The wild danger

The wild danger is a 400 meter long section of rock with a steep gradient in the mountain range of the Middle Rhine . It is located at the Rhine kilometer 544.7 between the cities of Bacharach and Kaub and the Rhine islands of Bacharacher and Kauber Werth . As a result of expansion measures in the 19th and 20th centuries, the wild danger lost the character of a rapids , which was one of the most difficult stretches of river to pass for Rhine shipping after the Binger Loch .

Surname

The name The wild danger (more rarely: The wild vehicle ) is documented for the year 1410. It is one of the waterfield names that were coined by boatmen and fishermen; Danger is traced back to the Middle High German gevoere for “place where it is dangerous”. In the past, a larger section of the Rhine between Binger Loch and Kaub, in which the Count Palatinate exercised rights near the Rhine , was called a wild vehicle . For the art historian Horst Johannes Tümmers, the “sound and name” of danger spots such as the wild danger “still indicate the respect” “which the boatmen once paid them”.

geography

After entering the Rhenish Slate Mountains near Bingen , the Rhine runs around 13 kilometers in a north-westerly direction to Bacharach. The river bed in the area of Bacharach and Kaub is formed by Hunsrück slate, which is only covered by small deposits if the river is wider than average or in places with little current. The individual layers of the slate are differently resistant, so that before the expansion there were numerous rock peaks and high rock banks in the river bed.

A good kilometer above Bacharach is one of the shallows of the Rhine , the Lorchhauser Grund , a rocky reef covered with sand. Before the expansion work, it stretched downstream to Bacharach and the Bacharacher Leyen rock group . Across from Bacharach, on the Wirbelley , the Rhine turns its course in a sharp right curve to the north. Shortly below Bacharach, to the left of the main stream, is the Bacharacher Werth , a river island made up of Hunsrück slate. The arm of the river lying between the island and the left bank is called the Hahnen ; in it there are several rocks like the Mühlenleyen and the thief stones . Also in the main stream downstream of the Wirbelley there were a number of rocks before the expansion, such as the large and small altar stones , the scout , the gallows lily or the fins tear .

The main stream divides north of the Bacharacher Werth : the actual wild danger was in the middle of the 19th century an almost 25 meter wide, relatively flat channel with a rapid current in an area with numerous rock banks and reefs. The higher rocks included the Weinsteinleyen , Weinsteinbrau , Wegsteine, and Kohley . The Wild Hazard crossed the river bed and joined the Hahnen on the left bank . Above the wild danger, the Kauber Wasser branched off to the right , which turned into a left curve. In it were other rocks such as the Schenkelbacherbäncke and the Pfannenstielerleyen . Kauber Wasser and Wildes Hazard are separated from the Kauber Werth , in the present a tree-lined island. In 19th century plans it is shown as a gravel bank, sometimes under the name Kauber Grund . Down the river, there are shoals that connect Kauber Werth and the rocky island of Falkenau .

In the longitudinal profile of the Rhine, the wild danger, especially at low tide, was a short section with a steep gradient between two sections with a lower incline. When the water level was low, more water flowed off through the Kauber water . A description from around 1850 compares the wild danger with a weir that dammed more water when the water level was low than when the water level was higher. For the ascent was the wild dangerous impassable before removal, for the descent only with sufficient water level, so that shipping mainly to the Kaub water was dependent, where the towpath went. The use of the Kauber water by shipping made it easier to collect the Rhine toll on the Kauber Lände . For this purpose, too, Pfalzgrafenstein Castle was built around 1327 on the Falkenau island off Kaub .

Politically, the left bank of the Rhine belonged to Prussia from 1815 . The right bank of the Rhine was part of the Duchy of Nassau before Nassau was annexed by Prussia in 1866. At present, the wild danger is part of the boundaries of the Rhineland-Palatinate cities of Bacharach ( Mainz-Bingen district ) and Kaub ( Rhein-Lahn district ). The right bank of the Rhine south of the Niedertalbach with Lorchhausen and the Wirbelley belongs to Hesse .

expansion

19th century

Until 1850 hydraulic engineering in the Prussian part of the Rhine was limited to bank protection and the construction and maintenance of the towpaths. In 1851 the Prussian Rheinstrom-Bauverwaltung, which was subordinate to the Upper President of the Rhine Province and operated the systematic regulation of the Rhine. Eduard Adolph Nobiling , who, as the current construction director, was responsible for the Rheinstrom-Bauverwaltung, described the wild danger as a rapids in 1856 and counted it among the sections of the Rhine whose regulation was particularly urgent. The industrialization , the loss of the Rhine customs, old stacking and handling rights and the transition from the towpaths and sail to steam navigation multiplied the volume of goods transported on the Rhine. In 1880 Prussia provided 22 million marks in extraordinary funds for the further expansion of the Rhine over its entire national territory . In the section between Bingen and Sankt Goar , a fairway width of 90 meters was to be created within 18 years . The fairway depth should be two meters at the average, usually lowest water level (corresponding to a water level of 1.50 meters at the Cologne gauge ).

