Calcidius

Calcidius (also written Chalcidius ) was a late antique scholar and philosopher . He lived in the 4th and maybe the early 5th centuries in the west of the Roman Empire .

As a Platonist , Calcidius wanted to make Plato's natural philosophy , which is presented in the Timaeus dialogue in Greek, accessible and understandable to an educated reading public who no longer had sufficient knowledge of Greek. To this end, he translated part of the Timaeus into Latin and wrote a detailed Latin commentary on the demanding text, which required explanation. He also took Christian ideas into account. To what extent he confessed to Christianity is unclear and controversial in research.

Calcidius emphasized his critical distance from the earlier Plato interpreters. He was particularly interested in the mathematical basis of the world order, the relationship between the different components of the universe and the problem of human free will in a world controlled by Providence . A core idea of his cosmology and anthropology is the concept of the analogy between the cosmos and man. The human being appears as an image of the cosmos, as a small world.

In the Middle Ages, the work of Calcidius was studied intensively. For centuries it formed the main basis of the direct reception of Plato in the Latin West and gave impetus to the fusion of Platonic and Christian cosmology. Its strong aftermath extended to early Renaissance humanism . Modern research is particularly concerned with the history of its effects and the question of the sources that are now lost and available to Calcidius.

Life

The origin of the writer is unknown. Apparently he called himself Calcidius; the alternative form of the name Chalcidius is not considered authentic. The name is of Greek origin (Χαλκίδιος Chalkídios ), but the latinization of the Ch was changed to C, and aspiration was ignored.

Almost nothing is known about the life of Calcidius. In the older research the assumption dominated that he lived in the first half of the 4th century. The dedication letter to his work, which he addressed to his close friend Osius, seemed to offer a clue for this. The letter shows that Osius was a respected scholar who commissioned Calcidius to do the translation. In part of the handwritten tradition, Osius is referred to as the Spanish bishop and Calcidius as the archdeacon . In fact, there was a bishop of Cordoba named Ossius (Hosius) who died in the 350s. The chronological classification of the activity of Calcidius, which was previously common, is based on this. Jan Hendrik Waszink has shown, however, that the identification of Calcidius' friend with the bishop of the same name is insufficiently documented, as their handwritten evidence only dates back to the 11th century and none of these manuscripts has any relation to Spain. There is no convincing evidence that Calcidius on the Iberian Peninsula lived. Thus the older dating of the life and work of the Timaeus commentator lacks a solid basis.

Based on this result, Waszink has pleaded for a late dating. Mainly for linguistic reasons, he put forward the hypothesis that Calcidius only translated and commented on the Timaeus at the turn of the 4th and 5th centuries, when it was no longer a matter of course for educated people in the west of the Empire to have a profound knowledge of Greek. This probably happened in Italy. The client can probably be identified with a noble Roman named Hosius from Milan, attested only by his grave inscription there, who successively held the high court offices of comes rerum privatarum and comes sacrarum largitionum . Calcidius was said to have worked in his friend's hometown. Pierre Courcelle Christine Ratkowitsch and Béatrice Bakhouche have also spoken out in favor of the work being created in Milan; Eckart Mensching has agreed to date it around 400 . However, John M. Dillon has objected to Waszink's argument . In recent research, the question is mostly considered to be open; it cannot be ruled out that the old equation of the client with the bishop of Cordoba is true.

The religious attitude of Calcidius is not clear from his remarks. He was obviously not an ardent Christian, because he showed no preference for the Christian doctrine of creation over the Platonic and did not try to Christianize the Timaeus . Passages in which he referred to the Bible and the exegesis of the "Hebrews" seem to indicate an at least nominal commitment to the Christian faith . However, this is not proof of belonging to Christianity; it only shows that he was addressing Christian readers, among whom apparently his friend and client Osius was one. Some historians consider Calcidius to be pagan , others to be a Christian. Researchers who believe that he moved in an intermediate zone between biblical faith and the worldview of Timaeus , either as a nominal Christian who clung to Platonic cosmology, or as a pagan but Christian-influenced philosopher, follow a middle line .

Translation and commentary on the Timaeus

The Timaeus translation by Calcidius with commentary is, as far as is known, his only work. Cicero had already translated about a quarter of the dialogue into Latin. Also Calcidius translated only part of the Timaios which constitutes slightly less than the first half (from 17a1 to 53c2 after the Stephanus pagination ). His translation differs considerably from Cicero's, which he may not have known. The commentary - the only surviving Latin commentary on Plato from antiquity - only refers to the text from 31c4 to 53c3.

After introductory remarks, 27 topics are listed in the commentary which correspond to the entire content of Plato's Dialogue and whose discussion is announced. However, only the comments from the commentator on topics 1–13, which are dealt with in the translated part of the dialogue, have been preserved. It is not known whether this is due to the incompleteness of the surviving text or to a termination of the project. The presentation progresses from simpler to more complex topics. In the dedication letter, Calcidius informed his client Osius that he had initially only written part of the planned work and that he was now sending it as a sample; if the recipient were to enjoy it, it would encourage him, Calcidius, to continue the work.

Calcidius stated that there could be different reasons why a statement seemed obscure and therefore in need of explanation. One possibility is that the author himself presents his material in a way that is difficult to understand, either to consciously conceal the content - Calcidius named Heraclitus and Aristotle as examples - or out of inability. The other possible reasons are the unfamiliarity of something new, incompetence of the audience and a difficulty in understanding, which is in the nature of the topic. With the Timaeus , the demanding topic is the cause of the difficulties of understanding. Plato requires his readers to have considerable previous knowledge of arithmetic , geometry , astronomy and music (the "mathematical" subjects according to ancient terminology). For Calcidius, this made it necessary to comment. He saw the meaning of his activity not only in the descriptive explanation of Plato's statements, but also in the proof of their correctness through clearly evident conclusions (rationes evidentes) .

When writing his commentary, Calcidius consulted the relevant older literature as far as it was still available and accessible to him in his time. At first, Plato's own works, which he knew very well, provided him with information. He also made use of ideas from the treatise On the Good by the Middle Platonist Numenios and from the Timaeus commentary by the Peripatetic Adrastos of Aphrodisias . These two writings are lost today, except for fragments. It is disputed whether he had the work of Adrastos, to which he never explicitly referred anywhere, in the original text; also that of Numenios, whom he mentioned by name, he possibly only knew from quotations. At one point he reproduced a thesis by the Jewish theologian Philo of Alexandria , which comes from his work De opificio mundi ; but she was only known to him secondhand. Some researchers believe that he used the Timaeus commentary by Porphyry , which today only exists in fragments , while others reject this hypothesis or are skeptical. He referred several times to statements by Aristotle , but it is unclear whether his works were accessible to him in the full original text or whether only content reproductions and quotations from individual passages were available. The assumption expressed in older publications that Calcidius used Macrobius' commentary on Cicero's Somnium Scipionis does not apply, as this work was probably written much later than his Timaeus commentary.

Calcidius did not use the writings of the church fathers . He cited only one Christian author, the theologian Origen , whom he regarded as an authority and to whom he explicitly referred at one point. Significantly, Origen is a Christian thinker who was so strongly influenced by Platonism that, from the end of the 4th century, many Christians regarded it as at least suspicious. Several times Calcidius gave philosophical opinions, which he attributed to "Hebrews". One research suggests that the source for this "Hebrew" material was Origen's now-lost commentary on the Book of Genesis ; According to another hypothesis, Calcidius drew his knowledge from another work by Origen, the Stromateis , which is now also lost .

