Buzz Aldrin

| Buzz Aldrin | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Country: | United States |

| Organization: | NASA |

| selected on | October 17, 1963 (3rd NASA Group) |

| Calls: | 2 space flights |

| Start of the first space flight: |

November 11, 1966 |

| Landing of the last space flight: |

July 24, 1969 |

| Time in space: | 12d 1h 52min |

| EVA inserts: | 4th |

| EVA total duration: | 4h 37min |

| retired on | July 1971 |

| Space flights | |

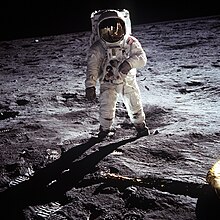

Buzz Aldrin (* 20th January 1930 as Edwin Eugene Aldrin Jr. in Montclair , New Jersey ) is a former American astronaut . Aldrin was the second person to walk on the moon shortly after Neil Armstrong as part of the Apollo 11 mission .

Life

Childhood and youth

Aldrin was the youngest of three children of former Army pilots Edwin Eugene Aldrin Sr. (1896–1974) and Marion Gaddys Aldrin (née Moon, 1903–1968). At the age of two, his father took him with him in a Standard Oil Company aircraft. As a child he was called Buzz . Buzz is the short form of buzzer , the failed attempt to his sister, his brother (Engl. For brother ) to call. In 1988 he officially changed his birth name, Edwin Eugene Aldrin Jr.

During the Second World War his father was drafted as a pilot and only rarely came home for a short time. Aldrin's mother, Marion, suffered from depression and alcohol addiction .

Between the ages of 9 and 15, Aldrin regularly spent his summer vacations at youth camps in Maine . There he enjoyed the camaraderie among the boys and learned to prevail in competitions. During his school days he played football and did pole vaults .

Military service and studies

Aldrin graduated from the Military Academy in West Point , which he in 1951 as the third best in its class with a Bachelor left Accounts as a mechanical engineer. He served in the US Air Force and was used as a fighter pilot in the Korean War, where he flew 66 sorties and shot down two MiG-15s .

After the war, he served in Nevada , Alabama, and Colorado . At the military airfield Bitburg / Germany he served as a pilot in the 22nd Fighter Squadron on an F-100 Super Saber . From 1959 he studied aerospace engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology , graduating in 1963 with a successful doctorate . He wrote his doctoral thesis on "Navigation techniques for manned rendezvous in orbit ". In 1967 he also received an honorary doctorate in natural sciences from Gustavus Adolphus College. After graduation, he returned to the Air Force and served in the Gemini Target Office in Los Angeles and Edwards Air Force Base .

NASA activity

Use in the Gemini program

Aldrin applied to NASA and was introduced to the public on October 18, 1963 as one of 14 astronauts in the third astronaut group. He was the first doctoral astronaut and one of the few who hadn't been a test pilot before.

The mission planning of the Gemini flights was assigned to him as a specialty . For the planned rendezvous of a Gemini spaceship with a target satellite, he was able to apply his knowledge of celestial mechanics by suggesting concentric orbits instead of tangential ones. During the flight of Gemini 5 in August 1965, he served as the liaison officer ( Capcom ) in the control center, but the planned rendezvous could not be carried out due to a defect in the spaceship.

On January 25, 1966, he was assigned as a replacement pilot for Gemini 10 . Usually this led to a nomination for the main crew three flights later, but the Gemini program was to end with Gemini 12 , so that Aldrin would probably no longer be used and had to hope for an early Apollo flight.

Tragically, Aldrin benefited from the deaths of two colleagues. Elliot See and Charles Bassett , who were to be the crew of Gemini 9 , were killed in a plane crash on February 28, 1966. The previous substitute team, consisting of Tom Stafford and Eugene Cernan , moved up, and Aldrin was transferred to the new substitute team of Gemini 9. The flight took place in June 1966, Aldrin was involved again as Capcom. When it turned out that the lining of the nose cone of the ATDA target satellite had not completely loosened due to a few incorrectly mounted safety straps and therefore the planned coupling maneuver with the ATDA was not possible, Aldrin suggested that Cernan should cut the safety straps manually during a space walk. This suggestion, which at the time was extremely adventurous in view of the extremely limited experience with space exits, led NASA officials to some resentment and doubts about Aldrin's suitability for space flight.