The fairway was determined in such a way that rocks and islands had to be removed as little as possible. This was also justified with the "picturesque appearance" of the Middle Rhine Valley, the great importance of tourism in the 19th century and the "national attraction" that the Rhine allegedly exerts on "every German". The original plans provided for the descent through the wild danger and for the ascent to create two fairways through the Kauber Wasser and the Hahnen . In view of the numerous rocks in the Hahnen , the expansion of this branch of the river was not carried out because of the high costs.

A review of existing maps on a scale of 1: 10,000 carried out around 1849 showed that the information on shoals and rocks there was unreliable. The maps were made on the basis of information provided by the Rhine pilots . A publication based on files of the Prussian Rheinstrom-Bauverwaltung assumes the pilots to have made deliberately inaccurate or false information in order not to reduce their own income opportunities. At the time, the pilots came from some local families; the knowledge of the rocks was often passed on from the pilots to their sons.

Between 1849 and spring 1851 the rocks at Bacharach and Kaub were measured with great effort. For this purpose, a surveying network was determined on both banks of the Rhine by triangulation , which was the basis of the position measurement. The height was measured with dipsticks in a grid of three by three feet . In the narrower area of the wild danger with an area of more than four hectares (over eight Magdeburg acres ), in view of the only slight differences in height there, the bearings were measured in a grid from six to six feet. In addition, the water level was measured at a number of auxiliary gauges at different levels of runoff from the Rhine.

The first rock blasting in the wild danger was carried out between 1839 and 1841. At that time, parts of the road stones were removed. In 1850, several individual rocks were blown up in the fairway near Bacharach, including the altar stones and the scout . Between 1863 and 1866 the fairway in the Wild Hazard was widened by blasting; In addition, other rocks near Bacharach and the Wilder Hazard were removed. Rocks were also removed in the Kauber Wasser before 1898. Several technical innovations made it possible to reduce the initially high costs for rock blasting considerably. During the first blasts, the required boreholes were made from a working raft with hand fiddles. A steam drill was used from 1861. In 1857 the Rheinstrom-Bauverwaltung decided to procure the first diving shaft . The diving shafts were initially used for clearing debris and sharpening rocks that had been left behind during blasting. From 1886 the drill holes were made in diving shafts. In 1894 a so-called rock rammer was procured, a ship that was supposed to smash rocks with a chisel weighing around ten tons . Also came gripping and bucket chain excavators are used.

In 1868 a parallel plant was built to the left of the wild danger between Weinsteinleyen and Weinstein , which was extended to Bacharacher Werth in 1898 . This should prevent water from flowing out of the taps . Between 1868 and 1870, a revetment with trusses and two groynes were built at the lower end of the Hahnen , through which the water level below the Wild Hazard should be raised. Three groynes, which were built between 1898 and 1899 at Kauber Werth , served the same purpose . In order to prevent increased runoff through the side arm, a basic sill was built in 1898 at the entrance to the Hahnen . The reason was regulation work above Bacharach, which should make it easier for shipping to moor in the city. As early as the 1870s, an approximately 1,600-meter-long longitudinal structure was built , which runs from Kohley over the Kauber Werth to the island of Falkenau and separates the Kauber water from the left arm of the river.

The regulation work was completed by 1900. The fairway in the Wilder Hazard was widened to around 70 meters and in the Kauber Wasser to 60 meters. Due to the expansion of the Wild Hazard , the water level had sunk by an average of 17 centimeters. While a more even gradient could be achieved in the Kauber Wasser , this did not succeed in the Wild Hazard: According to measurements from 1929 at a water level of 1.39 meters at the Kaub gauge , the slope in the Wild Hazard was 1: 800, above it was 1: 2100, below 1: 6200, in Kauber Wasser 1: 2430. Raising the water level below the wild danger would have been associated with disadvantages for shipping. A further lowering of the water level above would have required additional rock blasting. Due to the inclination, the descent used the Wilde Hazard , the ascent used the Kauber Wasser . Mountain passenger ships mostly chose the wild danger , as this was the shorter way.

