MDMA

| Structural formula | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||||||||

| ( R ) shape (top) and ( S ) shape (bottom) | |||||||||||||

| General | |||||||||||||

| Surname | 3,4-methylenedioxy- N -methylamphetamine | ||||||||||||

| other names | |||||||||||||

| Molecular formula | C 11 H 15 NO 2 | ||||||||||||

| Brief description |

|

||||||||||||

| External identifiers / databases | |||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

| Drug information | |||||||||||||

| Drug class | |||||||||||||

| properties | |||||||||||||

| Molar mass | 193.25 g · mol -1 | ||||||||||||

| Melting point |

|

||||||||||||

| boiling point |

155 ° C (2.6 k Pa ) |

||||||||||||

| solubility |

22.97 mg ml −1 in water (hydrochloride) |

||||||||||||

| safety instructions | |||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

| Toxicological data | |||||||||||||

| As far as possible and customary, SI units are used. Unless otherwise noted, the data given apply to standard conditions . | |||||||||||||

MDMA represents the chiral chemical compound 3,4 M ethylene d ioxy- N - m ethyl a mphetamin . Structurally, it belongs to the group of methylenedioxyamphetamines and is particularly known as a party drug that is widely used worldwide .

In the 1980s, MDMA was synonymous with the drug ecstasy - also known as E for short - and it is so in the perception of many consumers and in media coverage to this day. In fact, since the 1990s, pills with the name "Ecstasy" have been increasingly traded that have little or no MDMA but also other ingredients, even though more than half of the "Ecstasy" pills, according to various studies, continue to be MDMA contain. Recently, both Molly and Emma have been understood synonymously with MDMA in powdered form by consumers and in reporting (especially in the USA), although these are also diluted with other substances or do not contain any MDMA at all.

Some drug users are therefore no longer consuming MDMA in pill form (as “ecstasy”) or powdered (as “molly”), but in the form of crystals, in the hope of being able to avoid the undesired stretching of the active ingredient.

history

The claim that became public in the early 1990s that Fritz Haber had manufactured MDMA in the course of his doctoral thesis could not be confirmed. The examination of the dissertation from 1891 did not reveal any relevant clues. The chemist Anton Köllisch first synthesized MDMA (then known as methylsafrylamine ) in the laboratory of the pharmaceutical company E. Merck as an intermediate in the synthesis of hydrastinine and its derivatives. On December 24, 1912, Merck applied for a patent for this, which was granted on May 16, 1914. It essentially describes a general synthesis route for various amphetamines with oxygen-bound substituents on the benzene ring. MDMA was an intermediate in the search for a hydrastinine analog. At the time, these were called "hemostatic agents" (hemostatic agents that contract the blood vessels). The Merck preparation methylhydrastinine resulted from MDMA as a synthesis intermediate . The assumption that MDMA was developed or sold as an appetite suppressant ( anorectic ) was not confirmed.

In 1927, the Merck chemist Max Oberlin probably carried out the first pharmacological tests on humans without trials. He stopped the research on it again, with the note that one should "keep an eye on" the substance. The term MDMA was first mentioned in 1937 as a description of the specific effect of amphetamine, which was discovered by chance . In 1952, the Merck chemist Albert van Schoor carried out toxicological experiments with flies and noted: “After 30 minutes 6 flies dead”. A scientific publication did not follow from this.

According to his own statements, the chemist Alexander Shulgin synthesized the substance himself for the first time in 1965 , after having experimented with the related substances MMDA and MDA from 1962 and researched their psychoactive potential through self-experiments. MDA was meanwhile in the 1960s in parts of the hippie culture in San Francisco known as the so-called "love drug" (or "hug drug"). It is unclear whether Shulgin himself tested the substance at this point in time, as is the point in time when exactly a person first consumed MDMA. From 1970 the US police seized the first MDMA consumption units. Shulgin became prominent in the history of MDMA when he published the first psychopharmacological study on MDMA together with US pharmacologist David Nichols in 1978.

MDMA was used by some psychotherapists in their practice in the years that followed until it was banned by the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) in July 1985. Since the DEA in 2001 the therapeutic use of MDMA, limited to the indication of post-traumatic stress disorder ( posttraumatic stress disorder ) allowed uses a small number of American psychotherapists during the therapy (exploration), but not as a drug, now back to it.

MDMA was fully marketable until the mid-1980s. Its use as a drug or recreational drug was first observed in some yuppie bars in Dallas , Texas, then spread to New York's gay dance scene, and finally, mixed with other substances, to rave clubs . At this time the American Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) became aware of MDMA. It banned the drug in the United States in 1985; a year later followed a worldwide ban by the World Health Organization ( WHO). In parallel with the growing popularity of rave culture, the spread of ecstasy / MDMA grew in the 1990s. During the Second Summer of Love in 1988, ecstasy / MDMA became popular in Europe as part of the British acid house movement and developed into the drug of the emerging rave culture. The news magazine Der Spiegel reported for the first time on June 22, 1987 about the new trend as follows:

“Above all, MDMA, which is very similar to the Central American plant extract mescaline, is“ becoming increasingly widespread in the drug scene ”, summarizes a report by the Federal Ministry of Health. This amphetamine derivative, already registered for a patent in 1914 by the Darmstadt pharmaceutical company Merck, has been subject to the provisions of the Narcotics Act since August 1, 1986. It is now being sold nationwide as "XTC" or "Exstasy", the current black market price per capsule: around 60 marks. "

Alongside cannabis , cocaine and amphetamine (including methamphetamine ) , MDMA has been one of the most widely used illegal drugs since the 1990s .

Terms used in illegal distribution

Ecstasy or XTC

Ecstasy , also known as XTC , is a term that was created around 1980 for so-called “party pills” that initially contained almost exclusively MDMA. Today ecstasy is in fact the collective name for a large number of phenylethylamines - in the perception of many consumers, however, in the "ideal case" it continues to be only for MDMA.

Ecstasy is usually produced in tablet or capsule form and is mixed with a carrier.

Ecstasy tablets are often referred to as "E" s , pills and parts in the scene . A market price of around five to ten euros is currently being achieved per piece, and production costs are less than one euro. The German Monitoring Center for Drugs and Drug Addiction determined a slightly higher market price of EUR 8.50 on average for 2013, after EUR 8 in the previous year. The EMCDDA measured prices between 4 and 17 euros per pill across Europe with an accumulation of between 5 and 9 euros.

In practice, some users consume a pill that is offered to them as “ecstasy” and possibly actually contains MDMA, and then associate it with a corresponding experience, with the next pill containing a completely different active ingredient or a different concentration and therefore completely different Reactions. That is why in some circles the use of the term “ecstasy” or the pills offered is downright frowned upon because it is too unspecific if MDMA is to be consumed. Some people use a drug test like the Marquis reaction to check whether a pill offered them contain MDMA at least can . In fact, this test can only be used to conclude that it definitely does not contain MDMA in the event of a negative result . A positive reaction, on the other hand, does not guarantee that it does not contain other ingredients. The concentration of the active ingredient within the pill cannot be determined with this test either. However, this is another danger of using “ecstasy” (see section “Dangers”).

The duration of action is usually four to six hours, provided that it actually contains MDMA. In 2012, active ingredient contents of 1 mg up to - for most consumers overdosed - 216 mg per pill were determined in Germany, as well as a median of 83 mg. The active ingredient content rose continuously from 50 mg in 2009 (58 mg in 2010; 73 mg in 2011).

Throughout Europe, the EMCDDA 2012 measured active ingredient levels between 43 and 113 mg per pill with an accumulation between 64 and 90 mg, whereby in 2012 4.3 million pills were seized across Europe (excluding Turkey).

Most tablets have “trademarks” pressed into them, such as birds, hearts, dolphins, butterflies or (especially car) company emblems. Since they can easily be copied, these identification marks do not give any reliable indication of the effect or the ingredients. Ecstasy tablets with not clearly defined contents have repeatedly resulted in deaths (see section Dangers ).

Other substances that are often found in ecstasy in addition to or instead of MDMA are, for example: amphetamine , N -methylamphetamine , 4-methoxyamphetamine (PMA), meta- chlorophenylpiperazine (mCPP, a piperazine derivative ), para- methoxy- N -methylamphetamine (PMMA) ), 3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDA), 3,4-methylenedioxy-N-methylcathinone (MDMC), 3,4-methylenedioxy-N-ethylamphetamine (MDEA), 2-amino-1- (3,4-methylenedioxyphenyl) butane (BDB), 2-methylamino-1- (3,4-methylenedioxyphenyl) butane (MBDB), 4-bromo-2,5-dimethoxyphenylethylamine (2C-B) etc.

The proportion of samples that only contain the active ingredient MDMA has demonstrably declined significantly in Switzerland and Austria - where so-called drug checking is legally carried out in the vicinity of public parties. Pill warnings have to be issued more and more frequently based on drug checking results . The percentage of tablets bought as "ecstasy" that did not contain any psychotropic substances other than MDMA, MDE or MDA was 63 percent in Austria in 2008, roughly the same as in the previous year, but significantly lower than in previous years (70 to 90%) ).

