Subjunctive

The subjuntivo or modo de subjuntivo (" subjunctive ") is a mode or a statement in the grammar of the Spanish language . In general terms, the modes provide information about the relationship between the event described by the speaker and reality .

The French subjonctif is a mode of the French language , it has a lot in common with the Spanish subjuntivo . Other forms corresponding to this mode can also be found in other Romance languages , for example in Italian congiuntivo , Portuguese subjuntivo o conjuntivo, Romanian conjunctivul or Romansh conjunctiv .

The mode as a morphological category of the verb is considered a means of expressing the modality . In particular, the modality expresses whether the verbalization of the content of consciousness as an expression of the speaker's individual reality can ultimately be seen as in accordance with reality or not ( frame of interpretation ). In the modality it comes from a pragmatic point of view to a spokesman attitude towards its intended utterance that can be done not only by means of the aforementioned modes (indicative vs. subjunctive), but also by modal verbs and -Adverbs and also by means of some tenses like the past tense and Condicional promised light which then more or less implicitly indicate the modal meaning.

The two “basic modalities” reality (indicative) and non-reality (subjunctive) are derived from this. With its subjective expression within these two "basic procedures", the speaker utters according to the rules of the degree of certainty or uncertainty of the assumption , debt, the possibility or impossibility of conditionality of a presentation content .

The Spanish term “subjuntivo” (like the French term “ subjonctif ”) goes back to the Latin word subiungere , which means “to add”, “add”, “connect”, but also “subjugate” or “subjugate”. This designation highlights the fact that it is typically a dependent verb form that appears in certain types of subordinate clauses, oraciones subordinadas . Uses of the subjuntivo in main clauses , which also exist alongside them, are therefore regarded as less typical.

Difference between indicativo and subjuntivo

For Hummel (2001), the indicative is the mode of presentation, representation of events in the “ mode of existence ”; just as the facts are after they have occurred - after they have actually occurred - so it describes the course of events on the (temporal) axis of reality. That is why the tense system and the aspect are more differentiated and developed in the indicative . Because existent things exist only because of its occurrence and as verbs ultimately define events, the modes can also be understood as forms of presentation of events. The indicative thus encompasses the events from the perspective of their occurrence, i.e. from a cognitive and epistemological perspective with the question of their factual existence.

The subjunctive, on the other hand, captures the events from the perspective of their (possible) occurrence or their incidence, whereby the fact of their occurrence as such is abstracted or disregarded if the subjunctive is related to an event that actually occurred. The subjunctive presented the events in the "incidence mode" of an event, a state of affairs is focused through the perspective of its possible occurrence. The "incidence mode" of the subjunctive sets the event in motion with its verbalization, focuses the dynamics of its occurrence, but without describing the actual course of the event. From this perspective, the subjunctive shows itself as a possible form of representation or presentation of (presented) events, in which the focus is on the occurrence as such - an occurrence or as an abstraction of an occurrence, detached from its actual actualization. As a result, the subjunctive as a mode implies the existence of “entry alternatives”. He said nothing about the actual occurrence of an event in the "actual world", but he summarized the events as they might or might not have occurred in the other ( counterfactual ) "possible worlds" (see also counterfactual assumptions ). This shows the linguistic closeness or the connection to alternative events, so one formulates the hopes , worries , expectations , wishes , fears, etc. in everyday life . Ä. m .; one “wishes” or “honors”, “longs” and “hopes for” certain events and their occurrence; the updated verb forms are representations of the forms of events.

As a finite verb word forms are referred to a verb. They show or express certain grammatical features. The finite features of a conjugated verb, verbo conjugado (conjugation morpheme ) are the modus, modo , number, número , person, persona and the tense, tiempo . While the time reference can be depicted sharply in the indicative mode, it remains rather blurred in the forms of the subjunctive and requires contextual clarification. From this it can be deduced that the subjunctive, in comparison to the indicative, has a lower degree of “finity”.

A flexion morph , more precisely conjugation morph , results in synthetic and analytical (verbal) word formations. The number of different forms is less for the subjunctive than for the indicative, for this reason alone the verbalization of temporal relations cannot be the main function of the subjunctive.

This leads to a further difference between the two verbal categories, categorías verbal indicative and subjunctive, which is that the indicative mode can be viewed as a personal and temporal mode. It updates a process and situates it in a certain temporality ( temporal deixis ) by means of the various tenses ; it is the “temporal mode” par excellence. He objectifies facts and differentiates them in time.

The subjunctive is, so to speak, a “non-temporal mode”, as it cannot firmly locate a process or fact in one of the three categories of temporality such as past, present, future, but rather describe temporal relationships. While the forms of the indicative are able to express the absolute time level clearly and unambiguously, to a certain extent, in the “times” of the subjunctive, past, present and future merge. This means that one and the same temporal form of the subjunctive, depending on the context or relation , becomes temporally ambivalent or even plurivalent. - example:

Quería que llegaras. Ich wünschte, dass du noch kämest. Pretérito imperfecto de indicativo + Pretérito imperfecto de subjuntivo „rückdeutsch“

The subordinate clause, oración subordinada “que llegara” can refer to a (as yet undetermined) past, as well as to a present or future.

Another example:

Ay mi amor ya quiero que llegues. Oh meine Liebe schon ich wünsche, dass du kommest. Presente de indicativo + Presente de subjuntivo

Nevertheless, one distinguishes formally or the subjunctive can be set in six tenses, three simple and three compound tenses. - Examples of speaking with hablar :

- Presente de subjuntivo : hable

- Pretérito imperfecto de subjuntivo : hablara or hablase

- Pretérito perfecto de subjuntivo : haya hablado

- Pretérito pluscuamperfecto de subjuntivo : hubiera or hubiese hablado

- Futuro perfecto de subjuntivo : hablare

- Futuro perfecto de subjuntivo : hubiere hablado

Since there is no grammatical form in the subjuntivo for a perfect aspect , such as a pretérito indefinido , this aspect opposition does not apply. This means that a (grammatical) distinction between a (completed) state and a process is not possible.

If the subjunctive is used in the subordinate clause, as is usually the case, its use follows the temporal structure of a complex Spanish sentence and its fixed specifications. A characteristic of a subordinate clause is that it is introduced with a typical word, the subjunction , such words subordinate sentences to other sentences.

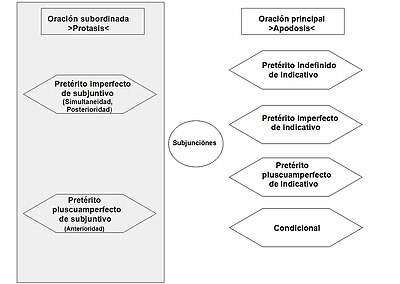

Since the tense in the subordinate clause (protasis) always depends on that of the main clause ( apodosis ), the recipient (listener, reader) is obliged to pay particular attention to the tense of the verb in the main clause. If the verb is in the main clause (Apodosis) in the Presente de indicativo , Futuro simple de indicativo or Pretérito perfecto de indicativo , the verb of the subordinate clause (Protasis) must be used in the Presente de subjuntivo or Pretérito perfecto de subjuntivo . If the verb in the main clause (apodosis) is in a past tense, such as the Pretérito indefinido de indicativo , Pretérito imperfecto de indicativo , Pretérito pluscuamperfecto de indicativo or in a condicional simple or condicional perfecto , the pretérito imperfecto plus or pretaméperfecto de subjetjperfecto de subamérito de subjuntivo are used.

Temporal relationships

The time relationships are therefore not of the same importance in the subjunctive as in the indicative. More applies to the indicative than to the subjunctive: which tense is chosen generally depends on the temporal relationship between the subordinate clause (protasis) and the superordinate clause (apodosis). The grammatical category of "tense" results in a structure that is not directly related to (real, physical) time , but always has to be related to the speaking time S (event time E - speaking time S - reference time R ) and relations can express (prematurity - simultaneity - laterality).

The subjunctive can also be seen as a mode of interpretation . Thus the use of the different tenses in the subjunctive does not depend on a (real) temporality, but rather on the use of the tense in which the verb of the main clause (apodosis) is used as well as the temporal relationship or relation of prematurity , simultaneity or posteriority between main clause Apodosis) and subordinate clause (protasis). The event time E point of event , punto del evento describes the time interval that depicts the three possible relationships between two points in time or time levels using the terms pre- timeliness , simultaneity and post- timeliness ; they are usually used to describe the relationship between the main and subordinate clauses. Therefore, strictly speaking, it is not correct to speak of the tenses of the subjunctive.

Prematurity, anterioridad

Prematurity occurs when the event expressed in a subordinate clause (protasis) takes place before the event narrated in the main clause (apodosis) . - example:

Después de que hubiéramos llegado, salió el autobús. Nachdem wir wären angekommen, fuhr der Bus ab. Hubiéramos llegado. El autobús salió.

