The castle in the sky

| Anime movie | |

|---|---|

| title | The castle in the sky |

| Original title | 天空 の 城 ラ ピ ュ タ |

| transcription | Tenku no Shiro Rapyuta |

| Country of production |

|

| original language | Japanese |

| Publishing year | 1986 |

| Studio | Studio Ghibli |

| length | 124 minutes |

| Age rating |

FSK 6 JMK 10 |

| Rod | |

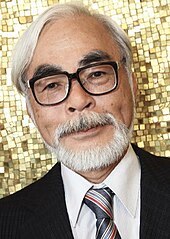

| Director | Hayao Miyazaki |

| script | Hayao Miyazaki |

| production | Isao Takahata |

| music | Joe Hisaishi |

The Castle in the Sky ( Japanese 天空 の 城 ラ ピ ュ タ , Tenkū no Shiro Rapyuta ) is an anime by Hayao Miyazaki that premiered in Japan in 1986. It is the first film by Studio Ghibli .

action

The young orphan Sheeta has lived alone in her hut in the mountains since the death of her parents. She inherited a necklace with a gemstone from her parents. The mysterious Musca, a government agent, kidnaps her on an airship with the help of the army . When this is attacked by the air pirate Dora and her sons, Sheeta climbs out of a window and falls into the depths. Since her stone has the strength to make her float, she ends up unconscious in the arms of Pazu, who is also an orphan and works for the miners of a mining town. He is looking for Laputa , a hidden city in heaven that his late father claims to have seen.

When the pirates appear, Pazu and Sheeta flee. On the run, they also meet the army and the agents, so that they eventually retreat into the mines. There they learn from an old miner that Sheeta's stone is a flying stone from a lost culture: Laputa. Sheeta says that she is descended from the royal family and the stone shows that she is the heir to the throne. On their way back to the mining town, the two friends are picked up by the army, which takes them to a fortress. Musca wants to use Sheeta to find Laputa and tries to win her over. Pazu is released for her sake and returns to his house. There he meets pirates again, whom he joins to save Sheeta.

During Pazu's absence, Sheeta accidentally awakens a robot that fell to earth from Laputa and was kept in the fortress. He wants to help her and show her the way to Laputa, but causes destruction in the enemy fortress. Sheeta can escape together with Pazu and the pirates, but Musca gets to Sheeta's stone, which shows him the way to Laputa. He also sets out with the army. Both groups reached Laputa by airships. Pazu and Sheeta arrive first and are blown away by the wonderful gardens, nature and peacefulness. There doesn't seem to be any humans, but there is a peaceful robot who lovingly takes care of the animals and plants.

Musca and the army also arrive soon and take the pirates prisoner. The secret agent, who also turns out to be a descendant of the original inhabitants of Laputa, uses the stone to open a secret gate and take control of the flying city. With Sheeta as a hostage at his side, he kills the soldiers and wants to usurp world domination with Laputa's powerful weapons . However, Sheeta and Pazu manage to overpower him and speak the formula of destruction. The core of the city is destroyed and Musca tears down. You fly away on a glider while the upper part of Laputa, the peaceful city that was protected from destruction by a huge tree, drifts further and further into the sky.

Emergence

The film was the first by Studio Ghibli, founded in 1985 . The foundation was possible after the success of Nausicaä from the Valley of the Winds in 1984 and was done with further financial support from Tokuma Shoten . Now more films were to be made with the same team.

The 124 minute long film was made from July 15, 1985 to July 23, 1986. 69,262 pictures were drawn and 381 different colors were used. In preparation for the film shoot, Miyazaki traveled to Great Britain with other Ghibli employees. The scenery was heavily influenced by landscapes in south Wales , which the team visited at the time of the miners' strike in the 1980s: Hayao Miyazaki witnessed the strikes in 1984 and visited the region again in 1986 to work on the film. He was impressed by the struggle of the miners for their work and the strength of their community and incorporated this into the portrayal of Pazu's village. The artistic director was Nizo Yamamoto . Katsuya Kondo , who later became known as a character designer in films such as Kumo no yō ni Kaze no yō ni or Whisper of the Sea , worked with the keyframe animation . The executive producer was Isao Takahata , who took on this role for the first time in his career.

