Indefinido and Imperfecto in the Spanish language

The Pretérito indefinido de indicativo and the Pretérito imperfecto de indicativo are (primarily) past tenses in the Spanish language . In terms of their use, however, they show clear differences from the other past tenses ( verb tenses ). Because although the Pretérito indefinido and the Pretérito imperfecto have a similar, perhaps even identical temporal structure, their mutual (secondary) difference is determined by their respective aspect values.

Strictly speaking , the Spanish indefinido and imperfecto do not express different "time levels", but different perspectives on an action in the past, so that they should actually be called an aspect and not a tense. A grammatical ( morphological ) contrast between the imperfect and the perfective aspect cannot be found in German. For this reason, for a deeper understanding, the following representations of the terms “ tense ”, tiempo , “ aspect ”, aspecto gramatical and “ action type ”, modo de acción have been sent first .

Explanation

Such an aspect opposition or Romance, aspect opposition is represented by two differently conjugated tenses. In its linguistic rendering, it enters into an internal, rather subjective perspective of the storylines to be described. These two tenses, pretérito indefinido and imperfecto , are not about differences in temporality, but about different aspects. The perfective aspect captures the verbal action as a completely completed process with a definable duration (point in time). This also applies to the pretérito perfecto compuesto , which in this respect is similar to the pretérito indefinido or pretérito perfecto simple and expresses the aspect of the "completion or completion" of an action. With the pretérito perfecto compuesto , however, there is a proximity to the present, with the pretérito indefinido or pretérito perfecto simple there is a distance to the actions or events.

The imperfective aspect , on the other hand, puts the development of the verbal action in the foreground, without indicating the conclusion of the same (period).

If you use the grammatical term “tense”, only the grammatical, i.e. verbal, verbal category is meant. In the Spanish grammar there are two morphologically different, oppositional tense systems and thus also aspect systems, namely the perfect-past tense system (tense-aspect-mode marking). The aspect provides information about whether a situation is perceived by the speaker as ended or not ended. Here, the verbs for the perfect, closed situation are to be contrasted with the imperfective verb forms for the situation that has no end point. In the Romance languages, the aspect helps to express the aspectuality through grammatical and morphological means. In Romania, the aspect is anchored in the tenses, which distinguishes it from the Slavic languages. Aspectuality, on the other hand, is a higher-level grammatical- semantic category that functions as a linguistic universal .

The aspect must be clearly distinguished from the type of action . While the aspect is a morphological-grammatical phenomenon, the type of action depicts a lexical-semantic phenomenon. The grammatical aspect refers to the morphological marking of the tenses for the Pretérito indefinido and Pretérito imperfecto . However, the focus is not on the "time levels", i.e. the tenses, but the temporal structure of actions, the "time direction reference". For the aspect, it is decisive what extent an action has, whether it is completed or is still ongoing and how the speaker is integrated into this situation.

If one describes the course of action in the sense of a continuous sequence in the storyline, hilo argumentally - the question of the time limitation of a (time-bound) situation arises - then the past events are depicted in the imperfect tense and thus also the aspect system. So actions in the course - even if these occur as parallel events; to a certain extent they form the framework for newly occurring events. - Examples estaba , perfective- llegó :

Estaba haciendo un ejercicio yoga. – „Sie/er war gerade dabei, eine Yogaübung zu machen.“ Imperfektiv: estaba Estaba haciendo yoga, cuando llegó el agente comercial. „Sie/er machte gerade wie immer Yoga, als der Handelsvertreter kam.“

Perfect: hizo - example:

Hizo un saludo al sol. – „Sie/er machte einen Sonnengruß.“

However, if a report is made about a process in the past that presents itself as a point, as a delineated entity taking into account a beginning and an end, as it were as a "time capsule", only the perfect tense and thus aspect system is available for linguistic mapping Available.

- Pretérito perfecto compuesto : ¿Qué ha sucedido recientemente? - “ What happened recently? "

- Pretérito indefinido : ¿Qué pasó? - “ What happened? What happened next? "

- Pretérito imperfecto : ¿Cómo era? - " How was it? What was it? "

- Examples:

Mi hermano ha muerto por un ataque de apoplejía. Lo recuerdo aún mucho. Pretérito perfecto compuesto – Nähe zur Gegenwart Mi hermano murió hace tres años. Pretérito indefinido – Distanz zum Ereignis Nuestros antepasados también morían por arterias obstruidas. Pretérito imperfecto – Erzählhintergrund

In the Pretérito indefinido the boundaries, contours or edges of the verbal events are drawn into the area of mental attention, while in the Pretérito imperfecto the temporal boundaries are pushed into the background (compare figure-ground perception ) or faded out. In the case of verbal events that are presented in the imperfecto, the (temporal) beginning and end remain indefinite, it is not even said that they took place at all.

Pretérito indefinido: ¿Cuándo fue la última vez que llovió? – „Wann (genau) war das letzte Mal, dass es regnete?“

If actions or events taking place simultaneously are described in one sentence, they are in the Pretérito imperfecto . - example:

Mientras cenábamos veíamos la televisión. – „Während wir noch zu Abend aßen, sahen wir noch Fernsehen.“

If successive actions or events are reported, they appear like a "closed time bubble" in the Pretérito indefinido . - example:

Llegó a trabajo, se cambió, bebió un café y se fue al ordenador. – „Er/sie kam schon zur Arbeit, wechselte die Kleidung, trank einen Kaffee und war schon am Computer.“

If two strands of action are combined in a sentence, or if they overlap, the interrupting action appears in the pretérito indefinido , while the interrupted happening or event appears in the pretérito imperfecto . - Examples:

Estábamos escuchando la radio cuando oyó un ruido. – „Wir hörten gerade Radio, als er/sie schon Lärm hörte.“ Pretérito imperfecto de indicativo + Pretérito indefinido de indicativo Si. Pensé que lo pensabas. – „Ja, ich dachte, dass du es dachtest.“ Pretérito indefinido de indicativo + Pretérito imperfecto de indicativo

Interplay of tense, aspect, type of action, mode and modality

For Ulrich Sacker (1983), the tense, the aspect and the types of action are to be viewed as correlative categories that are closely interrelated so that an interaction between the categories of tense, mode and aspect develops on the grammatical level.

Tense

The tense , tiempo gramatical is a grammatical category that expresses the temporal relationship, the external time between two events or facts (time stages). The tense always refers to the time of a certain context . This context, which becomes the point of reference for actions and events in the grammatical category of the tense, can in a sense be seen as its starting point and is mostly to be equated with the time of speaking.

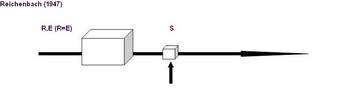

The grammatical category of "tense" results in a structuring that is not directly related to (physical) time , but must always be related to the speaking time S (event time E - speaking time S - reference time R ) and relations to expression can bring (prematurity - simultaneity - laterality). In the sense of Hans Reichenbach's terminology, different times have been distinguished for the semantic determination of the tenses.

According to Horst G. Klein (1969) the tense is deictic- relational, i. H. it refers to a period of time relative to the contextual opening time S is given. While tenses show events E in the past, present and future depending on the speaking time S , aspect and type of action are viewed as non- deictic time categories.

aspect

Karl Brugmann (1887), a student of Georg Curtius at the University of Leipzig, studied the Indo-European verbal system. Together with Berthold Delbrück , he developed Curtius' approach further, as he was of the opinion that the concept of “type of time” was too vaguely delimited from “time level”. It was also Brugmann who included the term “action” in the scientific discussion; he saw in the "action" expressed more the way in which the action of a verb takes place in contrast to the "time stage".

The aspect , aspecto gramatical , is a grammatical category that expresses the internal time of an event or a state (see also the history of the term "aspect" ). According to its polarity, this category denotes a beginning, a repetition, a course, a duration and an end of the action or the event. Of the Germanic languages , it is only the English language that is able to express the aspect with grammatical means; by means of its progressive form . Only in some German dialects is there a progressive form (Rhenish form or " am-progressive ").

