leprosy

Leprosy (also called leprosy , since the 13th century, and already in Middle High German called leprosy ) is a chronic infectious disease with a long incubation period, which is triggered by Mycobacterium leprae and is associated with noticeable changes in the skin, mucous membranes, nerve tissue and bones. Microscopic evidence was provided by the Norwegian Gerhard Armauer Hansen in 1873 , after whom the disease was also known as Hansen's disease or Hansen's disease (English Hansen's disease , HD, or leprosy) referred to as. In Austria the disease and in Germany proof of the pathogen is notifiable .

Etymology and synonyms

The term leprosy was only used in German in the 18th and 19th centuries. It was used in the 19th century and is borrowed from the Greco-Latin word lépra . This is derived from the Greek adjective leprós , which means "scaly, rough". The associated Greek verb lépein means "peel off".

The original German name of the disease is leprosy . The sick affected by leprosy had to live outside human settlements - they were exposed (by society) and thus singled out from the society of their fellow human beings. However, the equality of meaning between leprosy and leprosy did not arise until the 13th century. Previously, the word leprosy could also stand for other symptoms and illnesses that led to the elimination or "exposure" of those affected, such as ergotism or psoriasis .

German translations of the Hebrew Torah translated as leprosy , the word Zaraat ( Hebrew צרעת), the "snow-white leprosy" on skin, clothing and houses (see Exodus 4: 6–7 and 4:30 EU ; Leviticus 13: 2, 13:47 and 14:34 EU EU ; 4. Book of Moses 12:10 EU ). According to Maimonides , the word Zaraat denotes a symbolic change that is intended to punish and warn against gossip , slander and gossip (Hebrew: laschon hara ).

Which today no longer common synonym Miselsucht (from Middle High German miselsuht "leprosy, leprosy") is derived from the Latin word misellus , the "poor" and means "unfortunate".

In the Middle Ages, leprosy was also called Lazarus disease . To isolate (segregate) the lepers, infirmaries (also known as special infirmaries ) were built outside the cities , which were also called Lazarus houses. That is why today some suburbs are called Saint Lazare in France and San Lazzaro in Italy . The German word Lazarett has the same origin .

story

origin

In line with the migratory movements of early humans, the origin of leprosy is assumed to be in East Africa : tens of thousands of years ago the bacteria would have spread from there on the one hand northwest to Europe and on the other hand east to India and the Far East. A second assumption is based on the possibility of an oriental origin (in India).

The leprosy pathogen has hardly changed genetically in the time it has spread around the world, which is extremely unusual for bacteria. Despite the very small genetic differences, the route of spread of leprosy could be determined with a high degree of accuracy.

antiquity

Leprosy is one of the oldest known diseases. She was a. detected in 4000 year old finds in India. It is already used in Egyptian papyri such as B. the Papyrus Hearst (around 1500 BC) mentioned and is paleopathologically secured for Egypt from the Middle Kingdom . Prayers among the Hittites, but also the plague gods of the Orient, are sometimes associated with leprosy, so that leprosy was probably also known and widespread in the Iron Age Orient. Around 250 BC The disease "leprosy" is said to have been described in detail for the first time by Greek and Egyptian doctors.

The Hebrew name Zaraat (or Ṣaarʿat) describes lighter skin diseases in the Book of Leviticus (in the 13th and 14th chapters). It is questionable whether this is leprosy. Whether leprosy is reported in the Bible at all is still a matter of dispute (see above). One of the well-known stories from the Gospels is the healing of a leper .

It is assumed that, due to the incomplete medical knowledge, many skin diseases were previously grouped under terms such as leprosy or "leprosy". B. could differentiate between lupus (butterfly lichen) and psoriasis (psoriasis). It is therefore almost never possible to determine with certainty what a leper mentioned in the traditions was actually affected by.

Leprosy was also a common disease in Roman times, preferably in poorer sections of the population. At the time of Cicero , in the first century BC, leprosy is documented in large parts of the population in Greece and Italy. Contagion was already a known and feared phenomenon here. Sick people were therefore often expelled from the community and contact with them avoided, which ultimately led to the German term "leprosy".

Middle Ages and early modern times

For a long time it was assumed that only two strains of leprosy bacteria appeared in the Middle Ages, but in 2017 the existence of all ten known strains could already be proven during this time. The oldest genome sequenced is from Great Chesterford Cemetery in England. It is dated between 415 and 545 and belongs to the same strain of leprosy that has been detected in today's squirrels . This could indicate that leprosy spread with the fur trade. Leprosy was found among the Lombards in the 7th and 8th centuries, but it was also widespread in the Franconian Empire. The leprosarium on the Königsstrasse to Maastricht in Aachen-Melaten can be dated to the 8th century according to excavation results. A leprosy chapter can be found (on pages 21v to 22v) in the Lorsch Pharmacopoeia from the end of the 8th century.

From the 11th century onwards, the leprosy houses developed in the vicinity of larger cities, a form of hospice of their own. A hospital for lepers was founded in Würzburg in the 11th century (more Würzburg leprosoria followed). The Bremen Leprosenhaus St. Remberti Hospital , which was dedicated to Saint Rembert , was first mentioned in a document in the 13th century. A complete ensemble of infirmary, chapel, wayside shrine for collecting alms and a leper cemetery has been preserved in Trier .