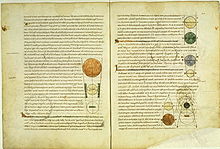

When discussing the subject matter of the mathematical subjects, Calcidius used 25 diagrams , some of which he took from older literature and some of which he designed himself. Six of the diagrams are geometric and arithmetic, they have the shape of geometric figures and illustrate the structure of the cosmos. Three concern music and, at the same time, the doctrine of the soul closely connected with it; they illustrate the harmony and at the same time the harmony of the world soul . They are number diagrams in the form of the Greek letter lambda (Λ). This method of representation, which is attested for the first time in Latin literature, is said to go back to the philosopher Krantor von Soloi († 276/275 BC). The other diagrams serve to illustrate astronomical statements.

Teaching

Classification in the history of philosophy

By the time Calcidius lived, Middle Platonism had already been replaced by Neoplatonism . In late antique philosophy, Neoplatonism was the undisputed dominant school direction. Nevertheless, the opinion is expressed in research that Calcidius should be classified under the Middle Platonists rather than the Neoplatonists from a content perspective. This is justified by the fact that his thinking does not leave the framework of Middle Platonic ideas and that many specifically Neoplatonic thoughts are not to be found in him. There is no connection to the Neoplatonic movement. Historians of philosophy, who consider him a Neoplatonist, disagree. They claim that he was influenced by the teachings of Porphyry , an early Neoplatonist.

The extraordinary respect that the pagan Middle and Neoplatonists showed for the authority of Plato was also very pronounced in Calcidius. On the other hand, he was critical of the interpretations that had been given to the teachings of the school founder over time. He vigorously opposed hypotheses that contradicted Platonic doctrine. When discussing optics , he found that Plato's theory had only been partially understood by scientists of later times. On the basis of a limited and therefore inadequate understanding, they would only have considered individual parts of Plato's explanation of vision and thus missed the whole. For Calcidius there was no doubt that the world view of Timaeus corresponds to the truth. He knew and used the fruits of the centuries-old tradition of the interpretation of Plato, but did not want to join this chain of tradition. Rather, he emphasized his direct recourse to Plato's text and confidently opposed his interpretation to all others.

Calcidius knew very well about the teaching traditions of the philosophy schools. In his commentary he commented on the teachings of the Stoics , which he rejected from a platonic point of view. He emphasized the contrast between Stoic and Platonic philosophy in assessing free will , fate and the role of matter in the world order. But his concept of providence shows stoic influence.

cosmology

The representation of the substance

Calcidius tried to make the rational world as a whole understandable to his readers, as it emerges from his interpretation from Plato's story. He set himself the task of revealing the invisible mathematical order of the timelessly valid, which is only accessible to thought. He used visual objects - diagrams - for this. The epistemological basis for this approach was his understanding of the sense of sight, which he praised as the most outstanding of all the senses. His thought was that everything created can only become an object of thought through the sense of sight, and thus a knowledge of the perfection of the world is made possible. Seeing is a means of knowledge, the real use of which only becomes apparent when what is seen is transferred to the realm of reason. The abstract-geometric diagrams should serve to convert visual perception into knowledge. Calcidius wanted to use them to illustrate the mathematical order of the cosmos. He wanted to show that the world order is characterized by precisely definable relationships between individual quantities. The diagrams were intended to reveal the perfection of the inerrancy established world.

In addition, the diagrams sometimes had the task of visually bringing about an insight that exposes the naive vision. The pictorial representations of the curvature of the sea level and the movements of the planets served this purpose. It was about the understanding of circumstances that appear to the ignorant beholder to be different from what they are. The diagrams should show how the interaction of the eye and intellect corrects a visual finding.

The principle of analogy

In calcidius' cosmology, the principle of analogy plays a central role. Plato had stated in Timaeus that the existence of the sensually perceptible world was due to the fact that divine influence had imposed a mathematical order on the unqualified primordial matter . This can be seen in the relationship of the four elements : fire is related to air like air to water and air to water like this to earth. Accordingly, the ratio of the elements is designed according to a geometric proportion , in which the first of four numbers is related to the second as the second to the third and the third to the fourth (for example 16: 8 = 8: 4 = 4: 2). Calcidius started from this mathematical analogy (proportional equality). He reproduced the Greek term analogía in Latin with ratio . He used diagrams to make things clearer. He emphasized the analogy between the world soul and the human soul , between the “world body” (mundanum corpus) and the human body as well as between the universe, the great cosmos, and the human being, which he describes as a cosmos in a small way (microcosm, Latin mundus brevis ) perceived. In order to enable the readers of Timaeus to understand the Platonic cosmology correctly according to his interpretation of the dialogue, he imparted to them the necessary knowledge about arithmetic and geometric proportions.

Fire and earth represent extreme opposites in the model; Air and water mediate between them according to the proportion and thus enable a construction of the cosmic body that keeps it in equilibrium and prevents its dissolution. The mathematical principle of analogy is applied to individual properties of the elements as well as to the property bundles that characterize the elements.

The heavenly realm

Plato did not deal with astronomical empiricism in his Timaeus . For Calcidius, on the other hand, it was important to show in the astronomical section of his commentary on the dialogue that Platonic cosmology was compatible with the astronomical knowledge of his time. He also wanted to bring Christian revelation into harmony with astronomy; he identified the star of Bethlehem with the Sirius ("dog star"). Apparently this is the only ancient attempt to equate it with a known star. One of the main concerns of the commentator was to explain the fact that some planetary movements appear to be irregular from the point of view of earthly observers, although the opposite is the case according to Platonic cosmology. With the means that were available to geocentric astronomy at the time, he tried to show that it was a matter of ordered movements and that the opposite impression was deceptive.

Calcidius located the abodes of beings in unearthly areas of the cosmos, for whom he used the terms “ angels ” and “ demons ” (daemones) . In his doctrine of these beings, he took up both Middle Platonic and biblical ideas. When translating a passage in the Timaeus that speaks of daímones , he gave explanatory notes : invisible divine powers called demons . He assumed that among these creatures there were not only good ones but also evil ones. He believed both to be instruments of divine providence. He saw in them mediators between the heavenly realm - the fire of the stars - and the earthly human world. Also between the demiurge , the mythical creator of the world, and humans, the daemones in Calcidius' view of the world occupy a mediating position. From his point of view, they are necessary components of the world order, because the world forms a continuum both physically and metaphysically , the cohesion of which must be guaranteed by mediating authorities. There are life forms in every area of the universe. The closer a demon is to the earth, the more it is adversely affected by it and the worse its character is. The middle position of the daemones between the divine and the human being is shown in the fact that on the one hand they are immortal like the gods and on the other hand capable of suffering like mortals. Here, too, Calcidius assumes a geometrical proportion: God is to angels or demons as he is to humans. The daemones are not purely spiritual beings, because they have ethereal or air-like bodies, but due to the nature of their body matter they are usually withdrawn from human sensory perception. However, some of them who live near the earth can make themselves visible. The human souls are immortal just like the supernatural beings, but they can be clearly distinguished from them, because the daemones are superior to the souls and represent a different kind of living beings. The idea spread by poets that there is a demonic presence in man, the inciting shameful behavior, Calcidius emphatically refused.