The aspect is bipartite or also called binary in Spanish. It describes the inner temporal contouring of an action, an event from the speaker's perspective. So the aspect stands for the setting or the removal of all possible limits in the predicate . The consequences of being limited or unlimited are that an action that is alienated in the perfective is presented as a whole with a starting point, but above all with an end point. In other words, the actions, events or facts, must reach their end point. The perfective is often related to the tense, the external time of past tenses. In certain past tenses it can be stated whether an action has taken place and whether it no longer takes place. The imperfect, on the other hand, abolishes all possible limits. Another way to give language to infinity, to depict the limitlessness of an event, is that it is expressed through constant repetition (iterativity). In other words, all forms of alienation through language that have inherent limits will no longer be able to show them in the imperfect. As a verbal category, the aspect provides information on whether an action, fact or event can be characterized by a degree of isolation, the perfect aspect, or by a non-isolation, the imperfective aspect. While the aspect is a morphological - grammatical phenomenon, the type of action depicts a lexical - semantic phenomenon. According to Bernd Kortmann (1991), types of action, in contrast to the aspect, are not grammatical categories, but refer to the inherent temporal properties of predicates , and are therefore linked to the lexicon . The aspect does not consider the "time level reference" or the time levels, but the temporal structure of actions or "facts". What is decisive is the extent of an action or fact, whether it is completed or is still ongoing, and how the speaker is involved or integrated into these processes.

The perfection as an aspect form is u. a. expressed by the Pretérito indefinido and can also be expressed with atelic verbs, verbo atélico (type of action ):

Ayer comí pollo. Gestern aß ich Hühnchen.

as well as with telic verbs, verbo télico :

Ayer fui a Barcelona. Gestern fuhr ich nach Barcelona.

The imperfectivity as an aspect form, which u. a. expresses with the past tense of the Pretérito imperfecto , can also be connected with different predicates:

Ayer a las ocho de la mañana granizó. Gestern um acht Uhr in der Früh hagelte es. En ese momento salí de mi coche. In diesem Moment stieg ich aus meinem Auto.

Promotion type

The type of action , clase de acción o modo de acción, captures the fact that every action, event and state can have a beginning, an end and an intermediate phase. Types of action express in a lexical way how the event inherent in the verb is expressed, how it "runs off" or how the meaning of the beginning, the limitation, the iterativity is shown in its intrinsic temporal determination. The types of action are used to map lexical-semantic phenomena, thus showing the (internal) course, the extent and the result of a process. The type of action of a verb is indicated by means of a special form of time reference. Different verbs can have an inherent temporal characteristic. Through this action it is conveyed whether an action is beginning, is ongoing or is finished. The types of action thus describe the gradations and the course of the events, actions or facts identified by the verb. The action can be differentiated according to its content (cause, intensity, repetition, reduction in size) and its course over time (process, completion, beginning, transition, end).

In German, for example, the types of action are characterized by lexical semantics on the verb. For this purpose, the affixes , more precisely prefixes, are in the foreground, for example for the verb "bloom", which characterizes the duration of the action; or “bloom”, which marks the beginning and “wither” that characterizes the end of the “blooming process”.

The type of action therefore describes the internal temporal structure of situations and thus the objective relationships of the event with regard to its temporal course, for example as extended or not extended in time, as goal-oriented or non-goal-oriented, etc. These facts can be described with the terms ingressive , ingresivo , inchoative aspect , incoativo , Durativ , durativo , Iterative , iterativo , Frequentative , frecuentativo , tripod , Momentativ , egressive , egresivo and conative describe.

Concerning the terminology and the classification of Zeno Vendler (1957/1967) in four basic types of action, it can be concluded that only telic verbs can occur in the perfect and imperfective aspect, or, to put it another way, only with telic verbs can the speaker choose between the aspects. In contrast to the type of action, however, the aspect describes the subjective way of looking at the event according to the basic categories perfective (event thought to be closed) and imperfective (event thought not to be closed). There are also more complex aspects, such as the perfect aspect, which describes a state resulting from a completed event. Instead of the term of the perfective verb, Ulrich Engel (2004) uses the terms of the "telic verb", verbo télico, and the term of the "atelic verb", verbo atélico, for that of the imperfective verb . Regarding the perfection of Spanish verbs, this is u. a. expressed through the pretérito indefinido and can be combined with atelic, verbos atélicos o permanentes or with telic verbs, verbos télicos o desinentes .

Ayer comí sopa de pescado. Gestern aß ich Fischsuppe. atelisches Verb, verbo atélico. Verben die Ereignisse ohne Endpunkt bezeichnen Ayer fui a Barcelona. Gestern fuhr ich nach Barcelona. telisches Verb, verbo télico. Verben die Ereignisse mit natürlichem Endpunkt bezeichnen

The verbal system of the Romance languages is not as evenly developed in terms of telicity, telicidad morphologically as, for example, in the Slavic languages . For Spanish, this can only be definitely determined if the pronoun "se" is present. - Examples:

leer un rato – leerse una gaceta eine Weile lesen (atélico) – lesen eine Zeitung (télico) comer pollo – comerse un pollo essen Hühnchen (atélico)- essen ein Hühnchen (télico) beber vino – beberse una copa de vino trinken Wein (atélico) – trinken ein Glas Wein (télico)

Nevertheless, at the lexical level there is a differentiation between aspect or type of action or a unique, semi-active circumstance of action and a completed action, resulting in a clearly defined beginning and end. Both can be z. B. using the German verb pairs such as “erblicken” and “haben”, “find” and “seek”, “hear” and “listen”; in each of these pairs the first verb has a meaning similar to the perfect verbal aspect or aorist: it marks a unique, completed action, with a clearly defined beginning and end. The second verb, on the other hand, indicates an ongoing process that cannot be restricted to a specific moment or a specific action; Repeated or familiar actions can also be displayed in this way.

Spanish expresses the type of action, how an event or action takes place, also with verbal paraphrases through the perífrasis verbales . This is understood to be verbal groups that are constituted as verbal periphrases from a combination of a finite verb and one (or more) infinitive verb forms of Spanish , whereby the finite verb has largely lost its own meaning, but to modify or characterize the verbal occurrence, especially with regard to the type of action further has the effect that the verb refers in the infinitive. These are constructions with verbs of movement that are connected to the infinitive, gerund or participle and lose their original meaning. They take on the functions of a pseudo auxiliary verb . The periphrastic constructions denote: beginning, repetition, duration, end of the action.

mode

The mode , modo gramatical is the linguistic expression of modality that has to do with the subjective attitude of a speaker for the event. Modality can be understood as a semantic category, it allows a speaker to express the way of the existence of events and situations (indeterminacies) to which these statements refer. This allows the speaker to make a statement as to whether a certain situation is "possible", "necessary" or "impossible". While the mode is a grammatical-morphological category or concept that expresses the speaker's assessment of reality or the possibilities for realizing the verbalized facts, the modality, on the other hand, is understood as a functional-semantic category or concept. Nevertheless, modality can also be expressed through grammatical-morphological means of the modes (e.g. the indicative , subjunctive , imperative ). Since the modes are part of the modality from this point of view, modality can be understood as an umbrella term.

The recording of time or the verbalization of temporal experiences is grammaticalized differently in the different languages. It appears as a tense and is a grammatical category which - relative to an actual or assumed speaking time S - indicates the temporal position of the situation that is denoted by the verbalized sentence .

Pretérito indefinido or Pretérito perfecto simple

The Pretérito indefinido de indicativo is used when the action in the past is completed. The Pretérito indefinido identifies an event or fact that has been completed and defined in the past; also new actions or events. It describes a (long) past, (far) distant event or refers to a time in the past; in other words, to events that took place at or from a certain point in time in the past. This implies the idea of punctuality and uniqueness but also that of the textual chains of action. The indefinido is suitable for describing successive action sequences, on the other hand - in comparison to the imperfecto - it is not suitable for promising unfinished and lasting states. In this it resembles a property of the German simple past . Aspectively, a completed action is expressed that took place in a completed period of time. In Hans Reichenbach's terminology , the following structure would be given: E. R - H, event time. Reference point - talk time. - example:

Nadie se lo dijo. – „Niemand ihr/ihm es schon sagte.“

If the speaker chooses the Pretérito indefinido as a reference for describing an action or event in the past, he defines the occurrence or event as from a point in time and implies that there are hardly any possibilities of influencing it. It is the time used for narrations, reports and portrayals. It is a simple time and mostly refers to definite times in the past.

The following words refer to these current events: ayer , anteayer , el año pasado , anoche , la semana pasada , el martes pasado , de repente , de… a , desde… hasta , después , el martes de la semana pasada , en… , de pronto , hace tres días .

- Ask about the indefinido : ¿Qué pasó? - “ What happened then? "

- Ask about the imperfecto : ¿Cómo era? - “ What was it? "

Some verbs have a different German translation , depending on whether they are in the imperfecto or indefinido . Thus conocer know in Imperfecto to le conocia I knew him (over a longer period) , while le Conoci unique to the last action I have come to know him is.