In the Federal Republic of Germany, however, the situation is different according to official information: According to investigations by the Federal Criminal Police Office , around 97% of the monopreparations examined contained MDMA in 2008, which is still the case in 2012. The 2013 drug report even states: “After reports were made about an improved range of ecstasy tablets with a higher MDMA content in the last reporting year, this trend continued in 2012.” The image of ecstasy tablets had changed in the wake of “the already in The noticeable quality improvement that occurred last year has been significantly improved. "

“The skepticism of recent years, caused by tablets with other, undesirable active ingredients (“ bad pills ”), seems to be gradually disappearing due to positive consumption experiences. All trend scouts unanimously report a consistently high availability "

In the 2014 annual report, the DBDD presented more precise figures for the previous year: According to this, 99.2 percent of all pills examined contained only one preparation (2012: 94.9%). Of these monopreparations, 92.6% were MDMA. According to this, around 9 out of 10 pills offered as “ecstasy” would actually be pure “MDMA pills”. However, 6.6% of the pills with only one active ingredient contained only amphetamine (Speed), as well as 0.7% m-CPP and less than 0.1% MDA or MDE each. Whether these figures, which only refer to the pills seized by the authorities, are really representative, however, can be doubted, given the fact that in Austria and Switzerland, where data from voluntary "drug checking" are available, significantly more " Ecstasy “pills contain other active ingredients than MDMA (see above).

A clear differentiation from ecstasy or MDMA is so-called "bio-ecstasy" or herbal ecstasy , which mostly consists of a mixture of guaraná , caffeine , ephedra and other substances and is a legally available drug (in Germany only limited; ephedra is For example, a prescription has been required for some years), with a slightly stimulating effect, comparable to that of energy drinks . Another clear distinction from MDMA is the so-called liquid ecstasy , which is also known as fantasy and consists of GHB ( gammahydroxybutyric acid ). This substance is mostly traded in liquid form and differs greatly from MDMA both in its effect and in its chemical composition.

Molly

Recently, MDMA has also been associated with the term Molly, especially in the USA . The trend was initiated in particular by artists such as Miley Cyrus , Kanye West or Madonna , who made the term known through public statements or even in song lyrics. Molly is usually an illegally sold powder, which is sometimes even advertised as a “pure form of MDMA”. The latter happens in particular to distinguish it from ecstasy - which has not only had to contain MDMA for decades. In fact, according to at least initial samples, the products sold as Molly contain MDMA even more rarely than is the case with ecstasy.

According to the US drug enforcement agency DEA , Molly products seized in New York State between around 2009 and 2013 contained MDMA in only 13 percent of cases, and in these cases often other substances such as methylone , MDPV , 4-MEC , 4- MMC , Pentedron or MePPP .

MDMA crystals

The consumption of pure MDMA in crystalline form (scene names including M or Emma , including pure MD , previously also Cadillac ) is enjoying increasing popularity among drug users . The advantage is that in addition to the marquis test , which can in principle also be used for pills, the appearance and the (non-existent) smell of the substance can also provide at least further indications of authenticity with appropriate experience. In addition, the dosage can be more precise.

MDMA crystals are often "dipped" with a moistened finger or dissolved in drinks and drunk. According to the German Observatory for Drugs and Drug Addiction, crystals tend to be more privately "traded" compared to pills. The spread of MDMA crystals is reported from seven out of eight scenes from the field of electronic music. In general, crystals are associated with “an idea of high quality.” The actual quality is described as consistently good.

According to a survey for the Zeit-Online-Drug Report in autumn 2013, which was carried out as part of the Global Drug Survey , the consumers surveyed allegedly paid an average of 33 euros for 1 gram of pure MDMA. However, the German Monitoring Center for Drugs and Drug Addiction has determined a price of an average of 50 euros per gram for 2012, which is roughly the same as in 2011.

Not to be confused are MDMA crystals specifically with the drug crystal , however, the consumer enters a certain risk for existing voice or comprehension problems accidentally Crystal to obtain, when in respective circuits according to MDMA-crystals required.

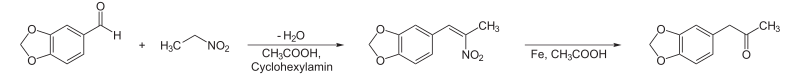

Chemistry, isomerism and synthesis

There are two enantiomers , the ( R ) form and the mirror image ( S ) form of the active ingredient MDMA. The free base MDMA is an oil and contains the functional group of a secondary amine R 2 NH. The free base forms a crystalline hydrochloride R 2 NH · HCl with hydrochloric acid . Piperonal is usually used as the raw material for the synthesis of MDMA . A possible synthetic route is described in PIHKAL : Piperonal is reacted with nitroethane in a condensation reaction ( Henry reaction ) to give 1- (3,4-methylenedioxyphenyl) -2-nitropropene. This is hydrogenated (using electrolytic iron and acetic acid) to piperonyl methyl ketone. The conversion of this compound with methylamine and simultaneous hydrogenation (by means of amalgamated aluminum and water) in one work step results in the end product MDMA. If, on the other hand, 3,4-methylenedioxyphenylpropan-2-one is reacted with methylamine and sodium cyanoborohydride in the last synthesis step, this leads to the formation of MDA .

There are several quantitative detection reactions :

- Chromotropic acid reaction

- Marquis reaction

- Content with perchloric acid in glacial acetic acid against crystal violet .

Pharmacological properties

Pharmacodynamics

MDMA acts in the central nervous system as a releaser of the endogenous monoamine neurotransmitters serotonin and noradrenaline , and with a somewhat weaker effect also dopamine , which leads to an unusually high level of these messenger substances in the brain. These transmitters have a decisive influence on people's moods. For details of the release effect, see also the pharmacology of amphetamine . Both enantiomers (dextro / levo MDMA) contribute in slightly different ways to the characteristic effect of MDMA.

MDMA has a special position among the “essential amphetamines”: In the case of N -methylation, these are generally much more effective per milligram (see amphetamine vs. methamphetamine). In contrast, MDA is felt to be “harder” on the body than MDMA. According to some authors, because of this uniqueness, MDMA should not actually be counted among the classic amphetamines, but should be viewed as a separate substance.

Psychological effect

Empathogenic effect

According to reports from consumers, the use of MDMA lifts mood ( euphoria ) and is intended to increase the tendency to social interaction ( empathogenic effect) as well as the perception of one's own feelings ( entactogenic effect). Possibly “ Set & Setting ” applies - afterwards, your own “brought” mood or the atmosphere of the environment would color the subjective experience of the MDMA effect and both pleasant feelings and a bad mood could be intensified.

Social perception

According to a study (2010) in which social behavior was measured under the influence of MDMA, there was a reduced perception of threatening facial expressions. The study's authors concluded that by the drug social approach - was promoted and not social empathy (- here by hiding risks empathy ). The results were confirmed by another study in which MDMA decreased the perception of simulated social rejection. Two further studies showed that MDMA on the one hand hindered the perception of negative feelings based on fearful, angry, hostile and sad faces, and on the other hand increased the ability to perceive positive feelings, with one study also increasing explicit and implicit emotional empathy and - in men - increased measured prosocial behavior.

Psychological complications

The most frequently reported acute complications are panic attacks - especially at the beginning of the action - and intoxication. Individual cases of hallucinations and persistent disorders according to the category of persistent perception disorder after hallucinogen use ( Hallucinogen Persisting Perception Disorder , HPPD) have been described since the 1990s and have recently become the subject of research. Psychotic effects lasting for weeks and months , in addition to hallucinations, panic attacks and depersonalization , have been described, several times even after a single consumption in the usual dose.

A possible consequence of MDMA consumption can also be increased aggressiveness , both during the immediate effect and after four days, but no longer after seven days. Both effects, acute effect and aftereffect after four days, were attributed to the known disorders of the serotonin systems.

Physical effect

The feeling of hunger, thirst and pain are reduced. There is an increase in pulse ( tachycardia ) and blood pressure ( arterial hypertension ), hyperthermia , whereby the body temperature can rise to 42 ° C, possibly favored by excessive physical exertion (dancing) and insufficient fluid intake. MDMA increases the breathing rate ( tachypnea ), the pupils are dilated ( mydriasis ) and the mouth becomes dry . In addition, the urge to move is increased, especially in the area of music. Many users also report an increased physical sensitivity, so that touches are perceived both actively and passively as above average, which is where MDMA is called a "cuddle drug".

unwanted effects

Unwanted effects ( side effects ) are also expressed in erectile dysfunction and orgasm disorders, in the weakening of the sense of taste and in a tickling sensation under the skin, which, however, is perceived as pleasant by many consumers. Particularly with overdoses or regular consumption, further undesirable consequences can occur: muscle cramps (e.g. the need to stretch the spine extremely straight), especially in the masticatory muscles ( trismus , bruxism ), nystagmus (muscle twitching, eye tremors), increased reflexes , nausea , clouding of consciousness , phases of depression (especially after the effects have wore off), internal cold (hypothermia), severe circulatory disorders , profuse sweating. People with heart failure , high blood pressure , diabetes mellitus , epilepsy and glaucoma are particularly prone to the effects . Isolated deaths after MDMA consumption are known (see section Dangers ), but it is not clear what amounts of MDMA were consumed within the previous 2-3 days and what the precise medical disposition of the cases was (source: Pathologie UK / Wales). The combination with alcohol or other drugs ( polyintoxication ) and dehydration due to insufficient fluid intake and overheating are considered to be special risk factors.