As in almost all films, the music for the film was composed by Miyazaki's Joe Hisaishi . He uses a classical western orchestra as well as Japanese instruments. In addition, the film also has many segments without music, in which only noises such as the rustling of the rotor blades can be heard. For the American dubbed version, which Disney produced, Joe Hisaishi was commissioned in 1999 to extend the 37-minute film music to 90 minutes and to re-record it with a symphony orchestra .

Film analysis

Film technical means

The backgrounds are often worked out in detail. The title sequence, which shows the story of Laputa, has a distinctly different style than the rest of the film. The pictures are woodcut-like and kept in sepia tones . This will give you the appearance of old prints. The style is based on illustrations for the books Jules Verne.

Analogous to the Japanese reading direction from right to left, the right image space often takes on a special meaning in film. The important plot developments and the protagonists can often be seen on the right in the picture ( cadrage ). For example, in a gliding scene in the film, a diagonal appears from top right to bottom left, which is similar to the reading direction of manga . To create an illusion of spatial depth, Miyazaki often uses the sliding of the picture planes against each other, especially the clouds, as well as the reduction or enlargement of objects. This creates the impression that something is moving relative to the viewer without the viewer moving himself. The movement of the flying machines is also mostly a glide, whereby inclined angles always convey the influence of gravity or the wind and the machines do not seem completely detached from everything.

A wide camera angle is often used, in which the figures can sometimes only be seen as silhouettes . In the case of close-up settings, however, a lot of emphasis is placed on details that were previously hidden. The camera often wanders over unimportant things and makes use of an atmospheric staging, which makes the film very different from western animation films. The shot-reverse shot technique is also often used, for example in dialogues. In contrast to the calm poetic scenes, there are also many action scenes that are cut quite slowly compared to later conditions. A parallel montage often gives the action more dynamism.

Content influences and inspiration

The Japanese title of the film is an allusion to the satirical work Gulliver's Travels by the English writer Jonathan Swift (1667–1745). In the third book in the series, the ship's doctor Lemuel Gulliver arrives at the flying island of Laputa , which is kept in suspension and moved with the help of a large magnetic stone and whose inhabitants have devoted themselves to strange and senseless sciences. In addition to Gulliver's travels , Miyazaki was also inspired by an episode from a manga he read in his childhood: Fukushima Tetsuji's Sabaku no Maō . This episode was about a magical stone that gave its owner the ability to fly. Miyazaki brought up this story in such a way that he wanted to make a film about a magic stone himself. The working title of the film was therefore The Young Pazu and the Secret of the Floating Stone . He also worked on a concept for a television series in the 1970s that would combine Jules Verne's journey around the earth in 80 days and 20,000 leagues under the sea . Miyazaki then implemented ideas from this in his series Mirai Shōnen Conan from 1978, which was based on Alexander Keys The Incredible Tide and later incorporated them into The Castle in Heaven . The first concept was that of a typical adventure story about a boy. However, this changed in the course of further elaboration to a more differentiated story with two protagonists. The television series The Power of the Magic Stone by the Gainax studio later emerged from the same original concept . Another source and inspiration for the story of a magic stone or pendant and for its wearer Sheeta was the film Taiyō no Ōji: Horusu no Daibōken , Isao Takahata's directorial debut from 1968, in which Miyazaki had animated some scenes. The heroine of the film wears a magic pendant that she is controlled and has to free herself from. The weapons of mass destruction from an ancient civilization and how they are dealt with in the Castle in Heaven were already a major theme in Miyazaki's 1978 television series Mirai Shōnen Conan . Finally, the manga version of Nausicaä from the Valley of the Winds , which Miyazaki created parallel to the castle in the sky , features a stone that can be used to activate weapons.