The matter

Calcidius dealt intensively with the nature of matter, which one was accustomed to call Hyle since Aristotle ; Plato had not used this expression before. Since the basic meaning of the Greek word hýlē is "forest", Calcidius - as far as known as the first Latin author - used the Latin word for "forest", silva , to denote the unformed, unpropertyless primordial matter dealt with in Timaeus . This allowed him a terminological distinction: the eternal, uncreated primordial matter (materia principalis) he called silva that the people familiar matter in the form of the four elements of fire, water, air and earth materia . He saw one of the basic principles (initia) of the world order in the non-sensually perceptible primordial matter . According to his understanding, the silva can be neither corporeal nor incorporeal, because such properties would already be determinations that do not apply to the absolutely indefinite, undifferentiated and therefore lacking in properties. Even the "tracks" (íchnē) of the elements that, according to the Timaeus already exist in primordial matter, are for Calcidius not physically; they are only potentially to be conceived of as physical because they form the basis of the physical materia . Primordial matter does not appear in the world of realized things, because matter that actually exists must always have properties.

Since the platonic primordial matter is determinate, it is also powerless; it plays a purely passive role in the Platonic world model. A difficult problem for the Timaeus interpreters is therefore the explanation of the chaotic movement that is ascribed to primordial matter in dialogue without its cause being given there. Calcidius took a position on this question, which is still controversial in research today, by denying that the primordial matter had a self-induced movement and assumed external influences as the cause.

Man in the cosmos

Calcidius dealt in detail with divine providence (providentia) and its relationship to fate (fatum) . This topic is not discussed in the Timaeus , but it was of central importance to the commentator; he had to deal with the stoic concept of providence and to work out the platonic position. According to the representation of Calcidius, the world is ruled by the “highest God”, whose powers, however, go beyond the human horizon. Providence is not directly exercised by this deity himself; rather , it is to be equated with the divine intellect, which the Greek thinkers called Nous . The divine will is to be located in the nous. People call this “providence”, but the essential thing is not that the future is foreseen, but that understanding, insight, is the characteristic of the divine spirit. Providence is the lawgiver of eternal and temporal life. It directly determines everything that belongs to the intelligible (purely spiritual and divine) world. On the other hand, it only has an indirect effect on the physical, sensually perceptible world. There the subordinate fatum rules , the divine law, which as the power of fate is responsible in this area for the implementation of the divine will. In addition, there is also human initiative and chance additions as additional factors. Thus human destinies depend only indirectly and in part on Providence.

Calcidius was primarily concerned with determining the relationship between the divine and human will in shaping individual fates. In doing so he turned against the thinkers, who denied divine providence, as well as against the fatalists , who did not grant the human will any autonomy, since all processes are irrevocably predetermined. According to his teaching, people make decisions that are not predetermined but are left to the discretion of the decisive person. However, the consequences that result from this are determined by the law of fate. Since fatum is exclusively good, it can in no way be the cause of evils. Calcidius defended this Platonic position against several objections by the Stoics, who ascribed a far more decisive role to predestination.

Calcidius understood the Timaeus as a continuation of Plato's dialogue Politeia . He saw the commonality of the two dialogues in the issue of justice . In the Politeia the justice that is valid in human affairs, the iustitia positiva , is sought and found. In Timaeus , Plato represented a more comprehensive justice, the iustitia naturalis . Calcidius considered this natural justice or adequacy (aequitas) , the order of the cosmos, to be the binding norm of positive law. He believed that it had a natural measure (genuina moderatio) by which it gave human laws and legal formulas their natural substance (substantia) when applied in legislation.

With the help of the Politeia , Calcidius presented his readers with a three-part hierarchical structure that he considered to be a fundamental organizing principle of the world. According to this model, the deity directs the universe from above, from the highest region of the sky. The execution of the divine will is incumbent on the daemones or angels who populate the middle area between the highest heavenly sphere and the earth. At the bottom are the earthly creatures; they are of the lowest rank and are under the control of their superior powers. In a properly built state - that is, based on the model of the cosmos - there is an analogous three-part order. Its population is divided into three classes : the small ruling elite of the philosopher rulers , the guardian class as executive authority, and the mass of the people, which are entirely dependent on caring control and guidance. This hierarchy should be reflected in the spatial shape of the city-state, the polis ; the residences of the rulers are said to be in the highest part of the urban area. The individual human being is structured in three parts according to the same principle: The rule is due to the “royal” soul as the bearer of reason (ratio) . It therefore has its seat at the top, in the head, which, as it were, represents the castle (arx) of the body. The will that expresses itself in courageous striving has to carry out the instructions of reason; he works with his strength and passion in the middle of the body, in the chest. The lower abdomen, in which the bodily desires stir, occupies the lowest place in rank and physically, it is only intended for obedience. Human emotions and desires, however, must not be equated with analogous animal ones; Since they are expressions of the soul of a rational being and are subject to reason, they stand above the analogous impulses of animals and acquire a rational character.

In this anthropological concept, the soul is an autonomous steering entity, the body a mere tool. Accordingly, Calcidius defended the Platonic theory of the soul in detail against the criticism of Aristotle and also turned against the assertion of other thinkers that the soul is corporeal. He said that the Aristotelian definition of the soul as the form of the body was wrong, the denial of an independent existence of the soul independent of the body was a grave error. He contrasted the Aristotelian understanding of the soul with the Platonic one, according to which the soul naturally belongs to a purely spiritual world and is active on its own without the need for a body.

reception

In late antiquity, the Latin Timaeus and the accompanying commentary received very little attention. The broad aftermath did not begin until the Middle Ages. The number of surviving manuscripts - there are at least 198 - shows the intensity of the preoccupation with the work.

Late antiquity

A late antique reception of Calcidius was suspected in the older research, but could not be proven. It was not until 1991 that Marion Lausberg showed that Macrobius took over a passage from the Latin Timaeus translation in the preface to his Saturnalia . It is uncertain whether the African Favonius Eulogius , a pupil of Augustine , used the commentary of Calcidius in his Disputatio de somnio Scipionis or whether the two authors copied a common Latin model; the former is considered more likely today.

Middle Ages and Early Renaissance

In the Middle Ages the Timaeus was known to the Latin-speaking scholarly world of the West primarily through the translation and commentary by Calcidius, but the older partial translation of Cicero was also accessible in some places. Often there was no difference in content between Plato's dialogue and commentary; Calcidius' interpretations were equated with Plato's view. As early as the 9th century the commentary was glossed over , that is, provided with explanations. The glossing was later expanded. In the course of time, a standard glossing was established that accompanied the text in the copies and was supplemented in the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance . Some editors and glossators inserted diagrams; they replaced the diagrams in the text of Calcidius with modified ones or provided the marginal glosses with their own diagrams.

Copies of the translation and the commentary were available in Gaul as early as the 6th century and in Hispania by the 7th century at the latest. The oldest surviving Calcidius manuscripts date from the 9th century. Already at the beginning of the 9th century dialogue and commentary received attention among Alkuin's students .

In the second half of the 10th century two of the most respected scholars, Abbo von Fleury and Gerbert von Aurillac , studied and referred to the work of Calcidius. Abbo recommended reading the Timaeus commentary, in which he saw a good representation of the four subjects of the quadrivium (arithmetic, geometry, music, astronomy), and used the astronomical part for his Easter calculation . At the time of Abbos and Gerbert - possibly in connection with their activities - the "Brussels glosses" for the commentary were created, a mathematical glossing with the glossator's own diagrams in a manuscript that is now in Brussels.

