the reward for Yagan's shooting, was largely criticized for his behavior. The Perth Gazette called the shooting of Yagan a rash and treasonous act. The newspaper also wrote that it was repugnant and abhorrent to praise the process as meritorious. James Keates left the colony the following month. The reasons are unknown. It is not unlikely, however, that he feared fatal retribution from the Noongar.

Yagan's head

Exhibition and funeral

Yagan's head had first been brought to Henry Bull's house. George Fletcher Moore saw the head there and sketched it several times in his journal. He already stated at the time that this head could possibly be exhibited in a museum in Great Britain. Around the head before decay to preserve, he was hung up in a hollow tree and several weeks over a eucalyptus fire smoked .

In September 1833 the Ensign took Robert Dale Yagan's head with them to London . According to the historian Paul Turnbull, Robert Dale convinced the governor in charge, Irwin, to leave him with the head as an "anthropological curiosity". Upon arriving in London, Dale approached a number of anatomists and phrenologists and tried to sell them the head for £ 20. When no one showed any interest, he left the head to Thomas Pettigrew for a year . Pettigrew was a doctor and antiquarian who was known in London society for hosting private evening parties, at which he performed autopsies on ancient Egyptian mummies , among other things . Pettigrew showed Yagan's head on a table in front of a panorama of King George Sound drawn from Dale's sketches . To increase the effect of the head, the head was decorated with a headband and cockatoo feathers .

Thomas Pettigrew also had the head examined by a phrenologist . The examinations were made more difficult because the skull bones at the back of the head showed fractures . As expected, the phrenologist's findings corresponded to the contemporary European image of the characteristics of the indigenous population of Australia and were part of a publication by Dale on King George Sound and the neighboring country, which was sold by Pettigrew, among others, as a souvenir of the guests at his evening events. The cover of the pamphlet was a hand-colored aquatint by George Cruikshank showing Yagan's feathered head.

In early October 1835, Thomas Pettigrew returned both Yagan's head and the panorama painting to Robert Dale. Dale was living in Liverpool at the time . He handed both over to the Liverpool Royal Institution, where the head may have been exhibited together with other similar head preparations and wax models. In 1894 this collection was closed and Yagan's head was given to the Liverpool Museum . It is relatively certain that this institution never showed its head in its showrooms. The head was probably only kept in the museum's storerooms.

At the beginning of the 1960s, Yagan's head showed clear signs of deterioration and in April 1964 it was decided that the head should be disposed of. On April 10, 1964, Yagan's head was placed in a plywood box along with a Peruvian mummy and a Maori head and buried in Everton Cemetery in Liverpool. In the following years the neighboring graves were occupied and in 1968 a local hospital left the bodies of 20 stillbirths and two babies who had not survived the first 24 hours of their lives in the grave that contained the plywood box containing the remains of Yagan's head , bury. This was possible because the plywood box was buried very deep in 1964.

Fight for repatriation

It cannot be precisely dated when Noongar groups took steps to get Yagan's head back. The first activities can be traced back to at least the early 1980s. According to Aboriginal belief, a dead spirit remains connected to the earth if its body is not completely and in one place buried. A burial of Yagan's head where the torso was buried would mean that his spirit would finally be able to embark on the eternal journey.

In the early 1980s, the Noongar were unaware of what had happened to Yagan's head after Thomas Pettigrew returned it to Robert Dale. Ken Colbung was hired by the elders of the Noongar tribe to investigate the matter. Inquiries at various British museums about the whereabouts of the head were initially unsuccessful. In the early 1990s, Ken Colbung managed to win the support of archaeologist Peter Ucko from the University of London . With funds from the Australian government, Cressida Fforde, one of Ucko's co-workers, was commissioned to research publications of the time for information about the whereabouts of Yagan's head. This proved successful. In December 1993 it was known that the head had been given to the Liverpool Museum and that the head had been buried in 1964. In April 1994, Colbung applied for permission to exhume the head under Section 25 of the Burial Act 1857. Under British law, this would have required the consent of the closest relatives of the 22 small children who were also buried in the grave. With the argument that the exhumation was of great personal importance for Yagan's relatives who were still alive, and that the recovery was also of importance for the Australian nation, Ken Colben's lawyers tried to suspend this demand.