Most consumers experience a so-called come-down (also known as a "celebration depression" ) after the trip , which can last for several days. This is mainly due to general exhaustion and acute depletion of the serotonin stores in the brain. The symptoms are depressed mood , tiredness, listlessness and, less often, slight nausea. Sometimes this condition only sets in two to three days after consumption (so-called midweek blues ).

Elevated cortisol levels

In a review from 2014, various studies were cited that show that MDMA consumption leads to a marked increase in the release of the stress hormone cortisol . In a study design with clubbers, acutely increased cortisol values of up to 800% compared to the abstinent club-goers control group were measured in saliva samples, which, however, were reduced to almost the initial values after 72 hours:

- Cortisol levels of MDMA users: 0 h: 0.28 ± 0.29 µg / dl; 2.5 h: 2.19 ± 1.15 µg / dl; 72 h: 0.36 ± 0.46 µg / dl

- Cortisol values of the abstinent control group: 0 h: 0.21 ± 0.14 µg / dl; 2.5 h: 0.36 ± 0.41 µg / dl; 72 h: 0.24 ± 0.23 µg / dl

The effect of cortisol is both acute and - even in the case of later abstinence - in hair analyzes of consumers of legal and illegal psychoactive substances still detectable after three months. This effect was most pronounced in the group of heavy users who consumed MDMA more than five times in the measured three months (55.0 ± 80.1 pg / mg - cortisol in the hair analysis). The group of users who consumed MDMA moderately (less than four times in the measured three months) and the control group who were MDMA-abstinent showed only non-significant differences: moderate MDMA users (19.4 ± 16.0 pg / mg ; p = 0.015) vs. non-MDMA users (13.8 ± 6.1 pg / mg; p = 0.001).

"Recent Ecstasy / MDMA users who had taken the drug on five or more occasions during the past 3-months, demonstrated an almost 4-fold increase in hair cortisol levels compared to non-user controls, and an almost 3-fold increase compared to light Ecstasy / MDMA users. Lighter recent Ecstasy / MDMA users, who had taken the drug on less than 4 occasions in the past 3-months, showed group mean cortisol level slightly higher than controls, although the difference was not significant. "

The authors of the review (2014) conclude that the increased cortisol levels may be responsible for the negative MDMA effects:

"We conclude that ecstasy / MDMA increases cortisol levels acutely and subchronically and that changes in the HPA axis may explain why recreational ecstasy / MDMA users show various aspects of neuropsychobiological stress."

hazards

General and deaths

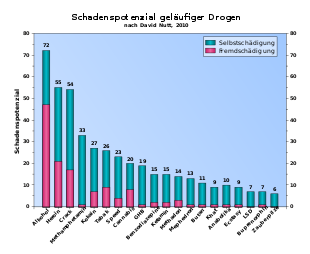

In many studies, MDMA is regularly classified as less harmful compared to drugs such as alcohol or sometimes even cannabis . For example, in a study published in March 2007 by a research team led by David Nutt in the journal The Lancet , MDMA came 17th out of the 20 substances compared, with alcohol and heroin being among the most dangerous drugs ( see drug: Classification according to potential harm ).

The 2013 Drugs Report from the European Monitoring Center for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) states:

“Symptoms associated with the use of this substance include acute hypothermia and psychological problems. Ecstasy-related deaths are rare. "

In Germany, for example, two deaths were counted in 2010 that were directly related to the sole consumption of “ecstasy”, and four further deaths involved “ecstasy” in combination with other drugs. In 2013, three deaths directly related to “amphetamine derivatives” were counted, although MDMA was not reported separately; in 2014 the corresponding number was three deaths, as in the previous year, six deaths in 2015, two deaths in 2016 and four deaths in 2017.

Dependency potential

MDMA has a certain potential for psychological dependence . However, in contrast to alcohol , cannabis , cocaine or opiates, in such cases there is only extremely seldom daily consumption of the drug, which can be linked to the spectrum of activity of the drug. More often, addiction is directly related to the usual setting in which the drug is taken - e.g. B. Technoparty environments - for example, when the weekends start on Thursdays and only end on Mondays and the person “drops” or “loses” themselves in the party atmosphere during this time.

With regular weekly consumption, the consumer often only “vegetates” over the week, doing his job and only blossoms again on the weekend with MDMA consumption. The time between consumption processes is characterized by listlessness, listlessness and often also depressive phases. As a rule, other drugs are also consumed, especially amphetamines, cannabis and alcohol. This rhythm, in which only the weekends are considered worth living in, is perceived by experts as the real danger of psychological dependence.

In the course of any kind of addiction, the dose is usually not increased, as this does not increase the intoxication; however, the undesirable side effects (muscle tension, irritability, jaw pain, headache and pain in the limbs, etc.) increase. Within the "scene", a break of at least 4–6 weeks between the individual consumption processes is recommended and is also observed by some regular users in order to be able to experience the full effect again.

Impurities

Many users assume that they are consuming pure MDMA when they take “ecstasy” pills or Molly . However, this is not always the case. One of the health hazards of MDMA use is the inadvertent ingestion of a fluctuating amount of unknown diluents or entirely different drugs sold as "ecstasy" or molly .

Mixed consumption and overdose

Overdosing with MDMA or mixed consumption with other drugs, particularly dangerous with methamphetamine, can in very rare cases lead to acute heart failure, not only in previously damaged, but also in healthy people, as MDMA (like most amphetamine derivatives) is a calcium antagonist (calcium channel blocker) is. This means that MDMA is a substance that inhibits the flow of calcium into the cells and thus disrupts the electromechanical coupling in the cell system. This leads to a reduction in the tone (state of tension) of the vascular muscles and the contractility (ability to contract) of the heart muscle.

Comparatively widespread - although risky - is mixed consumption with alcohol , according to a non-representative survey in more than half of the cases. This puts more strain on the liver and kidneys and dries out the body further. This also makes it easier for heat build-up and dangerous overheating to occur. In addition, the negative effects of “coming down” through mixed consumption with alcohol are further intensified, while the clear and entactogenic effects are reduced.

In particular, if MDMA is not consumed in crystalline form, but in pill form, there is a risk of overdosing with the negative reactions described below, since the amount of the active ingredient is generally not known with certainty unless a chemical analysis of a pill is carried out. In practice, the concentration is often 50–150 mg per tablet, provided that it actually contains MDMA (see above). In practice, however, the consumer hardly has a chance to correctly dose the amount of 1.3 (for women) to 1.5 mg (for men) MDMA per kg of body weight recommended in certain circles, provided that he is consuming a pill.

On the question of which overdose leads to death with a certain probability, there are different statements, ranging from 5 to 20 times the "regular dose", which in turn depends on the weight and condition of the consumer. For example, two cases from Berlin are documented in which a 10-fold dose was allegedly administered, although it is not publicly known what in this case was regarded as a “single dose”. In 2013, a 15-year-old girl in the UK died after consuming 500 mg of MDMA.

Life-threatening acute side effects

The greatest acute danger when consuming it is overheating, as MDMA has a dehydrating effect and increases temperature. Intense dancing increases the effect of overheating, and the consumer does not perceive the warning signals of the body correctly or at least in a weakened manner. Body temperature can rise to a dangerous 40 to 42 ° C, which in the worst case scenario can lead to organ failure and consequently to coma or even death. In theory, this can be counteracted comparatively easily by drinking regularly and taking breaks. However, since the feeling of thirst is greatly reduced or completely eliminated and there is a certain urge to move (see above "Physical effect"), this is often not done or done incorrectly by inexperienced users. In turn, consuming too much water can lead to hyperhydration . As a result, fatal cases of MDMA use have now been observed in both the US and Europe.

MDMA can cause an acute lowering of the sodium level in the blood (“ecstasy-induced hyponatremia ”). This rare but dangerous side effect can cause nausea, confusion, or an epileptic fit . In patients with this symptom, one in five cases is fatal. The mechanism of this side effect is not fully understood, but is believed to be triggered by MDMA itself. The side effect is aggravated by the female hormone estrogen , so the effect is more common in women. MDMA-induced hyponatremia is treated in mild cases by administering diuretics or limiting fluid intake; in severe cases, the patient is given an isotonic saline solution to restore the electrolyte balance.