Simultaneity, simultaniedad

Simultaneity exists when the event expressed in a subordinate clause (protasis) takes place simultaneously with the event expressed in the main clause (apodosis), one speaks of simultaneity. - example:

Leía el periódico mientras tu veías la tele. Ich las die Zeitung, während du sahst Fernsehen. Leía el periódico. Veías la tele.

Postponement, posterioridad

If the event expressed in a subordinate clause (protasis) takes place after the event expressed in the main clause (apodosis), one speaks of post-temporality. - example:

Es una pena que no hayas venido a la cena. Es ist schade, dass du nicht habest gekommen zum Abendessen.

The event of the dinner is long over, so that this event can no longer be influenced.

Since the subjunctive does not indicate time in the proper grammatical sense, it gives expression to the aspects of the incomplete process or the completed process.

The modes reflect the subjective attitude, conditionality, i.e. connections between objects and the representations in human consciousness as well as the request. The American linguist Matte (1988) relates the individual modes to cognitive processes , more precisely to a different degree of abstraction that they exhibited or triggered by being different from one another. According to their degree of abstraction, he arranged the modes as follows:

- Indicative, indicativo

- Imperative, imperativo

- Subjunctive, subjunctive

- Conditional, condicional

- Infinitive, infintivo .

According to his considerations, the indicative is at the lowest level of abstraction, it represents reality and allows the speaker to classify the facts in time. The imperative expresses the will of the speaker and is therefore closer to the “timeless” modes (subjunctive, conditional, infinitive) than the clearly “time-bound” indicative. For this reason, the imperative is seen as a bridge between the indicative and the subjunctive. The subjunctive is on a further, higher level of abstraction, which, like the imperative, expresses the will ( commands , wishes , conditions , requests), but also formulates a number of other modalities, such as subjectivity (in judgments , opinions , convictions , Wishes, etc.) and doubt. Finally, the infinitive, as the non-inflected verb form, has the highest degree of abstraction. He names different types of verbal processes in an abstract way, detached from any temporal reference, and thus resembles the noun.

Overview

Use of the subjunctive

If a speaker uses the subjuntivo, it is usually less about describing a fact than about expressing the speaker's internal attitude, feelings or opinions and so on. This implies that the subjunctive is used more often when the occurrence of an event or fact can be presented as an alternative to another event. For the use of the subjunctive, events are focused from the special perspective of their occurrence; abstracted from their presence. It is about the coloring of the statement by the speaker himself. This explanation of the Romance subjunctive or Spanish subjuntivos gives rise to linguistic discussions and theories, according to the current linguistic research on the subjuntivo .

Further key words that are close to the term “subjunctive” or that are connected with the “incidence mode” can be: anticipation ; Future; Foreseeing; Hypothesis ; Virtuality ; Hope ; rudimentary tense structure; Dullness; virtual time; Temporal references are diffuse; Simultaneity coincides with posteriority ; Reduction of temporality to prematurity or non-prematurity; Uncertainty ; Uncertainty; Decision under uncertainty ; Subjectivity ; Eventuality; Alternatives ; Optative ; Wishes ; Doubt ; Wanting , commanding or prompting, fear or insecure thinking ; thinking, feeling opinion ; that which cannot be grasped in its concreteness ; Present facts as possible.

According to Dietrich (2008), the use of the subjunctive includes, above all, the finality , the potential and the unreal hypothetical condition, the negative assertion, the generalization, the reference to an event or a fact in the imagination, the expression of feeling and the time limitation of an action .

If the main verb (apodosis) is in a tense of the present or the future, any tense can be selected in the subordinate clause (protasis), but if a main verb (apodosis) is used in a tense of the past, an imperfecto , a pretérito perfecto , must be used or a pretérito pluscuamperfecto de subjuntivo can be placed in the protasis.

If the action of the main clause (apodosis) is in a present tense, this means that the action in the subordinate clause (protass) could have taken place before and no longer has any relation to the present. - example:

Supongo que los miembros se alegran de que tú mantuvieras. Ich vermute, dass die Mitglieder sich freuen wovon du hättest dich unterhalten. Presente de indicativo + Pretérito imperfecto de subjuntivo

So if the verb in the main clause is in a tense of the past or in the condicional simple , this means that the action or the possible occurrence in the subjunctive (protasis) could have taken place simultaneously or later than the action in the main clause. - example:

Sin embargo necesitaríamos alguna voluntaria que ayudara para el estudio de investigación. Nichtsdestotrotz würden wir brauchen eine Freiwillige die uns geholfen hätte für die Forschungsstudie. Condicional simple + Pretérito imperfecto de subjuntivo

Therefore the subjuntivo is often, but not necessarily:

- to express wishes (usually introduced by que or ojalá ):

¡Que se divierta! Viel Vergnügen! ¡Ojalá apruebes el examen! Hoffentlich bestehest du die Prüfung!

If the modal adverb ojalá is used to express a wish, the question arises whether the wish is possible or at least not improbable. If this is given, the presente de subjuntivo follows ojalá . The event time E lies in the future. - Examples:

Espero aprobar el examen de pasado mañana, he estudiado mucho. Ich erwarte zu bestehen das Examen übermorgen, ich habe studiert sehr viel. Ojalá apruebe el examen. Vielleicht bestehe ich das Examen.

If one uses ojalá with the intention of giving expression to a wish fulfillment that is either not considered possible or rather improbable, it is followed by the pretérito imperfecto de subjuntivo . - Examples:

Qué pena no poder hablar con este extraterrestre. Wie schade nicht zu sprechen können mit dem Außerirdischen. Ojalá pudiera hablar con este extraterrestre. Vielleicht könnte ich sprechen mit dem Außerirdischen.

The event time E lies in the present. If ojalá is used to express a wish that can no longer be fulfilled because it was in the past, the pretérito pluscuamperfecto de subjuntivo is used . - example:

¡Ojalá lo hubiera sabido antes! Vielleicht es ich hätte gewusst früher! Hätte ich es doch früher gewusst!

The event time E lies in the past.

Juana no llegaba. Ojalá no le hubiera pasado nada. Juana nicht kam. Hoffentlich nicht ihr wäre passiert nichts.

The subjunctive can be seen as a mode of interpretation; it rather describes the temporal relationships and so to a certain extent the "times" of the subjunctive merge past, present and future. For the concrete example it is shown; because although the event time E lies in the past, it cannot be determined exactly and the time frame of “hubiera pasado nada” is correspondingly wide.

- to express an expression of will :

- There are a number of verbs that can trigger the subjuntivo, such as aconsejar a alguien (advise someone) , esperar (hope) , insistir en algo (insist on something) , perdonar (forgive) , recomendar (recommend) , exigir (demand; demand) et cetera.

Espero que todo te vaya bien. Ich hoffe, dass alles für dich es gehe gut. Te recomendamos que vayas al colegio regularmente. Wir empfehlen dir, dass du regelmäßig zur Schule gehest / regelmäßig zur Schule zu gehen. Exijo que me digas la verdad. Ich verlange, dass du mir sagest die Wahrheit.

- In addition, there are a number of impersonal expressions , expresiones impersonales , which require the use of the subjuntivo, for example es aconsejable (que) (it is advisable) , es fundamental (que) (it is fundamental / essential) , es mejor ( que) (it's better) and so on. According to these expressions, the subjuntivo is used when there is a personal subject, after the impersonal subject there is the infinitive of the verb:

Es aconsejable que estudiéis la lengua. Es ist ratsam, dass ihr studieret die Sprache.

- The second possibility with an impersonal subject looks like this:

Es aconsejable estudiar la lengua. Es ist ratsam, die Sprache zu studieren. (Infinitiv)

- to express a subjective evaluation :

- The facts mentioned by the speaker are assumed to be true by himself . This group also contains verbs ( alegrarse , estar contento , lamentar and so on) as well as impersonal expressions such as es bueno (que) , es agradable (que) , me gusta (que) , es lógico (que) , which entail the subjunctive.

- Examples with verbs:

Me alegro de que hayáis aprobado el examen. Ich freue mich, dass ihr die Prüfung bestanden habet. Me enfada que la fiesta no tenga lugar en mi casa. Es ärgert mich, dass die Feier nicht bei mir zu Hause stattfinde.

- Example with impersonal expressions , expresiones impersonales:

Me molesta que estés tan ruidoso. Es stört mich, dass du so laut seist. Es lógico que no haya encontrado un puesto de trabajo. Es ist logisch, dass er keine Arbeitsstelle gefunden habe.

- to express the doubt , the uncertainty or the probability :

- This includes not only expressions like es probable (it is likely) or the verb dudar (to doubt) , but also the negative forms of expressions that reflect certainty.