As is often the case in his films, Miyazaki chose an apocalyptic or premodern world for the location of the action instead of modern Japan, here one in which industrialization is not yet over: the film takes place in a world reminiscent of the Victorian era . When describing the technical elements, Miyazaki oriented himself towards authors of the 19th century such as Jules Verne . The name Sheeta goes back to Princess Sita from the Indian epic Ramayana. The robots appearing in the film were designed by Miyazaki himself. Similar robots appeared in an episode of his anime series Lupine in 1980 . Back then, Miyazaki was inspired by an episode of the Fleischer Studios Superman animated series from 1941. You can also see fox squirrels on the island that appeared in Nausicaä from the Valley of the Winds .

For Thomas Lamarre, the similarities with other works by Hayao Miyazaki show that over a long period of his work he has repeatedly dealt with the same topics - the handling of weapons via magical objects - and their similar disguise in fantastic worlds. The castle in the sky is the highlight of this occupation, in which many elements that have already been tried and tested come together. At the same time, the film marks the emergence of a characteristic style of Studio Ghibli from all these elements and Miyazaki's departure from the topics mentioned. In this form they do not appear again later in his work, and Miyazaki himself said he had finished with adventure film as a genre. According to Lamarre, Miyazaki has always dealt critically with the genre by questioning the pursuit of treasure and magical powers - as in this film - so that his films become anti-adventurous adventure films. This also expresses Miyazaki's relationship to technology and nature.

People, nature and technology

Miyazaki often addresses the relationship between people, nature and technology in his films. It reflects the increased environmental awareness of Japanese society , which was triggered by the consequences of the rapid industrial growth after the Second World War . Due to extreme environmental pollution , Japan developed into an international role model in environmental protection until the 1980s . Thomas Lamarre also mentions this theme in The Castle in Heaven as one of the three main elements of the film. He relates the film to Miyazaki's views on the relationship between humans and nature and technology and compares it with Paul Virilio's pessimistic worldview , in which the constant pursuit of acceleration leads to ever greater destruction, and Heidegger's philosophy . Like Virilios, Miyazaki represents a pessimistic expectation of the future in the film, in which progress will turn against people, but like Heidegger he develops a deterministic understanding of technology not as a problem with solutions, but as a fact that affects behavior and perception who has. This worldview is expressed in particular in the title sequence, in which the rise and fall of Laputa's civilization is shown. The exact background of this story and the origin of the blue stones remain unclear, so that the story of Laputa takes on the character of an epic or myth of technological rise and fall. On one level, the film first shows how the circumstances are dealt with as problems with solutions: The organization looking for Laputa's weapons appears as a clearly evil organization and their access to the weapons is prevented by their destruction. In the fact that the weapon has to be destroyed instead of being placed under the control of another, good authority, Miyazaki's view shows that such an authority for weapons cannot exist. The solution to the problem is not the victory over the bad guys, as it is shown in many adventure stories, but the destruction of the weapon. Instead of the movements into the depths of space that are common in western animation and cinema, the lateral movement occurs more frequently in front of a naturalistic background and the depth effect is created by different movements in the foreground and background. In the staging of the flying island, when the children discover it, they are invited to contemplate it, not to intrude and plunder. Lamarre calls this animation principle, which distinguishes itself from cinema that looks ballistic and strives for speed and which Virilio criticizes, "animetism". He sees the Cel levels floating above the background as representative of Miyazaki's alternative concept of a decelerated society. With this and with the way his protagonists deal with technology, Miyazaki shows that a different relationship to technology is possible. Because Miyazaki does not oppose any technology; instead, the depictions of machines, especially airplanes, show his enthusiasm for technology.

