Beatrix Potter

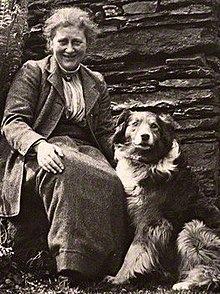

Helen Beatrix Potter (born July 28, 1866 in London , † December 22, 1943 in Sawrey , Lancashire , England ) was an English children's author and illustrator. She started working as an illustrator in 1890. Your children's books have been and are very successful; Stories like her best-known work, The Story of Peter Hase, are published to this day.

For a long time, Beatrix Potter was forced to lead the conventional life of an upper-middle-class woman. She was brought up exclusively by governesses and private tutors, lived in the house of her wealthy parents until she was three years old and only had her own financial means thanks to her drawings. At the age of 28, she embarked on a long trip, during which she was not accompanied by a parent or governess for the first time. At the age of 39, against the determined opposition of her parents, she became engaged to the publisher Norman Warne. He died of leukemia shortly after the engagement .

Thanks to the income from her work, she was finally able to fulfill her desire to acquire extensive land holdings in the Lake District , where she established herself as a successful breeder of Herdwick sheep. She became increasingly committed to the preservation of the characteristic features of this region and bequeathed her land holdings of around 16 square kilometers to the National Trust.

Life

Family background

Beatrix Potter was born in London, but in the second half of her life it was very important that her roots lay in the rural north of England. "My brother & I were only born in London because my father was a lawyer there," she later wrote. In fact, both her maternal and paternal families came from the Manchester area. Her paternal grandfather, Edmund Potter, had successfully built a company there with his cousin Charles Potter that produced printed cotton fabrics. The company went bankrupt when consumer tastes changed and a tax made printed cotton fabrics more expensive. Edmund Potter succeeded in building a second company through improved technology, which also produced printed cotton fabrics. So remarkable was his innovations that they were shown during the Great London Industrial Exhibition of 1851 and Edmund Potter was elected a member of the Royal Society in 1856 . In 1862 Edmund Potter & Company was the largest cotton printing company in the world. In the same year Edmund Potter was elected to the British Parliament as a Liberal; the management of the company was taken over by his eldest son.

Beatrix Potter's maternal grandfather, John Leech, was no less economically successful and owned cloth mills in the Manchester area. He died in 1861 and bequeathed a large dowry of 50,000 pounds sterling to each of his daughters. Both families were united by the fact that they adhered to Unitarianism , a belief system that had developed from the anti-Trinitarianism of the radical Reformation . The families were closely intertwined. Two sons of Edmund Potter married daughters of John Leech.

Born in 1832, Rupert Potter, Beatrix Potter's father, was the second oldest surviving son of Edmund Potter. As is increasingly common for wealthy families of the English upper class, he studied law and was admitted to the bar in 1857. There are very few documents to prove his practice as a lawyer. However, there is much to suggest that he specialized in property transfers. The few evidence that he has received to prove that he was a lawyer is sometimes interpreted to mean that he was not very active as a lawyer. Beatrix Potter's biographer, Linda Lear, argues, however, that this form of legal activity basically leaves little evidence, and since Rupert Potter only received his inheritance in 1884, one can safely assume that he was active as a lawyer in London for a long time. It is undisputed, however, that Rupert Potter was an extremely wealthy man from the beginning of the 1890s, who received most of his income from investments.

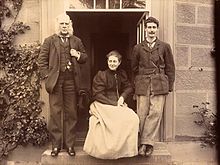

On August 8, 1863, Rupert Potter married Helen Leech. Very little is known about their childhood and upbringing. Although not verifiable, given her social background, it is most likely that she was raised by governesses and thus probably only enjoyed a very superficial upbringing. There is a body of evidence that both Rupert and Helen Potter were keen on social acceptance. Rupert Potter joined the prestigious Reform Club shortly after he was admitted to the bar, presumably benefiting from his father being a well-known Liberal MP. In 1860 he was proposed as a member of the renowned Athenaeum Club and was accepted in 1874. As a follower of Unitarianism - and unmistakably Northern England due to its dialect - his opportunities for advancement in London society were limited. However, in keeping with the habits of their shift, Rupert and Helen Potter gave numerous receptions at their London home and spent the off-season in the country.

Childhood and youth

childhood

Beatrix Potter was born in House No. 2, Bolton Gardens, London-Kensington . Her parents had moved to this rural part of London when Helen Potter was pregnant. Bolton Gardens was a relatively new settlement and, like the Potters, the population consisted almost entirely of upper-middle-class families. The four-story houses had a small garden in front and a large garden behind the house. The house also had stables for the carriage horses and living space for the coachman. The staff included a cook and a housekeeper, a butler, a coachman and a groom. The Scottish Calvinist Ann Mackenzie was hired as the nanny for Beatrix Potter .

Linda Lear points out that Beatrix Potter's childhood is often described as oppressive, isolated, and monotonous. It is true that, measured by the number of friendships Beatrix Potter made during her childhood, or even just the opportunities to meet children of the same age, her childhood was lonely and limited. As is typical of girls of her age and social class, Beatrix Potter was raised exclusively at home. Her close bond with her brother Walter "Bertie" Bertram, who was born in March 1872, is certainly a reaction to her rare encounters with other children. At the same time, Beatrix Potter's childhood was a very privileged one. Due to the interests of her family, she had an unusually high degree of access to art, literature and science and had traveled widely for her time. Much of her childhood was spent on Camfield Place, her paternal grandparents' lavish country estate. The Potters also spent long summer months from 1871 to 1881 at Dalguise House, rented by their father, in Perthshire , Scotland, where numerous friends of their parents were guests. These included William Gaskell, the father of the writer Elizabeth Gaskell , and the well-known painter John Everett Millais and his wife Effie Gray .