Dudo que los profesores siempre tengan razón. Ich bezweifle, dass die Lehrer immer recht haben. Es probable que yo venga. Ich werde wahrscheinlich kommen; bzw. Ich komme wahrscheinlich. No es cierto que Pedro vaya a comprarse un coche. Es ist nicht sicher, dass sich Pedro ein Auto kaufte.

- But indicative:

Es cierto que Pedro va a comprarse un coche. Es ist sicher, dass sich Pedro ein Auto kaufen wird.

- according to negative sentences of the expression of opinion :

No creo que mañana llueva. Ich glaube nicht, dass es morgen regnet. No es verdad que todos los estudiantes sean vagos. Es stimmt nicht, dass die Studenten faul seien.

- It depends on whether the sentence that introduces the subjunctive is negated or not:

Creo que mañana no llueve. Ich glaube, dass es morgen nicht regnet. (Indikativ) Es verdad que los estudiantes no son vagos. Es stimmt, dass die Studenten nicht faul sind. (Indikativ)

- after certain conjunctions :

- These require the subjunctive, such as:

- antes (de) que - before

- para que , a fin (de) que , con el fin de que - with it

- sin que - without that

- aun cuando - even if

- después de que - after

- But some conjunctions allow the use of both the subjunctive and the indicative:

- cuando - as soon as, as, always, when

- aunque - even if, although, nevertheless, although

- por mucho que - even if, though, even if

- mientras (que) - as long as while

- si - if, if, whether

- These require the subjunctive, such as:

- in relative clause ,

- if this expresses a requirement or a condition:

Necesitamos una oficiala que tenga conocimientos en informática. Wir brauchen eine Sekretärin, die Computerkenntnisse hat.

- if the antecedent is negative and what has been said does not apply to anyone or anything:

No hay nadie que lo sepa. Es gibt niemanden, der/die es weiß.

- if the nominal group is indefinite:

Él que haya trabajado mucho, está gratificado. Derjenige der viel gearbeitet habe, wird belohnt.

- after the indefinite pronouns quienquiera (whoever) , cualquiera (any) , cualquier + noun (any) and comoquiera (whatever):

Quienquiera lo haya dicho, no me interesa. Wer es auch immer gesagt hat, es interessiert mich nicht.

- after the negative indefinite pronouns nada , nadie , ninguno or with positive indefinite pronouns such as algo or alguien

- in fixed phrases such as:

Como tú digas …. Wie du meintest, … Que yo sepa … Soviel ich weiß, …

Verbs that are close to the subjunctive (selection):

- agradar - fallen

- detestar - hate

- disgustar - displeased

- dudar - to doubt

- encantar - inspire, delight

- esperar - wait

- desear - wish, desire

- gustar - please

- molestar - disturb

- querer - like

- sorprender - astonish

- sufrir - suffer

Impersonal expressions

- The construction “impersonal expression”, expresión impersonal , + “que” often triggers the subjuntivo . These are sentences that in German regularly begin with "Es ist". There are constructions with " ser " + "noun" + "que", " ser " + "adjective" + "que" and " estar " + adverb + "que". Here are a few examples.

- es aconsejable (que) - it is advisable

- it fundamental (que) - it is fundamental, it is essential

- es importante (que) - it is important

- it probable (que) - it is probable

Sequence of times

Two linguistic statements can be related to each other in terms of time and aspect. Either one action or event precedes another, or both proceed at the same time. This chronology of events is called a sequence of times, correspondencia de tiempos, and a distinction is made between prematurity, simultaneity and post-temporality. The speaker considers whether the action, the event in the subordinate clause (protasis) compared to that of the main clause (apodosis) - played, happens or will happen earlier, at the same time or later.

The tense describes, based on the speaking time S, at which moment of the event time E the verb is performed, i.e. H. the “time” of a sentence is not related to the time of another sentence, but is freely set by the speaker or writer; either before, after or now. There are three time levels: presence, presente , past pasado and futurity futuro .

The “time” can also be viewed by the speaker or writer as dependent on or related to another entity , i. H. the “time” of one sentence, usually of a subordinate clause (protasis), is related to the “time” of another sentence, usually of the superordinate main clause (apodosis). A distinction is made here between the following time relationships (or also in the sense of Koschmieder's reference to the direction of time ): Post temporality , posterioridad , simultaneity, simultaneidad and prematurity, anterioridad . For the use of the subjuntivo, the tenses (time levels) can be divided into a present and a past group.

The aspect is a grammatical category that expresses the “internal time” of an event or a state; it does not consider the time levels, but the temporal structure of actions. It describes the inner temporal contouring of an action, an event from the speaker's perspective. The decisive factor here is the extent of an action, whether it is completed (aspecto perfectivo) or still ongoing (aspecto imperfectivo) and how the speaker or writer is involved in it. - example:

Cuando hayas cumplido treinta años te felicitaré. Wenn du habest erfüllt dreißig Jahre dir ich werde gratulieren. Pretérito perfecto de subjuntivo + Futuro simple de indicativo Aspecto imperfectivo

La joven negaba que tuviera otro novio. Die junge Frau wollte noch nicht zugeben, dass sie habe noch einen anderen Freund. Pretérito imperfecto + Pretérito imperfecto de subjuntivo (oración completiva) Die Nichtabgeschlossenheit eines Geschehens lässt sich mit dem Adverb „noch“ wiedergeben; als Ausdruck der „Imperfektivität“ übersetzen.

From the perspective of the time stages according to Hans Reichenbach (1947) or the time interval reference point R point of reference , punto de referencia, a distinction is made between three time stages : present, presente , past, pasado and future, futuro . Furthermore, the following temporal relationships are distinguished: postponement, posterioridad , simultaneity , simultaneidad and prematurity , anterioridad .

In the last example, the two linguistic statements, that of the main clause (Apodosis) “la joven negaba” and the subordinate clause (Protasis, complete clause) “tuviera otro novio” are related to each other in terms of time and aspect. Both are formed into a complete clause, oración completiva , using the relative pronoun “que” . The tense or the event E of the main clause, here in the Pretérito imperfecto de indicativo generally describes, starting from the speaking time S , at which moment of the event time E the verb is performed. The event E “la joven negaba” occurs before the speaking time S ; the reference time R refers to or discriminates through the tense of imperfecto a temporality, posterioridad , although the reference time R remains in the event time E. For the imperfecto is that the event “la joven negaba” was not concluded in the past or that the end in the past remains indefinite.

In this case, if the verb in the main clause “negaba” comes from the past group, the Pretérito imperfecto de subjuntivo is used in an attached “que” clause to express postponement . Subsequentness means that the action that is described in a subordinate construction, "tuviera otro novio", would take place after the action described in the superordinate construction "la joven negaba".

| Clause 1 | Clause 2 |

|---|---|

| Protasis | Apodosis |

| subordinate clause | main clause |

| Oración subordinada | Oración principal |

| Antecedents | Consistently |

| "Antecedent" | "Subsequent or subsequent sentence" |

| conditions | Happening, events |

| Requirements , reasons | consequences |

| Independently | Dependent |

| "Tension-creating antecedent" | "Tension-releasing addendum" |

| coordination | Subordination |

| Imagination , mental space | statement |

Aunque hayas estudiado mucho, no has aprobado ninguna asignatura. Selbst wenn du habest gelernt viel, nicht du hast bestanden niemals das Fach. Pretérito perfecto de subjuntivo + Pretérito perfecto de indicativo Aspecto perfectivo

For the present group are present, Presente , future Futuro simple o perfecto , and Perfect Pretérito perfecto , while the past group of imperfect Pretérito imperfecto , Indefinido, Pretérito indefinido , pluperfect, Pretérito pluscuamperfecto , and the conditional, Condicional simple o perfecto composed, (see also Consecutio temporum ) .

Present group:

- If the verb in the main clause belongs to the present group, the present subjuntive is used to express simultaneity. - Examples:

Me molesta que fumes. Es stört mich, dass du rauchst.

- The subjunctive perfect is used to represent prematurity:

Es lógico que no hayan aprobado el examen. Es ist logisch, dass sie die Prüfung nicht bestanden haben.

Past group:

- If the verb in the main clause is from the past group, then the imperfect of the subjuntivo is used in the attached que clause to express simultaneity and posteriority. - Examples:

Me molestó que fumaras / fumases. Es störte mich, dass du rauchen würdest.