Like many of Miyazaki's films, The Castle in Heaven is heavily influenced by the Shinto religion, which is practiced almost exclusively in Japan . The basic idea of harmony in Shintō states that one should treat the natural human environment carefully and use technology sensibly. However, the film shows that the unity of man, nature and technology has not succeeded. People are in a time of great social and technical change. The working class has to bow to these changes and is exploited by large industries . In one scene, a small poster hints at the fierce fighting between the workers and the exploitative mine owners. However, there is also the other side, where machines were built according to nature's example. The ornithopters used by the air pirates are very similar to dragonflies . Towards the end of the film, a robot also appears that lovingly takes care of gardens and animals. Thomas Lamarre sees Miyazaki's rejection of high technology (such as jets) and a preference for more unusual technology in the aircraft, which are inspired by nature and usually appear bulky or not at all airworthy. The most successful machines in the film or those of the heroes are also the simplest and smallest.

Analysis of the characters

As the third important motif of the film, Lamarre names the youthful energy of the two protagonists, which drives the plot forward and turns the action for the better. Both are still asexual, but shortly before puberty, and develop a very close but not yet sexual relationship with each other. He recognizes clear differences in the portrayal of both characters, which correspond to the respective gender roles. Like other boys in Miyazaki's films, Pazu is purposeful, ambitious, active, and interested in technology. He strives for concrete goals and is shown again and again interacting with the world around him and exerting great exertion - which is shown in the animation through strong, exaggerated poses of his character. The girl Sheeta, on the other hand, is less determined, but plays a central role because of her magical and technical stone. She inherited her power and burden from her ancestors, not earned them like Pazu. This also symbolizes Miyazaki's understanding of technology as a given condition instead of a skill. In the course of history she is always driven by the events and object of the actions of others, similar to her stone. In the animation of her character, her role is shown by her light, massless appearance. Two gender roles are represented in the film: boys interact directly with the objects in their environment and deal with technology as with problems with solutions; Girls act indirectly, magically and experience technology as a condition of their environment. This also makes them the key to a freer relationship with technology and the redeemer - similar to Nausicaä . In the end, it is Sheeta who becomes active, teaches Pazu the words of destruction and frees herself from the stone, from Laputa and the dangers associated with it. At the same time, she frees herself from her passive gender role. Ultimately, Miyazaki's portrayal of and criticism of gender roles remains contradictory, according to Lamarre: On the one hand, he breaks with the role models in the end, on the other hand, they are only established and consolidated over large parts of the film and are a central part of the plot.

In the course of the plot, the pirate Dora takes on a mother role for the two orphans Pazu and Sheeta, according to Patrick Drazen.

Miyazaki mainly uses classic film techniques such as exaggerated slapstick scenes and the ballistic perspective for comical, relaxed scenes in which men behave in a clichéd and excessively violent manner. According to Lamarre, behind this is a criticism of precisely these male role models. The Castle in the Sky is the last film in which Miyazaki makes use of these techniques and marks the change to a representation focused on picturesque landscapes and backgrounds and away from one focused on movement. According to Lamarre, this also indicates a change in the target group - from fans or otaku to the general public.

As in Miyazaki's other films, the element of flying (such as Porco Rosso and Kiki's small delivery service ) and the criticism of martial militarism (such as in Howl's Moving Castle or Nausicaä from the Valley of the Wind ) combine great importance. According to Susan Napier, Miyazaki shows hope and the possibility of change and freedom in flying as a symbol, as well as in the two protagonists' willingness to sacrifice themselves for a better world in the end (to crash with the island). Even if, unlike in other of his films, in Das Schloss im Himmel it is not primarily the girl or young woman who flies, in Miyazaki flying also stands for the strength and independence that the protagonist achieves.

synchronization

The film was only dubbed in German in 2003 at FFS Film- und Fernseh-Synchron in Munich . Florian Kramer wrote the dialogue book and Frank Lenart directed the dialogue .

