Methylphenidate

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 11–52% |

| Protein binding | 30% |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Elimination half-life | 2–4 hours |

| Excretion | Urine |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.003.662 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

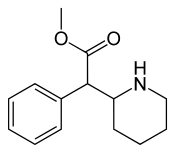

| Formula | C14H19NO2 |

| Molar mass | 233.306 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| Indicated for: Recreational uses:

Other uses: |

Contraindications:

|

| Side effects:

Atypical sensations:

Eye:

Skin: Urogenital and reproductive: Miscellaneous:

|

Methylphenidate (MPH) is a prescription stimulant commonly used to treat Attention-deficit disorder (ADD) and Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, or ADHD. It is also one of the primary drugs used to treat the daytime drowsiness symptoms of narcolepsy and chronic fatigue syndrome. Brand names of drugs that contain methylphenidate include Ritalin (Ritalina, Rilatine, Ritalin LA (Long Acting)), Attenta, Concerta (a sustained release capsule), Metadate, Methylin, Penid, and Rubifen. Focalin is a preparation containing only dextro-methylphenidate, rather than the usual racemic dextro- and levo-methylphenidate mixture of other formulations. A newer way of taking methylphenidate is by using a transdermal patch (under the brand name Daytrana), similar to those used for hormone replacement therapy and nicotine release.

History

Methylphenidate was patented in 1954 by the Ciba pharmaceutical company (one of the predecessors of Novartis) and was initially prescribed as a treatment for depression, chronic fatigue, and narcolepsy, among other ailments. Beginning in the 1960s, it was used to treat children with ADHD, known at the time as hyperactivity or minimal brain dysfunction (MBD). Today methylphenidate is the medication most commonly prescribed to treat ADHD around the world. According to most estimates [citation needed], more than 75 percent of methylphenidate prescriptions are written for children, with boys being about four times as likely to take methylphenidate as girls. Production and prescription of methylphenidate rose significantly in the 1990s, especially in the United States, as the ADHD diagnosis came to be better understood and more generally accepted within the medical and mental health communities.

Most brand-name Ritalin is produced in the United States, although methylphenidate is also produced in Mexico, Argentina and Pakistan by respective contract pharmaceutical manufacturers and is most commonly marketed under the brand name "Ritalin" for Novartis. In the United States, various generic forms of methylphenidate are also produced by several pharmaceutical companies (such as Methylin, etc.), and Ritalin is also sold in the United Kingdom, Germany, and other European countries (although in much lower volumes than in the United States). These generic versions of methylphenidate tend to outsell brand-name "Ritalin" four-to-one. In Belgium the product is sold under the name "Rilatine" for Novartis.

Another medicine is Concerta, a once-daily extended release form of methylphenidate, which was approved in April 2000. Studies have demonstrated that long-acting methylphenidate preparations such as Concerta are just as effective, if not more effective, than IR (instant release) formulas.[2][3][4][5] Time-release medications are also harder to misuse.

In April 2006, the FDA approved a transdermal patch for the treatment of ADHD, called Daytrana. The once-daily patch administers methylphenidate in doses of 10, 15, 20, or 30mg.[6] However, the patch must be applied several hours before the effect is desired, and the drug's effect remains for several hours after removal, making it necessary to remove the patch in the mid-to-late afternoon or else insomnia may result.

Pharmacology

Methylphenidate has binding affinity for both the dopamine transporter and norepinephrine transporter, with the D-isomer displaying a prominent affinity for the latter. Both the dextro- and levorotary isomers displayed receptor affinity for the serotonergic 5HT1A and 5HT2B subtypes, though direct binding to the serotonin transporter was not observed. [7]

The isomeric profiles and relative usefulness of dextro- and levo-methylphenidate is analogous to what is found in amphetamine, where dextro-amphetamine is considered to have a more beneficial effect than levo-amphetamine. Dextro-methylphenidate, the active enantiomer, is considered to provide the pharmacological effect of mental focus.[citation needed]

Effects

Methylphenidate is a central nervous system (CNS) stimulant.[8][9][10] It has a calming effect on humans who have ADHD, reducing impulsive behavior, and facilitates concentration on work and other tasks. Adults who have ADHD often report that methylphenidate increases their ability to focus on tasks and organize their lives.