In the 11th century interest in the commentary grew and peaked; 18 manuscripts made at the time have been preserved. One read Plato's Dialogue from the perspective of the late antique commentator, whose work was used as a textbook for the four quadrivial subjects. A brief introduction (accessus) to Calcidius was added to some copies . The basis of the accessus was a note that referred to the writer as a deacon or archdeacon and identified the client with Bishop Ossius of Córdoba; further details were added in later manuscripts. From then on Calcidius was considered a cleric. This benefited his authority and protected him from the suspicion that he had represented heresy as a pagan.

In the 12th century, a detailed glossing of the Timaeus began, which also included the state-theoretical and anthropological statements of Calcidius. Particular attention was paid to the application of the cosmic principle of analogy to the state and man, which Calcidius had set out in his commentary following Plato's statements in Timaeus and in the Politeia . However, preoccupation with the commentary declined; he was pushed into the background by the emerging medieval Timaeus commentary. From the 12th century on, the Timaeus translation was mostly copied without the commentary of Calcidius.

An important source of inspiration for intellectual life in the 12th century was the " School of Chartres ". It was a group of influential scholars of early scholasticism who gave the Christian doctrine of creation a philosophical interpretation. They proceeded from the basic assumptions of Platonism and tried to show a correspondence between the worldview of Timaeus and that of the biblical account of creation. Among the well-known “Chartresians” were Bernhard von Chartres and Wilhelm von Conches , two scholars who worked in the first half of the 12th century and who dealt intensively with Platonic natural philosophy. Bernhard is considered to be the author of the Glose super Platonem , an anonymously transmitted Timaeus commentary in the form of glosses, or at least part of these glosses. Wilhelm emerged as the author of natural philosophical writings and interpreter of the Timaeus . Both commentators dealt with the work of their predecessor Calcidius. In the commentary on glosses ascribed to Bernhard, the achievements of the scholar of late antiquity are judged strikingly critical, but much material from his work is tacitly adopted. This suggests that the author of the new comment was competing with his predecessor and wanted to replace his font. Wilhelm, on the other hand, who probably did not see himself in such a pronounced competitive relationship with Calcidius, came to a more positive assessment. The philosopher and poet Bernardus Silvestris was one of the personalities of this time who were strongly influenced by Platonic natural philosophy . His cosmology and anthropology show the influence of Calcidius' analogy thinking. The epic De planctu Naturae (On the Lamentation of Nature) by Alanus from Insulis , written in the late 12th century, also contains ideas from the late antique Timaeus commentary.

The reception of the Platonic concept of justice formulated by Calcidius with the pair of terms iustitia naturalis and iustitia positiva was momentous . This concept was taken up in the 12th century by the legal philosophers who developed the doctrine of natural law . The text of Timaeus did not provide sufficient support for this, but the commentary of Calcidius did. There one found the core idea of natural law: Calcidius had interpreted the entire Timaeus as Plato's doctrine of natural justice and contrasted it with Politeia as the doctrine of “positive” justice created by man through law. According to his understanding, the law that has to apply among people is an outflow of the cosmic order, the laws of nature based on mathematical facts. This thought became one of the roots of the medieval and modern notion that the norm of man-made law is to be found in nature itself. This is particularly evident in the Summa Duacensis , a legal handbook from around 1200 , whose unknown author defined natural law with reference to the Timaeus . He understood the whole of creation as a legal order in which every creature is given a right by virtue of being created.

In the late 14th and 15th centuries, a new interest in Calcidius awoke with the development of Renaissance humanism , which first flourished in Italy. This can be seen in the number of manuscripts written at the time - at least 40, of which at least 28 were from Italy. Sometimes only the Timaeus translation was copied , sometimes only the commentary, sometimes both together. Most of Italy's major public and princely libraries, as well as many humanists, had copies. Francesco Petrarca (1304–1374) made notes in his copy that show his intense preoccupation with the work. The humanist Marsilio Ficino , later known as a translator and interpreter of Platonic dialogues , made a copy of the commentary himself as a young man in 1454, in which he made a plethora of notes on language use, content and sources. When he later created a new Latin translation of Timaeus , he did indeed use late antiquity, but the preparatory work of his predecessor was of little help, because his Latin did not meet the high standards of the humanists; therefore he only resorted to it occasionally. Ficino's friend Giovanni Pico della Mirandola (1463–1494) also had a copy of Calcidius' work, which he made notes.

Modern times

In 1520 the first edition of the Timaeus translation and the commentary appeared in Paris . The editor was the humanist Agostino Giustiniani (Augustine Justinianus), Bishop of Nebbio . In the dedication letter, Giustiniani was enthusiastic about the erudition and impartiality of Calcidius, who wrote so objectively that it was not even clear from his explanations whether he was a Christian or a Jew. Later, some scholars thought the interpreter of Plato was a Jew, others - including the philosopher Ralph Cudworth (1617–1688) and the philologist Johann Albert Fabricius (1668–1736) - a Christian. Fabricius brought out a new edition of the Timaeus translation and commentary in Hamburg in 1718 . The church historian Johann Lorenz von Mosheim put forward another hypothesis in a detailed study of the religious question in 1733 . He said that Calcidius was neither a Christian nor a Jew, nor was he a pure Platonist, but a pagan eclectic who had enriched his Platonic philosophy with Christian concepts.

In modern times, the performance of Calcidius has often been judged with disdain. It was widely believed that he was a mere compiler pulling together material from older literature. The verdict of the lack of originality meant that the question of his now lost sources came to the fore in research. In the third edition of his handbook on the history of Greek philosophy in 1881 , Eduard Zeller found that Calcidius' writing did not rise “above the character of dependent imitation”, and Bronislaus Switalski wrote in 1902 that “nothing independent should be expected from him”. Jan Hendrik Waszink stated in 1973 that the Timaeus commentary did not contain any personal interpretations or views of the author, but only material from his templates, the now lost writings of Porphyry, Adrastus and Origen. The original achievement of Calcidius consists in the structure of the whole and in the design, "which one cannot deny a certain merit". Goulven Madec ruled in 1989 that Calcidius had not "really come to his own doctrine"; its originality lies in the overall layout and the presentation for a Latin-speaking audience with a relatively closed philosophical terminology.

Far more positive judgment fell in 2008 by Peter Dronke out. He described the Timaeus Commentary as a unique and deeply individual product that had inspired extraordinary thinkers in their search for truth and an unconventional worldview for eight centuries. Calcidius encouraged intellectual freedom and open-ended research. The extraordinary importance of Calcidius' work for the reception of Plato in the Middle Ages is also emphasized in other ways. Until the middle of the 12th century, the Latin Timaeus was the only major Plato text available to scholars in Western and Central Europe, and it remained the most important for a long time afterwards. Until the 12th century, only the late antique commentary was decisive for its interpretation. Therefore, the influence of Calcidius on European intellectual history is estimated to be high.

In 2005, Ada Neschke-Hentschke paid tribute to the role of Calcidius in the history of natural law. She wrote that the distinction between natural and positive law, which is still common today, goes back to his Timaeus interpretation . The legal and legal-philosophical tradition that followed on from it was the determining factor in Western legal development.