Meanwhile, disputes had arisen within Perth's Noongar community. The commissioning of Ken Colbung, who was not a pure-blood Aboriginal, has been questioned by a number of Elders. One Noongar even filed an official complaint with Liverpool City Council about Colbt's role in the planned exhumation and repatriation of Yagan's head. The debate within the Noongar community as to which cultural qualifications someone who takes care of the recovery of the head should have was led in part with bitterness and commented on in the media. A public meeting was held in Perth on July 25, 1994, at which the parties involved at the time agreed that the disputes would be settled and that they would cooperate in order to achieve a return of the head as quickly as possible. Ken Colbung was allowed to continue his work; a "Yagan Steering Committee" was set up as an advisory board.

In January 1995, the UK Home Office decided that she had to insist on the consent of the relatives of the 22 young children buried in the grave before an exhumation could take place. The home office contacted five family members whose address could be found. Only one family gave unreserved consent. On June 30, 1995, Ken Colbung was informed that no permit could be given for the exhumation.

The Yagan Steering Committee met on September 21, 1995 and decided that it would first focus on gaining the support of Australian and British politicians. This procedure resulted in an invitation for Colbung to Great Britain at British government expense. Colbung arrived in the UK on May 20, 1997. His visit to Great Britain received extensive coverage in the British press. This increased political pressure on the UK government to seek a solution as well. During Colbung's stay in Great Britain, the Australian Prime Minister John Howard was on a state visit to Great Britain. During this visit, Ken Colbung succeeded in forcing a conversation with John Howard and thus also received the personal support of the Australian Prime Minister.

exhumation

While Colbung was in the UK, Martin and Richard Bates were commissioned to conduct a geophysical survey of the burial site. Using electromagnets and ground penetrating radar , they were able to locate the approximate position of the plywood box in the tomb. In their subsequent report, they also pointed out the possibility of reaching the plywood box from a neighboring grave without disturbing the quiet of the dead of the toddlers buried above the plywood box. The investigation was forwarded to the UK Home Office and led to further discussions between the UK and Australian governments.

Meanwhile, the UK Home Office received an unknown number of letters objecting to Ken Colbung's role in the repatriation of the head. The Home Office reached out to the Australian government to verify that Ken Colbung was right to play the leading role in the process. In response, Colbung asked the Noongar elders to have the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC) confirm his role. The ATSIC then met in Perth and reaffirmed Ken Colbt's mandate.

Despite these internal disputes, Ken Colbung continued to try to enforce the exhumation. He asked that the exhumation be carried out before July 11, 1997, if possible, so that the 164th anniversary of Yagan's death could be used for an appropriate celebration. His request was not granted and on the anniversary Colbung only held a small memorial service at the burial site in Liverpool cemetery. On July 15, 1997, he returned to Australia empty-handed.

Without Colbung's knowledge, the UK finally began to exhume Yagan's head. For this purpose, a shaft six feet deep was dug on the side of the grave and dug from there horizontally in the direction of the place where one suspected the plywood box. The exhumation could take place without disturbing the remains of the other people buried there. The next day, the University of Bradford forensic paleontologist confirmed that the find was Yagan's head. The fractures at the back of the head, which were described in detail in contemporary reports, coincided with the excavated skull. The skull was kept in a museum until August 29, when it was given to Liverpool City Council.

repatriation

On August 27, 1997, a Noongar delegation traveled to Great Britain to receive the skull. The delegation consisted of Ken Colbung, Robert Bropho , Richard Wilkes and Mingli Wanjurri-Nungala, and it was originally intended to consist of more Noongar members. The funding of the Noongar's trip by official agencies of the British Commonwealth failed shortly before their departure, so the delegation had to be limited to four people. The handover was delayed, however, as a Noongar named Corrie Bodney filed for an injunction with the Supreme Court of Western Australia . Citing his family's sole responsibility for Yagan's remains, he declared the exhumation illegal and denied the existence of any tradition or belief that required the exhumation and return to Australia.