In 2009 it was also shown that even abstinent former users have an increased risk of sleep apnea syndrome .

Neurotoxicity and long-term damage

The risk of cognitive deficits and memory deficits that MDMA users may expose themselves to is the subject of ongoing research. There are studies that consider a connection between consumption and corresponding deficits as proven in some areas, for example two large-scale longitudinal studies in the format of prospective cohort studies in Amsterdam (2007) and Cologne (2013). The relevance of these two studies is highlighted in a systematic review article from 2013 with a detailed description. The prospective longitudinal study by Halpern et al. (2011), however, could not determine any significant negative cognitive effects that can be traced back to MDMA consumption. Hermle et al. (2018) take into account the contradicting results of the prospective longitudinal studies and state in their review:

"Subtle disturbances in everyday memory are the most consistent current research findings that have been demonstrated in chronic ecstasy users."

In a meta-study published in 2009, a number of studies examining the neurotoxic effects of MDMA consumption were evaluated. On the one hand, the authors came to the conclusion that only a small proportion of the papers were of sufficient methodological quality. On the other hand, the high-quality studies mostly show neurotoxic consequences, whereby the clinical significance can fluctuate in each individual case, but on average the deficits are “probably relatively small”. The authors of the Dutch longitudinal study (see above) also speak of the fact that despite measured deficits in drug users, their performance is “still within the normal range” and the immediate clinical relevance is “limited” - although long-term consequences cannot be ruled out. In another systematic review from 2013, the following neurotoxic damage was listed: According to this, MDMA damages serotonergic nerve endings ( axon terminals ) in the striatum , hippocampus and prefrontal cortex . In rodents , non-human primates , and humans, such damage persists for at least two years. Evidence has been shown that MDMA reduces the number of GABAergic interneurons in the hippocampus. The neurotoxic damage was assigned to the deviant behavior of MDMA users - even during their periods of abstinence - such as decreased performance in terms of memory, attention, behavioral control and impulse control ( executive functions ). A comprehensive meta-analysis from 2016 on the basis of 39 individual studies found a small effect of MDMA on executive functions , which was considered to correspond to the neurotoxic effects in serotonergic nervous systems:

“The results from this meta-analysis demonstrate EF deficits in current ecstasy users. However, the size of this overall effect was small. "

“The results of this meta-analysis show EF deficits among current ecstasy users. The strength of the overall effect, however, was small. "

It could also not be ruled out that z. B. Alcohol or other drugs were responsible for the deficits in executive functions:

"As such, we cannot rule out the possibility that alcohol and other drugs may also contribute to deficits in executive functioning."

"We cannot therefore rule out that alcohol and other drugs can also contribute to deficits in executive functions."

According to Hermle et al. (2018), according to the current state of knowledge, long-term damage to the central serotonergic system is likely, at least in heavy users. It is known from animal experiments that chronic administration of high doses of MDMA leads to pathological changes in serotonin neurons. According to a study from 2001, non- metabolized MDMA does not appear to be cell-destroying. Several studies in people with various imaging modalities showed long-term disorders of the serotonin systems.

The degenerative effect on brain tissue can be caused by several parallel mechanisms. For example, MDMA breakdown products (by opening the methylene bridge ) can have cell-toxic properties. Furthermore, the uptake of dopamine in serotonin cells can lead to an incorrect metabolism of dopamine, which leads to the formation of the cell-toxic 6-hydroxydopamine. Experiments with rats also suggest that the hyperthermic effect of MDMA sometimes greatly increases the neurotoxic damage. The same also applies to an increased room temperature, as it is for. B. can be found in discos and clubs.

Studies with mice and rats showed that tetrahydrocannabinol , as well as the artificial cannabinoid CP 55,940, completely prevent the hyperthermal effect of MDMA. The resulting hypothermia reduces neurotoxic damage. However, a double-blind, placebo-controlled study in humans showed the opposite effect. Although the peak of the MDMA-related temperature increase due to the addition of cannabis was delayed by about 45 minutes, it was the same. A clear reinforcement effect from cannabis was given by the fact that the MDMA-related maximum temperature lasted longer than 2.5 hours (end of the measurements), while without the addition of cannabis it had already decreased after 45 minutes and after a further 2.5 hours had completely returned to the pre-MDMA level.

Several studies focusing specifically on memory performance revealed statistically significant deficits in MDMA users in all types of memory and depending on the extent of consumption. The impairments generally correlate with the duration and frequency of MDMA use, but not only heavy users but also relatively moderate occasional users can be affected.

Interactions with drugs and psychotropic substances

Certain drug interactions with MDMA pose a particularly high health risk. In particular, some antivirals such as the HIV protease inhibitor ritonavir or the reverse transcriptase inhibitor delavirdine lead to a sharp increase in the MDMA plasma level, which, in addition to prolonged intoxication, can cause life-threatening intoxication.

The pain reliever tramadol (opioid analgesics) also affects the serotonin and norepinephrine levels. With timed consumption of a corresponding drug and MDMA, the effect of both MDMA and the drug can be intensified, which can also be life-threatening.

There is a particular risk in the combination with MAO inhibitors , which are contained in drugs such as antidepressants ( moclobemide ) and dopaminergics for Parkinson's disease ( selegiline ) as well as in the psychoactive substance harmalin (component of the hallucinogenic drug ayahuasca ). Since MAO inhibitors increase the effect of additional triggers of serotonin , dopamine and noradrenaline , including MDMA, to a considerable and unpredictable degree, there is an incalculable risk here, especially in combination with ayahuasca due to its MAO inhibitor harmaline. Typical consequences of the combination are symptoms of serotonin syndrome , which can lead to death if the control of the respiratory muscles is disrupted. Since some MAOIs last for days, a two week period is required when they are discontinued before they can be used.

distribution

According to the German Observatory for Drugs and Drug Addiction, MDMA is one of the most popular “party drugs”, especially “in techno / house environments”. In the electronic dance scene, MDMA is said to be the second most widely consumed illegal substance, behind speed .

The European Drugs Report 2015 refers to a partial analysis of the Global Drug Survey on the spread of drugs , a non-representative online survey, according to which among 25,790 people between the ages of 15 and 34 in ten European countries who regularly take part in “club events” , there is a 12-month prevalence for MDMA of 37%. Even if this number is not representative, it is well ahead of most of the other values measured in the same analysis for other drugs ( cannabis 55%, cocaine 22%, amphetamines 19%, ketamine 11%, mephedrone 3%, synthetic cannabinoids 3 %, GHB 2%).

According to a survey of “young partygoers” that was carried out in various German cities from 2013 onwards, MDMA is even ahead of speed (51.1%) with a 12-month prevalence of 52.0%, but significantly behind cannabis (75, 1 %). 30.2% of the respondents stated that they had consumed MDMA within the last 30 days.

The 2014 report by the German Monitoring Center for Drugs and Drug Addiction also states:

“The popularity of ecstasy or MDMA is still limited to the scenes from the area of“ electronic dance music ”. There was an increase in the number of consumers there in 2013. The trend scouts assume that around half of all members of the scene have taken ecstasy or MDMA at least a few times in the past year; the availability is rated as “excellent”. Outside of these environments, there was only a slight increase in the punk rock scene as part of the establishment of parties with electronic music. The supply and prevalence of ecstasy tablets are still higher than those of crystalline MDMA. Ecstasy tablets with a particularly high content of active ingredients (up to 200 mg) have increasingly led to the involuntary ingestion of large amounts of MDMA, which has led to a noticeable increase in the occurrence of undesirable side effects. "

The European Monitoring Center for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) also claims to have observed tendencies for a “revival” of interest in MDMA, which is said to be due to the easier availability of the active ingredient. According to the 2013 Drug Report: "Recently, ecstasy manufacturers seem to have found more efficient ways to get MDMA, which is reflected in the contents of the tablets."

According to estimates by the EMCDDA, around 1.8 million young adults consumed “ecstasy” (MDMA) throughout Europe in 2012 - within the past year. With a 12-month prevalence of ecstasy use among young adults of just under 3 percent, MDMA appears to be the most popular in the UK in 2012 , followed by the Czech Republic and Spain (between 1 and 2 percent). The last current value is available for Germany with a prevalence of around 1 percent for the years 2008/2009. Slightly above average values of> 1% were also measured in the Netherlands , but the last available data is from 2003/2004.

According to EMCDDA, Belgium and the Netherlands as well as Poland and the Baltic countries are known as important production sites, but laboratories have also been discovered in Bulgaria, Germany and Hungary.

According to wastewater studies, MDMA is verifiably mainly consumed on weekends in various major European cities. Among the 42 cities examined, Amsterdam was the city with the highest MDMA consumption, followed by Utrecht and Antwerp. In Germany, only Dortmund, Dresden and Dülmen took part in the study, with a significant prevalence measured only in Dortmund, which, however, is well below the consumption in most of the other cities in Europe examined.