Formation of the Pretérito indefinido or Pretérito perfecto simple

The regular verbs that end in –er or –ir have the same forms. The endings of the first person plural (nosotros) are identical to the conjugation forms in the present tense.

| person | Endings habl-ar | Endings tem-er | Endings part-ir |

|---|---|---|---|

| yo | -é | -í | -í |

| do | -aste | -ist | -ist |

| usted, él, ella | -O | -ió | -ió |

| nosotros / -as | -amos | -imos | -imos |

| vosotros / -as | -asteis | -isteis | -isteis |

| ustedes, ellos, ellas | -aron | -ieron | -ieron |

In the case of irregular verbs , the term word stem , stem or here verb stem plays an important role; in linguistic morphology it generally refers to a component of a word that serves as a starting point for morphological operations such as word formation or, here, specifically inflection . It is therefore a potentially incomplete structure that can appear as a counterpart to an affix .

Two important differences can be observed in the Pretérito indefinido. On the one hand, there are verbs, as in the conjugation of the present tense, in which the accented vowel changes in the stem. Example sentir with the vowel change or ablaut e to i in the third person singular and plural.

| person | Endings serv-ir |

|---|---|

| yo | serví |

| do | serviste |

| usted, él, ella | s i rvió |

| nosotros / -as | servimos |

| vosotros / -as | servisteis |

| ustedes, ellos, ellas | s i rvieron |

On the other hand, there are also complete changes to the respective verb stem. Here are some examples of irregular changes in the verb stem. Thus, although still of a certain regularity, the suffixes of the indefinitive conjugation show to a certain extent "mixed" forms.

| Verbs | Stem | Endings, general | |

|---|---|---|---|

| andar | anduv- | -e, - i ste, -o, - i mos, - i steis, i eron | u trunk change |

| caber | cup | -e, -iste, -o, -imos, -isteis, -ieron | u trunk change |

| decir | dij- | -e, -iste, -o, -imos, -isteis, -eron | j-stem change |

| estar | estuv- | -e, -iste, -o, -imos, -isteis, -ieron | u trunk change |

| haber | hub | -e, -iste, -o, -imos, -isteis, -ieron | u trunk change |

| hacer | hic- | -e, -iste, -o, -imos, -isteis, -ieron | i-stem change |

| poder | pud- | -e, -iste, -o, -imos, -isteis, -ieron | u trunk change |

| poner | pus- | -e, -iste, -o, -imos, -isteis, -ieron | u trunk change |

| querer | quis- | -e, -iste, -o, -imos, -isteis, -ieron | i-stem change |

| drool | sup- | -e, -iste -o, -imos, -isteis, -ieron | u trunk change |

| tener | tuv- | -e, -iste -o, -imos, -isteis, -ieron | u trunk change |

| traer | traj- | -e, -iste -o, -imos, -isteis, -eron | j-stem change |

| venir | vin- | -e, -iste -o, -imos, -isteis, -ieron | i-stem change |

| Verbs | Stem | Endings, general | |

|---|---|---|---|

| abrir | abr- | -í, -iste, -ió, -imos, -isteis, -ieron | |

| caer | ca- | -í, -iste, -yó, -imos, -isteis, -yeron | 3rd person Sing./Plur. i to y |

| coger | cog- | -í, -iste, -ió, -imos, -isteis, -ieron | |

| comer | com | -í, -iste, -ió, -imos, -isteis, -ieron | |

| conocer | cono- | -í, -iste, -ió, -imos, -isteis, -ieron | |

| represent | di- | -i, -iste -io, -imos, -isteis, -ieron | no acento agudo |

| deber | deb- | -í, -iste, -ió, -imos, -isteis, -ieron | |

| dormir | dorm- | -í, -iste, -ió, -imos, -isteis, -ieron | 3rd person Sing./Plur. o to u |

| escribir | escrib- | -í, -iste, -ió, -imos, -isteis, -ieron | |

| ir | fu- | -i, -iste, -e, -imos, -isteis, -eron | no acento agudo |

| empty | le- | -í, -iste, -yó, -imos, -isteis, -yeron | 3rd person Sing./Plur. i to y |

| oir | O- | -í, -iste, -ió, -imos, -isteis, -ieron | |

| oler | oil- | -í, -iste, -ió, -imos, -isteis, -ieron | |

| sentir | sen- | -í, -iste, -ió, -imos, -isteis, -ieron | |

| ser | fu- | -i, -iste -io, -imos, -isteis, -ieron | no acento agudo |

| vivir | vi | -í, -iste, -ió, -imos, -isteis, -ieron |

| Verbs | Stem | Endings, general |

|---|---|---|

| amar | at the- | -é, -aste, -ó, -amos, -asteis, -aron |

| cantar | cant- | -é, -aste, -ó, -amos, -asteis, -aron |

| gustar | gust- | -é, -aste, -ó, -amos, -asteis, -aron |

| hablar | habl- | -é, -aste, -ó, -amos, -asteis, -aron |

| llevar | llev- | -é, -aste, -ó, -amos, -asteis, -aron |

| pension | pens | -é, -aste, -ó, -amos, -asteis, -aron |

Verbs that end with the suffixes -car , -gar , or -zar become irregular in their first person singular for reasons of pronunciation. Some verbs show a change in the spelling for certain conjugation forms so a possible i between two vowels becomes y . Examples: caer fallen caí, caíste, ca y ó, caímos, caísteis, ca y eron , creer believe , creí, creíste, cre y ó, creímos, creísteis, cre y eron .

But consonants are also changed, so a z before e becomes c . Example: cruzar cross , cru c é, cruzaste, cruzó, cruzamos, cruzasteis, cruzaron . A consonant g before the vowels e or i a gu . Example play jugar , ju gu é, jugaste, jugó, jugamos, jugasteis, jugaron .

In the verbs that end in -ucir , uc becomes the vowel-consonant connection uj , the other endings of these verbs are altogether irregular. Example trad uc ir translate trad uj e, trad uj iste, trad uj o, trad uj imos, trad uj isteis, trad uj eron

Pretérito imperfecto

In the Pretérito imperfecto de indicativo - as in the French Imparfait and the English Past Progressive - there are long-lasting or repetitive actions in the past that were not completed in the past or the end of which remained indefinite in the past, e.g. había una vez .. .. once upon a time . Because repetitive actions are understood as unfinished and unrestricted events. The process, the action ran parallel to the reference point of the spoken word in the past. It is a parallelism in the extended sense of a simultaneity meaning with which the verbalized process can be before or after the reference point.

It's a simple time, so it's one of the formas simple . The imperfecto is always used when recounting events that have taken place over and over again in the past. One emphasizes here the repetition (iterative type of action, verbos iterativos ) and regularity (durative type of action, verbos durativos ). The narrator wants to describe an action or event that lies in the past from the present, the point of observation or focus. He does this at a time when the action was taking place, i.e. it was not yet complete. It is therefore not known to the viewer of the action whether the events that began in the past are still ongoing. So the event was “not perfect”, thus “imperfect”. In Hans Reichenbach's terminology , the following structure would be given: E. R - H , event time. Reference point - talk time.

Los novios se escribían cada semana. Das Paar schrieb sich einander jede Woche.

Therefore, this tense is used for simultaneous events in the past or when the ongoing events in the past are interrupted by a new action. The Pretérito imperfecto can also be used to describe situations, people, landscapes, weather or the like in the past . The imperfecto is used to describe repetitive actions, the enumeration of events or states in the past that lasted longer or existed simultaneously. If a scene, a framework plot , is described, the imperfecto is used and thus enables the speaker to provide more detailed explanations and explanations.

The following words lead to this time: antes , a menudo , entonces , en aquel tiempo , con frecuencia , de vez en cuando , mientras , cada día , cada semana , cada vez que , siempre , porque , de joven , normalmente , generalmente , en esa época , poco a poco , todas las mañanas . They form the background, so to speak, while the foreground is described in indefinido . The following words indicate such simultaneous use of both tenses: una vez , de repente , enseguida . - Examples:

* Cuando era joven, monté a caballo una vez.– „Als ich jung war, bin ich einmal geritten.“ * Era un rey permanentemente. – „Er war König dauerhaft.“

indicates a durative type of action during the sentence

* Era un rey repetidamente. – „Er war König immer wieder.“

specifies the iterative type of action of the past tense. Past actions or facts are considered in their course and verbalized, their completion or their result are of no interest.

* Salía, cuando tú entrabas.

Overall, the pretérito imperfecto describes an event or an action that happened in the past procedurally, detached from time and course. It describes permanent, constant actions, facts or a constant process in a past time, whereby the decisive factor is not the duration of this process, but its non-localizability on the time axis.

* Ese lago estaba situado al derecho del camino.