It was not legally possible for the Supreme Court of Western Australia to issue an urgent decision that would have been binding on the British government. Instead, he turned to the government of the Australian state of Western Australia to lodge a preliminary, formal objection to the surrender with the British government. The British government then actually stopped the handover until Bodney's objection was decided. On August 29, the court dismissed the lawsuit on the grounds that Bodney had previously consented to the act and a Noongar senior and an anthropologist heard as witnesses denied Bodney's claim to sole responsibility.

On August 31, 1997, Yagan's skull was presented to the Noongar delegation in a ceremony at Liverpool Town Hall . On the morning of that day Diana, Princess of Wales had a fatal accident and the words with which Ken Colbung received the skull were linked to this accident. Colbung had said at the handover

- The British did wrong things and because of that they suffer. You have to learn to live with this suffering as we had to learn to live with. That’s the world.

Ken Colben's comment sparked a lot of media coverage in Australia; Australian newspapers received numerous letters from their readers expressing shock and annoyance at these statements. Ken Colbung later claimed that his comment had been misinterpreted.

The discussion about the appropriate burial site

Even after his return to Perth, Yagan's head continued to be the source of controversy and conflict. A committee was appointed for the reburial of the head, chaired by Richard Wilkes. However, the funeral was delayed due to discussions between the Noongar elders. The exact burial location of Yagan's torso was unknown and the elders disagreed about the importance of burying the head where the body was buried.

Several attempts were made to find the exact burial site of Yagan's torso. It was generally believed that the grave was located on property on West Swan Road in Belhus, one of the outer suburbs of Perth. Investigations were carried out there in both 1998 and 2000. However, a grave could not be found. This led to discussions about whether the head could be buried separately from the body. Richard Wilkes, the chairman of the funeral committee argued that it was sufficient to bury the head where Yagan was killed. The “ dreamtime spirits” would then merge the physical remains. Official Australian government agencies also interfered in this discussion. As early as 1998 the "Western Australian Planning Commission" and the "Department of Aboriginal Affairs" jointly published a document entitled "Yagan's Gravesite Master Plan" (guideline for Yagan's burial site). In this report, considerations were made as to how the property on which Yagan's body was suspected should be dealt with in the future. It was proposed to turn the property into a traditional burial site for Perth's indigenous people. The property was to be administered by the authority that was also responsible for the other cemeteries in Perth.

The head was kept in a bank safe for some time and then handed over to forensic experts who tried to reconstruct Yagan's facial features based on the skull. The head has since been in the state morgue of Western Australia. The burial of the head has been postponed several times and is still the cause of a number of conflicts between individual Noongar groups. The funeral committee has been repeatedly accused of acting against the wishes of the Noongar community and of using the head to build parks and monuments in memory of Yagan. Richard Wilkes countered these attacks that the members of the committee were related to Yagan and therefore wanted an appropriate burial. The funeral has so far only been delayed because of the search for the right burial site. In the meantime, alternative proposals for burial have also been discussed. For example, at the beginning of 2006, Ken Colbung suggested having one's head burned and the ashes scattered on the Swan River. In June 2006, Richard Wilkes announced that the head would be buried by July 2007.

On July 10, 2010, Yagan's head was solemnly buried. The ceremony in Belhus was attended by around 300 people, including Elders the Noongar and Colin Barnett , the Prime Minister of Western Australia.