Methylphenidate has been found to have a lower incidence of side effects than dextroamphetamine, a less commonly prescribed medication.[11] When prescribed at the correct dosage, methylphenidate is usually well tolerated by patients.[2]

The means by which methylphenidate helps people with ADHD are not well understood. Some researchers have theorized that ADHD is caused by a dopamine imbalance in the brains of those affected. Methylphenidate is a dopamine reuptake inhibitor, which means that it increases the level of the dopamine neurotransmitter in the brain by partially blocking the transporters that remove it from the synapses.[12] An alternate explanation which has been explored is that the methylphenidate affects the action of serotonin in the brain[13].

Side effects

Reported side effects include difficulty sleeping, stomach aches, headaches, lack of hunger (leading to weight loss) and dry mouth. Less common side effects include palpitations, high blood pressure and pulse changes. Ritalin at one time was used to treat depression, but is no longer used for that purpose because those going off the drug (a stimulant) sometimes experience a greater state of depression during the time of withdrawal[citation needed]. For these reasons, some doctors recommend patients taking the drug to take drug "holidays" in order to allow the body to recover and cope with the chronic presence of a stimulant in the system[citation needed].

Known or suspected risks to health

Researchers have also looked into the role of methylphenidate in affecting stature, with some studies finding slight decreases in height acceleration.[14] Other studies indicate height may normalize by adolescence.[15][16] In a 2005 study, only "minimal effects on growth in height and weight were observed" after 2 years of treatment. "No clinically significant effects on vital signs or laboratory test parameters were observed." [17]

A 2006 review assessing the safety of methylphenidate on the developing brain found that in animals with psychomotor impairments, structural and functional parameters of the dopamine system were improved with treatment [18]. This indicates that in subjects with ADHD, methylphenidate treatment may positively support brain development.

A 2003 study tested the effects of d-methylphenidate (Focalin), l-methylphenidate, and d, l-methylphenidate (Ritalin) on mice to search for any carcinogenic effects. The researchers found that all three compounds were non-genotoxic and non-clastogenic; d-MPH, d, l-MPH, and l-MPH did not cause mutations or chromosomal aberrations. They concluded that none of the compounds present a carcinogenic risk to humans.[19].

In February 2005, a team of researchers from The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center led by R.A. El-Zein announced that a study of 12 children indicated that methylphenidate may be carcinogenic. In the study, 12 children were given standard therapeutic doses of methylphenidate. At the conclusion of the 3-month study, all 12 children displayed significant treatment-induced chromosomal aberrations. The researchers indicated that their study was relatively small and their results needed to be reproduced in a bigger population for a definitive conclusion about the genotoxicity of methylphenidate to be drawn. [20]

In response to the El-Zein study published in 2005, a team of six scientists from the Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Psychotherapy and the Department of Toxicology, University of Würzburg, Würzburg, Germany began a more in-depth study. They sought to respond to the challenge noted above to attempt to replicate the results of El-Zein et al. in a larger study. Their paper was completed in 2006 and published in 2007 in Environmental Health Perspectives (EHP), the peer-reviewed journal of the United States' National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. This study used a larger cohort and a longer period of follow-up and included a small group of long-term users, but otherwise used what researchers believed to be an identical methodology to that used by El-Zein et al. (They note that El-Zein et al. published a short study report and did not publish detailed descriptions of methodology.) After follow-ups at six months, the researchers found no evidence that methylphenidate might cause cancer, stating "the concern regarding a potential increase in the risk of developing cancer later in life after long-term MPH treatment is not supported". [21] The full text of this study is published online and freely available to be read through PubMed.