The more general prevalence of leprosy in Europe during the Middle Ages is often attributed to the Crusades . It reached its peak in the 13th century and at the end of the 16th century largely disappeared from the list of chronic widespread diseases in Central Europe. The reason for their disappearance was unknown. It was assumed that a new hygiene awareness brought with them by the returning crusaders moved into Europe, which resulted in new bathhouses being built everywhere. Another reason is also seen in other epidemics that can quickly lead to death, such as plague, cholera and typhus, which found an ideal distribution environment in the weakened leprosy people who lived in close quarters under precarious conditions.

In the Middle Ages was the first time based on specific symptoms that both the leprosy scene described in heilkundlicher (from the 13th century in diagnostic short treatises) and also in fiction, leprosy (or miselsuht ) diagnostically detected. Such leprosy symptoms include an early insensitivity to pain, particularly in the area of the Achilles tendon , as described by Guy de Chauliac in 1363 . One of the more extensive leprashau texts in German, which also contains borrowings from the Libellus de signis leprosorum (around 1300) by Arnald von Villanova , can be found in a pharmacopoeia written around 1495 by Anton Trutmann .

In the course of the discovery of the sea route to India, the discovery of America and the colonization of Africa, and in particular the slave trade , the pathogen came among other things. to Indonesia, West Africa and America as well as to the Caribbean, the Pacific and Brazil.

In Europe, lepers were often declared "civilly dead" in the Middle Ages and were forced to wear a Lazarus dress in public (outside of a leprosarium ) and to use a warning rattle or bell so that others could create a spatial distance .

Memel

In Prussia, the first leprosy patient was reported in the Memel district in 1848 . In 1894 there were more. At the suggestion of Robert Koch , the only leprosy home in Germany was built in 1898/99. It was 2 km north of Memel and could take 16, from 1909 22 patients. The number of cases reported by September 30, 1944 was 42 men and 52 women. The medical management of the home and the treatment of the sick was always entrusted to the respective district doctor (official doctor) as an epidemic specialist. The two nurses came from the Königsberg Deaconess Mother House of Mercy. In October 1944 the sick people in the leprosy home were transferred to Koenigsberg (Prussia) under the most difficult of circumstances and handed over to the care of the Deaconess Hospital of Mercy. Only one of the sick remained alive.

The fight against leprosy

Meyer's Konversationslexikon indicates in 1888 that leprosy occurred regularly in Scandinavia, Iceland and the Iberian Peninsula, in Provence and on the Italian coasts, in Greece and on the islands of the Mediterranean. However, leprosy was already on the decline across Europe and no longer comparable with the figures of antiquity and the Middle Ages.

Carl Wilhelm Boeck, a Norwegian dermatologist, had, together with Daniel Cornelius Danielssen , the director of the leprosy hospital in Bergen, divided leprosy into a tubercular and an anesthetic form for the first time.

He said that the disease was still very widespread in Norway in the 19th century. He concluded this from a census, with 2119 lepers being registered in 1862 out of a population of less than two million. In Germany only a few cases were registered at the same time, which occurred particularly in East Prussia. This gave rise to the idea that northern Europeans are more likely to be contaminated with disease than central or southern Europeans. The same pattern was assumed for Eastern Europe versus Western Europe. In fact, the counts of leprosy cases during this period are very unreliable. It is known that leprosy was still quite common at the time of the Russian tsars.

A first major step forward in the fight against leprosy was the discovery of the pathogen, the bacterium Mycobacterium leprae , by the Norwegian doctor Gerhard Armauer Hansen in 1873. Albert Neisser then used a special staining method to make the pathogen bacteriologically investigatable. On September 28, 1884, the German dermatologist Eduard Arning began a four-year human experiment on the then 48-year-old previously healthy Polynesian Keanu , which provided evidence of the transferability of leprosy and led to Keanu's death.

The religious priest Damian de Veuster looked after around 600 expelled lepers on the Hawaiian island of Moloka'i from 1873 and thus became the "apostle of lepers". He became infected and died of the consequences in 1889. Today he is venerated as a saint. The Damien-Dutton Award , an award for commitment in the fight against leprosy, is named after him and another helper. The British nurse Kate Marsden (1859–1931) campaigned for lepers in Yakutia .

In Japan, the first specialized hospital was established by Gotō Masafumi in 1870 , and statutory disease controls were introduced in 1907. In the 20th century, infected people were treated inhumanely in Japan. Under a 1953 law, they were imprisoned for life in closed institutions even when treatment was available. Many were forcibly sterilized and pregnant women were forced to have abortions . The law was not repealed until 1996. In 1995 about 12,000 patients were counted. The last private sanatoriums were closed in 2006/2007. In 2009 there were still 13 state leprosy sanatoriums with 2568 remaining patients, most of whom had spent their entire lives there, so that reintegration into Japanese society is hardly possible. These inmates, who have no offspring due to the forced sterilization, are now over 80 years old on average. For years, parliament has been working unsuccessfully on a compensation law.

Legally prescribed reports of epidemic diseases such as leprosy were consistently mandatory in the Eastern Bloc between 1949 and 1975 as part of preventive health care and are therefore very well documented. Here, too, only individual cases were reported, mainly due to immigration.