At the age of about six, Beatrix Potter's upbringing was entrusted to governess Florrie Hammond, with whom Potter developed a close bond. Hammond remained in the Potter's household until 1883 when Beatrix was nearly 17 years old and Bertram was sent to boarding school. In addition to reading, writing and arithmetic, Beatrix Potter also received lessons in Latin and was also taught French by dedicated teachers. Beatrix Potter's enthusiasm - and her talent - for drawing was evident early on and was encouraged by both parents. Her earliest sketchbook, entitled Dalguise 1875 , shows careful watercolor studies of caterpillars. Each page is divided into two columns. One describes the appearance, in the second observations of their habits were recorded. In addition, Beatrix Potter and her brother were allowed to keep an unusually large menagerie of pets. Among other things, they had dogs, kept mice, frogs, lizards and newts as well as rabbits. Bertram also tended bats, a kestrel and a jay. Most of these animals were also drawn by Beatrix Potter. Because of her obvious talent, her governess recommended that her parents hire an additional drawing teacher in 1878, and Beatrix took drawing and painting lessons from a Miss Cameron for the next five years. Occasionally Beatrix also accompanied her father on visits to his friend Millais' studio. Millais encouraged them in their attempts at drawing. As she noted in her diary in 1884, he commented on her work with the words “Lots of people can draw, but you and my son John watch her.” Her father, who was an avid photographer, also taught her photography.

Towards the end of her time with her drawing teacher Cameron, Rupert Potter sought advice from friends on how he could further develop his talented daughter. Advice included Lady Elizabeth Eastlake , a well-known art critic and widow of the director of the National Gallery . Beatrix Potter then received lessons in oil painting from a previously unidentified artist in 1883. The tuition was expensive, and after her third lesson, she noted in her diary that she did not appreciate the tuition. Above all, she was concerned that working with oil paints could harm her very developed watercolor technique. Her parents took her to visit galleries and art exhibitions. William Turner was one of the painters who made a lasting impression on her. An art exhibition with old masters, including Joshua Reynolds , Thomas Gainsborough and Anthonis van Dyck , made a lasting impression on her.

When Florrie Hammond gave up her governess position in the spring of 1883, it would have been acceptable under the conventions of the time not to hire another governess for Potter. That was certainly Potter's hope, who noted in her diary that she had long since wanted nothing more than to concentrate exclusively on her painting. Without consulting her daughter, however, Hellen Leech hired Annie Carter as governess and companion for Potter. The decision created considerable tension with her daughter. In fact, a good relationship soon developed between Potter and Annie Carter. Carter was only three years older than Potter, but had led a much less sheltered life than Potter and lived in Germany, among other places. She taught Potter in German and Latin, with Potter developing a preference for the latter language in particular.

Summer stays in the Lake District

Rupert Potter decided in the spring of 1882 not to continue the summer stays in Dalguise any longer. Instead, he rented Wray Castle on the northernmost tip of Lancashire for the summer months. There the Potters met the then 26-year-old local parish vicar Hardwicke Drummond Rawnsley know. Rawnsley, who had first worked as a pastor of the poor in Bristol, had been transferred here after the pastor's position became vacant and was deeply impressed by the landscape of the Lake District. Rawnsley was well read and was a student at Balliol College with influential art critic John Ruskin . After graduating, he worked with the social reformer Octavia Hill in the slums of London. This work experience had led him to firmly believe that open, wide landscapes, parks and clean air were among the basic rights of even the poorest urban population. He developed a special bond with the landscape of the Lake District. In 1895 he co-founded the National Trust to help protect this landscape.

Rupert Potter was taken with the young priest, who - like him - was passionate about photography. Rawnsley, who had just returned from a sabbatical in Egypt, the Sinai, and Palestine, had already published two books, was working on an inventory of the excavations of a Roman villa, and had written the first of his writings on the culture of the Lake District. A special relationship also developed between Beatrix Potter and the pastor. He was one of those people who quickly recognized her particular artistic talent, and he took the time to hold regular dialogues with her about the natural history, geology, and archeology of the Lake District. The deep affection for this part of Great Britain and its inhabitants, which shaped Beatrix Potter's adult life, is largely shaped by the encounter with Hardwicke Rawnsley.

Early adult life

In the Victorian Age , young women were deemed to have completed their education when they reached the age of 17 or 18. Members of the wealthier strata of the population were then either introduced at court or introduced into society in another form. This was followed by a phase of life that in wealthy families was characterized by a lot of idleness, the performance of representative duties and extended visits to relatives until they married themselves. Beatrix Potter's life as a young woman shows all of these characteristics. Her entry into adult life marked a big celebration on the occasion of her 19th birthday. It was the first birthday party in ten years, and Potter wrote in her diary that she hoped it would last for the next ten years. More than 100 guests were invited and even according to Potter's assessment, the celebration was a success: "I had fun, and contrary to what I and my parents expected, I also behaved well." A little later, Annie Carter finished her task as governess of Beatrix Potter. She left the Potters' house to marry an engineer a little later. Beatrix stayed in contact with her even when she gave birth to her first children. At the end of her assignment, Potter noted in her diary:

“By and large, I liked my last governess the most of all - Miss Carter had her faults and was one of the youngest people I have ever met, but she was good-natured and intelligent. ... The rules of geography and grammar are tiresome, but there is no word with which I can express the feelings I have always harbored for arithmetic. "

Beatrix Potter's early adult life was also shaped by the fact that her brother was mostly absent - because he was first sent to boarding school, then traveled to continental Europe and finally studied. Diary entries like the one at the end of 1895 suggest that this was accompanied by an almost unbearable boredom for Beatrix Potter. At the same time, the social position of her family was marginalized by the successes of other family members of the sprawling Potter clan. Her uncle Henry Enfield Roscoe was not only ennobled, but won a seat in parliament as a member of the Liberals. Rupert Potter's younger sister Lucy received an award from the Photographic Society of London and one of her photographs even appeared in a US publication. She was significantly more successful than her brother, who was also very ambitious. At the same time Beatrix Potter was ailing. She suffered from constant exhaustion, often accompanied by increased body temperature. Although the disease was never diagnosed, Potter's biographer Lear thinks it likely that she suffered from a rheumatic fever. The convention of the time gave Beatrix Potter few opportunities to shape her own life. Financially she was completely dependent on her parents and it was not until 1894 - at the age of 28 - that Potter went on a long trip for the first time without a parent. This trip, too, almost failed because of the ban imposed by the mother, who was convinced that her daughter was physically unable to take a train journey alone.