Formation of the pretérito imperfecto

| person | Endings habl-ar | Endings tem-er | Endings part-ir |

|---|---|---|---|

| yo | -aba | -ía | -ía |

| do | -abas | -ías | -ías |

| usted, él, ella | -aba | -ía | -ía |

| nosotros / -as | -abamos | -íamos | -íamos |

| vosotros / -as | -abais | -íais | -íais |

| ustedes, ellos, ellas | -aban | -ían | -ían |

There are three irregular verbs in the Spanish Pretérito imperfecto .

| Verbs | Stem | Endings, general | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ir | i- | -ba, -bas, -ba, -bamos, -bais, -ban | i in the 1st person plur. with Acento agudo |

| ser | he- | -a, -as, -a, -amos, -ais, -an | e in the 1st person plur. with Acento agudo |

| ver | ve- | -ía, -ías, -ía, -íamos, -íais, -ían | first i always use acento agudo |

Use of the Pretérito indefinido and Pretérito imperfecto in Spanish

According to Siever & Wehberg (2016) the use of the imperfect and the indefinid depends on:

- Narrative perspective ;

- Text structure ;

- Context and partially from the

- Speaker intention.

Since the Pretérito imperfecto serves to describe scenes on which, as a background, as it were, a new action develops or an already ongoing action is interfered with by a new event or action, all incidental circumstances and all further descriptions or all other objects that the narrator wishes to move into the (descriptive) background, to be placed in the Pretérito imperfecto , but also in the Pretérito pluscuamperfecto . The pretérito indefinido and the pretérito anterior serve to express the (narrative) foreground, i.e. for the new event or the new action .

The pretérito indefinido is used when the action is completed in the past, acción completada . It describes a (long) past, (far) distant event or refers to a past, known point in time, or better period of time, i.e. to events that took place at or from a certain point in time in the past over a certain period and it describes its duration entirety , evaluación globally . It can be symbolized well with a " time capsule ", cápsula del tiempo .

Aspectively, a completed action is expressed that took place in a completed period of time. Linked to this is its use to describe a completed action in its entirety, as an overall impression, assessment or presentation . - Examples:

El torneo de voley estaba bien. „Das Volleyballturnier war gut.“ Imperfecto, Teilbewertung, -schau, evaluación parcial, unabgeschlossen, Bewertung aus damaliger Sicht, im Sinne, das einige Spielsequenzen gut waren. El torneo de voley estuvo bien. „Das [gesamte] Volleyballturnier war gut.“ Indefinido, Gesamtbewertung, -schau, evaluación global, abgeschlossen, das gesamte Turnier wird bewertet.

In Hans Reichenbach's terminology, the following structure would be given: E. R - H, event time. Reference point - talk time. If the speaker chooses the Pretérito indefinido as a reference for describing an action or event in the past, he defines the occurrence or event as from a point in time and implies that there are hardly any possibilities of influencing it. It is the time used for narrations , reports and portrayals. It is a simple time and mostly refers to definite times in the past. - Examples: Pretérito indefinido :

Cuando vino mi hermano trajo obsequios. – „Als mein Bruder kam, brachte er kleine Aufmerksamkeiten mit.“ Cuando fui de trabajo comí algo. – „Als ich zur Arbeit ging, aß ich ein wenig.“ Tuvieron una casa. „Sie bekamen ein Haus.“ Conocí a Denis Diderot. – „Ich lernte Denis Diderot kennen.“ Conocí a Denis en la coterie holbachique. – Ich lernte kennen Denis in der Coterie holbachique. Das Kennenlernen ist zum Sprechzeit S, Origio in der Vergangenheit abgeschlossen.

But Pretérito imperfecto :

Le conocía bien. – Ihn ich kannte gut. Cuando llegué a la coterie holbachique no conocía a nadie. – „Als ich kam zur Coterie holbachique nicht ich kannte niemanden.“ Der Tatbestand, dass ihn niemand im Salon von Paul Henri Thiry d’Holbach kannte, dauerte zum Sprechzeitpunkt S an. Estaba ante la puerta de la cárcel de Santa Águeda y era libre. – „Ich stand vor dem Tor des Gefängnis Santa Agueda und war frei.“ Der Tatbestand, dass er/sie vor dem Tor stand, dauerte zum Sprechzeitpunkt S an; aber sein „freigesetzt-sein“ war abgeschlossen.

The following words refer to this (continued) current affairs: ayer , anteayer , el año pasado , anoche , la semana pasada , el martes pasado , de repente , de… a , desde… hasta , después , el martes de la semana pasada , en … , De pronto , hace tres días .

- Ask about the indefinido : ¿Qué pasó? - “ What happened then? "

- Ask about the imperfecto : ¿Cómo era? - “ What was it? "

- Some verbs have a different German translation depending on whether they are in the imperfecto or indefinido .

So conocer (get to know) in the Imperfecto le conocía becomes I knew him (over a longer period of time) , while le conocí is about the last one-off action I got to know him .

| Verbs infinitive | German translation | Pretérito imperfecto (course of action) | German transmission | Pretérito indefinido (entry of the action) | German transmission |

| tener | to have | tenía | I had (as always) | do it | I got (instantly, at the moment) |

| drool | knowledge | sabía | I already knew | great | I found out (suddenly) |

| conocer | know | conocía | I already knew | conocí | I got to know (instantly) |

| ir | go | iba | I was out and about as always, I went as usual | fui | I drove, went (instantly) |

The indefinido also takes its point of view from the present, but the events observed took place often, or it lasted longer, so that one does not describe a point in time, but a period of time. Since the time of the event cannot be precisely defined, it is called "indefinido". The speaker uses the indefinido to describe the (singular) event or happening, but without attempting to describe the framework of a situation more precisely or to verbally express an executive context for what is (singularly) described. - Examples:

Llegué a las seis de la mañana, tomé una ducha y me fui a la cama. – „Ich kam im Moment um sechs Uhr früh morgens an, nahm ein Duschbad und ging ins Bett.“

Then with previous actions, actions or facts in the past with consequences and consequences in the past.

Salí del trabajo, llegué a casa y me fui derecho a la cama con mi novio. – „Ich ging von der Arbeit zurück, kam nach Hause und ging schnurstracks mit meinem Mann ins Bett.“

The Pretérito imperfecto does not want to make any direct reference to the presence of an event, nor does it say anything about the beginning and the end of an event as such. It merely states the reference to the impermanence or "past nature" of facts. - example:

La gente que venía de lejos narraba historias de la guerra. – „Die Leute die von weit her kamen erzählten Geschichten über den Krieg.“

It “condenses” physical, emotional and mental fields of meaning into facts and projects or locates them as linguistic utterances in the past. In a sense, it represents a “narrative mass ”, masa de narración , which was located in a past. - Examples:

Estábamos muy cansados pero teníamos que bregar. – „Wir waren sehr müde aber wir mussten uns abrackern.“ El bebé tenía hambre constantemente. – „Der Säugling hatte immerfort Hunger.“ Tenían una casa. – „Sie hatten ein Haus.“ Le conocía bien. – „Ihn ich kannte gut.“

But

Conocía a Denis Diderot. – „Ich kannte Denis Diderot.“

There is no exact information about the temporal limitation of the events and actions to the indicated past or " pastness ". - Examples:

Sentado en el muelle de la bahía. Veíamos cómo los barcos entraban en el puerto de San Francisco. – „Sitzend an der Kaimauer der Bai. Wir sahen wie die Schiffe in den Hafen von San Francisco einfuhren.“ Cuando iba de trabajo comí algo. – „Auf dem Weg zur Arbeit aß ich ein wenig.“

The imperfecto is used for the general description of a state or a situation. Example: De muy joven, Susana era muy viva. In her earliest youth, Susanne was very lively. It is used to express the habitual sequence of repetitive actions, processes or facts in language. - Examples:

Cuando venía mi hermano traía obsequios. – „Immer wenn mein Bruder kam, brachte er kleine Aufmerksamkeiten mit.“ Me encantaba hacer el amor con mi novio. – „Mir gefiel es mit meinen Freund Liebe zu machen.“ Tus padres siempre leían el periódico dominical por la mañana. – „Deine Eltern immer sie lasen die Sonntagsmorgenzeitung.“ Antes tenía una vida como la tuya en Chile y ahora no tengo nada. – „Früher hatte ich ein Leben wie das Deinige in Chile und jetzt nicht ich habe garnichts.“

In the Pretérito indefinido there are unique , perfective punctual actions in the past (see aorist and type of action ). It has no equivalent in German and is given in a translation with the past tense . Only by determining the time within the sentence can one see which form was chosen; so there are clear rules regarding the different uses of these times. The speaker's attitude, the point in time at which the exact temporal structures are viewed is called the aspect or type of action of actions or events and thus determines the imperfect or perfect aspect .

If one compares the Pretérito indefinido with the Pretérito imperfecto , it turns out that both times express the aspects either as completed actions or events in the past or not. In other words, they are forms that are capable of expressing past perfection or past imperfection.