The number of registered leprosy patients declined significantly in most regions between 1985 and 1993: Today leprosy occurs mainly in India, Indonesia, Africa, South America and the Pacific.

| Geographic region | 1985 | 1990 | 1993 | Change between 1985 and 1993 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asia | 3,812,049 | 2,793,017 | 1,708,528 | −55.2% |

| Africa | 987.607 | 482,669 | 194,666 | −80.3% |

| South America | 305,999 | 301,704 | 313,446 | + 2.4% |

| Pacific | 245.753 | 125,739 | 67,067 | −72.7% |

| Europe | 16,794 | 7,246 | 7,874 | −53.1% |

| world | 5,368,202 | 3,710,375 | 2,291,581 | −57.3% |

Recent research

Older research mainly assumed that leprosy was mainly driven back by tuberculosis . People weakened by leprosy are often also infected with tuberculosis, which kills the sick quickly and thus prevents the spread of leprosy.

However, modern research thinks more of a kind of natural selection through genetic causes, since paleoepidemiologically, with the retreat of leprosy, more cases of psoriasis have been identified, with both diseases apparently mutually exclusive.

In the latest study by a Danish group, it was shown for the first time on the basis of leprosy victims from medieval Odense that there was a certain genetic selection. People with a certain variant of the immune gene HLA-DRB1 were significantly more susceptible to infection. This gene plays an important role in recognizing the pathogen Mycobacterium leprae. In today's Europeans, this weakened variant is significantly rarer and has been selected out by leprosy itself. The susceptible variant is the least common among northern Europeans. Lepers no longer passed the genetic risk factors on because they did not produce offspring.

Epidemiology

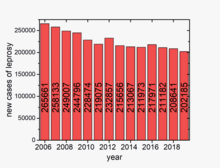

Thanks to the cooperation of all globally active leprosy relief organizations in the ILEP (International Federation of Anti-Leprosy Associations), leprosy is now under control. The number of new infections worldwide has declined significantly for decades and has only been falling slowly since 2013 (see graphic). 202,185 new cases were reported in 2019; At the end of 2019, the number of sick patients was 177,175 ( WHO data from 160 countries). For 2020, the WHO recorded 127,396 new cases, 37% fewer than in the previous year. However, the WHO assumes that this is more due to incomplete detection and registration due to the COVID-19 pandemic than to an actual improvement.

It was the declared aim of the World Health Organization to eradicate the disease by 2005, similar to what has been achieved with smallpox . Due to the unusually long incubation period in leprosy, this cannot be assumed for a long time.

Developing countries

The disease remains a serious problem in many developing countries . Most of the sick live in India , where over 110,000 people develop the disease every year. Brazil (over 25,000 new cases annually) and Indonesia (over 15,000) are also very badly affected, but there are also many sick people in Africa . In many of the poor countries affected by leprosy, special treatment centers have been set up with development funds.

Countries with good health care

Due to the treatment options with antibiotics, leprosy has now been almost eradicated in countries with developed health care. From 2009 to 2014 there were no new cases in Europe; In 2019, 42 new patients were registered in Europe.

The last sanatoriums for lepers in Europe are the Sanatorio San Francisco de Borja in Spain with 29 lepers (2016, 2006: 62) and the clinic in Tichileşti in Romania with 19 residents in 2011.

Pathogen

Leprosy is caused by Mycobacterium leprae , which has many properties in common with other mycobacteria , such as the causative agent of tuberculosis , Mycobacterium tuberculosis . Thus M. leprae an acid-fast bacillus whose cell wall structure in many ways similar to other mycobacteria, such that it contains different mycolic acids and numerous waxes.

Another similarity is that M. leprae, like the tuberculosis pathogen, prevents its digestion in the lysosomes of the leukocytes and thus escapes the body's own immune system: the leprosy bacteria are phagocytosed by the leukocytes, but the endosomes with the enclosed bacteria afterwards not fused with the lysosomes (which take care of the digestion of the endosome contents). What prevents this fusion is still largely unknown, but recent studies have uncovered a close connection with protein kinase G, an enzyme produced by bacteria. Only through the hydrolases in the lysosomes would the bacteria be killed and finally digested, but in the endosomes of the leukocytes they can continue to multiply without being disturbed. After the leukocytes, the Schwann cells are finally attacked by the bacteria, which explains why, as a result, the nervous system of the patient in particular is attacked.

Cultivation of the pathogen in vitro has not yet succeeded. From 1960, however, it was possible to breed M. leprae in mouse paws. Because of their unusually low body temperature, nine-banded armadillos have been the group of animals suitable for breeding the pathogen since 1971 . This also makes them indispensable in vaccine research .

A disease similar to leprosy (lepromatosis) is caused - especially in South America - by the bacterium Mycobacterium lepromatosis .

transmission

Long-term, close contact with an infected person is required for transmission or infection with the pathogen. The transmission occurs through droplet infection . Since leprosy is only slightly contagious, the cause of the new illnesses is often a lack of hygiene, malnutrition and thus a weakened immune system . Mutations in the TLR-2 gene can lead to an increased susceptibility to leprosy infections.