Nonetheless, after the Gemini 9 flight ended on June 17, 1966, he was nominated as a Gemini 12 pilot. During the preparation, he was still working as Capcom for the Gemini 10 mission in July 1966.

Aldrin took off on November 11, 1966 with Jim Lovell on his first space flight. His duties included an external mission . This essential part of the Gemini program had not previously worked satisfactorily. However, Aldrin had prepared himself thoroughly and was the first astronaut to simulate weightlessness in a water tank. On three days, Aldrin carried out spacecraft missions in a spacesuit : twice standing in the open hatch, a third time he left the spaceship completely, while still being connected to a line nine meters long. In total, Aldrin spent 5 hours and 30 minutes on the spacecraft, which was a new record at the time.

By moving slowly and carefully, Aldrin was able to carry out all the work without any problems. Regular breaks protected against overheating and fogged visor. Aldrin had thus proven that the last big problem with the Gemini program could be solved.

Use in the Apollo program

At the end of the Gemini program, six teams had already been assigned to the first Apollo flights. Since Aldrin had completed the last Gemini flight, he was not included. Again it was the death of other astronauts that made him move up: In January 1967, the Apollo 1 crew was killed in a ground test. In November, the new plans were published, and Aldrin was on the backup crew of Mission E , which was to test the Apollo spacecraft with the lunar module in a far-earth orbit. At first he was supposed to be the pilot of the lunar module, later - after Michael Collins' sick leave - as the pilot of the Apollo spacecraft . The commander of this substitute team was Neil Armstrong. This flight was classified as Apollo 8 in a modified version (as Mission C '), in which the Apollo spacecraft should fly to the moon without the lunar module.

Since the crew rotation provided that a substitute crew would fly three missions later as the main crew, Aldrin was consequently appointed to the Apollo 11 crew on January 9, 1969, this time as the pilot of the lunar module; the command capsule was to be controlled by Michael Collins, who was airworthy again after a back operation. Assuming that the two outstanding Apollo 9 and Apollo 10 flights were successful, it meant that Aldrin would be involved in the attempt to make the first manned moon landing. In the months that followed, he strongly encouraged his astronaut colleagues and superiors to be the first to step on the lunar floor after landing, until it was finally decided in the course of spring that this privilege would go to the commander, Armstrong. Aldrin was to come in second, which his colleagues (such as Eugene Cernan in his autobiography) apparently saw as a defeat rather than an honor.

Apollo 11 started with the astronauts Armstrong, Aldrin and Collins without any problems on July 16, 1969. On July 21, at 03:15 UTC , Buzz Aldrin was the second person to walk on the moon, almost 20 minutes after Armstrong. In total, Aldrin was outside the lunar module on the lunar surface for 2 hours and 19 minutes. During this time he and Armstrong collected rock samples, took photos and set up research equipment for tests.

Aldrin was in space for a total of 289 hours and 53 minutes, of which 7 hours and 52 minutes were outside his spacecraft.

After returning to Earth, the Apollo astronauts went on strenuous journeys around the world, visiting 23 countries within 45 days.

The picture, which is often found in books about the first moon landing , does not show Neil Armstrong, as is usually assumed, but Buzz Aldrin. Armstrong was commissioned to document the mission with photographs, so there is almost no picture of him on the surface of the moon. Because there is no adequate picture of Armstrong, Aldrin's picture has often been misused.