For events and processes that happened once - the point in time for the speaker is closed and ideally determinable, but not clearly limited in time - or for events that have taken place more than once but are also to be regarded as closed, the pretérito becomes used imperfecto .

In the Pretérito imperfecto , states are told (e.g. panoramic descriptions , weather phenomena, landscapes , properties of objects, but also people ) and descriptions of the situation and background are provided. If a new action in the past is accompanied by the action already in progress or another event running in parallel, this tense is also selected. But when an action or event that was in progress is affected by another incipient action, the incipient action is in indefinido . The ongoing event is still in the imperfecto . - example:

María hacía un jersey de punto cuando llegué a casa. – „Maria strickte einen Pullover, als ich nach Hause kam.“

This means that German formulations can be thought of as always, continuously, persistently, persistently, continuously, endlessly, all time, eternally, continuously, anytime, every time, continuously, always, always when, as usual, as usual, continuously or as always .

In Spanish, the aspect finds its isolated expression in the pair of opposites Pretérito indefinido versus Pretérito imperfecto , morphologically the tense morphem coincides with the aspect morphem. The indefinido denotes an event or an action that has ended in the past (perfect aspect). The imperfecto, on the other hand, lacks this determination (imperfective aspect), here the end of the event or action can remain open. Relative to the end of the event of completing a sweater (hacía) , the arrival home (llegué) and its implications are not finished. - example:

Cuando llegué, mi esposa ya se había ido. – „Als ich ankam, war meine Ehefrau schon weg.“

The verb llegar is in the tense of the Indefinido llegué , the progression of the action then in the Imperfecto había ido . With regard to the aspect, the verb llegué in indefinido describes a finished event (perfect aspect), with había ido the imperfecto, however, the determination (imperfective aspect) remains open.

The “time markers” for using the Pretérito indefinido or the Perfecto simple are the following words: ayer , anteayer , el lunes , el martes , hace un año , el otro día , ese / aquel día , el domingo , hace un rato , la semana pasada , el mes pasado , el año pasado . So for all temporal determinations with pasado or pasada the indefinido is used. - example:

Ayer María se compró un coche. – „Gestern Maria sich kaufte einen Wagen.“

The indefinido and the imperfecto can be combined in one text from a stylistic point of view. This is the background to the action, the framework in the imperfecto . The words introducing the tense form, such as mientras , porque , siempre , are then placed in front of a verb conjugated in the past tense, while words like enseguida , luego , un día , de repente introduce the change in the course of events in the narrative, and then at this point with a Verb to continue in indefinido . - example:

Mientras yo hablaba con mi novio llegó mi hermana.

The imperfecto is used for the event or action that is presented in its not clearly defined duration and serves as a background for an incipient (punctual) and thus temporally limited fact . If one wants to give the event a reference to the present or to the future, preference is given to the Pretérito perfecto or perfecto compuesto . - Examples:

No estaba en casa cuando llamaste. Cuando estábamos durmiendo ha llovido a chorros.

If an event or an action interrupts another fact, the interrupting action is in the indefinido , ¿Qué pasó? the interrupted fact in the Imperfecto ¿Qué fue? - Examples:

Mientras nosotros veíamos la televisión, sonó el teléfono. El sábado por la mañana estaba trabajando cuando llegó él a mi despacho. – „Der Samstagmorgen ich war gerade arbeitend, als er kam in mein Büro.“

The indefinido, he answers the question ¿Qué pasó? What happened? ; is used to denote a one-off, completed in the past, no longer affecting the present action as well as newly occurring or successive events in the past. - example:

Su esposa murió en 1796.

If no time indications are used in a verbal sentence or if such a time cannot be deduced from the context , the pretérito perfecto is used, especially if the action or event to the speaker is perceived as being relatively close to the present . However, if the action or event that is being talked about was long or longer ago, or if it is part of a more distant past for the speaker, the indefinido is used . If, however, two or more events are told that happened at the same time in a past, the imperfecto is used to describe the event that is still going on, the framework action , while the indefinido is used for each new action that occurs. In other words, if a narrator begins in indefinido , the content of his narration is usually not elaborated further, unlike the introductory imperfecto , where more detailed explanations of the subject matter of what is said often follow.

So: The pretérito indefinido is used for completed situations or actions in the past, whereby the frequency does not play a role, or for actions that have taken place in the past . It represents a typical time for storytelling , the tiempo narrativo . - Example:

Nuestro amigo salía de su casa, cuando le asaltaron unos ladrones. – „Unser Freund verließ sein Haus, als ihn Räuber überfielen.“

The verb "salir" is in the imperfecto and the verb "asaltar" in the indefinido .

If the individual actions are completed and these are linked to a chain of actions, then the indefinido is in both sequences. - example:

Ayer, cuando regresé a mi castillo encontré al caballero negro. „Gestern als ich ankam auf meiner Burg, traf ich den schwarzen Ritter.“

It follows:

El caballero negro estaba en su castello. „Der schwarze Ritter befand sich auf seiner Burg.“

If the first action began before the second action, and if the first action was not completed before the second, the first action sequence is reproduced in the imperfecto .

Ayer, cuando regresaba a su castillo encontré al caballero negro. „Gestern als ich zurückkehrte auf seine Burg, traf ich den schwarzen Ritter.“

It follows from this:

El caballero negro estaba en el camino. „Der schwarze Ritter war am Wege.“

"You are on your way", "Returning to the castle" represents the unfinished background story. The conjugated verb used is dynamic, durative and atelic in terms of its type of action , because no time frame is set in "Returning to the castle" , it is still complete. The “encounter of the black knight” is a punctual act, after all an encounter is already over when they enter. By using the imperfecto in the second example, the narrator indicates that he is on the way, that is, has not yet reached his destination, that the action is still going on.

The pairs of opposites pretérito imperfecto and pretérito perfecto (compuesto) or pretérito indefinido

The pretérito perfecto (compuesto) is a tense of presence. This means that, as with the perfect tense in German , one cannot speak of "earlier", but rather of "before". The adverb “before” refers to a prematurity, anterioridad , that is, actions that have taken place that are still related to the present or, better, to the time of speaking.

A fundamental need of every speaker of a natural language finds its expression in the fact that both temporal references and personal attitudes are promised in statements about the world.

Events, happenings or facts can be classified as past, present or future on a presented “ time line ” or “ time line ”. There are three time levels : presence, presente , past pasado and futurity futuro . In addition, however, these entities can still be related to one another. The resulting relationships are the temporal relationships : Post-temporality (“after”), posterioridad , simultaneity (“now”), simultaneousidad and prematurity (“before”), anterioridad .

Cuando estábamos en el jardín nos trabajábamos todos los días. Als wir waren im Garten wir arbeiteten den ganzen Tag. Das Pretérito imperfecto stellt in der Vergangenheit unbegrenzt sich wiederholende Vorgänge oder Zustände dar. He trabajado durante toda la noche. Ich habe gearbeitet die ganze Nacht. Das Pretérito perfecto compuesto stellt einen Vorgang oder Zustand dar, dessen Beginn oder Abschluss vor dem Augenblick des Sprechens liegt, dessen Ergebnis aber noch von Bedeutung ist. Empecé a trabajar a las seis. Ich begann zu arbeiten um sechs Uhr. Das Pretérito indefinido bezeichnet den Beginn (oder auch Ende) eines Vorgangs oder Zustands.

For the inflected languages , the verbal categories of tense and mode are available. They are one of the most important instruments for establishing such references. Even more, in the inflected languages the marking of a verb according to mode and tense is absolutely essential in order to make a grammatically correct and understandable statement.

The mode enables the speaker to present his or her subjective attitude to the matter to be said or, according to Jacob Wackernagel, to describe the relationship between activity and reality.

The unmarked mode is the

- Indicative, modo indicativo . He posits the action or event as real.

The other modes are:

- Subjunctive It sets the action as possible.

- Conditional It sets the action as conditional.

- Imperative He sets the action as ordered.

The modes reflect the subjective attitude, conditionality, i.e. connections between objects and the representations in human consciousness as well as the request.

In contrast to the tense (i.e. the time stage), the aspect does not refer to the point in time of the process relative to the moment of the statement (past, present, future), but to the way in which this process is viewed (i.e. the reference to the direction of time or the time conditions).

However, the terms tense and aspect are not clearly distinguished from one another in all languages. This has to do with the fact that there are languages in which the aspect distinction is expressed morphologically only in past tenses, so that the aspects coincide with the tense names. For example, the Latin imperfect tense is a past tense in the unfinished aspect (hence the name). Other languages morphologically only distinguish the aspect and do not have any basic categorization in time levels. In still other languages, time levels and aspects are systematically combined with one another so that three time levels exist for each aspect. German, on the other hand, has a tense system, but no grammatical category of the aspect, but there are certainly possibilities to reproduce aspectuality.