The Yagan warrior in Australian culture

Yagan as a cartoon character: Alas Poor Yagan

On September 6, 1997, the Australian newspaper "The West Australian" published a comic by Dean Alston with the title "Alas Poor Yagan" (based on Shakespeare's Hamlet, Act 5, Scene 1, to be translated as "Oh, poor Yagan") who was very critical of the fact that the return of Yagan's head was the cause of numerous conflicts within the Noongar community instead of unifying them. The way in which the comic dealt with the subject could well be interpreted as insulting aspects of the Noongar culture. The comic also questioned the motives and legitimacy of non-pureblood Aboriginal people involved in the repatriation and discussion of the burial of the head. For a group of Noongar elders, this was the reason to complain to the Australian Equality Agency. The agency actually ruled that the comic was inappropriately commenting on Noongar beliefs. However, he does not violate the law against racial discrimination. The Federal Court of Australia decided this too.

The Yagan Monument

Members of the Noongar community had already campaigned in the mid-1970s for a memorial to be erected in memory of Yagan. The memorial was to be erected on the occasion of the 150th anniversary of the founding of the western Australian state in 1979. However, the Noongar community's proposal was not heard. Charles Court, the current minister of state of this Australian state, followed the advice of historians at the time, who classified Yagan as too insignificant for Western Australian history to justify a monument. Ken Colbung claims that the funds that were available were instead used to renovate the burial site of James Stirling, the first governor of Western Australia. Despite this rejection, the Noongar community stuck to the idea of a memorial to Yagan. They formed a committee and started raising money for such a monument. The Australian sculptor Robert Hitchcock was commissioned to design the monument. Hitchcock created a life-size bronze statue of Yagan naked with a spear carried over his shoulders. The memorial was erected on Heirisson Island in the Swan River near Perth and opened to the public on September 11, 1984.

In 1997, just a week after Yagan's head returned to Perth, the memorial's head was cut off and stolen. This was repeated a second time after the monument was restored. Since the second renovation, the monument has remained undamaged to this day. The perpetrators could not be found despite an anonymous letter of confession alleging that the damage to the monument was in revenge for Ken Colbung's comments at the handover, which referred to the accidental death of Diana, Princess of Wales.

In 2002, however, suggested Janet Woollard, a member of the West Australian state parliament, that the statue should be redesigned, covering the genitals . The proposal was also taken up by Richard Wilkes in November 2005. He argued that this change helped to give a more historically correct picture of Yagan. Yagan probably wore a loincloth for most of the year. The erection of another monument is also currently being considered. The head shape of this new monument should correspond to the findings from forensic facial reconstruction .

Literature and film

In 1964, Mary Durack published a youth novel that retold the life of Yagans in fictional form. The book was titled The Polite Savage: Yagan of the Swan River . When it was reissued in 1976, the title of the book was changed to "Yagan, the Bibbulmun", as the original title was seen as racist because of the use of the term "the savage".

The repeated beheading of Yagan Memorial in 1997 prompted the Aboriginal writer Archie Weller a short story entitled Confessions of a bounty hunter (English title: Confessions of a Headhunter ) to publish. Weller later worked with film director Sally Riley to develop a script based on this narrative. A 35-minute short film with the same title was created from this script in 2000. Both the film and the script won awards in Australia.

In 2002, the South African- born poet John Mateer , who now lives in Australia, published his fourth collection of poems entitled " Loanwords ". The collection of poems is divided into four parts. The third part is titled In the Presence of a Severed Head (In the Presence of a Severed Head ). The poems reproduced there deal with Yagan.

Other cultural references

In September 1989, an early-ripening variety of barley was put on the market, which is called "Hordeum vulgare (Barley) cv Yagan". The Australian Department of Agriculture was the breeder of this type of barley, which thrives particularly well on sandy soils. The variety is called "Yagan" in normal usage and is named in memory of the Noongar warrior. With the naming, the "Australian Department of Agriculture" followed the custom that grains cultivated in Western Australia are named after historical figures of Western Australian history.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Yagan to be reburied after nearly 2 centuries. Information on www.abc.net.au from July 10, 2010

- ↑ Bourke, Michael: Chapter 3: Yagan 'The Patriot' and 'Governor' Weeip. In: On the Swan. University of Western Australia Press, Nedlands, Western Australia 1987, ISBN 0-85564-258-0 .