Use in medicine and psychotherapy

Like LSD and psilocybin , MDMA was used by psychiatrists for treatment purposes before it was banned (see “History” section). With the threat of production, transfer and possession being punished, research into MDMA with regard to medical use - with the exception of special permits - became impossible in most countries, so that promising but limited knowledge is available about the psychiatric potential of MDMA.

However, mainly in Switzerland , some researchers repeatedly receive special permits for clinical studies with MDMA, especially when it comes to the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorders . MDMA may be therapeutically indicated. a. also with anxiety neuroses, depression, character neuroses or obsessional neuroses.

Psychotherapy with MDMA is not without its dangers. They are less due to the substance itself than to improper use by therapists. As far as the possibility of abuse of power in psychotherapy can never be ruled out even without psychoactive substances, it is significantly increased by the use of MDMA. As experiences of therapy clients show, it can happen that the therapist takes on a guru role, especially if the treatment process is esoterically charged and takes place in illegality. But even under professional medical conditions, the use of drugs in psychotherapy is almost unanimously rejected. In general, the prevailing opinion in modern medicine is that a patient should express himself in a self-determined manner during therapy. A "helping out" with psychoactive substances is largely rejected by experts. Accepting the risk of psychological harm to the patient is considered unacceptable.

Legalization Debate

In contrast to cannabis, there is virtually no noticeable public debate about possible legalization of MDMA. If at all, the corresponding demands mostly relate to a possible use in psychotherapy. A corresponding petition to the German Bundestag was unsuccessful.

In 2015 the youth organization of the Democrats 66 party launched a signature campaign in the Netherlands to decriminalize MDMA.

Legal position

Germany

MDMA was included in Appendix I of the German Narcotics Act with effect from August 1, 1986 with the Second Amendment to the Narcotics Act . Since then, MDMA is neither marketable nor prescribable in Germany. This also means that the legislator has classified the medical benefit-risk assessment as negative for MDMA and is no longer an option for legal drug trade.

The inclusion in the Narcotics Act (BtMG) happened in accordance with international agreements. Herbert Rusche , a former member of the Bundestag for the Greens, submitted the following request to the federal government: “1. What profound findings prompted the federal government to classify MDMA under Appendix 1 of the BtMG? " The response from the responsible ministry was: " MDMA is a mescaline-amphetamine analogue that is one of the so-called designer drugs. MDMA was included in Appendix 1 of the 1971 Convention on Psychotropic Substances by the unanimous decision of the Narcotics Commission of the UN Economic and Social Council on February 11, 1986. For the FRG this resulted in the obligation to control MDMA as an addictive substance in the same way. The federal government has fulfilled this obligation by classifying MDMA in Appendix 1 of the BtMG. "

Since the German Narcotics Act essentially relates to the chemical ingredients of intoxicants, modifications of the active substances were often marketed commercially. They were considered legal until a revision of the Narcotics Act had taken place. This phenomenon in turn ensured that a whole series of new substances were included in the Narcotics Act every year. That is why the New Psychoactive Substances Act was introduced in 2016 .

See also Narcotics Act (Switzerland) and Narcotics Act (Austria)

United States

The American biochemist Alexander Shulgin was active in the research of phenethylamines in the 1960s . His interest in phenethylamines was in psychotomimetics or psychedelics such as mescaline , which could initiate radical changes in perception. In 1977 he introduced MDMA to Leo Zeff, a psychologist friend of his. Zeff then used MDMA in low doses as an aid in his counseling sessions and made it popular with psychologists and therapists around the world.

The drug was not known to the general public at the time. The psychologists who were new to MDMA and had good experiences feared that the American government would treat MDMA like LSD and ban it if it were to become popular as a drug. They treated their research results very discreetly, so that MDMA was only very slowly known as a drug. It wasn't until the early 1980s that it became known. At that time, the drug was still legal. In the USA, MDMA could be bought as ecstasy in bars and pharmacies . The rapid spread of drug use was the reason MDMA was eventually banned in the US. In 1985, the US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) was sued by consumers for wanting to ban ecstasy. This dispute was partly responsible for the drug's great popularity and spread. The US Congress passed a law that allowed the DEA to temporarily ban almost any drug that it expected to pose a health risk. MDMA became illegal in the United States on July 1, 1985. Psychotherapists, who expected the substance to be of great therapeutic benefit, wanted to ensure that MDMA could at least be used as a drug for psychotherapy and that research into it could continue. The DEA ignored these research results and permanently classified MDMA in the strictest category (Schedule 1) for drugs. It is currently practically the same as heroin and cocaine.

Great Britain

In the UK, entactogenic amphetamines such as MDA, MDEA and the MDMA have been illegal since 1977 and are classified in the category of drugs whose trafficking and use are most severely sanctioned.

United Nations

The member states of the UN signed the “ Convention on Psychotropic Substances ” in 1971 , following the recommendations of the UN's Narcotics Control Council (INCB). In 1986, under pressure from the USA, MDMA was included in Appendix 1 of the Convention.

See also

literature

- Hermle L., Schuldt F .: MDMA. In: von Heyden M., Jungaberle H., Majić T. (eds) Handbook of Psychoactive Substances. Springer Reference Psychology. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2018, pp. 551-565, doi: 10.1007 / 978-3-642-55125-3_25 , ISBN 978-3-642-55125-3

- Y. Vegting, L. Reneman, J. Booij: The effects of ecstasy on neurotransmitter systems: a review on the findings of molecular imaging studies. In: Psychopharmacology. Volume 233, number 19-20, October 2016, pp. 3473-3501, doi: 10.1007 / s00213-016-4396-5 , PMID 27568200 , PMC 5021729 (free full text) (review).

- F. Mueller, C. Lenz, M. Steiner, PC Dolder, M. Walter, UE Lang, ME Liechti, S. Borgwardt: Neuroimaging in moderate MDMA use: A systematic review. In: Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews. Volume 62, March 2016, pp. 21–34, doi: 10.1016 / j.neubiorev.2015.12.010 . PMID 26746590 (Review).

- JS Meyer: 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA): current perspectives. In: Substance abuse and rehabilitation. Volume 4, 2013, pp. 83-99, doi: 10.2147 / SAR.S37258 . PMID 24648791 , PMC 3931692 (free full text) (review).

- C. Michael White: How MDMA's pharmacology and pharmacokinetics drive desired effects and harms. In: Journal of clinical pharmacology. Volume 54, Number 3, March 2014, pp. 245-252, doi: 10.1002 / jcph.266 . PMID 24431106 (Review).

- S. Selvaraj, R. Hoshi, et al. a .: Brain serotonin transporter binding in former users of MDMA ('ecstasy'). In: The British Journal of Psychiatry. 194, 2009, p. 355, doi: 10.1192 / bjp.bp.108.050344 .

- AC Parrott: The potential dangers of using MDMA for psychotherapy. In: Journal of psychoactive drugs. Volume 46, number 1, Jan-Mar 2014, pp. 37-43, doi: 10.1080 / 02791072.2014.873690 . PMID 24830184 (Review).

- MH Baumann, RB Rothman: Neural and cardiac toxicities associated with 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA). In: International review of neurobiology. Volume 88, 2009, pp. 257-296, doi: 10.1016 / S0074-7742 (09) 88010-0 . PMID 19897081 , PMC 3153986 (free full text).

- AR Green: The pharmacology and clinical pharmacology of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, "ecstasy"). In: Pharmacol. Rev. Volume 55, 2003, pp. 463-508. PMID 12869661 HTML PDF; 402 kB (PDF)

Web links

- The Federal Center for Health Education: Drugcom: Drogenlexikon: Ecstasy. In: drugcom.de. December 5, 2014, accessed January 26, 2017 .

- MDMA - Information from the European Monitoring Center for Drugs and Drug Addiction

- Kathrin Zinkant: MDMA: Equasy is more dangerous than ecstasy. In: zeit.de . March 20, 2014, accessed June 11, 2015 .

- Ecstasy - Colorful stimulants with a deadly risk. In: sueddeutsche.de . October 28, 2013, accessed June 11, 2015 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ T. Passie, U. Benzenhöfer: MDA, MDMA, and other "mescaline-like" substances in the US military's search for a truth drug (1940s to 1960s). In: Drug testing and analysis. Volume 10, number 1, January 2018, pp. 72-80, doi: 10.1002 / dta.2292 , PMID 28851034 (review).

- ↑ a b c R. W. Freudenmann u. a .: The origin of MDMA (ecstasy) revisited: the true story reconstructed from the original documents. In: Addiction. Volume 101, 2006, pp. 1241-1245. PMID 16911722 ( PDF ).

- ↑ a b Methylenedioxymethamphetamine hydrochloride. Retrieved November 18, 2017 .

- ^ The Merck Index. An Encyclopaedia of Chemicals, Drugs and Biologicals. 14th edition. 2006, ISBN 0-911910-00-X , p. 996.