- Prematurity is expressed by the past perfect of the subjunctive:

Fue lógico que no hubieran / hubiesen aprobado el examen. Es war logisch, dass sie die Prüfung nicht bestanden hätte.

|

Examples of the subjunctive

The first person, the speaker or the first subject of the resulting sentence expresses itself in the pronounced ( main ) sentence in such a way that it e.g. B. with the first predicate or verb describes a state of the non-real, hypothetical, uncertain, unreal. The speaker therefore “wishes”, “recommends”, “thinks”, “wants”, “suspects”, “thinks” etc. that the second person, the addressee , the second subject in the spoken ( secondary ) sentence through the connection through a conjunction or an adverb could induce that person to act accordingly. The necessary second predicate or verb of this possible action in the spoken sentence is then in the subjuntivo . - Examples:

Yo + quiero + que + hables + español. Su1 + Pr1 + Konjunktion/Adverb + Su2 + Pr2. Ich möchte, dass du Spanisch sprichst. ¿Quieres + que + te lave + el coche? Möchtest du, dass er dir das Auto wäscht?

The Spanish subjuntivo has a number of similarities with the French subjonctif , the Italian congiuntivo and the Portuguese subjuntivo . Apart from the French and Romanian subjunctive / subjunctive, it can be recognized in all other Romance languages by the alternation of the reference vowel of the respective verb conjugation.

According to Helmut Berschin , Julio Fernández-Sevilla and Josef Felixberger, the indicative is characterized as a linguistic fact of a “valid” statement, whereas a subjective statement by the speaker restricts the “validity objectively and / or subjectively”. - Examples:

Indikativ: Llega mañana. Er kommt morgen. Aussage gültig.

Subjunktiv: Tal vez llegue mañana. Vielleicht kommt er morgen. Aussage mit eingeschränkter Gültigkeit.

In the normative Spanish grammar , gramática normativa , the indicative , modo indicativo , gives expression to “objectivity” or “reality”. For the modo subjuntivo, on the other hand, a subjective attitude of the speaker or the possibilities are expressed. So:

- A speaker establishes and reports, i.e. passes on the message, the statement content "unchanged": indicative.

- A spokesman interprets and gives the message or the message content on the condition of desire ( opt ), anticipation, uncertainty, hesitation, doubt, joy, etc. recommendation continues: subjunctive.

A hypothetical view or representation of the subjunctive, which is not undisputed (see under “ 4. General ”). Because according to another assumption on this topic, the subjunctive and the indicative would each show themselves as one of two basic functions of the Spanish language and, as presentation figures, promise certain events.

Examples (in the translation of the 3rd and 5th sentences the subjunctive stylistically "wrong" reproduced):

| Subjuntivo Pretérito Presente: | Aunque llueva , iré a verte. | Present subjunctive : | Even if it rains I will visit you. |

| Indicativo Presente: | Aunque llueve , iré a verte. | Indicative present tense: | Even though it's raining , I'll visit you. |

| Subjuntivo Pretérito Presente: | Es fácil que llueva . | Present subjunctive : | It is likely that it was raining (correct: raining , could rain, etc.). |

| Indicativo Pretérito Presente: | Creo que llueve hoy. | Indicative present tense: | I think it's raining today . |

| Subjuntivo Pretérito Presente: | No creo que llueva hoy. | Present subjunctive : | I don't think it rained today (correct: it will rain , rain is coming, etc.). |

Overview table of endings for regular verbs . A comparison of the modes:

| Modo indicativo | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Presente | Pretérito perfecto simple | Pretérito imperfecto | Futuro simple | Conditional simple | |||||||||||||||||

| I. | II. | III. | I. | II. | III. | I. | II. | III. | I. | II. | III. | I. | II. | III. | |||||||

| -O | -O | -O | -é | -í | -í | -aba | -ía | -ía | -aré | -eré | -Irishman | -aría | -ería | -iría | |||||||

| -as | -ás | -it | -it | -it | -ís | -aste | -ist | -ist * | -abas | -ías | -ías | -arás | -erás | -irás | -arías | -erías | -irías | ||||

| -a | -e | -e | -O | -ió | -ió | -aba | -ía | -ía | -era | -erá | -irá | -aría | -ería | -iría | |||||||

| -amos | -emos | -imos | -amos | -imos | -imos | -abamos | -íamos | -íamos | -aremos | -eremos | -iremos | -aríamos | -eríamos | -iríamos | |||||||

| -áis | -ice | -ís | -asteis | -isteis | -isteis | -abais | -íais | -íais | -aréis | -eréis | -iréis | -aríais | -eríais | -iríais | |||||||

| -on | -en | -en | -aron | -ieron | -ieron | -aban | -ían | -ían | -arán | -erán | -Iran | -arían | -erían | -irían | |||||||

| Modo subjuntivo | Modo imperativo | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Presente | Pretérito imperfecto I. | Pretérito imperfecto II | Futuro simple | Imperativo positivo | |||||||||||||||||

| I. | II. | III. | I. | II. | III. | I. | II. | III. | I. | II. | III. | I. | II. | III. | |||||||

| -e | -a | -a | -era | -iera | -iera | -ase | -these | -these | -are | -iere | -iere | - | - | - | |||||||

| -it | -as | -as | -aras | -ieras | -ieras | -ases | -this | -this | -ares | -ieres | -ieres | -a | -á | -e | -é | -e | -í | ||||

| -e | -a | -a | -era | -iera | -iera | -ase | -these | -these | -are | -iere | -iere | -e | -a | -a | |||||||

| -emos | -amos | -amos | -áramos | -iéramos | -iéramos | -ásemos | -iésemos | -iésemos | -áremos | -iéremos | -iéremos | -emos | -amos | -amos | |||||||

| -ice | -áis | -áis | -arais | -ierais | -ierais | - ice cream | - ice cream | - ice cream | -areis | - ice cream | - ice cream | -ad | -ed | -id | |||||||

| -en | -on | -on | -aran | -ier on | -ier on | -asen | -this | -this | -aren | -ieren | -ieren | -en | -on | -on | |||||||

| Formas no personales | * Forms in -astes and -istes have been condemned by academic institutions, but are used in everyday language in informal situations. | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Infinitivo | Participio | Gerundio | |||||||||||||||||||

| I. | II. | III. | I. | II. | III. | I. | II. | III. | |||||||||||||

| -ar | -he | -ir | -ado / a (-ante) |

-ido / a (-iente) |

-ido / a (-iente) |

-ando | -iendo | -iendo | |||||||||||||

In the sentences that are in the subjunctive / subjunctive, the speaker can not only verbalize a remembered fact, but at the same time pass on further information ( modalities ) about his assumptions to his interlocutor . In principle, the speaker uses the subjunctive / conjunctive in order to modulate his statement in relation to the remembered reality in such a way that the content is given a subjective validity. In addition to the possible factual statement in the indicative / indicative, the speaker can communicate his expectations , assessments, wishes, fears , etc. in the verbal issue. Moreover, the fact that the facts and modalities communicated by the sentence in question are not true in the remembered reality enables the speaker to create another alternative reality in the communication.

All tenses , tiempos gramaticales , for the verb genders or genera verbi, so the active (activity form), voz activa , can also be set in the passive (suffering form), voz pasiva . Certain peculiarities for the passive voice have to be taken into account for the Spanish language . The Spanish passive voice, voz pasiva , in the broadest sense, is sometimes used differently than in the German language , depending on its direction of action or diathesis .

Correct use of grammatical rules

In Spanish, the subjuntivo would (according to one hypothesis) find its use when expressing wishes , doubts , hope , joy , anger , non-reality, insecurity , influence, etc. In other words, it is necessary in a conversation about his opinions to express his feeling or perceptions promised union and facts presented as possible. In principle, German also lists this possibility by using the subjunctive II to express the impossible or the unreal. In Spanish, the verbalizations of feeling perceptions or feeling-related statements are grammatically of limited validity. In German, however, this is not the case. - Examples:

Tal vez viene a visitarnos. Vielleicht kommt er uns besuchen. Wahrscheinliche Erwartung, deshalb Indicativo. Tal vez venga a visitarnos. Vielleicht kommt er (mal) uns besuchen. Eher unwahrscheinliche Erwartung, deshalb Subjuntivo.

Some phrases or phrases can be used to express what is the case, then use the indicativo , or as an expression of what should be the case, then use the subjuntivo . - Examples:

El caso es que no te ven. Tatsache ist, dass nicht dich sie sehen. El caso es que no te vean. Die Sache ist folgendermaßen, dass nicht dich sehen. Se trata de que la vida es eterna. Es geht darum, dass das Leben ewig ist. Se trata de que la vida sea eterna. Es geht darum, dass das Leben ewig sei.

In general, the German subjunctive and the Spanish subjunctive are not used in the same way for all linguistic expressions of the various contextual facts. Example: He says she is coming (German Konjunktiv II), but in Spanish Dice que viene . (Indicative). Conversely, there are sentence constructions in which the indicative is used in German and the subjunctive in Spanish, as well as an intersection of matching modes in both languages. However, to a certain extent the assignment requirements for the two modes are clearly different in the two languages.