In the Japanese version, Megumi Hayashibara also plays a small role, which was the debut of the later very successful speaker.

| role | Original speaker | German speaker |

|---|---|---|

| Sheeta | Keiko Yokozawa | Natalie Loewenberg |

| Pazu | Mayumi Tanaka | Nico Mamone |

| Muska | Minori Terada | Claus-Peter Damitz |

| Dora | Kotoe Hatsui | Ilona Grandke |

| Muoro | Ichirō Nagai | Manfred Erdmann |

| Louis | Yoshito Yasuhara | Claus Brockmeyer |

| Henri | Sukekiyo Kameyama | Jens Kretschmer |

| Charlie | Takumi Kamiyama | Christoph Jablonka |

| Duffi | Machiko Washio | Thorsten Nindel |

| Pomu | Fujio Tokita | Werner Uschkurat |

| grandmother | Kotoe Hatsui | Ruth Küllenberg |

publication

The film was released in Japanese theaters on August 2, 1986. It was shown on a cinema ticket along with two episodes of the television series Sherlock Hound , also by Miyazaki. The distribution was carried out by Tōei . After the film was released, the film history was published as a two-volume novel. Osamu Kameoka wrote the 172-page books and Miyazaki illustrated them with color pictures.

The Japanese production company Tokuma had a dubbed version made for publication in several English-speaking countries. The premiere of the film in this version in the USA took place in March 1989 in Philadelphia, then under the title Laputa: The Castle in the Sky . It was the first theatrical title from the fledgling anime distributor Streamline Pictures . Further publications in European and North American countries followed in the late 1990s and early 2000s by Disney, who had acquired the rights to the Ghibli films. A new English dubbed version was also created and the music revised. Because the term “La puta” means “whore” in Spanish (it was intentionally used as an offensive term by Swift) and this could have caused problems with the title in Spanish-speaking regions, the Japanese film name has now become Castle in in the United States the Sky and in Mexico and Spain shortened to El castillo en el cielo (each meaning “[The] castle in the sky”; in the Spanish versions the castle is called “Lapuntu”). Other countries also adopted the abbreviated version, although the word "Laputa" has no meaning of its own there.

Universum Film released the film in German cinemas almost 20 years after its premiere on June 8, 2006. The film started one day later in Austria. On November 13, 2006, Das Schloss im Himmel was released on DVD in Germany on the Universum Anime label. There is the standard version with just the film (1 DVD) and the special edition with the film and bonus material (2 DVDs). The image transmission of both versions is in anamorphic widescreen (16: 9) and the sound in Dolby Digital 2.0 (stereo). The bonus DVD of the Special Edition contains the storyboard for the complete film, the original Japanese trailer and commercial for the film, the history of the castle, the original Japanese opening and ending, information about the marketing for the cinema release and the Studio Ghibli as well as five exclusive ones Trading cards. On July 8, 2011, the film was finally released on the high-resolution Blu-ray medium. The distributor in Germany is again Universum Film GmbH.

reception

Audience reaction and success

With an audience of 774,271, the film was less successful than Miyazaki's previous work, Nausicaä from the Valley of the Winds , but was also considered commercially successful and enabled the animation studio Ghibli, founded in 1985, to produce more anime films. It was followed by My Neighbor Totoro and The Last Fireflies in 1988.

In 2013, the number of visitors to Sarushima Island doubled after the island's resemblance to the Laputa featured in the film became known.

While the film was seen over 900,000 times when it opened in France in 2003, it only found 20,690 viewers in German cinemas in 2006.

Reviews

Critics received it almost entirely positively and praised, among other things, that the film did not have a typical good-evil scheme. It is not a typical children's film, but surprisingly grown up. In 1986 the film received the Ōfuji Noburō Prize at the Mainichi Eiga Concours and the Anime Grand Prix of Animage magazine . In a 2007 survey by the Japanese Ministry of Culture, the film came in second place among the most popular animated films and third place among the most popular animated films and series.

Fred Patten counts The Castle in Heaven among the 13 most remarkable anime films from 1985 to 1999. The first dubbed version was controversial and the head of the American publisher, Carl Macek, named it appropriately, but crudely implemented. The later revision of the sound of Disney was also controversial. However, this revision was also approved by Studio Ghibli. The Anime Encyclopedia mentions a similarity of the conceptual content to Miyazaki's films Nausikaä and Princess Mononoke : the groups of characters quarrel over the remains of an ancient order, only to ultimately destroy it. As in the other films, he shows a credible character drawing. According to Thomas Lamarre, it is precisely that Miyazaki shows both a technology-critical attitude and enthusiasm for (flight) technology in the film. Because of the more complex world and characters, the film is aimed at older children and adults.