- ↑ a b SWGDRUG Monographs: 3,4-METHYLENEDIOXYMETHAMPHETAMINE (PDF; 574 kB), accessed on May 20, 2013.

- ↑ Entry on 3,4-methylenedioxy-N-methylamphetamine. In: Römpp Online . Georg Thieme Verlag, accessed on June 5, 2014.

- ↑ a b c data sheet (±) -3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine hydrochloride from Sigma-Aldrich , accessed on April 8, 2011 ( PDF ).

- ↑ Party Drug: The Deadly Legend of Molly Clean . World Online , News Panorama.

- ↑ F. Haber: About some derivatives of the piperonal. In: Reports of the German Chemical Society. 24, 1891, pp. 617-626.

- ↑ F. Haber: About some derivatives of the Piperonals. Dissertation . Schade, Berlin 1891.

- ↑ a b U. Benzenhöfer, T. Passie: To the early history of Ecstasy . In: Der Nervenarzt , Volume 77, 2006, pp. M95 – M99. PMID 16397805 ( PDF ).

- ^ Merck company: Merck company annual report. 1912.

- ↑ Patent DE 274350 from E. Merck in Darmstadt: Process for the preparation of alkyloxyaryl, dialkyloxyaryl and alkylenedioxyarylaminopropanes or their derivatives monoalkylated on the nitrogen. filed December 24, 1912, issued May 16, 1914.

- ↑ C. Beck: Yearbook for Ethnomedicine. 1997/1998, pp. 95-125.

- ↑ S. Bernschneider-Reif u. a .: The origin of MDMA ("ecstasy") - separating the facts from the myth. In: Pharmacy. 61, 2006, pp. 966-972. PMID 17152992

- ↑ RW Freudenmann u. a .: The origin of MDMA (ecstasy) revisited: the true story reconstructed from the original documents. In: Addiction. 101, 2006, pp. 1241-1245. PMID 16911722 .

- ^ The Federal Center for Health Education: Drugcom: Top Topic: Ecstasy (MDMA) - a story with detours .

- ↑ WE Ehrich, EB Krumbhaar: An article contributed to an anniversary volume in honor of doctor joseph hersey pratt: The effects of large doses of benzedrine sulphate on the albino rat: functional and tissue changes. In: Annals of Internal Medicine. 10, 1937, p. 1874. doi: 10.7326 / 0003-4819-10-12-1874 .

- ↑ a b U. Benzenhöfer, T. Passie: Rediscovering MDMA (ecstasy): the role of the American chemist Alexander T. Shulgin. In: Addiction. Volume 105, number 8, August 2010, pp. 1355-1361, doi: 10.1111 / j.1360-0443.2010.02948.x . PMID 20653618 , ( PDF ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , Accessed on October 8, 2015)

- ↑ Nicolae Sfetcu: Health & Drugs: Disease, Prescription & Medication. 2014, (excerpts online)

- ↑ Julie Holland: Ecstasy: The Complete Guide: A Comprehensive Look at the Risks and Benefits of MDMA. Park Street Press, 2001. (Excerpts online)

- ↑ a b c T. Passie, U. Benzenhöfer: The History of MDMA as an Underground Drug in the United States, 1960–1979. In: Journal of psychoactive drugs. Volume 48, number 2, 2016 Apr-Jun, pp. 67-75, doi: 10.1080 / 02791072.2015.1128580 , PMID 26940772 .

- ↑ Shulgin, Alexander, Ann Shulgin: PIHKAL - A Chemical Love Story. Transform Press, 1995. Section on MDA , accessed October 8, 2015.

- ↑ Shulgin AT, Nichols DE Characterization of three new psychotomimetics. In: Stillman RC, Willette RE, editors. The Psychopharmacology of Hallucinogens. New York: Pergamon Press; 1978, pp. 74-83.

- ↑ US will ban 'Ecstasy', a hallucinogenic drug. In: New York Times . June 1, 1985.

- ↑ Only an incomprehensible grunt . In: Der Spiegel . No. 26 , 1987 ( online ).

- ↑ a b c d German Observatory for Drugs and Drug Addiction: 2014 report from the national REITOX hub to the EMCDDA. ( PDF ( Memento of the original from February 4, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this note. , Accessed on December 21, 2014)

- ↑ a b c d e f g Tim Pfeiffer-Gerschel, Stephanie Flöter, Ingo Kipke, Lisa Jakob, Alicia Casati (IFT Institute for Therapy Research (Epidemiology and Coordination) for the German Monitoring Center for Drugs and Drug Addiction): 2013 report from the national REITOX hub to the EMCDDA . ( Memento of the original from September 5, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. November 5, 2013, accessed April 23, 2014.

- ↑ a b c d e f European Drugs Report 2013 . ( Memento of the original from September 5, 2014 in the Internet Archive ; PDF) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. European Monitoring Center for Drugs and Drug Addiction; Retrieved April 23, 2014

- ^ T in the Park festival given fake ecstasy pill warning. In: BBC News. March 13, 2014, accessed March 13, 2014 .

- ↑ Table PPP-9. Composition of illicit drug tablets, 2011. European Monitoring Center for Drugs and Drug Addiction

- ↑ Maurice Thiriet: Ecstasy consumption is becoming more and more risky. In: Tagesanzeiger , December 30, 2008.

- ↑ pill warnings from Eve & Rave Switzerland . Archived from the original on September 4, 2009. Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Retrieved January 22, 2010.

- ^ Gesundheit Österreich GmbH, ÖBIG division: Report on the drug situation 2009 ( Memento of the original from December 10, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 1.1 MB), p. 75.

- ↑ German Observatory for Drugs and Drug Addiction (DBDD): 2009 report from the national REITOX hub to the EMCDDA. ( Memento of the original from September 23, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 951 kB), p. 159.

- ↑ 5 things you should know about 'Molly' ; HLNtv.com

- ^ 9 things everyone should know about the drug Molly , CNN.com

- ↑ Cadillac and Ecstasy . In: Der Spiegel . No. 9 , 1989 ( online ).

- ↑ MDMA ; drugscouts.de

- ↑ a b Sven Stockrahm: Ecstasy consumption: a trip for five euros. In: Zeit Online , April 14, 2014.

- ^ RB Rothman, MH Baumann: Therapeutic and adverse actions of serotonin transporter substrates. In: Pharm. Ther. Volume 95, 2002, pp. 73-88. PMID 12163129 .

- ↑ Alexander Shulgin, Ann Shulgin: PIHKAL - A Chemical Love Story. Transform Press, ISBN 0-9630096-0-5 .

- ↑ David E. Nichols: Differences Between the Mechanism of Action of MDMA, MBDB, and the Classic Hallucinogens. Identification of a New Therapeutic Class: Entactogens. In: Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 18, 1986, pp. 305-313, doi: 10.1080 / 02791072.1986.10472362 .

- ↑ C. Michael White: How MDMA's pharmacology and pharmacokinetics drive desired effects and harms. In: Journal of clinical pharmacology. Volume 54, Number 3, March 2014, pp. 245-252, doi: 10.1002 / jcph.266 . PMID 24431106 (Review).

- ↑ a b c J. S. Meyer: 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA): current perspectives. In: Substance abuse and rehabilitation. Volume 4, 2013, pp. 83-99, doi: 10.2147 / SAR.S37258 , PMID 24648791 , PMC 3931692 (free full text) (review).

- ↑ G. Bedi, D. Hyman, H. de Wit: Is ecstasy an "empathogen"? Effects of ± 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine on prosocial feelings and identification of emotional states in others. In: Biological psychiatry. Volume 68, Number 12, December 2010, pp. 1134-1140, doi: 10.1016 / j.biopsych.2010.08.003 . PMID 20947066 , PMC 2997873 (free full text).

- ^ MA Miller, AK Bershad, H. de Wit: Drug effects on responses to emotional facial expressions: recent findings. In: Behavioral pharmacology. Volume 26, Number 6, September 2015, pp. 571-579, doi: 10.1097 / FBP.0000000000000164 . PMID 26226144 , PMC 4905685 (free full text) (review).

- ^ CG Frye, MC Wardle, GJ Norman, H. de Wit: MDMA decreases the effects of simulated social rejection. In: Pharmacology, biochemistry, and behavior. Volume 117, February 2014, pp. 1–6, doi: 10.1016 / j.pbb.2013.11.030 . PMID 24316346 , PMC 3910346 (free full text).

- ↑ CM Hysek, Y. Schmid, LD Simmler, G. Domes, M. Heinrichs, C. Eisenegger, KH Preller, BB Quednow, ME Liechti: MDMA enhances emotional empathy and prosocial behavior. In: Social cognitive and affective neuroscience. Volume 9, Number 11, November 2014, pp. 1645–1652, doi: 10.1093 / scan / nst161 . PMID 24097374 , PMC 4221206 (free full text).

- ↑ CM Hysek, G. Domes, ME Liechti: MDMA enhances "mind reading" of positive emotions and impairs "mind reading" of negative emotions. In: Psychopharmacology. Volume 222, Number 2, July 2012, pp. 293-302, doi: 10.1007 / s00213-012-2645-9 . PMID 22277989 .

- ↑ a b c Hermle L., Schuldt F. (2018) MDMA. In: von Heyden M., Jungaberle H., Majić T. (eds) Handbook of Psychoactive Substances. Springer Reference Psychology. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg 2018, pp. 551-565, doi: 10.1007 / 978-3-642-55125-3_25

- ↑ PK McGuire, H. Cope, TA Fahy: Diversity of psychopathology associated with use of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine ('Ecstasy'). In: The British journal of psychiatry: the journal of mental science. Volume 165, Number 3, September 1994, pp. 391-395. PMID 7994514 .

- ^ RP Litjens, TM Brunt, GJ Alderliefste, RH Westerink: Hallucinogen persisting perception disorder and the serotonergic system: a comprehensive review including new MDMA-related clinical cases. In: European neuropsychopharmacology: the journal of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology. Volume 24, number 8, August 2014, pp. 1309–1323, doi: 10.1016 / j.euroneuro.2014.05.008 . PMID 24933532 (Review).

- ↑ L. Hanck, AF Schellekens: Hallucinogen persisting perception disorder after ecstasy use. In: Nederlands tijdschrift voor geneeskunde. Volume 157, number 24, 2013, p. A5649. PMID 23759176 .

- ↑ a b Review in: F. Rugani, S. Bacciardi, L. Rovai, M. Pacini, AG Maremmani, J. Deltito, L. Dell'osso, I. Maremmani: Symptomatological features of patients with and without Ecstasy use during their first psychotic episode. In: International journal of environmental research and public health. Volume 9, Number 7, July 2012, pp. 2283–2292, doi: 10.3390 / ijerph9072283 . PMID 22851941 , PMC 3407902 (free full text).

- ↑ G. Gerra, A. Zaimovic, R. Ampollini, F. Giusti, R. Delsignore, MA Raggi, G. Laviola, T. Macchia, F. Brambilla: Experimentally induced aggressive behavior in subjects with 3,4-methylenedioxy-methamphetamine ("Ecstasy") use history: psychobiological correlates. In: Journal of substance abuse. Volume 13, Number 4, 2001, pp. 471-491. PMID 11775077 .

- ↑ HV Curran, H. Rees, T. Hoare, R. Hoshi, A. Bond: Empathy and aggression: two faces of ecstasy? A study of interpretative cognitive bias and mood change in ecstasy users. In: Psychopharmacology. Volume 173, Number 3-4, May 2004, pp. 425-433, doi: 10.1007 / s00213-003-1713-6 . PMID 14735288 .

- ↑ On Tuesday after a weekend of dancing. Risk Factors and Lifestyle. In: derStandard.at ›Health.

- ↑ a b c A. C. Parrott, C. Montgomery, MA Wetherell, LA Downey, C. Stough, AB Scholey: MDMA, cortisol, and heightened stress in recreational ecstasy users. In: Behavioral pharmacology. Volume 25, number 5-6, September 2014, pp. 458-472, doi: 10.1097 / FBP.0000000000000060 . PMID 25014666 (Review).

- ↑ AC Parrott, J. Lock, AC Conner, C. Kissling, J. Thome: Dance clubbing on MDMA and during abstinence from Ecstasy / MDMA: prospective neuroendocrine and psychobiological changes. In: Neuropsychobiology. Volume 57, number 4, 2008, pp. 165-180, doi: 10.1159 / 000147470 , PMID 18654086 , PMC 3575116 (free full text).

- ↑ a b A. C. Parrott, HR Sands, L. Jones, A. Clow, P. Evans, LA Downey, T. Stalder: Increased cortisol levels in hair of recent Ecstasy / MDMA users. In: European neuropsychopharmacology: the journal of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology. Volume 24, number 3, March 2014, pp. 369–374, doi: 10.1016 / j.euroneuro.2013.11.006 , PMID 24333019 .

- ↑ a b D. Nutt, LA King, W. Saulsbury, C. Blakemore: Development of a rational scale to assess the harm of drugs of potential misuse . In: The Lancet . tape 369 , no. 9566 , March 24, 2007, p. 1047-1053 , doi : 10.1016 / S0140-6736 (07) 60464-4 , PMID 17382831 .

- ^ A b David J. Nutt, Leslie A. King, Lawrence D. Phillips: Drug harms in the UK: a multicriteria decision analysis . In: The Lancet . tape 376 , no. 9752 , November 6, 2010, p. 1558-1565 , doi : 10.1016 / S0140-6736 (10) 61462-6 , PMID 21036393 .

- ^ Robert Gable: Drug Toxicity. Retrieved February 17, 2011 .

- ↑ RS Gable: Acute toxicity of drugs versus regulatory status. In: JM Fish (Ed.): Drugs and Society. US Public Policy. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Lanham, MD 2006, ISBN 0-7425-4244-0 , pp. 149-162.

- ↑ Drug deaths by cause of death 2010 - country survey . ( Memento of the original from December 23, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Drug Commissioner of the Federal Government, March 24, 2011; accessed on October 14, 2015.

- ↑ Narcotics deaths by cause of death 2013 - country survey . ( Memento of the original from February 9, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Drug Commissioner of the Federal Government, April 17, 2014; accessed on October 14, 2015.

- ↑ Federal Criminal Police Office: Narcotics crime: Federal situation report 2014 - table annex . (PDF) 2015, accessed April 28, 2016.

- ↑ Federal Criminal Police Office: Narcotics crime: Federal situation report 2015 - table annex . (PDF) 2016, accessed October 29, 2016.

- ↑ Federal Drug Situation Report 2016 - Annex of tables (PDF)

- ↑ Federal Drug Situation Report 2017 - Annex to tables (PDF)

- ↑ Joachim Schille, Helmut Arnold: Practical Handbook Drugs and Drug Prevention. 2002, ISBN 3-7799-0783-6 , p. 90.

- ↑ Ecstasy / MDMA - checkit! .

- ↑ MDMA (methylenedioxy-N-methylamphetamine); Ecstasy; XTC; Drug Information Berlin .

- ↑ Murder charges after fatal MDMA overdose . March 16, 2010.

- ^ What Martha's sad death from Ecstasy can teach us. Telegraph.

- ↑ Erowid.org , accessed December 25, 2014.

- ^ JR Gill, JA Hayes, IS deSouza, E. Marker, M. Stajic: Ecstasy (MDMA) deaths in New York City: a case series and review of the literature. In: J Forensic Sci. 47 (1), Jan 2002, pp. 121-126. PMID 12064638 .

- ↑ MZ Karlovsek, A. Alibegović, J. Balazic: Our experiences with fatal ecstasy abuse (two case reports). In: Forensic Sci Int. 147 Suppl, Jan 17, 2005, pp. 77-80. PMID 15694737 .

- ↑ F. Schifano, A. Oyefeso, J. Corkery, K. Cobain, R. Jambert-Gray, G. Martinotti, AH Ghodse: Death rates from ecstasy (MDMA, MDA) and polydrug use in England and Wales 1996-2002. In: Hum Psychopharmacol. 18 (7), Oct 2003, pp. 519-524. PMID 14533133 .

- ↑ Think Like a Doctor: The Girl in a Coma Solved. In: nytimes.com. October 5, 2012, accessed October 15, 2012 .

- ^ UD McCann, FP Sgambati, AR Schwartz, GA Ricaurte: Sleep apnea in young abstinent recreational MDMA ("ecstasy") consumers. In: Neurology. Dec 2, 2009. PMID 19955499 .

- ↑ a b T. Schilt, MM de Win, M. Koeter, G. Jager, DJ Korf, W. van den Brink, B. Schmand: Cognition in novice ecstasy users with minimal exposure to other drugs: a prospective cohort study. In: Archives of general psychiatry. Volume 64, Number 6, June 2007, pp. 728-736, doi: 10.1001 / archpsyc.64.6.728 . PMID 17548754 .

- ^ D. Wagner, B. Becker, P. Koester, E. Gouzoulis-Mayfrank, J. Daumann: A prospective study of learning, memory, and executive function in new MDMA users. In: Addiction. Volume 108, number 1, January 2013, pp. 136-145, doi: 10.1111 / j.1360-0443.2012.03977.x . PMID 22831704 .

- ↑ AC Parrott: MDMA, serotonergic neurotoxicity, and the diverse functional deficits of recreational 'Ecstasy' users. In: Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews. Volume 37, number 8, September 2013, pp. 1466–1484, doi: 10.1016 / j.neubiorev.2013.04.016 . PMID 23660456 (Review). ( PDF (PDF) accessed on October 27, 2014).