Cramped life and limited marriage market

The very cramped life Beatrix Potter led was not entirely atypical for young, unmarried women of her class. To make matters worse, however, there were repeated conflicts with her mother, which in an unforeseeable way also restricted her daughter's smaller freedoms - for example, by not allowing her to use the carriage or by preventing her cousins from visiting longer with the pretext that Guest bedrooms are not in good condition. In her diaries for 1894, Potter described her mother as "the enemy". Potter's insomnia and her recurring bouts of depression are also a result of these constant conflicts, Lear said.

Beatrix Potter was shy and reserved around strangers or in company. Her father's attempts to introduce her to potential marriage candidates met with little appreciation. It was also difficult to find suitable marriage candidates: the social circle in which the Potters moved in London was largely limited to the small number of families who - like the Potter family - belonged to the Unitarians. Beatrix's mother Helen also had particularly high demands on a suitable marriage candidate for her daughter, who had to expect a considerable dowry: It should be someone with a respected family name who either already inherited property or had the prospect of acquiring it. Potter's biographer believes that she was aware of how limited her chances of a parent-approved marriage were and that this was a key driver in seeking success in the artistic field.

First successes as a draftsman of greeting cards

Henry Enfield Roscoe, who - since his election to the British Parliament - frequented the Potters' house, gave the impetus to try to sell Beatrix Potter's tickets. At Easter 1890, Beatrix Potter had drawn a set of six greeting cards that she sent to five publishers - but received them back immediately. Bertie Potter, who was living with his parents at the time to prepare for the entrance exam for Oxford, then personally brought the six cards to the greeting card publisher Hildesheimer & Faulkner . The very next day Beatrix Potter received a check for six pounds from this company and a request to the "gentleman artist" to submit further sketches. The drawings appeared as greeting cards at Christmas 1890 and as illustrations of a book of poetry A Happy Pair by Frederic E. Weatherly.

Roscoe also accompanied his niece to her first business meeting with her publisher: According to Potter's diary entries, her uncle largely left the negotiation to her. At this meeting, Potter wanted to find out what motives her publisher was interested in. She later stated critically that he had shown more interest in humorous drawings than in the artistry of execution. At the same time, however, it was Faulkner who first expressed the idea of telling a story for children by drawing and marketing it as a book. However, the business relationships with Hildesheimer & Faulkner did not prevent Potter from making contact with other publishers.

Natural history work

Interest in natural history subjects was widespread in the Victorian era. Aquariums had become popular since the mid-19th century . Numerous women of the classes that social conventions obligated themselves to idleness devoted themselves to the study of insects, shells, ferns, fossils and mushrooms. According to her biographer Lear, the first motive for Beatrix Potter to deal with it was the escape from the boredom of her life. The combination of her observation and artistic talent enabled her to be more successful in this field than most of her contemporaries who pursued the same hobby. She found support from her parents, and her brother gave her his microscope. The oldest watercolors, which are evidence of this hobby, were created towards the end of the 1880s and show mushrooms - Herbst-Lorchel , Semmel-Stoppelpilz , Real Chanterelle , Violet Rötelritterling and Common Waldfreund-Rübling . Her knowledge was so detailed that, during a stay in Scotland in 1893, she was also able to identify the common curly-headed boletus , which is extremely rare in Scotland , and record it in three drawings. The occurrence of this type of fungus was only proven in Scotland in 1889. Potter drew fossils or conspicuous geological formations with similar enthusiasm. She also received professional recognition for her work: Towards the end of 1895, the director of the Morley Memorial College for Working Men and Women asked her to make twelve entomological lithographs that were to be used for a series of lectures.

With the help of her uncle Roscoe, she managed to obtain a study card for the herbarium of the Royal Botanic Gardens in Kew. This gave her the opportunity to interact with George Edward Massee , a botanist who specialized in mushrooms. Under the influence of Massee - who, however, was skeptical of her attempts - she wrote a paper on the germination of spores . This was presented to the Linnean Society of London by her uncle, Sir Henry Enfield Roscoe , in 1897 , as women were not admitted to the meetings; In 1997 the company issued an apology to this effect.

In addition, she was one of the first to recognize that lichens are a symbiotic system between algae and fungi. Since drawings were the only way to record microscopic observations at the time, she made numerous drawings of algae and mushrooms and was widely recognized as a mushroom expert. Potter's approx. 270 detailed illustrations in watercolor were completed in 1901 and are in the Armitt Library in Ambleside . They are considered to be so detailed that they are still used today to identify mushrooms.

Children's book author

Beginnings

During the 1890s, Potter focused on natural history illustration; her first children's books were not published until the beginning of the 20th century. However, the beginnings of this work go back to the early 1890s. Potter wrote picture letters to children of her wider family as well as to the children of her former governess. In doing so, she unconsciously practiced learning a connection between text and visual implementation that can fascinate children. Mostly she picked up on brief moments that she had observed: a cat trying to catch two fish; a donkey with an apron blindfolded so that it can be taken onto a ferry; the dancing dogs of a circus. A letter to a child suffering from mumps , in which she explains that she cannot visit it because of the risk of infection, is accompanied by a drawing of a woman running away, which is accompanied by a small group of "mumps" - grotesque figures with short legs and swollen ones Heads - is pursued. On September 4, 1893, in a letter that the 27-year-old Beatrix Potter wrote to the five-year-old Noel Moore - son of her former governess - the figure of Peter Rabbit (in English "Peter Rabbit") appears for the first time: "I know not what to write - and so I'll tell you the story of four little rabbits. ”The hero of the story was Potter's own rabbit, Peter. Another letter from Potter to Noel Moore followed the next day, in which she told him the story of the frog Jeremias Wheal. Both Peter Rabbit and the frog Jeremias Quaddel (in English "Jeremy Fisher") are characters who play a major role in Potter's later children's books.