While Spanish now chooses stable forms with regard to its requirements and the resulting consequences, German has a completely incoherent system for similar requirements. Although a similar step could be taken with the subjunctive II as in Spanish, the German language, especially in colloquial language, deviates into a wide variety of grammatical forms. In relation to the subjunctive II, German is an unstable system insofar as the speakers of their mother tongue can or do employ completely different grammatical constructs in their speech - with regard to the above-mentioned requirements.

"The subjunctive II serves here [functional area 1 'unreality / potentiality'] as a sign that the speaker / writer does not want his statement to be understood as a statement about the real, but as a conceptual construction."

In Romance languages, such as Spanish, Italian and French, a clear distinction is made between the subjunctive and the conditional . In contrast to this, in German the subjunctive is increasingly being assimilated to the conditional. This is also the reason why the modal verbs in the Romance languages are far less grammaticalized.

| The German subjunctive I + II | The Spanish subjunctive |

|---|---|

| Present | Presente de subjuntivo |

| Future tense I. | Futuro simple de subjuntivo |

| Subjunctive II present tense | Pretérito imperfecto de subjuntivo |

| Subjunctive I past tense | Pretérito perfecto de subjuntivo |

| Subjunctive II past tense | Pretérito pluscuamperfecto de subjuntivo |

| Future tense II | Future perfecto de subjuntivo |

Conjugations the example of rain / llover:

| The German subjunctive I + II | The Spanish subjunctive |

|---|---|

| Present tense it's raining | Presente llueva |

| Future I it would rain | Futuro lloviere |

| Present subjunctive it was raining | Pretérito imperfecto lloviera |

| Subjunctive I simple past rained | Pretérito perfecto haya llovido |

| Subjunctive second past tense would have rained | Pretérito pluscuamperfecto hubiera llovido |

| Future II it would have rained | Futuro perfecto hubiere llovido |

Formation of the Spanish Subjuntivo

As in other modes in Spanish, you have to distinguish between the verbs that end in -ar or -er and -ir in the subjunctive . When forming the Subjuntivo de presente, the first person singular indicative serves as the basis. During conjugation, the characteristic personal endings are exchanged. Thus the verbs ending in -ar get an -e and the verbs ending -er and -ir get an -a as an ending. The formation of the Spanish subjuntivo is therefore approximately the same as the formation of the present subjunctive in Latin, from which it developed. Furthermore, the forms of the subjuntivo are identical to the forms of the negated imperative , Imperativo negativo .

The subjuntivo can be formed for all times, with the exception of the pretérito indefinido and the pretérito anterior .

Present tense (presente de subjuntivo)

If the verb is in the main clause (apodosis) in the tenses presente , pretérito perfecto , futuro simple or in the imperative mode , modo imperativo , the presente de subjuntivo is used for the subordinate clause (protasis) .

Example: The verb in the main clause alegrar is in the presente and the verb venir in the subordinate clause in the presente de subjuntivo:

Me alegro de que vengas a verme. Ich freue mich, dass du mich besuchen kommest. Presente de indicativo + Presente de subjuntivo

Regular verbs

In verbs on -ar end, are in the subjunctive present tense following endings to the root word (or word root ) attached:

| person | Ending |

|---|---|

| yo | -e |

| tú | -it |

| usted, él, ella | -e |

| nosotros / -as | -emos |

| vosotros / -as | -ice |

| ustedes, ellos, ellas | -en |

Verbs ending in -er and -ir get these endings in the subjunctive:

| person | Ending |

|---|---|

| yo | -a |

| tú | -as |

| usted, él, ella | -a |

| nosotros / -as | -amos |

| vosotros / -as | -áis |

| ustedes, ellos, ellas | -on |

Example of the regular verbs tomar , comer and vivir:

| person | Subjuntivo present tense (Presente de subjuntivo) | Formal German translation (conjunctivus praesentis) (subjunctive I present active) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| tomar | yo | tome | drink |

| tú | tomes | drink | |

| usted, él, ella | tome | drink | |

| nosotros / -as | tomemos | drink | |

| vosotros / -as | toméis | drink | |

| ustedes, ellos, ellas | tomen | drink |

| person | Subjuntivo present tense (Presente de subjuntivo) | Formal German translation (conjunctivus praesentis) (subjunctive I present active) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| comer | yo | coma | eat |

| tú | comas | eat | |

| usted, él, ella | coma | eat | |

| nosotros / -as | comamos | eat | |

| vosotros / -as | comáis | eats | |

| ustedes, ellos, ellas | coman | eat |

| person | Subjuntivo present tense (Presente de subjuntivo) | Formal German translation (conjunctivus praesentis) (subjunctive I present active) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| vivir | yo | viva | live |

| tú | vivas | live | |

| usted, él, ella | viva | live | |

| nosotros / -as | vivamos | dwell | |

| vosotros / -as | viváis | resides | |

| ustedes, ellos, ellas | vivan | dwell |

Irregular verbs

In addition to the regular verbs used above, there are a large number of irregular verbs in Spanish, or verbs in which a certain person is irregular. The three verbs estar , saber and ir serve as an example :

| person | Subjuntivo present tense (Presente de subjuntivo) | Formal German translation (conjunctivus praesentis) (subjunctive I present active) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| estar | yo | esté | be |

| tú | estés | be | |

| usted, él, ella | esté | be | |

| nosotros / -as | estemos | be | |

| vosotros / -as | estéis | be | |

| ustedes, ellos, ellas | estén | be |

| person | Subjuntivo present tense (Presente de subjuntivo) | Formal German translation (conjunctivus praesentis) (subjunctive I present active) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| drool | yo | sepa | know |

| tú | sepas | know | |

| usted, él, ella | sepa | know | |

| nosotros / -as | sepamos | knowledge | |

| vosotros / -as | sepáis | know | |

| ustedes, ellos, ellas | sepan | knowledge |

| person | Subjuntivo present tense (Presente de subjuntivo) | Formal German translation (conjunctivus praesentis) (subjunctive I present active) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ir | yo | vaya | go |

| tú | vayas | go | |

| usted, él, ella | vaya | go | |

| nosotros / -as | vayamos | go | |

| vosotros / -as | vayáis | go | |

| ustedes, ellos, ellas | vayan | go |

The presente de subjuntivo in the process passive , pasiva de proceso , denotes a process and is conjugated with the copula verb .

| person | Process passive subjuntivo present tense (presente de subjuntivo, pasiva de proceso) | Formal German translation (subjunctive I present passive) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| tomar | yo | sea tomado | be drunk |

| tú | seas tomado | be drunk | |

| usted, él, ella | sea tomado | be drunk | |

| nosotros / -as | seamos tomado | be drunk | |

| vosotros / -as | seáis tomado | be drunk | |

| ustedes, ellos, ellas | sean tomado | be drunk |

| person | Process passive subjuntivo present tense (presente de subjuntivo, pasiva de proceso) | Formal German translation (subjunctive I present passive) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| comer | yo | sea comido | be eaten |

| tú | seas comido | be eaten | |

| usted, él, ella | sea comido | be eaten | |

| nosotros / -as | seamos comido | be eaten | |

| vosotros / -as | seáis comido | be eaten | |

| ustedes, ellos, ellas | sean comido | be eaten |

| person | Process passive subjuntivo present tense (presente de subjuntivo, pasiva de proceso) | Formal German translation (subjunctive I present passive) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| vivir | yo | sea vivido | be used to |

| tú | seas vivido | be used to | |

| usted, él, ella | sea vivido | be used to | |

| nosotros / -as | seamos vivido | are used to | |

| vosotros / -as | seáis vivido | be used to | |

| ustedes, ellos, ellas | sean vivido | are used to |

Perfect (Pretérito perfecto de subjuntivo)

The pretérito perfecto de subjuntivo is formed from the subjuntivo present of the verb haber and the past participle, participio perfecto , of the corresponding verb. The forms of the regular verbs from the example above then look like this:

| person | Subjuntivo Perfect (Perfecto de subjuntivo) | Formal German translation (subjunctive I perfect active) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| tomar | yo | haya tomado | have been drinking |

| tú | hayas tomado | have been drinking | |

| usted, él, ella | haya tomado | have been drinking | |

| nosotros / -as | hayamos tomado | have drunk | |

| vosotros / -as | hayáis tomado | have been drinking | |

| ustedes, ellos, ellas | hayan tomado | have drunk |

| person | Subjuntivo Perfect (Perfecto de subjuntivo) | Formal German translation (subjunctive I perfect active) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| comer | yo | haya comido | have eaten |

| tú | hayas comido | have eaten | |

| usted, él, ella | haya comido | have eaten | |

| nosotros / -as | hayamos comido | have eaten | |

| vosotros / -as | hayáis comido | ate | |

| ustedes, ellos, ellas | hayan comido | have eaten |

| person | Subjuntivo Perfect (Perfecto de subjuntivo) | Formal German translation (subjunctive I perfect active) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| vivir | yo | haya vivido | lived |

| tú | hayas vivido | lived | |

| usted, él, ella | haya vivido | lived | |

| nosotros / -as | hayamos vivido | have lived | |

| vosotros / -as | hayáis vivido | lived | |

| ustedes, ellos, ellas | hayan vivido | have lived |

The pretérito perfecto de subjuntivo in the process passive, pasiva de proceso , is conjugated with the copula verb .