- ^ A b Sylvia K. Hallam, Lois Tilbrook: Aborigines of the Southwest Region, 1829-1840 (= The Bicentennial Dictionary of Western Australians. Volume VIII). University of Western Australia Press, Nedlands, Western Australia 1990, ISBN 0-85564-296-3 .

- ↑ The Australian landscape was significantly shaped by the presence of the Aborigines. Collecting specific plants with the digging stick often encouraged their reproduction. The regular burning of tracts of land practiced by Aborigines was far more distinctive. This form of land management prevented the emergence of scrub and led to the spread of grassland. According to estimates by European settlers of the 19th century, who were still witnesses of the traditional way of life of Aborigines, scorching took place at least every five years. See also Geoffrey Blainey: Triumph of the Nomads . Sydney 1982, ISBN 0-7251-0412-0 , pp. 67-84.

- ↑ a b Neville Green. Aborigines and White Settlers in the Nineteenth Century . In: Tom Stannage (Ed.): A New History of Western Australia . University of Western Australia Press, Nedlands, Western Australia 1981, ISBN 0-85564-170-3 , pp. 72-123.

- ^ Neville Green: Yagan, the Patriot . In: Lyall Hunt (Ed.): Westralian Portraits . University of Western Australia Press, Nedlands, Western Australia 1981, ISBN 0-85564-157-6 .

- ↑ It is (again) practiced in Australian national parks. The controlled, rapid scarfing of dried up vegetation, which usually does not generate high levels of heat, prevents larger and more devastating bush fires from occurring and, among other things, promotes the germination of seeds. In fact, the seeds of some plants must have been exposed to fire before they can germinate

- ↑ In traditional European agriculture, for example, stubble fields were scorched so that the ashes fertilized the fields and weeds were destroyed. Very few settlers realized that the targeted Aboriginal bushfires were a comparable form of land management. To do this, it would first have been necessary to recognize that nomads also practice targeted and planned land use. This realization did not gain acceptance until the second half of the twentieth century.

- ^ A b Neville Green: Broken spears: Aborigines and Europeans in the Southwest of Australia . Focus Education Services, Perth, Western Australia, 1984, ISBN 0-9591828-1-0 .

- ↑ Due to the relative isolation of the individual family groups, the Aborigines in Australia spoke at least 300 different languages . Strong dialect differences are not counted here. Even the language of two neighboring groups could differ so much that they could not understand each other. The language differences between the two Aboriginal groups who lived on the opposite coasts of Sydney's natural harbor were so great that conversation between them was impossible. See also Blainey, p. 31.

- ^ The Perth Gazette. March 16, 1833. The newspaper wrote literally: “ [Yagan] was master of ceremonies and acquitted himself with infinite grace and dignity. ”

- ↑ The Perth Gazette , March 2, 1833. Literally called him the Perth Gazette as " the reckless daring of this desperado who sets his life at a pin's fee" and then commented further: "For the most trivial offense [...] he would take the life of any man who provoked him. He is at the head and front of any mischief. ”

- ↑ a b Alexandra Hasluck: Yagan, the Patriot . In: Early Days: Journal and Proceedings of the Royal Western Australian Historical Society (Inc.) V, VII, pp. 33-48.

- ↑ George Fletcher Moore: Diary of Ten Years Eventful Life of an Early Settler in Western Australia, and also a Descriptive Vocabulary of the Language of the Aborigines. M. Walbrook, London 1884. Facsimile edition: University of Western Australia Press, Nedlands, Western Australia 1978, ISBN 0-85564-137-1 .