The incubation period is unusually long and also depends on the state of the immune system. It lasts at least a few months, on average around five years, but it can also last 20 years or more.

classification

| Classification according to ICD-10 | |

|---|---|

| A30 | Leprosy |

| A30.0 | Indeterminate leprosy |

| A30.1 | Tuberculoid leprosy |

| A30.2 | Borderline tuberculoid leprosy |

| A30.3 | Borderline leprosy |

| A30.4 | Borderline lepromatous leprosy |

| A30.5 | Lepromatous leprosy |

| ICD-10 online (WHO version 2019) | |

The symptoms of leprosy vary greatly from patient to patient. In order to be able to classify the different manifestations, the VI. International Leprosy Congress 1953 in Madrid made the following classification:

- indeterminate leprosy

- tuberculoid leprosy

- Borderline tuberculoid leprosy

- Borderline leprosy

- Borderline lepromatous leprosy

- lepromatous leprosy

Symptoms

In this disease, the nerves die and the blood vessels - arteries and veins - become clogged with a thickening of the blood. Those affected usually lose the feeling of cold, warmth and pain. Without treatment, patients often injure themselves unnoticed and become infected with life-threatening diseases such as B. Tetanus . Hence the idea that leprosy causes fingers, toes, hands or ears to fall off. Because sufferers feel no pain, wounds are often left untreated and inflammation can kill these areas of the body.

Early stage

In the early stages, one speaks of indeterminate or uncharacteristic leprosy. The indeterminate form of leprosy manifests itself in blurred spots ( leprosy ) on the skin. In dark-skinned people these are lighter than healthy skin, in light-skinned people they are reddened. The spots themselves feel numb to the sick person. In this phase the disease can stagnate, heal spontaneously or develop into tuberculoid, lepromatous or borderline leprosy.

Tuberculoid Leprosy (Paucibacilliary Leprosy)

This tuberculoid form of leprosy develops when the body is in a good defensive position and is slower and more benign than lepromatous leprosy. The tuberculoid leprosy is only slightly contagious and rarely mainly affects the nerves and skin, the lymph nodes. Organ involvement does not occur. The patches of skin here are often flat or slightly raised, always sharply delimited and reddish to reddish-purple in color. In contrast to lepromatous leprosy, the distribution of skin changes is asymmetrical. At the beginning there is a hypersensitivity (hyperesthesia) in the area of the skin lesions, in the course the temperature sensation is lost first and later the sensation of touch and pain. The skin loses the ability to form sweat (anhidrosis). The hair falls out in the affected areas. In addition to the skin, the peripheral nerves in particular are knotty and thickened. The infestation is asymmetrical here too. As the disease progresses, the sense of touch continues to decrease until the patient can no longer feel anything. The consequences are often serious injuries and, as a result, further mutilations. The involvement of motor nerves manifests itself in muscle weakness, muscle regression and symptoms of paralysis.

Borderline leprosy

Borderline leprosy , also known as the dimorphic form of leprosy, is an unstable variant of the disease that develops depending on the state of the immune system . If the immune system is largely intact, the low-bacteria, tuberculoid form develops. If the immune system is damaged, the bacteria multiply almost undisturbed. The bacteria-rich, contagious lepromatous form develops. The symptoms in the borderline stage can resemble those of tuberculoid leprosy or show clear deviations. So the skin spots can be symmetrical; the nerves can also be affected symmetrically.

Lepromatous leprosy (multibacillary leprosy)

The lepromatous leprosy is the most severe form of the disease. As the bacteria multiply unchecked, they spread throughout the body via blood vessels, nerve tissue, mucous membranes and the lymphatic system (with the possibility of elephantiasis ). The skin is severely changed and covered with lumps and small spots. Characteristic are the light red to brown lepromes , which decompose the face and other parts of the body. Especially in the face, these merge into a "lion face" ( Facies leonina ). As the disease progresses, it can lead to ulcerative disintegration with involvement of bones, muscles and tendons and the internal organs.

Death does not occur directly from the pathogen, but from secondary infections .

therapy

Basically, leprosy is nowadays considered curable. Almost 16 million patients were treated worldwide between 1995 and 2015.

The first pharmacologically effective therapeutic approaches with chemotherapeutic agents existed at the beginning of the 20th century. In 1916, the chemist Alice Ball found a way to extract the oil of the chaulmoograp plant , which contains a lot of chaulmoogric acid , which could initially be used successfully. However, by the 1930s, the bacteria had developed resistance. A breakthrough in leprosy therapy came in the 1940s with sulfonamide therapy. In 1947 Robert G. Cochrane introduced the antibiotic dapsone (DDS), which is still important today, but only has a bacteriostatic effect .

The healing prospects as well as the appropriate form of therapy depend on the appearance and progress of the disease. A lepromin test is carried out to clarify this . Depending on the diagnosis, combination therapy with the drugs dapsone , clofazimine (since 1962) and the bactericidal rifampicin (since 1971) is the therapy of choice (second-line chemotherapeutic agents are minocycline, clarithromycin and ofloxacin). It happens that a change in the level of immunity leads to a deterioration in the condition. This change is called the leprosy response . The complex processes involved must be treated by a specialist with a therapy that is individually tailored to the patient.