| person | Process passive Subjuntivo Pretérito perfecto (Pretérito perfecto de subjuntivo, pasiva de proceso) | Formal German translation (subjunctive I perfect passive) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| tomar | yo | haya sido tomado | had been drunk |

| tú | hayas sido tomado | had been drunk | |

| usted, él, ella | haya sido tomado | had been drunk | |

| nosotros / -as | hayamos sido tomado | had been drunk | |

| vosotros / -as | hayáis sido tomado | had been drunk | |

| ustedes, ellos, ellas | hayan sido tomado | had been drunk |

| person | Process passive Subjuntivo Pretérito perfecto (Pretérito perfecto de subjuntivo, pasiva de proceso) | Formal German translation (subjunctive I perfect passive) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| comer | yo | haya sido comido | had been eaten |

| tú | hayas sido comido | have been eaten | |

| usted, él, ella | haya sido comido | had been eaten | |

| nosotros / -as | hayamos sido comido | had been eaten | |

| vosotros / -as | hayáis sido comido | had been eaten | |

| ustedes, ellos, ellas | hayan sido comido | had been eaten |

| person | Process passive Subjuntivo Pretérito perfecto (Pretérito perfecto de subjuntivo, pasiva de proceso) | Formal German translation (subjunctive I perfect passive) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| vivir | yo | haya sido vivido | had been used |

| tú | hayas sido vivido | have been lived | |

| usted, él, ella | haya sido vivido | had been used | |

| nosotros / -as | hayamos sido vivido | had been used | |

| vosotros / -as | hayáis sido s vivido | had been lived | |

| ustedes, ellos, ellas | hayan sido vivido | had been used |

Imperfect tense (imperfecto de subjuntivo)

Regular verbs

The imperfect of the subjuntivo, Pretérito imperfecto de subjuntivo, is derived from the third person plural of the indefinido of the verb. The ending -aron then with verbs in -ar by -ara or -ase , with verbs in -er and -ir the -ieron by -iera or -iese replaced. The two forms are basically equivalent. Usually the region is decisive for the use of one or the other ending. However, the form -ra cannot be replaced by -se if the former can be replaced by past perfect or conditional. This is due to historical reasons, as the -ra -form arose from the Latin past perfect indicative, while its alternative is based on the Latin past perfect subjunctive.

| person | Subjuntivo imperfect (Imperfecto de subjuntivo) | Formal German translation ( subjunctive II past tense active) (or would plus infinitive present tense ) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| tomar | yo | tomara / tomase | beverage (or would drink) |

| tú | tomaras / tomases | soak | |

| usted, él, ella | tomara / tomase | potions | |

| nosotros / -as | tomáramos / tomásemos | soak | |

| vosotros / -as | tomarais / tomaseis | soaks | |

| ustedes, ellos, ellas | tomaran / tomasen | soak |

| person | Subjuntivo imperfect (Imperfecto de subjuntivo) | Formal German translation (subjunctive II past tense active) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| comer | yo | comiera / comiese | eat |

| tú | comieras / comieses | äßest | |

| usted, él, ella | comiera / comiese | eat | |

| nosotros / -as | comiéramos / comiésemos | ate | |

| vosotros / -as | comierais / comieseis | eats | |

| ustedes, ellos, ellas | comieran / comiesen | ate |

| person | Subjuntivo imperfect (Imperfecto de subjuntivo) | Formal German translation (subjunctive II past tense active) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| vivir | yo | viviera / viviese | lived |

| tú | vivieras / vivieses | you lived | |

| usted, él, ella | viviera / viviese | lived | |

| nosotros / -as | viviéramos / viviésemos | lived | |

| vosotros / -as | vivierais / vivieseis | lived | |

| ustedes, ellos, ellas | vivieran / viviesen | lived |

Irregular verbs

| person | Subjuntivo imperfect (Imperfecto de subjuntivo) | Formal German translation (subjunctive II past tense active) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| estar | yo | estuviera / estuviese | would |

| tú | estuvieras / estuvieses | would be | |

| usted, él, ella | estuviera / estuviese | would | |

| nosotros / -as | estuviéramos / estuviésemos | would be | |

| vosotros / -as | estuvierais / estuvieseis | would be | |

| ustedes, ellos, ellas | estuvieran / estuviesen | would be |

| person | Subjuntivo imperfect (Imperfecto de subjuntivo) | Formal German translation (subjunctive II past tense active) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| drool | yo | supiera / supiese | know |

| tú | supieras / supieses | would know | |

| usted, él, ella | supiera / supiese | know | |

| nosotros / -as | supiéramos / supiésemos | would know | |

| vosotros / -as | supierais / supieseis | know | |

| ustedes, ellos, ellas | supieran / supiesen | would know |

| person | Subjuntivo imperfect (Imperfecto de subjuntivo) | Formal German translation (subjunctive II past tense active) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ir | yo | füra / fuese | would go |

| tú | füras / fueses | went | |

| usted, él, ella | füra / fuese | would go | |

| nosotros / -as | fuéramos / fuésemos | went | |

| vosotros / -as | fuerais / fueseis | went | |

| ustedes, ellos, ellas | foran / fuesen | went |

The decisive factor for the use of the past tense of the subjuntivo is the form of the expression that triggers the subjuntivo (see again use of the subjuntivo ). Is the verb of the main clause in the indefinido , imperfecto or in the condicional and should wishes, feelings, recommendations, non-realities, doubts, rejections, etc. Ä. m. are expressed, the past tense of the subjunctive must be used. Even if the speaker wants to express an unreal comparison with como si (German: as if ), the subjuntivo is used.

| Clause 1 | Clause 2 |

|---|---|

| Protasis | Apodosis |

| subordinate clause | main clause |

| Oración subordinada | Oración principal |

| Antecedents | Consistently |

| "Antecedent" | "Subsequent or subsequent sentence" |

| Temporal and aspect-related determination of the main clause | Happening of the main clause time, space |

| Independently | Dependent |

| coordination | Subordination |

One forms the form:

- Indefinido / Imperfecto / Condicional (indicative, main clause (apodosis) ) + Pretérito imperfecto del subjuntivo ( subordinate clause )

For the pretérito imperfecto del subjuntivo in the process passive , pasiva de proceso o pasiva con ser , the copula verb ser is conjugated.

| person | Process passive subjuntivo imperfect (Imperfecto de subjuntivo, pasiva de proceso) | Formal German translation (subjunctive II past passive) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| tomar | yo | füra tomado | would be drunk |

| tú | for the tomado | would be drunk | |

| usted, él, ella | füra tomado | would be drunk | |

| nosotros / -as | fuéramos tomado | would be drunk | |

| vosotros / -as | fuerais tomado | would be drunk | |

| ustedes, ellos, ellas | füran tomado | would be drunk |

| person | Process passive subjuntivo imperfect (Imperfecto de subjuntivo, pasiva de proceso) | Formal German translation (subjunctive II past passive) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| comer | yo | füra comido | would be eaten |

| tú | for the comido | would be eaten | |

| usted, él, ella | füra comido | would be eaten | |

| nosotros / -as | fuéramos comido | would be eaten | |

| vosotros / -as | fuerais comido | would be eaten | |

| ustedes, ellos, ellas | furan comido | would be eaten |

| person | Process passive subjuntivo imperfect (Imperfecto de subjuntivo, pasiva de proceso) | Formal German translation (subjunctive II past passive) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| vivir | yo | füra vivido | would be used |

| tú | füras vivido | would be used to | |

| usted, él, ella | füra vivido | would be used | |

| nosotros / -as | fuéramos vivido | would be used | |

| vosotros / -as | fuerais vivido | would be used | |

| ustedes, ellos, ellas | foran vivido | would be used |

Dudábamos que viniera. Wir zweifelten, dass er käme. Pretérito imperfecto de indicativo + Pretérito imperfecto de subjuntivo Le dije que lavara la cubertería. Ihm ich sagte, dass er abwaschen sollte das Besteck. Me alegraba de que te durmieras. Ich war erfreut, dass du geschlafen hast. Compraría una autocaravana si tuviera más espacio. Er würde kaufen ein Wohnmobil, wenn er würde haben mehr Platz. condicional simple + Pretérito imperfecto de subjuntivo

Past perfect (pluscuamperfecto de subjuntivo)