- ↑ JH Halpern, AR Sherwood, JI Hudson, S. Gruber, D. Kozin, HG Pope: Residual neurocognitive features of long-term ecstasy users with minimal exposure to other drugs. In: Addiction. Volume 106, number 4, April 2011, pp. 777-786, doi: 10.1111 / j.1360-0443.2010.03252.x , PMID 21205042 , PMC 3053129 (free full text).

- ↑ G. Rogers, J. Elston, R. Garside, C. Roome, R. Taylor, P. Younger, A. Zawada, M. Somerville: The harmful health effects of recreational ecstasy: a systematic review of observational evidence. In: Health technology assessment. Volume 13, Number 6, January 2009, pp. Iii-iv, ix, doi: 10.3310 / hta13050 . PMID 19195429 (Review).

- ↑ LE Halpin, SA Collins, BK Yamamoto: Neurotoxicity of methamphetamine and 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine. In: Life sciences. Volume 97, number 1, February 2014, pp. 37-44, doi: 10.1016 / j.lfs.2013.07.014 . PMID 23892199 , PMC 3870191 (free full text) (review).

- ^ A b C. A. Roberts, A. Jones, C. Montgomery: Meta-analysis of executive functioning in ecstasy / polydrug users. In: Psychological medicine. Volume 46, number 8, 06 2016, pp. 1581–1596, doi: 10.1017 / S0033291716000258 , PMID 26966023 , PMC 4873937 (free full text) (review).

- ↑ B. Esteban et al. a .: 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine induces monoamine release, but not toxicity, when administered centrally at a concentration occurring following a peripherally injected neurotoxic dose. In: Psychopharmacology. Volume 154, 2001, pp. 251-260. PMID 11351932 , doi: 10.1007 / s002130000645 .

- ↑ LS Seiden, KE Sabol: Methamphetamine and methylenedioxymethamphetamine neurotoxicity: possible mechanisms of cell destruction. In: NIDA research monograph. Volume 163, 1996, pp. 251-276. PMID 8809863 (Review).

- ↑ Beatriz Goni-Allo, Brian Ó Mathúna, Mireia Segura, Elena Puerta, Berta Lasheras, Rafael de la Torre, Norberto Aguirre: The relationship between core body temperature and 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine metabolism in rats: implications for neurotoxicity. In: Psychopharmacology. 197, 2008, pp. 263-278, doi: 10.1007 / s00213-007-1027-1 .

- ↑ JE Malberg, LS Seiden: Small changes in ambient temperature cause large changes in 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) -induced serotonin neurotoxicity and core body temperature in the rat. In: The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. Volume 18, Number 13, July 1998, pp. 5086-5094. PMID 9634574 .

- ↑ Clara Touriño, Andreas Zimmer, Olga Valverde, Dawn N. Albertson: THC Prevents MDMA Neurotoxicity in Mice. In: PLoS ONE. 5, 2010, p. E9143, doi: 10.1371 / journal.pone.0009143 .

- ^ KC Morley, KM Li, GE Hunt, PE Mallet, IS McGregor: Cannabinoids prevent the acute hyperthermia and partially protect against the 5-HT depleting effects of MDMA ("Ecstasy") in rats. In: Neuropharmacology . Volume 46, Number 7, June 2004, pp. 954-965, doi: 10.1016 / j.neuropharm.2004.01.002 . PMID 15081792 .

- ↑ GJ Dumont, C. Kramers, FC Sweep, DJ Touw, JG van Hasselt, M. de Kam, JM van Gerven, JK Buitelaar, RJ Verkes: Cannabis coadministration potentiates the effects of "ecstasy" on heart rate and temperature in humans. In: Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics. Volume 86, Number 2, August 2009, pp. 160-166, doi: 10.1038 / clpt.2009.62 . PMID 19440186 , PDF, pp. 121-138. (PDF) accessed on October 23, 2015.

- ↑ E. Gouzoulis-Mayfrank et al. a .: Neurotoxic long-term damage in ecstasy (MDMA) users - overview of the current state of knowledge. In: The neurologist. Volume 73, 2002, pp. 405-421. PMID 12078018 , doi: 10.1007 / s00115-001-1243-6 .

- ↑ F. Sjöqvist: Psychotropic drugs (2): Interaction between monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitors and other substances. In: Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine. Volume 58, Number 11 Part 2, November 1965, pp. 967-978. PMID 4952963 , PMC 1898666 (free full text) (review).

- ^ MG Livingston, HM Livingston: Monoamine oxidase inhibitors: An update on drug interactions. In: Drug safety. Volume 14, Number 4, April 1996, pp. 219-227. PMID 8713690 (Review).

- ↑ JP Finberg: Update on the pharmacology of selective inhibitors of MAO-A and MAO-B: focus on modulation of CNS monoamine neurotransmitter release. In: Pharmacology & therapeutics. Volume 143, number 2, August 2014, pp. 133–152, doi: 10.1016 / j.pharmthera.2014.02.010 . PMID 24607445 (Review).

- ↑ MJ Smilkstein, SC Smolinske, BH Rumack: A case of MAO inhibitor / MDMA interaction: agony after ecstasy. In: Journal of toxicology. Clinical toxicology. Volume 25, Numbers 1-2, 1987, pp. 149-159. PMID 2884326 .

- ^ DI Brierley, C. Davidson: Developments in harmine pharmacology: implications for ayahuasca use and drug-dependence treatment. In: Progress in neuro-psychopharmacology & biological psychiatry. Volume 39, Number 2, December 2012, pp. 263-272, doi: 10.1016 / j.pnpbp.2012.06.001 . PMID 22691716 (Review).

- ↑ RS Gable: Risk assessment of ritual use of oral dimethyltryptamine (DMT) and harmala alkaloids. In: Addiction. Volume 102, Number 1, January 2007, pp. 24-34, doi: 10.1111 / j.1360-0443.2006.01652.x . PMID 17207120 (Review).

- ^ E. Vuori, JA Henry, I. Ojanperä, R. Nieminen, T. Savolainen, P. Wahlsten, M. Jäntti: Death following ingestion of MDMA (ecstasy) and moclobemide. In: Addiction. Volume 98, Number 3, March 2003, pp. 365-368. PMID 12603236 .

- ↑ JL Pilgrim, D. Gerostamoulos, N. Woodford, OH Drummer: Serotonin toxicity involving MDMA (ecstasy) and moclobemide. In: Forensic science international. Volume 215, number 1-3, February 2012, pp. 184-188, doi: 10.1016 / j.forsciint.2011.04.008 . PMID 21570786 .

- ↑ European Drugs Report 2015 . ( Memento of the original from August 12, 2015 in the Internet Archive ; PDF) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. European Monitoring Center for Drugs and Drug Addiction; accessed on September 16, 2015.

- ^ C. Ort, AL van Nuijs, JD Berset, L. Bijlsma, S. Castiglioni, A. Covaci, P. de Voogt, E. Emke, D. Fatta-Kassinos, P. Griffiths, F. Hernández, I. González -Mariño, R. Grabic, B. Kasprzyk-Hordern, N. Mastroianni, A. Meierjohann, T. Nefau, M. Ostman, Y. Pico, I. Racamonde, M. Reid, J. Slobodnik, S. Terzic, N . Thomaidis, KV Thomas: Spatial differences and temporal changes in illicit drug use in Europe quantified by wastewater analysis. In: Addiction. Volume 109, number 8, August 2014, pp. 1338–1352, doi: 10.1111 / add.12570 . PMID 24861844 , PMC 4204159 (free full text).

- ↑ Henrik Jungaberle, Peter Gasser, Jan Weinhold, Rolf Verres (eds.): Therapy with psychoactive substances. Practice and criticism of psychotherapy with LSD, psilocybin and MDMA. Bern 2008.

- ↑ Kai Kupferschmidt: The Highlung. In: tagesanzeiger.ch. February 8, 2011, accessed May 13, 2015 .

- ↑ schamanismus-information.de .

- ↑ Torsten Passie, Thomas Dürst: Healing Processes in Altered Consciousness. Elements of psycholytic therapy experiences from the perspective of patients, Berlin 2009, p. 19.

- ↑ Hans-Peter Waldrich with the collaboration of Gabriele Markert: Brainwashing or Cure? Experience with drug-based psychotherapy. Hamburg 2014.

- ↑ Henrik Jungaberle, Rolf Verres: Rules and standards in substance-supported psychotherapy (SPT). In: Henrik Jungaberle, Peter Gasser u. a .: Therapy with psychoactive substances. Pp. 41-109, pp. 103ff.

- ↑ Petition 36693: Authorization of MDMA as a medicinal product from October 2, 2012. Accessed December 21, 2014.

- ↑ Home - Jonge Democrats .

- ↑ all-in.de . Archived from the original on June 12, 2015. Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Retrieved May 17, 2015.

- ↑ Second Narcotics Law Amendment Ordinance of July 23, 1986, available from Eve & Rave : 2. BtMÄndV

- ↑ Alexander 'Sasha' Shulgin , shulginresearch.org.