The story of Peter Hase

At the beginning of 1900, her former governess Annie Moore suggested that the picture letters that the Moore children had received from Potter over the years should be processed into a children's book. All of her letters had been saved and loaned to Beatrix Potter so that she could find inspiration for a suitable story. She decided on the story of Peter Hase. The story told in the letter from 1892 was too short, however, so that it had to expand the plot and add more drawings. The six publishers to whom she sent inspection copies all turned them down. Some wanted more color illustrations, others wanted text in poetry. However, Potter had precise ideas about what form “her” children's book should have and how high the price should be at which it should go on sale. She decided to initially have Peter Hase's story printed for her own account. On December 16, 1901, the book appeared for the first time in an edition of 250 copies, most of which the author gave away.

The publisher Frederick Warne & Company was one of those who initially responded negatively to Potter's inspection copies, but then decided to change. There was a lack of works in the publishing program that could compete on the increasingly commercially interesting children's book market. The negotiations with Beatrix Potter were tough - she wanted the book to be available on the market as cheaply as possible, which is why she accepted only receiving a fee of 20 British pounds for the initially planned 5000 copies. More important to her was the copyright in later editions - if Frederick Warne & Company did not reprint the book, they wanted to be able to sell the rights to another publisher. The negotiations were made more difficult by the fact that in 1902, as an unmarried woman, despite her 35 years of age, Potter had only limited legal capacity. She could not sign a contract without her father's consent. There is no definite evidence that Rupert Potter accompanied his daughter to the publisher's office to review the final version of the contract. However, a letter has been received from Beatrix Potter to her publisher in which she apologizes in advance for the fact that her father was occasionally difficult.

On October 2, 1902, The Story of Peter Hase finally appeared . The publisher had increased the number of the first edition from 5,000 to 8,000 copies, which had already been sold before the book was available in stores. By the end of the year, more than 28,000 copies had been printed, and a year after they were first published, the number of Peter Hase books sold was 56,470. Frederick Warne & Company made the mistake of not obtaining copyright in the United States. Pirated editions appeared there in 1903, while the publisher continued cooperation with Beatrix Potter and The Story of Squirrel Nutkin (English title. The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin ) brought out.

Her small-format books (approx. 10 × 14 cm) sold well. 23 volumes have been published, all in the same small format for children's hands to hold. Beatrix Potter wrote until around 1920 when her eyes began to weaken. Potter's last book, The Tale of Little Pig Robinson , was published in 1930.

Norman Warne

The publisher Frederick Warne & Company was a family that was conducted after the death of founder Frederick of his three sons. In reviewing her books, she usually worked with Norman Warne, the youngest of the three brothers, who was still unmarried. Both became increasingly familiar with each other, which is particularly evident in the business letters, in which the tone became less and less formal and personal. The gradually developing acquaintance suffered from the frequent absences of Beatrix Potter, who accompanied her parents on various trips, and the regular business trips that Norman Warne had to undertake for the publisher. In 1904 the two wrote each other almost every day, which was met with increasing opposition from Beatrix Potter's mother. A family that earned its income through direct business activity (in English "being in the trade" ) did not correspond in the social hierarchy to the position that the Potter family occupied. Helen Potter prevented, among other things, Beatrix from accepting an invitation to lunch at which she would have entered the house in which Norman lived with his mother and sister.

In 1905, shortly before the now 39-year-old Beatrix Potter was to accompany her parents again for a longer summer stay, Norman Warne wrote to ask for her hand. When she informed her parents that she wanted to accept the application, this was met with fierce opposition. There was a major rift between her and her parents. They allowed her to be engaged unless it was made public. However, Norman Warne died of pernicious anemia soon after the engagement .

Lake District

Purchase of the Hill Top Farm

After Norman Warne's death, thanks to her income and a small inheritance from an aunt, Potter was able to buy Hill Top Farm in the Lake District near the village of Sawrey. The detachment from her parents and her efforts to process her grief for her deceased fiancé and to reorganize her life triggered a new phase of creativity in Potter. When she bought the Hill Top Farm, Potter was the author of six popular children's books. Over the next eight years after purchasing the farm, for which she paid £ 2,805, she wrote 13 more stories, some of which her biographer Linda Lear says are among the best of her own.

The farm was run by farmer John Cannon and his family, and Potter initially left him in that position while she familiarized herself with the life of a farmer. She made modifications to the farmhouse and purchased additional land. After looking at a number of successful farmhouse extensions, she began expanding Hill-Top Farm to include both she and the Cannon family of four. The Cannon family moved into the new wing, while Potter wanted to live in the old part of the farmhouse. The old farmhouse offered a number of surprises, including a staircase hidden in thick masonry, but also a surprising number of rats that lived in the house and that at first, despite all efforts, could not be driven away. The problem with the rats inspired Potter's story, The Tale Of Samuel Whiskers .

Country Life

Potter still lived temporarily in London or accompanied her parents on their extended summer stays and had to organize their extensive household in addition to their farm when their parents were increasingly health-impaired. Potter returned to Hill Top Farm for an increasingly longer period of time. Gradually, the number of animals on the farm also increased, where pigs had previously been bred. Cannon acquired 16 traditional landrace Herdwick ewes in the fall of 1906 and Potter looked forward to lambs on their farm this coming spring. In the summer of 1907, six dairy cows were added and the first dog, the Collie Kep. The alterations to the farm were completed in October 1907. In addition to the extended living spaces, the farm now also had a new barn and a milking parlor. The residential buildings now had running water and sanitary facilities in the house. The new environment inspired Potter to create new stories. The result was The Tale of Jemima Puddle-Duck (eng. The story of Jemima Pratschel-Watschel ), the story of a naive duck - dressed in a bonnet and scarf - which is looking for a safe place to lay its eggs. The duck's name is certainly a throwback to Jemima Blackburn , a well-known Victorian illustrator of ornithological works. Potter had received one of her books for her tenth birthday and had met the illustrator personally in 1891. The collie Kep plays a role in the story and saves Jemima from the fox, but the pictures also show the new barn, the front door of the new farmhouse, the newly laid out rhubarb patch and the wrought iron gate that Potter had installed at the entrance to the kitchen garden. The story was an instant hit, and a “Jemima” doll also proved very successful.