Premature past tense is the past perfect tense, Pretérito pluscuamperfecto de subjuntivo . It is formed from the imperfect subjunctive, Pretérito imperfecto de subjuntivo of the auxiliary verb haber and the past participle , participio pasado o perfecto of the verb. Subjuntivo mode is used in subordinate clauses (protasis) that describe actions or events that are only to be brought about, or facts that have only arisen due to another fact . It therefore occurs in subordinate clauses (protasis). Here prematurity , anterioridad , plays an important role. If the verb is in the main clause (apodosis) in the tenses listed below, such as the Pretérito Imperfecto , Pretérito Indefinido , Pretérito Pluscuamperfecto indicativo or also subjuntivo or in the Condicional Perfecto and if the action sequence in the subordinate clause takes place before the action in the main clause, the pluscuamperfect becomes the pluscuam subjuntivo used. - Example: The verb in the main clause alegrar is in the Pretérito Indefinido and the verb irse in the subordinate clause is in the Pluscuamperfecto de subjuntivo:

Me alegró que mi esposa me hubiera ido a esperar al teatro. Es freute mich, dass meine Ehefrau zum Theater gefahren war, um mich abzuholen. Pretérito indefinido de indicativo + Pretérito pluscuamperfecto de subjuntivo

In other words, there is no prematurity or only a posteriority , posterioridad . The tense structure of the main clause is retained, only the mode changes from the Modo indicativo of the main clause to the Modo subjuntivo of the subordinate clause. The following applies: In the case of simultaneity, simultaneidad , in the main clause, the same tense follows as the subjuntivo in the subordinate clause.

Actions and events are therefore expressed in general , which took place before a certain point in time in the past or which could have taken place in the past under other conditions .

| person | Subjuntivo past perfect (Pluscuamperfecto de subjuntivo) | Formal German translation ( conjunctivus praesentis of "haben" plus the "past participle") (subjunctive II past perfect active) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| tomar | yo | hubiera / hubiese tomado | would have drunk |

| tú | hubieras / hubieses tomado | would have drunk | |

| usted, él, ella | hubiera / hubiese tomado | would have drunk | |

| nosotros / -as | hubiéramos / hubiésemos tomado | would have drunk | |

| vosotros / -as | hubierais / hubieseis tomado | would have drunk | |

| ustedes, ellos, ellas | hubieran / hubiesen tomado | would have drunk |

| person | Subjuntivo past perfect (Pluscuamperfecto de subjuntivo) | Formal German translation ( conjunctivus praesentis of "haben" plus the "past participle") (subjunctive II past perfect active) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| comer | yo | hubiera / hubiese comido | would have eaten |

| tú | hubieras / hubieses comido | would have eaten | |

| usted, él, ella | hubiera / hubiese comido | would have eaten | |

| nosotros / -as | hubiéramos / hubiésemos comido | would have eaten | |

| vosotros / -as | hubierais / hubieseis comido | would have eaten | |

| ustedes, ellos, ellas | hubieran / hubiesen comido | would have eaten |

| person | Subjuntivo past perfect (Pluscuamperfecto de subjuntivo) | Formal German translation ( conjunctivus praesentis of "haben" plus the "past participle") (subjunctive II past perfect active) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| vivir | yo | hubiera / hubiese vivido | would have lived |

| tú | hubieras / hubieses vivido | would have lived | |

| usted, él, ella | hubiera / hubiese vivido | would have lived | |

| nosotros / -as | hubiéramos / hubiésemos vivido | would have lived | |

| vosotros / -as | hubierais / hubieseis vivido | would have lived | |

| ustedes, ellos, ellas | hubieran / hubiesen vivido | would have lived |

The pluscuamperfecto de subjuntivo in the process passive, pasiva de proceso , characterizes an earlier process or event that was previously exposed to another action or state in the past. Here, too, the copula verb is conjugated.

| person | Process passive Subjuntivo Pretérito perfecto (Pretérito perfecto de subjuntivo, pasiva de proceso) | Formal German translation (subjunctive I perfect passive) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| tomar | yo | hubiera sido tomado | had been drunk |

| tú | hubieras sido tomado | had been drunk | |

| usted, él, ella | hubiera sido tomado | had been drunk | |

| nosotros / -as | hubiéramos sido tomado | had been drunk | |

| vosotros / -as | hubierais sido tomado | had been drunk | |

| ustedes, ellos, ellas | hubieran sido tomado | had been drunk |

| person | Process Passive Subjuntivo Plusquamperfekt (Pluscuamperfecto de subjuntivo, pasiva de proceso) | Formal German translation (subjunctive I perfect passive) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| comer | yo | hubiera sido comido | had been eaten |

| tú | hubieras sido comido | have been eaten | |

| usted, él, ella | hubiera sido comido | had been eaten | |

| nosotros / -as | hubiéramos sido comido | had been eaten | |

| vosotros / -as | hubierias sido comido | had been eaten | |

| ustedes, ellos, ellas | hubieran sido comido | had been eaten |

| person | Process Passive Subjuntivo Plusquamperfekt (Pluscuamperfecto de subjuntivo, pasiva de proceso) | Formal German translation (subjunctive I perfect passive) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| vivir | yo | hubiera sido vivido | had been used |

| tú | hubieras sido vivido | have been lived | |

| usted, él, ella | hubiera sido vivido | had been used | |

| nosotros / -as | hubiériamos sido vivido | had been used | |

| vosotros / -as | hubierais sido s vivido | had been lived | |

| ustedes, ellos, ellas | hubieran sido vivido | had been used |

Future tense (futuro de subjuntivo)

The futuro simple de subjuntivo , analogous to the imperfect subjuntivo, is formed from the third person plural of the indefinido. However, here the ending -aron in the first person is replaced by -are or -iere and conjugated from this:

| person | Subjuntivo Future (Futuro imperfecto de subjuntivo) | Formal German translation ( conjunctivus praesentis of "werden" plus the "infinitive") (subjunctive II future I active) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| tomar | yo | tomare | would drink |

| tú | tomares | would drink | |

| usted, él, ella | tomare | would drink | |

| nosotros / -as | tomáremos | would drink | |

| vosotros / -as | tomareis | would drink | |

| ustedes, ellos, ellas | tomaren | would drink |

| person | Subjuntivo Future (Futuro imperfecto de subjuntivo) | Formal German translation ( conjunctivus praesentis of "werden" plus the "infinitive") (subjunctive II future I active) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| comer | yo | comiere | would eat |

| tú | comieres | would eat | |

| usted, él, ella | comiere | would eat | |

| nosotros / -as | comiéremos | would eat | |

| vosotros / -as | comiereis | would eat | |

| ustedes, ellos, ellas | comieren | would eat |

| person | Subjuntivo Future (Futuro imperfecto de subjuntivo) | Formal German translation ( conjunctivus praesentis of "werden" plus the "infinitive") subjunctive II future I active | |

|---|---|---|---|

| vivir | yo | live | would live |

| tú | vivieres | would live | |

| usted, él, ella | live | would live | |

| nosotros / -as | viviéremos | would live | |

| vosotros / -as | live rice | would live | |

| ustedes, ellos, ellas | vivate | would live |

The future tense of the subjuntivo is only rarely used and when it is, then only in the written language. This is usually the third person who is still used, for example, in formal letters such as legal texts. - example:

El concesionario responderá de cualquier daño perjuicio que se originare por terceros. Der Lizenzträger haftet für jeden Schaden, der durch Dritte entsteht.

There are also some fixed idioms that use the future tense of the subjuntivo, but are now increasingly being replaced by forms of the present tense. - example:

Sea lo que fuere. (Heutzutage verbreiteter: Sea lo que sea.; Wie dem auch sei. Oder: Sei es, wie es wolle.)

Future perfecto ( Future perfecto de subjuntivo)

The futuro perfecto de subjuntivo is formed from the future subjuntivo of the auxiliary verb haber and the past participle of the following verb.

| person | Subjuntivo Futur perfecto (Futuro perfecto de subjuntivo) | Formal German translation ( subjunctive II future II active ) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| tomar | yo | hubiere tomado | would have been drinking |

| tú | hubieres tomado | would have been drinking | |

| usted, él, ella | hubiere tomado | would have been drinking | |

| nosotros / -as | hubiéremos tomado | would have been drinking | |

| vosotros / -as | hubiereis tomado | would have been drinking | |

| ustedes, ellos, ellas | lift tomado | would have been drinking |

| person | Subjuntivo Future (Futuro imperfecto de subjuntivo) | Formal German translation (subjunctive II future II active) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| comer | yo | hubiere comido | would have eaten |

| tú | hubieres comido | would have eaten | |

| usted, él, ella | hubiere comido | would have eaten | |

| nosotros / -as | hubiéremos comido | would have eaten | |

| vosotros / -as | hubiereis comido | would have eaten | |

| ustedes, ellos, ellas | hubing comido | would have eaten |

| person | Subjuntivo Future (Futuro imperfecto de subjuntivo) | Formal German translation (subjunctive II future II active) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| vivir | yo | hubiere vivido | would have lived |

| tú | hubieres vivido | would have lived | |

| usted, él, ella | hubiere vivido | would have lived | |

| nosotros / -as | hubiéremos vivido | would have lived | |

| vosotros / -as | hubiereis vivido | would have lived | |

| ustedes, ellos, ellas | hubieren vivido | would have lived |

Analytical passive and subjunctive

It is formed with the conjugated auxiliary verb ser or estar (German "sein" or "werden or werden sein") and the participio pasado or perfecto or pasivo of the corresponding verb. It is not absolutely necessary to name the author of the action, but if he appears, then in connection with the preposition por or more rarely with de . - Examples:

Pedro comió las peras. Pedro aß die Birnen (Aktiv); oder Las peras fueron comidas por Pedro. Die Birnen wurden von Pedro gegessen (Passiv genauer pasiva con ser).