The effects of long-term methylphenidate treatment on the developing brains of children with ADHD is unknown. Cocaine, methylphenidate and amphetamine have similar pharmacology. Although the safety profile of short-term methylphenidate therapy in clinical trials has been well established, repeated use of psychostimulants such as methylphenidate is less clear; but long-term therapy has been known to cause drug dependence, paranoia, schizophrenia, and behavioral sensitization.[22]

In the United States, methylphenidate is classified as a Schedule II controlled substance, the designation used for substances that have a recognized medical value but present a high potential for abuse because of their addictive potential. Internationally, methylphenidate is a Schedule II drug under the Convention on Psychotropic Substances.[23] Methylphenidate has been used illegally by students for whom the drug has not been prescribed, to assist with coursework and examinations.[24] The use of ADHD medication in children under the age of 6 has not been studied. ADHD symptoms include hyperactivity and difficulty holding still and following directions; these are also characteristics of a typical child under the age of 6. For this reason it may be more difficult to diagnose young children, and caution should be used with this age group.[25]

Risk of death

By early 2006 at least 19 cases had been reported of Cardiac arrest in children taking methylphenidate(New Scientist 18 Feb. 2006). In response the Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committee to the FDA on February 10, 2006 voted by a margin of eight to seven to recommend a "black-box" warning describing the cardiovascular risks "for children with underlying cardiovascular defects" of stimulant drugs used to treat attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder [26]. In response to this recommendation, on March 22, 2006. the FDA Pediatric Advisory Committee decided that the medications do not need "black box" warnings about their risks, noting that Template:PDFlink [27]

Delivery

Ritalin: 5 mg, 10 mg, and 20 mg tablets;

Ritalin SR: 20 mg tablets;

Ritalin LA: 10 mg, 20 mg, 30 mg, and 40 mg capsules;

Attenta: 10mg tablets;

Methylin: 5 mg, 10 mg, and 20 mg tablets;

Methylin ER: 10 mg and 20 mg tablets;

Metadate ER: 10 mg and 20 mg tablets;

Metadate CD: 10 mg, 20 mg, 30 mg, 40 mg, and 60 mg capsules;

Concerta: 18 mg, 27 mg, 36 mg, and 54 mg tablets;[28]

Equasym: 5 mg, 10 mg, and 20 mg tablets;

Rubifen: 5 mg, 10 mg, and 20 mg tablets;

Daytrana: 10 mg, 15 mg, 20 mg, and 30 mg patches

Criticism

Methylphenidate is frequently used in the treatment for ADHD, and as such criticism of methylphenidate is typically related to the controversy about ADHD.

Generally criticism of Methylphenidate revolves around the alleged or established side effects. Concerns about illicit use of the drug (when crushed and snorted, the effects of Methylphenidate are somewhat similar to cocaine)[29] and the ethics of giving Methylphenidate to children to reduce ADHD symptoms.

There have also been allegations that use of this medication can lead to a life of substance abuse, although a 2003 paper published in the official Journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics suggests the opposite, that in fact "stimulant therapy in childhood is associated with a reduction in the risk for subsequent drug and alcohol use disorders".[30] Another article in that same edition of Pediatrics indicated "no compelling evidence that stimulant treatment of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder leads to an increased risk for substance experimentation, use, dependence, or abuse by adulthood"[31]

See also

- Dexmethylphenidate (Focalin)

- Ethylphenidate

- Psychoactive drug

- Stimulant

- Amphetamine

- Methamphetamine

- Benzedrine

- Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder

- Controversy about ADHD

- Pemoline

References

- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 Oct 2023.

- ^ a b Steele, M., et al. (2006). "Template:PDFlink". Can J Clin Pharmacol. 2006 Winter;13(1):e50-62.

- ^ Pelham, W.E., et al. (2001). "Once-a-day Concerta methylphenidate versus three-times-daily methylphenidate in laboratory and natural settings". Pediatrics. 2001 Jun;107(6):E105.

- ^ Keating, G.M., McClellan, K., Jarvis, B. (2001). "Methylphenidate (OROS formulation)". CNS Drugs. 2001;15(6):495-500; discussion 501-3.

- ^ Hoare, P., et al. (2005). "Template:PDFlink". Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005 Sep;14(6):305-9.

- ^ Peck, P. (2006, 7 April). FDA Approves Daytrana Transdermal Patch for ADHD. MedPage today. Retrieved April 7, 2006, from http://www.medpagetoday.com/ProductAlert/Prescriptions/tb/3027.

- ^ Markowitz JS "et al." (2006). "A Comprehensive In Vitro Screening of d-, l-, and dl-threo-Methylphenidate: An Exploratory Study". "J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol". 2006 Dec;16(6):687-98.

- ^ Fone KC (2005). "Stimulants: use and abuse in the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder". Current opinion in pharmacology. 5 (1): 87–93. PMID 15661631.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Sharma RP (1990). "Pharmacological effects of methylphenidate on plasma homovanillic acid and growth hormone". Psychiatry research. 32 (1): 9–17. PMID 2190251.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Shults T (1981). "Pharmacokinetics and behavioral effects of methylphenidate in Thoroughbred horses". American journal of veterinary research. 42 (5): 722–6. PMID 7258793.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Barbaresi, W.J., et al. (2006). "Long-Term Stimulant Medication Treatment of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: Results from a Population-Based Study". J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2006 Feb;27(1):1-10.

- ^ Volkow N., et al. (1998). "Dopamine Transporter Occupancies in the Human Brain Induced by Therapeutic Doses of Oral Methylphenidate". Am J Psychiatry 155:1325-1331, October 1998.

- ^ Gainetdinov, Raul R. (2001). "Genetics of Childhood Disorders: XXIV. ADHD, Part 8: Hyperdopaminergic Mice as an Animal Model of ADHD". Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 40 (3): 380–382. Retrieved 2006-11-11.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Rao J.K., Julius J.R., Breen T.J., Blethen S.L. (1996). "Response to growth hormone in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: effects of methylphenidate and pemoline therapy". Pediatrics. 1998 Aug;102 (2 Pt 3):497-500.

- ^ Spencer, T.J., et al. (1996)."Growth deficits in ADHD children revisited: evidence for disorder-associated growth delays?". J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996 Nov;35(11):1460-9.

- ^ Klein R.G. & Mannuzza S. (1988). "Hyperactive boys almost grown up. III. Methylphenidate effects on ultimate height". Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988 Dec;45(12):1131-4.

- ^ Wilens, T., et al. (2005). ADHD treatment with once-daily OROS methylphenidate: final results from a long-term open-label study". J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005 Oct;44(10):1015-23.

- ^ Grund T., et al. "Influence of methylphenidate on brain development - an update of recent animal experiments", Behav Brain Funct. 2006 Jan 10;2:2.

- ^ Teo, S.K., et al. (2003). "D-Methylphenidate is non-genotoxic in vitro and in vivo assays". Mutat Res. 2003 May 9;537(1):67-79.

- ^ El-Zein R.A., et al. (2005). "Cytogenetic effects in children treated with methylphenidate". Cancer Lett. 2005 Dec 18;230(2):284-91.

- ^ Walitza, Susanne, et al. (2007). "Does Methylphenidate Cause a Cytogenetic Effect in Children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder?". Environmental Health Perspectives. 2007 June; 115(6): 936–940.

- ^ Dafny N (15). "The role of age, genotype, sex, and route of acute and chronic administration of methylphenidate: A review of its locomotor effects". Brain research bulletin. 68 (6): 393–405. PMID 16459193.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=and|year=/|date=mismatch (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Template:PDFlink 23rd edition. August 2003. International Narcotics Board, Vienna International Centre. Accessed 02 March 2006

- ^ Pittsburgh Tribune-Review. "More students abusing hyperactivity drugs".

- ^ Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

- ^ Minutes of the FDA Pediatric Advisory Committee, March 22, [2006]

- ^ Minutes of the FDA Pediatric Advisory Committee, March 22, [2006]. Template:PDFlink

- ^ Full Prescribing Information for Concerta. Template:PDFlink

- ^ Slate Is Ritalin "Chemically Similar" to Cocaine?

- ^ Wilens, T.E.., et al. (2003). "Does Stimulant Therapy of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Beget Later Substance Abuse? A Meta-analytic Review of the Literature". PEDIATRICS. 2003 Vol. 111 No. 1:pp. 179-185

- ^ Russell A. Barkley, PhD,et al. (2003). "Does the Treatment of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder With Stimulants Contribute to Drug Use/Abuse? A 13-Year Prospective Study". PEDIATRICS. 2003 Vol. 111 No. 1: pp. 97-109