The film was also received very positively by critics in Germany. The lexicon of international films praises the anime as a “multi-layered, splendidly designed cartoon fairy tale”, which is “initially told as an adventure film, in the second half as a science fiction film”. "A masterpiece of animation film that testifies to the creativity and timeless 2D animation art of its creator Hayao Miyazaki." The children and youth film center emphasizes the unmistakable cosmos of film, which has arisen from various influences. “As in all of Hayao Miyazaki's other anime, the main characters form an illustrious ensemble with unusual and original characters. The Castle in Heaven is a film with artistic aspirations and high entertainment value for all generations. "

Hanns-Georg Rodek writes in Die Welt on the occasion of the German cinema premiere in 2006: “The miracle of the castle in the sky consists in the fact that Miyazaki has succeeded in creating a seamless work of art, also homogenized by a hellish narrative pace that reveals the incredible wealth of detail (if you can in the cinema), but never wallows in it. ”In the Frankfurter Rundschau, Daniel Kothenschulte notes that one is amazed“ what qualities the director Miyazaki possesses apart from the fantastic. In a few seconds he can charge a typically English landscape with the pathos of early Technicolor dramas. ”The German trendy magazine Animania praises Miyazaki's deviation from the usual good-evil scheme and differentiated characters, such as the pirates, whose role changes in the course of the plot changes, like the two protagonists who “complement each other and grow together”. The story expresses Miyazaki's critical, but not fundamentally negative, attitude towards technology and progress. "The director's enthusiasm for technology shines through in the detailed depiction of the incredible aircraft and the impressive steam engines." The film develops a scheme that is to become Ghibli's trademark: "A strong story that is both enchanting and awake." the film is animated in a high quality, the dubbing of the German version is appropriate to the classic. On the occasion of its premiere in the cinema, the manga scene describes the German translation as very successful despite a few minor inaccuracies and freedoms. The “beautiful and somewhat naive film” is still just as impressive and fascinating even 20 years after it was made. The film is even friendlier and less harsh than some of Miyazaki's later films, the magazine said in an earlier review. It shows the problems of early industrialization without "annoying with the raised index finger", remains child-friendly and contains a lot of slapstick and exaggeration. This shows the influence of Miyazaki's Lupine film The Castle of Cagliostro . The style still shows a very clear similarity to the Heidi anime series. The combination of Miyazaki's narrative and film counting techniques, which have already been tried and tested, is also highlighted by the Animania . According to the manga scene , the film is gripping, technically outstanding and offers a timeless story.

literature

- Thomas Lamarre: The Anime Machine. A Media Theory of Animation . University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis 2009, ISBN 978-0-8166-5154-2 , pp. 38-42, 45-63, 78-85, and the like. a.

- Helen McCarthy: Hayao Miyazaki, Master of Japanese Animation: Films, Themes, Artistry . Stone Bridge Press, Berkeley, 1999.

Web links

- Castle in the Sky at theInternet Movie Database(English)

- Information on the German version from Universum Film

- Castle in the Sky at Rotten Tomatoes (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Age rating for The Castle in Heaven . Youth Media Commission .

- ↑ a b c d Patrick Drazen: Anime Explosion! - The What? Why? & Wow! of Japanese Animation . Stone Bridge Press, 2003, pp. 262f.

- ↑ a b c website with background information from the Ghiblink team

- ↑ a b Press release of Universum Film on The Castle in Heaven (Word file; 2.2 MB)

- ↑ a b c d e Jonathan Clements, Helen McCarthy: The Anime Encyclopedia. Revised & Expanded Edition . Stone Bridge Press, Berkeley 2006, ISBN 1-933330-10-4 , pp. 91 .