The analytical passive, pasiva de analítica , is in turn divided into process passive and state passive .

- The process passive, pasiva con ser is used to express processes, processes and process-like events;

- The state passive, pasiva con estar , is required to express the result of an action, fact or state.

| Process passive (selection) subjuntivo | ser | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| person | Presente | Imperfecto | Perfecto | Pluscuamperfecto | Futuro | Participio pasado or perfecto |

| yo | sea (I'm being irradiated) | füra (I would be irradiated) | haya sido (I was irradiated) | hubiera sido (I would have been irradiated) | hubiere sido (i will be irradiated) | radiado |

| tú | seas | foras | hayas sido | hubieras sido | hubieres sido | radiado |

| él, ella | sea | for a | haya sido | hubiera sido | hubiere sido | radiado |

| nosotros, nosotras | seamos | fuéramos | hayamos sido | hubiéramos sido | hubiéremos sido | radiado |

| vosotros, vosotras | seáis | fürais | hayáis sido | habierais sido | hubiereis sido | radiado |

| ellos, ellas | sean | foran | hayan sido | have sido | hub sido | radiado |

| State passive (selection) subjuntivo | estar | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| person | Presente | Imperfecto | Perfecto | Pluscuamperfecto | Futuro | Participio pasado or perfecto |

| yo | esté (I am irradiated) | estuviera (I would be irradiated) | haya estado (I was irradiated) | hubiera estado (I would have been irradiated) | hubiere estado (I would be irradiated) | radiado |

| tú | estés | estuvieras | hayas estado | hubieras estado | hubieres estado | radiado |

| él, ella | esté | estuviera | haya estado | hubiera estado | hubiere estado | radiado |

| nosotros, nosotras | estemos | estuviéramos | hayamos estado | hubiéramos estado | hubiéremos estado | radiado |

| vosotros, vosotras | estéis | estestuvierais | hayáis estado | habierais estado | hubiereis estado | radiado |

| ellos, ellas | estén | estuvieran | hayan estado | have estado | hub estado | radiado |

Conjunctions and Subjunctive

In Spanish it is particularly important to ensure that some conjunctions result in the indicative, indicativo , others the subjuntivo and some also the infinitive, infinitivo .

Classification of the Spanish conjunctions

There are three parts of speech in Spanish that can function as conjunctions , they are:

- Single word conjunctions, conjunciones simples

- compound conjunctions, conjunciones compuestas , and

- Adverbs, adverbios .

They can also be classified according to their syntactic functions:

- Associating or co-ordinating conjunctions, conjunciones de coordinación , link similar clauses or sentences with one another. These are again sorted into

- Sequential conjunctions, conjunciones copulativos , which cause a sequence of the various parts of the sentence or sentences of equal rank. Example: tanto… como, ni… ni.

- Adversative conjunctions, conjunciones adversativas . They indicate an antithesis to the preceding sentence. Example: aunque, sino .

- Disjunctive conjunctions, conjunciones disyuntivas , express that there is only one possibility. Example: bien ... bien, o ... o .

- Inferential conjunctions, conjunciones conclusivas , introduce a conclusion. Example: entonces .

- Subordinate conjunctions, conjunciones de subordinación . They introduce subordinate clauses and, depending on the requirements, can result in the indicative, indicativo or subjuntivo . These conjunctions can also be arranged in individual groups, see above

- Temporal conjunctions, conjunciones temporales ,

- Final conjunctions, conjunciones finales ,

- Causal conjunctions, conjunciones causales , example: que, ya que, puesto que, porque

- Consecutive conjunctions, conjunciones consecutivas ,

- Concessive conjunctions, conjunciones concesivas ,

- Conditional conjunctions, conjunciones condicionales ,

- Adversative conjunctions, conjunciones adversitivas ,

- Stringing conjunctions, conjunciones copulativas ,

- Modal conjunctions, conjunciones modales .

Linguistic history on the Romance subjunctive in general and the Spanish subjunctive in particular

It is assumed that five modes were distinguished in the reconstructed Indo-European original language . In addition to an indicative for an objective statement (reports), she also knew the subjunctive with which the speaker expressed his will (expecting and wanting) or a subjectively not real concept (wishes and ability, enabling, imagining), the optative (wishes) that expressed a wish or a possibility, the imperative (commands), which one used to command, and the injective (prompting and mentioning) as an expression of a prohibition.

The Latin subjunctive

Historically, the subjunctive was one of the modes in Latin , the counterpart of the indicative. And how it is indicative of the three times the present tense , the past tense and the future tense are (with the relevant early forms Perfect , Past Perfect and Future Perfect ), for all these forms would also be expected, the corresponding subjunctive form.

The concept of the subjunctive comes from the late Latin modus coniūnctīvus , actually “a way of saying that serves to connect sentences”, from Latin coniungere “to connect”, “to bind together”.

In the Romance languages , some of the Latin forms have been lost. In Latin there are, in comparison, the formal equivalents to Spanish:

| Latin subjunctive | Spanish subjunctive | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Present subjunctive | cantes | Subjuntivo presente | cantes |

| Imperfect subjunctive | cantares | - | - |

| Subjunctive perfect | cantaveris | Futuro de subjuntivo | cantares |

| Subjunctive past perfect | cantavisses | Imperfecto de subjuntivo | cantaras or cantases |

The subjunctive of the two future forms is formed by the Latin in the Coniugatio periphrastica through the past participle with the corresponding form of the auxiliary verb esse . Or it replaces it: Instead of the subjunctive future I, the present subjunctive is chosen in relation to a main tense, the imperfect subjunctive in relation to a secondary tense, instead of the future II subjunctive in relation to a main tense the perfect subjunctive, in relation to a secondary tense Subjunctive past perfect.

The subjunctive is in Latin in main clauses as Iussiv than opt as Hortativ than Deliberative and as prohibitive used in conditional sentence structures than Irrealis and as a potentiality , and in subordinate clauses, which started with the conjunctions ut , cum , ne initiated and some other and in indirect questions .

In Latin , the subjunctive has a wide variety of functions. In addition to the volitive function of wishing and willing , the dubitative function is also expressed in order to point out the assessment of the validity, security or uncertainty of an action taking place. In the Latin language , from which the Romance languages are derived, the infinite verb, whose task it is to make a statement about a subject, only has three modes: the indicative, the subjunctive and the imperative. In Latin, however, the subjunctive does not have so much the meaning of an expression of a desired form (optative), but rather stands for an expectation of the future. The Latin subjunctive now combined several functions of the Indo-European subjunctive (expecting), the voluntative (wanting) and the optative (wanting and being able to, enabling, thinking) and the like. a. m. With the emergence of the Romance languages there was a renewed restructuring of the modes. You will now find four modes for the finite verbs: the indicative, the subjunctive, the imperative and the conditional. With a generous interpretation, the infinite forms, i.e. the participle, the infinitive and the gerund, could also be counted among the modes.

The functional aspect of the modes allows the speaker to adopt a certain (subjective) attitude towards the notion to be promised, his ultimately communicated sentence statement. For example, the speaker will use a form of mode to express whether he believes the content of the sentence or not, or the mode can express whether he wants something or not.

The restructuring of the modes from the "Indo-European language" and in particular with regard to the Latin subjunctive resulted in certain (partial) functions of the modes being combined and others newly formed in the Latin subjunctive. A part of the Indo-European subjunctive had the function of a future tense, another part function together with the optative formed a new subjunctive. In Latin, the Indo-European optative and the subjunctive have merged.

Altogether there are four different forms of the subjunctive in Latin, these are the "present subjunctive", "imperfect subjunctive", "perfect subjunctive" and "perfect subjunctive". In Spanish the number had doubled.

The German subjunctive and the Spanish subjunctive in comparison

Although often translated as subjunctive in literature , the subjunctive does not represent a direct equivalent to the German subjunctive. However, there are certain "linguistic relics" in the German language that are similar to the Spanish subjunctive: