Feminist art

Feminist art - English feminist art - describes a contemporary art movement . The term originated in the USA in the late 1960s and was associated with the second women's movement. In feminist art, women artists deal with female identity and the collective experiences of women and deal with conventional gender constructions and art norms.

term

As early as the 19th and early 20th centuries, women artists were articulating feminist themes and demands in their works, including Hannah Höch , Claude Cahun and Alice Lex-Nerlinger . However, the term “feminist art” did not appear in the US until the late 1960s. As early as the early 1970s, the San Francisco Art Institute had a “Feminist Art Program”. In German-speaking countries, Ulrike Rosenbach initially only coined the term “feminist art” for her own work. Besides her, Valie Export was the only one who called herself a “feminist artist” in the 1960s and 1970s. The term spread in German-speaking countries through an essay by Silvia Bovenschen published in 1976 on the question of whether there is a “'female' aesthetic”.

Feminist art is not to be equated with “women's art” or “female art”, not all art by women is feminist. The art historian Margarethe Jochimsen , curator of the exhibition Women Make Art 1976/77 in Bonn, wrote in the exhibition catalog that art by women is feminist, "when women artists show thoughts in the broadest sense that arise from the discriminatory social situation of women, can be derived from the social dictation of so-called female functions, characteristics and behaviors, etc., against which female artists turn in any form ”. According to Jochimsen, feminist art is temporary in character. It only exists as long as social equality between the sexes has not been achieved.

history

The second women's movement developed at the same time as the dawn of art. New art forms such as performance and body art opened up the concept of work to a situation and action-oriented process, dissolved the strict boundaries between art and everyday life and addressed the relationship between artist and life. A new art movement emerged from the interplay with feminism. It included female artists in Europe and the United States who began to struggle against male supremacy in the art world. They founded action groups, demonstrated in front of museums against the exclusion of female artists, organized symposia and curated their exhibitions themselves, founded publishers and magazines and wrote manifestos. In 1972, Valie Export called for Women's Art in her manifesto : “To change the art that man imposes on us means to destroy the facets of the woman that man has built”.

In their works, feminist artists concentrated on topics such as stereotypical images of femininity, physicality, sexuality, sexual violence and questioned power relations and hierarchies. One issue was passivity, which has been associated with the role of housewife and mother for centuries. However, they also contributed fundamentally to the further development of art forms. They used media such as photography, film and video as a means of expression , which seemed to them to be less shaped by the male-dominated art history than painting and sculpture. They created spatial installations with which they occupied and redefined private spaces intended for women, as well as performances and actions for which they made their own bodies the material of their art.

In the 1960s, performance and action art was largely carried out by women. Earlier than it was discussed in Gender Studies , these artists showed that gender is connected to the body and that it is the body that is charged with heteronormative ideas and fantasies. Groundbreaking was the performance Cut Piece by Yoko Ono from 1964, the themes of which Marina Abramovic took up again with similar structures in her performance Rhythm 0 in 1974, and the tap and touch cinema by Valie Export from 1968. They invited people to interact with immovable, passive female bodies and confronted the objectification of women.

The 1970s were the heyday of feminist art in the USA, especially in New York and Los Angeles, in Great Britain and in Germany. In 2007, Jeremy Strick, director of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (MOCA) called the feminist art of those years “the most influential international art movement of the post-war period”. In her time, however, she often found no presence in established art institutions. Judith Bernstein began a series of wall-sized charcoal drawings of hairy round head screws in 1969. With the obvious equation of screws and phallus , she mocked male supremacy. The drawings expressed the anger many women felt. When one of the works in the series, entitled Horizontal, was nominated for the 1974 Women's Work - American Art exhibition at the Philadelphia Civic Center, its director, John Pierron, insisted that the artwork be excluded. It was censored as "morally reprehensible". Thereupon there was a petition from numerous artists, but Pierron left it unmoved. Only on the occasion of a solo exhibition in 2012 at the New Museum of Contemporary Art were the Phallic Screws recognized as “masterpieces of feminist protest”.