With the tenses, the speaker is given the opportunity to use morphological means to realize temporal relations to the content of what has been promised at the moment of speaking . The tense is the most differentiated category of the Spanish verb. The setting of the tense is not a linguistic time measurement and therefore does not indicate when an event or an action takes place, because physically and temporally different events can be characterized by the same tense. - Example on the Futuro simple :

Operaré mañana. – „Ich werde operieren morgen.“ bzw. „Ich werde morgen operieren.“ Oder Operaré dentro de un año. – „Ich werde innerhalb eines Jahres operieren.“

Through the tense, a speaker assigns an event or an action from the perspective of a passing time (time relation) to a reference point, punto de referencia R ( time relation or consecutio temporum , also sequence of times). The verb “operate” in the sentence example Operaré mañana or Operaré dentro de un año is formed after the speech situation. The verb “operar” experiences a morphological-grammatical change; the 1st person singular of the Futuro simple is conjugated. The dimensions of the perceptual space to be promised for the events consist of two items: the time relation and the reference point. Because the tense refers to a point of reference, it gains a temporally deictic value - a property that the aspect does not have. By adding the adverb “mañana” or the temporal preposition “dentro de un año”, the reference point is given a lexical-semantic definition.

In Spanish, the category of aspect is used to define the pair of opposites pretérito imperfecto for the unfinished event and the pretérito perfecto (compuesto) or pretérito indefinido for a completed action . While in the imperfective aspect the temporal boundaries of the event are not seen, in the perfective aspect the event including its boundaries is seen as a whole. In Spanish, however, the terms tense and aspect are not as clearly separated from each other as in the Slavic languages . This is because the aspect distinction is expressed morphologically only in the past tenses, so the aspect coincides with the tense designations. Nonetheless, when considering the aspect, the focus is not on the "time levels", ie the tenses, but rather the temporal structure of actions, the "reference to the direction of time". For the aspect, it is decisive what extent an action has, whether it is completed or is still ongoing and how the speaker is integrated into this situation. If one follows Reichenbach's considerations, then a perfect aspect would exist if the reference time R includes the event time E or follows it . If the reference time R is included in the event time E , one speaks of an imperfective aspect. - example:

Mi padre corría a la habitación lateral. – „Mein Vater rannte in das Nebenzimmer.“ Präziser: „Mein Vater war noch dabei in das Nebenzimmer zu rennen.“ Imperfektive Handlung als im Verlauf befindlich versprachlicht. Mi padre corrió a la habitación lateral. – „Mein Vater rannte schon ins Nebenzimmer.“ Perfektive Handlung als abgeschlossen versprachlicht.

The consideration of the "time direction with respect" is the possibility with the perfective aspect , pretérito indefinido three different types of actions (see also action type ) to promised union:

- a momentary or punctual action;

- a result or an effect, end-related;

- an incoative, initially related.

For the imperfective aspect , pretérito imperfecto we can specify four types of actions or events:

- a durative act without reference to the beginning or the end;

- an iterative action with no reference to the beginning or the end;

- an inchoative act, without any reference to the beginning or the end.

- a conative act.

For Leiss (1992) the grammatical category of the aspect stands for a "perspective category". While she sees the difference between tense and aspect in that the tense localizes what is happening in a now-present, before-past, or after-future, in the aspect she sees the speaker localized. From a narrative point of view, the speaker can be either (visually) inside or outside a verbal event: For the “inner perspective” (“aspect of the imperfect”) the speaker is in a (imagined) past. For the “outside perspective” (“aspect of the perfect”) the speaker imagines a process as complete and makes no reference to its course or its result.

Erwin Koschmieder's reference to time and language

Erwin Koschmieder uses his terminology to relate time and language. A contribution to the aspect and tense question. (1928) compared the “time value”, the “I” or “self-consciousness” with the “reference to the direction of time”. A relationship of the “time step reference” can be described by the “time value” and the “I”. The “time step reference” of the past, present and future arises when a “fact” (or to a certain extent an action) is defined in relation to the situation of the “time value” to the speaker (time steps). Here, the “temporal value” of a “fact” (or to a certain extent an action) is then promised as past, future or present ( tense system ) according to its position in relation to the “present point” on the (virtual) “timeline” .

With the "time direction reference", however, the aspect system is recorded (time relationships). Because with the type of temporal relationship in which a “fact” is placed, the speaker defines a relationship between the “I” and the “fact”, the “time directional reference”, due to the meaning of the verbal statement. This relationship leaves two options open for Koschmieder:

- The verbalized statement is directed from the past into the future. The “fact” is characterized as happening (see imperfective aspect ).

- The promised statement is directed from the future into the past. In this way one interprets the "state of affairs" as happened and grasps it in its totality (see perfect aspect ).

For Koschmieder there are facts with time value and facts without time value . Events with temporal value are individual, one-off events assigned to a defined location (see point 3 in the figure ) on the timeline. The events without temporal value are unlimited, repeated facts that are timelessly presented as events outside of time, so-called eternal truths. They do not mean an individual process and are not presented in a calendar - chronometrically through time measurement or time position information . One could translate Koschmieder's terms with individual-concrete and general-abstract facts .

Hans Reichenbach's description of the tense

Reichenbach defines the aspect "logically". Although the tenses are characterized by the "temporality," the spokesman or marked addressee in a communicative situation with the statement " I " ( here-now-I-Origo or deictic center) a deictic reference or starting point for his speech , therefore, the tenses do not correspond to the cognitive concepts of time or temporality in extra-linguistic reality or are to be equated with them. The horizontal time axis represents the reality or the reality of the speaker to a certain extent. The semantic reality is the experienced, "reflected" reality (see semantic network , knowledge , proposition ). For this purpose, the relationships are applied to a spatial metaphor , also a timeline , línea de tiempo for the representation of times, spaces and sequences in the form of a line and transferred to the resulting terminology ( local deixis ).

Hans Reichenbach (1947) created a terminology for understanding the verbal sequence of tenses, the deictic and narrative tense functions. Deictic expressions are of elementary importance for the understanding of language, since the majority of linguistic utterances are only discriminated by a recipient if he can understand the spoken messages embedded in a personal, social, spatial and temporal context. The deixis as a semantic component refers to the relative orientation between the speaker location, a reference area and a reference area, which in turn is divided or differentiated into personal, spatial or time deixis.

- Examples: The local adverb aquí , here belongs to a different deictic conceptual system than ahora , now and thus to the contrast between locality and temporality. Antes , mentioned earlier , refers to a different time relation than pronto , soon . It describes the opposition between prematurity, anterioridad and post-temporality , posterioridad .

The tenses are therefore also deictic, i.e. H. their interpretation will depend on the time of speaking and the knowledge of the concrete utterance situation. The additional deictic relationship between speaking time S and event time E is a necessary prerequisite for this. In addition, the use of temporal adverbs determines the verbalized event, action or fact either compared to speaking time S about ayer , yesterday or compared to the reference time R about anteayer , the day before yesterday .

Reichenbach described the tenses as time stages by means of two relations between three reference or points in time. To characterize the different tense forms, the relation between the speaking time S , Spanish punto de habla H and the reference point R , Spanish punto de referencia R , as well as that between the event time E , Spanish punto del evento E and the reference point R was set .

In the approach he originally formulated , however, only temporal relationships between these three reference points could be described. According to Reichenbach, more than two points in time or time intervals are necessary to describe the tense. Reichenbach introduced the following categories:

- Speaking time or origio, utterance time, utterance time, communication time, speaking time, speech act, S point of speech or H punto de habla , it refers to the moment of verbalization by the speaker; in some cases it is also defined as a possible time span, in most cases it is a moment in time. It relates to the moment of speaking, it is deictically situated,

- Event time or situation time, act time, event time, action time E point of event , punto del evento , it is the time interval in which the verbalized state applies or the expressed action takes place, it can be both a point in time and a period of time. An event is a fact or fact that is tied to a time interval, it is also deictically situated,

- Reference time or viewing time, viewing time, reference time, reference point, R point of reference , punto de referencia , it is a time interval different from the speaking time. Reproduced by a "viewer". It points to an event, for example through a time adverb, or it refers to an occurrence in order to deictically localize it in time. The reference time and thus the time setting can be determined using temporal adverbs or from the narrative context. The reference time is the time relative to which the event is classified as premature, late or temporally associated. In this way, it refers to or discriminates between prematurity, anterioridad and post temporality, posterioridad , the reference time can either coincide with the speaking time or with the event time, or with both. The reference time can also be separated from both so in the past perfect.

- Under the talk time distance is the distance between the opening time S or H and the event time E .

A speaker promises or reports in an (interactive) situation about an event at the moment of speaking or the speaking time S by referring to a referential "Now" or a reference point in time (reference point R ) - in the sense of a spatial metaphor as a timeline - localization or localization of the reported event succeeds. The tenses thus refer to the reference point in time or the reference time R , two considerations are important:

- did the event (event time E ) happen before , in parallel or after the reference time (reference time R );

- is the reference time ( R ) before , after the narration moment (speaking time S ) or both coincide .

A tense is then the localization or location of an event E in relation to a reference time R . In terms of spatial metaphors, the timeline, the direction “before” or “after” is decisive, but not an absolute distance that is based on a physical time measurement , for example . The relationship or ratio of the reference time, R to talk time, S is described with the terms "past" (RS), "Presence" (S, R) and "Zukünfigkeit" (SR), the relation of the event time, E at the reference time R is one by the terms “prematurely” (ER), “simultaneously” (R, E) and “afterwards” (R, E).

In the time relation of the past, the reference time R completely precedes the speaking time S ( E <S ). In the time relation of the present, speaking time S and reference time R ( E = S ) overlap . In the time relation of the future, the speaking time S precedes the reference time R ( S <E ).

- E, RS (H) (E = R <S) Pretérito perfecto simple or Pretérito indefinido, example: salió

- E, RS (H) (E = R <S) Pretérito imperfecto, example salía

- ER, S (H) (E <R = S) Pretérito perfecto compuesto, example: ha salido

- S (H), R, E (E = S = R) Presente, example: sale

The tense locates the reference time R relative to the speaking time S , while the aspect locates the event time E relative to the reference time R.

The Indefinido and Pretérito perfecto compuesto give sprechzeitvorzeitige events S , acts or facts again, they are but a reference time different R . The reference time R of the Pretérito perfecto compuesto is the present, that of the indefinido , the past. A reference time reference is reproduced through the use of temporal-deictic adverbs or based on the determination of the speaking time distance. The speaking time distance describes the distance between the speaking time S and the event time E , whereby the indefinido is seen as remote from the speaking time , the pretérito perfecto compuesto as being close to the speaking time . The speaking time distance can generally be mapped in the form of a "greater than relation" between the different lengths of time. The Pretérito pluscuamperfecto de indicativo and the Pretérito anterior de indicativo give a precise distinction between the prematurity and the immediate prematurity. For the pretérito imperfecto , the positioning as a past tense has less relevance, although the reference event begins early, it does not necessarily end early.

The integration of the concept of aspect into Reichenbach's considerations

Further developments of his theory were then also able to explain more complicated descriptions of the past tenses, such as that of the imperfect tense . Since the Spanish indefinido and imperfecto, as an essential pair of oppositions, do not, strictly speaking, express different time stages in this aspect language, but denote different, completed processes that are characterized with a definable duration as an action in the past, extensions had to be included in Reichenbach's considerations. Different, completed processes on the timeline denote that which is also referred to with the concept of the aspect. The consideration of the actions from the point of view of the aspect leads to the abolition of the original Reichenbach's point view of speaking time S and event time E, which thus changes into a view in which these "times" can be viewed as extended, i.e. as "time intervals" .

The essential property of the aspect in connection with the indefinido and imperfecto is that the former expresses perfective, closed events and the following imperfective, non-closed events, states or facts. The concept of aspect forces Reichenbach's idea of a selective view of speaking time S and event time E into an expanded view in which the points in time are viewed as extended or as time intervals. According to Becker (2010), a possible distinction between the two aspects is given by the description “ ⊆ ” , this symbol stands for the relation of abstinence.

- Pretérito indefinido : perfect: E ⊆ R , d. H. the event time E is in the reference time R included.

- Pretérito imperfecto : imperfect: R ⊆ E , d. H. the reference time R is the event time E contained.

These two tenses are not about the difference in temporality, but in aspect . Perfective forms record the verbal action as a completely completed process with a definable duration (point in time). Imperfective forms record the development of the verbal action and put it in the foreground without indicating the end of the same (period). So it's about the difference between period and point in time. Depending on whether the reference time R that is being talked about is contained in the time of the situation, the event time E or vice versa, a distinction is made between the perfective and imperfective aspects. In Spanish, however, the terms tense and aspect are not as clearly separated from each other as in the Slavic languages . This is because the aspect distinction is expressed morphologically only in the past tenses, so the aspect coincides with the tense designations. Nonetheless, when considering the aspect, the focus is not on the "time levels", ie the tenses, but rather the temporal structure of actions, the "reference to the direction of time". For the aspect, it is decisive what extent an action has, whether it is completed or is still ongoing and how the speaker is integrated into this situation. If one follows Reichenbach's considerations, then a perfect aspect would exist if the reference time R includes the event time E or follows it . If the reference time R is included in the event time E , one speaks of an imperfective aspect.

literature

Hispanic Studies

- Hans-Georg Beckmann: New Spanish grammar. dnf-Verlag, Göttingen 1994, ISBN 3-9803483-3-4 , p. 160.

- Horst Combe: The use of the Spanish subjuntivo in relative clauses. Dissertation . University of Tübingen, 2010 ( online ).

- Bernard Comrie: Aspect. An Introduction To The Study Of Verbal Aspect And Related Problems. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1976, ISBN 0-521-21109-3 .

- Elena González, Blanco García: La didáctica a extranjeros de la sintaxis escrita. Las oraciones de relativo en español. Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, Instituto de la Lengua Española, pp. 441–451 (restricted access: online ).

- Wolfgang Halm: Modern Spanish short grammar. Max Hueber, Munich 1987, ISBN 3-19-004020-6 , pp. 192-197.

- Klaus Heger: The designation of temporal-deictic conceptual categories in the French and Spanish conjugation systems. Max Niemeyer, Tübingen 1963

- Konstanze Jungbluth, Federica Da Milano: Manual of Deixis in Romance Languages. Vol. 6 Manuals of Romance Linguistics, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 2015, ISBN 3-11-031773-7

- Wolfgang Klein: Tempus, Aspect and Adverbs of Time. Kognitionswissenschaft 1992, Vol. 2, pp. 107–118 ( PDF Online; 126.8 kB ).

- Rainer Kuttert. Circle of Applied Linguistics / Círculo de Lingüística Aplicada a la Comunicación May 14, 2003. ISSN 1576-4737 . In: Peter Lang (Ed.): Syntactic and semantic differentiation of the Spanish tense forms of the past 'perf simple', 'perf comp' e 'imperfecto', Frankfurt am Main, 1982, ISBN 3-8204-7243-6 ( online website ) .

- Manuel Leonetti: Por qué el imperfecto es anafórico . In: B. Camus, L. García Fernández (eds.): El pretérito imperfecto. Gredos, Madrid 2003 ( online ). 3

- Meike Pöll, Bernhard Meliss: Current Perspectives in Contrastive Linguistics German - Spanish - Portuguese. Studies on Contrastive German-Ibero-Romance Linguistics Books on Demand, Norderstedt 2015, ISBN 3-8233-6954-7 .

- Claudia Moriena, Karen Genschow: Great Spanish learning grammar: rules, application examples, tests; [Level A1 - C1]. Hueber Verlag, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-19-104145-8 , pp. 230-253.

- Stefan Ruhstaller: Acerca del sistema de los tiempos del español una categorizacion de distintos tipos de perfecto compuesto. CAUCE, Revista de filología y su didáctica, n ° 20-21, 1997-1998, pp. 997-1016 ( online ).

- M. Rafael Salaberry: The Development of Past Tense Morphology in L2 Spanish. Studies in Bilingualism, Vol. 22. John Benjamin Publishing, 2001, ISBN 90-272-9883-1 .

- Ulrike Schwall: Aspectuality. A semantic-functional category. Tübingen Contributions to Linguistics, Vol. 344. Gunter Narr Verlag, Tübingen 1991, ISBN 3-8233-4207-X .

- Alfred R. Wedel: Los concepts "perfectivo y perfecto" en el sistema verbal en el castellano moderno. Nueva Revista de Filologia Hispanica XXIII (1974), pp. 381-388 ( online ).

- Celia Berná Sicilia: La delimitación temporal en el verbo durar: un análisis valencial combinatorio. Verba hispanica XX / 1, pp. 13-29 ( online ).

- Lars-Georg Wigger: The history of the development of the Romanesque past tenses using the example of the Pretérito Perfeito Composto in Portuguese. Dissertation, University of Tübingen 2005 ( online ).

General considerations

- Olga Balboa: Langenscheidt. Verb tables Spanish. Langenscheidt KG, Berlin / Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-468-34345-2 ( digitized version ).