In the 1970s, combination therapies with several antibiotics were developed and successfully tested in a multi-year field trial in Malta. Based on this, the WHO has been recommending polychemotherapy since 1982 (in contrast to the procedure in the United States of America) in a form that has hardly been modified to this day:

- for isolated skin lesions: rifampicin, ofloxacin and minocycline

- for two to five skin lesions: dapsone and rifampicin

- if there are more than five skin lesions: dapsone, rifampicin and clofazimin (or prothionamide)

- for erythema nodosum leprosum: thalidomide or clofazimin

The active ingredient thalidomide is effective in the treatment of erythema nodosum leprosum (ENL) . Due to the harmful side effects during pregnancy on the unborn child ( embryopathy ), strict safety precautions are in place during therapy. As an alternative to thalidomide, clofazimin is used. Although there are still supply problems with the necessary drugs in developing and emerging countries, leprosy was pushed back further in the 1990s. The WHO is working to eradicate this disease.

Preventive measures for leprosy are:

- For paresis and contractures: physiotherapy

- To prevent dehydration of the eyes: eye drops and ointments

- Skin care

- If sensitivity is impaired: Avoid even minor injuries (gloves, padding, insoles, renovation measures in the household, thermal insulation on devices and radiators).

Reporting requirement

In Austria, leprosy is notifiable in the event of suspicion, illness or death in accordance with Section 1 (1) Z1 of the 1950 Epidemic Act . Doctors and laboratories, among others, are obliged to report this ( Section 3 of the Epidemic Act).

In Germany, the detection of the pathogen Mycobacterium leprae by the laboratory etc. must be reported by name (according to Section 7 IfSG).

Museums

In Germany there is the Leprosy Museum in Münster .

In Norway, there is also a leprosy museum in the city of Bergen , where there was a leprosy hospital that was headed by DC Danielssen.

The Leprosenhaus (Bad Wurzach) is a preserved infirmary for lepers, but it does not show an exhibition on the subject.

World Leprosy Day

World Leprosy Day has been celebrated on the last Sunday in January since 1954 . It was initiated in 1954 by Raoul Follereau . It was equated with the day of death of Mahatma Gandhi , who had campaigned for lepers throughout his life.

literature

- Marianne Abele-Horn: Antimicrobial Therapy. Decision support for the treatment and prophylaxis of infectious diseases. With the collaboration of Werner Heinz, Hartwig Klinker, Johann Schurz and August Stich. 2nd, revised and expanded edition. Peter Wiehl, Marburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-927219-14-4 , pp. 207-209.

- Andreas Kalk: Leprosy in Central Asia: The almost forgotten disease . In: Deutsches Ärzteblatt . tape 97 , no. 13 . Deutscher Ärzte-Verlag , March 31, 2000, p. A-829 / B-714 / C-650 .

- Anna Bergmann: Fatal human experiments in colonial areas. The leprosy research of the doctor Eduard Arning in Hawaii 1883–1886. In: Ulrich van der Heyden, Joachim Zeller (ed.) "... Power and share in world domination." Berlin and German colonialism. Unrast-Verlag, Münster 2005, ISBN 3-89771-024-2 .

- Friedrich Bühler: The leprosy in Switzerland (= medical-historical studies. 1). Zurich 1902.

- Luke Demaitre: Leprosy in Premodern Medicine: A Malady of the Whole Body. The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore 2007, ISBN 978-0-8018-8613-3 .

- Rod Edmond: Leprosy and Empire: A Medical and Cultural History. Cambridge 2007, ISBN 978-0-521-86584-5 .

- Dietrich von Engelhardt : Representation and interpretation of the leprosy in the newer literature. In: Jörn Henning Wolf (ed.): Leprosy, leprosy, Hansen's disease. A changing human problem. Part II: Articles (= catalogs of the German Museum of Medical History. Supplement 1). Würzburg 1986, ISBN 3-926454-00-8 , pp. 309-320.

- Philipp Gabriel Hensler : On occidental leprosy in the Middle Ages, along with a contribution to the knowledge and history of leprosy. Herold Brothers, Hamburg 1790 ( digitized version of the Bavarian State Library ; reprint, Bachmann and Gundermann, Hamburg 1794).

- Gundolf Keil : Leprosy. In: Lexicon of the Middle Ages . Volume 1, 1978, Col. 1249-1257.

- Gundolf Keil: Leprosy (leprosy, Hansen's disease). and leprosy texts. In: Werner E. Gerabek , Bernhard D. Haage, Gundolf Keil, Wolfgang Wegner (eds.): Enzyklopädie Medizingeschichte. De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2005, ISBN 3-11-015714-4 , pp. 841-845.

- Huldrych M. Koelbing , Monica Schär-Send, Antoinette Stettler-Schär, Hans Trümpy: Contributions to the history of leprosy (= Zurich medical historical treatises, new series. Volume 92). Zurich 1972, ISBN 3-260-03380-7 .

- Ernest Persoons (ed.): Lepra in de Nederlanden (12de – 18de eeuw) (= Algemeen rijksarchief en rijksarchief in de provinciën: educatieve dienst dossiers. II, 3). Brussels 1989.

- Horst Müller-Bütow: Leprosy. An overview of medical history with a special focus on medieval Arabic medicine. Philosophical dissertation Saarbrücken (Saarland University). Frankfurt am Main 1981.

- Christa Habrich , Juliane C. Wilmanns , Jörn H. Wolf , Felix Brandt (eds.): Leprosy, leprosy, Hansen's disease. Part I: Catalog. Munich 1982 (= catalogs of the German Medical History Museum. Volume 4).