Further land purchases and the marriage to William Heelis

By the dawn of 1909, Potter had published a total of 14 books that were considered children's classics and was making a handsome income from them. There was also income from the sale of merchandising items. Among other things, there was wallpaper and tea sets decorated with characters from Potter's stories, as well as porcelain figures, a Peter Rabbit coloring book and a Jemima puddle doll. Potter used this income not only to expand her animal population, but also to purchase additional land. She preferred to buy land that was adjacent to her land, but also farms that came on the market at a particularly low price.

When she first bought land in 1905, Potter had been represented by her father's lawyers. As she later found out, they hadn't really acted in their interests and paid an inflated price for the farm. She found another law firm, a local firm with offices in the nearby towns of Hawkshead and Ambleside . The Hawkshead office was led by two partners, William Dickenden Heelis and his 38-year-old cousin, William Heelis. The latter was increasingly the one who advised her on purchases and also made her aware of farms that were coming to market cheaply. In May 1909, she acquired, among other things, the already leased Castle Farm, which was directly adjacent to her land. She gradually became one of the larger landowners in the area, having owned Buckle-Yeat-Croft in addition to the Hill-Top farm. In 1913 Potter was also able to acquire parts of the Sawrey House Estate. As early as 1912, Potter was elected to represent the landowners in the Landowner's Community Association. The Landowner's Community Association was responsible, among other things, for maintaining the roads and resolving disputes over ownership limits.

In 1912, William Heelis asked Beatrix to marry him, and she agreed. Again Beatrix's parents disliked the connection and they raised the same objection as before against Norman Warne: he was not equal to theirs. For a long time Potter was also concerned with the question of the extent to which, as a daughter, she was obliged to support her now frail parents at their age. Her cousin Caroline Hutton Clark, herself happily married, and her brother's surprising admission that he had been secretly married to a farmer's daughter for eleven years finally gave Potter the impetus to marry. William Heelis and Beatrix Potter were married on October 14, 1913 in St. Mary's Abbey, Kensington ; Beatrix was 47. The choice of church corresponded to the wish of Potter's parents: St. Mary Abbots was one of the churches in which socially ambitious married couples got married. Potter's wedding costume, however, was a testament to the country life Potter had chosen: it was tweed woven from the wool of Herdwick sheep. They lived at Castle Cottage in Sawrey from then on because the old Hill Top Farmhouse was too small for a couple and meant living too close to the Cannon family. William Heelis continued to work as a lawyer, Potter continued her hill-top farm from Castle Cottage. Agriculture was her main interest now, but she continued to write children's books, although the number of books she published annually declined.

Potter's father died on May 8, 1914. He left her and her brother £ 35,000 each, a substantial fortune. Helen Potter initially rented a small country house not far from Sawrey Estate and a year later bought a small country house near Potter's new home.

Increasing political commitment

Potter, who was not a supporter of women's suffrage, was still politically active from 1909 onwards. Free trade agreements and unfair copyright laws were the first areas Potter got involved. Because their publisher had not protected their rights in the USA, pirated copies of Peter Rabbit appeared there and also came onto the German market. Merchandising products like the Jemima doll, which she actually wanted to have produced in the UK, were too expensive if they were made locally compared to toys from Germany. Their commitment to stronger protective tariffs and better copyright rights was ultimately unsuccessful. When the British government initiated a census of horses, Potter took action again. A horse count was a necessary first step if horses were to be drafted for military use. On the grounds that she was also the owner of a horse, she put up a leaflet highlighting the scarcity of horses in rural areas and arguing that a farmer whose horses were drawn in received compensation for the animals, but not for the harvest that can no longer be collected. On the grounds that the leaflet would be implausible for a woman to sign, she signed Yours truly, North Country Farmer , had a thousand leaflets printed and sent to rural newspapers, farm show organizers, and agricultural machinery sellers.

In the winter of 1911, she began a campaign to protect the Lake District, to which she worked for the rest of her life. That year , seaplanes began to take off and land on Windermere , the largest natural lake in the Lake District. At the same time it was planned to build an aircraft factory on the banks of Cockshott Point. From Potter's point of view, these aircraft affected life in the Lake District several times. The seaplanes were a threat to boat traffic and fishing, and with their infernal noise, they restricted what made life in the Lake District: seclusion and tranquility. She started a letter campaign again. In January 1912 one of her letters appeared in Country Life magazine in which she protested violently against the establishment of the factory and an apparently planned commercial route to Windermere. A little later one of her letters also appeared in the London Times . She was not alone in her protest - Vicar Hardwicke Drummond Rawnsley, whom she knew from her first summer stay in the Lake District in 1882, also organized a protest against these plans. It was the first campaign that Potter was involved in and that achieved its goal. In August 1912, both the Home Office and the British Chamber of Commerce conducted an investigation into the matter. Neither the planned route nor the aircraft factory came to fruition.

In addition to her role as the landowner's representative in the Landowner's Community Association, Potter also became a member of the Footpath Association, a further step in Potter's increasingly active role in local politics in the Lake District. Potter was aware that tourists repeatedly caused damage to the long stone walls that were typical of the region and left gates open so that cattle would escape from their pastures. Nevertheless, she advocated sufficient hiking trails through the heathen of this region, because she was convinced that tourism was necessary if one wanted to preserve the characteristics of the Lake District.

Potter was also becoming increasingly aware of the poor health care in this rural area. She had seen the challenges the Spanish flu , which broke out at the end of the First World War, posed to such a relatively isolated region. She was also aware of the frequency with which women died unnecessarily in childbirth or the elderly on farms in the remote hills suffering from illness and death without assistance. Very few of the tenants, shepherds and farm laborers could afford to call a doctor. It was therefore her goal to organize a community nurse for the region. Potter was on the committee that organized the necessary resources. She gave the nurse rent-free a small house that she owned on the outskirts of Hawkshead.

First World War

The Cannon family had previously been administrators of the Hill-Top farm and provided the majority of the labor needed on the farm. However, the beginning of the First World War meant that these were no longer sufficient to manage the farm. John Cannon's health was restricted, one of his sons had already been drafted into the military, and it was foreseeable that the second son of the Cannon family would follow him very soon. Beatrix Potter had taken on an increasing part of the workload over the years, but this was no longer enough.