Text editions and translations

- Béatrice Bakhouche (Ed.): Calcidius: Commentaire au Timée de Platon. 2 volumes, Vrin, Paris 2011, ISBN 978-2-7116-2264-1 (critical edition with French translation and detailed introduction; the second volume contains the editor's comment)

- Jan Hendrik Waszink (Ed.): Timaeus a Calcidio translatus commentarioque instructus (= Plato Latinus , Volume 4). 2nd, supplemented edition, Brill, London / Leiden 1975, ISBN 978-0-854-81052-9 (critical edition with detailed introduction)

- Claudio Moreschini (Ed.): Calcidio: Commentario al “Timeo” di Platone . Bompiani, Milano 2003, ISBN 88-452-9232-0 (Latin text of the Timaeus translation and the commentary based on Waszink's edition, but without the critical apparatus, and Italian translation)

literature

Overview representations

- Siegmar Döpp : Calcidius. In: Christoph Riedweg et al. (Ed.): Philosophy of the Imperial Era and Late Antiquity (= Outline of the history of philosophy . The philosophy of antiquity. Volume 5/3). Schwabe, Basel 2018, ISBN 978-3-7965-3700-4 , pp. 2327–2330, 2391–2393

- Goulven Madec: Calcidius. In: Reinhart Herzog (ed.): Restoration and renewal. The Latin literature from AD 284 to 374. CH Beck, Munich 1989, ISBN 978-3-406-31863-4 , pp. 356-358

- Gretchen Reydams-Schils: Calcidius. In: Lloyd P. Gerson (Ed.): The Cambridge History of Philosophy in Late Antiquity , Volume 1, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2010, ISBN 978-0-521-76440-7 , pp. 498-508

- Jan Hendrik Waszink: Calcidius . In: Reallexikon für Antike und Christianentum , Supplement-Liefer 10, Hiersemann, Stuttgart 2003, ISBN 3-7772-0243-6 , Sp. 283-3300

Investigations

- Stephen Gersh: Middle Platonism and Neoplatonism. The Latin Tradition , Volume 2, University of Notre Dame Press, Notre Dame 1986, ISBN 0-268-01363-2 , pp. 421-492 (detailed discussion of the teachings and their origins)

- Kathrin Müller: Visual appropriation of the world. Astronomical and cosmological diagrams in manuscripts of the Middle Ages. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2008, ISBN 978-3-525-36711-7 , pp. 29-92

- Gretchen J. Reydams-Schils: Meta-Discourse: Plato's Timaeus according to Calcidius . In: Phronesis 52, 2007, pp. 301-327

- Jan Hendrik Waszink: Studies on the Timaeus commentary by Calcidius , Volume 1: The first half of the commentary (with the exception of the chapter on the world soul). Brill, Leiden 1964 (no longer published)

Comments

- Jan den Boeft: Calcidius on Demons (Commentarius Ch. 127-136). Brill, Leiden 1977, ISBN 90-04-05283-6

- Jan den Boeft: Calcidius on Fate. His Doctrine and Sources. Brill, Leiden 1997 (reprint of the first edition from 1970), ISBN 90-04-01730-5

- Jacob CM van Winden: Calcidius on Matter. His Doctrine and Sources. A Chapter in the History of Platonism. Brill, Leiden 1965

reception

- Peter Dronke: The Spell of Calcidius. Platonic Concepts and Images in the Medieval West. SISMEL, Firenze 2008, ISBN 978-88-8450-270-4

- Paul Edward Dutton: Medieval Approaches to Calcidius. In: Gretchen J. Reydams-Schils (Ed.): Plato's Timaeus as Cultural Icon. University of Notre Dame Press, Notre Dame 2003, ISBN 0-268-03872-4 , pp. 183-205

Web links

Latin text

- Platonis Timaeus , text of the Latin translation and the commentary by Calcidius based on the edition by Johann Wrobel , Leipzig 1876

- Platonis Timaeus , text of the translation by Calcidius

- Timaeus , original Greek text in transcription , Latin translation of Calcidius and German translation

- Timaeus , the translation of Calcidius in the manuscript Digby 23 in the Bodleian Library , Oxford (12th century)

literature

Remarks

- ^ Jan Hendrik Waszink: Calcidius . In: Reallexikon für Antike und Christianentum , Supplement-Liefer 10, Stuttgart 2003, Sp. 283-3300, here: 283. See, however, the cautious statement by Paul E. Dutton: Medieval Approaches to Calcidius. In: Gretchen J. Reydams-Schils (ed.): Plato's Timaeus as Cultural Icon , Notre Dame 2003, pp. 183–205, here: 184 f.

- ↑ See Paul E. Dutton: Medieval Approaches to Calcidius. In: Gretchen J. Reydams-Schils (ed.): Plato's Timaeus as Cultural Icon , Notre Dame 2003, pp. 183–205, here: 186 f.

- ^ Jan Hendrik Waszink (Ed.): Timaeus a Calcidio translatus commentarioque instructus , 2nd, supplemented edition, London / Leiden 1975, pp. IX-XIV; Jan Hendrik Waszink: Calcidius . In: Reallexikon für Antike und Christianentum , Supplement-Liefer 10, Stuttgart 2003, Sp. 283–300, here: 284–286.

- ↑ Jan Hendrik Waszink (Ed.): Timaeus a Calcidio translatus commentarioque instructus , 2nd, supplemented edition, London / Leiden 1975, pp. XVI f .; Jan Hendrik Waszink: Calcidius . In: Reallexikon für Antike und Christianentum , Supplement-Liefer 10, Stuttgart 2003, Sp. 283–300, here: 286–289. On this cf. Hosius John Robert Martindale: The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire , Vol. 2, Cambridge 1980, p. 572.

- ^ Pierre Courcelle: Ambroise de Milan et Calcidius . In: Willem den Boer et al. (Ed.): Romanitas et Christianitas , Amsterdam 1973, pp. 45–53, here: 49.

- ↑ Christine Ratkowitsch: The Timaios translation of Chalcidius, a Plato christianus . In: Philologus 140, 1996, pp. 139–162, here: 141.

- ↑ Béatrice Bakhouche (ed.): Calcidius: Commentaire au Timée de Platon , Vol. 1, Paris 2011, pp. 8-13.

- ↑ Eckart Mensching: On the Calcidius tradition . In: Vigiliae Christianae 19, 1965, pp. 42–56, here: 55 f.

- ^ John Dillon: The Middle Platonists , London 1977, pp. 401 f., 408.

- ↑ Gretchen Reydams-Schils: Calcidius. In: Lloyd P. Gerson (Ed.): The Cambridge History of Philosophy in Late Antiquity , Vol. 1, Cambridge 2010, pp. 498–508, here: 498; Peter Dronke: The Spell of Calcidius , Firenze 2008, pp. 3–7. Cf. Pier Franco Beatrice: A quote from Origen in the Timaeus commentary by Calcidius . In: Wolfgang A. Bienert , Uwe Kühneweg (eds.): Origeniana Septima , Leuven 1999, pp. 75–90, here: 75–77.

- ^ Anna Somfai: The Eleventh-Century Shift in the Reception of Plato's Timaeus and Calcidius's Commentary . In: Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 65, 2002, pp. 1–21, here: 12; Gretchen Reydams-Schils: Calcidius Christianus? God, body and matter. In: Theo Kobusch , Michael Erler (eds.): Metaphysik und Religion , Munich 2002, pp. 193–211, here: 196–201, 204–209; Gretchen J. Reydams-Schils: Meta-Discourse: Plato's Timaeus according to Calcidius . In: Phronesis 52, 2007, pp. 301–327, here: 310.