Life according to NASA

Aldrin left NASA in July 1971 and became director of the ARPS astronaut training center at Edwards Air Force Base, California . After years of working toward a goal as an astronaut, the work struck him as unsatisfactory and he fell into depression, exacerbated by drug and alcohol abuse. In 1972 he left the Air Force and led an unstructured, aimless life for the first time. After some time he went into therapy and became a consultant for an aid organization. He was only able to overcome his alcohol addiction in 1978. Since then, Aldrin has written five books, including an autobiography titled "Return to Earth" because, as he said, the hardest part of his life was not going to the moon but to face what awaited him on his return.

As part of his efforts to popularize space exploration, he was a consultant involved in the production of a computer game and gave it his name, Buzz Aldrin's Race into Space ; it was released in 1992.

Several US patents have been granted to Aldrin . In 1996 he founded his company Starcraft Boosters , which designs cost-effective space systems, and in 1998 the ShareSpace Foundation , a non-profit foundation that aims to promote space tourism. In 2002 he was appointed to a commission that examined the future of the American aerospace industry.

Today he lives in Southern California , gives lectures, appears on television as a space expert and advises companies on film productions. On March 20, 2007, Aldrin officially opened the Skywalk , a glass viewing platform 1200 m above the Grand Canyon in Arizona .

In December 2016, Aldrin was on a trip to the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station in Antarctica . At 86 years old, he now holds the record as the oldest person to have reached the South Pole .

family

Aldrin has been married three times so far. In 1954 he married for the first time; the marriage, which resulted in three children, was divorced in 1972. The second marriage lasted from 1975 to 1978. In 2011, he divorced his third wife, whom he married in 1988.

Freemasonry

Aldrin became a Freemason , like many US astronauts before him, in Montclair Lodge No. 144 in New Jersey. He later affiliated with Clear Lake Lodge No. 1417 in Seabrook , Texas . As a member of the Scottish Rite Valley of Houston , he received the 33rd degree of the Southern Jurisdiction of the Scottish Rite , an administrative degree, in 1969 . July 20, 1969 he deposited as a Special Deputy on behalf of the Grand Master J. Guy Smith of the Grand Lodge of Texas of the Old Free and Accepted Masons a certificate ( Special deputation ) for a first Masonic Jurisdiction on the Moon under a heap of stones. He also took a Supreme Council flag to the moon, which is now on display in the Americanism Museum in Washington, DC . Upon his return, he wrote this down and deposited the record with the Grand Lodge of Texas . He also got involved with the Shriners for free medical care for children.

Honors

In 1969, Aldrin, like the other two Apollo 11 astronauts, was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by US President Richard Nixon , one of the two highest civilian awards in the United States.

In 1969 he was also awarded the Imperial Order of Culture of Japan. In the same year, together with Neil Armstrong and Michael Collins, he received the Worldcon Special Convention Award in the Best Moon Landing Ever category at Worldcon .

In 2000, Aldrin was inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame .

In 2010 he was awarded the Golden Arrow for his life's work.

The lunar crater Aldrin and the asteroid (6470) Aldrin were named after him.

bibliography

- Science fiction novels

-

Encounter with Tiber (1996; with John Barnes )

- German: encounter with the Tiber. Translated by Irene Holicki. Heyne, 1998, ISBN 978-3-453-13850-6 .

-

The Return (2000; with John Barnes)

- German: The return. Translated by Jürgen Langowski. Heyne Science Fiction & Fantasy # 8309, 2002, ISBN 978-3-453-21363-0 .

- Nonfiction and autobiography

-

First on the Moon (1970; with Michael Collins and Neil Armstrong)

- German: We were the first. In collaboration with Gene Farmer and Dora Jane Hamblin. With an epilogue by Arthur C. Clarke . Translated by Heinrich Schiemann . Ullstein, Frankfurt / M., Berlin and Vienna 1970, DNB 455558841 .

- Men from Earth (1991; with Malcolm McConnell)

- Magnificent Desolation: The Long Journey Home from the Moon (2009, with Ken Abraham)

- Mission to Mars: My Vision for Space Exploration (2013, with Leonard David)

- Children's and young people's book

- Reaching for the Moon (2005, illustrated by Wendell Minor)

- Look to the Stars (2009)

- with Marianne J. Dyson: My trip to the moon and back: My Apollo 11 adventure: a pop-up book. Pop-ups: Bruce Foster. Translated by Anke Wellner-Kempf. White Star, Milan 2019, ISBN 978-88-540-4082-3 .

Filmography

- 1973: Return to Earth , together with Wayne Warga

- 1985: A Colt just in case in episode 4x17 "Two stuntmen for space" (High Orbit) as himself

- 1989: Men from Earth , with Malcolm McConnell (story about the Apollo program)

- 1990: Fire, Ice & Dynamite as Himself

- 1994: The Simpsons in episode 5x15 Homer, the space hero (Deep Space Homer) (dubbed role as himself)

- 2006: Numbers - The Logic of Crime in episode 3x11 (short appearance as himself)

- 2007: In the shadow of the moon

- 2010: 30 Rock , episode "Maternal Advice" (guest appearance as himself)

- 2010: Top Gear USA

- 2011: Transformers 3 (brief appearance as himself)

- 2012: Mass Effect 3 speaking role Stargazer

- 2012: The Big Bang Theory in episode 6x5 (short appearance as himself)

literature

- John Clute : Aldrin, Buzz. In: John Clute, Peter Nicholls : The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction . 3rd edition (online edition).

Web links

- Literature by and about Buzz Aldrin in the catalog of the German National Library

- Buzz Aldrin in the German biography

- Buzz Aldrin in the Encyclopedia Astronautica (English)

- Buzz Aldrin in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- Buzz Aldrin on the Internet Speculative Fiction Database (English)

- Buzz Aldrin in the bibliography of German science fiction ( books )

- Literature by and about Buzz Aldrin in the WorldCat bibliographic database

- Works by and about Buzz Aldrin at Open Library

- Official Buzz Aldrin website

- Buzz Aldrin biography . In: NASA website

- The Apollo 11 mission transcript (English)

- Aldrin's dissertation at MIT

Individual evidence

- ↑ http://buzzaldrin.com/faq (English)

- ↑ Andrew Chaikin: A Man on the Moon. Penguin, 2007, p. 585.

- ↑ Buzz Aldrin: Line-of-sight guidance techniques for manned orbital rendezvous (Aldrin's doctoral thesis, 329 pages, 12 MB, PDF, English)

- ↑ Patent US6827313 .

- ↑ Patent US6612522 .

- ↑ Patent US5184789 .

- ↑ Buzz Aldrin still has lung problems . n-tv.de , December 4, 2016.

- ↑ Moon pioneer Buzz Aldrin - divorce at 81 , Spiegel Online from June 17, 2011 (accessed June 17, 2011)

- ↑ Famous Masons II: Dreamers and Doers. (No longer available online.) Grand Lodge of Free & Accepted Masons of the State of New York, archived from the original on August 11, 2012 ; accessed on September 6, 2012 .

- ^ Photo of the flag on display in the Americanism Museum in the House of the Temple in Washington DC

- ↑ Tranquility Lodge No. 2000: History of the Lodge ( Memento from July 26, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) (English)

- ↑ the white lily . 9th year, issue 51/52, June 1970, printing and publishing: Buchdruckerei CW Wenng KG (p. 1682)

- ↑ Grand Lodge of British Columbia and Yukon: Freemasons in Space (English)

- ↑ Phoenixmasonry: Masonic First Day Covers Masonic Ersttagsblätter with Buzz Aldrin (English)

- ↑ Famous Shriners . On the homepage of the Aloha Shriners (Honolulu) (accessed June 9, 2013).

- ↑ Congress of Vienna com.sult 2010 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Aldrin, Buzz |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Aldrin, Edwin Eugene Jr. (maiden name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American astronaut |

| DATE OF BIRTH | January 20, 1930 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Montclair , New Jersey |