Not all artists who dealt with gender roles, images of femininity and gender-specific power relations in their art saw themselves as feminist artists, such as Marina Abramović or Niki de Saint Phalle . At the same time, performances by Abramović from the 1970s, with which she criticized and parodied the traditional role of women in art, and the voluminous Nanas by Niki de Saint Phalle are associated with feminist art.

According to Gabriele Klein , the current situation is characterized by a “ musealization and historicization of the feminist avant-garde ” in art. It is ambivalent if their former social explosive power in the canon of the arts becomes a convention, but at the same time forgotten women artists would be rediscovered. On the other hand, the radical aesthetics of the feminist avant-garde were transferred to the culture industry and processed and marketed as pop in video clips and stage performances by artists such as Madonna , Lady Gaga or Beyoncé, or translated in protest campaigns such as Pussy Riot or Femen .

Feminist artists of the young generation, including Petra Collins and Arvida Byström , use social media channels to stage images of sexuality and aesthetic norms with which they pursue the aim of dealing with them differently. Like the light installations by Jenny Holzer, the art projects in public space in the “Solange” series by Katharina Cibulka are based on text. With 56 square meters of cross-stitch embroidery in pink on dust protection nets, Cibulka draws attention to feminist issues and thus veils buildings that have been male domains for centuries. She covered the scaffolding in front of the facade of the Vienna Art Academy with the slogan "As long as the art market is a boys' club, I will be a feminist", the scaffolding of the Innsbruck Cathedral with "As long as God has a beard, I am a feminist" . The vicar general had asked for the phrase “feminist” and not “feminist” to be used so that it would become clear that he was personally behind it.

Representation in art institutions

Representation of women in the art world has been one of the central themes of feminist artists from the start. In an article by art historian Linda Nochlin entitled Why have there been no great Women Artists? in 1971, which laid the foundation for feminist art studies, she discussed the social and cultural restrictions of women artists and their exclusion from art institutions. Exhibitions curated by feminist artists and art scholars in the 1970s and 80s, as well as publications, aimed to provide evidence that women had worked as artists despite exclusion.

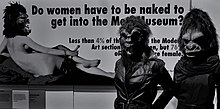

With the rhetorical question “Do women have to be naked to get into the Met. Museum?” On a poster in front of the Museum of Modern Art , the feminist artist group Guerrilla Girls protested in 1989 against sexist discrimination against women in the art world. At the time, women artists in the Modern Art section of the Met Museum made up just five percent and 85 percent of the nudes were female. The campaign drew attention to the fact that women are indeed one of the favorite sources of inspiration and a frequent subject in occidental painting, but that they are rarely present as creators of art. Like the feminist installation artists Barbara Kruger and Jenny Holzer , the guerrilla girls used the visual language of advertising, especially flyposting (wild billboarding) to get their messages across quickly and clearly.

In an article from 2004 Nochlin wrote that women in art are no longer the exception, but a natural part of the art business. According to Gabriele Klein, however, various studies from European and North American countries show that women are by no means equal in the art business and that the image of the “male art genius” still dominates, which is expressed in professional positions, income and reputation. When the Museum of Modern Art dedicated a retrospective to Cindy Sherman in 2012 , the art critic Roberta Smith complained in the New York Times that the museum had missed a great opportunity because it had not honored one of the most important artists of our time in the same area as Willem had before de Kooning , Martin Kippenberger or Richard Serra .

The art institutions that exhibit or collect specifically feminist art include some of the women's museums . The Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art, which opened in the Brooklyn Museum in New York in 2007, has dedicated numerous exhibitions to feminist art from the 1990s to the present day and its influence on international art movements. The Verbund collection in Vienna focuses on the international feminist avant-garde of the 1970s.

Exhibitions

The list includes exhibitions devoted to feminist art or curated to provide representation of art by women.

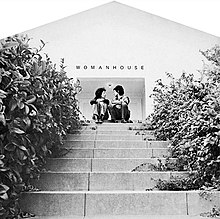

- 1972: Womanhouse was an exhibition project as part of the Feminist Art Program at the California Institute of the Arts , directed by Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro . 21 female students converted an empty two-storey villa in Hollywood (Mariposa Avenue) into an exhibition space, while maintaining the structure of a residential building. With installations and performances, they put housework, the typical interiors and daydreams of women at the center and parodied stereotypes. Womanhouse is considered the first feminist art exhibition.

- 1975: Magna Feminism. Art and creativity in the gallery next to St. Stephan in Vienna. Group exhibition with works by 26 artists and authors based on a multimedia concept by Valie Export. She understood art as a means of expression in the emancipatory process of feminism and brought together evidence of Austrian feminism at the time with works of art in one room.

- 1975: Kvindeudstillingen XX på Charlottenborg (German: Women's Exhibition XX in Charlottenborg) in the Kunsthal Charlottenborg , Copenhagen . International exhibition in the context of the European women's movements, u. a. with the performance Art Must Be Beautiful, Artist Must Be Beautiful by Marina Abramović .

- 1976 / '77: Women make art . Philomene Magers Gallery in Bonn, curated by the art historian Margarethe Jochimsen. The first exhibition on the subject of art and feminism in a commercial gallery in Germany contrasted feminist art with non-feminist art.

- 1977: International women artists 1877–1977 , orangery in Charlottenburg Palace . The exhibition, curated by Sarah Schumann and a women's group at the NGBK in Berlin, presented works by around 190 international female artists, some of whom were barely known in Germany until then, including Frida Kahlo , Eva Hesse , Maria Lassnig , Mary Bauermeister , Ulrike Rosenbach, Diane Arbus , Georgia O'Keeffe , Louise Bourgeois . For the first time, the perspective of women in the performing arts was systematically compiled. The curators wanted to make it clear that women artists were still underrepresented. They met with a lot of resistance because only works by women were shown; their three-year preparatory work remained unpaid. The opening of the exhibition was accompanied by protests.

- 1978: Women's Art , curated by Natalia LL , who is considered a pioneer of feminist art in Poland, in the “Jatki Galeria” in Wrocław . She presented feminist art from western countries, u. a. Carolee Snowman . In 1980 the exhibition took place in Poznań with the participation of Ewa Partum and other Polish representatives of feminist art .

- 1979: The Dinner Party by Judy Chicago. One of the most famous art installations symbolizing the history of women, first exhibited at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art , toured the USA, Canada, Germany, Australia, and Great Britain until 1996 and has been part of the permanent exhibition at Elizabeth A. Sackler since 2007 Center for Feminist Art .

- 1979: Feminist Art Internationaal , Gemeentemuseum Den Haag , was shown in other locations in the Netherlands until 1981 .

- 1980: At the 39th Venice Biennale , two artists, Valie Export and Maria Lassnig, performed in the Austrian pavilion for the first time.

- 1985: Art with a sense of its own - dream or reality? Curated by Silvia Eiblmayr , Valie Export and Cathrin Pichler at Belvedere 21 in Vienna. The exhibition followed up on Magna feminism from 1975 and raised the question of the peculiarities of women's art.

- 2007 to 2009: WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution , curated by Connie Butler for the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles , then at the Contemporary Art Center of the Museum of Modern Art , New York, and in other museums. The exhibition with 120 artists from the USA and Latin America, Europe, Asia, Canada, Australia and New Zealand was the first retrospective to examine and document the connection between art and the feminist movement from the late 1960s to the 1980s.

- 2009–2010: Reflections on the Electric Mirror: New Feminist Video . The exhibition at the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art in the Brooklyn Museum in New York took up the artistic practices of feminist art of the 1970s and presented video art to a new generation of feminist artists on the subject of women.

- Since 2010: Feminist avant-garde of the 1970s from the Verbund collection . The exhibition took place in several places, including a. 2015 in the Kunsthalle Hamburg and 2017 in the Museum of Modern Art Foundation Ludwig Vienna .

- 2013: the subtle difference . The exhibition in the Kunstverein Langenhagen presented feminist artists from four generations, including Valie Export and Franziska Nast .

- 2018: Women House . The exhibition at the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington is a continuation of the Womanhouse project from 1972. 36 international female artists deconstructed stereotypes of domesticity with photographs, videos, sculptures and room-like installations.

- 2020: flower sprinkling . Artists from the Ludwig Collection in the Ludwig Forum for International Art , Aachen, from March 14th to September 13th, 2020.

List of female artists (visual arts)

The following list of women artists is incomplete and contains the names of women who see themselves as feminist artists or whose works or creative phases are counted as feminist art:

- Marina Abramović (born 1946, Serbia)

- Helena Almeida (1934-2018, Portugal)

- Eleanor Antin (born 1935, USA)

- Helène Aylon (born 1931, USA)

- Lynda Benglis (born 1941, USA)

- Judith Bernstein (born 1942, USA)

- Renate Bertlmann (born 1943, Austria)

- Louise Bourgeois (1911-2010, France / USA)

- Teresa Burga (born 1935, Peru)

- Claude Cahun (1894–1954, France)

- Judy Chicago (born 1939, USA)

- Lili Dujourie (born 1941, Belgium)

- Mary Beth Edelson (born 1933, USA)

- Renate Eisenegger (born 1949, Germany)

- Valie Export (born 1940, Austria)

- Tatyana Fazlalizadeh (born 1985, USA)

- Esther Ferrer (born 1937, Spain)

- Guerrilla Girls (in New York City since 1985)

- Theresa Hak Kyung Cha (1951–1982, South Korea / USA)

- Margaret Harrison (born 1940, Great Britain)

- Mary Heilmann (born 1940, USA)

- Lynn Hershman-Leeson (born 1941, USA)

- Jenny Holzer (born 1950, USA)

- annette hollywood (born 1969, Germany)

- Irma Hünerfauth (1907–1998, Germany)

- Alexis Hunter (1948–2014, New Zealand, England)

- Sanja Iveković (born 1949, Croatia)

- Birgit Jürgenssen (1949–2003, Austria)

- Barbara Kruger (born 1945, USA)

- Ketty La Rocca (1938–1976, Italy)

- Leslie Labowitz (born 1946, USA)

- Suzanne Lacy (born 1945, USA)

- Suzy Lake (born 1947, USA)

- Natalia LL (Natalia Lach-Lachowicz, born 1937, Poland)

- Sheila Levrant de Bretteville (born 1940, USA)

- Karin Mack (born 1940, Austria)

- Muda Mathis (born 1959, Switzerland)

- Petra Mattheis (born 1967, Germany)

- Ana Mendieta (1948–1985, Cuba / USA)

- Annette Messager (born 1943, France)

- Rita Myers (born 1947, USA)

- Franziska Nast (born 1982, Germany)

- Alice Neel (1900–1984, USA)

- Shirin Neshat (born 1957, Iran)

- Yoko Ono (born 1933, Japan / USA)

- Orlan (born 1947, France)

- Gina Pane (1939–1990, France)

- Ewa Partum (born 1945, Poland)

- Chris Regn (born 1964, Germany)

- Pipilotti Rist (born 1962, Switzerland)

- Ulrike Rosenbach (born 1943, Germany)

- Martha Rosler (born 1943, USA)

- Ora Ruven (born 1948, Israel)

- Niki de Saint Phalle (1930–2002, France)

- Miriam Schapiro (1923–2015, Canada)

- Carolee Schneemann (1939–2019, USA)

- Sarah Schumann (1933–2019, Germany)

- Cindy Sherman (born 1954, USA)

- Katharina Sieverding (born 1944, Czech Republic / Germany)

- Penny Slinger (born 1947, England)

- Kiki Smith (born 1954, Germany / USA)

- Annegret Soltau (born 1946, Germany)

- Nancy Spero (1926–2009, USA)

- Anita Steckel (1930–2012, USA)

- Agnès Thurnauer (born 1962, France / Switzerland)

- Rosemarie Trockel (born 1952, Germany)

- Lena Vandrey (1941–2018, Germany / France)

- Hannah Wilke (1940–1993, USA)

- Martha Wilson (born 1947, USA)

- Francesca Woodman (1958–1981, USA)

- Nil Yalter (born 1938, Egypt / France)

- Sus Zwick (born 1950, Switzerland)

literature

- Gabriele Schor (ed.): Feminist avant-garde. Art from the 1970s from the Verbund collection, Vienna . Prestel Verlag , Munich 2015, ISBN 978-3-7913-5445-3

- Hilary Robinson (Ed.): Feminism Art Theory. An Anthology 1968-2014 , Wiley-Blackwell, 2015, ISBN 978-1-118-36060-6

- Monika Kaiser: New appointments to the art space. Feminist art exhibitions and their spaces 1972–1987 , Transcript, Bielefeld 2013, ISBN 978-3-8376-2408-3

- Barbara Paul: Feminist Interventions in Art and in the Art Industry , in: Barbara Lange (Hrsg.): History of Fine Art in Germany, Vol. 8: From Expressionism to Today , Prestel 2006, ISBN 978-3-7913-3125-6 , Pp. 480-497

- Patrizia Gozalbez Canto: Feminist art / photography as a subversive tactic , in: Thomas Ernst et al. (Ed.) SUBversions: On the relationship between politics and aesthetics in the present , Transcript Verlag, 2007, ISBN 978-3-8394-0677-9 , p. 221ff.

- Lisa Gabrielle Mark (Ed.): WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution , Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles , publication accompanying the exhibition tour 2007 to 2009, MIT University Press Group, Cambridge / London 2007, ISBN 978-0-914357-99-5

Movie

- “She is the other view” , portrait film by Christiana Perschon about five Austrian female artists of the feminist avant-garde of the 1970s who are now considered established: Renate Bertlmann , Linda Christanell , Iris Dostal , Lore Heuermann , Karin Mack and Margot Pilz . Production: Christiana Perschon 2018 (feature film, color and black / white, 88 minutes).

Web links

- Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum , New York City

- CALL - Platform for Art and Feminism (since 2012)

- The Feminist Art Project

- WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution . Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles 2016 (accessed August 7, 2019)

See also

Individual evidence

- ↑ Silvia Bovenschen: On the question: is there a 'feminine' aesthetic? In: Aesthetics & Communication . Volume 26, 1976, pp. 60-75.

- ↑ Meike Rotermund: Metamorphoses in inner spaces. Video and performance works by the artist Ulrike Rosenbach. Universitäts-Verlag Göttingen 2012, ISBN 978-3-86395-051-4 , p. 441.

- ↑ quoted by Monika Kaiser, ibid. P. 135

- ^ Gabriele Schor: Feminist avant-garde. A radical revaluation of values , In: this. (Ed.): Feminist avant-garde. Art of the 1970s from the Verbund collection, Vienna , Prestel Verlag, Munich 2016, ISBN 978-3-7913-5627-3 , p. 26

- ^ Jeanie Forte: Focus in the Body: Pain, Praxis and Pleasure in Feminist Performance. In: Critical theory and performance. Janelle G. Reinelt, Joseph R. Roach, p. 248 ff , accessed on April 5, 2010 (English).

- ↑ Gabriele Klein : Art Practice of Women: Artistic Practice and Gender-Specific Art Research , in: Beate Kortendiek et al. (Ed.): Handbook Interdisciplinary Gender Research , VS Springer, Wiesbaden 2019, ISBN 978-3-658-12495-3 , p. 1363

- ↑ Peggy Phelan: The Returns of Touchs. Feminist Perfomances, 1960–80 , in: WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution , MIT University Press, 2007, Cambridge / London 2007, ISBN 978-0-914357-99-5 , ISBN p. 350

- ↑ Lara Shalson: Performing Endurance. Art and Politics since 1960 , Cambridge University Press 2018, ISBN 978-1-108-42645-9 , p. 44, p. 27

- ↑ Blake Gopnik: What Is Feminist Art? In: The Washington Post. The Washington Post, April 22, 2007, p. 1,3 , accessed April 5, 2010 (English): "Feminist art of the 1970s was" the most influential international movement of any during the postwar period, "declares Jeremy Strick, director of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles. "

- ^ Roberta Smith: Review: Judith Bernstein Weaves Feminist Messages . In: New York Times. July 31, 2015 , p. 22

- ^ Judith Bernstein HORIZONTAL, 1973 . Image on the website of Art Basel 2015

- ↑ Daniela Hahn: Chronology from 1968 to 1980 , in: Gabriele Schor (Ed.): Feministische Avantgarde. Art from the 1970s from the Verbund collection, Vienna . Prestel Verlag, Munich 2015, ISBN 978-3-7913-5445-3 , p. 477

- ↑ Ken Johnson: Once Banished, Never Silenced. 'Judith Bernstein: HARD' at the New Museum . In: New York Times. December 21, 2012, p. C30

- ↑ Gabriele Klein : Art Practice of Women: Artistic Practice and Gender-Specific Art Research , in: Beate Kortendiek et al. (Ed.): Handbook Interdisciplinary Gender Research , VS Springer, Wiesbaden 2019, ISBN 978-3-658-12495-3 , p. 1363

- ↑ Marina Abramović , in: WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution, Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles , MIT University Press Group, Cambridge / London 2007, ISBN 978-0-914357-99-5 , pp. 209-210

- ↑ Niki de Saint Phalle , in: WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution, Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles , MIT University Press Group, Cambridge / London 2007, ISBN 978-0-914357-99-5 , pp. 292-293

- ↑ Gabriele Klein : Art Practice of Women: Artistic Practice and Gender-Specific Art Research , in: Beate Kortendiek et al. (Ed.): Handbook Interdisciplinary Gender Research , VS Springer, Wiesbaden 2019, ISBN 978-3-658-12495-3 , p. 1365

- ↑ Gabriele Klein : Art Practice of Women: Artistic Practice and Gender-Specific Art Research , in: Beate Kortendiek et al. (Ed.): Handbook Interdisciplinary Gender Research , VS Springer, Wiesbaden 2019, ISBN 978-3-658-12495-3 , p. 1363

- ^ Protesting Art Market 'Boys' Club', Artist Takes Over Vienna's Academy With Feminist Message , Frieze, July 23, 2018

- ^ Carola Padtberg: Feminist slogan veils Innsbruck Cathedral , Spiegel Online, July 27, 2018

- ↑ Korsmeyer, Carolyn: Feminist Aesthetics , The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2012 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.).

- ↑ Angelika Richter: The Law of the Scene , Transcript, Bielefeld 2019, ISBN 978-3-8376-4572-9 , p. 57

- ↑ Elizabeth Manchester: Guerrilla Girls. Do Women Have To Be Naked To Get Into the Met. Museum? 1989 , Tate Modern, December 2004 / February 2005

- ↑ Linda Nochlin: A Life of Learning (PDF; 397 kB) p. 17.2: " Women artists are no longer" exceptions, "brilliant or not, but part of the rule. "

- ↑ Gabriele Klein: Art Practice of Women: Artistic Practice and Gender-Specific Art Research, in: Beate Kortendiek et al. (Ed.): Handbook Interdisciplinary Gender Research, VS Springer, Wiesbaden 2019, ISBN 978-3-658-12495-3 , p. 1364

- ^ Roberta Smith: Photography's Angel Provocateur. 'Cindy Sherman' at Museum of Modern Art , The New York Times, February 23, 2012

- ↑ Monika Kaiser: The Womanhouse 1972 in Hollywood , in: dies., Ibid., P. 30f.

- ↑ Monika Kaiser: Magna Feminismus 1975 , in: dies .: New occupations of the art space , pp. 87-88.

- ↑ Group exhibition: Magna - Feminism: Art and Creativity , Artfacts

- ↑ Monika Kaiser: Kvindeudstillingen XX på Charlottenborg 1975 in Copenhagen, in: dies., Ibid., P. 93ff.