- ↑ David Gordon: Studio Ghibli: Animated Magic . Hackwriters.com. May 2006. Retrieved December 30, 2008.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Lamarre, 2009, pp. 55–63.

- ↑ a b c d e AnimaniA 11/2006, pp. 20-24.

- ↑ a b c d Lamarre, 2009, pp. 47–54.

- ↑ a b c d Film booklet from the Federal Agency for Civic Education on The Castle in Heaven (PDF; 1.6 MB) by Stefan Stiletto and Holger Twele

- ↑ a b c Thomas Lamarre : The Anime Machine. A Media Theory of Animation . University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis 2009, ISBN 978-0-8166-5154-2 , pp. 20th f., 39-40, 42 .

- ↑ Lamarre, 2009, pp. 74f.

- ↑ Lamarre, 2009, pp. 55f.

- ^ A b Susan J. Napier: Anime from Akira to Princess Mononoke: Experiencing Contemporary Japanese Animation . Palgrave 2001. pp. 123f.

- ↑ Thomas Lamarre : The Anime Machine. A Media Theory of Animation . University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis 2009, ISBN 978-0-8166-5154-2 , pp. 42, 44 .

- ↑ a b Lamarre, 2009, pp. 55, 61f.

- ↑ Lamarre, 2009, pp. 91f, 95.

- ↑ Lamarre, 2009, p. 214.

- ↑ Lamarre, 2009, pp. 78-85.

- ↑ Patrick Drazen: Anime Explosion! - The What? Why? & Wow! of Japanese Animation . Stone Bridge Press, 2003, p. 138.

- ↑ Lamarre, 2009, p. 109.

- ^ Susan J. Napier: Anime from Akira to Princess Mononoke: Experiencing Contemporary Japanese Animation . Palgrave 2001. p. 138.

- ↑ German synchronous index: German synchronous index | Movies | The castle in the sky. Retrieved March 6, 2018 .

- ↑ Trish Ledoux, Doug Ranney: The Complete Anime Guide . Tiger Mountain Press, Issaquah 1995, ISBN 0-9649542-3-0 , pp. 190 .

- ↑ Yukiko Oga: Fame for a tiny island that evokes images of Hayao Miyazaki's masterpiece. (No longer available online.) In: The Asahi Shimbun. May 4, 2015, archived from the original on March 4, 2016 ; accessed on August 12, 2015 .

- ↑ The Castle in Heaven at Lumiere, a database for cinema attendance in Europe

- ↑ Film review on filmstarts.de by Christoph Petersen

- ↑ Top 100 Animations . Agency for Cultural Affairs . 2007. Archived from the original on February 10, 2007. Retrieved March 15, 2009.

- ↑ Fred Patten: Watching Anime, Reading Manga - 25 Years of Essays and Reviews . Stone Bridge Press, 2004. p. 125.

- ↑ Carl Macek: ANN Cast Episode 23 . Anime News Network. Retrieved January 11, 2014: “We didn't dub it. Streamline didn't dub it. And I told the people at Tokuma Shoten that I thought the dubbing was marginal on Laputa and I thought that it could be a better product if they had a better dubbing ... To me, there's a certain element of class that you can bring to a project. Laputa is a very classy film, so it required a classy dub and the dub given to that particular film was adequate but clumsy. I didn't like it all ... It's not something that I appreciated intellectually as well as aesthetically. "

- ↑ Tenkuu no Shiro Rapyuta . The Hayao Miyazaki Web. Retrieved December 30, 2008.

- ↑ The Castle in Heaven. In: Lexicon of International Films . Film service , accessed March 2, 2017 .

- ↑ The Castle in Heaven . Top video news. Publisher: Children's and Youth Film Center on behalf of the BMFSFJ .

- ^ Film review by Hanns-Georg Rodek : The Second Destruction of Paradise , June 8, 2006, Die Welt

- ↑ Daniel Kothenschulte : What Heaven Permits . June 8, 2006, Frankfurter Rundschau .

- ↑ Manga scene No. 33, p. 21.

- ↑ a b Manga scene No. 14, p. 21.