- Jörn Henning Wolf (Ed.): Leprosy, leprosy, Hansen's disease. A changing human problem. Part II: Articles (= catalogs of the German Museum of Medical History. Supplement 1). Würzburg 1986, ISBN 3-926454-00-8 .

- about: Georg Sticker: Leprosy and syphilis around the year 1000 in the Middle East. In: Janus. 28, 1924, p. 394.

- Karl Friedrich Schaller: The Leprosy Clinic. In: Jörn Henning Wolf (ed.): Leprosy, leprosy, Hansen's disease. A changing human problem. Part II: Essays. Würzburg, 1986, pp. 17-26.

- A. Schelberg: Lepers in medieval society . (PDF; 2.50 MB) Dissertation, Göttingen 2000.

- Alois Paweletz: Leprosy diagnostics in the Middle Ages and instructions for leprosy show . Medical dissertation. Leipzig 1915; archive.org .

- Evelyne Leandro: Suspended. The struggle with a long-forgotten disease. A diary from today's Berlin. Create Speace, 2014, ISBN 978-1-5029-7997-1 .

- Ortrun Riha : Leprosy as a metaphor. From the story of a social illness. In: Dominik Groß , Monika Reiniger: Medicine in History, Philology and Ethnology. Festschrift for Gundolf Keil. Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2003, ISBN 3-8260-2176-2 , pp. 89-105.

- Leo van Bergen: Uncertainty, Anxiety, Frugality. Dealing with Leprosy in the Dutch Indies 1816-1942 . NUS Press, Singapore, ISBN 978-981-4722-83-4 .

- Heinrich Martius (medic, 1781) : De lepra taurica. Dissertation. Stabitz, Leipzig 1816, OCLC 1071267361 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ).

- Karl Wurm, AM Walter: Infectious Diseases. In: Ludwig Heilmeyer (Hrsg.): Textbook of internal medicine. Springer-Verlag, Berlin / Göttingen / Heidelberg 1955; 2nd edition, ibid. 1961, pp. 9-223, here: pp. 221-223.

Web links

- Leprosy - information from the Robert Koch Institute

- Leprosy Today - WHO Leprosy Program

Individual evidence

- ↑ Leprosy. In: Dictionary of Origin. Dudenverlag, Mannheim 2007.

- ↑ Hans Trümpy: The lepers in medieval society. In: Huldrych M. Koelbing, Monica Schär-Send, Antoinette Stettler-Schär, Hans Trümpy (eds.): Contributions to the history of leprosy (= Zurich medical historical treatises, new series. Volume 92). Zurich 1972, ISBN 3-260-03380-7 , pp. 84–92, here: p. 84.

- ↑ Leprosy. In: Dictionary of Origin. Dudenverlag, Mannheim 2007.

- ↑ Gundolf Keil: The leprosy in the Middle Ages. In: Jörn Henning Wolf (ed.): Leprosy, leprosy, Hansen's disease. A changing human problem. Part II: Articles (= catalogs of the German Medical History Museum. Supplement 1). German Leper Aid Organization, Würzburg 1986 (1987), pp. 85-103, here: p. 94.

- ↑ Ortrun Riha: Leprosy as a metaphor. From the story of a social illness. 2003, p. 89 f.

- ↑ Märta Åsdahl-Holmberg: The German synonym for 'leper' and 'leprosy'. In: Low German messages. Volume 26, 1970, pp. 25-71.

- ↑ Benedikt Ignatzek: From the history of dermatology. In: Würzburger medical history reports , Volume 23, 2004, pp. 524–527, here p. 524.

- ↑ a b Zaraat. In: Meyers Großes Konversations-Lexikon . 6th edition. Volume 20, Bibliographisches Institut, Leipzig / Vienna 1909, p. 854 . "Zaraat, as much as leprosy."

- ↑ The meaning of Zaraat. Chabad-Lubavitch Media Center, accessed June 25, 2014 .

- ↑ Leprosy. In: Friedrich Kluge: Etymological dictionary of the German language. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 1975.

- ↑ Stefan Winkle: Scourges of humanity. Artemis and Winkler, 1997, ISBN 3-538-07049-0 .

- ↑ Skeleton find: Leprosy plagued humanity 4,000 years ago. In: Spiegel Online . May 27, 2009. Retrieved December 28, 2014 .

- ↑ Leprosy - Leuke among the Greeks. In: Meyers Großes Konversations-Lexikon. Retrieved June 25, 2014 .

- ^ Gundolf Keil: Leprosy (leprosy, Hansen's disease). In: Werner E. Gerabek , Bernhard D. Haage, Gundolf Keil, Wolfgang Wegner (eds.): Enzyklopädie Medizingeschichte. De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2005, ISBN 3-11-015714-4 , pp. 841-844, here: p. 841.

- ↑ Horst Kremling : Historical considerations on preventive medicine. In: Würzburg medical history reports. Volume 24, 2005, pp. 222-260, here: pp. 227 f.

- ^ Gundolf Keil: Leprosy (leprosy, Hansen's disease). 2005, p. 841.

- ↑ Otto Betz : The leprosy in the Bible. In: Jörn Henning Wolf (ed.): Leprosy, leprosy, Hansen's disease. A changing human problem. Part II: Essays. Würzburg 1986, pp. 45-62.

- ↑ Verena J. Schuenemann, Charlotte Avanzi, Ben Krause-Kyora, Alexander Seitz, Alexander Herbig, Sarah Inskip, Marion Bonazzi, Ella Reiter, Christian Urban, Dorthe Dangvard Pedersen, G. Michael Taylor, Pushpendra Singh, Graham R. Stewart, Petr Velemínský, Jakub Likovsky, Antónia Marcsik, Erika Molnár, György Pálfi, Valentina Mariotti, Alessandro Riga, M. Giovanna Belcastro, Jesper L. Boldsen, Almut Nebel, Simon Mays, Helen D. Donoghue, Sonia Zakrzewski, Andrej Benjak, Kay Nieselt, Stewart T. Cole , Johannes Krause : Ancient genomes reveal a high diversity of Mycobacterium leprae in medieval Europe. In: PLOS. , May 10, 2018 (online)

- ↑ Gundolf Keil: Introduction. In: Gundolf Keil (Ed.): The Lorsch Pharmacopoeia. (Manuscript Msc. Med. 1 of the Bamberg State Library); Volume 2: Translation by Ulrich Stoll and Gundolf Keil with the assistance of former abbot Albert Ohlmeyer . Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft, Stuttgart 1989, pp. 7-14, here: p. 14.

- ^ Werner Kloos: Bremer Lexikon. Hauschild, Bremen 1980, Lemma Leprosenhaus.

- ↑ see: Entry on Sankt Jost - wayside shrine (wayside shrine between Biewer and Pallien) in the database of cultural assets in the Trier region ; accessed on September 15, 2015. and Karl Duerr. In: karlduerr.de. December 22, 2003, accessed December 28, 2014 .

- ↑ Stefan Winkle: Scourges of humanity. 1997.

- ↑ Alois Paweletz: Leprosy Diagnostics in the Middle Ages and Instructions for Leprosy Show. Medical dissertation Leipzig, Leipzig 1915.

- ↑ Gundolf Keil: Leprash texts. In: Werner E. Gerabek et al. (Ed.): Encyclopedia Medical History. 2005, p. 844 f.

- ↑ Norbert H. Ott: Miselsuht - Leprosy as a topic of narrative literature in the Middle Ages. In: Jörn Henning Wolf (ed.): Leprosy, leprosy, Hansen's disease. A changing human problem. Part II: Essays. Würzburg 1986, pp. 273-283.

- ↑ Armin Hohlweg: On the history of leprosy in Byzantium. In: Jörn Henning Wolf (ed.): Leprosy, leprosy, Hansen's disease. A changing human problem. Part II: Essays. Würzburg 1986, pp. 69-78, here: p. 71.

- ↑ Konrad von Würzburg: Engelhard (= Old German Text Library, 7 ). Edited by Ingo Reiffenstein, 3rd edition. Tübingen 1982, verses 5144-5171.

- ↑ Antoinette Stettler-Schär: Leprology in the Middle Ages and in the early modern period. In: Huldrych M. Koelbing, Monica Schär-Send, Antoinette Stettler-Schär, Hans Trümpy (eds.): Contributions to the history of leprosy (= Zurich medical historical treatises, new series. Volume 92). Zurich 1972, pp. 55-93.

- ↑ Antoinette Stettler-Schär: Leprology in the Middle Ages and in the early modern period. 1972, p. 71.

- ^ Gundolf Keil, Friedrich Lenhardt: Lepraschau texts. In: Author's Lexicon . 2nd Edition. Volume 5, Col. 723-726.

- ↑ Rainer Sutterer: Anton Trutmanns Pharmacopoeia '. Part I: Text. Medical dissertation, Bonn 1976, pp. 35-46 and 227-230.

- ↑ Leprosy. In: Meyers Großes Konversations-Lexikon. Volume 2. 6th edition, Leipzig / Vienna 1905, pp. 148–149.

- ^ Günter Petersen: The skin and its diseases in science, culture and history . Lit-Verlag, Berlin 2019, ISBN 978-3-643-14321-1 , pp. 87 .

- ^ Leprosy home in Memel (GenWiki)

- ↑ Kurt Schneider: The occurrence of leprosy in the district of Memel and the German leprosy home near Memel 1899 to 1945. In: Joachim Hensel (Ed.): Medicine in and from East Prussia. Reprints from the circulars of the "East Prussian Medical Family" 1945–1995. Bockhorn 1996, ISBN 3-00-000492-0 , pp. 409-410.

- ^ Albrecht Scholz: Boeck, Carl Wilhelm. In: Werner E. Gerabek , Bernhard D. Haage, Gundolf Keil , Wolfgang Wegner (eds.): Enzyklopädie Medizingeschichte. De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2005, ISBN 3-11-015714-4 , p. 197.

- ↑ Koizumi apologises for leper colonies BBC News, May 25, 2001 (English)

- ↑ 療養 所 に つ い て. (No longer available online.) In: eonet.ne.jp. Archived from the original on June 23, 2009 ; Retrieved October 9, 2012 (Japanese).

- ^ A b Susan Burns: Rethinking 'Leprosy Prevention'… In: Journal of Japanese Studies. Vol. 38, 2012, pp. 297-323.

- ^ H. Feldmeier: Leprosy. In: Hans Schadewaldt (Ed.): About the return of epidemics. 1996, OCLC 1106411757 , p. 48.

- ↑ Ioannis D. Bassukas, Georgios Gaitanis, Max Hundiker: Leprosy and the natural selection for psoriasis. In: Medical Hypotheses . Volume 78, number 1, January 2012, pp. 183-190, doi: 10.1016 / j.mehy.2011.10.022 . PMID 22079652 .

- ^ B. Krause-Kyora et al .: Ancient DNA study reveals HLA susceptibility locus for leprosy in medieval Europeans. In: Nature Communications. 2018. doi: 10.1038 / s41467-018-03857-x

- ^ Leprosy Mission. In: lepramission.ch. Retrieved December 28, 2014 .

- ^ Daniel Gerber: Medication guaranteed until 2020 - Leprosy Mission and Novartis are going the “tough last mile”. livenet.ch, July 19, 2012, accessed on September 1, 2012 .

- ↑ Ashok Moloo: Leprosy: new data show steady decline in new cases. In: Neglected tropical diseases> Leprosy (Hansen's disease). WHO , September 9, 2019, accessed May 23, 2020 .

- ↑ a b c d Global leprosy (Hansen disease) update, 2019: time to step-up prevention initiatives . In: World Health Organization (Ed.): Weekly epidemiological record . tape 95 , no. 36 , September 4, 2020, p. 417-440 ( who.int [PDF]).

- ↑ a b Global leprosy (Hansen disease) update, 2020: impact of COVID-19 on global leprosy control . In: World Health Organization (Ed.): Weekly epidemiological record . tape 96 , no. 36 , September 10, 2021, p. 421-444 ( who.int [PDF]).

- ↑ Andreas Kalk: The almost forgotten disease. In: Deutsches Ärzteblatt. 97/13, 2000, pp. B-714-B-715.

- ^ Pedro Simón: La última leprosería de España. In: El Mundo, Fontilles (Alicante). El Mundo, January 31, 2016, accessed May 23, 2020 (Spanish).

- ↑ ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Biozentrum, University of Basel

- ↑ Pushpendra Singh et al .: Insight into the evolution and origin of leprosy bacilli from the genome sequence of Mycobacterium lepromatosis. In: PNAS . Volume 112, No. 14, 2015, pp. 4459-4464, doi: 10.1073 / pnas.1421504112

- ↑ a b c Leprosy. Fact sheet. In: WHO Health Topics> Leprosy (Hansen's disease)> Fact Sheets. World Health Organization WHO, September 10, 2019, accessed November 26, 2020 .

- ↑ UniProt O60603

- ↑ Profiles of rare and imported infectious diseases . ( Memento from July 17, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF) Robert Koch Institute (2011) p. 74.

- ↑ O. Braun-Falco: Dermatology and Venereology. Springer Verlag, 2005.

- ↑ Huldrych M. Koelbing , Antoinette Stettler-Schär: Leprosy, Leprosy, Elephantiasis Graecorum. On the history of leprosy in antiquity. In: Huldrych M. Koelbing, Monica Schär-Send, Antoinette Stettler-Schär, Hans Trümpy (eds.): Contributions to the history of leprosy (= Zurich medical historical treatises, new series. Volume 92). Zurich 1972, pp. 34–54.

- ^ Jeannette Brown: African American Women Chemists. Oxford University Press, 2011, ISBN 978-0-19-991272-8 , p. 178. Limited preview in Google Book Search

- ↑ Paul Wermager, Carl Heltzel: Alice A. Augusta ball . In: ChemMatters . tape 25 , no. 1 , February 2007, p. 16–19 ( pbworks.com [PDF; accessed April 2, 2016]).

- ↑ Christina Hohmann: The "punishment of God" is curable. In: Pharmaceutical newspaper online. GOVI-Verlag, 2002, accessed on December 4, 2013 .

- ↑ Marianne Abele-Horn: Antimicrobial Therapy. Decision support for the treatment and prophylaxis of infectious diseases. With the collaboration of Werner Heinz, Hartwig Klinker, Johann Schurz and August Stich. 2nd, revised and expanded edition. Peter Wiehl, Marburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-927219-14-4 , p. 207.

- ↑ a b Marianne Abele-Horn (2009), p. 208.

- ↑ Eckart Roloff, Karin Henke-Wendt: The leprosy brought exclusion and social death (The Leprosy Museum in Münster-Kinderhaus). In: Visit your doctor or pharmacist. A tour through Germany's museums for medicine and pharmacy. Volume 1: Northern Germany. S. Hirzel Verlag, Stuttgart 2015, ISBN 978-3-7776-2510-2 , pp. 144-146.

- ^ The Leprosy Museum - St. Jørgen Hospital. Retrieved April 2, 2016 .

- ↑ Eckart Roloff , Karin Henke-Wendt: Krücken, Klappern and a painter named Mahler (Das Leprosenhaus Bad Wurzach). In: Visit your doctor or pharmacist. A tour through Germany's museums for medicine and pharmacy. Volume 2: Southern Germany. S. Hirzel Verlag, Stuttgart 2015, ISBN 978-3-7776-2511-9 , pp. 30-32.

- ^ World Leprosy Day. Time and Date. Accessed January 30, 2020.