- ^ New Society for Fine Arts, Archive 1977

- ↑ Angelika Richter: The Law of the Scene , Transcript, Bielefeld 2019, ISBN 978-3-8376-4572-9 , Feminist Art Exhibitions in Eastern and Western Europe , p. 56

- ↑ Rosa Schapire Art Prize for Natalia LL from Poland , Süddeutsche Zeitung, October 12, 2018

- ↑ Angelika Richter: The Law of the Scene , Transcript, Bielefeld 2019, ISBN 978-3-8376-4572-9 , p. 57, pp. 68–59

- ↑ Kunstforum International, Volume 79/1985

- ↑ Holland Cotter: Feminist Art Finally takes Center Stage , The New York Times, January 29, 2007

- ↑ WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution , The Museum of Modern Art 2008

- ^ Striking When the Spirit Was Hot . Art Review by Ken Johnson, New York Times, February 15, 2008

- ↑ Carla Acevedo-Yates: Reflections on the Electric Mirror: New Feminist Video , Review in ArtPulse Magazine

- ^ Carsten Probst: Hamburger Kunsthalle. Feminist avant-garde of the 1970s , Deutschlandfunk, March 14, 2015

- ^ Exhibition "Woman": Constrictions and outbreaks , Der Standard, May 12, 2017

- ↑ Feminist Art. Subtle differences , Taz, September 4, 2013

- ^ Exhibition Women House , in: Photography Now

- ^ Alix Strauss: Women, Art and the Houses they build , New York Times, March 12, 2018

- ↑ Exhibition guide : WACK! Art and Feminist Revolution. Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles 4. – 16. July 2007 (English; with list of participating artists; PDF: 989 kB, 9 pages on moca.org ( memento of July 7, 2010 in the Internet Archive )).

- ↑ Gabriele Schor: Feminist Avantgarde: Art of the 1970s from the VERBUND SAMMLUNG. Prestel, Vienna / Munich 2015, ISBN 978-3-7913-5445-3 .

- ^ Article: Opening of "Too Jewish?" Exhibit featuring work of artist Helène Aylon. In: Jewish Women's Archive . March 10, 1996, accessed January 14, 2020.

-

↑ Bernstein, Judith (1942-). In: Jules Heller, Nancy G. Heller (Eds.): North American Women Artists of the Twentieth Century: A Biographical Dictionary. Routledge, London 1997, ISBN 978-0-8153-2584-0 , p. 65.

Roberta Smith: Review: Judith Bernstein Weaves Feminist Messages. In: The New York Times . July 29, 2015, accessed January 14, 2020. - ^ Miguel A. López, Jason Weiss: Teresa Burga: Unfolding the (Social) Female Body. In: Art Journal. Volume 73, No. 2, 2014, pp. 46-65 (English; JSTOR 43189181 ).

- ↑ Portrait: About Mary Beth Edelson. In :! Women Art Revolution: Voices of a Movement. Stanford University, Digital Collections, September 20, 2016, accessed January 14, 2020.

- ↑ Portrait: Mary Beth Edelson. In: moma.org. 2020, accessed on January 14, 2020.

-

↑ Margaret Harrison (1940-). In: visualarts.britishcouncil.org . 2014, accessed on January 14, 2020.

Joanna Gardner-Huggett: The Women Artists' Cooperative Space as a Site for Social Change: Artemisia Gallery, Chicago (1973-1979). In: Social Justice. Volume 34, No. 1, 2007, pp. 28-43, here p. 36 (English; JSTOR 29768420 ). Note: Margaret Harrison is named here as a participant in the 1979 exhibition Both Sides Now at the Artemisia Gallery in Chicago, whose artists are regarded as the “list of canonical feminist artists”.

Dominic Lutyens: Margaret Harrison: a brush with the law. In: The Guardian. April 7, 2011, accessed January 14, 2020. - ↑ Lina Džuverović: Natalia Lach-Lachowicz (Natalia LL). In: tate.org.uk. September 2015, accessed on January 14, 2020.

- ^ Merle Radtke: Rita Myers. Revision of the well-formed man. In: Gabriele Schor: Feminist Avantgarde. Prestel, Munich 2015, ISBN 978-3-7913-5445-3 , pp. 243–246.

- ↑ Sabine B. Vogel: Artist from Iran - Feminism and contemporary Islam: Shirin Neshat. In: faz.net. May 13, 2002, accessed January 14, 2020.

- ↑ Portrait: Miriam Schapiro. In: Jewish Women's Archive . 1998–2020, accessed January 14, 2020.

- ↑ “She is the other view”, Viennale 2019

- ↑ Dominik Kamalzadeh: "She is the other view": Austria's art pioneers in the service of freedom , Der Standard, May 7, 2019