In a letter from Potter published in the Times, she complained that young, able women made significantly more money in the munitions factories than when they worked in agriculture. Potter agreed to hire a capable woman to work on their farm. Potter's letter in the Times caught the eye of Eleanor Choyce, a former governess with farming experience. There was an exchange of letters with Potter in which she assured, among other things, that she was able to pay a decent salary, that her farm consisted of 9 acres of arable land and 111 acres of pastureland, and that her livestock consisted of 2 horses, 9 to 10 cows , Calves and 60 sheep. Eleanor Choice began working on Hill-Top Farm for several months in the spring of 1916 - and returned to help out in the years that followed. For Potter, however, it was more important that a friendship began between them that lasted until Potter's life.

After the First World War: Established sheep farmer

In the years after World War I, Potter became increasingly aware that many farmers in the area were getting into financial difficulties and not only were logging their land but also selling their Herdwick herds, at risk of creating this breed of Lake District sheep would go away. She was well acquainted with some of the people in the administration of the National Trust and was therefore well aware of both the qualities of this breed of sheep and its importance to the region. As early as 1919, Potter was regularly sending some of her Herdwicks to livestock exhibitions, but always remained without any award. According to their landlady, this was because the Hill-Top Farm was not in the right conditions for Herdwicks - the farm had too rich soil for the breed, which thrived better in poor pasture. In 1923, Potter purposefully bought the Troutbeck Park farm, high in the hills of the Lake District, with the express intention of rebuilding this run-down farm and establishing a Herdwick herd of 1,100 animals. At the time of the purchase, Potter decided that this farm should be transferred to the National Trust after her death. In 1927 1,000 sheep were grazing on the Troutbeck Park farm.

In 1924 Potter became one of the few female members of the Herdwick Sheep Breeders' Association. Potter, who preferred to wear tweed costumes made from the wool of her sheep and, despite her affluence, mostly walked around in wooden shoes, was initially reputed by her fellow breeders to be just an eccentric hobby breeder with a sentimental penchant for this breed. According to Potter biographer Linda Lear, however, her colleagues underestimated how closely Potter, who was known for her detailed animal stories, could observe and what excellent knowledge of anatomy she possessed. She was very capable of judging the build and wool of a sheep. In 1927, Potter bought the Herdwick ram Cowie at the cattle auction, which had won awards for four years in a row at the Eskdale cattle show . In the same year, lambs from their flocks won prizes at livestock exhibitions for the first time. Together with her estate manager Tom Storey, she started a targeted breeding and exhibition program. In 1929, her ewes won first prizes at all major livestock shows in Keswick , Cockermouth , Ennerdale , Loweswater and Eskdale. She repeated this success the next year and also won the award for the best ewe in the Lake District. Her expertise gradually found recognition: in 1935 she was elected chairman of the Keswick Agricultural Show, and from then on she was a regular judge at the exhibitions.

death

In March 1943, the members of the breeding association elected Potter as president. However, Potter died of complications from bronchitis before she could take up this position. She bequeathed to the National Trust the 16 square kilometers of land she had acquired over the years in the region and specifically stated that Herdwicks were to be kept on it. The rights to her books were given to the nephew of her former fiancé, Frederick Warne Stephens. Hilltop Farm has been restored and opened to the public.

William Heelis died in August 1945.

Influences

Childhood rich in books and stories

Beatrix Potter grew up very isolated from other children by today's standards. However, due to the family's affluence, her childhood was also a very privileged one, which gave her literary and artistic opportunities to develop. Her Calvinist nanny, Ann Mackenzie, introduced Beatrix Potter to Scottish fairy tales and fables right from the start. As Potter himself later admitted, her nanny had bequeathed her "a firm belief in witches, fairies and the creed of the terrible John Calvin (his creed has worn out, but the fairies stayed)". Mackenzie read Potter not only stories from the Old Testament but also John Bunyan's pilgrimage to blessed eternity , Harriet Beecher Stowe's uncle Tom's hut , the fables of Aesop , the fairy tales of the Brothers Grimm and Hans Christian Andersen, and Walter Scott's Waverley . Charles Kingsley's fantastic story of the water children was also one of her children's books .

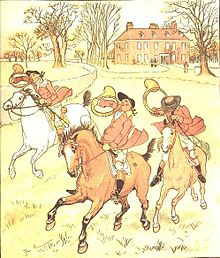

The Potters also acquired the children's books, which were becoming fashionable at the time. Beatrix Potter was familiar with the work of Walter Crane , Kate Greenaway and Randolph Caldecott from an early age. All three illustrators preferred to draw their characters in clothing from the early 19th century. Beatrix Potter also took up this convention in her later work. Her father held Caldecott in high esteem and bought three drawings from the 1880 cycle The Three Jovial Huntsmen from him. The date of purchase is not known, but Beatrix repeatedly drew copies of these works and unconsciously also adopted parts of his working method: the light color palette, the sparingly used lines and the use of paper that remained white.

Other authors with influence on Beatrix Potter's work

In 1880 the Uncle Remus Stories by the American author Joel Chandler Harris appeared for the first time . The stories were widely read in the Potter family, and between 1893 and 1896 Beatrix Potter drew eight illustrations of Tales of Harris.

Harris' tales, in which talking animals played a large role, had a great influence on contemporary writers in both Great Britain and North America. The humor was subversive, the dialogues virtuoso, the stories exciting and the protagonist of the stories, “Brer Rabbit”, was extremely cunning, cunning and charming at the same time. The charm of the stories, however, was also due to the fact that these seemingly naive fables were set in everyday situations. Like Potter, writers such as Rudyard Kipling ( The Jungle Book ) , Kenneth Grahame ( The Wind in the Willows ), and AA Milne ( Winnie the Pooh ) were significantly influenced by these stories.

At the end of the 19th century, a number of British publishers began publishing picture books for children and had commercial success. The Golliwog books, which were first published in 1895 , had great success . The Story of Little Black Sambo , a small-format picture book by Helen Bannermann , a Scottish woman living in India and published in 1899, was still successful . Little Black Sambo - which had to be reprinted four times in four months due to the sales success - also inspired Beatrix Potter to the format her picture books should have. The success that these books had ultimately convinced other publishers to enter this market segment.