- Johannes Dölling: Semantics and Pragmatics. Temporal and modal meaning. Institute for Linguistics, University of Leipzig ( Online PDF; 114 KB ).

- Cathrine Fabricius-Hansen: Tempus fugit. About the interpretation of temporal structures in German. Language of the present, published on behalf of the Institute for German Language (Ed .: Joachim Ballweg, Inken Keim, Hugo Steger and Rainer Wimmer), Vol. LXIV, Schwann, Düsseldorf 1986, ISBN 3-590-15664-3 ( Online PDF; 7.7 MB ).

- Wolfgang Klein: Time in Language. Routledge, London 2014, ISBN 0-415-86956-0 .

- Erwin Koschmieder : Reference to time and language. A contribution to the aspect and tense question. Breslau 1928 (ND: WTB, Darmstadt 1971), ISBN 3-534-05775-9 .

- Manfred Krifka: Semantics. Sentence semantics 10 aspect. Institute for German Language and Linguistics, HU Berlin ( PDF Online; 267 KB ).

- Helena Kurzová: The relative clause in the Indo-European languages . Buske, Hamburg 1981, ISBN 3-87118-458-6 .

- Christian Lehmann : The relative clause. Typology of its structure, theory of its functions, compendium of its grammar . Narr, Tübingen 1984, ISBN 3-87808-982-1 .

- Sebastian Löbner: Approaches to an integral theory of tense, aspect and types of action. University of Düsseldorf, pp. 161–193 ( online PDF ).

- Alla Paslawska: Tempus-Aspect-Types of Action-Architecture from a typological point of view. Eberhard-Karls-Universität Tübingen, pp. 1–23 ( online PDF ).

- Karl-Ernst Sommerfeldt , Herbert Schreiber, Günter Starke: Grammatical-semantic fields of the German language of the present. Langenscheidt, Berlin / Munich / Leipzig, Leipzig 1991, ISBN 3-324-00549-3 .

- Karl-Ernst Sommerfeldt, Günter Starke, Dieter Nerius : Introduction to the grammar and orthography of contemporary German. Bibliographical Institute, Leipzig 1981.

- Hans-Jörg Schwenk: Aspectuality and Temporality - Aspect and Tense. Miscellanea. Acta Universitatis Lodziensis, Folia Germanica 8, 2012, pp. 131-149 ( online ).

- Karin Weise, Mathilde Bénard: The representation and communication of present, preterital and futuristic verbal forms of Portuguese, Spanish, French and Italian for German-speaking learners. University of Rostock ( online PDF ).

- Anke Grutschus: "¡No tengáis miedo!" Vs. “Don't be afraid!” A German-Spanish comparison around 'fear'. Cape. 3.3. Aktionart, p. 97. In: Petra Eberwein, Petra Eberwein, Aina Torrent, Lucía Uría Fernández (eds.): Contrastive Emotion Research. Spanish German. Workshop from June 10, 2010–12. June 2010, Cologne / Colonia, Cologne University of Applied Sciences ( PDF Online 2 MB ).

Scientific individual work

Hispanic Studies

- Helmut Berschin : Past tense and perfect usage in today's Spanish. Vol. 157 Supplements to the journal for Romance philology, Max Niemeyer, Tübingen 1976, ISBN 3-484-52062-0 .

- Juan Moreno Burgos: El pretérito perfecto compuesto en el ámbito hispánico. Anuario de Letras. Lingüística y Filología, volume III, 1, año 2015: 87–130 ( Online PDF )

- Juan Moreno Burgos: Estatividad y aspecto gramatical. Dissertation University of Regensburg 2013 ( online PDF ).

- Alejandro Castañeda Castro: A specto, perspectiva y tiempo de procesamiento en la oposición imperfecto / indefinido en español. Ventajas explicativas y aplicaciones pedagógicas. Recibido on November 26, 2006, Ræl 5 (2006): 107-140, ISSN 1885-9089 ( online ).

- Alicia Cipria, Craige Roberts: Spanish imperfecto and pretérito: Truth conditions and aktionsart effects in a Situation Semantics. Natural Language Semantics, December 2000, Volume 8, Issue 4, pp. 297-347 ( Online PDF ).

- Gibran Delgado Díaz, Luis A. Ortiz López: El pretérito vs. el imperfecto: ¿adquisición aspectual o temporal en 2L1 (criollo / español) y L2 (español)? In: Kimberly Geeslin, Manuel Díaz-Campos (Eds.): Selected Proceedings of the 14th Hispanic Linguistics Symposium. Cascadilla Proceedings Project, Somerville, MA 2012, pp. 165-178 ( online ).

- Ángeles Carrasco Gutiérrez: Reichenbach y los tiempos verbales del español. DICENDA, Cuadernos Filologíca Hispánica, № 12, 69–86, Edit. Complutense Madrid 1994 ( online ).

- Ilpo Kempas: Estudio sobre el uso del pretérito perfecto prehodiernal en el español peninsular y en comparación con la variedad del español argentino hablada en Santiago del Estero. Dissertation, Universidad de Helsinki, Helsinki 2006, ISBN 952-91-9605-9 ( online ).

- Margaret Lubbers Quesada , Ricardo Maldonado: Dimensiones del aspecto en español. Publicaciones del Centro de Lingüística Hispánica, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), Ciudad de México 2005, ISBN 9-7032-2303-6 .

- Juan Rafael Zamorano Mansilla: La generación de tiempo y aspecto en inglés y español: un estudio funcional contrastivo. Departamento de Filología Inglesa I, Universidad Complutense, June 2006 ( Online PDF ).

- Pilar Elena: La interpretación del preterite en la traducción al español. Universidad de Salamanca, pp. 1–14 ( online PDF ).

- José P. Rona: Tiempo y aspecto: análisis binario de la conjugación española. XVIII Congreso de The International Linguista Association (Arequipa, Perú, marzo de 1973), pp. 211-223 ( online ).

- María de las Nieves Vázquez Núñez: Tense, Mode and Aspect in Sixteenth Century Spanish. The Chronicle of Alonso Borregán. Dissertation, Albert-Ludwigs-University Freiburg i. Br., Freiburg 1998/1999 ( online ).

- Montserrat Veyrat Rigat: Aspecto, perífrasis y auxiliación: un enfoque perceptivo. Publicaciones de la Universidad de València, València, 1993, ISBN 8-4604-8354-1

- Guillermo Rojo : Relaciones entre temporalidad y aspecto en el verbo español. In: Ignacio Bosque (ed.): Tiempo y aspecto en español. Catedra, Madrid 1990, pp. 17-42, ISBN 84-376-0946-1 ( online PDF ).

General work on the topic

- Abraham P. Ten Cate: How many tenses does German have? In: ojs.statsbiblioteket.dk, pp. 83-90 ( online ).

- Pier Marco Bertinetto, Sabrina Noccetti: Prolegomena to ATAM acquisition. Theoretical premises and corpus labeling . Quaderni del Laboratorio di Linguistica, 2006, Vol. 6 ( Online PDF; 260 KB ).

- Richard Schrodt: Perspectives of Subjectivity: The relationship between system time and proper time in the perfect tense forms. In: F. Stadler, M. Stöltzner (Eds.): Time and History. Time and history. Ontos Verlag, Frankfurt / Lancaster / Paris / New Brunswick, 2006, pp. 317–335 ( Online PDF; 128 KB ).

- Johannes Dölling: Imperfect. States, processes or time intervals? University of Leipzig, Semantics Colloquium, October 14, 2010, pp. 1–27 ( online PDF ).

- Juan Aguilar González: El imperfecto y el indefinido español. May 2015, pp. 1–94. ( Online PDF ).

- Olaf Krause: On the meaning and function of the categories of the verbal aspect in language comparison. University of Hanover, pp. 1–31 ( online PDF ).

- Justo Fernández López: Indefinido. Hispanoteca ( online PDF) .

- Justo Fernández López: The times of the past - Tiempos narrativos. Spanish grammar 1. The narrative tenses in Spanish. Hispanoteca. ( Online PDF ).

- Justo Fernández López: The times of the past - three special cases of interplay imperfecto - indefinido. Hispanoteca ( online PDF ).

- Wolfgang Hock, Manfred Krifka: Basic concepts: tense, aspect, type of action, constitution of time. In: Wolfgang Hock, Manfred Krifka (ed.): Aspect and Constitution of Time. WS 2002/3, Institute for German Language and Linguistics, Humboldt University Berlin, 2002 ( online ).

Web links

- Justo Fernández López: The times of the past in Spanish - Los tiempos narrativos en español.

- Justo Fernández López: Verbos estativos - Imperfecto - Indefinido

Individual evidence

- ↑ The Spanish verbal system - Sistema verbal español. Justo Fernández López, Hispanoteca