- ↑ For example Pier Franco Beatrice: A quote from Origen in the Timaios commentary by Calcidius . In: Wolfgang A. Bienert, Uwe Kühneweg (eds.): Origeniana Septima , Leuven 1999, pp. 75–90, here: 77 and Christine Ratkowitsch: The Timaios translation of Chalcidius, a Plato christianus . In: Philologus 140, 1996, pp. 139-162.

- ^ So Claudio Moreschini: Il Commento al Timeo di Calcidio tra platonismo e cristianesimo . In: Maria Barbanti et al. (Ed.): ΕΝΩΣΙΣ ΚΑΙ ΦΙΛΙΑ. Unione e amicizia. Omaggio a Francesco Romano , Catania 2002, pp. 433-440; John Dillon: The Middle Platonists , London 1977, pp. 402, 408.

- ↑ Gretchen Reydams-Schils: Calcidius Christianus? God, body and matter . In: Theo Kobusch, Michael Erler (eds.): Metaphysik und Religion , Munich 2002, pp. 193–211, here: 209; Christina Hoenig: Timaeus Latinus: Calcidius and the Creation of the Universe. In: Rhizomata 2, 2014, pp. 80–110, here: 93–96.

- ↑ Claudio Moreschini (ed.): Calcidio: Commentario al “Timeo” di Platone , Milano 2003, p. VIII and note 2; Béatrice Bakhouche (Ed.): Calcidius: Commentaire au Timée de Platon , Vol. 1, Paris 2011, pp. 21, 120–124.

- ^ Calcidius, In Platonis Timaeum 7.

- ↑ See Paul E. Dutton: Medieval Approaches to Calcidius. In: Gretchen J. Reydams-Schils (ed.): Plato's Timaeus as Cultural Icon , Notre Dame 2003, pp. 183–205, here: 190 f .; Béatrice Bakhouche (Ed.): Calcidius: Commentaire au Timée de Platon , Vol. 1, Paris 2011, pp. 25-27.

- ^ Jan Hendrik Waszink: Calcidius . In: Reallexikon für Antike und Christianentum , Supplement-Liefer 10, Stuttgart 2003, Sp. 283–300, here: 289.

- ↑ Calcidius, In Platonis Timaeum 1–4 and 322. See Gretchen J. Reydams-Schils: Meta-Discourse: Plato's Timaeus according to Calcidius . In: Phronesis 52, 2007, pp. 301–327, here: 303–306.

- ↑ Kathrin Müller: Visuelle Weltaneignung , Göttingen 2008, p. 32 f.

- ↑ See Stephen Gersh: Middle Platonism and Neoplatonism. The Latin Tradition , Vol. 2, Notre Dame 1986, pp. 428-431; Béatrice Bakhouche (Ed.): Calcidius: Commentaire au Timée de Platon , Vol. 1, Paris 2011, p. 36 f.

- ↑ Stephen Gersh: Middle Platonism and Neoplatonism. The Latin Tradition , Vol. 2, Notre Dame 1986, p. 428.

- ↑ Jan Hendrik Waszink (Ed.): Timaeus a Calcidio translatus commentarioque instructus , 2nd, supplemented edition, London / Leiden 1975, pp. LXX – LXXXII, XC – XCV; Stephen E. Gersh: Calcidius' Theory of First Principles . In: Studia Patristica 18/2, 1989, pp. 85-92 and Middle Platonism and Neoplatonism. The Latin Tradition , Vol. 2, Notre Dame 1986, pp. 431 f .; Pier Franco Beatrice: A quote from Origen in the Timaeus commentary by Calcidius . In: Wolfgang A. Bienert, Uwe Kühneweg (eds.): Origeniana Septima , Leuven 1999, pp. 75–90, here: 88–90.

- ^ John Dillon: The Middle Platonists , London 1977, pp. 403 f .; Gretchen J. Reydams-Schils: Meta-Discourse: Plato's Timaeus according to Calcidius . In: Phronesis 52, 2007, pp. 301–327, here: 311–314; John Phillips: Numenian Psychology in Calcidius? In: Phronesis 48, 2003, pp. 132-151; Béatrice Bakhouche (Ed.): Calcidius: Commentaire au Timée de Platon , Vol. 1, Paris 2011, p. 38 f.

- ↑ Stephen Gersh: Middle Platonism and Neoplatonism. The Latin Tradition , Vol. 2, Notre Dame 1986, pp. 426 f.

- ^ Jan Hendrik Waszink: Calcidius . In: Reallexikon für Antike und Christianentum , Supplement-Liefer 10, Stuttgart 2003, Sp. 283–300, here: 286 f.

- ↑ Charlotte Köckert: Christian Cosmology and Imperial Philosophy , Tübingen 2009, pp. 229–237; Pier Franco Beatrice: A quote from Origen in the Timaeus commentary by Calcidius . In: Wolfgang A. Bienert, Uwe Kühneweg (eds.): Origeniana Septima , Leuven 1999, pp. 75–90; Stephen Gersh: Middle Platonism and Neoplatonism. The Latin Tradition , Vol. 2, Notre Dame 1986, pp. 429 f .; Béatrice Bakhouche: Calcidius (In Tim. Chap. 276-278) or Scripture in the Service of Philosophical Exegesis. In: Sydney H. Aufrère et al. (Ed.): On the Fringe of Commentary , Leuven 2014, pp. 345–359.

- ↑ Lukas J. Dorfbauer: Favonius Eulogius, the earliest reader of Calcidius? In: Hermes 139, 2011, pp. 376–394, here: 387. For details see Anna Somfai: Calcidius' commentary on Plato's Timaeus and its place in the commentary tradition: the concept of analogia in text and diagrams . In: Peter Adamson et al. (Eds.): Philosophy, Science and Exegesis in Greek, Arabic and Latin Commentaries , Vol. 1, London 2004, pp. 203-220, here: 208-213; on the astronomical diagrams see Bruce Eastwood, Gerd Graßhoff : Planetary Diagrams for Roman Astronomy in Medieval Europe, approx. 800–1500 , Philadelphia 2004, pp. 9–11, 17 f., 73–97.

- ^ John Dillon: Calcidius . In: Richard Goulet (Ed.): Dictionnaire des philosophes antiques , Vol. 2, Paris 1994, p. 156 f., Here: 157.

- ↑ Stephen E. Gersh: Calcidius' Theory of First Principles . In: Studia Patristica 18/2, 1989, pp. 85-92; Pier Franco Beatrice: A quote from Origen in the Timaeus commentary by Calcidius . In: Wolfgang A. Bienert, Uwe Kühneweg (eds.): Origeniana Septima , Leuven 1999, pp. 75–90, here: 76, 88 f .; Claudio Moreschini (Ed.): Calcidio: Commentario al “Timeo” di Platone , Milano 2003, pp. XVII – XIX, XXIV.

- ^ Calcidius, In Platonis Timaeum 243 and 246. See also Béatrice Bakhouche: La théorie de la vision chez Calcidius (IV e siècle) entre géométrie, médecine et philosophie. In: Revue d'histoire des sciences 66, 2013, pp. 5–31, here: 26–31.

- ↑ Gretchen J. Reydams-Schils: Meta-Discourse: Plato's Timaeus according to Calcidius . In: Phronesis 52, 2007, pp. 301–327, here: 306–309, 313 f., 325.

- ↑ On the relationship between Calcidius and Stoa, see Gretchen Reydams-Schils: Calcidius on God. In: Mauro Bonazzi, Christoph Helmig (eds.): Platonic Stoicism - Stoic Platonism , Leuven 2007, pp. 243-258, here: 256-258.