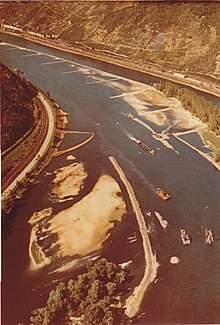

- Recordings of the flight on the Rhine in 1953

20th century

Between 1974 and 1978 the wild danger was expanded to a fairway width of 120 meters; at the same time the way through the Kauber Wasser was abandoned. The construction work was part of the expansion of the Rhine between Sankt Goar and Neuburgweier / Lauterbourg , which has been ongoing since 1964 , with which the navigation channel was to be deepened from 1.70 to 2.10 meters (based on the equivalent water level ). Due to the lower navigation channel depth compared to the lower reaches of the Rhine, the loading capacity of the ships could often not previously be used, so that more ships had to be used with the consequence of congestion in front of bottlenecks like the Binger Loch and the wild danger .

In order to be able to assess the effects of possible construction measures in advance, investigations were carried out at the Federal Institute for Hydraulic Engineering (BAW) using a model , since given the complicated circumstances, only theoretical and computational forecasts were considered insufficient. The 1: 66⅔ scale model encompassed the nearly five-kilometer stretch of river between Lorch and Kaub; measuring devices for recording water levels and speeds were installed on it. In order to be able to record the size and direction of the surface flow in the picture, floating lights and foam polystyrene plates were used. Using a model ship of the Johann-Welker type , possible effects of construction measures on inland navigation were examined. Data on the course and speed of ships in the wild danger were obtained from aerial photographs .

Two expansion variants were examined in the model: an expansion with two separate fairways and an expansion with an undivided fairway. Both variants were found to be feasible; the BAW recommended the variant of an undivided fairway through the wild danger , as this is better suited for push convoys with four barges . A test trip with such a push convoy had shown that the narrowness of the Kauber water caused difficulties. In order to reduce the gradient in the wild danger , bottom depressions were necessary upstream in order to lower the water level there. The filling of excess depths at the level of Pfalzgrafenstein Castle, which was being considered for the same goal, was rejected by the BAW as it could raise flood levels.

In accordance with BAW recommendations, the wild danger was expanded from April 1974. In the course of the construction work, the rock bed was deepened. Five new low-water groynes were built on the longitudinal work between Kauber Werth and the island of Falkenau ; the parallel work north of the Bacharacher Werth was relocated. From the beginning of 1977, a 90 meter wide fairway was available to shipping in the wild danger ; a year later, the widening to 120 meters was almost complete. The construction work resulted in a more even slope in the wild danger . During the entire expansion measure, instead of the originally planned 2.10 meters, only a shipping lane depth of 1.90 meters could be achieved. According to information from 2016, one of six so-called depth bottlenecks, which oppose a fairway depth of 2.10 meters, is at Bacharacher Werth . In the course of the "Unloading optimization Middle Rhine" project, a fairway depth of 2.10 meters is to be created by 2030.

literature

- Karl Felkel: Model studies for the expansion of the Rhine near Kaub. In: Journal for inland navigation and waterways. ISSN 0175-7091 1973 (100), pp. 256-262.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Manfred Halfer: Waterfield names in the Rheinengtal . In: Wilhelm Kimpel: The wonderful Rhine, the great river connecting peoples, a pulsating lifeline of Europe. The helmsmen and pilots on the mountain stretch of the Middle Rhine with their stations in Bingen, Kaub and St. Goar. 2nd edition, Kimpel, Kaub 1999, ISBN 3-929866-04-8 , pp. 235-246, here pp. 236, 239.

- ^ Johann Christian von Stramberg : Rheinischer Antiquarius. Department II, Volume 20, Hergt, Koblenz 1871, p. 35 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ Horst Johannes Tümmers: The Rhine. A European river and its history. 2nd edition, Beck, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-406-44823-2 , p. 342 f.

-

↑ Unger: The regulation of the Rhine between Bingen and St. Goar. In: Journal of Construction . 1897 (47), columns 75-94, here column 76 ( urn : nbn: de: kobv: 109-opus-90337 );

Unger: The regulation of the river Rhine between Bingen and St. Goar. In: Journal of Construction. 1898 (48), columns 629-656, here column 654 ( urn : nbn: de: kobv: 109-opus-90476 );

Felkel, Modelluntersuchungen , p. 256. -

↑ Hartmann: Description of the special recording and bearing of the Rhine river bed in the stretch from Bingen to St. Goar for the removal of the rocks under water in the fairway, which are particularly obstructive for navigation. In: Journal of Construction. 1868 (18), columns 231-252, here column 236 f. ( urn : nbn: de: kobv: 109-opus-87819 );

Wilhelm Meyer , Johannes Stets : The Rhine Valley between Bingen and Bonn. (= Collection of geological guides , volume 89) Borntraeger, Berlin 1996, ISBN 3-443-15069-1 , p. 242. - ↑ Hartmann, recording and bearing , column 237.

-

^ Eduard Nobiling : News about the Rhine stream. In: Journal of Construction. 1856 (6), columns 310-354, here column 323 ( urn : nbn: de: kobv: 109-opus-86963 );

Hartmann, recording and bearing , column 238. - ↑ Eduard Sebald: The Pfalzgrafenstein and the Kauber customs office in the context of the customs and territorial policy of the Pfalzgrafen bei Rhein. In: Castles and Palaces . ISSN 0007-6201 2006 (47), pp. 123-133.

- ^ Nobiling, news about the Rhine river, column 313, 324.

- ^ Robert Jasmund: The work of the Rheinstrom-Bauverwaltung 1851-1900. Memorandum on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Rhine River Management Administration and report on the use of the extraordinary funds approved since 1880 to regulate the Rhine River. Edited from official sources. Book printing of the orphanage, Halle an der Saale approx. 1900, pp. 1–4 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ Jasmund, Work of the Rheinstrom-Bauverwaltung , p. 33.

-

^ Nobiling, news about the Rhine river, column 325;

Hartmann, recording and bearing , column 248. - ↑ Hartmann, recording and bearing , column 232 f.

- ↑ Hartmann, recording and bearing , columns 233-235, 238, 248.

-

↑ Hartmann: The rock blasting in the Rhine river from Bingen to St. Goar. (Part 1) In: Zeitschrift für Bauwesen. 1868 (18), columns 395-408, here column 400 ( urn : nbn: de: kobv: 109-opus-87820 );

Hartmann: The rock blasts in the Rhine river from Bingen to St. Goar. (Part 2) In: Journal of Construction. 1868 (18), columns 547-562, here columns 553, 557 ( urn : nbn: de: kobv: 109-opus-87835 );

Unger 1898, Regulation of the Rhine River , p. 644 f. - ^ Jasmund, Work of the Rheinstrom-Bauverwaltung , pp. 33–49.

-

^ Jasmund, work of the Rheinstrom-Bauverwaltung , p. 64, 70–74;

Felkel, Modelluntersuchungen , p. 256. - ↑ Ministry of Public Works (edit): The further deepening of the Rhine from St. Goar to the mouth of the Main with an average low water = + 1.50 Cölner level. Berlin 1908, p. 22 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ Paul Gelinsky: expansion of the Rhine from Main to the Dutch border. In: Wasser- und Schiffahrtsdirektion Duisburg (Hrsg.): The Rhine. Expansion, traffic, administration. Rhein-Verlagsgesellschaft, Duisburg 1951, pp. 147–206, here p. 154.

- ↑ Jasmund, work of the Rheinstrom-Bauverwaltung , p. 73 f.

- ↑ Unger 1898, Regulirung des Rheinstroms , p. 644.

- ^ Karl Langschied: Hydraulic engineering measures in the mountain range of the Rhine between Bingen and St. Goar. In: Zeitschrift für Binnenschiffahrt und Wasserstraßen 1977 (104), pp. 192–203, here pp. 199 f, 202 f.

- ↑ Felkel, model investigations , p. 258 f.

- ↑ Felkel, Modelluntersuchungen , pp. 259–261.

-

↑ Langschied, Hydraulic Engineering Measures , p. 202 f;

Hydraulic engineering work of the WSD Südwest in 1978. In: Zeitschrift für Binnenschiffahrt und Wasserstraßen 1978 (105), p. 318 f. - ↑ Langschied, Hydraulic Engineering Measures , p. 203.

- ↑ Martin Heying: project of the century on the Rhine. In: Inland Shipping , ISSN 0939-1916 , 10/2016 (71), p. 18 f.

Coordinates: 50 ° 4 ′ 26 ″ N , 7 ° 46 ′ 24 ″ E