Movie

In 2006, Australian director Chris Noonan filmed the writer's life under the title Miss Potter . Beatrix Potter is played by Renée Zellweger , who was nominated for a Golden Globe Award for her role , and Lucy Boynton , who played her as a child. Ewan McGregor plays her fiancé, Norman Warne .

Honor

2016 was the 150th anniversary of Beatrix Potter's birthday. The Royal Mint , the mint of the United Kingdom , took this as an opportunity to mint 50 pence coins with an image of Peter Rabbit. It is the first British coin to feature a fictional character from a children's book.

A crater of Venus was named after her in 1994 .

Publications (selection)

Works (German titles)

- The story of Peter Hase

- The story of Mr. Schnappeschlau

- The story of Ribby and Duchess

- The story of the two cheeky mice

- The story of Mrs. Tiggy-Wiggel

- The story of the poor tailor

- The story of Piggy Softie

- The story of Mieze Mozzi

- The story of Jeremias Wheal

- The story of Timmy Triptrap

- The story of the Flopsi bunnies

- The story of the bad, wild rabbit

- The story of Jemima Pratschel-Watschel

- The story of curries and kappes

- The story of the little pig Robinson

- The story of Thomasina Tittelmaus

- The story of Schwapp the pig

- The story of Stoffel kitten

- The story of squirrel nusper

- The story of Feuchtel Fischer

- The story of Bernhard Schnauzbart

- The story of Benjamin Rabbit

- The story of Hans Hausmaus

- The story of Fritz Zehenspitz

- The story of Mrs. Tupfelmaus

- The story of the Plumps rabbit family

- The story of Mrs. Igelischen

- The story of Emma Ententropf

Works (English titles)

- The Tale of Peter Rabbit (1900, Frederick Warne & Co.)

- The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin (1903, Frederick Warne & Co.)

- The Tailor of Gloucester (1903, Frederick Warne & Co.)

- The Tale of Benjamin Bunny (1904, Frederick Warne & Co.)

- The Tale of Two Bad Mice (1904, Frederick Warne & Co.)

- The Tale of Mrs. Tiggy-Winkle (1905)

- The Pie and The Patty-Pan (1905)

- The Tale of Mr. Jeremy Fisher (1906)

- The Story of a Fierce Bad Rabbit (1906)

- The Story of Miss Moppet (1906)

- The Tale of Tom Kitten (1907)

- The Tale of Jemima Puddle-Duck (1908)

- The Tale of Samuel Whiskers or, The Roly-Poly Pudding (1908)

- The Tale of The Flopsy Bunnies (1909)

- The Tale of Ginger and Pickles (1909)

- The Tale of Mrs. Tittlemouse (1910)

- Peter Rabbit's Painting Book (1911)

- The Tale of Tommy Tiptoes (1911)

- The Tale of Mr. Tod (1912)

- The Tale of Pigling Bland (1913)

- Tom Kitten's Painting Book (1917)

- Appley Dapply's Nursery Rhymes (1917)

- The Tale of Johnny Town-Mouse (1918)

- Cecily Parsley's Nursery Rhymes (1922)

- Jemima Puddle-Duck's Painting Book (1925)

- Peter Rabbit's Almanac for 1929 (1928)

- The Fairy Caravan (1929)

- The Tale of Little Pig Robinson (1930)

- Sister Anne (1932)

- Wag-by-Wall (1944)

- The Tale of The Faithful Dove (1955)

- The Sly Old Cat (1971)

- The Tale of Tuppenny (1973)

literature

- Alexander Grenstein: The remarkable Beatrix Potter. International Universities Press, Madison CT 1995, ISBN 0-8236-5789-2 .

- Anne Stevenson Hobbs: Beatrix Potter's art. Paintings and drawings. Frederick Warne, London 1989, ISBN 0-7232-3598-8 .

- Judy Taylor et al. a .: Beatrix Potter. 1866-1943. The artist and her world. Frederick Warne et al. a., London a. a. 1987, ISBN 0-7232-3521-X .

- Margaret Lane: The Magic Years of Beatrix Potter. Frederick Warne, London a. a. 1978, ISBN 0-7232-2108-1 .

- Linda Lear: Beatrix Potter - The extraordinary life of a Victorian genius. Penguin Books, London 2007, ISBN 978-0-141-00310-8 .

- Leslie Linder: A history of the writings of Beatrix Potter. Including unpublished work. Frederick Warne, London 1971.

- Margaret Lane: The tale of Beatrix Potter. Frederick Warne, London 1946.

- Sarah Gristwood: The story of Beatrix Potter , London: National Trust, 2016, ISBN 978-1-909881-80-8

- Matthew Dennison: "Over the hills and far away": the life of Beatrix Potter , London: Head of Zeus, 2017, ISBN 978-1-78497-564-7

Web links

- Literature by and about Beatrix Potter in the catalog of the German National Library

- Beatrix Potter's curriculum vitae on the website of your publisher

- Works by Beatrix Potter in Project Gutenberg ( currently not usually available for users from Germany )

- Hill top. Visit Cumbria, accessed July 28, 2016 .

- Petri Liukkonen, Ari Pesonen: (Helen) Beatrix Potter (1866–1943). Kuusankoski City Library, 2008, archived from the original on September 23, 2014 ; accessed on July 28, 2016 .

- Beatrix Potter Society website

- Miss Potter in the Internet Movie Database (English)

Individual evidence

-

↑ Linda Lear: Beatrix Potter Biography . bpotter.com 2007, accessed July 28, 2016.

Linda Lear: About Beatrix Potter . The Beatrix Potter Society, 2011, accessed July 28, 2016. - ↑ Lear: Beatrix Potter . 2007, p. 9.

- ↑ Lear: Beatrix Potter . 2007, p. 12.

- ↑ Lear: Beatrix Potter . 2007, p. 13.

- ↑ Lear: Beatrix Potter . 2007, p. 18.

- ↑ Lear: Beatrix Potter . 2007, p. 19.

- ↑ Lear: Beatrix Potter . 2007, p. 20.