- ↑ Kathrin Müller: Visuelle Weltaneignung , Göttingen 2008, p. 89 f.

- ↑ Kathrin Müller: Visuelle Weltaneignung , Göttingen 2008, p. 90 f.

- ↑ Anna Somfai: Calcidius' commentary on Plato's Timaeus and its place in the commentary tradition: the concept of analogia in text and diagrams . In: Peter Adamson et al. (Eds.): Philosophy, Science and Exegesis in Greek, Arabic and Latin Commentaries , Vol. 1, London 2004, pp. 203-220, here: 208-219; Gretchen Reydams-Schils: Calcidius on the Human Soul . In: Barbara Feichtinger et al. (Ed.): Body and soul. Aspects of late antique anthropology , Munich 2006, pp. 95–113, here: 105–109; Heinrich Dörrie , Matthias Baltes : Platonism in antiquity , Vol. 6.1, Stuttgart-Bad Cannstatt 2002, pp. 367-369.

- ↑ See also Barbara Obrist: La cosmologie médiévale. Textes et images , vol. 1: Les fondements antiques , Firenze 2004, pp. 266-269.

- ^ Stephen Gersh: Concord in Discourse , Berlin 1996, pp. 129-138.

- ^ Bruce S. Eastwood: Plato and circumsolar planetary motion in the Middle Ages . In: Archives d'Histoire Doctrinale et Littéraire du Moyen Age 60, 1993, pp. 7–26, here: 9.

- ↑ Odile Ricoux: Les Mages à l'aube du chien . In: Rika Gyselen (Ed.): La science des cieux. Sages, mages, astrologues , Bures-sur-Yvette 1999, pp. 219-232, here: 220-222.

- ↑ Barbara Obrist: La cosmologie médiévale. Textes et images , Vol. 1: Les fondements antiques , Firenze 2004, pp. 126–129.

- ↑ Calcidius, Platonis Timaeus 40d.

- ↑ Béatrice Bakhouche: Anges et démons dans le Commentaire au Timée de Calcidius (IV e siècle de notre ère) . In: Revue des Études latines 77, 1999, pp. 260–275, here: 262–266, 271, 274 f .; Anna Somfai: Calcidius' commentary on Plato's Timaeus and its place in the commentary tradition: the concept of analogia in text and diagrams . In: Peter Adamson et al. (Ed.): Philosophy, Science and Exegesis in Greek, Arabic and Latin Commentaries , Vol. 1, London 2004, pp. 203–220, here: 215 f .; Anna Somfai: The nature of daemons: a theological application of the concept of geometrical proportion in Calcidius' Commentary to Plato's Timaeus (40d-41a). In: Robert W. Sharples , Anne Sheppard (eds.): Ancient Approaches to Plato's Timaeus , London 2003, pp. 129-142.

- ^ Jacob CM van Winden: Calcidius on Matter , Leiden 1965, p. 31.

- ↑ Gretchen Reydams-Schils: Calcidius Christianus? God, body and matter . In: Theo Kobusch, Michael Erler (eds.): Metaphysik und Religion , Munich 2002, pp. 193–211, here: 203 f .; Gretchen Reydams-Schils: Calcidius. In: Lloyd P. Gerson (Ed.): The Cambridge History of Philosophy in Late Antiquity , Vol. 1, Cambridge 2010, pp. 498–508, here: 506 f .; Peter Dronke: The Spell of Calcidius , Firenze 2008, pp. 25-30. Cf. Jacob CM van Winden: Calcidius on Matter , Leiden 1965, pp. 150–153.

- ↑ Gretchen Reydams-Schils: Calcidius Christianus? God, body and matter . In: Theo Kobusch, Michael Erler (eds.): Metaphysik und Religion , Munich 2002, pp. 193–211, here: 203 f.

- ↑ Gretchen Reydams-Schils: Calcidius on God. In: Mauro Bonazzi, Christoph Helmig (eds.): Platonic Stoicism - Stoic Platonism , Leuven 2007, pp. 243–258, here: 243–253; Jan den Boeft: Calcidius on Fate , Leiden 1997, pp. 13-17.

- ↑ Jan den Boeft: Calcidius on Fate , Leiden 1997, pp. 7, 28-30.

- ↑ Jan den Boeft: Calcidius on Fate , Leiden 1997, pp. 47-84.

- ^ Calcidius, In Platonis Timaeum 5-6. See Ada Neschke-Hentschke: The iustitia naturalis according to Platos Timaeus in the interpretations of the decretists of the XII. Century. In: Thomas Leinkauf , Carlos Steel (ed.): Plato's Timaios as a basic text of cosmology in late antiquity, the Middle Ages and the Renaissance , Leuven 2005, pp. 281–304, here: 291 f., 295.

- ↑ See Paul Edward Dutton: Illustre civitatis et populi exemplum: Plato's Timaeus and the Transmission from Calcidius to the End of the Twelfth Century of a Tripartite Scheme of Society. In: Mediaeval Studies 45, 1983, pp. 79–119, here: 83–86; Gretchen J. Reydams-Schils: Calcidius on the Human and the World Soul and Middle-Platonist Psychology. In: Apeiron 39, 2006, pp. 177-200, here: 189-191.

- ↑ For details see Massimiliano Lenzi: Anima, forma e sostanza: filosofia e teologia nel dibattito antropologico del XIII secolo , Spoleto 2011, pp. 4-19; Franco Trabattoni: Il problema dell'anima individuale in Calcidio. In: Fabrizio Conca et al. (Ed.): Politica, cultura e religione nell'impero romano (secoli IV-VI) tra oriente e occidente , Napoli 1993, pp. 289-304.

- ↑ James Hankins: The Study of the Timaeus in Early Renaissance Italy. In: James Hankins: Humanism and Platonism in the Italian Renaissance , Vol. 2, Rome 2004, pp. 93–142, here: 93 f.

- ^ Marion Lausberg: Seneca and Plato (Calcidius) in the preface to the Saturnalia of Macrobius. In: Rheinisches Museum für Philologie 134, 1991, pp. 167–191, here: 175–179.

- ↑ Lukas J. Dorfbauer: Favonius Eulogius, the earliest reader of Calcidius? In: Hermes 139, 2011, pp. 376-394; Jan Hendrik Waszink: The concept of time in the Timaeus commentary by Calcidius . In: Vivarium. Festschrift Theodor Klauser on his 90th birthday , Münster 1984, pp. 348–352, here: 349; Béatrice Bakhouche (Ed.): Calcidius: Commentaire au Timée de Platon , Vol. 1, Paris 2011, pp. 48–50.

- ↑ On the distribution of Calcidius manuscripts in Western and Central Europe see Eckart Mensching: Zur Calcidius-Übergabe . In: Vigiliae Christianae 19, 1965, pp. 42–56, here: 52–55.

- ^ Paul E. Dutton: Medieval Approaches to Calcidius. In: Gretchen J. Reydams-Schils (ed.): Plato's Timaeus as Cultural Icon , Notre Dame 2003, pp. 183–205, here: 193 f.

- ^ Anna Somfai: The Eleventh-Century Shift in the Reception of Plato's Timaeus and Calcidius's Commentary . In: Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 65, 2002, pp. 1–21, here: 6–8, 16–18; Bruce S. Eastwood: Calcidius's Commentary on Plato's Timaeus in Latin Astronomy of the Ninth to Eleventh Centuries . In: Lodi Nauta, Arjo Vanderjagt (ed.): Between Demonstration and Imagination , Leiden 1999, pp. 171–209, here: 187–194; Michel Huglo: Recherches sur la tradition des diagrammes de Calcidius. In: Scriptorium 62, 2008, pp. 185-230, here: 187-210.