- ↑ According to Moore, Heegan's gunshot wounds were so severe that parts of the brain leaked out. He would have had no chance of survival and would probably have died in the next few hours. It can therefore actually not be ruled out that Heegan's suffering should be ended with the headshot.

- ^ The Perth Gazette. July 13, 1833

- ^ A b Paul Turnbull: Outlawed Subjects: The Procurement and Scientific Uses of Australian Aboriginal Heads, approx. 1803-1835. In: Eighteenth-Century Life. 22, 1, pp. 156-171.

- ^ Robert Dale: Descriptive Account of the Panoramic View & c. of King George's Sound and the Adjacent Country. J. Cross & R. Havell, London 1834.

- ↑ a b Ken Colbung. Yagan: The Swan River "Settlement" . Australia Council for the Arts 1996

- ↑ a b c Cressida Fforde: Chapter 18: Yagan . In: Cressida Fforde, Jane Hubert & Paul Turnbull (eds.): The Dead and Their Possessions: Repatriation in Principle, Policy, and Practice Routledge, London 2002, ISBN 0-415-23385-2 , pp. 229-241.

- ^ A b Archaeological Geophysics: Yagan's Head. In: The St. Andrews Citizen , University of St Andrews , 2005.

- ↑ In English the quote is: “Because the Poms did the wrong thing they have to suffer. They have to learn too, to live with it as we did and that is how nature goes. "

- ↑ Paul Lampathakis: Hunt for Yagan narrows . In: The Sunday Times , March 6, 2005.

- ^ Press Cuts ( Memento of March 2, 2011 in the Internet Archive ). In: National Indigenous Times , Issue 97, January 26, 2006.

- ↑ A cremation would be in line with the traditional funeral rites of the Aborigines. One of the oldest Aboriginal burial sites is the at least 23,000 year old burial site of a young woman who was partially burned after her death. See also Blainey, p. 6.

- ^ Martin Philip: Yagan waits for final resting place . In: The West Australian , June 26, 2006.

- ↑ Yagan's head reburied in Swan Valley. (No longer available online.) The West Australian, July 10, 2010, archived from the original on September 16, 2012 ; Retrieved July 11, 2010 (English). Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Dean Alston: Alas Poor Yagan . The West Australian , September 6, 1997

- ↑ Her official title is "Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission"

- ^ Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission: Corunna v West Australian Newspapers (2001) EOC 93-146 . April 12, 2001.

- ↑ Federal Court of Australia: Bropho v Human Rights & Equal Opportunity Commission [2004] FCAFC February 16 , 2004.

- ↑ Melissa Kent: Yagan center of cover-up bid . The West Australian , November 24, 2005

- ^ Mary Durack: Courteous Savage: Yagan of the Swan River . Thomas Nelson (Australia) Limited, West Melbourne, Victoria 1964

- ^ Mary Durack: Yagan of the Bibbulmun . Thomas Nelson (Australia) Limited, West Melbourne, Victoria 1976, ISBN 0-17-001996-9 .

- ^ Sally Riley, Archie Weller: Confessions of a Headhunter. Scarlett Pictures, Surrey Hills, New South Wales 1999.

- ↑ Confessions of a Headhunter (2000). In: Australia's audiovisual heritage online .

- ^ John Mateer: Loanwords . Fremantle Arts Center Press, Fremantle, Western Australia 2002, ISBN 1-86368-359-3 .

- ^ P. Portman: Register of Australian Winter Cereal Cultivars. Hordeum vulgare (Barley) cv. Yagan . In: Australian Journal of Experimental Agriculture. Volume 29, 1989, No. 1, p. 143.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Yagan |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Egan, Eagan |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Noongar warriors |

| DATE OF BIRTH | around 1795 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Western Australia , Australia |

| DATE OF DEATH | July 11, 1833 |

| Place of death | Belhus, suburb of Perth , Australia |