- ↑ Lear: Beatrix Potter . 2007, pp. 19, 20.

- ↑ Lear: Beatrix Potter . 2007, p. 22.

- ↑ Lear: Beatrix Potter . 2007, p. 23.

- ↑ a b c Lear: Beatrix Potter . 2007, p. 24.

- ↑ Lear: Beatrix Potter . 2007, p. 37.

- ↑ Lear: Beatrix Potter . 2007, p. 31.

- ↑ Lear: Beatrix Potter . 2007, p. 3.

- ↑ Lear: Beatrix Potter . 2007, p. 45. The original quote is: "Plenty of people can draw, but you and my son John have observeration."

- ↑ Lear: Beatrix Potter . 2007, p. 33.

- ↑ a b c d Lear: Beatrix Potter . 2007, p. 47.

- ↑ Lear: Beatrix Potter . 2007, p. 55. The original quote is: "I can't zettle to any thing but my painting, I lost my Patience over everything else."

- ↑ Lear: Beatrix Potter . 2007, p. 52.

- ↑ a b c Lear: Beatrix Potter . 2007, p. 53.

- ↑ Kathryn Hughes: The Victorian Governess . The Hambledon Press, London 1993, ISBN 1-85285-002-7 , p. 62.

- ↑ Lear: Beatrix Potter . 2007, p. 67.

- ↑ Lear: Beatrix Potter . 2007, p. 67. The original quote reads: “I have liked my last governess best on the whole - Miss Carter had her faults, and was one of the youngest people I have ever seen, but she was very good-tempered and intelligent. [...] The rules of geography and grammar are tiresome, there is no general word to express the feelings I have always entertained towards arithmetic. "

- ↑ Lear: Beatrix Potter . 2007, p. 70 and p. 72.

- ↑ Lear: Beatrix Potter . 2007, p. 69.

- ↑ Lear: Beatrix Potter . 2007, p. 70.

- ↑ Lear: Beatrix Potter . 2007, p. 89.

- ↑ Lear: Beatrix Potter . 2007, p. 94.

- ↑ Lear: Beatrix Potter . 2007, p. 138.

- ↑ Lear: Beatrix Potter . 2007, p. 73.

- ↑ Lear: Beatrix Potter . 2007, pp. 76, 77.

- ↑ Lear: Beatrix Potter . 2007, p. 85.

- ↑ Lear: Beatrix Potter . 2007, p. 98.

- ↑ a b Lear: Beatrix Potter . 2007, p. 127.

- ↑ Lear: Beatrix Potter . 2007, p. 86. In the original the quote is: "I don't know what to write to you, so I shall tell you a story about four little rabbits whose names were - Flopsy, Mopsy, Cottontail, and Peter".

- ↑ a b Lear: Beatrix Potter . 2007, p. 143.

- ↑ Lear: Beatrix Potter . 2007, p. 148.

- ↑ a b Lear: Beatrix Potter . 2007, p. 149.

- ↑ a b Lear: Beatrix Potter . 2007, p. 176.

- ↑ Lear: Beatrix Potter . 2007, p. 198.

- ↑ Lear: Beatrix Potter . 2007, p. 199.

- ↑ Lear: Beatrix Potter , p. 206.

- ^ Lear: Beatrix Potter , p. 207.

- ^ Lear: Beatrix Potter , p. 209.

- ^ Lear: Beatrix Potter , p. 211.

- ↑ a b Lear: Beatrix Potter , p. 217.

- ^ Lear: Beatrix Potter , p. 236.

- ^ Lear: Beatrix Potter , p. 220.

- ^ Lear: Beatrix Potter , p. 222.

- ↑ a b c d Lear: Beatrix Potter , p. 227.

- ^ Lear: Beatrix Potter , p. 228.

- ^ Lear: Beatrix Potter , p. 265.

- ↑ Lear: Beatrix Potter , p. 277.

- ^ Lear: Beatrix Potter , p. 252.

- ^ Lear: Beatrix Potter , p. 255.

- ↑ Lear: Beatrix Potter , p. 260.

- ↑ Lear: Beatrix Potter , p. 261.

- ^ Lear: Beatrix Potter , p. 266.

- ^ Lear: Beatrix Potter , p. 269.

- ^ Lear: Beatrix Potter , p. 233.

- ↑ a b Lear: Beatrix Potter , p. 232.

- ^ Lear: Beatrix Potter , p. 241.

- ^ Lear: Beatrix Potter , p. 243.

- ^ Lear: Beatrix Potter , p. 278.

- ^ Lear: Beatrix Potter , p. 303.

- ^ Lear: Beatrix Potter , p. 305.

- ↑ Lear: Beatrix Potter , p. 273.

- ^ Lear: Beatrix Potter , p. 275.

- ↑ Linda Lear: Beatrix Potter , 2007, p. 328.

- ↑ Linda Lear: Beatrix Potter , 2007, p. 317

- ↑ Linda Lear: Beatrix Potter , 2007, p. 327

- ↑ Linda Lear: Beatrix Potter , 2007, p. 334

- ↑ Linda Lear: Beatrix Potter , 2007, p. 436

- ↑ Lear: Beatrix Potter . 2007, p. 405ff.

- ↑ Lear: Beatrix Potter . 2007, p. 30. The original quote is: "... a firm belief in witches, faires and the creed of the terrible John Calvin (the creed rubbed off, but the fairies remained)".

- ↑ Lear: Beatrix Potter . 2007, p. 30.

- ↑ Lear: Beatrix Potter . 2007, p. 33.

- ↑ Lear: Beatrix Potter . 2007, p. 131.

- ↑ Lear: Beatrix Potter . 2007, pp. 144, 145.

- ↑ a b Maev Kennedy: Rare Edition of Beatrix Potter's Peter Rabbit set to sell for 18,000 British pounds . The Guardian , March 4, 2016, accessed July 28, 2016.

- ^ Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature , accessed July 26, 2017

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Potter, Beatrix |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Potter, Helen Beatrix (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | British children's author and illustrator |

| DATE OF BIRTH | July 28, 1866 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | London |

| DATE OF DEATH | December 22, 1943 |

| Place of death | Sawrey , Lancashire , England |