- ^ Michel Huglo: La réception de Calcidius et des Commentarii de Macrobe à l'époque Carolingienne . In: Scriptorium 44, 1990, pp. 3–20, here: 5.

- ^ Anna Somfai: The Eleventh-Century Shift in the Reception of Plato's Timaeus and Calcidius's Commentary . In: Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 65, 2002, pp. 1–21, here: 5–7.

- ^ John Marenbon: From the circle of Alcuin to the School of Auxerre , Cambridge 1981, p. 57; Christine E. Ineichen-Eder: Theological and philosophical teaching material from the Alkuin circle. In: German Archive for Research into the Middle Ages 34, 1978, pp. 192–201, here: 199.

- ^ Anna Somfai: The Eleventh-Century Shift in the Reception of Plato's Timaeus and Calcidius's Commentary. In: Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 65, 2002, pp. 1–21, here: 18 f. Cf. Irene Caiazzo: Abbon de Fleury et l'héritage platonicien . In: Barbara Obrist (Ed.): Abbon de Fleury. Philosophy, sciences et comput near l'an mil , 2nd edition, Paris 2006, pp. 11–31, here: 23–31; Bruce S. Eastwood: Calcidius's Commentary on Plato's Timaeus in Latin Astronomy of the Ninth to Eleventh Centuries. In: Lodi Nauta, Arjo Vanderjagt (ed.): Between Demonstration and Imagination , Leiden 1999, pp. 171–209, here: 178–186.

- ^ Brussels, Bibliothèque Royale , Codex 9625-26. See Anna Somfai: The Brussels gloss. In: Danielle Jacquart, Charles Burnett (eds.): Scientia in margine , Genève 2005, pp. 139–169.

- ^ Anna Somfai: The Eleventh-Century Shift in the Reception of Plato's Timaeus and Calcidius's Commentary . In: Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 65, 2002, pp. 1–21, here: 8–15; Thomas Ricklin: Calcidius with Bernhard von Chartres and Wilhelm von Conches . In: Archives d'Histoire Doctrinale et Littéraire du Moyen Age 67, 2000, pp. 119–141, here: pp. 125 f. and note 32.

- ^ Paul Edward Dutton: Illustre civitatis et populi exemplum: Plato's Timaeus and the Transmission from Calcidius to the End of the Twelfth Century of a Tripartite Scheme of Society. In: Mediaeval Studies 45, 1983, pp. 79–119, here: 89–102.

- ^ Paul Edward Dutton: Material Remains of the Study of the Timaeus in the Later Middle Ages. In: Claude Lafleur (ed.): L'enseignement de la philosophie au XIII e siècle , Turnhout 1997, pp. 203–230, here: 204–206.

- ↑ See on the authorship Béatrice Bakhouche (ed.): Calcidius: Commentaire au Timée de Platon , Vol. 1, Paris 2011, p. 59; Peter Dronke: The Spell of Calcidius , Firenze 2008, pp. 107-116, 136-140.

- ↑ For details see Thomas Ricklin: Calcidius with Bernhard von Chartres and Wilhelm von Conches . In: Archives d'Histoire Doctrinale et Littéraire du Moyen Age 67, 2000, pp. 119-141; Peter Dronke: The Spell of Calcidius , Firenze 2008, pp. 107-136.

- ^ Paul Edward Dutton: Illustre civitatis et populi exemplum: Plato's Timaeus and the Transmission from Calcidius to the End of the Twelfth Century of a Tripartite Scheme of Society. In: Mediaeval Studies 45, 1983, pp. 79–119, here: 105–107; Peter Dronke: The Spell of Calcidius , Firenze 2008, pp. 141-160.

- ^ Paul Edward Dutton: Illustre civitatis et populi exemplum: Plato's Timaeus and the Transmission from Calcidius to the End of the Twelfth Century of a Tripartite Scheme of Society. In: Mediaeval Studies 45, 1983, pp. 79–119, here: 114–117.

- ↑ Ada Neschke-Hentschke: The iustitia naturalis according to Platos Timaeus in the interpretations of the decretists of the XII. Century. In: Thomas Leinkauf, Carlos Steel (ed.): Platon's Timaeus as a basic text of cosmology in late antiquity, the Middle Ages and the Renaissance , Leuven 2005, pp. 281–304, here: 291–296.

- ↑ Manuscript Milan, Biblioteca Ambrosiana , p. 14 sup.

- ↑ James Hankins: The Study of the Timaeus in Early Renaissance Italy. In: James Hankins: Humanism and Platonism in the Italian Renaissance , Vol. 2, Rome 2004, pp. 93–142, here: 93–95, 98, 105, 107 f .; James Hankins: Plato in the Italian Renaissance , 3rd edition, Leiden 1994, p. 474.

- ^ Johann Wrobel: Platonis Timaeus interprete Chalcidio , Frankfurt 1963 (reprint of the Leipzig edition 1876), p. III f .; Bronislaus W. Switalski: Des Chalcidius commentary on Plato's Timaeus , Münster 1902, p. 3.

- ^ Johann Wrobel: Platonis Timaeus interprete Chalcidio , Frankfurt 1963 (reprint of the Leipzig edition 1876), pp. X – XII; Bronislaus W. Switalski: Des Chalcidius commentary on Plato's Timaeus , Münster 1902, pp. 3–5. See Jan Hendrik Waszink: Calcidius . In: Reallexikon für Antike und Christianentum , Supplement-Liefer 10, Stuttgart 2003, Sp. 283–300, here: 284.

- ↑ See Eginhard P. Meijering: Mosheim on the Difference between Christianity and Platonism . In: Vigiliae Christianae 31, 1977, pp. 68-73.

- ^ Eduard Zeller: The philosophy of the Greeks in their historical development , part 3, division 2, 3rd edition, Leipzig 1881, p. 855 f.

- ^ Bronislaus W. Switalski: Des Chalcidius commentary on Plato's Timaeus , Münster 1902, p. 13, cf. P. 8.

- ^ Jan Hendrik Waszink: Calcidius . In: Reallexikon für Antike und Christianentum , Supplement-Liefer 10, Stuttgart 2003 (first published in 1973), Sp. 283-300, here: 296.

- ^ Goulven Madec: Calcidius. In: Reinhart Herzog (ed.): Restoration and renewal. The Latin literature from 284 to 374 AD , Munich 1989, pp. 356–358, here: 357.

- ↑ Peter Dronke: The Spell of Calcidius , Firenze 2008, pp. IX f., XIV – XVI, 33 f.

- ↑ Jan Hendrik Waszink: Calcidius . In: Reallexikon für Antike und Christianentum , Supplement-Liefer 10, Stuttgart 2003, Sp. 283–300, here: 296 f.

- ↑ Ada Neschke-Hentschke: The iustitia naturalis according to Platos Timaeus in the interpretations of the decretists of the XII. Century. In: Thomas Leinkauf, Carlos Steel (ed.): Plato's Timaios as a basic text of cosmology in late antiquity, the Middle Ages and the Renaissance , Leuven 2005, pp. 281–304, here: 291 f., 295.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Calcidius |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Chalcidius |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | late antique scholar and philosopher |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 4th century |

| DATE OF DEATH | 4th century or 5th century |